4. Skills and processes in occupational therapy

Edward A.S. Duncan

Overview

This chapter focuses on theoretical foundations of what occupational therapists ‘do’. As the preceding chapter concluded, humans and the systems and environments in which they exist are complex processes. Describing occupational therapy, which focuses on individuals within the context of their physical and social environments, is not, therefore, quite as simple as it may at first appear. This chapter commences with a brief summary of occupational therapy definitions. Over the years, there has been considerable interest within occupational therapy literature regarding the nature of practice and the skills of an occupational therapist. In order to address this, the chapter will examine the various skills (core, shared and specialist) of an occupational therapist. The chapter then concludes by examining the occupational therapy process.

This chapter:

• highlights the core skills and processes of occupational therapy

• separates skills into those that are core, shared or specialist for practice

• outlines the occupational therapy process and its cyclical nature

• examines issues arising in assessment, goal-setting and evaluation.

Defining occupational therapy

Definitions are important. To define something is to clarify a topic and provide a vision of its function. Definitions also set boundaries and limitations. Therefore, definitions should be a useful tool in the description of occupational therapy. However, as previously acknowledged, defining occupational therapy can be complex. Despite or perhaps because of this, a multiplicity of occupational therapy definitions exist. The College of Occupational Therapists (COT) provides the following brief description of occupational therapy,

Occupational Therapy enables people to achieve health, well being and life satisfaction through participation in occupation. (College of Occupational Therapists 2004a)

The World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) describes occupational therapy as:

a health discipline which is concerned with people who are physically and/or mentally impaired, disabled and/or handicapped, either temporarily or permanently. The professional qualified occupational therapist involves the patients in activities designed to promote the restoration and maximum use of function with the aim of helping such people meet the demands of their working, social, personal and domestic environment, and to participate in life in its fullest sense. (World Federation of Occupational Therapists 2003)

This definition is significant, as it considers the role of the occupational therapist in relation to the environment, an area of increasing relevance in contemporary practice.

The WFOT (2003) provides a further 37 definitions of occupational therapy that have been developed by its national member associations. Reviewing comparative definitions of occupational therapy, it is apparent that there is substantial consensus of opinion regarding the definition of occupational therapy. National differences appear more reflective of the differing layers of complexity considered rather than significant differences of opinion.

Defining the skills of an occupational therapist

The skills of an occupational therapist are many and varied, and are often presented in seemingly simple ways. This is both the profession's strength and greatest challenge. A key skill of an occupational therapist is their ability to bring an occupational perspective, in terms of both a person's ability and their identity, to the therapeutic context. Within this context, occupational therapists work with client's strengths and address areas of occupational dysfunction. To achieve this, occupational therapists use a range of skills: core, shared (sometimes referred to as ‘generic’) and specialist.

Core skills in occupational therapy

The ‘core’ of an object is it most important part. From there everything else develops. (Schwartz 1994)

If an uninformed observer were to witness the work of occupational therapists from different specialties, their initial impression might be, at least on a superficial level, that they have little in common. Therapists working in social services, mental health and physical rehabiliation often appear, at first glance, to be doing different things. In all honesty, it must be admitted that at times they are — practice in some areas has lost its focus. This, however, is not how it should be.

Defining practice and developing a shared understanding of a profession's key competencies and processes are vital to its development. Mosey was perhaps the first theorist to tackle the concept of core skills in occupational therapy rigorously (Mosey 1986). Within the UK, the 1990s witnessed considerable interest and effort invested in further identifying and describing occupational therapy's core skills (Thorner, 1991, Renton, 1992, Hollis, 1993a, Hollis, 1993b, Hollis and Clark, 1993 and Phillips and Renton, 1995). The reason that such discussion was stimulated is reflective of the complexity of occupational therapy and the multi-layered components of each skill.

The COT outlined seven core skills (College of Occupational Therapists 2004a):

• collaboration with the client

• assessment

• enablement

• problem-solving

• using activity as a therapeutic tool

• group work

• environmental adaptation (Creek 2003).

Hagedorn recognized the complexity of occupational therapy and the difficulties that are faced when attempting to define the core skills of the profession, stating that:

Our core competencies and processes must somehow encompass the nebulous aspects of professional judgment and reasoning, problem solving and research as well as the ‘hands on’ forms of therapeutic knowledge and skill … This exercise will probably demonstrate that it is far from easy to untangle the things which are only done by occupational therapists from those which many other professions may do. (Hagedorn 2001, p.34)

Analysis and adaptation of occupations

The analysis of occupations and their use in therapy has also been recognized as a core skill of the occupational therapist (Hagedorn 2001). The analysis and prescription of occupations have two purposes:

• to deal with problems experienced by the client in all aspects of their everyday life — frequently classified as work, leisure and self-care

• the use of occupations as specific therapeutic interventions to address occupational perfomance difficulties and assist in the development of a positive occupational identity.

Activity analysis involves dissection of an occupational form into its component parts (tasks) and sequence, looking at its stable and situational components and evaluating its therapeutic potential. In doing so, it finds or adjusts an occupation for therapeutic benefit and enables a person to engage or re-engage in some form of occupation (Kielhofner & Forsyth 2009). Occupational therapists carry out activity analysis in order to consider:

• the kind(s) of performance needed to achieve the occupational form, e.g. cognitive, motor, physical, interpersonal (the headings used for detailed analysis will depend on the selected conceptual model or frame of reference)

• the degree of complexity of the activity

• the social or cultural associations

• defining the component tasks of which the occupational form is composed

• analysing the sequence of task performance and whether this is fixed or flexible

• defining the tools, furniture, materials and environment required for completion of the occupational form

• defining and taking account of safety precautions or risk factors.

Environmental analysis and adaptation

This is another skill used in a way that is core to occupational therapy practice. Occupational therapists recognize that the physical and social environments can have an important beneficial or detrimental effect on the individual. Environmental analysis may provide information on the causes of problems for the individual, explanations for behaviour or ideas or suggestions for therapeutic adaptation.

As conceptual models of practice have developed within occupational therapy, core skills have become increasingly linked to theory. Conceptual models can provide assessment(s) and taxonomies that assist in the detailed and structured analysis of occupations (see Kielhofner & Forsyth 2009 and Chapter 6 for an example of this). Frames of reference provide theoretical frameworks to support the therapeutic use of self (read Chapter 6, Chapter 7 and Chapter 8 for further information).

Shared skills

It is acknowledged that, as well as their core skills, each occupational therapist has a variety of shared skills. Whilst shared, these skills are no less essential to practice. Occupational therapists draw on the wealth of assessments and interventions that have not been developed by occupational therapists but facilitate the development of occupational performance and assist in the creation of a greater occupational self-identity.

The use of interventions that are not occupational therapy-specific is a contentious topic, as the profession becomes ever more deeply occupation-focused. Do non-occupational therapy-specific interventions have a place in the profession today? Several of the chapters in this book address this issue, either directly or indirectly.

Occupational therapists have a range of shared skills. Some of the most central are described below.

Leadership and management

Often placed together, leadership and management are two important but distinct skills.

Management

Occupational therapists have to manage services, a case load, an academic department or research team resources, and, importantly, themselves. The therapist needs to set standards, monitor quality and audit performance. These findings need to be communicated within the profession and to others. The therapist must be critically aware of their performance, seeking regular supervision and evaluating and updating personal knowledge. Management is not, therefore, a skill that is the remit of the head of a service, but the responsibility of all staff, albeit in differing ways. Furthermore, as well as managing others, therapists must also be able to manage themselves. Self-management consists of the actions and strategies we use to direct our own activity and ensure that we remain fit for purpose at work and at home. Bannigan (2009) describes the importance of self-management and the development of professional resilience in the face of the many challenges that arise in the workplace.

Leadership

Leadership is different from management. Whilst management has been defined as the ‘bottom line … how can I best accomplish things’, leadership has been defined as knowing ‘what are the things I want to accomplish’ (Covey 1989, p.101). Leaders in occupational therapy develop innovative approaches to intervention, work with clients in new ways, spot opportunities and develop services. The historical view of management and leadership as components of the same role is increasingly recognized as ineffectual. Indeed, the developing roles of consultant and clinical specialist occupational therapists (within the UK) appears to recognize that certain career pathways offer and require particular leadership qualities. Managing a service is an alternative professional pathway. Therefore, the leader of an occupational therapy team is not necessarily the manager, but may be a senior clinician with the vision and skills to move the service forward. Developing as a leader, however, is more than merely a professional skill; it is a personal and professional quality.

An awareness of one's need for continuous self-improvement and openness to others' perspectives of our own leadership qualities is essential. Whilst everyone will have their own leadership style, lots can be learned from other people. Often the best way to start devloping this quality is to observe leaders you admire (both within and outside the profession), taking a bird's-eye view of their practice/life. What do they do that makes you admire them? How do they deal with other people? How do they deal with themselves? What is their vision? How do they maintain their integrity in difficult situations? Conversly, the same exercise can be carried out with individuals whose practice you may not like to emulate! Reflect on these observations and consider any lessons that can be learnt. What would you wish to integrate into your practice/life?

As well as observation, a lot can be learnt from the wealth of literature that is available on this subject (e.g. Covey, 1989 and Goleman et al., 2002). Christiansen (2009) writes on leadership with direct reference to leadership in occupational therapy. Ultimately, however, leadership qualities are lived, developed and refined over a lifetime.

Therapeutic use of self

The therapeutic use of self is arguably one of the most important skills a therapist has. Mosey (1986) describes an occupational therapist's use of self as a concsious therapeutic tool and suggests that there is a difference between a spontaneous interaction that is unplanned and a planned interaction that, whilst appearing spontaneous, is guided and informed. Yarwood and Johnstone (2002) suggest four issues that essentially relate to the therapeutic use of self and the development of a therapeutic relationship:

• ‘Establish rapport;

• Respect the wishes of the client;

• Use honesty and strive to develop a collaborative approach; and

• Adapt to communicate effectively with all kinds of people' (p.327).

Occupational therapists have adopted various theoretical frameworks that assist in the development of the therapeutic use of self in differing ways. These include the client-centred, the cognitive behavioural and the psychodynamic frames of reference (see Chapter 11, Chapter 12 and Chapter 13 for further information).

Research

Research is a central component of occupational therapy practice (Ilott & White 2001) and the emphasis on research is arguably the single most significant development that has occurred in occupational therapy in the last 20 years (Duncan 2009). Every occupational therapist is required to use skills in research. This does not mean that every occupational therapist must carry out independent research, but at the very least everyone should be effective and critical consumers of research (Ilott & White 2001). The skills required to do this include:

• information and communication technology skills, to search and locate the literature

• critical appraisal skills, to evaluate research

• development of a personal evaluative perspective, to challenge custom and practice

• ability to integrate research into practice, in order to deliver consistently the highest quality of service available.

Specialist skills

Specialist skills are skills that cannot be expected of a competent clinician without further training, supervision and expertise (Duncan 1999). Occupational therapists can develop specialist skills that are either an extension of their core skills, such as specialist assessments (e.g. the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS); Fisher 1997), or an extension of their shared skills, such as undertaking advanced splinting or psychotherapy training (Duncan 1999).

Defining the occupational therapy process

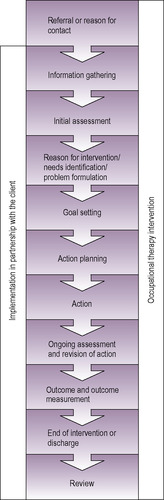

The occupational therapy process is the name given to the series of actions a therapist initiates in order to provide services to their client. This process is clearly not unique to occupational therapy. It is a form of problem analysis and solution that has been used by various healthcare professionals. There have been several representations of the process in occupational therapy, each differing a little from the others in accordance with each author's personal concept of the sequence. Generally, there is close agreement on the basic format. This involves gathering information concerning the client, their situation and challenges, carrying out assessments, identifying and formulating the problem or need, setting goals, setting consequent priorities for action, deciding on how to achieve these, implementing action and evaluating the outcome. Creek (2003) illustrates this process in a linear model (Fig. 4.1). Hagedorn (2001) uses similar points but illustrates the process's cyclical nature (Fig. 4.2). In practice, the occupational therapy process is often not linear (Creek 2003) or even cyclical. Frequently, these activities occur in synchrony and are repeated at various stages of therapy. The process is therefore circuitous, with overlapping and interwoven aspects of the process occurring throughout.

|

| Fig. 4.1 • The occupational therapy process viewed linearly. Reproduced by permission of the College of Occupational Therapists from Creek 2003. |

|

| Fig. 4.2 • The occupational therapy process viewed cyclically. |

As shown in Figure 4.2, a referral is received by the therapist. This starts the intervention sequence. The therapist will then enter the cycle of information-gathering and problem analysis, decision-making, implementation of action and review of outcome, which is repeated until intervention is judged to be completed.

Throughout this process, the occupational therapist employs the unique combination of knowledge, skills and values that form the practice of occupational therapy. The way in which this happens is often informed and directed by conceptual models of practice and frames of reference, several of which are outlined in Chapter 6, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, Chapter 9, Chapter 10, Chapter 11, Chapter 12, Chapter 13 and Chapter 14.

Assessment

Why assess?

Assessment is the gathering of relevant information that informs the prioritization and development of clinical goals for intervention. Assessments also assist in measuring change during interventions and evaluation of interventions at their conclusion. All assessment procedures require a basis of theoretical knowledge and practical experience and expertise. There are several basic skills required to carry out effective assessments:

• clinical judgement of what is to be assessed

• decision-making regarding the most appropriate assessment methods to use

• objectivity

• good observation skills

• production of consistent, accurate and, where possible, replicable results

• communicating results clearly to others

• client sensitivity.

Assessment should be recognized as a means to an end — identification of the problem; definition of a starting point for intervention; measurement of progress; evaluation of outcome. As well as assessing an individual's ability, it is also important to assess the context in which they are carrying out the task — the environment.

Environmental assessment

The way in which an environmental analysis is carried out depends on both the needs of the client and the conceptual model/frame of reference within which the therapist is working, as these will alter the significance of the components that are observed.

In general terms, the occupational therapist will observe and accurately record the physical environment (e.g. buildings, interiors, heat, light, sound) and the social environment (e.g. How many people are in the environment? What is the nature of the relationships? How supportive are they? and so on) that contribute to or detract from a client's performance and positive occupational identity.

How do you assess?

Assessments can be carried out in either a structured or an unstructured manner; depending on their aim, both can be valid (Kielhofner & Forsyth 2008). Using either structured or unstructured procedures, assessment information can be gathered through a variety of methods:

• observation — e.g. of a client performing an occupational form

• interview — e.g. with the client or relevant others

• self-report or checklists — e.g. to provide a client perspective

• performance tests — e.g. of physical or cognitive ability

• measurement techniques — e.g. of physical performance.

In practice, a combination of these methods is often used; observation may be combined with interview, a structured assessment with an unstructured assessment. Therapists may interview a client, watch them carry out a task or occupational form, and ask them to complete a checklist or self-report instrument. Frequently, some of these assessments will be unstructured. Recently, a structured approach to multiple data-gathering has developed. The Model of Human Occupation (see Chapter 6) has developed some structured assessments that utilize a combined method of assessment. This is an innovative approach to structured assessment, as the use of mutiple methods causes statistical challenges in developing the reliability of the assessment. These assessments represent a useful addition to the reportoire of available assessments.

Unstructured assessment

Unstructured assessments are also referred to as informal, ad hoc or unstandardized. Many unstructured assessments are constructed by occupational therapists who may have developed them to meet local needs. Whilst unstructured assessments can never provide the reliability of structured assessments, several reasons exist that can justify their use:

• lack of an appropriate structured assessment

• lack of acceptability of structured assessments to a client

• use of unstructured assessments to add to information previously gained through structured assessment

• lack of time to complete a structured assessment

• structured assessments not available at an unforeseen opportunity to gather more information (Kielhofner & Forsyth 2008).

Structured assessment

Structured or standardized assessments have been rigorously developed over a period of time and are designed to be dependable. Two specific issues are of particular importance in the development and appraisal of a structured assessment: validity and reliability.

Validity

Validity concerns whether the assessment actually deals with matters that are appropriate to the situation and measures the right things. There are various different forms of validity (Oppenheim 1992):

• Face validity. Does the assessment look as if it does the things it is supposed to?

• Concurrent validity. Does the assessment gather relevant and associated information?

• Predictive validity. Can reliable conclusions be drawn from the assessment's findings?

Depending on the focus of the assessment, a structured assessment may require more than one form of validity to be evaluated in its development and appraisal. Furthermore, an assessment's validity grows with each study that develops its evidence base.

Reliability

Reliability means that you can be sure that, each time the test is used, the findings can be depended upon. Fundamentally, there are two forms of reliability:

• Test–retest reliability. The assessment is repeated and the same findings result.

• Inter-rater reliability. The assessment is repeated by different therapists, with the same result.

There are numerous structured assessments on the market. Several of them are discussed in this text. Whilst many structured assessments can be used by all qualified occupational therapists, there are some that require specific further training (e.g. AMPS; Fisher 1997).

Goal-setting

Having assessed the client and formed a professional perspective of a person's priorities and needs, it is important to set collaborative goals for intervention. ‘Goals are targets that the client hopes to reach through involvement in occupational therapy’ (Creek 2002, p.129). Developing goals is a vital component of the occupational therapy process. However, as Wade (2009) clearly states, ‘setting goals with patients and monitoring their achievement is a core practice within much of rehabilitation, but the evidence base behind this practice is patchy’ (Wade 2009, p.291). Despite such a lack of evidence, and in anticipation of greater clarity regarding its effectiveness as an intervention, goal-setting is likely to remain a central feature of practice. Park (2009) provides a good overview of the goal-setting process in occupational therapy. Without goals, neither client nor therapist can have any idea of when to finish their intervention or develop new goals. This, however, does not mean that goals cannot be amended during the therapeutic process. It may be that the initial goals were either too easy or too ambitious and a reappraisal is required.

Developing goals

Fundamentally, two types of goal exist:

• Long-term goals. These are the major goals, the final destination where both client and therapist view therapy as having been successful. Long-term goals are also referred to within the literature as ‘aims’ (Foster 2002).

• Short-term goals. These are the more immediate goals of therapy, the stepping stones to achieving the longer-term goal or aim. Short-term goals often form the component parts of a longer-term goal (e.g. making a cup of tea may be a short-term goal leading to independent meal preparation). In order to maintain motivation and build upon skill development, short-term goals are often developed in a hierarchical structure (Creek 2002).

Creek (2002) also refers to the development of intermediate goals, defined as ‘clusters of skills to be developed or barriers to be overcome on the way to achieving the main goals of therapy’ (p.122). Creek's (2002) rationale for intermediate goals is that the long-term goal may appear too distant or challenging, and the setting of intermediate goals provides a more realistic or achievable option.

Agreeing goals

Involvement of clients in the decision-making process surrounding setting goals is crucial. Neistadt (1995) found that clients who participated in the development of their goals made statistically and clinically significant gains in their performance ability.

Whilst structured methods for developing goals exist (Ottenbacher & Cusick 1990), the majority of therapists develop their own goals without using such procedures. It has, however, been suggested that such decision support aids are a useful component of therapy (Barclay 2002). The advantages of decision support aids in the development of short- and long-term goals constitute an area that deserves further research and evaluation.

Regardless of whether a structured method of setting goals is used or not, goals should be measurable and clear to all parties. An example of an unclear goal would be ‘eat more healthily’, whilst a clearer and more measurable goal might read ‘be able to prepare and cook four separate meals using at least five different vegetables and including either chicken or fish’.

Interventions

Therapy, treatment and intervention are largely synonymous terms; however, each suggests certain philosophical beliefs about the position and role of the client in relation to the therapist. For example, the term ‘treatment’ suggests a largely passive experience where a person is done to instead of done with. The term ‘intervention’ is preferred in this text, as it recognizes the intrusion (however welcome) in a person's life and indicates a broadly based form of service provision. In one of the UK's earliest theoretical texts on occupational therapy, it was suggested that the range of occupational forms that could be used for therapeutic intentions was infinite. Of greater importance was the aim of their use and whether this was suitable and achievable (MacDonald 1960). This perspective remains as true today as it did then.

Application of occupational forms as therapy

The selection of an occupational form as a therapeutic intervention requires that a balance be achieved between the needs and interests of the client, the personal repertoire of skills possessed by the therapist, and the requirements of the conceptual model or frame of reference within which the therapist chooses to work. Occupational forms should be specifically selected for the individual client in respect of the developed goals.

Occupational forms may be used casually for recreation or as pastimes; such use is perfectly valid in the right context; however, their use in this way is diversional occupation, not occupational therapy.

Adapting occupational forms

The occupational form may be presented in an unadapted manner or may be adapted to meet the specified goals. Types of adaptation that may be required to assist the client to achieve their goals include:

• environmental, e.g. location, setting, milieu

• equipment, e.g. quantity of tools/materials, adaptation to tools

• social, e.g. number of people, degree of interaction

• physical, e.g. position, strength, range of movement

• cognitive, e.g. complexity, sequence, need for instructions

• emotional, e.g. interest, meaning, self-expression

• temporal, e.g. duration, repetition

• structural, e.g. order of tasks, omission of non-essential tasks.

The amended factors of an occupational form can then be graded over time to increase the client's occupational performance and development of a positive occupational identity.

Environmental context of interventions

Interventions can occur in a client's natural environment (such as their home or community), in proximate environments (such as a group home/hostel or a local community near their current residency) or in artificial environments (such as hospitals or prisons). Within these settings, interventions may take place in various forms of group setting (whether naturally occuring groups such as a football team, or artificial groups such as an on-ward cooking group) or individually.

Environmental adaptation

The therapist may suggest adapting, removing or adding to elements of the physical environment — e.g. physical features of buildings, access, sound, colour, lighting level, temperature, decor, furniture, information content — in order to remove obstacles to performance or to enhance the opportunities for performance, learning or development. Occupational therapists should also consider adapting the social environment (i.e. the groups of people that a person is involved with in their environment), as these can also postively or negatively affect the client in achieving their goals.

Specific interventions are shaped and influenced by the frames of reference and conceptual models of practice that guide them. Interventions from each of these theoretical constructs are described in detail in the following chapters.

Evaluation

Evaluating the effectiveness of occupational therapy is an ethical and professional imperative.

Individual evaluation

Evaluation is the method by which the client, therapist and other relevant individuals (such as carers) or bodies (such as the multidisciplinary team) know if the agreed goals have been met. Whilst evaluation is an ongoing process throughout therapy, it is the final evaluation that is often most significant. Measuring ‘success’ is often achieved using the same assessment measures employed at the initial and on-going assessment and looking for significant changes in the desired direction. Evaluation can also be measured by examining whether the specified goals have been met and by discussing the client's perspective of the situation.

Service evaluation

As well as evaluating individual client's interventions, occupational therapists can and should periodically evaluate their service as a whole. Several mechanisms can be used to assist in this process.

Reviewing existing service strategy

The service strategy (or a document with a similar title and aim) outlines an occupational therapy service's aims, guiding philosophy and objectives. This is an important document, which can be appropriately adapted to communicate the workings of an occupational therapy service to clients, carers, new members of staff, other members of staff not engaged in occupational therapy, students and the public. Service strategies should include:

• an executive summary

• historical background to the service

• current strategic drivers (e.g. relevant national, professional and local policies)

• the vision for the service (aim, philosophy of care, clinical perspective/conceptual model of practice used etc.)

• specific objectives against which the service can be measured.

Audit service against existing standards

These may be clinical standards set by national organizations (e.g. the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) or Quality Improvement Scotland (QIS)) or standards set by professional bodies such as COT (College of Occupational Therapists 2004b) or AOTA (American Occupational Therapy Association 2005).

Gaining feedback from clients who have used the service

This could be achieved through either questionnaire or interview procedures.

Gaining feedback from colleagues

This can also be achieved through either questionnaire or interview procedures.

Summary

This chapter has explored the theoretical foundations of what occupational therapists ‘do’. Differing definitions of occupational therapy were presented and referred to. It is recognized that each definition holds a commonly shared vision of the profession.

Occupational therapy's apparent simplicity is both its strength and its greatest challenge. This chapter's brief review of an occupational therapist's skills and the component parts of the occupational therapy process illustrates that, whilst occupational therapy interventions are not always complex in the technical sense of the word (Duncan et al 2007), they can certainly be multi-factorial and challenging to describe. Perhaps it is for this reason that the challenging nature of delivering sophisticated occupational therapy interventions is not always immediately apparent to those who observe them but do not appreciate the process at work.

• What do you consider to be the key skills you use in practice? How aware of them are you when you use them?

• How do you choose which method of assessment to use with each client?

• Have you seen or do you use goal-setting in practice? What are its strengths and limitations?

• How do you evaluate your practice?

References

American Occupational Therapy Association, Standards of Practice for Occupational Therapy. (2005) ;http://www.aota.org/general/otsp.asp; (accessed 25.01.05).

Bannigan, K., Management of self, In: (Editor: Duncan, E.A.S.) Skills for Practice in Occupational Therapy (2009) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 231–248.

Barclay, L., Exploring the factors that influence the goal setting process for occupational therapy intervention with an individual with spinal cord injury, Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy 49 (2002) 3–13.

Christiansen, C., Leadership skills, In: (Editor: Duncan, E.A.S.) Skills for Practice in Occupational Therapy (2009) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 313–322.

College of Occupational Therapists, Definitions and Core Skills for Occupational Therapy. (2004) College of Occupational Therapists, London.

College of Occupational Therapists, Professional Standards for Occupational Therapy Practice. (2004) College of Occupational Therapists, London.

Covey, S., The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. (1989) Simon & Schuster, London.

Creek, J., Treatment planning and implementation, In: (Editor: Creek, J.) Occupational Therapy in Mental Healththird ed (2002) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 119–138.

Creek, J., Occupational Therapy Defined as a Complex Intervention. (2003) College of Occupational Therapists, London.

Duncan, E.A.S., Occupational therapy in mental health: it is time to recognise that it has come of age, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 62 (11) (1999) 521–522.

Duncan, E.A.S., Developing research in practice, In: (Editor: Duncan, E.A.S.) Skills for Practice in Occupational Therapy (2009) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 279–292.

Duncan, E.A.S.; Paley, J.; Eva, G., Complex interventions and complex systems in occupational therapy, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 70 (5) (2007) 199–206.

Fisher, A., Assessment of Motor and Process Skills. (1997) Three Star, Fort Collins.

Foster, M., Skills for practice, In: (Editors: Turner, A.; Foster, M.; Johnson, E.S.) Occupational Therapy and Physical Dysfunction: Principles, Skills and Practice (2002) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 85–105.

Goleman, D.; Boyatzis, R.E.; McKee, A., Primal Leadership: Realizing the Power of Emotional Intelligence. (2002) Harvard Business School, Harvard.

Hagedorn, R., Foundations for Practice in Occupational Therapy. (2001) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Hollis, V., Core skills and competencies: what is experience? Part 1, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 56 (2) (1993) 48–50.

Hollis, V., Core skills and competencies: application and expectation, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 56 (5) (1993) 181–184.

Hollis, V.; Clark, C.R., Core skills and competencies: the competency conundrum. Part 2, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 56 (3) (1993) 102–106.

Ilott, I.; White, E., College of Occupational Therapists research and development strategic vision and action plan, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 64 (6) (2001) 270–277.

Kielhofner, G.; Forsyth, K., Assessment: choosing and using structured and unstructured means of gathering information, In: (Editor: Kielhofner, G.) Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Applicationfourth ed (2008) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, pp. 155–170.

Kielhofner, G.; Forsyth, K., Activity analysis, In: (Editor: Duncan, E.A.S.) Skills for Practice in Occupational Therapy (2009) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 91–104.

MacDonald, E.M., Occupational Therapy in Rehabilitation. (1960) Baillière, Tindall & Cox, London.

Mosey, A.C., Psychosocial Components of Occupational Therapy. (1986) Raven, New York.

Neistadt, M.E., Methods of assessing clients’ priorities: a survey of adult physical dysfunction settings, American Journal of Occupational Therapy 49 (1995) 428–436.

Oppenheim, A.N., Questionnaire Design. Interviewing and Attitude Measurement. (1992) Continuum, London.

Ottenbacher, K.J.; Cusick, A., Goal attainment scaling as a method of service evaluation, American Journal of Occupational Therapy 44 (1990) 519–525.

Park, S., Goal Setting in Occupational Therapy: a client centred perspective, In: (Editor: Duncan, E.) Skills for Practice in Occupational Therapy (2009), pp. 105–122.

Phillips, N.; Renton, L., Is assessment of function the core of occupational therapy?British Journal of Occupational Therapy 58 (2) (1995) 72–74.

Renton, L.B.M., Occupational therapy core skills in mental handicap: a review of the literature, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 55 (11) (1992) 424–428.

Schwartz, C., Chambers Dictionary. (1994) Chambers, Edinburgh.

Thorner, S., The essential skills of an occupational therapist, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 54 (6) (1991) 222–223.

Wade, D., Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how, Clinical Rehabilitation 23 (2009) 291–295.

World Federation of Occupational Therapists, Definitions of Occupational Therapy. (2003) ;http://www.wfot.org.au/Document_Centre/default.cfm; (accessed 25.01.05).

Yarwood, L.; Johnstone, V., Acute psychiatry, In: (Editor: Creek, J.) Occupational Therapy and Mental Healththird ed (2002) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 317–333.