Chapter 59Flexural Limb Deformities in Foals

Flexural limb deformity is the inability to extend a limb fully. Generally hyperflexion of a region results from a disparity in the length of the musculotendonous unit relative to the length of the bone. The deformities are categorized as congenital or acquired and may occur during in utero development or at any time after birth. Different anatomical structures may be involved, including the digital flexor tendons, suspensory apparatus, joint capsule, and surrounding fascia, skin, and bone.1-6

Congenital Flexural Deformities

Congenital deformities are present at birth, and the cause is often unknown. Although uterine malposition of the fetus is often discussed, because of the voluminous nature of the uterus and the ability of the foal to move, uterine malposition is an improbable cause of flexural deformity in most instances. Other documented causes include exposure of the mare to influenza and ingestion of Sudan grass, locoweed, or other teratogenic agents during development of the fetus.2,3,7 Equine goiter, neuromuscular disorders, and defects in elastin formation or collagen cross-linking may be involved in the pathogenesis.

Congenital flexural deformities most commonly involve the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, carpus, tarsus, and metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal joints, singularly or in combination.2 Both forelimbs are usually involved, and occasionally other variations of skeletal deformities are evident, such as hindlimb deformity (windswept), spinal deformity, rye nose, and cleft palate. Sporadically occurring deformities involving the scapulohumeral, cubital, coxofemoral, or femorotibial joints may occur in combination with other congenital skeletal anomalies. Congenital flexural deformities are a common cause of dystocia in the broodmare, resulting in loss of the foal and subsequent reproductive loss of the mare.

Treatment for congenital flexural deformities varies with the anatomical location involved and severity of the condition. Therapeutic intervention for foals with severe flexural deformities associated with arthrogryposis or gross spinal deformities should be discouraged, and humane destruction is recommended. Surgical transection of the digital flexor tendons and palmar carpal fascia generally fails to alleviate this deformity. Splinting and casting is also futile, although rarely a foal has survived with limited athletic potential.

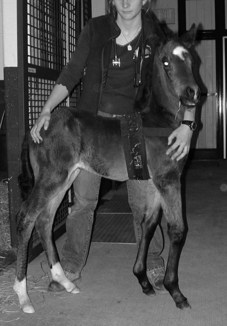

Mild flexural deformities of the carpal, metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal, or DIP joints resolve spontaneously if the foal has the ability to stand, nurse, and ambulate on its own. Most foals with mild and moderate deformities of these sites respond favorably to physiotherapy, by manually extending the limbs every 4 to 6 hours for 15-minute sessions, or forcing the foal to ambulate (Figure 59-1). Heavy bandaging, splinting or casting, and the administration of oxytetracycline can be helpful.2,8 Foals with deformities advanced enough to require assistance to stand respond more rapidly after application of a cast, which should be changed every 2 to 3 days (Figure 59-2). If a carpal deformity severe enough to prevent standing is recognized at parturition, the foal should be heavily sedated, within 30 to 45 minutes, and full-leg casts should be applied with the limbs placed in extension. These should be changed within 24 hours and reset. Generally a rapid response is seen after the first or second application of casts. If the foal develops any complications with the casts or becomes distressed, casts should be removed. Commercially available articulating braces (Almanza Corrective Boot, www.redboot.com.ar/home.html; Equine Bracing Solutions, Trumansburg, New York, United States; Dynasplint Systems, Serverna Park, Maryland, United States) are available and allow adjusting the degree of extension in a specific region of the limb (Figure 59-3). As with all splints, caution must be exercised to prevent pressure sores. It is important to assist the foal in nursing and to provide supportive care in an intensive neonatal facility, because these horses are at high risk for developing complications with other body systems.

Fig. 59-1 Mild bilateral flexural deformity of the carpus. This degree of deformity is self-limiting.

Oxytetracycline (2 to 4 g) administered slowly intravenously is also beneficial, but it should not be used in a neonate until serum creatinine is within normal limits.8 Oxytetracycline may be given daily or every other day for three or four treatments. Complications of oxytetracycline administration include renal failure, diarrhea, and, most commonly, excessive laxity of other, normal joints. The precise mechanism of action for tendon relaxation remains speculative.

Flexural deformity of the DIP joint is most often self-limiting if the foal can stand without buckling forward. Bandaging of the lower limb, physical therapy, and administration of oxytetracycline hastens recovery. If the foot angle is beyond 90 degrees (i.e., the dorsal aspect of the foot is in front of the vertical), casting or splinting may be necessary. Toe extensions are generally counterproductive and hinder ambulation of the foal.

Splints may be constructed from polyvinyl chloride (PVC) material, fashioned from fiberglass cast material, or purchased commercially. When splints are used for management of flexural deformity, the clinician must exercise extreme caution to prevent rub sores or pressure sores. Splints should be applied only for brief periods, in a schedule such as 4 to 6 hours on followed by 4 to 6 hours off. Properly applied casts are more effective, require less maintenance, and result in fewer pressure sores than splints.

Prognosis for future athletic performance is good for foals with congenital flexural deformities that respond favorably in the first 2 weeks of life. In general, if the foal is able to stand, nurse, and ambulate without assistance, most congenital flexural deformities are self-limiting and warrant a good prognosis. Foals may require several months to stop buckling dorsally at the carpus. Foals with flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal joints typically respond within the first or second week of life. Prognosis for future performance is poor for foals with severe flexural deformity of the carpus, tarsus, or metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal joints that show no improvement after several days of treatment and have difficulty ambulating without assistance after 1 to 2 weeks of treatment. Foals with congenital flexural deformities involving the scapulohumeral, cubital, coxofemoral, or femorotibial joints have a poor prognosis for future athletic performance.

Acquired Flexural Deformities

Acquired flexural deformities develop after birth until the second year of life. Commonly involved areas include the DIP joint, metacarpophalangeal joint, and carpus. Acquired flexural deformity of the DIP joint is recognized at 3 to 6 months of age, carpal flexural deformity is seen at 1 to 6 months of age, and flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal joint is recognized later, during the yearling or early 2-year-old year (9 to 18 months).9

Common causes of flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal joint and carpus are believed to include a genetic propensity for rapid growth, overnutrition, and pain. Relative excess feeding or overassimilation of nutrients in foals that have an inherent potential for rapid physical development is a frequent finding in foals with acquired flexural deformity, especially involving the carpus and the metacarpophalangeal joint. During periods of rapid bone lengthening the potential for passive elongation of the tendonous unit is limited because of the accessory ligaments, and a discrepancy in the length of the bone-to-tendon unit may result. Another theory is that a pain-mediated response during physeal dysplasia results in altered load bearing on the limbs. This is believed to initiate secondary contraction and shortening of the musculotendonous unit, resulting in limited extension of a region. Any cause of pain resulting in prolonged reduced weight bearing in a limb may result in this syndrome.

Genetics may be involved with the development of acquired flexural deformity of the DIP joints (club feet). Other factors include diet and exercise. Protracted lameness from another cause such as osteochondrosis of the upper limb also predisposes to development of acquired DIP joint deformity. It is therefore important to identify an associated source of lameness.

Early clinical signs of acquired flexural deformity of the DIP joint consist of a prominent bulge at the coronary band, increase in length of the heel relative to the toe, and failure of the heel to contact the ground after trimming (Figure 59-4, A). Eventually the foot develops a boxy shape with a dish shape along the dorsal hoof wall. This deformity is commonly accompanied by a back-at-the-knee (calf-knee) conformation (see Figure 59-4, B).

Fig. 59-4 A, Advanced flexural deformity of the right front distal interphalangeal joint. The heel does not contact the ground, and the dorsal aspect of the hoof wall is dish shaped. B, Calf-kneed conformation is associated with a clubfoot.

Treatment for foals with acquired flexural deformity of the DIP joint initially entails exercise restriction, frequent lowering of the heel, dietary restrictions, and pain control with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs such as flunixin meglumine. Weaning the foal may be advantageous. If the toe becomes excessively worn, constructing a cap over the toe with one of the commercially available hoof composites may aid in protecting the toe and dorsal aspect of the sole from bruising and may temporarily serve as a lever arm. Although elevating the heel with a wedge shoe or pad provides comfort for the foal, the deformity gradually worsens, and eventually obtaining a normal angle and shape to the hoof is difficult. Glue-on shoes should likewise be used with caution, because they tend to promote a box shape to the foot. Oxytetracycline may be used but exacerbates the back-at-the-knee conformation.

If no improvement is achieved within 1 to 2 months of conservative treatment, surgical intervention with desmotomy of the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (ALDDFT) is recommended. When surgical treatment is combined with a trimming program, hoof conformation and function will be much improved. The owner should be made aware of the potential for a blemish at the surgical site. In a group of 23 Standardbreds treated for flexural deformity of the DIP joint, 11 foals had desmotomy of the ALDDFT, of which six raced or were sound. All foals operated on by 8 months of age had a favorable outcome. None of the 12 foals that did not undergo surgery had a favorable outcome.10

Foals in which the dorsal aspect of the hoof is in front of the vertical (hoof angle >90 degrees) are candidates for deep digital flexor tenotomy, although desmotomy of the ALDDFT has been helpful in some foals when combined with farriery, oxytetracycline, and phenylbutazone therapy. With deformities of this severity, contracture of the joint capsule and surrounding soft tissues often precludes successful management for an athletic future.

Early treatment of foals with flexural deformity involving the metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal joints consists of eliminating pain through the use of analgesics, exercise restriction, and correction of any underlying nutritional problems. Any extremes in hoof angle should be corrected, and the foot should be trimmed at an angle suitable for that individual. If no improvement is achieved with conservative treatment, desmotomy of the accessory ligament of the superficial digital flexor tendon or of the ALDDFT may be helpful in select instances of moderate deformity. If the underlying cause is not addressed, the benefits of surgery will be only transient. Foals with severe deformity resulting in the limb persistently buckling forward rarely respond favorably to conservative or surgical treatment. Transection of both accessory ligaments or of the superficial digital flexor tendon may provide some improvement in horses with advanced deformity.

Treatment for acquired flexural deformity of the carpus is aimed at eliminating the underlying cause, and if the deformity is recognized early, conservative management is generally effective. The nutritional program (see Chapter 55) and growth chart for the foal should be reviewed and errors corrected if found. The nutritional program is often already balanced in some of these foals, and treatment is empirical and focused on reducing the energy intake and slowing the growth. Dietary restriction, limitation of turnout schedule and exercise, and treatment with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are currently accepted practice. Feeding of grain and other sources high in energy and protein to the mare should be restricted in an attempt to reduce the nutritional quality of the milk and to prevent the foal from ingesting grain while eating with the mare. In foals with severe deformity, limiting access to milk through muzzling the foal and stripping the mare periodically throughout the day may be attempted. However, weaning the foal from the mare to control the diet is generally easier. Acquired carpal flexural deformities may require weeks to months to correct. Splints, bandaging, and oxytetracycline may provide some benefit. These benefits are often short-lived if the underlying cause is not addressed.

Rupture of the common or lateral digital extensor tendon is often mistaken for flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal joint or carpus because the foal knuckles forward when walking. The disorder may be recognized shortly after birth or generally by 3 to 4 days of life; rarely it may occur in foals up to 3 weeks of age. Diagnosis is based on the characteristic gait of knuckling forward at the fetlock and the presence of a fluctuant swelling over the dorsolateral surface of the carpus (Figure 59-5). There is usually palpable laxity in the extensor tendons. The limb can be placed in a normal position when the foal is standing. There may be a greater tendency to rupture the extensor tendons in foals with flexural deformities, especially in those that are born prematurely.

Fig. 59-5 Rupture of the common digital extensor tendon. A, Note the fluctuant swelling over the dorsolateral surface of the left carpus. B, The fetlock buckles forward.

Treatment consists of applying a heavily padded splint over the dorsal or palmar aspect of the lower limb to prevent knuckling forward and traumatizing the dorsum of the pastern and fetlock. Dorsally placed splints are most effective if they do not slip or rotate. Casting may be used but is generally not necessary. Stall confinement is important until the foal develops the ability to use the limb. Foals generally require 1 week to 2 months of splinting and bandaging before they learn to ambulate properly. The prognosis is invariably good.