Chapter 129Pleasure Riding Horse

Pleasure riding horses are a vital part of the equine industry, and many owners devote great amounts of time, money, and emotion to them. Although pleasure riding horses are of far less monetary value than competition horses, the overall importance to the owner should never be underestimated.

Pleasure riding horses often tend to be used seasonally and somewhat episodically. Uses include trail riding, hunting, gymkhana-type activities, showing, lesson horses (teaching horses), the pasture pet, and eating grass. Pleasure riding horses can be divided loosely into two categories: former professionals and others. The former professionals are horses that formerly were used for a specific athletic use, such as racing, but are no longer able to perform in the sport and have been demoted. The others include potential athletes that were unable to be used for the intended purpose because of lack of ability, poor conformation, or temperament, as well as horses and ponies that were bred casually as pets. The common causes of lameness in these two groups differ to some extent.

It is vital to be able to relate to the owners of pleasure riding horses, who often are inexperienced with horses, have little veterinary knowledge, but have tremendous emotional involvement with the horse and are often anxious. It is critical to first establish communication with the owner and try to relieve any anxieties. The veterinarian should explain the intended examination and treatment in straightforward, nontechnical language. Facilities for examination may be far from ideal and may complicate the examination. The veterinarian should not overinterpret a short striding gait shown by a horse trotting on an uneven paddock or a rocky driveway. The clinician should start from the basics and evaluate left-right symmetry, with the horse standing on a flat, level surface, if available, and then assess the horse moving in straight lines and circles. The veterinarian should be aware that the horse may have been living with a low-grade lameness, unrecognized by the owner, for a considerable time. If the owner is concerned about severe left forelimb lameness, the veterinarian would be prudent to avoid mentioning low-grade left hindlimb lameness observed concurrently because the lameness is probably not of material relevance and will only further worry the owner.

Interpretation of findings is in part dictated by the age and previous occupation of the horse. Many former professional horses have previous soft tissue injuries or show lameness after flexion of a variety of joints, and it is important to try to establish which is the current active disease process causing lameness. Many clinical observations reflect previous injuries and are unrelated to the current lameness.

Local analgesic techniques are useful in some situations, but the temperament of the horse, difficulties in adequate restraint, or examination facilities available may mitigate against them. Owners of pleasure riding horses may resist techniques that are invasive or potentially painful to the horse, whereas they may be fully prepared to pay large sums for advanced diagnostic techniques. The clinician should bear in mind that a twitch in the inexperienced hands of an owner may be dangerous and should consider using tranquilization (e.g., 20 mg of acepromazine) in the horse to facilitate local analgesic techniques.

In some situations an owner prefers a step-by-step diagnosis reached by assessing the response to treatment, even without a definitive diagnosis. This can provide the slow acquisition of useful information. For example, assessment of the response to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug treatment can be helpful. Lameness associated with a subsolar abscess is likely to deteriorate, whereas lameness from navicular disease or osteoarthritis (OA) of the proximal interphalangeal joint is likely to improve.

In former professional horses, OA and previous tendon and ligament injuries are common. Minor trauma to a joint in a horse with preexisting OA may result in severe, persistent lameness, whereas similar trauma to a normal joint probably would not result in chronic lameness. Commonly injured joints include the carpus, fetlock, hock, and stifle. Superficial digital flexor tendonitis, suspensory desmitis, and distal sesamoidean ligament injuries are common chronic injuries in former professional horses, but reinjury is comparatively unusual unless the horse is subjected to a sudden and substantial increase in exercise intensity; for example, a horse is ridden hard for 2 hours after 3 months of little or no exercise. Previous sites of chronic inflammation may become a long-term problem. For example, a horse may lose a shoe and then gallop about on hard ground, resulting in solar bruising. However, lameness may persist, and radiographs may reveal osteitis of the palmar processes of the distal phalanx. A horse with toed-out conformation may traumatize the medial proximal sesamoid bone, resulting in acute lameness, but radiology may only reveal preexisting abnormalities.

Many causes of lameness in pleasure riding horses relate to the lifestyle of pampered pets and the environment in which they are kept. Subsolar abscesses are common and often result in a severe lameness, creating panic for an owner, who assumes the horse must have sustained a fracture. Managing the owner is equally as important as treating the horse. Subsolar abscesses also may be sequelae to previous laminitis.

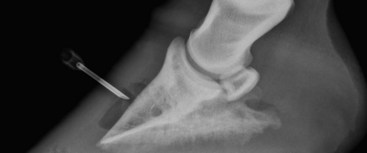

Creation of effective drainage is essential for successful management of subsolar abscesses. Without drainage, the use of systemic antimicrobial drugs is contraindicated in my experience because such drugs may prolong the course of the infection. In some pleasure riding horses with a hard hoof capsule, determining accurately the site of abscess may not be possible initially. I recommend intensive soaking with Epsom salts and warm water and poultice at night. Periodic survey radiographs can be useful. In horses with long-standing abscessation the appearance of a radiolucent defect associated with gas accumulation deep to the hoof capsule may allow direct drainage of the abscess through the hoof wall, rather than through the sole (Figure 129-1). Up to 30 days may pass before the abscess can be located accurately and drainage can be established. Once the abscess has opened or been opened, systemic antimicrobial drugs may be useful, especially if a large area of the foot is damaged.

Fig. 129-1 Lateromedial radiographic image of a foot in a pleasure riding horse with a long-standing subsolar abscess. Once a radiolucent defect is identified, a small hole can be drilled and the abscess cavity drained and medicated without opening the abscess from the sole. Lameness in this horse resolved soon after the abscess was drained.

Pleasure riding horses are at high risk for sustaining lacerations or puncture wounds, often resulting from impact with less than ideal fencing, such as barbed wire or a jagged post. Injuries vary from minor to severe, resulting in long-term lameness. Injuries may go unrecognized for several days because not all pleasure riding horses are inspected carefully and regularly. Many pleasure riding horses are kept in groups at pasture, and the introduction of a new horse can result in disruption of the hierarchy and the risk of horse-induced injury.

The veterinarian also should recognize that many pleasure riding horses have major conformational abnormalities that predispose them to the early development of OA. Many pleasure riding horses live to an old age, and age-related OA is not uncommon. Farrier care may be less than ideal and may predispose the horses to chronic foot pain and OA of the distal limb joints. Nail bind and excessive shortening of the toe are common farriery-related causes of lameness. It is important to establish the time of onset of lameness relative to when the horse was last shod. These problems are usually apparent within 48 hours. If a nail was driven inside the white line and immediately removed, this may predispose the horse to a subsolar abscess, which usually causes lameness within 7 to 10 days. If foot lameness develops more than 2 weeks after trimming and shoeing, the lameness is unlikely to be related to the farrier. Other primary foot problems include solar bruising, sheared heel, puncture injuries, and thrush. The relative incidence of these problems may be related to the ground conditions if the horse lives outside. Early, wet springs increase the incidence of thrush. Long, dry summers resulting in hard ground are associated with an increased incidence of bruising and sore feet.

Laminitis is a problem seen most commonly in two types of pleasure riding horses: obese ponies and older horses and ponies with a pituitary adenoma (pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction, equine Cushing’s disease). Laminitis is often seasonal, occurring most in the spring and early summer and also in the autumn, if a flush of grass occurs late. Navicular disease is not uncommon, and an irregular exercise history may be a predisposing factor. Navicular disease is less common in horses that have never been shod.

Cellulitis can create an acute-onset, non–weight-bearing lameness associated with pyrexia and inappetence. In some horses minor skin abrasions can be identified through which infection was initiated, but in others the primary cause may not be identified.

The incidence of tendon and ligament injuries is low and may be related to the weather and environmental conditions or to the age of the horse. Excessively deep, muddy pastures and extremely icy conditions may predispose horses to tendonitis or desmitis. Age-related degenerative changes take place in some tendons and ligaments, and in older pleasure riding horses, even those receiving no ridden exercise, sudden onset of a severe, progressive tendonitis of the forelimb superficial digital flexor tendons may develop. Progressive stretching of the hindlimb suspensory apparatus, resulting in dropping of the fetlocks, also occurs in older horses.

Neurological problems such as radial nerve paralysis may result from trauma induced by a kick from another horse in the same field or from a collision with another horse or a static object such as a gate post. In older horses, neoplastic lesions may result in secondary lameness. For example, a large melanoma in the gluteal region of a horse I examined created pressure on the sciatic nerve and thus lameness.

Pleasure riding horses are often kept at pasture in a group, with access to field shelters of variable design. Long bone fractures, the result of a kick from a companion horse, are not uncommon, especially during the winter months. Splint bone fractures are also common.

Treatment of many of these conditions is no different than in other athletic sports horses; however, certain constraints may apply that must be considered. No facilities may be available to restrict the horse’s exercise or to keep it on its own. Even if surgery is contemplated, box stall rest—mandatory after most procedures—may not be possible because there may not be a stall. Some facilities are completely inadequate for performing clean procedures, such as intraarticular medication, in a safe manner. However, owners often are prepared to spend a disproportionate amount of their income on treating a condition in their much loved horse, despite a guarded prognosis; therefore it is important to describe all available treatment options. It is also critically important to explain carefully the treatment protocol, and writing it down can be useful to ensure owner compliance. The veterinarian can create a chart that the owner should complete as medication is administered.

In managing OA, the fact that a pleasure riding horse lives outside and is constantly exercising may be of benefit. I prefer to start with the least invasive therapy first and only use alternative methods if that does not work. Some oral nutraceutical agents may be of benefit, as may be intramuscular administration of polysulfated glycosaminoglycans.

Management of wounds can be difficult because client compliance is often poor. I treat pleasure horses with wounds in anticipation of a worst-case scenario, using nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, broad-spectrum antimicrobial drugs, and confinement. Complete stall rest is often impossible, and restricted area turnout is a frequent compromise. If a penetrating injury possibly may have entered a joint or tendon sheath, I recommend referral for intensive therapy, stressing to the owner that this injury is potentially life threatening.