Chapter 126Lameness in the Pony

Horses under the height of 14 hands 2 inches (148 cm) at the withers generally are recognized as ponies. Despite this classification, ponies of some breeds are referred to as horses: for example, Icelandic (toelter) horses. Many native pony breeds are found throughout the world—for example, Asturian (Spain), Connemara (Ireland), Fell (England), Gerrano (Portugal), Highland (Scotland), M’Bayar (Senegal), Merens (Pyrenees), Ob (Russia), Pindos (Greece), and Welsh ponies. Several small island breeds also exist—for example, Balearic, Eriskay, Faroe Island horse, and Chincoteague ponies. The size and conformation of most pony breeds have evolved over centuries because of specific work requirements and geographical isolation. Several breeds are endangered, including the Yonaguni and Noma in Japan and Sorraia in Spain, and some have become extinct—for example, the Fen, Galloway, and Tarpan. Attempts are actively being made to prevent extinction of several breeds—for example, the Kerry bog pony in Ireland and the Taishuh in Japan. In recent times new breeds of pony have evolved, including the Welara and Pony of the Americas. Despite this, most ponies are crossbred.

Ponies have a considerable range of height, weight, and conformation and are involved in most spheres of equine work, including show jumping, eventing, dressage, driving, and general pleasure activities. Many ponies show great athletic ability, and when used for show jumping, they often jump heights similar to their own height at the withers. Ponies have a long life expectancy and can remain in athletic work well into their twenties. Although a small number of ponies are used for high-level competition work such as eventing and show jumping, most are used for general purpose work, when they may be ridden only in the summer months. General purpose ponies tend to be much less valuable than horses and are ridden predominantly by children, which may create emotional and financial conflicts for owners (parents) when deciding the appropriate treatment of a seriously injured pony. Many general purpose ponies remain at grass all year round and do not have access to a stable. Successful competition ponies often change ownership, at high prices, every 2 or 3 years as children outgrow them.

Few reports in the literature describe orthopedic conditions specifically affecting the pony. In this chapter I hope to give an overview of some of the conditions that are recognized in the pony.

Lameness Affecting the Pony

Ponies develop orthopedic problems similar to those in horses, but the overall prevalence of lameness in the pony is less than in the horse. This may be because of differences in temperament and body weight. With a relatively older population the incidence of some specific orthopedic conditions affecting older ponies may appear higher than in horses, but the prevalence is often unclear and may, for some conditions, be similar (e.g., laminitis as a result of Cushing’s disease).

Lameness Examination

Gait assessment in ponies can be challenging because they can have a higher limb speed than horses, and the larger, heavier pony breeds (e.g., Highland) often have a base-wide gait behind, which may make assessment of hindlimb lameness difficult. Several breeds also have gaits additional to walk, trot, and canter; these include the South African, Basotho pony, and Icelandic horse. For small ponies the handler may have to walk when leading a trotting pony, rather than run, to keep the limb speed to a rate at which the observer can detect low-grade lameness.

The low height of some ponies compared with most veterinary surgeons may create difficulties with assessment of the lower limb, and excessive force or torsion can easily be applied to the distal joints when a flexion test is performed.

In small ponies, care should be taken not to apply excessive pressure with hoof testers and, if the veterinary surgeon is tall, not to flex or twist the lower limb excessively in an effort to raise the foot to a convenient height to use the testers. Paradoxically, in comparison with horses many ponies have harder hoof horn, making eliciting foot pain difficult, so care always should be taken when assessing the response to hoof testers. The use of small or adjustable hoof testers is advisable for ponies.

Ponies can have a positive response to lower limb flexion tests despite being sound and performing to the owner’s expectations.

Diagnostic Analgesia

Some ponies are strong-willed, which can limit a conventional lameness evaluation using perineural or intrasynovial analgesia. Using a nose twitch or a low dose of an α2-sedative may aid this (e.g., 40 to 60 mcg of romifidine per kilogram or 0.6 to 0.9 mg of xylazine per kilogram intravenously). In some ponies the lower limbs may have thick skin and be very hairy, making accurate palpation of the structures difficult, particularly finding the site for a palmar digital nerve block. I am conscious that because of the relatively shorter limbs in ponies, local anesthetic solution may diffuse further than in the horse, and a reduced amount of local anesthetic solution is used for perineural analgesia (e.g., 1 mL of mepivacaine hydrochloride for each nerve for palmar digital or palmar [abaxial sesamoid] analgesia).

Imaging Considerations

For most clinical situations a similar number of radiographic images are required to examine the lower limb of a pony as for a horse. Although obtaining good-quality radiographs of the lower limb is generally easier, some important lesions may be more subtle than in the horse, particularly those involving the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint and navicular bone. Conversely, one should note that a substantial amount of joint degeneration can be present in some sound ponies. It is therefore important in the pony to undertake intrasynovial analgesia to confirm that any periarticular and intraarticular abnormalities are associated with joint pain.

In some ponies, particularly those kept at grass, a substantially increased thickness of skin in the distal limbs, pelvis, and thoracolumbar areas can be present and reduces skin penetration by ultrasound waves, resulting in poor ultrasonographic images. I have found that shaving the hair and hosing the area to be scanned with warm water for 15 minutes often substantially improves the quality of the image.

Ten Most Common Conditions Affecting Competition Ponies

Competition ponies appear to have a reduced prevalence of lameness in comparison with horses; however, the common conditions they develop mimic those found in competition horses. The following list contains the 10 most common lameness conditions in the ponies treated in my practice:

Limb Deformities

Mild angular limb deformities in ponies are common, but few affect performance or require medical or surgical correction. In many native breeds in the United Kingdom a small degree of carpal and fetlock valgus deviation is common. The persistence of a full-length ulna and fibula has been associated with the development of severe angular limb deformities in Shetland ponies.1 This may be a form of atavism, the inheritance of a characteristic from remote, rather than recent, ancestors.

Congenital laxity of the digital flexor tendons in the hindlimb of Shetland ponies is not uncommon and can be associated with hyperextension of the DIP joint. Treatment is similar to that in the horse.

Adactyly (absence of all or part of a normal digit) and polydactyly (duplication of all or part of a digit beyond the normal number) and other congenital musculoskeletal defects have been recorded in ponies.2

Joint Disease

Osteochondrosis

Rarely do ponies have lameness associated with osteochondritis dissecans (OCD). Histopathological evidence of osteochondrosis specifically in ponies has been reported only in the lateral trochlear ridge of the femur.3 Based on a limited number of ponies, in my opinion the most commonly affected joints are the tarsocrural and femoropatellar joints, and lesions are found at the same recognized sites as in the horse—namely, the cranial aspect of the intermediate ridge of the tibia, trochlear ridges of the talus, the medial and lateral malleoli of the tibia, and the lateral trochlear ridge of the femur. Osteochondrosis has been seen particularly in ponies bred for showing,4 perhaps because these ponies were receiving high feed intakes in an effort to improve show ring appearance.

Lameness associated with a subchondral bone cyst in the medial femoral condyle in the stifle is not uncommon in the pony.

Osteoarthritis

Ponies develop osteoarthritis (OA) in similar joints as horses. However, many ponies have mild-to-moderate joint degeneration, are clinically sound, and perform to the level of the owner’s expectation (Figure 126-1). OA in ponies tends to be primary rather than secondary to a previous intraarticular condition, such as intraarticular chip fractures, OCD, osseous cystlike lesions, or ligamentous damage.

Fig. 126-1 Lateromedial radiographic image of the metacarpophalangeal joint of a 12-year-old jumping pony. Periarticular osteophytes on the articular margins of the proximal and distal aspect of the proximal sesamoid bones reflect osteoarthritis. There is also evidence of supracondylar lysis (A) on the palmar aspect of the third metacarpal bone and villonodular (proliferative) synovitis (B) on the dorsal border. This pony had met the owners’ expectation until 5 weeks before this examination.

Scapulohumeral Joint

Shetland and Miniature Horses have a higher prevalence of OA of the scapulohumeral joint than do other equine breeds.5-7 This typically occurs in young ponies; the mean age in one survey was 5.2 years. The lameness is usually unilateral but can be bilateral and is sudden in onset and severe (grade 4 to 5 of 5) in degree. Lameness is characterized by a reduction in the cranial phase of the stride and a low arc of foot flight. Radiological abnormalities may not be present in the acute stage.5 Ultrasonography may be used to assist in the diagnosis.8 No reported treatment has resulted in successful resolution of the lameness. Some Shetland ponies have a flatter and more shallow glenoid cavity of the scapula than other equine breeds, and this may be caused by a primary joint dysplasia that could predispose Shetland ponies to OA of the scapulohumeral joint.6 In Miniature Horses scapulohumeral joint OA can be associated with an inability of the owner or veterinarian to pick up either forelimb.7 Ponies with severe bilateral OA of the scapulohumeral joint may exhibit an unusual, compensatory hindlimb gait deficit in an attempt to redistribute weight to the hindlimbs (Editors).

Carpus

When compared to horses older ponies appear to have an increased incidence of OA of the carpometacarpal joint, often referred to as carpal spavin. The radiological abnormalities found within the carpometacarpal joint are similar to those of OA of the distal tarsal joints, and periosteal new bone and enthesophyte formation on the abaxial margins of the second and fourth metacarpal bones may also be present.9

I have observed several lame ponies with restricted flexion of the carpus and radiological evidence of carpal joint degeneration, but the lameness was abolished by perineural or intrasynovial analgesia in the more distal aspect of the limb. Restricted carpal flexion without overt lameness may result in a pony being presented because of a history of tripping and concern for the safety of a child rider.

Stifle

In a retrospective study of stifle lameness, a higher incidence of OA of the femorotibial joints was noted in Highland ponies compared with the normal referral horse population at the University of Edinburgh.10 The ponies have sudden-onset, severe (grade 4 to 5 out of 5) lameness associated with damage to the menisci and collateral or cruciate ligaments. Ultrasonography and arthroscopy are useful to assess the extent of the soft tissue damage. In some of these ponies concurrent abnormalities in the articular surface of the medial femoral condyle, as described in horses, were present.11 The extent of the meniscal and ligament damage was such that treatment was generally unsuccessful. OA of the femoropatellar joint can occur in Shetland Ponies and Miniature Horses secondary to chronic lateral luxation of the patella12 (see following discussion).

Hock

OA of the distal tarsal joints (bone spavin) is a common cause of hindlimb lameness in ponies, but as in other joints, intrasynovial or perineural analgesia is advisable to confirm the relevance of any radiological changes. Icelandic horses appear to be predisposed to OA of the distal hock joints.13 An epidemiological study showed that 23% of Icelandic horses in Sweden had radiological signs of bone spavin.14 A causal relationship has been found between hindlimb lameness and radiological evidence of bone spavin and the Icelandic horses’ ages and hock angles. No relationship was found with environmental factors such as training and showing.15 The lameness found in Icelandic horses is often mild, despite moderate-to-severe radiological changes.13 OA of the talocalcaneal joint has been seen in ponies,16 and in my opinion the incidence is higher in ponies than horses. Surgical arthrodesis is the preferred treatment for functional soundness, but the prognosis is guarded.16

Other Specific Joint Conditions

Luxation of the Coxofemoral Joint

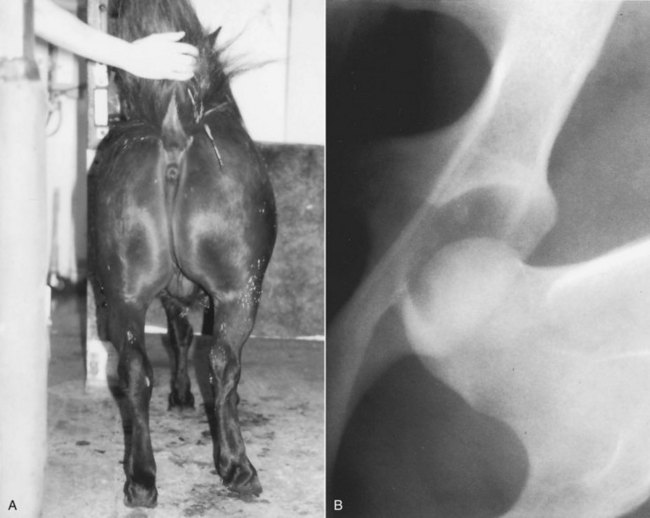

Rupture of the coxofemoral ligaments and secondary luxation of the coxofemoral (hip) joint have a higher prevalence in the pony than in the horse (Figure 126-2).17 This may be because in horses, unlike in ponies, the ilium tends to fracture before luxation of the hip occurs,18 although marginal fractures of the acetabulum have been seen with luxation.19 In the pony, ligament rupture usually occurs after trauma, and the head of the femur is often displaced in a craniodorsal direction. Affected ponies adopt a characteristic posture with outward rotation of the foot and stifle, inward rotation of the tarsus, and a pronounced shortening of the affected limb. Open or closed reduction has been used to treat the luxation, but the prognosis for long-term soundness is poor.17 Successful closed reduction has been noted in two ponies that were seen within 12 hours of the initial injury.19 Successful surgical management of a Miniature Horse with coxofemoral luxation using open reduction and a novel toggle suture, synthetic capsulorrhaphy, and trochanteric transposition has been reported.20 Ponies with unsuccessful reduction or irreducible luxation can be salvaged for breeding or companion purposes by excision arthroplasty.21 Coxofemoral luxation is often complicated by upward fixation of the patella.18,21 Ligament rupture may occur without luxation of the coxofemoral joint, and the clinical signs are similar to those of luxation except for the absence of limb shortening.18

Fig. 126-2 A, Typical appearance of luxation of the coxofemoral joint in a pony. Note the outward rotation of the stifle and foot, inward rotation of the tarsus, and shortening of the right hindlimb. B, Ventrodorsal radiographic image of the right coxofemoral joint demonstrating the caudodorsal luxation of the head of the femur.

Dysplasia of the Coxofemoral Joint

Hip dysplasia has been reported in the Norwegian Dole and a Shetland pony colt.22 In the latter, hip dysplasia was associated with the development of OA in the coxofemoral joint.

Luxation of the Patella

Lateral (sub)luxation of the patella in Shetland ponies is common.23 The condition is usually congenital but can be acquired and affects one or both hindlimbs. A distinction should be made between (sub)luxation and congenital permanent lateral luxation (see the following discussion). The cause of the condition is thought to be malformation of the trochlear ridges and groove, but rupture of the medial femoropatellar ligament has been reported in one pony.24 Postmortem examination usually reveals that (sub)luxation is associated with a broadening and flattening of the medial and lateral trochlear ridges of the femur, particularly the distal aspect of the medial trochlear ridge. Whether these changes are congenital or are caused by bone modeling is unknown. The clinical signs vary, but in most ponies the patella can be easily manipulated laterally and then replaced in the trochlear groove, and in some ponies the (sub)luxation can be observed during motion. The degree of (sub)luxation varies among ponies and can vary during an individual pony’s life. Patellar luxation can be observed in lateromedial and caudocranial radiographic images, but to confirm (sub)luxation a cranioproximal-craniodistal oblique (skyline) image of the patella is required. In ponies with (sub)luxation the patella may appear an abnormal shape on the skyline projection, but this is caused by rotation and abnormal positioning and not by bone modeling.23 Ponies with lateral luxation of the patella have been treated successfully by medial imbrication and lateral release incision12 or imbrication and recession sulcoplasty.24 Hermans and colleagues,23 using a limited breeding experiment with a group of Shetland ponies, found evidence to suggest monogenic autosomal recessive hereditary transmission of this defect.

Congenital permanent lateral luxation of the patella is also seen in Shetland ponies. Affected newborn foals are unable to extend the stifle fully and therefore have a crouched, squatting position when standing. The lateral trochlear ridge of the femur in affected foals is often flat rather than convex.23 The prognosis for successful treatment is poor.

Upward Fixation of the Patella

Intermittent upward fixation of the patella is a not uncommon condition in ponies, affecting young ponies (typically 2 to 3 years old), and older ponies secondary to an orthopedic problem in the limb. The clinical presentation is similar to that in the horse.

Hemarthrosis

A higher incidence of hemarthrosis has been noted in ponies than in horses,25 and this is often secondary to a systemic disease such as a blood clotting disorder or hepatopathy. Affected ponies have acute-onset lameness with a severely painful joint effusion(s).

Subluxation of the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint

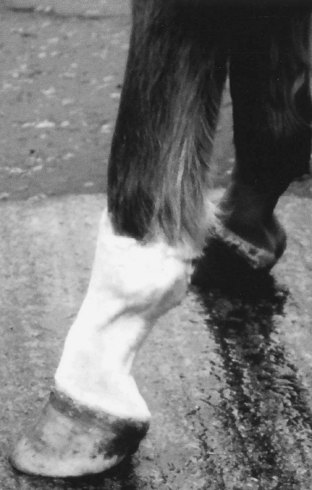

Nontraumatic dorsal subluxation of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) (pastern) joint has been recorded in the hindlimbs of ponies.26 The condition usually occurs bilaterally in young ponies (Figure 126-3). Dorsal subluxation of the PIP joint is observed when the affected limb is not bearing weight. The subluxation is reduced as weight is borne on the affected limb, and an audible clunk often accompanies joint reduction. Tenotomy of the medial head of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) in the proximal metatarsal region has produced good results in treating this condition.26 Unilateral dorsal subluxation of the PIP joint has been observed in a 3-year-old pony secondary to infectious arthritis of the tarsocrural joint.27 The subluxation resolved after successful treatment of the infectious arthritis.

Treatment of Joint Disease

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs should be used with care in lightweight ponies because they may be more susceptible to phenylbutazone toxicity.28 (Recommendations by some phenylbutazone-supplying drug companies in the United Kingdom state that the maximum level of phenylbutazone in ponies is 4.4 mg/kg orally on alternate days compared with a maximum level of 4.4 mg/kg twice daily for horses.) The ulcerogenic properties of orally administered phenylbutazone are possibly more pronounced in ponies because of less efficient gut absorption. Systemic and intraarticular corticosteroid use in ponies also has to be undertaken with caution because of the potential for development of laminitis.29

If arthroscopy or arthrotomy is undertaken in the diagnosis or treatment of joint disease, one should note before giving a prognosis that ponies appear to accommodate greater cartilage degeneration than horses.

A Fell pony foal with infectious arthritis should be checked for immunodeficiency syndrome before treatment is initiated.30

Fractures

Common fractures seen in horses (i.e., proximal phalangeal fractures, third carpal bone slab fractures, and condylar fractures of the third metacarpal or the third metatarsal bones) are rare in ponies. Most fractures are secondary to trauma. Hindlimb fractures, particularly involving the lateral splint bone (fourth metatarsal bone [MtIV]), often result from kicks from other horses.

In some ponies, closed fracture reduction and using a cast alone may result in successful bony union in fractures that would require internal fixation in a horse. The lighter weight of most ponies also means that the use of internal or external fixation of long bone fractures is more successful than in a horse. Repair of complete fractures of the humerus, tibia, and radius that would require euthanasia in a horse can be attempted in lightweight ponies (<300 kg).31 Treatment may involve using intramedullary implants such as a single Steinmann pin, stacked pin fixation, or intramedullary interlocking nails. External fixation for comminuted lower limb fractures (e.g., proximal phalanx) is also more successful in the pony.32 External fixation using a transfixation cast, with or without a U-bar,33 or an equine modified type II external skeletal device may be successful.34

Many fractures of the splint bones (second and fourth metacarpal bones, and the MtIV), including proximal fractures, heal satisfactorily with conservative management in the pony. I also have found in the pony that complete excision of the MtIV as previously described35 is successful in treating fractures of the proximal third of the MtIV; however, this occasionally leads to instability of the tarsus.

In ponies with severe or multiple fractures of the carpus, pancarpal or partial carpal arthrodesis can also be considered.36 Arthrodesis of the scapulohumeral joint of a Miniature Horse also has been described.37

It may be important when undertaking internal (or external) fixation in older ponies to assess whether the pony may be compromised systemically by Cushing’s disease, because this potentially could result in delayed fracture healing and problems with implant failure.

Stress fractures in ponies are rare but have been recorded.38

Foot-Related Problems

Ponies generally tend to have better foot conformation than do horses, and the prevalence of long-toe, low-heel foot conformation appears to be lower than in the Thoroughbred. Navicular disease does occur in ponies, but the incidence is considerably lower than in the horse.39 Intrasynovial analgesia of the DIP joint or navicular bursa should be undertaken to confirm any suspected radiological changes in the flexor surface of the navicular bone. Lesions within the DDFT and collateral ligaments of the DIP joint have been detected in ponies with the use of magnetic resonance imaging. The incidence of collateral desmitis of the DIP joint and DDFT injuries in competition ponies appears similar to that found in competition horses.40

Some degree of ossification of the cartilages of the foot (sidebone) is a common radiological finding in ponies,41 especially in native pony breeds. As in horses, this is rarely associated with lameness.

Laminitis

The incidence of laminitis in ponies is high, and this may be the result of an innate insulin insensitivity.42 Many of the affected ponies are obese, and a considerable amount of research has recently been carried out comparing human peripheral vascular disease and equine laminitis.43 The term equine metabolic syndrome has been introduced to describe laminitis in obese mature ponies.44 It has been proposed that hyperglycemia results from insulin insensitivity and causes impaired endothelial function and increased vascular tone. This may involve decreased nitric oxide production, increased release of endothelin-1, increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases, increased lipid oxidation, and increased vasoconstrictor eicosanoids. Dexamethasone suppression tests or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation tests give results within normal reference ranges for these ponies, ruling out underlying pars intermedia dysfunction.44 It is now common to screen for insulin insensitivity in ponies using a variety of factors.43 Exercise appears to improve insulin sensitivity in ponies.45

In the United Kingdom many ponies used for showing are obese and have a high incidence of equine metabolic syndrome. These ponies often have repetitive annual bouts of laminitis, particularly in the spring, and many respond quickly to acute therapy within a matter of days. Metformin (dimethylbiguanide) at a dose of 15 mg/kg bid orally has recently been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and is rapidly gaining considerable support in the United Kingdom for the treatment of equine metabolic syndrome.43 Chromium has also been used to improve insulin sensitivity in ponies.46 Trilostane, a 3-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor that acts to inhibit adrenal steroidogenesis, was found in one study to reduce the quantity of phenylbutazone therapy required in the treatment of horses with severe laminitis as a result of Cushing’s disease.47 It has also been used to assist conventional therapies for ponies with laminitis.44

If ponies with chronic laminitis do not receive corrective farriery, then many secondary complications can occur in the subsequent months, including recurrent subsolar hemorrhage, onychomycosis-induced white line disease,48 and abscess formation within the dorsal wall (Figure 126-4). Dorsal wall resection is indicated in treating some ponies with laminitis, and this can reduce the incidence of chronic problems.49 Repetitive bouts of laminitis also can lead to hoof and distal phalangeal deformation, resulting in the need for the construction of modified shoes for each foot.50 The deformation also can result in substantial gait alterations.

Fig. 126-4 Foot of a pony with chronic laminitis that has not received any corrective farriery. Note the extremely long toe and laminitic rings.

In a survey of horses and ponies with laminitis, the prognosis for horses was found to be no different than that for ponies.51 Restricted access to grass may need to be enforced to prevent laminitis in general purpose ponies that are never stabled. This can involve mowing the field, strip grazing, or muzzling the pony for part of the day. Care should be taken, however, not to undernourish ponies to prevent laminitis because of the potential development of hyperlipemia.52

The incidence of Cushing’s disease is higher in ponies than in horses,53 and the diagnosis of Cushing’s disease should always be considered in an older pony with laminitis.

Soft Tissue Injuries

Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis

Superficial digital flexor (SDF) tendonitis has a lower incidence in ponies than in horses. Tendonitis does occur in older ponies54; however, it is often associated with desmitis of the accessory ligament of the DDFT (ALDDFT).55 Tendonitis may not necessarily occur after strenuous exercise, and the site of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) damage can be in the proximal metacarpal region or within the carpal canal.56

Desmitis of the Accessory Ligament of the Deep Digital Flexor Tendon

Desmitis of the ALDDFT (inferior or distal check ligament), in both the forelimbs and hindlimbs, has a higher incidence in ponies than in horses.57-59 In an in vitro study the forelimb ALDDFT ruptured at lower forces in older horses and ponies, which suggested that an age-related degeneration occurs within the ligament.60 Because of the relatively older pony population, the prevalence of ALDDFT desmitis therefore may be similar to that in the horse. Clinically in the forelimb, desmopathy causes an acute-onset lameness and swelling in the proximal, palmar aspect of the metacarpal region. In the hindlimb a similar situation occurs, but desmopathy can also develop as either an insidious or a sudden onset of postural changes.59 Ultrasonography may show a focal area of reduced echogenicity or disruption of the entire cross-sectional area of the ligament. The damage may occur for part or the entire length of the ALDDFT. Prompt aggressive antiinflammatory therapy is required in the acute stage to prevent adhesion formation linking the ALDDFT to the SDFT around the parietal layer of the carpal (or tarsal) sheath.58,59 Treatment recommended for ponies with desmitis of the ALDDFT is similar to that recommended for SDF tendonitis in the horse.61 If extensive adhesion formation occurs in the forelimb, an acquired flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal joint may develop, which is difficult to treat.58 Ponies with hindlimb ALDDFT desmitis and postural changes have a very poor prognosis for a return to full soundness.59 I have used extracorporeal shock wave therapy in a limited number of ponies with excessive adhesion formation associated with forelimb ALDDFT desmitis. After treatment, the adhesions reduced extensively in size, but I am unsure if this altered the long-term prognosis.

Digital Flexor Tendon Sheath

Tendonitis of the DDFT within the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS) is not an uncommon injury in ponies,62,63 but primary DDF tendonitis further proximally in the metacarpal or metatarsal region is rare. It is my opinion that DDFT injuries within the DFTS are more common in the heavier cob types than in lighter ponies. Ponies with tendonitis have an acute-onset lameness with a painful DFTS effusion.63 There are two forms of injury: a focal tear within the central core area of the DDFT62 and a marginal longitudinal tear.63 Focal lesions within the core of the tendon can be detected by ultrasonography as areas of reduced echogenicity, occasionally with areas of dystrophic mineralization.64 The associated lameness is abolished by intrasynovial analgesia of the DFTS. The lameness is often slow to resolve (8 to 12 months), treatment is prolonged (often 15 months), and the rate of reinjury is high after return to normal work.62 Marginal tears of the DDFT are not always detected by ultrasonography, and tenoscopic evaluation of the DFTS is needed to determine the true extent of the damage.63 The incidence is higher in the forelimbs than in the hindlimbs, and the tears occur more commonly on the lateral margin of the tendon.63 After tenoscopic debridement or repair, the prognosis for ponies with marginal tears is considerably better than for those with focal core lesions.

Marginal tears of the SDFT and tears of the manica flexoria can also occur in ponies.63 As in ponies with marginal tears to the DDFT, they are best diagnosed and treated tenoscopically.

Secondary mild thickening of the palmar (or plantar) annular ligament (PAL or PlAL) of the DFTS may accompany tears to the DDFT, SDFT, or manica flexoria. After tenoscopy and tendon debridement, it has been found that PAL desmotomy is not always necessary for a return to full soundness in ponies with such thickening.63

Primary desmitis of the PAL is not uncommon in ponies, may be associated with tenosynovitis of the DFTS, and can cause secondary stenosis of the fetlock canal.65,66 Desmopathy of the PAL or PlAL occurs more often in ponies and cob types than horses, especially in teenage ponies, and may be in part a degenerative condition. It occurs in hindlimbs more than forelimbs and results in a convex swelling on the palmar or plantar aspect of the fetlock, with localized heat and pain on palpation.66 I have noted a higher incidence of plantar annular desmitis in ponies with chronic or repetitive laminitis. The condition may develop because of the postural and gait changes occurring with laminitis that put greater strain on the plantar structures of the fetlock joint. In such a situation, plantar annular desmitis could be described as a repetitive strain injury. Treatment initially should include antiinflammatory therapy and treatment of the laminitis. In ponies that are unresponsive to treatment or have chronic PAL desmitis, desmotomy may be required to relieve fetlock canal stenosis. Chronic enlargement of the PAL can occur without signs of lameness.65 However, ponies with lameness associated with PAL (or PlAL) desmopathy and asymptomatic enlargement of the PAL (or PlAL) of the contralateral limb may subsequently develop lameness in the second limb.

Wounds

Ponies undergoing second intention (contraction and epithelialization) wound healing are less likely to have excessive granulation tissue (proud flesh) than are horses, and wound contraction is generally faster.67 In ponies, leukocytes produce more inflammatory mediators, resulting in better local defenses, faster cellular debridement, and a faster transition to the repair phase of wound healing. They also appear to have better myofibroblast organization.68 An in vitro study has also found that horse limb fibroblasts have significantly less growth than those found in ponies.69

Other Conditions

The results of nuclear scintigraphic examinations of a limited number of athletic jumping ponies I have treated are similar to those described in horses70 (i.e., increased technetium-99m [99mTc] uptake in the proximal and distal aspects of the proximal phalanx, dorsal spinous processes, and distal hock joints). As in the study in horses, not all of these lesions were associated with lameness and may represent bone adaptation to the act of jumping. In all ponies, the results of scintigraphy should be confirmed by diagnostic analgesia.

Back Pain

Back injuries in ponies, particularly involving the sacroiliac joint, appear to have a lower prevalence than in horses.71 Ponies, however, often demonstrate abnormal behavioral problems such as bucking, secondary to hindlimb and occasionally forelimb lameness, that can be perceived by the owner as signs of primary back pain.

Muscular Disorders

Recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis (azoturia or tying up) does affect ponies, especially excitable types and ponies used for eventing. In general purpose ponies, recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis usually develops when the owner exercises an unfit pony. In one survey in the United Kingdom, ponies were the third most commonly affected group of horses affected by recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis.72 Raised blood levels of creatine kinase and aspartate transaminase confirm the diagnosis, and treatment is similar to that for the horse. Polysaccharide storage myopathy also has been reported in Welsh-cross ponies and in larger breeds of horses.73