14. The biomechanical frame of reference in occupational therapy

Ian R. McMillan

Overview

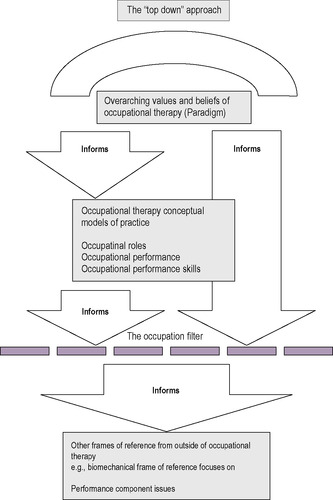

This chapter explains why studying a biomechanical frame of reference within occupational therapy is relevant in today's practice. The profession continues to have a contract with society to provide a service that focuses on human occupation. Occupational therapists are concerned with the relationship between people's occupations and their health, and assess people's disengagement from their occupations, provide ways for them to re-engage in their occupations, or suggest alternatives so that people's quality of life may improve. Core values and beliefs about the importance of occupation to humans constitute a paradigm of occupation. In daily practice, occupational role issues that individuals may experience can be appreciated by referring to conceptual models of practice using a ‘top-down’ approach. Examples of such models of practice are the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CMOP) (see Chapter 7 for further information) and the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) (see Chapter 6 for further information). Such models provide the knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to understand how we can analyse, intervene and evaluate individuals in relation to their roles and efficacy of occupational performances, e.g. in self-care, work and leisure. However, in order to understand the individual's specific occupational performance problems, it is also necessary to analyse and understand their ‘performance capacities’ in more detail. Performance capacities refer to cognition, behaviour, neural development, personal interactions and, most importantly for this chapter, movement. The biomechanical frame of reference deals exclusively with the capacity for motion, whilst other frames of reference deal with other capacities, e.g. the cognitive behavioural frame of reference deals with cognition and behaviour. A biomechanical frame of reference may be useful in assessment, intervention and evaluation with people who have occupational performance problems, created primarily by some disease, injury or event that impinges on their voluntary movement, muscle strength, endurance or usually a combination of all three. The loss of one or more of these capacities will interfere to some degree with an individual's ability to perform their occupations to their satisfaction. The biomechanical frame of reference assists in understanding the assessment, intervention and evaluation strategies associated with changing physical performance capacities in order to help individuals re-engage in their occupations.

• This chapter explores the evolution and use of a biomechanical frame of reference in occupational therapy.

• The biomechanical frame of reference can be located within a ‘top-down’ and a ‘bottom-up’ approach to occupational therapy.

• The biomechanical frame of reference deals with a person's problems related to their capacity for movement in daily occupations.

• The biomechanical frame of reference can be used to shape assessment, intervention and evaluation strategies, in order to help individuals re-engage in their occupations.

Introduction

The ‘biomechanical frame of reference’, in its original form, was not necessarily compiled by occupational therapists for occupational therapy practice today and therefore some translation of the original frame of reference (from a professional perspective) is necessary in order to ensure a ‘fit’ with the philosophy of occupational therapy. Therefore, this chapter describes and articulates a biomechanical frame of reference from an occupational therapist's perspective.

The biomechanical frame of reference used in occupational therapy has a long tradition and at different points in history has been termed Baldwin's reconstruction approach 1919, Taylor's orthopaedic approach 1934, and Licht's kinetic approach 1957 (Turner et al 2002). This frame of reference continues to be widely used today and different occupational therapists are continuing to present this frame of reference in different ways (for example, Trombly appears to have incorporated a biomechanical frame of reference into the Occupational Functioning Model; Trombly & Radomski 2002).

Reflecting on this biomechanical frame of reference (which encompasses a variety of knowledge, skills and attitudes) broadens a professional's knowledge base and provides more insight into fieldwork experiences and therefore an understanding of how practice can inform theory-building and vice versa.

Conceptual models of practice

Occupation (Kielhofner, 1997 and Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, 2002), within the context of occupational therapy, is part of the human condition, is necessary to society and culture, is required for physical and psychological well-being, entails underlying performance components and is a determinant and product of human development. Further, the intrinsic values of occupational therapy as a practice grounded in humanism affirm the dignity and worth of individuals, the participation in occupation, self-determination, freedom and independence, latent capacity, caring and the interpersonal elements of therapy, human uniqueness and subjectivity, and mutual cooperation in the therapeutic process. Occupation and occupational performance are usually expressed in terms of self-care/daily living tasks, work/productivity and leisure/play (Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, 2002 and Kielhofner, 2007).

This infers that studying and considering human occupation has to be paramount and is the core business of being an occupational therapist. When necessary, occupation can be analysed (e.g. the biological, psychosocial, environmental, etc.) regarding its content and meaning for the individual, to determine ‘dysfunctional elements’ that may occur because of disease and injury. Occupational therapists who can expertly analyse occupations are then able to perceive the meaning for that person and to assist them in regaining the necessary skills (or compensate for their permanent loss) through the medium of occupation and/or by modifying the environment or the attitudes of others in society and so on.

If an individual has temporarily or permanently lost an occupational role because of occupational performance problems primarily concerning movement, then the biomechanical frame of reference is likely to inform the therapist and assist the overall therapeutic process.

Ultimately, the majority of clients seen by an occupational therapist will have problems of ‘body and mind’ (irrespective of diagnostic labels), which can only be discerned within the context of that individual's environment, perspectives and value systems. This requires adopting a top-down approach to practice (Kramer et al 2003) by using an occupational therapy conceptual model of practice to appreciate the significance of an individual's occupational performance problems and then using the biomechanical frame of reference and others to appreciate the performance capacity issues.

Top-down approach to practice

The values and beliefs inherent in an occupation paradigm imply that occupational therapists need to view their clients as occupational beings. We therefore need to choose conceptual models of practice that focus on describing the occupational nature of the client. There are a number of unique occupational therapy models of practice available to choose from, such as the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) (Kielhofner 2007), the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CMOP) (Law et al 2005) and the Person–Environment–Occupation Model (Law et al., 1996 and Strong et al., 1999). Practice can then be further supported with other frames of reference when required (e.g. the biomechanical frame of reference), so that occupational performance issues relative to motion in occupations can be more specifically analysed and managed.

Figure 14.1 implies that the occupation paradigm influences every aspect of an occupational therapist's practice. The use of knowledge located in a biomechanical frame of reference needs to be filtered (occupation filter) by values that an occupational therapist embodies, which are located within the occupation paradigm. This ensures that the focus of interventions remains occupational in nature. The focus of the biomechanical frame of reference is the musculoskeletal capacity to create movement (range of motion), strength and endurance in order to carry out meaningful occupations. Movement, strength and endurance can then be assessed within the context of a person completing their occupations and using occupations to restore/maintain/compensate for lack of movement, strength and endurance.

|

| Fig. 14.1 • The ‘top-down’ approach. Reproduced with permission from Forsyth and McMillan, personal communication, (2001). |

Occupation filter

The following criteria constitute the occupation filter and occupational therapists ought to reflect on these statements when using the technology of the biomechanical frame of reference to enrich practice (Mallinson & Forsyth, personal communication 2000):

• Person's occupational performance. The primary concern here is understanding how the phenomena from the biomechanical frame of reference (movement, strength and endurance) influence the person's performance of their occupational roles.

• Assess through occupation. Analyse and assess the phenomena from the biomechanical frame of reference (movement, strength and endurance) within the context of the person's performance of their occupational roles.

• Occupation restores/maintains. This reinforces the person's performance of occupational roles during the restoration and/or maintenance and/or compensation of movement, strength and endurance.

• The outcome of occupational therapy is satisfying/meaningful performance in occupations. Occupational therapists ought to view the satisfying, meaningful performance of occupation as the primary outcome of therapy (Mallinson & Forsyth, personal communication 2000).

Using the top-down approach above implies that a biomechanical frame of reference used by an occupational therapist will be different from a biomechanical frame of reference used by other health professionals.

Occupation and occupational performance that incorporate movement and its potential restoration are the key to understanding the use of this frame of reference in our professional practice. Movement for the sake of movement is more likely to be the aim of other professionals, reflecting a bottom-up approach (Kramer et al 2003).

Details of the biomechanical frame of reference

The biomechanical frame of reference in occupational therapy is primarily concerned with an individual's motion during occupations. Motion in this context can be understood in more detail as the capacity for movement, muscle strength and endurance (the ability to resist fatigue).

An individual's quality of motion may be compromised as they carry out their occupations due to the effects of disease or injury. These effects may compromise specific body systems and structures (e.g. bones and joints) that help create motion seen during occupational performance. Additionally, an individual's quality of movement has to be viewed in the context of the environment that may facilitate or inhibit their occupations.

Aim and objectives

The biomechanical frame of reference aims to address the quality of movement in occupations. Specific objectives are to:

• prevent deterioration and maintain existing movement for occupational performance

• restore movement for occupational performance, if possible

• compensate/adapt for loss of movement in occupational performance.

Compensation and adaptation are terms that have often been associated with ‘rehabilitation’ or the ‘rehabilitative model’. Some practitioners believe the biomechanical frame of reference deals comprehensively with the topic of compensation and some believe that a rehabilitation model deals with compensation. This author believes that rehabilitation may be viewed as an ‘aim’ and that compensation is more comprehensively addressed within the biomechanical frame of reference.

Who would you use the biomechanical frame of reference with?

This frame of reference is principally used with individuals who experience the following problems in their daily occupations.

Limitations in movement during occupations

This describes the capacity of the person to use their muscles in conjunction with bones and joints to move freely when engaging in occupations. This is usually due to one or more of the following problems:

• shortening (contracture) of soft tissues, i.e. muscle tissue, muscle connective tissues, tendons, ligaments, fibrous capsules and skin

• the presence of inflammation, oedema or haematoma

• localized destruction of bone (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthrosis)

• amputation

• congenital abnormalities

• acute and chronic pain

• maladaptive environmental conditions.

Inadequate muscle strength for use in occupations

This describes the capacity of the person to initiate and maintain muscle strength during their occupations (e.g. using the forearm muscle groups to facilitate gripping an object effectively in the hand). Inability to do this may be due to one or more of the following problems:

• limitations in movement

• disuse or atrophy of muscle (e.g. post-fracture immobilization)

• primary muscle pathology (e.g. muscular dystrophy)

• anterior horn cell pathology (e.g. motor neurone disease)

• peripheral neuropathy (e.g. diabetes)

• peripheral nerve damage (e.g. mononeuropathy of the median nerve)

• acute and chronic pain

• maladaptive environmental conditions.

Loss of endurance in occupations

This describes the ability of the person to resist subjective fatigue and therefore sustain their occupations over time and distance to their satisfaction. Issues in this area are usually due to one or more of the following problems:

• limitations in movement

• inadequate muscle strength

• compromised cardiovascular and/or respiratory function

• acute and chronic pain

• maladaptive environmental factors.

Biomedical conditions

People who experience limitations in movement, inadequate muscle strength and loss of endurance whilst engaging in their occupations may have a diagnosis of one or more of the following biomedical conditions:

• rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthrosis or a combination of the two, or the individual may have experienced surgical arthroplasty

• amputations, burns and other soft-tissue damage frequently seen in hand and limb injuries

• fractures and various orthopaedic conditions

• Guillain–Barré syndrome, muscular dystrophy, motor neurone disease and the long-term effects of poliomyelitis (post-polio syndrome)

• peripheral neuropathy, mononeuropathy, brachial plexus lesions

• cardiac problems in the form of ischaemic heart disease (angina, myocardial infarction), cardiac failure or the effects of bypass surgery

• respiratory problems in the form of various obstructive airways diseases

• chronic pain due to occupational overuse syndrome (OOS), back injuries, neck injuries or pain associated with any of the conditions outlined above.

To appreciate the application of the biomechanical frame of reference fully implies an understanding not only of the biomedical conditions outlined above but also of the anatomical and physiological details of certain body systems and structures, which are outlined below:

• the musculoskeletal system, which comprises muscles, tendons, ligaments, bone and related tissues, and synovial joints (fibrous capsules, synovial tissues)

• the peripheral nervous system, comprising neural and connective tissues

• the integumentary system, comprising the epidermis, dermis, blood vessels, hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands

• the cardiorespiratory system, comprising the heart, blood vessels and lungs.

It should also be understood that, because the biomechanical frame of reference principally concerns the capacity to execute purposeful movement in everyday occupations, it is important to understand other factors that underpin this concept.

Other factors

It is helpful to have an understanding of the following factors. Understanding the biomechanical basis of movement includes knowing the locomotor system (how bones and joints perform together, especially in relation to the appendicular skeleton), active and passive joint range of movement (a.ROM and p.ROM), the function of skeletal muscle, types of muscle work (concentric and eccentric, isotonic and isometric contraction), muscle architecture and role, the peripheral nervous system (motor, sensory and autonomic) and the relationship between the peripheral nervous system (synaptic transmission and innervation) and muscles (sliding filament theory).

In addition, the biomechanical basis of movement includes understanding concepts of force, gravity, friction, resistance, leverage, stability and equilibrium, and how these elements interact to affect the nature of motion in human beings (Spaulding 2005).

The relationship between occupational performance and the biomechanical frame of reference requires understanding locomotion and the stance and swing phases of the gait cycle, prehension and the prehensile patterns of hand grips (power and precision), skeletal muscle and cardiovascular endurance, and the effects of fatigue on human occupations, all of which have to be considered for the execution of purposeful motion. Tyldesley and Grieve (2002) provide a detailed explanation of all of the above and this text is recommended as further reading to understand these factors in greater detail.

In summary, the capacity for movement (and occupational performance) is a synthesis of forces (the capabilities of the musculoskeletal system and the nervous system coordinating the work of groups of muscles to produce movement and stabilize joints) acting on the body. Endurance (the ability to sustain occupational performance) is predominantly a function of muscle physiology and the ability of the body systems to transport the required material towards, and waste materials away from, the muscle tissues.

Individuals' problems that can be addressed through the biomechanical frame of reference should have an intact, fully matured central nervous system. In other words, no evidence of biomedical conditions or pathology that might affect the following body systems should be evident:

• motor control systems (cortex/basal ganglia/cerebellum)

• sensory discrimination (cortex/thalamus/cerebellum)

• perceptual qualities (association areas of the cortex and parietal lobe functions)

• cognition (localization of function)

• behaviour (localization of function).

This is because the individual with movement problems described in the biomechanical frame of reference still has the capacity in their central nervous system to initiate the production of smooth, controlled isolated movements (Dutton 1998). This is in sharp contrast to individuals with central nervous system (CNS) damage who would have different types of motor problem and therefore a different frame of reference would have to be considered, i.e. the theoretical approaches to motor control and cognitive function (see Chapter 15 for further information). However, it is also apparent that occupational therapists do use the technology of the biomechanical frame of reference at certain times with selected individuals who do have CNS damage in the form of stroke, multiple sclerosis and so on. This is because, inevitably, some individuals do sustain permanent loss of the control of movement in various parts of their body, and in the long term compensating for this loss of motion in occupational performance is required.

The next part of this chapter concentrates on the assessment of movement seen in occupational performance.

Principles of assessment and measurement

Rationale for assessment

Occupational therapists ought to be concerned with the principles of assessment and measurement in their practice to facilitate collaborative goals, build intervention plans and document measures of outcomes. This process of assessment can be undertaken through client-driven assessment, therapist observation and the use of standardized and non-standardized instruments.

Assessment facilitates the collection of quantitative and qualitative data, which, when analysed, permit the interpretation of the effectiveness of an intervention by both the client and the therapist. This interpretative process, in relation to hard and soft data, assists in monitoring and implementing change, helps in building goals, facilitates decision-making and produces evidence that is readily understood, for the benefit of clients and of health professional and managerial colleagues.

General aims of assessment

The aims of occupational therapy assessment are generally agreed to:

• decide whether occupational therapy is appropriate or necessary

• establish abilities, disabilities and the effects of the environment on an individual's occupations

• formulate a package of information (data collection) to plan future goals

• formulate a baseline to compare progress and regress

• assist decision-making regarding the modification of intervention plans

• involve, inform, educate and motivate the individual (client)

• establish the efficacy (and evidence base) of occupational therapy intervention

• assist resource decision-making regarding demands on service provision

• produce tangible outcomes/evidence for the benefit of the individual and of healthcare and management colleagues.

Methods of assessment

In the context of the biomechanical frame of reference these may consist of:

• observation of occupational performances

• interviews (informal/unstructured through to formal/structured)

• questionnaires (open and closed questions)

• checklists (paper and pencil, computer)

• rating scales (paper and pencil, computer)

• performance evaluations (specific tasks, electrical, mechanical and computer equipment).

Framework for assessment and occupation

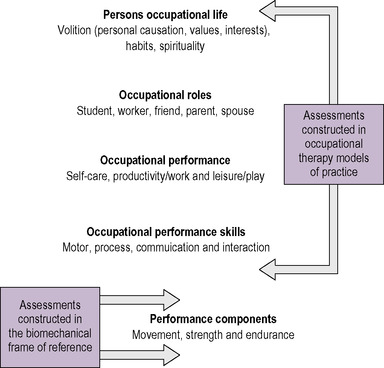

Assessments frequently reflect the theoretical perspectives of certain conceptual models of practice or frames of reference. It is important to reflect on which theoretical perspectives have informed the construction of assessments administered in practice. Although occupational therapists utilize a wide range of assessments, Mathiowetz, 1993 and Kielhofner, 2007 and Fisher (1998), all occupational therapists, assert that in concert with the values and philosophy of the profession, assessment ought to be focused on occupation, with a view to re-engaging the person in their occupations, and be as comprehensive as possible within the constraints of time. Because assessments have arisen from conceptual models of practice and frames of references, it is important to understand the difference between assessments constructed by occupational therapists and assessments constructed by others. These differences reflect varying professional philosophies and need to be understood, so that it is clear when to use multiple assessments appropriately.

Mathiowetz (1993) and more recently Molineux (2004) believe that a hierarchical order should be imposed on assessment, with occupational role and occupational performance being more important than the assessment of performance components. Mathiowetz (1993) advocated this approach (reflecting Kramer et al's (2003)‘top-down’ view) because he believed occupational therapists ought to be primarily concerned with the daily effects of loss of occupational performance, thus reflecting the importance of the link between individuals and occupations. Specific assessments, e.g. the Worker Role Interview (Braveman et al 2005) and the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) (Law et al 2005), would capture occupational performance as described above. However, Wilby (2007) also believes that performance components ought to be recognized in occupational therapy practice and that specific assessments are required in specialist areas of practice that are drawn from other frames of reference. This would help inform therapists about specific performance component issues that are the building blocks of occupational performance; that is, an occupational therapist would assess loss of movement, which influences occupational performances. This approach could be described as a ‘bottom-up’ approach (see Kramer et al 2003 for a detailed explanation of this terminology).

In summary, assessments are drawn from occupational therapy models first and then more detailed data about movement, strength and endurance (performance components) could also be collected using specific instruments to provide a comprehensive picture of the individual. Figure 14.2 reflects this approach.

|

| Fig 14.2 • Assessment and occupation. Reproduced with permission from McMillan and Forsyth (2001). |

Assessment of performance components for occupation

As previously mentioned, an area of expertise within the biomechanical frame of reference is to collect data from individuals, which provides greater detailed evidence to understand an individual's specific occupational performance problems. Because of the nature of the biomechanical frame of reference, assessments mostly relate to movement. There are various methods (mostly quantitative) available to assess occupational performance components in terms of movement, strength and endurance. The majority of these are readily available and can be easily applied with some practice. During the last few years there has been an increase in electronic and computer technology to assist the assessment process. Table 14.1 identifies specific testing procedures and sources of reference related to assessing the capacity for movement, strength and endurance. This table also details other factors, such as sensation (including pain) and other tests of function, which may fall within the remit of the biomechanical frame of reference.

| *The management of pain as part of the biomechanical frame of reference is a contentious issue. Pain is a perception (not merely a sensation) formulated in the cerebrum and is therefore within the remit of a different frame of reference; however, pain can be apparent in a multitude of conditions that fall within the remit of the biomechanical frame of reference and affect the occupational performance of individuals. | |

| Test | Reference |

|---|---|

| Movement | |

| Range of motion (ROM) in joints | |

| Observation | Pedretti & Early (2001) |

| Goniometry | Neistadt & Crepeau (1998) |

| Odstock method | Roberts (1989) |

| Strength | |

| Muscle power | |

| Oxford Rating Scale | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

| Other scales | Neistadt & Crepeau (1998) |

| Grip strength in the hand | |

| Dynamometer | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

| Pedretti & Early (2001) | |

| Pinch strength in the fingers | |

| Pinch meter | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

| Muscle bulk | |

| Observation | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

| Tape measure | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

| Presence of swelling in limbs | |

| Observation | Turner et al (2002) |

| Tape measure | Neistadt & Crepeau (1998) |

| Volumeter | Pedretti & Early (2001) |

| Endurance | |

| Observation | Neistadt & Crepeau (1998) |

| Cardiorespiratory | Neistadt & Crepeau (1998) |

| Functional | Neistadt & Crepeau (1998) |

| Sensation | |

| Light touch and pressure | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

| Weinstein monofilament | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

| Thermal sensation | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

| Pain* | Trombly & Radomski (2002) |

Assessment of specific performance components

Occupational therapists frequently use tests of ‘function’. These tests tend to examine performance components related to the upper limb and especially power and precision grips of the hand. Examples of these include (Turner et al 2002):

• Bennett Hand Tool Test

• Jebsen–Taylor Hand Function Test

• Moberg Pick Up Test

• Valpar Work Samples.

Principles of intervention

The principles of intervention located in a biomechanical frame of reference should reflect the philosophy and values of our profession. This implies filtering the knowledge associated with the biomechanical frame of reference through the occupation paradigm. Therefore, the philosophy and values of occupation provide the rationale for coherent principles, skills and techniques that are applied to meet the needs of individuals, with regard to movement and occupational performance problems.

Occupation in therapeutic intervention

Occupational therapy intervention varies considerably in terms of contact time with individuals. This may range from performing an assessment and discharge planning service (1 day) to constructing programmes where the individual may be seen by you for longer periods of time (especially on an outpatient basis). This helps distinguish, to some extent, practice that attempts to restore, maintain or compensate for ‘lost’ (temporarily or permanently) occupational performance. The use of meaningful occupation energizes intervention and defines the unique philosophy of occupational therapy (Trombly, 1995, Ferguson and Trombly, 1997, Fisher, 1998 and Perrin, 2001). In summary, principles related to the quality of movement, intervention techniques and meaningful occupation are blended together to manage the problems that the individual experiences. This usually relates to restoring (or compensating) an individual's physical performance in terms of movement, strength and endurance in order to carry out tasks in self-care, work and leisure in different contexts of practice.

Practice settings

Occupational therapists tend to be employed in different practice settings, and usually these are denoted by specialized areas of expertise. The application of techniques associated with the biomechanical frame of reference is usually experienced within the following areas of practice:

• amputation and amputee problems

• assistive technology (wheelchairs, orthotics and other devices for home and personal use)

• burns and plastic surgery

• cardiac rehabilitation

• general medical problems

• hand therapy

• housing (ergonomic) modifications in the community

• older people (usually problems with falls, stability and mobility)

• orthopaedics

• orthotics and prosthetics

• pain management

• spinal cord injury

• work rehabilitation

• worksite modification.

All of the above may take place in hospital or community settings.

In order to link the theory described in this chapter clearly with practice, the next part of this chapter will illustrate the use of the biomechanical frame of reference with a hypothetical case study of a person who has difficulties in her daily life with some occupational performances.

Ms A

Ms A is a 40-year-old woman who currently lives independently in her own apartment, with a very supportive partner. She has a 5-year history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and reports that the main effects of her condition on her occupational lifestyle are fatigue at work and some experience of pain.

Ms A is employed full-time in an office as a clerical assistant, mainly using a computer for multiple tasks in her worker role.

She still pursues leisure interests in terms of socializing with friends, reading and listening to music, but has given up skiing, cycling and generally keeping fit.

Ms A appears to manage (in her own words) her occupational roles; however, she does report having some minor difficulties during an initial interview with the occupational therapist.

Assessment

The occupational therapist could utilize various rigorous assessments drawn from MOHO (Kielhofner 2007) or use the COPM (Law et al 2005) to collect self-report data regarding occupations. Assessments related to movement, strength and endurance are then administered to collect objective data on specific performance components. Based on the client's perceived problems (from the selected occupational therapy conceptual model of practice assessments) and objective assessments from the biomechanical frame of reference, the following is apparent:

• Occupational roles. No major concerns expressed at this time in terms of fulfilling her role expectations of being a partner, daughter, worker and friend.

• Occupational performance. No self-care problems evident except in relation to heavy housework (lack of endurance). Work and productivity (especially using a computer keyboard) provoke more anxiety in terms of future capability. Leisure is not reported as being problematic.

• Occupational performance skills. Problems at times in terms of mobility, reaching, bending, manipulating and endurance in her occupations.

• Occupational performance components. Objective findings related to loss of muscle bulk, strength, hand grip and overall endurance.

• Environment. Problems with work environment, attitudes towards her productivity and minor problems in her home environment.

Intervention

The aim of the biomechanical frame of reference in this case study is to address the quality of movement in Ms A's occupations. General objectives relative to Ms A are to:

1. prevent deterioration and maintain existing movement for occupational performance (computer usage at work, joint protection techniques and acknowledging/managing pain)

2. restore movement for occupational performance, if possible (improving muscle strength)

3. compensate/adapt for loss of motion in occupational performance (energy conservation techniques and using assistive technology).

It should be noted that, whilst individual objectives are documented above, all three objectives are probably being addressed simultaneously when Ms A engages in any occupation in a therapeutic manner.

Using computers at work

Ms A uses a computer at her work every day and therefore the topic of ergonomics is relevant to her situation. Ergonomics is the application of scientific information concerning human beings to the design of objects, systems and environments for human use (Pheasant 1991).

This subject is principally associated with the design of everyday objects in the environment, and, in this case, analysing the computer at the point of interaction with Ms A, to prevent OOS, postural deformity, excessive fatigue and pain, whilst also ensuring safety.

In relation to occupational performance in its widest context, occupational therapists should be concerned with biological efficiency, health and safety in the home and workplace, and the comfort and ease of use of objects (Nicholson, 1999 and Hignett, 2000). The College of Occupational Therapists has produced a vocational rehabilitation strategy (2008) and this document would provide more information on this important role for an occupational therapist intervening with Ms A.

OOS is defined as those disorders that are caused, precipitated or aggravated by repeated exertions or movements of the human body. It involves a number of similar conditions arising from overuse of soft tissues (tendons, muscles, nerves, vascular structures), usually of the upper limb, and is due to repeated ‘micro trauma’ rather than sudden instant injury (McNaughton 1997). Ms A may be at risk of developing OOS because of repetitive or prolonged keyboard use, awkward postures due to poorly designed chairs, localized contact stress on her forearms and hands due to the table edge and poorly designed work stations in general. Ms A may complain of stiffness, discomfort, pain, alteration in sensation and clumsiness because of OOS, in addition to the problems associated with rheumatoid arthritis. In response, intervention may be delivered in terms of altering the ergonomics of her computer work station and reinforcing the following elements.

Chair

Ensure that Ms A uses the correct chair, which should have a five-spoked base with castors and an adjustable backrest. The backrest angle should be adjusted to 110%, and ought to support her lumbar region up to the inferior aspect of her scapulae. Adjust her chair for height; when her fingers are placed on the keyboard, her forearms ought to be roughly parallel with the floor. Ensure that her feet are firmly placed on the floor with her knee angle at roughly 90–110%. If her feet are not touching the floor, use a footrest (a strong ringbinder would suffice if cost is an issue for her employer). Some space between the top of the thighs and the underside of the desk ought to exist.

Work station

Adjust the position of Ms A's monitor by ensuring that her feet are flat on the floor and her head is in the midline; when she is looking straight ahead, the top of the screen should be at or just below eye level height. The monitor should be at least 18–30 inches from her eyes (arm's length). The posture of her hands on the keyboard is important. Preferably, the hands and wrists should be neutral relative to the forearm (no excessive flexion, extension, or radial or ulnar deviation). Instruct her to hold the mouse loosely and to avoid resting the forearm or wrist on the edge of the desk. Discourage hyperextending the little finger and advise her to use a light touch when clicking the mouse. Use work-station devices, e.g. a copy stand or document holder, a gel wrist rest, a gel mouse mat, a lumbar roll if necessary, and a footrest and telephone headset if appropriate. Check her arc of reach on the desk when seated and place important objects to hand to prevent overstretch (Jacobs & Bettencourt 1995).

Lighting

Try to reduce glare on the computer screen by placing the monitor at right angles to a window (light source), if possible, using blinds on windows if these are fitted. Tilt the monitor slightly so that overhead lighting does not create screen glare. Use the brightness, colour and contrast controls on the monitor to compensate for glare.

Posture

Encourage Ms A to take frequent breaks from keyboarding, by varying her routines and walking about to perform other tasks, e.g. a 30-second break every 10 minutes.

The same advice would be applied to Ms A if she also uses a computer at home for work or leisure. You should consult Holmes (2007) for further information on vocational rehabilitation.

Joint protection and occupational performance

Joint protection is principally an educational and training programme used in conjunction with connective tissue diseases, and has historically been utilized in the management of rheumatoid disease in the upper limb. The principles are designed to teach Ms A about the inflammatory process and potential deformities seen in rheumatoid arthritis (Hammond, 1997 and Hammond and Lincoln, 1999). Instruction in joint protection techniques addresses the following points:

• reducing joint stress

• decreasing pain

• preserving joint structure

• maximizing occupational performance and conserving energy.

Ms A will require careful instruction, so that joint protection techniques can be consistently employed in all of her occupations to maintain maximal capacity for motion and to prevent damage and long-term deformity.

Seven principles of joint protection are outlined below in title only, and further research is recommended in order to understand fully the detail required for implementing each of these principles before instructing Ms A in their application. The detail regarding these principles can be found in most occupational therapy textbooks related to physical dysfunction (e.g. Pedretti & Early 2001):

• Respect pain at all times.

• Maintain muscle strength and joint range of movement.

• Avoid positions of deformity and deforming stress.

• Use each joint in its most stable, anatomical and functional position.

• Use the strongest joints available for the activity.

• Avoid using muscles or holding joints in one position for any undue length of time.

• Never begin an activity that cannot be stopped immediately.

The success of these techniques with Ms A depends on the need for education in terms of teaching her about preventing deterioration or maintaining her present occupational performance. Occupational therapists are constantly required to reinforce existing knowledge or impart new skills, which may alter habits in some way to facilitate change. In relation to Ms A, the key to learning (and teaching) involves using the techniques in conjunction with her occupational performances in self-care, work and leisure that she has identified as problematic. Effective learning methods also imply planning ahead, imparting information at the correct level, providing clear instructions, eliciting feedback, evaluating learning, promoting the highest level of learning and using different methods to impart new information (French et al., 1994 and Neistadt and Crepeau, 1998).

Ms A may also have a problem with chronic pain. Although it is beyond the remit of this chapter to deal with the extensive information about the management of chronic pain, attention to computer usage, joint protection techniques and pacing during occupations may help to change the perception of chronic pain. Tyldesley and Grieve (2002) give further information regarding the occupational therapist's role in the management of pain and also present a related case study.

Improving muscle strength

Muscle strength is the amount of force that can be exerted by a single muscle or groups of muscles in a voluntary contraction. Muscle strength can be seen in isometric and isotonic activity, both of which are required for occupational performance. There is a relationship between the recruitment of motor units and the production of maximum muscle tension in response to external loads on muscle groups. Periods of muscular inactivity due to disease or trauma may lead to muscle atrophy (decreased strength), the inability to sustain performance and a loss of co-ordination during occupational performances. In order to increase muscle strength, stress (demand) has to be applied to a muscle through the use of occupational performances in order that all the motor units are recruited to maintain and restore the muscle. This activity will ensure maximum (or near-maximum) contraction of the muscle, thus hypertrophying muscle fibres by influencing changes in the amount of contractile proteins. An increase in the amount of proteins and cross-bridges improves muscle cross-sectional size and therefore strength (Jackson et al 2002).

Hypothetically, muscle tension needs to reach 50–67% of the maximum potential capability of that muscle or group of muscles, and an increase in strength will result. This implies that, as the muscle increases in strength, the amount of stress placed upon it should also be increased over time, to increase strength further. This is termed the ‘overload principle’ and requires grading of stress through occupations, placed on the client's affected muscle groups over time. Overloading is a positive stressor and will improve adaptation to the demands placed on Ms A when carrying out her self-care, work and leisure performances. Trombly & Radomski (2002) argue that occupation as a means of therapeutic change and occupation as an end result have to be apparent to the individual.

Muscle strengthening (through overloading) involves the analysis and grading of occupation and is dependent on the following factors:

• type of occupation (self-care, work/productivity and leisure)

• intensity (resistance of muscles against the performance)

• duration (time taken to complete the occupation)

• speed (of the limbs and so on during the occupation)

• frequency (how often the occupation is undertaken).

Occupations should be motivating and have meaning for Ms A in relation to her occupational performances. The most important factor other than the occupation itself is the intensity, which concerns the muscle groups being resisted whilst attempting to produce motion for occupation. Resistance can be altered by changing the position of Ms A relative to the occupation, changing the length of lever arms, changing the materials used, increasing the difficulty of the occupation, using different tools, and changing the weight of any objects used for the occupation.

Engaging in occupational performance is usually aimed at restoring muscle strength and improving motion in one area of the body: for example, the upper limbs. However, in order to carry out her desired occupations in a sustained fashion, Ms A's muscular (whole-body) endurance also has to be improved. For example, this could be attained by looking at the weight of the clothes that she loads into her washing machine and gradually increasing that load over time. The ‘reserve’ of the cardiorespiratory system in resisting fatigue is then considered as part of the occupation. Pedretti (1996) provides further detail on increasing cardiorespiratory reserve.

Energy conservation

Energy conservation techniques are generally used in the management of chronic pathological conditions in which strength and particularly endurance are compromised. This implies compensation on a temporary or permanent basis. The aims of the techniques are to eliminate wasted body motion in order to preserve physical and psychological energy resources. This is especially the case when Ms A perceives a relapse in the clinical course of her condition of rheumatoid arthritis.

Ms A could be instructed to reduce energy expenditure (physical and psychological) by planning ahead, organizing storage in the home and at work, sitting to perform kitchen work instead of standing where possible, reducing the weight of briefcases, bags of shopping and so on, and ensuring good working conditions with respect to lighting, ventilation and heating.

She could also utilize alternative sources of energy (human resources and assistive technology devices) by asking her partner, immediate family and relatives to undertake certain tasks for her at times (shopping, laundry, vacuuming). In the longer term, if her condition did deteriorate, then volunteer and ‘home help’ services (ironing, laundry, etc.) would be worth considering.

Assistive technology and occupational performance

This section describes technology that can help an individual maintain, restore or compensate for loss of occupational performance.

Assistive technology can be utilized over short or long periods of time, depending on the client's potential for restoration or compensation. Assistive technology in its simplest form includes personal and domestic devices: for example, adapted cutlery, plates, easy chairs, dressing devices, communication devices, bath boards, kitchen devices and manual wheelchairs. Some of these simpler devices may be appropriate for Ms A at certain times. On a more complex level, static and dynamic orthoses, prostheses, burn pressure garments, electric wheelchairs, stair lifts, adapted vehicles and environmental control systems can also be viewed as assistive technology (Van Schaik 2000, Weilandt & Strong 2000).

One aspect of assistive technology that may assist Ms A temporarily is the use of a wrist–hand orthosis or splint. Orthotics (or splinting) involves the design, manufacture and application of thermoplastic material to manage individuals' biomechanical problems. Although thermoplastic orthoses can potentially be applied to any area of the body, occupational therapists most often apply orthoses to the prehensile structures, i.e. the hand and upper limb, and locomotor structures, i.e. the foot and lower limb.

In general, orthoses are biomechanical in design and are used to manage problems associated with limitations resulting from problems of the musculoskeletal system, peripheral nervous system and integumentary system. Despite the different designs (static and dynamic orthoses) and materials, orthoses are generally used to meet the following aims, dependent on the individual's problems:

• to achieve an optimal anatomical position and physiological state, therefore maximizing functional ability

• to provide pain relief

• to facilitate correct anatomical healing

• to prevent and correct soft-tissue deformity

• to maintain the function of unaffected parts

• to maintain the improvements achieved by other forms of treatment

• to restore or maintain joint alignment and stabilization

• to assist the function of weak muscles and prevent overstretch

• to provide a substitution for absent muscle power

• to protect vulnerable anatomical structures.

In addition to the skill of manufacture and application, comprehensive assessment procedures and specific knowledge regarding the musculoskeletal structures necessary for motion are necessary. Effective management of problems by the application of orthoses depends as much on efficient manufacture as the clients' attitudes to wearing the device. Individuals like Ms A have to understand why wearing the orthosis is important, this being accomplished through educational principles, which are the key to successful management and treatment. See Coppard and Lohman (2001) for further information about orthoses.

Summary

Some occupational therapists have argued that a biomechanical frame of reference is essentially reductionist and narrow in its focus, because it is based on a biomedical view of the world (Turner et al 2002). However, this stance reflects a ‘bottom-up’ approach to practice, and occupational therapists who attempt to use the technology of the biomechanical frame of reference in isolation from occupational therapy conceptual models of practice will certainly find its usage frustrating.

In isolation, the biomechanical frame of reference is not universally applicable to every individual, even those with movement problems; however, the management of any individual (e.g. Ms A) will always require a blend of conceptual models of practice and frames of reference. For example, the successful management of Ms A will require knowledge about occupational therapy conceptual models of practice, the biomechanical frame of reference and probably the cognitive behavioural frame of reference (see Chapter 12 for further information) in order to address problems of occupational performance created by conditions that affect mind and body together.

Ultimately, it is not necessarily the theoretical base of a specific frame of reference that makes it narrow in application, but one's view of the world as an occupational therapist and how different conceptual models of practice/frames of reference are used to address the multiple needs of an individual like Ms A.

Areas for future research

Kielhofner (2009, p.76) documents the following areas of current interest in the application of a biomechanical frame of reference in occupational therapy:

• the relationship between musculoskeletal capacity and success in occupations

• muscle action and movement patterns used in different task conditions

• how the purpose and meaning of activities affect therapy compliance, effort, fatigue and improvement in movement capacity.

Summary

Kielhofner (2009, p.79) concludes that the biomechanical model is a unique model of practice in occupational therapy and states:

Given the centrality of movement problems in occupational therapy clients and the long history of this approach in occupational therapy practice, there is no doubt that the [biomechanical] model will continue to be a vital part of occupational therapy science and practice.

• What features make a biomechanical frame of reference different from other frames of reference in this book?

• Which areas of human performance does a biomechanical frame of reference help you understand as an occupational therapy student?

• In what ways could a biomechanical frame of reference inform you how to assess and intervene with people who have issues in their daily occupations?

• What would be the consequences of assuming that a biomechanical frame of reference could be applied in isolation from models and other frames of reference in occupational therapy?

• Reflect on your most recent practice experiences. In what ways could you have enriched the interventions that you undertook with individuals with movement problems in their daily occupations?

References

Braveman Braveman, B.; Robson, M.; Velozo, C.; et al., Worker Role Interview (WRI). (2005) MOHO Clearing House, Chicago.

Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, Enabling Occupation: An Occupational Therapy Perspective. (2002) Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, Ottawa.

College of Occupational Therapists, Vocational Rehabilitation Strategy. (2008) College of Occupational Therapists, London.

Coppard, B.M.; Lohman, H., Introduction to Splinting: A Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Approach. second ed (2001) Mosby, St Louis.

Dutton, R., Biomechanical frame of reference, In: (Editors: Neistadt, M.E.; Crepeau, E.B.) Willard and Spackman's Occupational Therapyninth ed. (1998) Lippincott, Philadelphia.

Ferguson, J.M.; Trombly, C.A., The effect of added-purpose and meaningful occupation on motor learning, American Journal of Occupational Therapy 51 (7) (1997) 508–515.

Fisher, A.G., Uniting practice and theory in an occupational framework, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 52 (7) (1998) 509–521.

French, S.; Neville, S.; Laing, J., Teaching and Learning: A Guide for Therapists. (1994) Butterworth–Heinemann, Oxford.

Hammond, A., Joint protection education: what are we doing?British Journal of Occupational Therapy 60 (9) (1997) 401–406.

Hammond, A.; Lincoln, N., The Joint Protection Knowledge Assessment (JPKA): knowledge and reliability, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 62 (3) (1999) 117–122.

Hignett, S., Occupational therapy and ergonomics: two professions exploring their identities, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 63 (3) (2000) 137–139.

Holmes, J., Vocational Rehabilitation. (2007) Blackwell, Oxford.

Jackson, J.; Gray, J.M.; Zemke, R., Optimizing abilities and capacities: range of motion, strength and endurance, In: (Editors: Trombly, C.A.; Radomski, M.V.) Occupational Therapy for Physical Dysfunctionfifth ed. (2002) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

Jacobs, K.; Bettencourt, C.M., Ergonomics for Therapists. (1995) Butterworth–Heinemann, Boston.

Kielhofner, G., Conceptual Foundations of Occupational Therapy. second ed. (1997) FA Davis, Philadelphia.

Kielhofner, G., Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application. fourth ed. (2007) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

Kielhofner, G., Conceptual Foundations of Occupational Therapy. fourth ed. (2009) FA Davis, Philadelphia.

Kramer, P.; Hinojosa, J.; Royeen, C.B., Perspectives in Human Occupation: Participation in Life. (2003) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

Law, M.; Cooper, B.; Strong, S.; et al., The Person–Environment–Occupation Model: a transactive approach to occupational performance, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 63 (1) (1996) 9–23.

Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; Carswell-Opzoomer, A.; et al., Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. fourth ed (2005) Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, Toronto.

Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; Carswell, A.; et al., Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. (2005) CAOT Publications ACE, Toronto.

Mathiowetz, V., Role of physical performance component evaluations in occupational therapy functional assessments, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 47 (3) (1993) 225–230.

McNaughton, A., Occupational overuse syndrome/repetitive strain injury: the occupational therapist's role, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 60 (2) (1997) 69–72.

Molineux, M., Occupation for Occupational Therapists. (2004) Blackwell, Oxford.

Neistadt, M.E.; Crepeau, E.B., Willard and Spackman's Occupational Therapy. ninth ed. (1998) Lippincott, Philadelphia.

Nicholson, J., Management strategies for musculoskeletal stress in the parents of children with restricted mobility, British Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 62 (5) (1999) 206–212.

Pedretti, L.W., Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction. fourth ed (1996) Mosby, St Louis.

Pedretti, L.W.; Early, M.B., Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction. fifth ed. (2001) Mosby, St Louis.

Perrin, T., Don't despise the fluffy bunny: a reflection from practice, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 64 (3) (2001) 129–134.

Pheasant, S., Ergonomics, Work and Health. (1991) MacMillan, London.

Roberts, C., The Odstock Hand Assessment, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 52 (7) (1989) 256–261.

Spaulding, S.J., Meaningful Motion: Biomechanics for Occupational Therapists. (2005) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Strong, S.; Rigby, P.; Stewart, D.; et al., Application of the Person–Environment–Occupation Model: a practical tool, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 66 (3) (1999) 122–133.

Trombly, C.A., Occupation: purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 49 (11) (1995) 960–972.

Trombly, C.A.; Radomski, M.V., Occupational Therapy for Physical Dysfunction. fifth ed. (2002) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

Turner, A.; Foster, M.; Johnson, S.E., Occupational Therapy and Physical Dysfunction: Principles, Skills and Practice. fifth ed. (2002) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Tyldesley, B.; Grieve, J.I., Muscles, Nerves and Movement in Human Occupation. third ed. (2002) Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Van Schaik, P., Adapted technology for people with special needs: the case of smart cards and terminals, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 63 (3) (2000) 111–114.

Wielandt, T.; Strong, J., Compliance with prescribed adaptive equipment, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 63 (2) (2000) 65–75.

Wilby, H.J., The importance of maintaining a focus on performance components in occupational therapy practice, British Journal of Occupational Therapy 70 (3) (2007) 129–132.