8. The Person–Environment–Occupational Performance (PEOP) Model

Charles Christiansen, Carolyn M. Baum and Julie Bass

Overview

This chapter summarizes the history and evolution of the Person–Environment–Occupational Performance (PEOP) Model, a model for practice first conceived during the 1980s in the USA. As a guide to occupational therapy intervention, the PEOP Model can be considered a transactive systems model. The model focuses on the client and on relevant intrinsic and extrinsic influences on the performance of everyday occupations. It can be applied to individuals, groups (or organizations) and populations. The PEOP Model has characteristics that are similar to other social ecological models, in that it identifies three relevant domains of knowledge for occupational therapy practice:

• the person (intrinsic factors)

• the person's situation or context, including the relevant physical and social environment (extrinsic factors)

• the occupations of importance to the client's well-being (activities, tasks and roles).

It is transactive in that it views everyday occupations as being affected by, and affecting, the client and the client's context. It is client-centred in that it values and requires the active involvement of the client in determining intervention goals. It is different from other models because it makes the intrinsic, extrinsic and occupational factors explicit and applies them at the person, organizational and population levels.

The PEOP Model:

• is client-centred

• applies to individuals, groups and populations

• is intended to be top-down, focusing first on the situations of clients

• allows the practitioner to organize current knowledge of the intrinsic and extrinsic factors in their interventions

• uses a systems perspective

• serves as a guide to creating a complete occupational profile of the client

• values collaboration with the client, with important others within the client's social circle, and other professionals concerned about the client's well-being

• works to achieve a match between the client's goals and the goals of occupational therapy intervention

• believes that outcomes must be related to well-being and quality of life

• incorporates the three components of evidence-based practice: the best evidence from research, professional and clinical expertise, and the client's unique values and circumstances.

Introduction: origins and aim of the PEOP Model

In 1985 work began in the mountains of Colorado on what was to become the PEOP Model. At the time, there was a growing awareness that it was necessary to organize the knowledge that was being used by occupational therapists in a manner that would identify, clarify and emphasize the unique contribution of occupational therapy to the health and well-being of individuals, groups and populations. We knew that occupational therapy could provide practical and relevant interventions that enabled people to preserve or improve the quality of their lives. Yet, at that time, the most influential textbooks in the field were continuing to organize their content using a biomedical approach that resembled the diagnosis and pathology-focused approach of allopathic medicine. Influenced by writers from medicine who were calling for more health-oriented approaches (e.g. Engel 1977), as well as writers from occupational therapy who openly lamented the field's apparent divergence from ideas central to its founding (e.g. Shannon, 1977), we set about reframing the organizing structure for knowledge relevant to occupational therapy theory and practice. We intended to propose a model that would provide practitioners with an intuitive and organized way to understand the areas relevant to supporting people's ability to perform or do the activities, tasks and roles necessary for everyday living. Through creating such a framework, we aimed to facilitate thinking in ways that would guide assessment, planning and the delivery of interventions. Our goal was to have a model that would be relevant, regardless of the settings in which occupational therapists worked, the types of client they served, or the ages, life stages or diagnoses of those clients. We also felt that creating such a model would encourage a more balanced approach to care that would encourage therapists to plan intervention with a focus on the life situations of their clients. This focus, we surmised, would require that therapists consider the person-related and environment-related resources and barriers relevant to a full understanding of how to enable their clients to perform or accomplish the particular occupations necessary to live satisfying lives.

The PEOP Model is now in its third generation (Christiansen and Baum, 1991, Christiansen and Baum, 1997 and Baum and Christiansen, 2005) and continously being updated. During the years since its inception, the knowledge generated from occupational science, neuroscience, environmental science and other biological and social sciences has enabled us to refine and extend our original ideas and to provide a more solid scientific basis for the constructs we believe are central to understanding the occupational performance of humans. Throughout this process of elaboration, we have been influenced by many emerging ideas and innovations in healthcare, disability, social policy, technology, rehabilitation and public health. Although some terminology has changed, definitions have been revised, and new concepts have been added, the basic philosophical orientation of the model and its central features have remained consistent. This, we believe, indicates that we were successful in achieving a model that was not only conceptually sound, but straightforward in its ability to organize a knowledge base of information useful for practice.

The PEOP Model values collaboration

Because occupational therapy is based on a cooperative approach toward care (Meyer 1922), the PEOP Model was designed to facilitate the development of a collaborative intervention plan with the client and with other professionals. Use of the term ‘client’ is meant to apply, whether the intervention is directly with a patient, a well community-dwelling child or adult, or a family, or done in consultation with a physician, a social worker, a student, an architect, an employee, an organization or an entire community. Each of these ‘clients’ would seek the knowledge and skills of the occupational therapist to address issues that influence occupational performance or the ability of people to participate fully in their lives. Occupational therapists provide a unique knowledge and skill set that bridges the world of the client and the world of healthcare and includes other important social services in communities. A core assumption is that people cannot truly be well if they cannot participate fully in their lives.

Occupational performance

The concept of occupational performance has become the mainstay of the development of most models of occupational therapy. Occupational performance operates as a means of connecting the individual to roles and to the sociocultural environment (Reed & Sanderson 1999, p.93). We define occupational performance as the complex interactions between the person and the environments in which they carry out activities, tasks and roles that are meaningful or required of them (Baum & Christiansen 2005).

A systems perspective

The PEOP Model is a systems model, recognizing that the interaction of the person, environment and occupational performance elements is dynamic and reciprocal, and that the client must be central to the care-planning or intervention process. Only the client (whether person, family, organization or community) is able to determine what outcomes are most important and necessary.

Client-centred

In the traditional medical model it is the practitioner who determines the approach to care. The PEOP Model provides a bridge from the biomedical model to a sociocultural model and provides students and clinicians with a tool to organize evidence for use in practice. That is, it recognizes impairments when they limit performance participation but also views the client in context, including a consideration of the abilities and strengths that a client can use to enable performance, as well the environmental characteristics that provide support, whether those include places, people, policies or technologies. Ultimately, the comprehensive assessment of a client, what that client needs and wants to do, and the environment clients will inhabit collectively determine the interventions aimed at enabling the client to perform valued roles, activities and tasks that are central to living, whether these pertain to management of self and others, work or community engagement. A central theme of the PEOP Model is that, ultimately, the client determines the performance goals toward which therapy is targeted.

The PEOP Model is used as a guide to creating a complete occupational profile of the client, which includes information about the client's perception of the current situation, and includes consideration of the client's roles, interests, responsibilities and/or mission and values. The assessment and planning phase of care is grounded in evidence. We believe that clients should enter into the intervention phase with a clear understanding of the outcome that should ultimately result. Intervention must be a collaborative endeavour, with effort and commitment contributed through the partnership of the practitioner and the client.

Description of the model

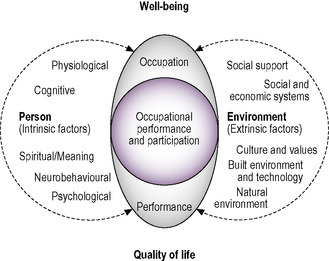

Figure 8.1 provides a graphic representation of the model. This representation is intended to convey that occupational performance is determined not only by the nature of the activity, task or role to be performed, but also by the characteristics of the person or client (depicted as intrinsic factors) and the environment (depicted as extrinsic factors). Performance and participation always occur in context, and ultimately determine well-being and quality of life. It should be noted that, for a given situation or context, the applicability or importance of given intrinsic and extrinsic factors will vary. The model presupposes that a complete assessment to plan intervention will include a consideration of each of the factors.

|

| Fig. 8.1 • The Person–Environment–Occupational Performance Model. Reprinted with permission from SLACK Incorporated. Christiansen, C.H., Baum, C.M., Bass, J., 2005. Occupational Therapy: Performance, Participation and Well-being, third ed. Slack Inc. Thorofare, NJ. |

Using the PEOP Model to plan care

The PEOP Model visually represents the constructs that must come together to support both the practitioner and the client in developing a realistic and sequenced plan of care. Success in this process depends on the practitioner's skills in forming a relationship with the client, asking the right questions, and being able to access the knowledge necessary to understanding the issues and options presented by the client's occupational performance issues and goals. Using the PEOP Model involves a ‘top-down approach’, in that it first considers the individual in context, identifying the client's roles, occupations and goals. The model requires the occupational therapist to use this context to address the personal performance capabilities/constraints and the environmental performance enablers/barriers that are central to the occupational performance of the individual.

Intrinsic factors

Intrinsic factors in the PEOP Model that are central to occupational performance are:

• physiological, including strength, endurance, flexibility, inactivity, stress, sleep, nutrition and health

• cognitive, including organization, reasoning, attention, awareness, executive function and memory, all necessary for task performance

• neurobehavioural, including somatosensory, olfactory, gustatory, visual, auditory, proprioceptive and tactile, as well as motor control, motor planning (praxis) and postural control

• psychological and emotional, including emotional state (affect), self-concept, self-esteem and sense of identity, self-efficacy and theory of mind (social awareness)

• spiritual: that which brings meaning.

Extrinsic factors

Extrinsic factors in the PEOP Model that are central to occupational performance are:

• social support, practical or instrumental support and informational support

• societal, including interpersonal relationships (groups), social and economic systems and their receptivity (policies and practices) to supporting participation, laws

• cultural, including values, beliefs, customs, use of time

• the built environment, including physical properties, tools, assistive technology, design and the natural environment, covering geography, terrain, climate and air quality.

Situational analysis

In order to incorporate key elements of planning, the occupational therapist completes a situational analysis. This analysis seeks information from the client by interview and by employing assessments that give the practitioner a clear understanding of constraints and/or barriers that may limit the person's activity and participation. As well, the practitioner will gain insight into barriers and environmental enablers that will limit or support the individual in doing the things he or she wants and needs to do.

There are a number of key elements of a plan of care in the PEOP Model. These client-centred elements change, depending on whether the client is a person, an organization, or the community, as reflected in a population approach. Each will be discussed.

The following situational analyses were designed to help the practitioner organize information to address the issues of individuals, of organizations and of communities. In each situational analysis, evidence underpins the practitioner's decisions as to what measures to include and which interventions to employ. All professionals are held to a standard — the expectation of competent practice using methods that have been objectively shown to be effective. Evidence thus becomes the filter through which clinical decisions about the type of evaluation or assessment and the interventions that will support the client in achieving their goals will be made.

Planning person-centred interventions

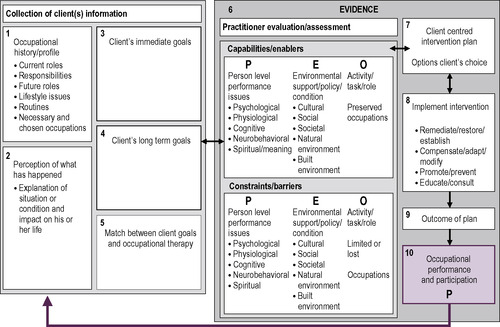

The following elements describe the steps necessary for gathering and analysing client-related information (Fig. 8.2).

|

| Fig 8.2 • A situational analysis: using the PEOP Model for planning person-centred interventions. Carolyn Baum, Julie Bass & Charles Christiansen. Used with permission. |

The collection of client information

The occupational history

It is during the process of obtaining a history that the practitioner learns what the person has done previously and how culture impacts on their everyday life. An occupational history should include a description of leisure interests and social activities, and provide a clear understanding of the responsibilities clients have for work and for self- and home management tasks.

Client's perception of the current situation

Another key element is the client's perception of the current situation. People (and groups) vary in the level of knowledge or understanding they have of their medical or health conditions. Thus, it is important to know what the client thinks has happened, how the situation is appraised, and what the client knows about a likely course of intervention. It is also important to estimate the impact that the current situation is having on a client's life experience(s).

The client's immediate and long-term goals

What are the client's goals? It is important to determine the client's long-term goals so that, as discussions emerge about short-terms goals, the practitioner can help the client plan the necessary goal-related steps. It is always easier to establish goals if the therapist has completed an occupational history. By knowing about the client's interests, skills, values, roles, traditions, habits and routines, it is possible to help formulate goals that not only will be achievable, but also will be meaningful. Current practice encourages therapists to avoid applying cultural stereotypes and to focus on the particular narrative of a given client.

Match between the client's goals and occupational therapy

The final step in the client information section of the analysis is to determine the match between the person's goals and the occupational therapy approach. If there is no match, the occupational therapist should make an appropriate referral to another professional or to other resources to address the client's goals. When there is a match, the practitioner should begin the second section of the situational analysis to determine the person's capabilities and enablers, and to identify barriers and constraints that will need to be overcome.

The evaluation and assessment of intrinsic (person) and extrinsic (environmental) factors that will impact on or support occupational performance

Selection of measures/assessments to understand the intrinsic and extrinsic factors

The person factors (intrinsic) include physiological, psychological, cognitive, neurobehavioural and spiritual characteristics. The environmental (extrinsic) factors include cultural, social and economic, natural environment, built environment, and social and societal influences on performance. Assessments are chosen that will allow the therapist to understand the person's capabilities and what might be limiting the individual's performance of activities, tasks or occupations that are central to fulfilling valued roles or expectations.

Client-centred intervention plan

With the client's information and the practitioner's assessment of the client's capacity and constraints, a client-centred plan is constructed. The practitioner uses their skill to help the client understand what is possible, and also helps the client understand the issues involved in helping to achieve identified goals. The client has the right and the practitioner has the responsibility to review and share available evidence that a given intervention will be able to help the client achieve their goals in the most effective and efficient manner. Identifying and communicating the evidence used to formulate a given intervention plan not only promotes sound reasoning, it also reflects the highest principles of ethical practice.

Implement intervention

Several interventions can and should be employed to meet the client's goals. These interventions range from remediation strategies designed to restore function to compensation, including promoting health, preventing secondary problems, and educating the client and their support network to be able to self-manage the situation. One additional intervention is advocating for change to remove societal barriers that limit occupational performance. These interventions are discussed throughout the interventions section of the book.

Outcome of the plan

Following the implementation of the plan, the client (hopefully) will be able to achieve their goals. Outcomes should be measured, not only to demonstrate the progress to the client, but also to demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of the occupational therapy interventions to the referral source, to other appropriate stakeholders and to the public. The effectiveness of occupational therapy must be public in order to shape the policies of institutions and payment sources.

Occupational performance and participation

The entire process leads to achieving the goals identified by the client and helping the client return to the level of everyday life that enables performance of roles, responsibilities and interests. Since many individuals have a chronic condition or a disability that requires a self-management strategy, part of the outcome should include the possibility of additional services from an occupational therapist, if an occupational performance issue emerges that would benefit from or require occupational therapy expertise.

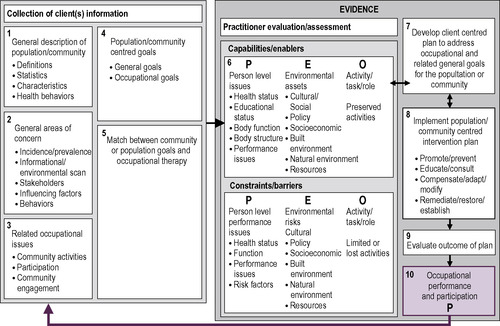

Addressing the occupational performance issues of communities/populations

The process described above fits well when the occupational therapist is working with individuals or small groups of people such as families. However, an emerging area of practice for occupational therapy addresses the occupational issues of communities and populations (Fig. 8.3). Population-based care may theoretically range from as large as all of the people in the world who fit some characteristic (e.g. people with AIDS, children who are homeless) or may reflect a small group of people or a community with issues of concern (e.g. mid-life women with family issues that affect their work for a company, or older people who have become isolated in a neighbourhood because of transport issues). Sometimes, these issues are identified within a more obvious or defined organizational structure, such as within a community group, business, or a group of people within a designated government category (e.g. people over 65 within a designated political or geographic jurisdiction). One might guess that the situational analyses conducted will look different in these different situations. Population-/community-centred situational analyses may serve as the starting point for occupational therapists who are interested in improving the health of populations or communities in general or working within specific organizations.

|

| Fig 8.3 • A situational analysis: using the PEOP Model for planning population- or community-centred interventions. Carolyn Baum, Julie Bass and Charles Christiansen, 2005. Used with permission. |

Consider a hypothetical situation where an occupational therapist who has worked with older people in long-term care settings for several years wants to continue to work with older people but would like to work with well elders to enable them to remain at home and improve their quality of life. How does the therapist begin? Does one already have the background and knowledge that will enable success in this new practice arena? Is one ready to begin immediately to promote these services to organizations that work with this population or in these communities? Such a possibility may occur, but is it likely?

In this situation, a population/community situational analysis may better prepare the therapist to understand the general characteristics and issues of the older population, the community in which clients live, and, most importantly, to plan interventions that will meet the needs and goals of specific organizations.

This example can be followed through a situational analysis. Although the therapist has worked with elders who have health conditions and diminished abilities in the long-term care setting, they do not have a clear understanding of well elders. So the therapist begins a population-/community-centred situational analysis by acquiring general information and conducting a broad assessment. What things should the therapist examine?

The collection of client information

General description of the population/community

This will help the therapist define the population/community (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity, income, education, employment, religion, geographic area), obtain statistics of interest (e.g. risk factors), and identify characteristics that are associated with people who are part of this population/community (e.g. knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, habits, preferences, sensitivities). This exercise may also support some of the therapist's assumptions and/or dispel any myths that may be commonly believed.

Identification of general areas of concern

For a given population/community, this requires the therapist to look outside of occupational therapy to gain a broader understanding of the pertinent array of critical issues (e.g. barriers, policy, supports, services, motivators for change). The therapist will often find these areas identified by local, national and international agencies and organizations, census information, and even reports from the popular press. In a sense the therapist is conducting an environmental/informational scan to learn more about the prioritized areas of concern for a population/community, the incidence/prevalence of the issues, and the major stakeholders (e.g. transport has been identified as a major issue for older people living in communities).

Related occupational issues

It is important to identify an occupational therapy role for this population/community. Some groups may not have significant occupational issues associated with them; however, others will. This step may require the therapist to explore occupational therapy literature that can help identify potential occupational performance-related issues. It is more likely, however, that such identification will result from using strong critical thinking skills coupled with the therapist's knowledge of factors that support (or limit) occupational performance (e.g. transport issues may limit engagement in all occupations that are typically done outside the home — shopping, financial matters, socialization and so on).

The population/community — general goals

It is important to identify areas of concern; these often come from the same sources, as noted two sections above. These goals may be broken into immediate goals and long-term goals, or they may be overall general objectives. Knowledge of these goals will help the practitioner in communications with stakeholders for this population/community. The population/community's occupational goals are developed from one's consideration of this and the previous two sections, and identification of how the general health of the community is understood by the stakeholders.

Match between the community or population goals and occupational therapy

The final step in the client information section of the analysis is to determine the match between the community or population goals and the occupational therapy approach. If there is no match, the occupational therapist should make an appropriate referral to another professional or to other appropriate resources qualified to address the client's goals. When a match is identified, the practitioner should begin the second section of the situational analysis to determine the community or popuation's capabilities and enablers, and to identify barriers and constraints that will need to be overcome.

The evaluation and assessment of intrinsic (person) and extrinsic (environmental) factors that will impact on or support occupational performance

Selection of measures/assessments/methodologies to understand the intrinsic and extrinsic factors

The occupational therapist selects appropriate tools to understand the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that are enabling as well as constraining the occupational performance of the community population. The person factors (intrinsic) include physiological, psychological, cognitive, neurobehavioural and spiritual influences on performance. The environmental factors (extrinsic) include cultural, social, natural environment, built environment and societal influences on performance. Clinical reasoning supports occupational therapists in applying their knowledge of the person, environment and occupational factors to the activities and tasks that are central to the community roles. At the community level many of the factors will be environmental. For example, the lack of an accessible playground for children, inadequate public transport to support older adults' community independence, and poor or confusing signage at the health centre would each represent environmental factors. However, there are also community problems that can affect the person (or intrinsic factors). Examples would include air quality, water quality, limited access to fresh food, and housing with lead paint.

Developing a client-centred plan to address occupational and related general goals for the population or community

With the client's information and the practitioner assessment of the client's capacity in hand, a client-centred plan can be developed. The client has the right to know and the practitioner has the responsibility to share the evidence that the interventions will be able to help the client achieve identified goals. Evidence will help the therapist understand the approaches that have already been tried to meet general and/or occupational goals and the outcomes of these various interventions. This step is important in determining strategies that work for this population/community, discarding ideas that do not have evidence to support them, and identifying intervention plans that have not yet been evaluated in the literature. If an untried strategy will be used, it is important for the client to understand the principles on which the therapist will base the intervention. The client must agree to the use of interventions proposed under such conditions.

Implementing a population-/community-centred intervention plan

If a therapist's work entails broad population/community initiatives and responsibilities (e.g. public health, labour, legislation), one may work with others to implement these strategies as part of an overall plan. If one's work involves developing partnerships with organizations and agencies, these overall strategies may serve as the foundation for a new situational analysis designed for organization-centred interventions.

Outcome of the plan

Following the implementation of the plan, the client hopefully will be able to achieve their goals. Outcomes should be measured, not only to demonstrate the progress to the client, but also to document the effectiveness of the occupational therapy interventions to the referral source, to other appropriate stakeholders, and to the public. The effectiveness of occupational therapy must be public in order to shape policies of institutions and payment sources.

Occupational performance and participation

The entire process leads to achieving the goals identified by the client and helping them achieve the goals that will improve the occupational performance of the population in their communities. Since many communities are facing new problems with an emerging population of older adults and many persons living with chronic diseases and disabling conditions, they need to provide the infrastructure to enable full participation of all members of the community. Part of the outcome should include the possibility of additional help from an occupational therapist if occupational performance issues emerge in the future that could benefit from an occupational therapist's expertise.

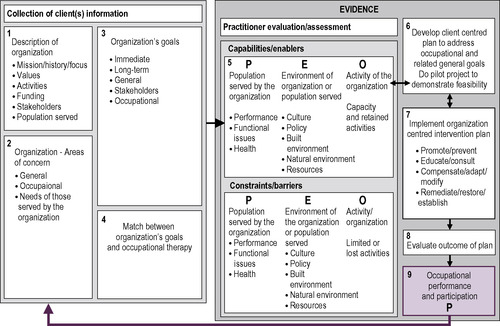

Planning organization-centred interventions

An organization situational analysis begins with an analysis of those served by the organization (Fig. 8.4). This step in the process enables the occupational therapist to approach the organization with a level of credibility that will open doors of opportunity. After developing expertise with regard to a specific population, an occupational therapist may not need to do this step in an explicit manner. Rather, the knowledge base of the professional includes this foundational information. Entry-level practitioners, however, would likely need to begin by determining an understanding of the population served by the organization as a preliminary step and prior to any discussions with a specific organization.

|

| Fig 8.4 • A situational analysis: using the PEOP Model for planning organization-centred interventions. Carolyn Baum, Julie Bass, and Charles Christiansen. Used with permission. |

The collection of client information

Description of the organization

Once there is an understanding of the population and of its needs, its resources and its goals, the next step in an organization situational analysis is a full description of the organization. An understanding of the organization's mission, history, focus, values, activities, funding, clients and stakeholders is essential for assessing their need and potential for occupational therapy services. Some of this information may be obtained in publications about the organization. Other information may be acquired through initial conversations with a contact person in the organization.

The organization's area(s) of concern

The occupational therapist begins to explore the organization's areas of concern and unmet needs for the clients they serve. Many of these concerns may be expressed in terms of general issues. For example, a community agency might be concerned about the adaptation of recent immigrants to the expectations of the larger culture. A school district may be concerned about the social and emotional health of some student groups. A corporation may be concerned about retention of workers who are mothers or caretakers. In this step, the occupational therapist also uses critical reasoning skills to identify and communicate the occupational issues that may be influencing the general areas of concern for the organization. For example, recent immigrants may have vocational backgrounds that are different from the work opportunities currently available, adolescents may only have access to extracurricular activities that are sport-related, and workers may not have sufficient support systems to solve parenting or caretaking problems as these arise.

The organizational goals

The goals of the organization and its stakeholders are considered next in the process. The occupational therapist enquires about the organization's immediate and long-term goals as they relate to general and occupational areas of concern. The practitioner also asks for information that will allow them to determine the organization's commitment and ability to achieve these goals.

The match between the organization's goals and occupational therapy

The final step in the first stage is to evaluate the match between the organization's goals and the occupational therapy services one can provide. The therapist will use population/community situational analysis, all the information gathered about the organization, and discussions with people in the organization to decide whether to continue the process. At this point, the therapist's personal investment in the organization has been limited. However, if one continues the process, the therapist and the organization may make a considerable commitment of personnel and resources for client assessment and interventions.

The evaluation and assessment of intrinsic (person) and extrinsic (environmental) factors that will impact on or support occupational performance

Selection of measures/assessments/methodologies to understand the intrinsic and extrinsic factors

The occupational therapist selects appropriate tools to understand the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that are enabling as well as constraining the occupational performance of the organization. The person factors (intrinsic) include physiological, psychological, cognitive, neurobehavioural and spiritual influences on the occupational performance of the organization's members. The environmental (extrinsic) factors include cultural, social, natural environment, built environment and societal influences on occupational performance. Clinical reasoning supports the occupational therapist in applying knowledge of the person, environment and occupational factors to the activities and tasks that are central to a community's roles. At the organization level many of the factors will be environmental. Examples might include the lack of training that fosters full participation of children in a mainstreamed classroom, managers who do not understand how to make accommodations for workers who wish to return to work after an accident or injury, or bus drivers' poor attendance related to lack of training. However, there are organizational problems that affect the person or intrinsic factors. Examples would be work practices that foster poor posture or repetitive motion injuries.

Developing a client-centred plan

With the client's information and the practitioner's assessment of the client's capacity, a client-centred plan can be constructed. The client has the right and the practitioner has the responsibility to share evidence that the interventions will be able to help the client achieve their goals.

Implementing an organization-centred plan

The therapist is now ready to develop an organization-centred intervention plan that can help the organization achieve its general and occupational goals. The therapist will want to consider initial population-/community-centred plan, variations of this plan that are appropriate for the organization, and the current evidence that is available. It also may be important to pilot any interventions, especially if this represents a new of area of occupational therapy practice. Pilot studies are a way to establish relationships with organizational clients, as initial outcomes can pave the way for additional work and funding. The organization will use the time to evaluate a therapist's capacity to help them achieve their goals. Implementation of the occupational therapy intervention plan may include any of the strategies identified in the person-centred situational analysis. However, promotion/prevention and education/consultation strategies are probably most common and effective when the target of an intervention involves an organization and its clientele.

Evaluating the outcome of the plan

The therapist's success with this organization can only be verified and documented if an evaluation of the effectiveness of the interventions is conducted, based on attainment of identified goals. This step is important in helping the therapist solidify their relationship with the organization. Additionally, it serves as a useful step in preparing a therapist to work with other related organizations. Disseminating the outcomes of interventions to the broader community is also essential for expanding practice into new arenas.

Occupational performance and participation

The entire process leads to achieving the occupational performance goals identified by the organization, with the possibility that such outcomes extend benefits to other clients they serve. Since many organizations are experiencing new problems with an emerging population of older adults, many of whom may be faced with chronic diseases and disabling conditions, they need to provide the infrastructure necessary to enable successful participation by clients in their organizations. Again, part of the outcome summary for the organizaton should include the possibility of providing additional help from an occupational therapist if occupational performance issues emerge in the future.

Summary

Three templates are provided to make explicit the activities that must come together to apply the PEOP Model effectively and appropriately. Occupational therapists have a widespread reputation for ‘doing good work’; however, because that work often employs ‘commonsense’ strategies, it is not always obvious that there is a systematic and complex thought process underlying intervention and that various sources of knowledge converge during decision-making to lead to specific recommendations. By using these templates, the practitioner is provided with appropriate language to use in reports and recommendations that will communicate the complexity of the process and the care that has gone into the resulting plan. In the end, we are confident that the templates provide a convenient means for applying the PEOP Model, so that individuals, communities and organizations can accomplish goals related to improved well-being and quality of life, despite the presence of conditions that otherwise limit or restrict occupational performance.

• How does the process of determining interventions differ between application to individual clients and application to groups?

• Reflect on the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic factors as they apply to an individual client and groups or organizations.

• Consider your own life. Given the activities that are important to your health and well-being, what intrinsic and extrinsic factors most influence your ability to participate in them?

References

Baum, C.; Bass, J.; Christiansen, C., Person-environment-occupational performance: A model for planning interventions for individuals and organizations, In: (Editors: Christiansen, C.; Baum, C.; Bass, J.D.) (2005) Slack Inc., Thorofare, NJ, pp. 373–392.

Baum, C.; Christiansen, C., Person-environment-occupational-performance: An occupation-based framework for practice, In: (Editors: Christiansen, C.; Baum, C.; Bass, J.D.) Occupational Therapy: Performance, Participation and Well-being3rd ed. (2005) Slack Inc., Thorofare, NJ, pp. 242–267.

Christiansen, C.; Baum, .C., Occupational Therapy: Overcoming Human Performance Deficits. (1991) Slack, Thorofare, NJ.

Christiansen, C.; Baum, C., Person-environment occupational performance: A conceptual model for practice, In: (Editors: Christiansen, C.; Baum, C.) Occupational Therapy: Enabling Function and Well-being2 ed. (1997) Slack, Thorofare, NJ, pp. 46–71.

Engel, G.E., The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine, Science 196 (4286) (1977) 129–136.

Meyer, A., The philosophy of occupational therapy, Archives of Occupational Therapy 1 (1) (1922) 1–10.

Reed, K.; Sanderson, S., Concepts of Occupational Therapy. 4th ed. (1999) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD.

Shannon, P.D., The derailment of occupational therapy, American Journal of Occupational Therapy 31 (4) (1977) 229–234.