2 The upper limb

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

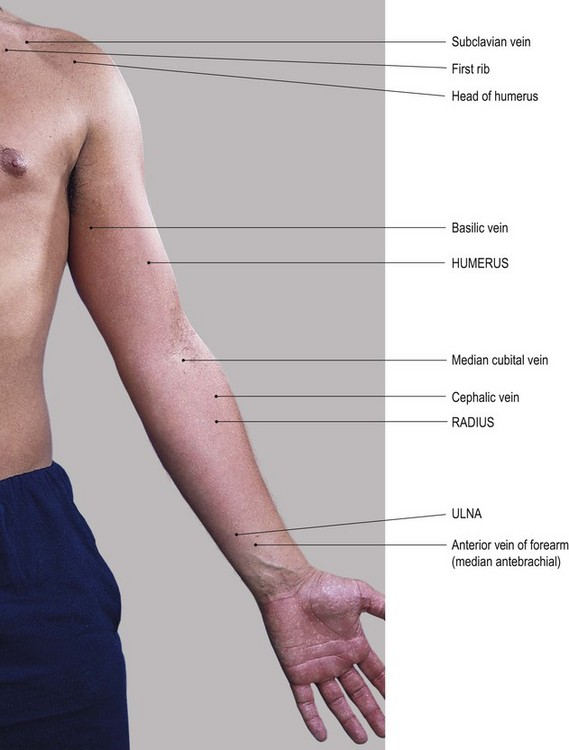

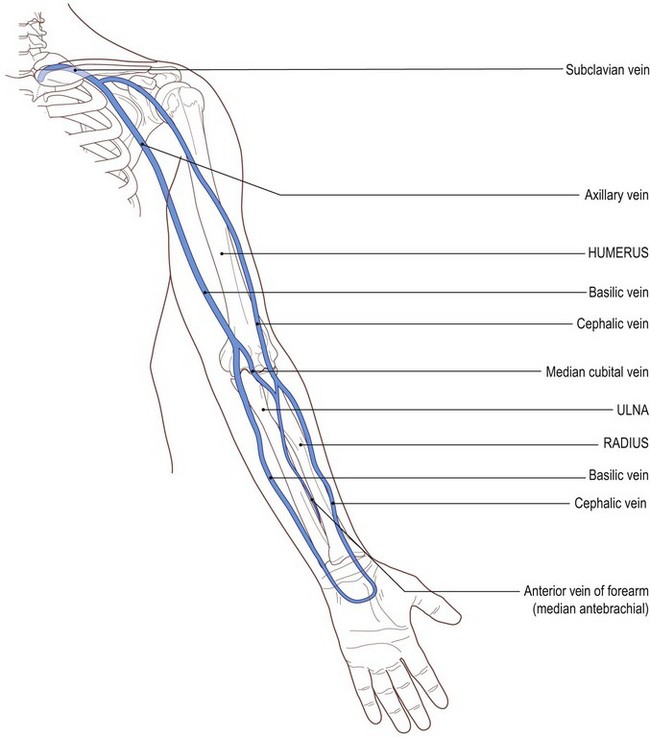

1. Find and recognize the shape and position of the clavicle, scapula, humerus, radius, ulna, carpal, and metacarpal bones and the phalanges

2. Recognize and palpate many of the bony features.

3. Name all the joints of the upper limb and understand their structure.

4. Trace the lines of the joints and where possible indicate their bony landmarks and surface markings.

5. Describe or carry out any accessory movements, possible noting the ranges in which they are most easily performed.

6. Note the ranges of each of the joints and indicate the factors limiting their movement.

7. Give the class and type of each joint, noting the axes of movement where possible.

8. Name and demonstrate the action of all the muscles palpable in the upper limb.

9. Outline the shape of the muscle on the surface and palpate its contraction.

10. Palpate tendons and attachments where possible.

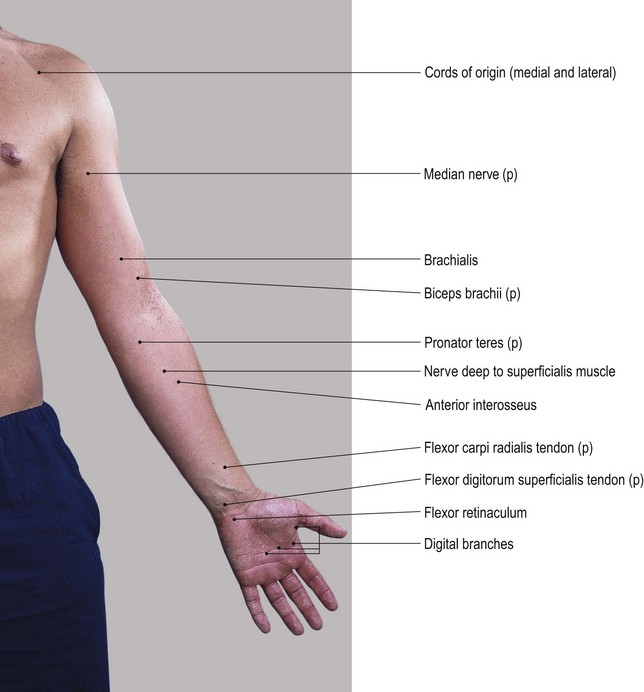

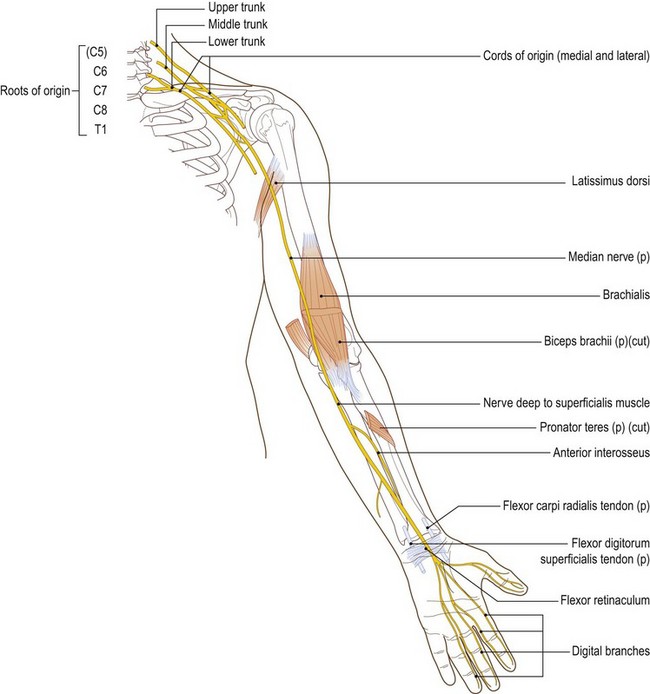

11. Name and trace all the main nerves supplying the upper limb.

12. Demonstrate the course and distribution of each of the main nerves of the upper limb.

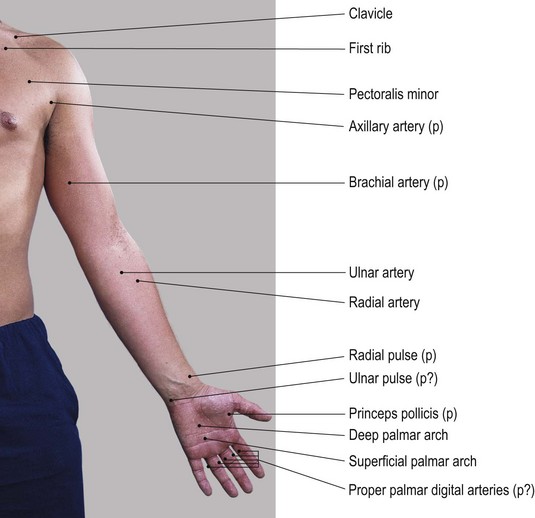

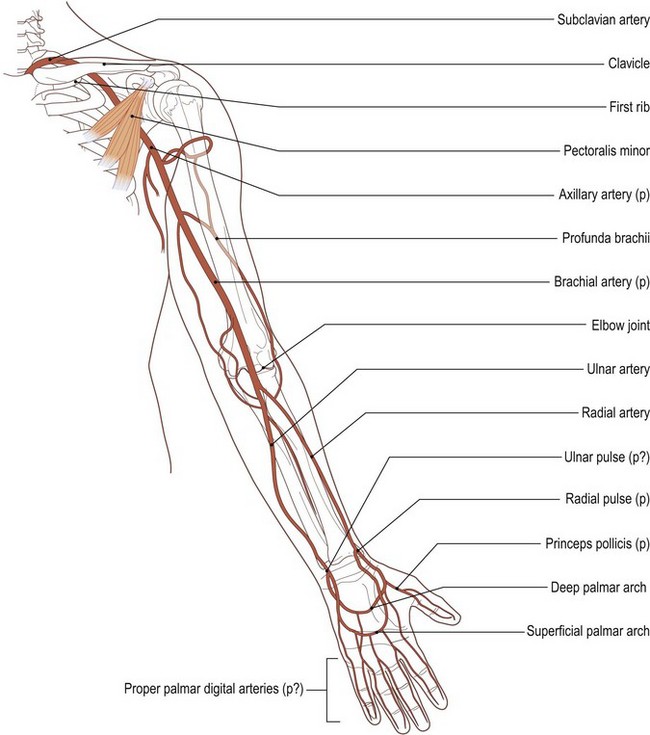

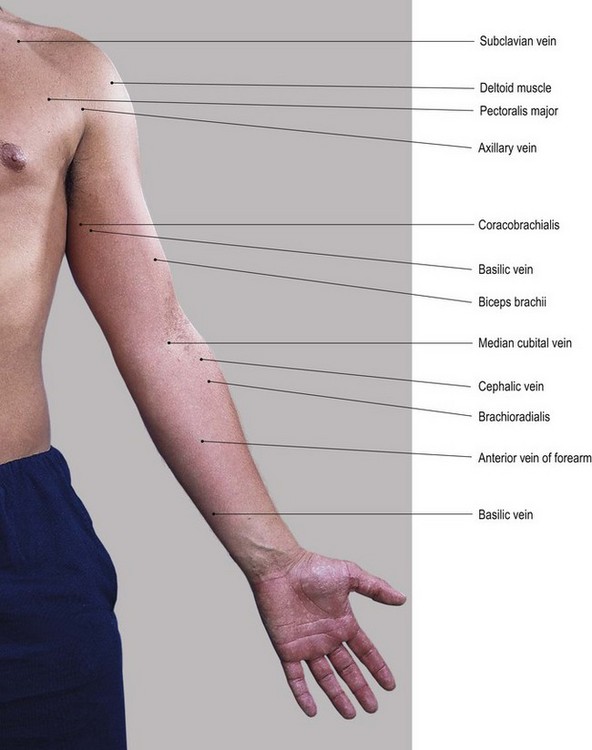

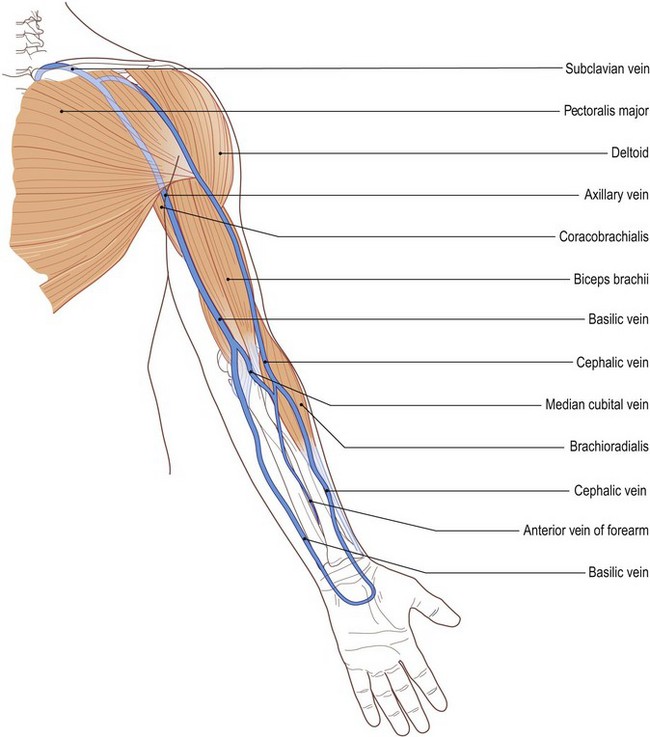

13. Name the main arteries of the upper limb, outlining their course and indicating their distribution.

14. Name the main veins of the upper limb, noting their drainage areas and course.

Bones

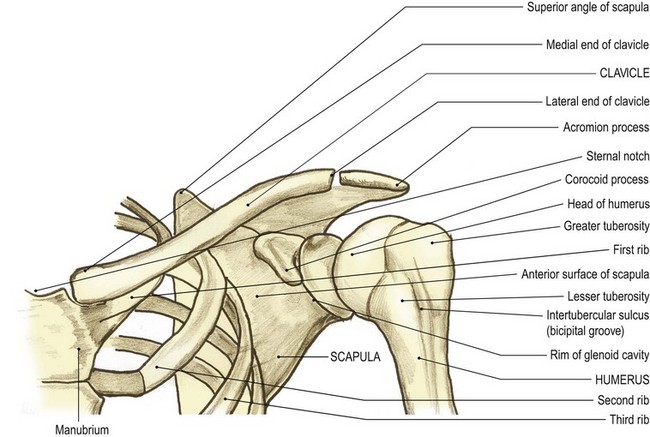

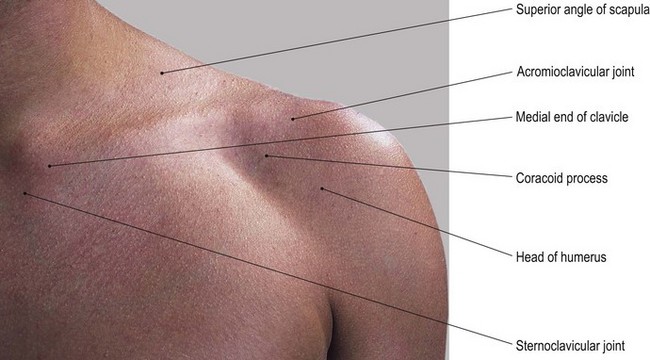

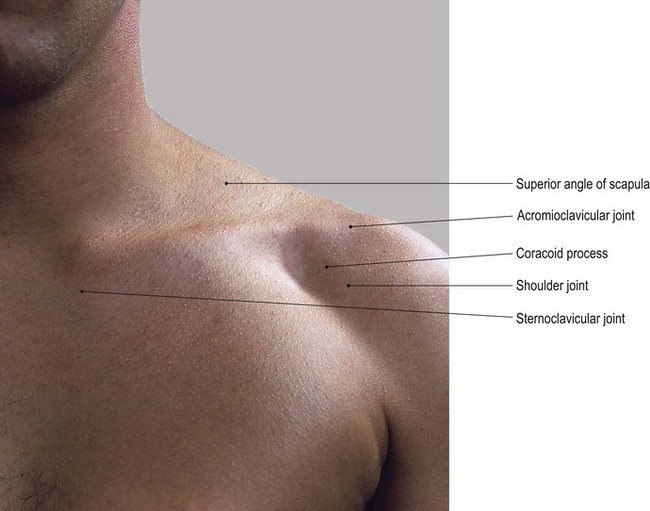

The pectoral region

The bones in this region comprise the clavicle and scapula. These bones form the pectoral girdle, with the upper end of the humerus situated vertically under its lateral margin. The clavicle is situated on the upper part of the anterolateral aspect. The scapula is situated on the upper part of the posterolateral aspect of the chest wall. The humerus is the upper bone of the arm articulating with the glenoid [glene (Gk) = a socket] cavity of the scapula at the shoulder (glenohumeral) joint.

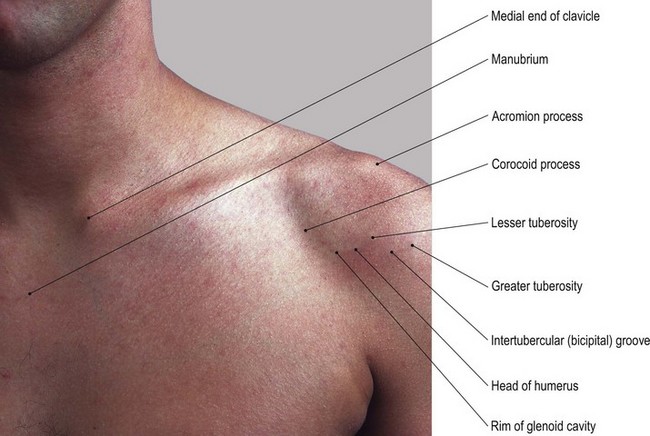

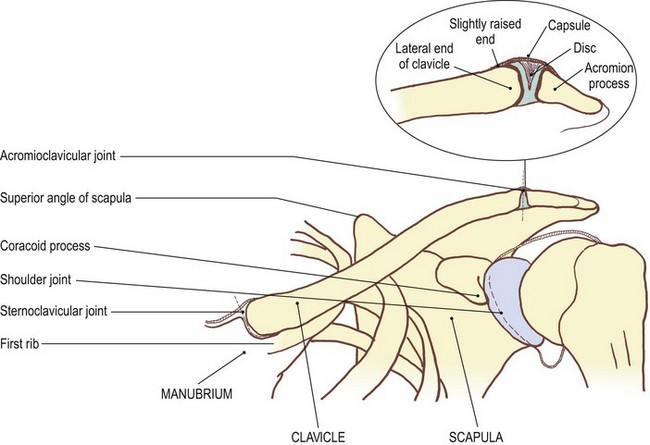

The clavicle (Fig. 2.1)

The clavicle [clavis (L) or kleis (Gk) = key; also, clavis (L) = an S-shaped bar for striking a gong] is a bone about 10 cm long and situated between the manubrium sterni medially and the acromion process of the scapula laterally (Fig. 2.1). It is a long bone and is a shallow S-shape when viewed from above. It ossifies in membrane, which means that its articular surfaces are covered with fibrocartilage and it has no medullary cavity.

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model should be in the sitting position.

• The sternal (jugular) notch. Palpate the sternal (jugular) notch which is located centrally, at the lower boundary of the front of the neck. This is formed by the superior border of the manubrium sterni inferiorly and the medial end of each clavicle on either side. Articular cartilage together with an interarticular disc and interclavicular ligament are interposed between the medial ends of the clavicles and the skin.

• The medial third of the clavicle. Move your hands laterally and you will palpate the medial third of the bone which is convex forward with a superior and anterior surface. These features are easily palpable despite giving attachment to the sternocleidomastoid muscle superiorly and pectoralis major muscle anteriorly.

• The anterior end of the first rib. Now move your hands downwards to palpate the anterior end of the first rib. It is easily identifiable where it articulates with the lateral border of the manubrium sterni.

• The middle third of the clavicle. If you move your hands further laterally, you will notice that the middle third of the clavicle begins to curve backwards, being a little more rounded in cross-section.

• The supraclavicular fossa. Posterior to the superior surface of the clavicle you will palpate a depression: the supraclavicular fossa. This fossa contains the cord-like structures of the trunks of the brachial plexus running downwards and laterally towards the upper limb.

• The upper surface of the first rib. If you now apply deep, but careful, pressure in this notch in an inferomedial direction, you will be able to palpate the upper surface of the first rib, over which the trunks of the brachial plexus pass.

• The lateral third of the clavicle. You will notice that the lateral third of the clavicle becomes flattened from above down and that its sharper anterior border is concave forward. Its subcutaneous superior surface can be easily palpated through the skin, becoming thicker at the lateral end toward the acromioclavicular joint.

• The infraclavicular fossa. Below the anterior border of the clavicle you will palpate a depression: the infraclavicular fossa. This fossa is situated between the deltoid muscle laterally and pectoralis major inferomedially.

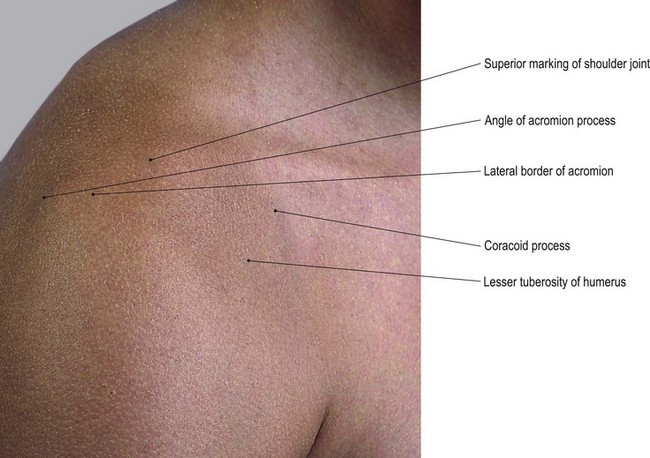

• The coracoid process of the scapula. The coracoid [korax (Gk) = a crow and oeides (Gk) = shape] process lies within the infraclavicular fossa and you can palpate its tip lying approximately 3 cm below the junction of the middle and lateral thirds of the anterior border of the clavicle and just medial to the anterior fibres of deltoid muscle.

• Note. Both anterior and posterior borders of the clavicle give attachment to muscles: deltoid anteriorly and trapezius posteriorly.

• The lateral end of the clavicle. This can be identified by a small tubercle on its superior surface which is palpable lying just medial to the acromioclavicular joint (see joints of the upper limb).

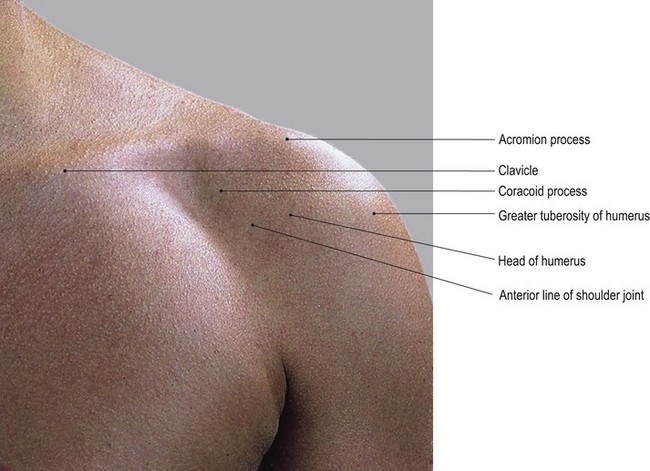

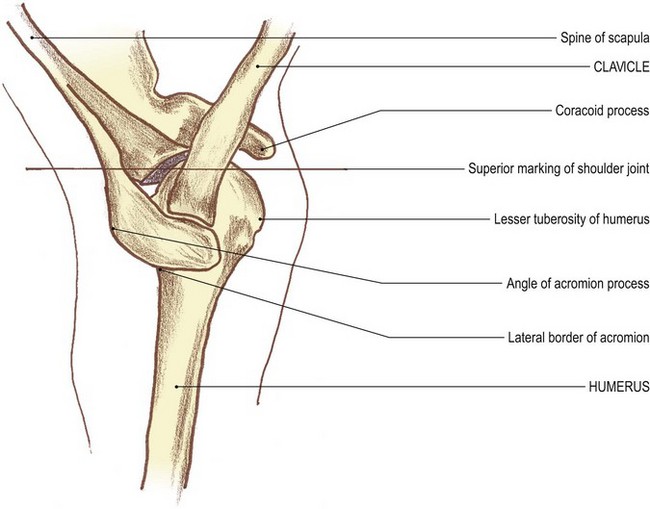

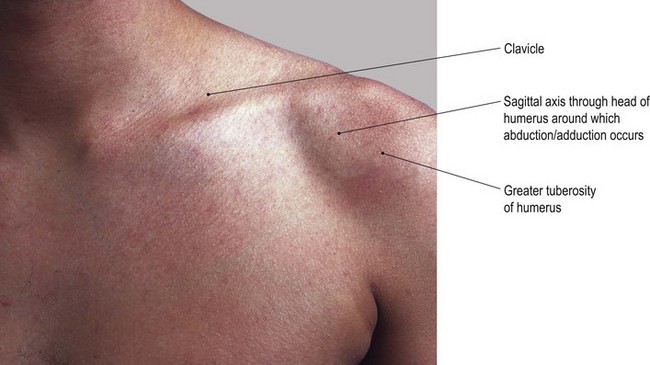

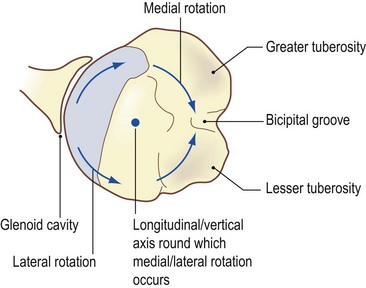

The upper end of the humerus

This comprises the head, the greater tuberosity and the lesser tuberosity.

Palpation

• The head of the humerus. On palpation, you will notice that the head is slightly more than half a sphere. It is smooth and is directed medially, slightly backwards and upwards. Its greater tuberosity lies laterally and the lesser tuberosity projects forwards with the intertubercular groove running vertically between the two tuberosities.

• The lesser tuberosity of the humerus. If you now move lateral to the coracoid process, you will palpate a slightly pointed projection. This is the lesser tuberosity of the humerus [humerus (L) = the shoulder].

• Note. This forms the medial border of the intertubercular groove, through which passes the tendon of long head of biceps.

• The intertubercular groove of the humerus. This groove can easily be palpated as it runs vertically downwards (Fig. 2.1).

• The greater tuberosity of the humerus. Lateral to the tendon of biceps, the anterior surface of the greater tuberosity may be difficult to palpate as it is covered by deltoid muscle. Place your fingers on the anterior aspect and bring your thumb in, just below and lateral to the angle of the acromion. You should now be able to grasp the greater tuberosity with your thumb and fingers between the fibres of deltoid muscle.

• Note. The greater tuberosity accounts, in part, for the rounded shape of the shoulder region.

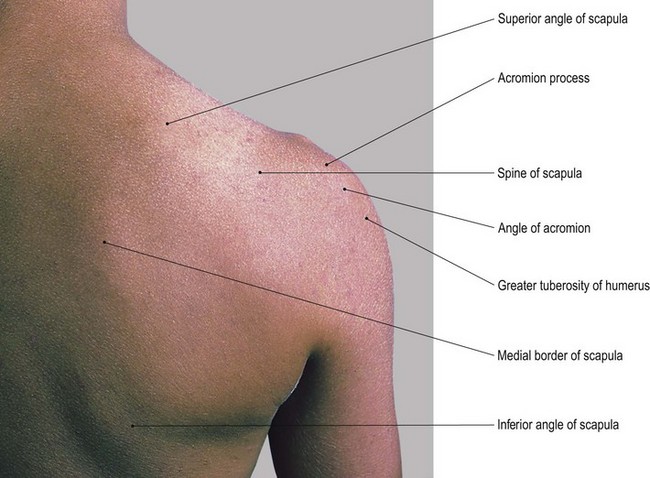

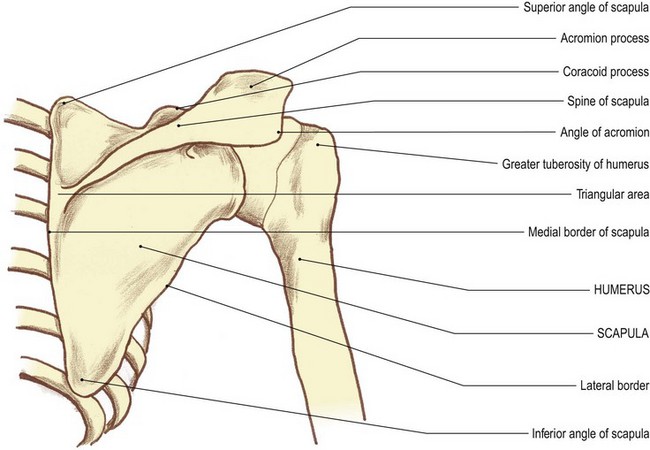

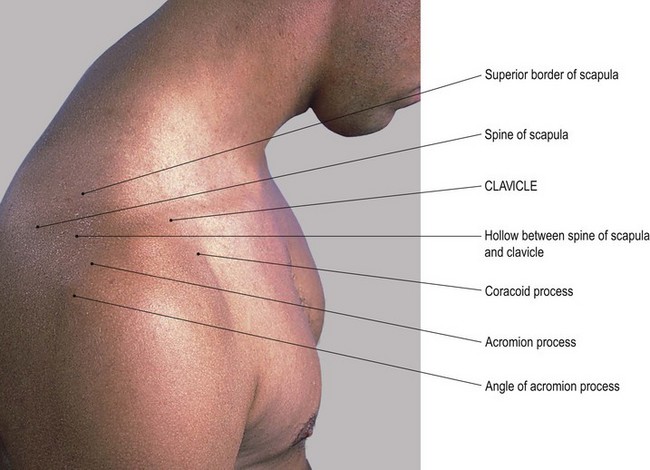

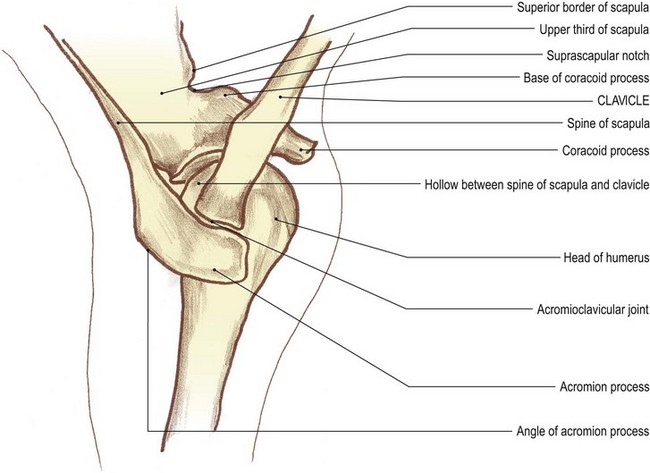

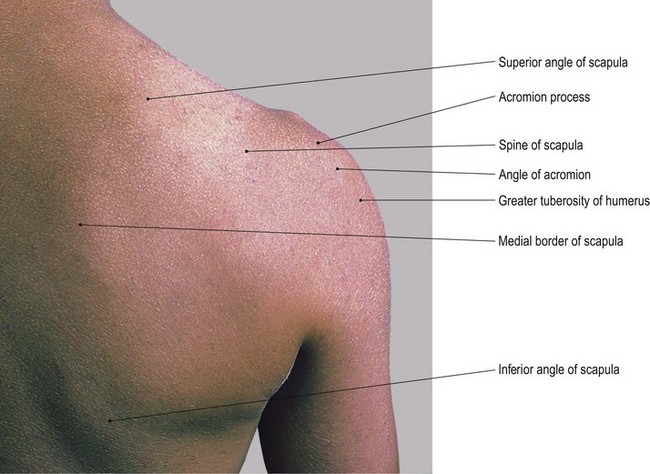

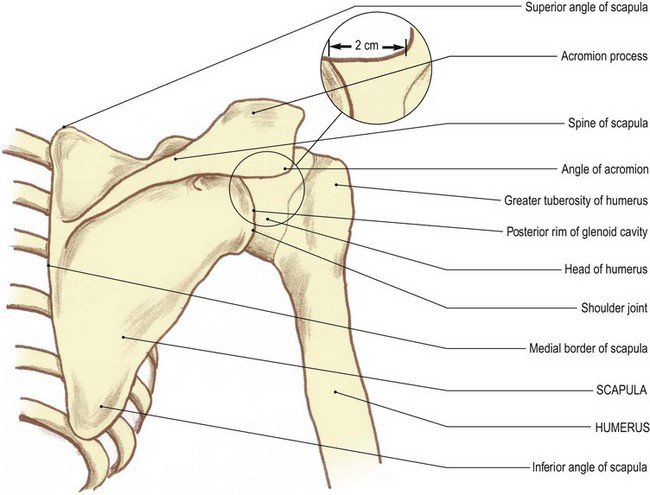

The scapula (Fig. 2.2)

The scapula [scapulae (L) = shoulder blades] (Fig. 2.2) is a flat triangular bone situated on the posterolateral aspect of the upper chest wall. It has three angles, three borders and costal and dorsal surfaces, the latter being marked by a ledge-shaped spine running almost horizontally.

The spine is wider laterally where it joins the acromion process, but narrows as it passes medially. Its upper and lower borders diverge as it meets the medial border forming a small smooth triangular area. Above the spine there is a deep hollow called the supraspinous fossa and below a larger but shallower depression called the infraspinous fossa.

The lateral angle is expanded and forms the glenoid cavity for articulation with the head of the humerus at the shoulder joint. It presents a sharp bony projection passing forward just below the lateral end of the clavicle. This is the coracoid process, which is roughened for the attachment of muscle.

Palpation

• The spine of the scapula. The whole length of the spine can be palpated between the acromion process laterally and the medial border of the scapula. You will be able to recognize its upper and lower lips even though they give attachment to the trapezius and deltoid muscles, respectively. The posterior surface is easily visible and palpable. Notice that it is narrow medially but that it gradually broadens out as it passes laterally to become the superior surface of the acromion.

• Note 1. At this point the spine is covered by a bursa (the supra-acromial bursa), enabling the skin to move easily over the bone.

• Note 2. The bone then appears to form a large quadrilateral surface, which is directed upwards and slightly backwards having posterior, lateral and short anterior borders. On its medial side, the lateral end of the clavicle and the small gap produced by the acromioclavicular joint can be palpated. The smooth triangular area at the medial end of the spine is also covered by a bursa and can be palpated through the tendinous lower fibres of trapezius muscle.

• The medial border of the scapula. The medial border of the scapula is approximately 5 cm lateral to the spines of the second to eighth thoracic vertebrae. Its full length can only be palpated with difficulty, except in lean subjects, as it gives attachment to levator scapulae above and rhomboid major and minor below, as well as being mostly covered by trapezius muscle.

• The superior angle of the scapula. This is buried in muscle and is tender on deep palpation.

• The inferior angle of the scapula. This can be identified lying on the posterolateral parts of the seventh and eighth ribs. Ask the model to raise the arm above the head. You will now be able to see and feel the inferior angle of the scapula moving laterally around the chest wall as far as the mid-axillary line.

• The lateral border of the scapula. This is very difficult to palpate as it is embedded in thick muscle (teres major and minor).

• Note. The lateral border of the scapula is by far the thickest of the borders and acts as a lever for its strong muscles to pull it laterally in scapula rotation.

• The coracoid process of the scapula. This process can be palpated where it lies anteriorly, in the infraclavicular fossa, 3 cm below the junction of the lateral and middle thirds of the clavicle. This is in spite of the fact that it gives attachment to three muscles: the short head of the biceps, coracobrachialis and pectoralis minor. Care should be taken not to apply very deep pressure as this may elicit tenderness in some subjects.

• The anterior rim of the glenoid cavity. The concave anterior rim of the glenoid cavity can be palpated just lateral to the coracoid process, running downwards and laterally for approximately 3 cm, with the head of the humerus lying on its lateral side.

Palpation on movement

Once you have been able to recognize the boundaries of the scapula by palpation of its various features, it is important to be able to follow its movements around the chest wall during activities of the shoulder girdle and upper limb.

For palpation in this area, the model should be in the standing or sitting position.

• Protrusion. Place your right hand on the point of the model’s right shoulder. Now place your left hand on the inferior angle and the lower part of the medial border of the scapula. Ask the model to pull the shoulder girdles forward as in hunching the shoulders (protrusion). You will be able to see and palpate the scapula moving forwards around the chest wall whilst remaining in its vertical position.

• Retraction. Ask the model to brace back the shoulder girdles. You will be able to see and palpate the scapula moving backwards, again not changing its vertical position.

• Elevation and depression. Keep your hands in the same position. Ask the model to raise (elevation) and lower (depression) the shoulder girdles as in shrugging. You will be able to see and palpate the scapula rising and lowering but still holding its vertical position.

• Lateral rotation. Ask the model to raise the right arm above the head. When the upper limb reaches 20°, you will be able to see and palpate the scapula rotating around an axis just below the spine nearer to its medial end. The superior angle will rise, moving medially, and the inferior angle will be observed, moving laterally and slightly upwards around the chest wall (lateral rotation). In fact, the inferior angle will reach as far as the mid-axillary line on full elevation of the humerus.

• Medial rotation. Ask the model to lower the right arm from above the head. As the arm is lowered, you will be able to see and palpate the scapula returning to its original position (medial rotation). If, however, the arm is taken behind the back, medial rotation continues and the inferior angle will come close to the spines of the vertebrae.

Anatomy

Viewed from above and slightly laterally with the upper limb in about 45° of abduction, the shoulder girdle forms a ‘V’ shape with the clavicle being the anterior and the spine of the scapula the posterior stem. They form an angle with each other of approximately 70° and are joined at the acromioclavicular joint. The greater tuberosity of the humerus is now tucked underneath the arch of the acromion. Below the junction of the middle with the lateral third of the clavicle lies the coracoid process and below the lateral third of the clavicle lies the head of the humerus. The acromion appears quadrilateral from above and continues medially and backwards as the spine of the scapula. The upper third of the scapula lies above and anterior to the spine with the superior angle being most medial and the superior border passing laterally, presenting the suprascapular notch and continuing to the base of the coracoid process.

The anterior border of the lateral third of the clavicle continues laterally with the short anterior border of the acromion process. It continues as the lateral and posterior borders, becoming the inferior border of the spine.

Palpation

• The acromion process of the scapula. [Akros (Gk) = summit and omos = shoulders]. Run your fingers from the anterior border of the clavicle across the acromioclavicular joint where the anterior border of the acromion process of the scapula continues in line for approximately 1.5 cm.

• The lateral border of the acromion process. It then passes backwards as the lateral border of the acromion for a further 5 cm.

• The inferior lip of the spine of the scapula. The border then turns medially (acromial angle) to become the inferior lip of the spine of the scapula. You will be able to palpate the whole of this area.

Palpation on movement

• Protraction. Place the fingers and thumb of your right hand on the medial end of the right clavicle. Now place the fingers and thumb of your left hand on the lateral end of the right clavicle. Ask the model to draw the shoulder girdle forward (protrusion). Palpate the lateral end of the clavicle as it moves forward, accompanied by the gliding of the scapula around the chest wall. Now palpate the medial end of the clavicle and note that it glides backwards in the clavicular notch of the sternum.

• Note. The axis around which this movement occurs is approximately 3 cm from the medial end of the clavicle, where the costoclavicular ligament attaches to the undersurface of the bone.

• Retraction. Ask the model to draw the shoulders backwards (retraction). Palpate the lateral end of the clavicle which will move backwards. Now palpate the medial end of the bone which will move forwards and become proud of the sternum.

• Elevation. Ask the model to raise the shoulder girdle (elevation). Now palpate the lateral end of the clavicle which will rise. Palpate the medial end of the bone which will move down, rolling into the clavicular notch of the sternum using the same fulcrum as above.

• Depression. Ask the model to lower the shoulder girdle. Now palpate the lateral end of the clavicle which will drop. If you palpate its medial end, you will feel this end of the bone rising to its original position. If you now ask the model to depress the shoulder girdle further, you will feel the medial end of the clavicle protruding upwards.

• Elevation of the upper limb. Ask the model to raise the arm above the head. Now palpate the clavicle as, initially, it will move as in the movement of elevation. In the final stage of the movement, however, you will be able to feel the entire bone rotating with its anterior surface moving upwards. You will also be able to palpate the lateral rotation of the scapula which accompanies this movement. If the model now lowers the arm, the shoulder girdle will return to its original position.

• Note. Movements of the clavicle, scapula and humerus and the joints between them are highly complex and should be studied in Anatomy and Human Movement (Palastanga et al 2002).

Functional anatomy

The clavicle acts as a rigid lever bracing the shoulder girdle backwards, allowing the upper limb to move freely away from the chest wall. With the powerful upper fibres of trapezius muscle raising or supporting its lateral end and the adjoining acromion process, it helps to transmit weight from the upper limb to the vertebral column via the manubrium sterni and the upper ribs. The clavicle moves around an axis close to its medial end at the attachment of the costoclavicular ligament. It is tightly bound to the coracoid process laterally by the coracoclavicular ligament.

Fractures of the bone may occur due to a fall on the shoulder, as in horse riding, motorcycling and rugby. Normally the fracture will take place where the medial two-thirds joins the lateral third, medial to the coracoclavicular ligament. The shoulder girdle may protrude forwards and a large hard swelling can be palpated and seen at the site of the fracture. Complications can occur following fractures of this bone if it is more central and the sharp bone ends are forced backwards, thus damaging the brachial plexus and/or the subclavian artery.

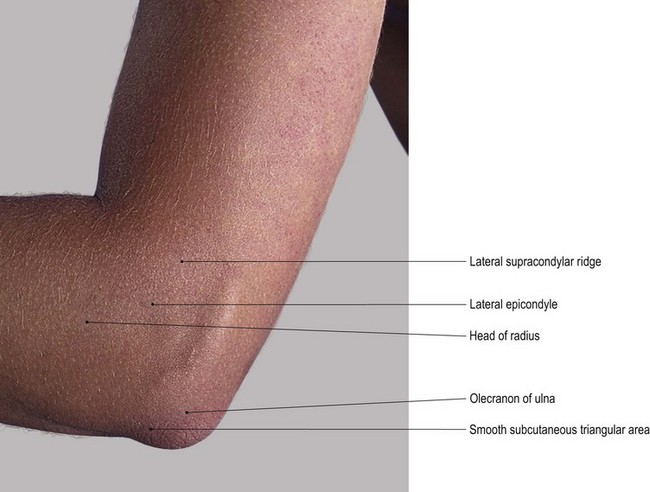

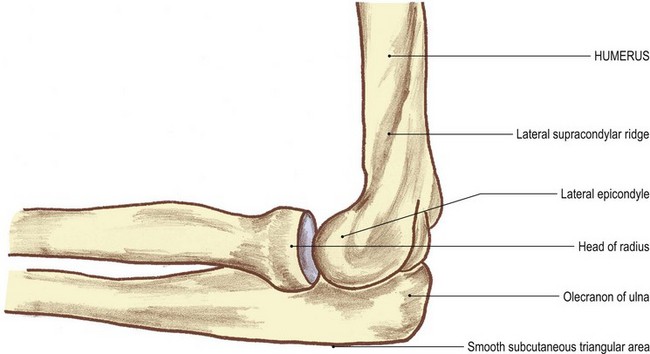

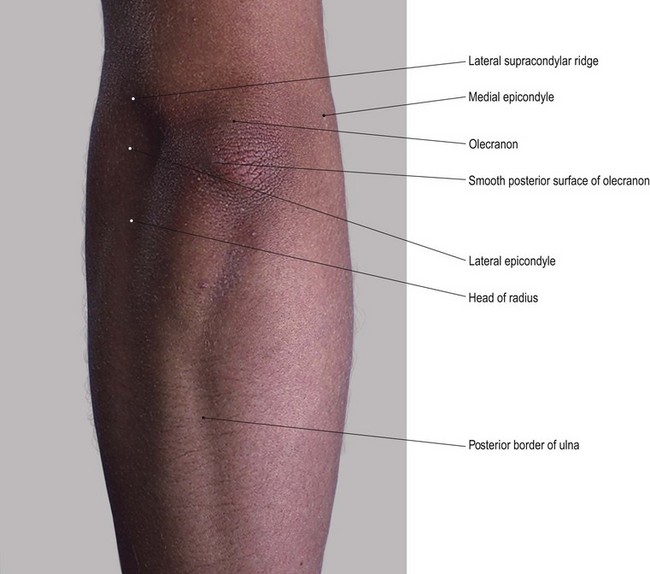

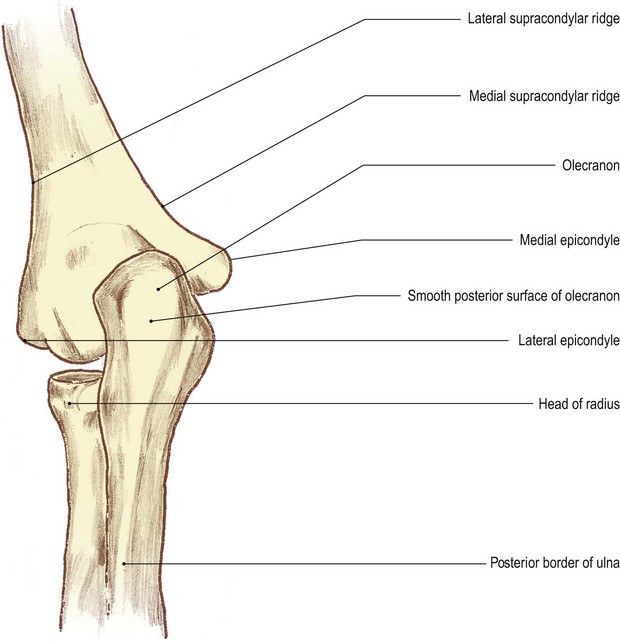

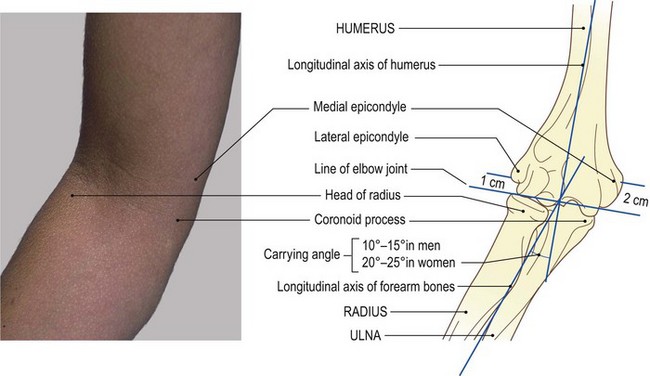

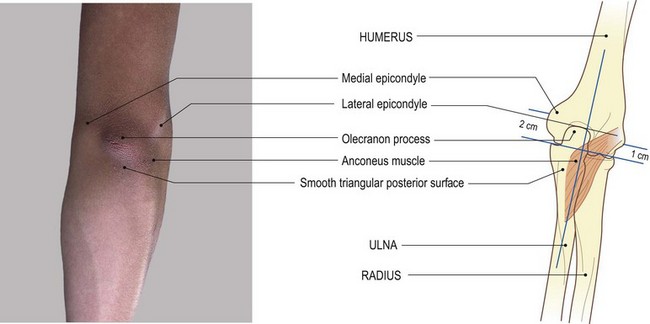

The elbow region (Fig. 2.3)

This region comprises the lower end of the humerus and the upper ends of the radius and ulna.

The lower end of the humerus is composed of a medial and lateral condyle, having two articular surfaces: the trochlea and the capitulum, respectively. Above these surfaces anteriorly are two fossae: the coronoid medially and radial laterally. Posteriorly, there is a larger depression: the olecranon fossa. On the lateral side of the lateral condyle is a prominence: the lateral epicondyle. This lies at the lower end of the lateral supracondylar ridge. The upper end of the radius is composed of a head which is button-shaped and articular on its upper surface, and the medial third of its rim. There is a neck, which is cylindrical, joining the head to the upper end of the shaft. There is also a large tuberosity (bicipital tuberosity), which projects from its medial side at the base of the neck. It is roughened on its posterior aspect for the attachment of the tendon of biceps brachii.

Palpation

For palpation in this area, the model should be in the sitting position.

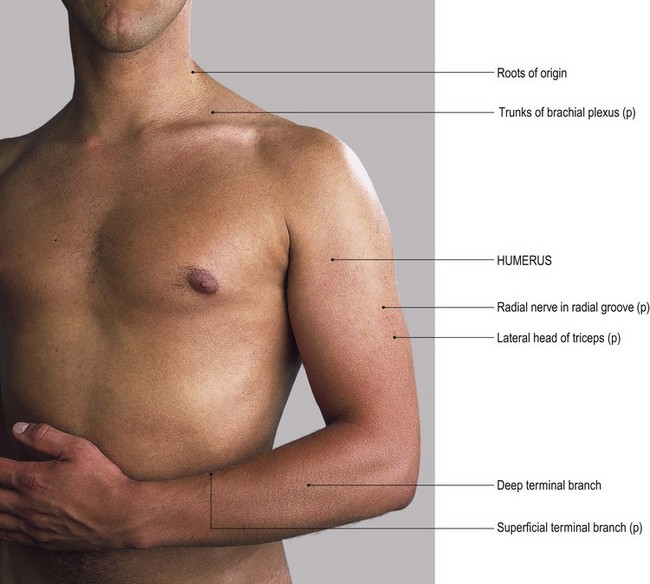

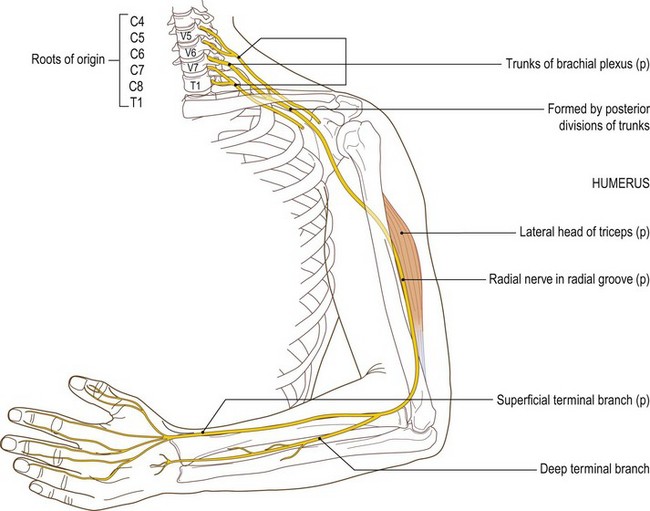

• The humerus. Find the lower attachment of deltoid muscle which is halfway down the lateral side of the arm. Just below this, you will be able to palpate the humerus.

• Note. The humerus is crossed laterally by the radial nerve running downwards and forwards. Trauma in this area can cause pain, tingling and, sometimes, numbness of the posterolateral aspect of the hand.

• The lateral supracondylar ridge of the humerus. Inferiorly, you will palpate a sharp border on the bone. This is the lateral supracondylar ridge which terminates at the large lateral epicondyle.

• The lateral epicondyle of the humerus. You will be able to palpate the posterior surface of this epicondyle which is subcutaneous.

• The olecranon fossa of the humerus. Ask the model to flex the elbow. Now you can trace the ridge medially across the back of the humerus to the commencement of the olecranon [olekranon (Gk) = the point of the elbow] fossa.

• The head of the radius [radius (L) = spoke of a wheel]. Ask the model to extend the elbow. Now you will be able to palpate the lateral side of the button-shaped head of the radius situated immediately below the humeral epicondyle. The narrow groove running horizontally between the two is the radiohumeral part of the elbow joint.

• The neck of the humerus. Palpate around the lateral half of the radial head, posteriorly, as far as the posterior aspect of the superior radioulnar joint. Just below the head, laterally, palpate the narrowed radial neck which is hidden by muscles anteriorly and posteriorly.

• The olecranon process of the ulna (Fig. 2.3a, b). Ask the model to extend and then to flex the elbow. Now palpate the large bony formation of the olecranon, particularly when the elbow is flexed. Its superior surface is more difficult to feel because it is covered by the tendon of triceps as the tendon inserts into its posterior aspect.

• The olecranon bursa. Now place your fingers on the posterior triangular surface of the olecranon. You will find that the skin and superficial fascia can easily be moved owing to the presence of the subcutaneous olecranon bursa.

• Note. If pressure is applied for some time to this area, as in leaning on the elbows, the bursa can become inflamed and swollen (bursitis).

• The medial and lateral surfaces of the olecranon process. Palpate the narrow triangular surface which has its apex downwards and is continuous with the posterior border of the ulna. Palpate this border which is subcutaneous as far as its head. Whilst you will be able to palpate the medial and lateral surfaces of the olecranon relatively easily, they are covered by muscle lower down and are more difficult to identify. The olecranon is much more difficult to palpate when the elbow is extended, as it moves into the olecranon fossa of the posterior surface of the distal end of the humerus.

Palpation on movement

• Extension. Ask the model to flex the right elbow joint to 90°. Place the fingers of your left hand on the superior surface of the olecranon, which will be at the back of the elbow. Now place the fingers of your right hand on the medial epicondyle and your thumb on the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. Ask the model to extend the elbow joint. You will be able to palpate the olecranon which will virtually disappear into the olecranon fossa on the posterior aspect of the humerus.

• Pronation and supination. Ask the model to flex the right elbow joint. Now locate the outer edge of the disc-like head of the radius. Ask the model to pronate and supinate the forearm. Note the rotation of the head of the radius beneath your fingers.

• Finally, stand in front of the model. Ask the model to flex the elbow joint fully. Take the arm in your left hand and the forearm in your right. Now ask the model to extend the elbow joint. You will observe that the forearm, which was slightly medial to the line of the humerus, now moves more to the lateral side forming an angle with the upper part of the arm. This is termed ‘the carrying angle’.

On the medial surface of the medial condyle of the humerus there is a large projection: the medial epicondyle. This is slightly hollowed posteriorly. Above this is the medial supracondylar ridge which passes up to the medial side of the shaft.

The pulley-shaped trochlea is articular and covers the anterior, inferior and posterior aspect of the bone. Its medial flange is lower than the lateral and accounts for the angle at the elbow joint.

The upper end of the ulna, lying below the trochlea of the humerus, is composed mainly of a hook-shaped process: the olecranon. There is a shelf-like process projecting forwards from the upper end of the shaft: the coronoid process. The two form a socket shape facing forwards: the trochlear notch. This articulates with the trochlea of the humerus in the elbow joint.

Palpation

• The medial supracondylar ridge of the humerus. On the medial side of the elbow, you will be able to palpate the sharp medial supracondylar ridge. Trace this ridge upwards for approximately the lower quarter of the humerus.

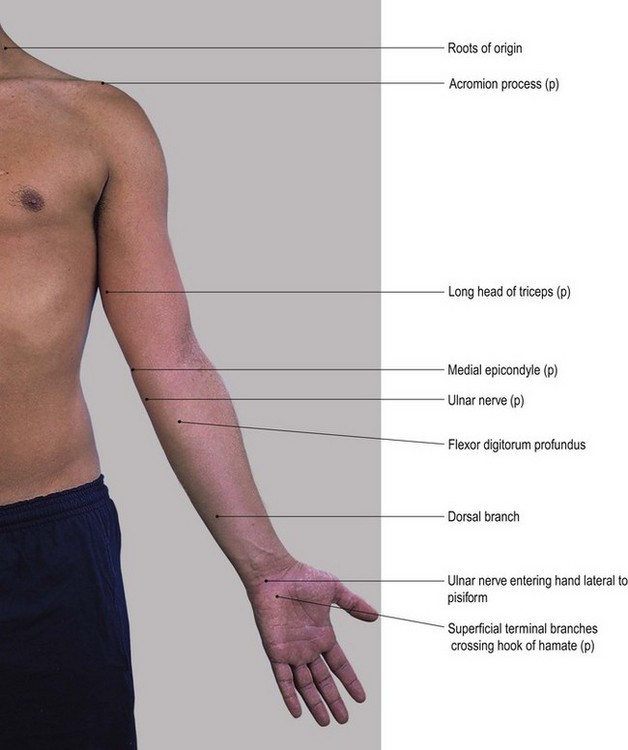

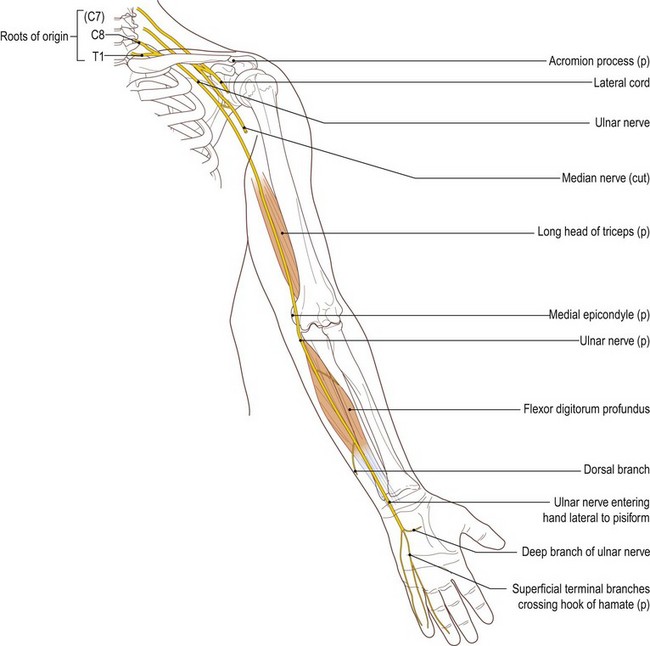

• The medial epicondyle of the humerus. At the lower end of the medial supracondylar ridge, palpate a large, bony prominence 2 cm above the elbow joint and approximately 1 cm below the level of the lateral epicondyle. This is the medial epicondyle of the humerus, behind which there is a deep groove for the ulnar nerve.

• Note. Palpation of this area may be quite tender and could cause tingling or even numbness on the medial side of the hand due to pressure on the ulnar nerve. This is often erroneously referred to as the ‘funny bone’, owing to the strange sensation when the nerve is compressed.

• The olecranon fossa. Ask the model to flex the elbow joint fully. It is just possible to feel the depression of the olecranon fossa through the tendon of triceps.

• The medial and lateral epicondyles of the humerus. From the posterior aspect, locate the medial and lateral epicondyles.

• The olecranon process of the ulna. At a point midway between the two epicondyles, press your thumb onto the back of the triceps tendon. You will observe that the tendon will sink slightly into the olecranon fossa. Just below your thumb you will palpate the bony olecranon.

• The coronoid process of the ulna (coronoid [corone (Gk) = crown; also the name given to the pointed front of a ship or plough]). Ask the model to extend the right elbow joint and and fully supinate the forearm. With the forearm in this fully extended position, examine the anterior aspect of this region. Place the flat surface of your right hand 2.5 cm below and 2.5 cm lateral to the medial epicondyle of the humerus. You will feel a hard bony projection deep to the mass of the flexor muscles. This is the coronoid process of the ulna.

Functional anatomy

• Note 1. The title ‘carrying angle’ at the elbow joint must have been given when the carrying of pails of water was common. In fact most objects carried in the hand with the elbow extended are normally accompanied by the forearm being held in the mid prone position. This eliminates the angle at the elbow.

• Note 2. When the elbow is fully flexed the hand does not oppose the shoulder joint; it is located in the mid clavicular area.

• Note 3. If the model now flexes the shoulder joint, the hand is taken first to the chin and then to the mouth, thus facilitating feeding. Keep the arm in this position. If the forearm is then fully pronated and the fingers extended, the hand now becomes a protection to the face.

Injuries and degeneration of the elbow and superior radioulnar joint often lead to loss of flexion or extension or both. This results in serious dysfunction of the upper limb, impeding its shortening and positioning of the hand. In one elbow this is perhaps acceptable, but if this dysfunction is present in both elbow complexes it may be devastating to a person’s quality of life.

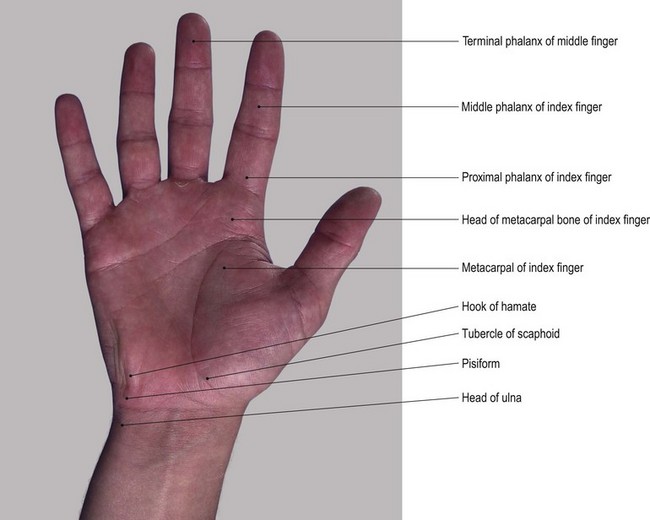

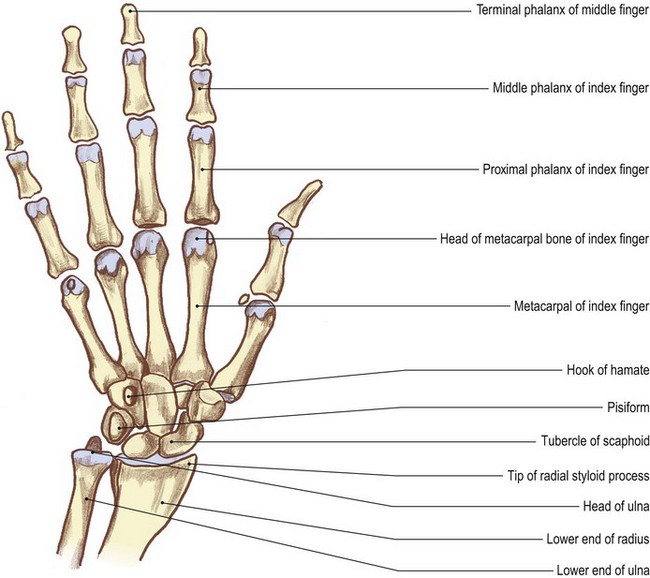

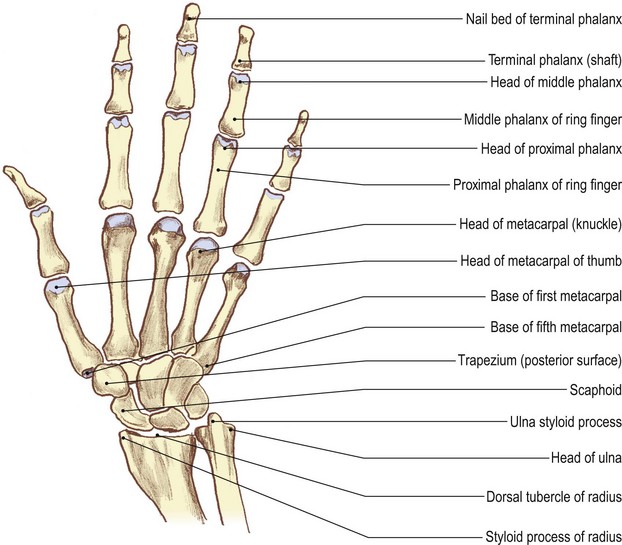

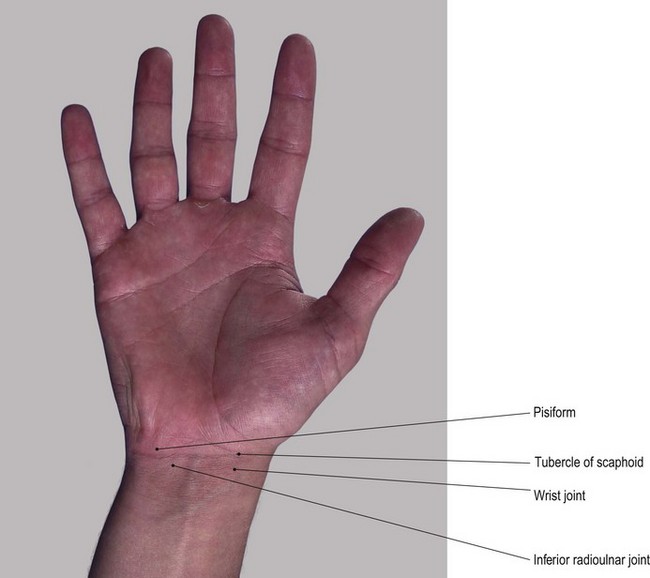

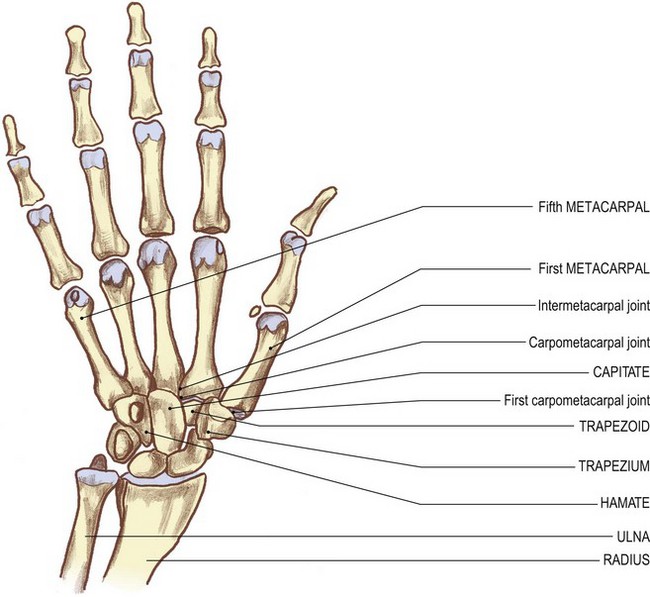

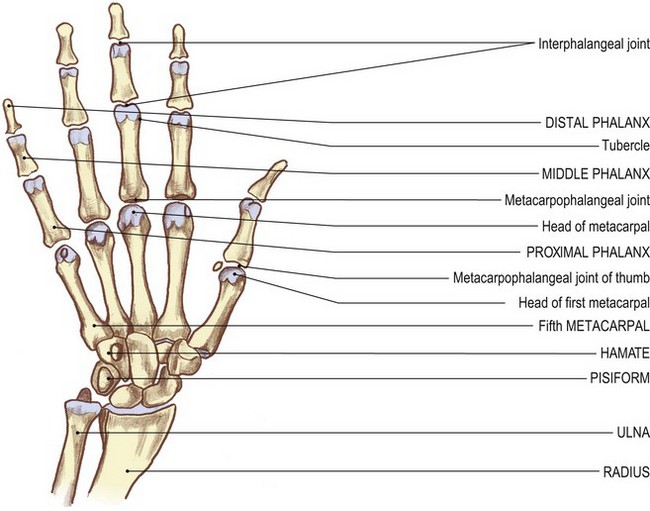

The wrist and hand

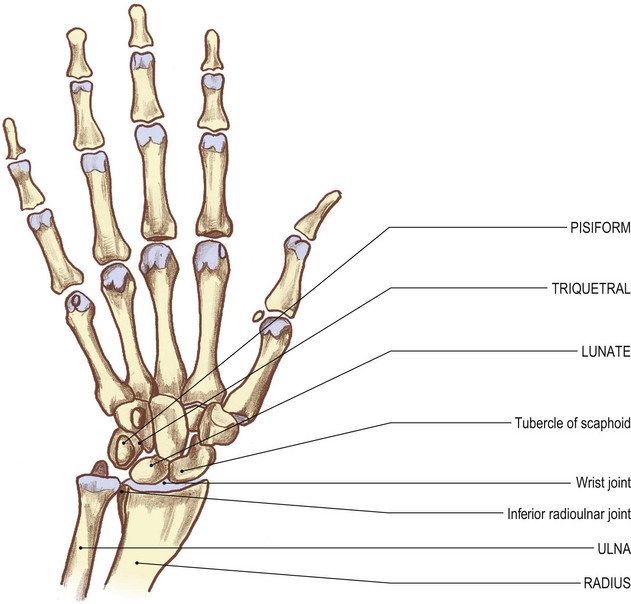

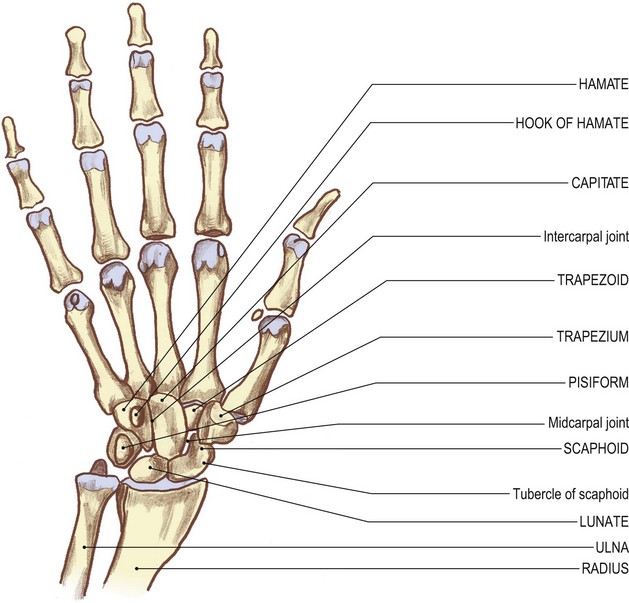

The lower ends of the radius and ulna form a shallow mortice into which three of the four bones of the proximal row of carpals – scaphoid, lunate and triquetral – fit. The fourth bone in the proximal row, the pisiform, lies anterior to the triquetral. Distally, the proximal row of carpal bones form another concavity for the reception of the second row of carpal bones: the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate [capitate (L) = head-shaped] and hamate. The capitate is the largest of the four and fits snugly into the deepest part of the concavity, being in contact with all the carpal bones except the pisiform, triquetral and trapezium (Fig. 2.4b).

The metacarpals are miniature long bones lying distal to the carpals. The metacarpal of the thumb articulates with the trapezium; the second mainly articulates with the trapezoid; that for the middle finger mainly articulates with the capitate and the fourth and fifth articulate with the hamate.

Each metacarpal head articulates with a proximal phalanx. Each finger has a middle and a distal phalanx, the thumb has only a distal phalanx.

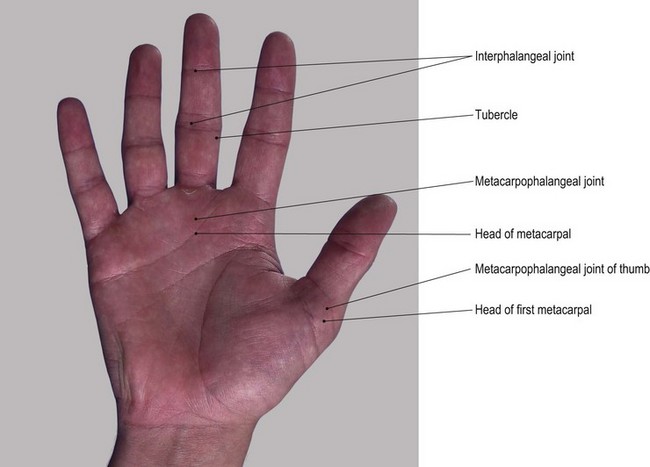

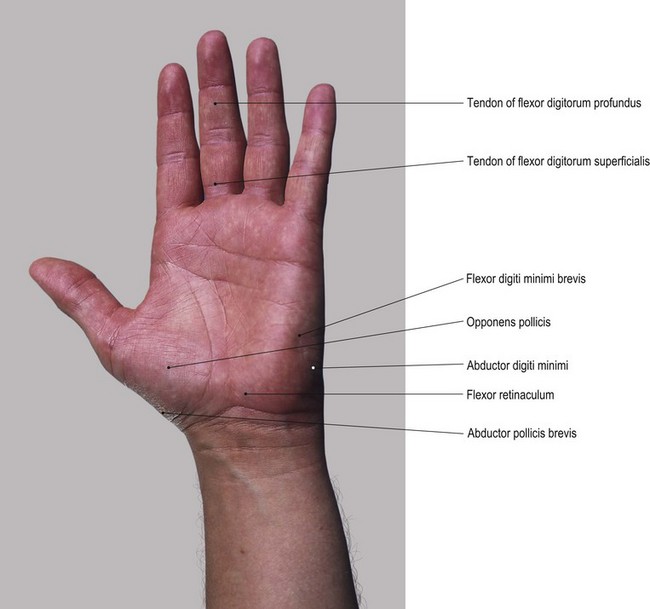

Anterior, medial and lateral aspects

Palpation

The bones of the wrist and hand are more difficult to locate on the anterior surface as they tend to be hidden by the muscles which arise and insert in the hand.

For palpation in this region, the model should be in the sitting position with the forearm resting on a pillow or an alternative support.

• The triquetral bone [triquetrus (L) = having three corners]. Return to the wrist joint. Locate the head of the ulna on its medial side (Fig. 2.4). Immediately distal to this, palpate the medial and posterior surfaces of the triquetral bone.

• The pisiform bone [pisum (L) = a pea]. On the anterior surface of the triquetral bone, palpate the pea-shaped pisiform bone. This bone is easily recognizable owing to its prominence and by the attachment of the tendon of flexor carpi ulnaris to its proximal side.

• Note. Application of deep pressure on the pisiform bone may elicit tenderness.

• The hook of the hamate bone [hamatus (L) = hooked]. If you now apply relatively deep pressure with the tip of your thumb 1 cm distal and slightly lateral to the pisiform bone, you will be able to feel a small but distinct bony prominence. This is the hook of the hamate bone. Now move your thumb from side to side and palpate two small nerves: the superficial terminal branches of the ulnar nerve. These can be compressed against the prominent hook of the hamate.

• The tip of the radial styloid process. On the lateral side of the wrist, locate the tip of the radial styloid process. It lies within a space termed the ‘anatomical snuff box’.

• The anterior border of the radius. From the styloid process, trace upwards for a short distance and palpate the sharp anterior border of the radial shaft. The radial artery lies just medial to the crest of the anterior border.

• The scaphoid bone [skaphe (Gk) = a skiff] and the trapezium [trapezion (Gk) = an irregular four-sided figure]. Distal to the styloid process of the radius, palpate the lateral surfaces of the scaphoid and trapezium bones.

• The first metacarpal bone and its proximal and distal phalanges. The first metacarpal bone is identified by a small tubercle. Its shaft leads distally to its head. You should find the base, shaft and the head of the proximal phalanx easy to palpate. The base and shaft as far as the nail of the distal phalanx [phalanx (Gk) = a band of soldiers] are equally identifiable.

• Note. The posterior surface of the bones of the thumb face laterally due to the thumb lying at right angles to the palm. Medially, the anterior surfaces are difficult to palpate due to the presence of muscle and tendon.

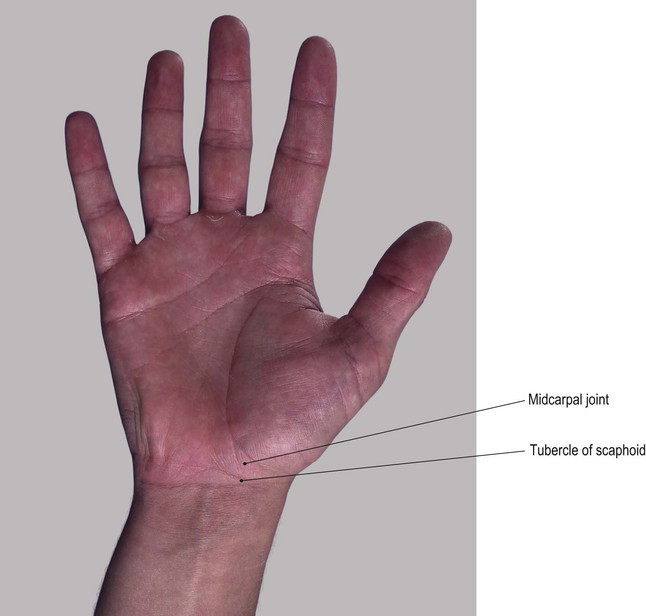

• The tubercle of the scaphoid bone. To facilitate palpation of the tubercle of the scaphoid bone, ask the model to extend the wrist. The tubercle should then be palpable at the proximal end of the thenar eminence, on the front of the carpal region, 1 cm medial to the tip of the radial styloid process.

• The vertical edge of the trapezium bone. If you apply deep pressure, the vertical ridge of the trapezium is just palpable 1 cm distal to the scaphoid tubercle.

• Note 1. This can often be a painful area for deep palpation so it is advisable to limit the number of times this technique is performed.

• Note 2. The scaphoid tubercle is prominent enough to be damaged by falls on the outstretched hand leading to a fracture. This is likely to cause pain and dysfunction of the hand for many months due to its poor blood supply leading to a long healing time.

• The second–fifth metacarpal and phalangeal bones. The anterior surfaces of these remaining bones are difficult to palpate as they lie deep to the muscle and fascia. To facilitate palpation, ask the model to extend the fingers fully. The anterior surfaces of the heads of the metacarpals can be felt in line with each finger, 2 cm proximal to the web between the fingers. Ask the model to extend/hyperextend the metacarpophalangeal joints. Now palpate the heads of each phalanx, just proximal to the creases of the interphalangeal joints. If you now grip the lateral sides of the heads between your finger and thumb, you should be able to palpate a small tubercle situated on each side.

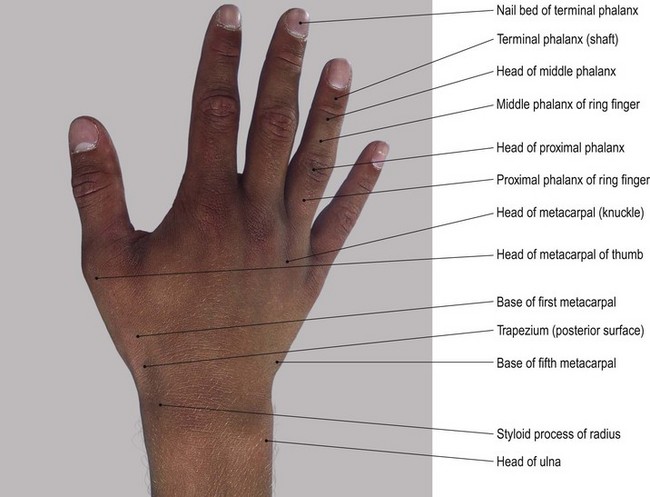

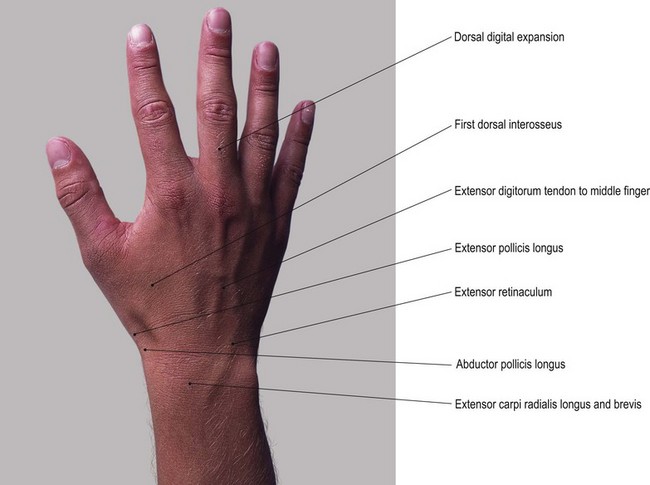

Posterior aspect (Fig. 2.5)

Palpation

• The styloid process of the ulna. Place your finger on the button-shaped head of the ulna. This is clearly palpable posteromedially, but is hidden by the tendon of flexor carpi ulnaris anteriorly. Palpate the ulna styloid process as a small projection on its posteromedial aspect, although this may be difficult as the bone is partially hidden by the tendon of extensor carpi ulnaris muscle. To facilitate palpation, ask the model to deviate the wrist radially. You will find that the head of the ulna and its styloid process become much easier to identify.

• The styloid process of the radius. Palpate the radial styloid process situated on the lateral side of the wrist, having tendons running in front and behind.

• The lateral side of the lower half of the radius. From the styloid process, trace upwards and palpate the lower half of the lateral side of the radius. From here, palpation becomes more difficult because the bone is covered by the bulk of brachioradialis muscle.

• Note. This region may be quite tender to palpate as it is often crossed by the superficial terminal branch(es) of the radial nerve.

• The dorsal tubercle of the radius. On the posterior aspect of the distal end of the radius, just above the level of the styloid process, the dorsal tubercle of the radius can be palpated. The tendon of extensor pollicis longus muscle grooves its medial side and uses it as a pulley.

• The posterior surfaces of the scaphoid, lunate [luna (L) = the moon] and triquetral bones. Find the dorsal tubercle of the radius. Below the level of this tubercle and the head of the ulna, locate a hollow; this is limited 2 cm below by the bases of the metacarpal bones. Ask the model to flex the wrist joint. Now palpate the posterior surfaces of the scaphoid, lunate and triquetral bones. They form a line distal to the tips of the radial and ulnar styloid processes.

• The trapezoid, capitate and hamate bones. Move your fingers just distal to the previous line of bones. Grip the bones between your fingers posteriorly and your thumb anteriorly. Just beyond them, palpate the trapezoid bone, which is situated at the base of the second metacarpal. Now palpate the capitate bone, situated at the base of the third metacarpal. Lastly, palpate the hamate, situated at the base of the fourth and fifth metacarpal bones.

• The second–fifth metacarpal and phalangeal bones. The lower limit of this area is marked by the bases of the metacarpal bones with their shafts running distally to end in rounded heads, all of which are easily palpable. To facilitate palpation, ask the model to flex the fingers. The base, shaft and head of each phalanx are now equally easy to palpate posteriorly. Anteriorly, they are hidden by tendons and the pulp of the fingers.

Palpation on movement

• Flexion and extension of the wrist. Ask the model to extend the wrist. Locate the tubercle of the scaphoid and the pisiform bone. Now ask the model to flex the wrist. Palpate the scaphoid and pisiform bones as they appear to move backwards and become indistinct. Keep the model’s wrist in flexion. Palpate the posterior aspect of the carpal bones just below the ulna and radius. Ask the model to extend the wrist. Palpate the posterior aspect to the carpal bones as they appear to move forwards and become indistinct.

• Flexion and extension of the fingers. Ask the model to extend the index finger. Now grip the base of the proximal phalanx with your thumb anteriorly and your fingers posteriorly. Ask the model to flex the finger. Palpate the phalanx as it moves round to the front of the head of the metacarpal leaving the head prominent (the knuckle). This is common to all the fingers, but more obvious in the index finger.

• Flexion of the interphalangeal joints. If you apply the technique as described above on the interphalangeal joints, you will palpate the head of the most proximal of the two bones as a small ‘knuckle’ shape.

• Flexion and extension of the thumb. If you now apply the same procedure as described above to the base of the proximal phalanx of the thumb, you will note that only half the movement is available and the head of the metacarpal is only partially exposed.

Functional anatomy

Fractures of the carpal bones are rare except in the case of the tubercle of the scaphoid, which is sometimes damaged by a fall on the outstretched hand.

Fractures of the metacarpal bones are fairly common at all ages and are often due again to a fall on the outstretched hand or a longitudinal force along the metacarpal, as in punching.

Injuries to the phalanges are usually due to direct violence such as trapping the fingers in a door.

Joints

Joints of the pectoral girdle

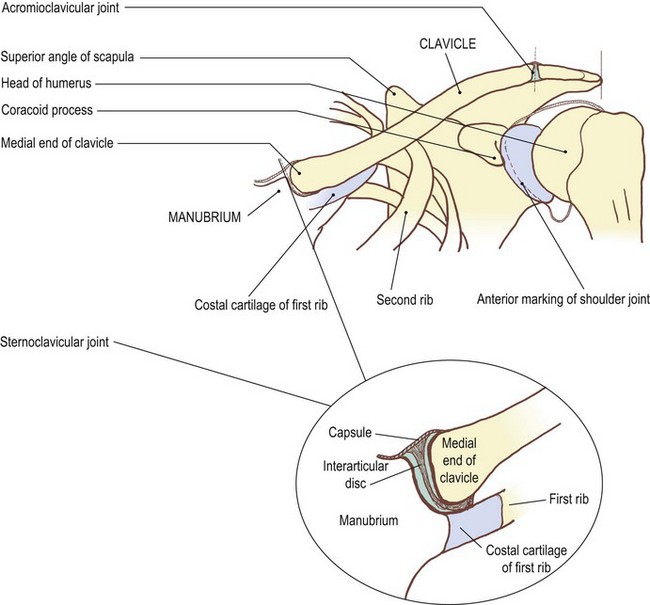

The sternoclavicular joint (Fig. 2.6)

At its medial end the clavicle articulates with the clavicular notch of the manubrium sterni. The joint is synovial, being surrounded by a capsule lined with synovial membrane, except where it is attached to the edges of a fibrous disc which divides the joint space into two separate cavities. It is a modified saddle (sellar) joint and its capsule is supported by ligaments, the intercostal above and medially, the costoclavicular laterally below the clavicle and the anterior and posterior across the front and back of the joint. It is subcutaneous, allowing easy palpation of the joint line and a reasonable examination of joint movement.

Palpation

Surface marking

For palpation in this region, the model is in the sitting position.

• The sternoclavicular joint. You can palpate this joint at the upper lateral corner of the manubrium sterni. Draw a curved line concave laterally. It is approximately 1 cm in length, extending over the lower half of the medial surface of the clavicle, passing inferolaterally for approximately 0.5 cm. Run your fingers down the front of the neck until you reach the sternal notch. Below you will feel the manubrium sterni and laterally the medial end of the clavicle with the sternoclavicular joint between the two.

Palpation on movement

• Retraction. Immediately lateral to the joint, between the clavicle and the first rib, is the costoclavicular ligament. This is not palpable, but acts as the fulcrum for movements of the clavicle at the joint. Thus when the lateral end of the clavicle is drawn backwards (retraction), the medial end can be observed gliding forward, projecting anterior to the plane of the manubrium.

• Protraction. Similarly, when the lateral end of the clavicle is brought forwards (protraction), you will be able to palpate the medial end moving backwards behind the plane of the manubrium.

• Elevation 1. Ask the model to raise the lateral end of the pectoral girdle. Palpate the medial end of the clavicle as it glides downwards on the clavicular notch of the manubrium sterni until it is level with the superior border of the manubrium sterni.

• Elevation 2. Ask the model to raise the upper limb above the head. The scapula laterally rotates around the chest wall and the lateral end of the clavicle is elevated. During the final few degrees of movement, the clavicle rotates around its long axis so that the anterior surface faces more superiorly. This rotation is due to the tension developed in the coracoclavicular ligament.

• Depression. Ask the model to pull the pectoral girdle downwards (depression). Palpate the medial end of the clavicle as it rises on the clavicular notch.

• Note. All these movements can be observed occurring around the attachment of the costoclavicular ligament.

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Gliding movements of the medial end of the clavicle. The forwards, backwards, upwards or downwards, or rotating the clavicle’s articular surfaces upwards, are all normal movements. Pressure applied to the medial end of the clavicle will produce little movement, as the stress is taken by the costoclavicular ligament which usually remains taut and reasonably inflexible.

• Movements of the medial end of the clavicle. If you apply similar pressures to the medial end of the clavicle, with the pectoral girdle in an appropriate position to aid the movement, additional movement can be achieved. Ask the model to protrude the shoulder girdle. Now apply pressure anteroposteriorly. This will augment the movement of the medial end of the clavicle. Pressure to raise the anterior surface of the medial end of the clavicle, as in the final stages of elevation, is best applied when the upper limb is as near to full elevation as possible.

The acromioclavicular joint (Fig. 2.7)

The acromioclavicular joint is immediately lateral to the anterior concavity of the lateral one-third of the clavicle, approximately 1.5 cm medial to the lateral border of the acromion process.

The acromioclavicular joint is a plane synovial joint. It lies in a paramedian plane of the body. It is surrounded by a joint capsule supported above by the superior acromioclavicular ligament. It relies for its stability, however, on the costoclavicular and the coracoclavicular ligaments which act as accessory ligaments to this joint. The two oval facets, one on the lateral end of the clavicle and the other on the medial aspect of the acromion process, are not congruent and rely on a small disc or part of a disc which fills the upper part of the joint space.

Palpation

• The angle of the acromion. Stand facing the model’s left shoulder. Run your right hand up over deltoid muscle on the lateral aspect of the shoulder. At the top you will feel the lateral border of the acromion process marked posteriorly by its angle.

• The acromial indentations. Now trace along the anterior border of the acromion for 1.5 cm. You will feel a small indentation where the clavicle joins the acromion. A very faint groove passes posteriorly to another small indentation on the posterior surface. The joint is quite difficult to palpate unless movement is occurring.

Palpation on movement

• Twisting or gapping. With careful palpation, you may be able to detect slight twisting or gapping of the acromion against the clavicle with movements of the pectoral girdle.

• Rotation. Ask the model to elevate the upper limb fully. Now palpate the acromion process as it rotates backwards against the lateral end of the clavicle. This occurs until the final few degrees of elevation when you will feel the clavicle also rotating backwards. This produces an upward movement of the anterior surface of the clavicle in its entire length.

• Note 1. This is partly due to the tension of the conoid part of the coracoclavicular ligament pulling down the posterior aspect of the clavicle, and partly due to the costoclavicular ligament at the medial end of the clavicle attaching to its posterior aspect.

• Note 2. This movement is also facilitated by the thickness of the disc in the sternoclavicular joint allowing a longitudinal rotation to occur.

• Note 3. The superior surface of the acromioclavicular joint is usually quite tender on palpation due to pressure on the superior acromioclavicular ligament. This tenderness is increased after prolonged activity involving the pectoral girdle or after carrying heavy loads on the shoulder.

Accessory movements

This joint is capable of slight gliding movements, these being forwards, backwards, upwards and downwards. It can also rotate, with one surface pivoting on the other, as well as allowing a certain amount of gapping anteriorly and posteriorly.

Palpation

• Note 1. All the above movements are normal but, as with the sternoclavicular joint, the end-range can be increased by addition of pressure in the appropriate direction.

• Note 2. The movements are best performed at the end of normal range.

• Posterior gliding of the acromion. An increase in this movement is facilitated if you ask the model to retract the shoulder girdle. Using your thumbs, now apply pressure, either to the lateral end of the clavicle or the anterior aspect of the acromion. You may find it easier to apply the former technique.

• Note 3. Although the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints may appear to be insignificant, stiffness of either will reduce the range of movement of the pectoral girdle. This may result in serious functional loss in the range of movement of the upper limb and may be misdiagnosed as shoulder joint stiffness.

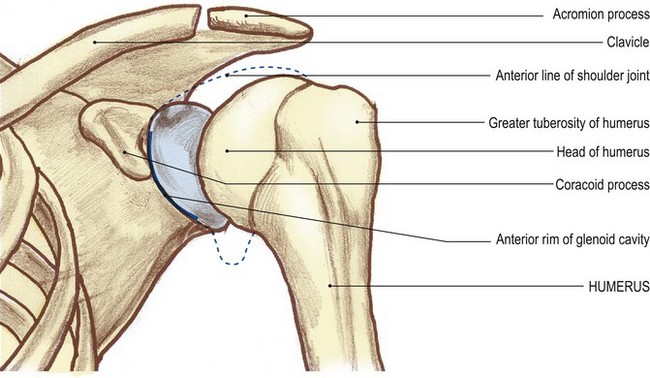

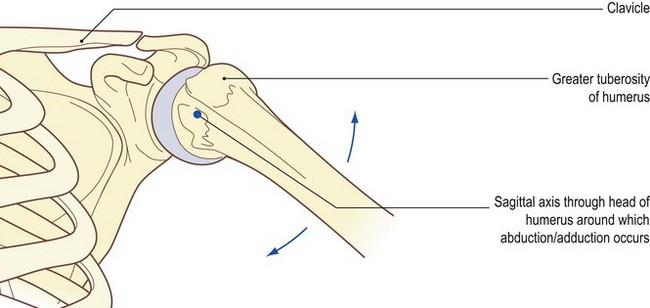

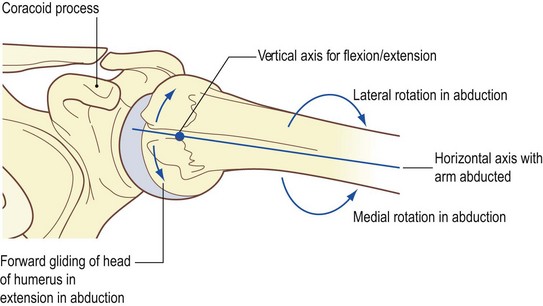

The shoulder joint (Fig. 2.8)

This is a synovial joint of the ball-and-socket type. The head of the humerus is slightly less than half a sphere, but is more ovoid in shape. The glenoid cavity is shallow and is estimated to contain only one-third the articular surface of the head of the humerus. Both surfaces are covered with articular cartilage. The joint is capable of a large range of movements which are essential for full functional activity of the upper limb. The apparent range of the joint is further increased by the movements of the shoulder (pectoral) girdle, allowing the glenoid cavity to be directed more upwards than laterally.

The joint is surrounded by a loose capsule which is lined by synovial membrane and is supported by ligaments. Anteriorly, it is supported by the glenohumeral, above and posteriorly by the coracohumeral and across the bicipital groove by the transverse ligament. A fibrous ring, triangular in cross section (the glenoidal labrum) is attached to the outer rim of the glenoid cavity, deep to the joint capsule.

Palpation

Surface marking

• The anterior joint line. This is identified by a shallow curve concave laterally. Palpate its upper boundary, which is just lateral to, and above the coracoid process. It passes downwards and slightly laterally for approximately 2–3 cm.

• The head of the humerus. Palpate the humeral head, which lies lateral to the joint line.

Palpation

The joint is deep, being surrounded by strong, thick muscles, and is therefore not easy to palpate.

For palpation in this region, the model is in the sitting position.

• The anterior part of the head of the humerus. The anterior aspect of the joint is the nearest to the surface. First, palpate the rounded anterior part of the head of the humerus. You should find this relatively easy.

• The anterior rim of the glenoid fossa of the scapula. Now carefully palpate the anterior rim of the glenoid fossa lying just medial to the humeral head.

• The head of the humerus. If you trace this bone upwards, you will feel that it is masked by the anterior part of the acromion. If you now move your fingers downwards, you will note that it becomes lost in the axilla. Laterally, you will feel that the head is bounded by the lesser tubercle of the humerus. This projects forwards and forms the medial lip of the bicipital (inter-tubercular) groove.

• The long head of biceps brachii muscle. Now palpate the long head of the biceps brachii muscle running up the groove and on to the anterolateral aspect of the humeral head.

Palpation on movement

• Lateral rotation. Ask the model to rotate the upper limb laterally. In this position, you will be able to palpate more of the humeral head.

• Medial rotation. Now ask the model to medially rotate the upper limb. You will feel the humeral head sliding backwards against the glenoid fossa and eventually disappearing.

• The lesser tubercle of the humerus. You can palpate the lesser tubercle which you will feel moving laterally and medially with the movement of rotation of the humerus.

• Abduction. Ask the model to raise the arm laterally. Now palpate the anterior part of the humeral head gliding downwards.

• Adduction. Now ask the model to lower the arm. Palpate the anterior part of the humeral head gliding upwards.

• Note 1. Palpation of the head during the movement of abduction is made more difficult by the contraction of the anterior fibres of deltoid muscle which pass across the anterior aspect of the joint.

• Note 2. Posteriorly (see Fig. 2.8e, f), the shoulder joint is estimated to be at the same level and in the same sagittal plane as it is anteriorly, being just below the spine of the scapula 2–3 cm medial to the angle of the acromion.

• Note 3. Laterally (see Fig. 2.8c, d), the centre of the joint is approximately 2 cm below the anterior half of the lateral border of the acromion.

Although the spine of the scapula, its inferior angle and medial border are easily palpable and useful for calculating the position of the shoulder joint from the back, the joint itself is set so deeply in muscle that it is impossible to recognize in normal subjects.

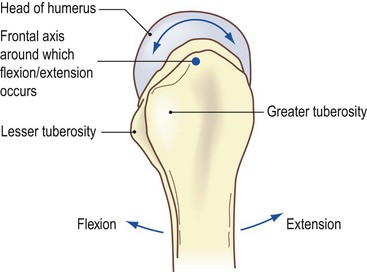

Movements of the head of the humerus

As the axis of movement of the shoulder joint is through the centre of the head of the humerus (Palastanga et al 2002), movements of the distal end of the humerus produce an opposite gliding of the head against the glenoid fossa. Thus, abduction causes a downward gliding and an upward rolling of the head of the humerus on the glenoid cavity around a sagittal axis (Fig. 2.9a, b). Flexion and extension (Fig. 2.9d), however, produce rotation or spin of the head around a frontal axis within the glenoid fossa, similar to that produced by rotating the limb in abduction (Fig. 2.9c). Rotation, with the arm by the side, however, produces a gliding forwards and rolling backwards of the head on lateral rotation and a gliding backwards and rolling forwards on medial rotation around a vertical axis. The combination of rolling in one direction and gliding in the other maintains the position of the centre of axis of the head (Fig. 2.9e). With the subject performing one movement at a time and with your fingers placed over the head of the humerus, these movements can be observed. It becomes even clearer if palpation is performed with one hand and the humerus is carefully taken through the movement passively.

The shoulder joint has a loose joint capsule and relatively weak associated ligaments. It relies to a large extent on muscular activity, especially by the ‘rotator cuff’ muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis), for joint stability. It has an extensive range of movement together with a complementary range of accessory movements.

Accessory movements

If the accessory movements are reduced, or lost, normal movement becomes reduced or occasionally eliminated.

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model should be in supine lying or in side lying. Where necessary, the arm should be supported on a pillow.

• Lateral distraction of the humeral head. For this technique to be successfully produced, the muscles of the upper limb need to be completely relaxed. The head of the humerus can now be drawn laterally away from the glenoid fossa for approximately 1–2 cm. The technique is usually possible when the humerus is between 0° and 90° of abduction. You will find it easier to palpate the movement if you ask a colleague to perform the technique. Place your fingers on the anterior aspect of the joint and palpate the head and anterior rim of the glenoid fossa.

• Gliding of the head of the humerus. Gliding of the humeral head can be in either a downwards or an upwards direction. This is achieved by pulling down or pushing up along the line of the humeral shaft. The humeral head can also glide in a forwards or backwards direction within the glenoid fossa. This is achieved by applying direct pressure on the upper end of the humerus. Again, you will find that it is easier to palpate the movement if you ask a colleague to perform the techniques as described above. Using several fingers, you should gently palpate over the area at the front of the joint where the head and glenoid fossa are identifiable.

The elbow joint (Fig. 2.10)

The elbow joint is basically a hinge joint between the humerus above and the ulna and radius below. The articular surfaces are, medially, the trochlea of the humerus above and the trochlear notch of the ulna below, and laterally the capitulum of the humerus above and the upper surface of the head of radius below.

The articular surfaces of the trochlea, capitulum, trochlear notch and the head of the radius are all covered with articular cartilage. The joint is surrounded by an extensive capsule which extends up onto the front and back of the humerus above the radial, coronoid and olecranon fossae. It is supported on either side by two strong ligaments. The ulna collateral ligament is triangular and joins the medial epicondyle to the medial side of the olecranon and coronoid processes. The lateral ligament is also triangular and joins the lateral epicondyle to the annular ligament surrounding the head of the radius. The capsule is lined with synovial membrane.

Palpation

Surface marking

• Draw a line from a point 2 cm below the tip of the medial epicondyle to a point 1 cm below the tip of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus (Fig. 2.10, b). The line passes downwards and medially due to the medial margin of the trochlea projecting down further than the lateral margin.

• Note. When viewed from the front, this produces an angle at the elbow where the long axis of the ulna deviates laterally from that of the humerus by approximately 10–15° in men and 20–25° in women (Palastanga et al 2002). The angle at the elbow is only apparent on full extension and supination of the forearm and is commonly termed the ‘carrying angle’ (Fig. 2.10b).

Palpation

• The lateral aspect of the elbow joint. You will be able to identify the joint easily on the lateral side between the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and the lateral side of the head of the radius.

• The anterior aspect of the elbow joint. Anteriorly, the joint is not palpable as it lies deep to muscles: the extensor muscles laterally and the strong flexor muscles anteromedially, with brachialis and biceps between.

• The posterior aspect of the elbow joint. Posteriorly, trace the joint line as far as the radial notch of the ulna at the posterior aspect of the superior radioulnar joint (Fig. 2.10d). Ask the model to flex the elbow joint to 90°. In this position, you can palpate the anterior edge of the olecranon which can be traced downwards on either side until it is hidden by anconeus laterally and by the medial collateral ligament medially (Fig. 2.10d).

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Rocking. Ask the model to flex the elbow joint to approximately 15°. In this position, the ulna and radius can be rocked from side to side. Stabilize the arm just above the medial and lateral supracondylar ridges with one hand and apply a side-to-side force just above the wrist. The correct angle is critical for the movement to take place which varies from individual to individual.

• Distraction. The model is lying supine or in side lying. Ensure that the muscles are relaxed. Ask the model to flex the elbow joint. Distraction is achieved by applying a considerable force in the direction of the long axis of the humerus. With the elbow at a right angle and the upper arm stabilized, you will be able to move the forearm very slightly in its long axis. This produces a gapping at the anterior and posterior aspect of the joint.

• Note. These techniques require practice and are best studied from the mobilization and manipulation literature.

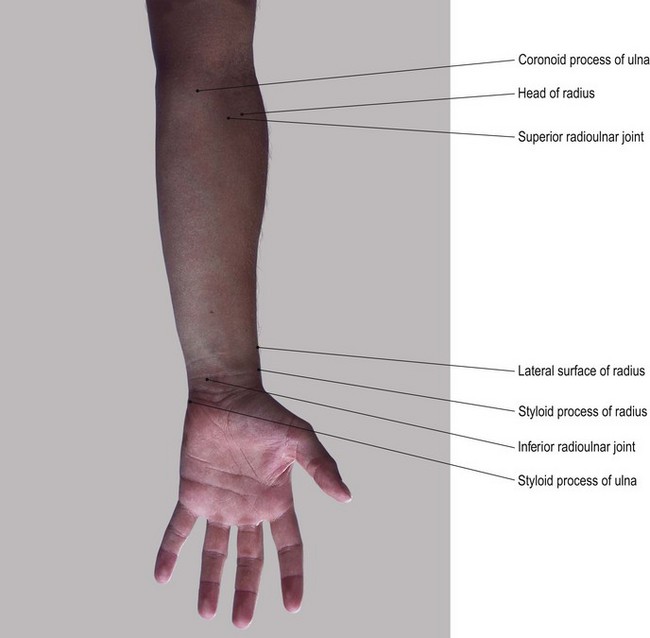

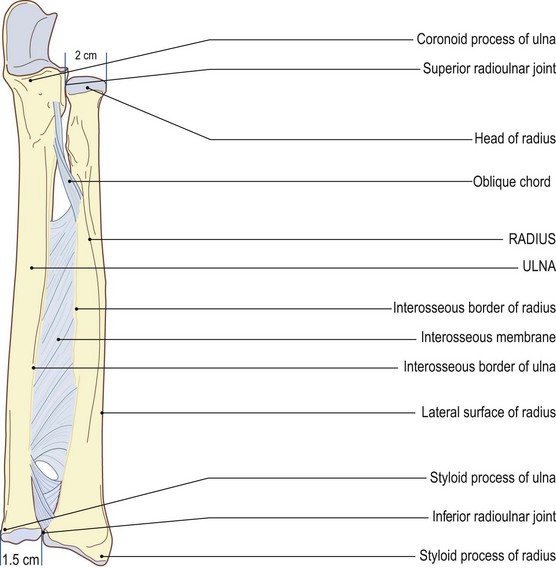

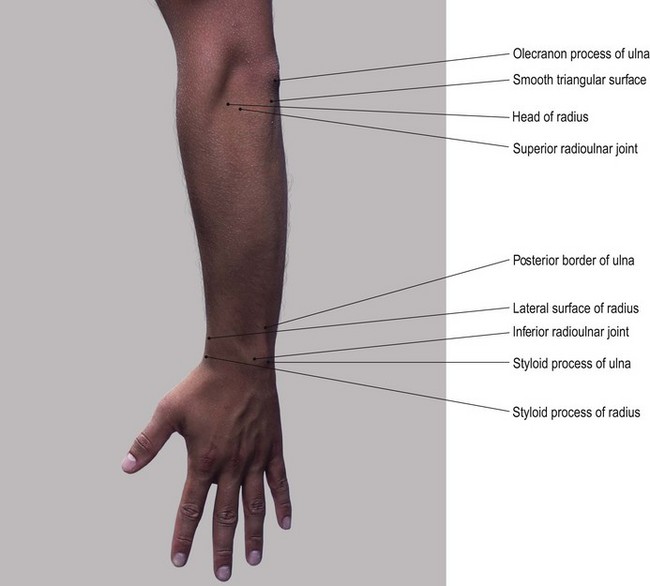

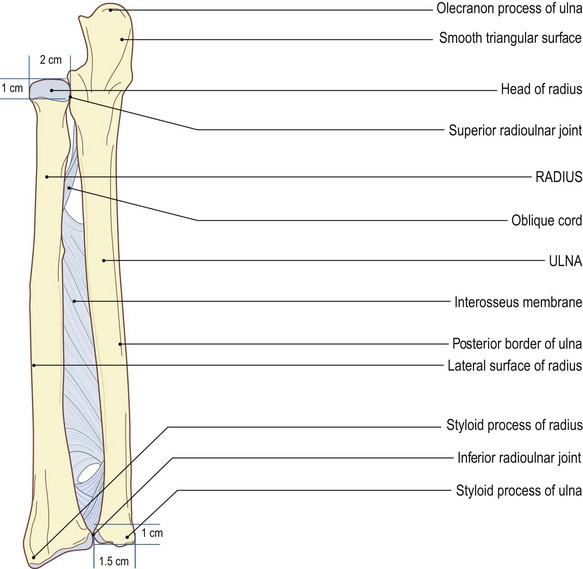

The radioulnar union

The movements of pronation and supination occur between the radius and ulna. They involve a type of rotation movement at the superior and inferior radioulnar joint and a twisting movement between the shafts of both bones. This is often referred to as the radioulnar union because the two bones are held together by the interosseous membrane.

The superior radioulnar joint

The superior radioulnar joint is a synovial pivot joint between the medial one-fifth of the head of the radius and the radial notch on the lateral side of the coronoid process of the ulna.

Both surfaces are covered with articular cartilage and are reciprocally curved. The head is surrounded by the annular ligament. This is attached in front and behind the radial notch of the ulna and forms the other four-fifths of the ring and is lined with fibrocartilage. The annular ligament is supported from above by the capsule and the triangular radiocollateral ligament of the elbow joint and from below by the quadrate ligament attaching it to the ulna. The joint is further stabilized by the interosseous membrane which binds the radius and ulna together. Synovial membrane lines the inner surface of the annular ligament in a double fold attaching to the edges of the articular facets of ulna and radius. It emerges just below the annular ligament as a loose fold. It is continuous with that of the elbow joint, although functionally it is a completely separate joint.

Palpation

Surface marking

• The superior radioulnar joint. Anteriorly and posteriorly, draw a vertical line 1 cm long downwards from the line of the elbow joint (see above), 2 cm medial to the lateral edge of the head of the radius (Fig. 2.11).

Palpation on movement

• Pronation and supination. Locate the head of the radius just below the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. Trace backwards around the radial head until the movement is arrested by contact with the lateral side of the ulna. The joint space is usually hidden by anconeus muscle. Anteriorly, the surface marking is covered by muscle and is not palpable. When the forearm is pronated and supinated, you will be able to feel the head of the radius rotating under your fingers.

Accessory movements

• Gliding of the radial head. The model is in the sitting position. Grip the head of the radius firmly between your fingers and thumb of one hand. Stabilize the upper end of the ulna with your other hand. You will now be able to produce slight backwards and forwards gliding of the head.

• Upwards and downwards gliding of the radial head. If you apply traction on the lower part of the radius, you will produce a slight gliding up and down of the head of the radius against the radial notch of the ulna.

• Note. If you apply too much traction to the radius in younger children (as in lifting the child by the forearm) the head of the radius may dislocate out of the annular ring, causing much pain and discomfort.

The inferior radioulnar joint

This joint is also a synovial pivot joint, being between the ulnar notch on the medial side of the distal end of the radius and the lateral rim of the head of the ulna. Both surfaces are covered with articular cartilage and the joint is surrounded by a capsule which is thicker in front and behind. A triangular interarticular disc is situated between the lower end of the ulna and the carpus. This attaches medially to the base of the styloid process of ulna and laterally to the medial edge of the inferior surface of the radius. At this joint, the radius moves around the head of the ulna in conjunction with the rotation of the head of the radius against the ulna at the superior radioulnar joint.

The mid radioulnar union

The radius and the ulna are joined together for most of their length by the interosseous membrane. This attaches to the interosseous borders of both bones, except for a small space at the upper part. This thin collagenous sheet, broader at its middle, is made up of fibres which pass downwards and medially from the radius to the ulna. Its fibres help to bind the two bones together whilst allowing movement between them. It gives support to the superior and inferior radioulnar joints. Due to the direction of its fibres, it transmits weight from the radius to the ulna.

Palpation

• Specific features of the radius and ulna. Examine both the radius and the ulna. Note that the lower end of the radius is large and takes any force transmitted from the carpus. In contrast, note that the radial head is relatively small and obviously transmits very little, if any, force to the capitulum. Note that, compared with the lower end of the radius, the ulna has a very small head at its lower end. This takes very little force from the carpus. Note also that its upper end is large and obviously transmits most of the force through to the trochlea of the humerus.

There is an oblique cord running downwards and laterally which attaches the tubercles at the upper part of the ulna with the radius just below its tuberosity. It is distinct from the interosseous membrane.

The interosseous membrane and oblique cord cannot be palpated.

Palpation

Surface marking

Palpation

• The posterior aspect of the inferior radioulnar joint. You will find it easier to palpate the joint line posteriorly where there is a vertical depression for 1 cm immediately above the line of the wrist joint 1.5 cm lateral to the ulnar styloid process (Fig. 2.11). Here, the tendon of extensor digiti minimi crosses the posterior aspect of the joint. Ask the model to extend the little finger and identify the tendon.

• The anterior aspect of the inferior radioulnar joint. Anteriorly the joint is much more difficult to palpate. In order to do so, slip your fingers under the thick tendon of flexor carpi ulnaris from the medial side.

• Pronation and supination. Ask the model to pronate and supinate the forearm. Now feel the radius moving around the lateral side of the head of the ulna. Note that the ulna also moves slightly laterally on pronation and medially on supination.

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Forwards and backwards gliding of the head of the ulna. Grip the head of the ulna firmly between your fingers and thumb of one hand. Now stabilize the lower end of the radius with the other hand. Now glide the lower end of the ulna forwards and backwards.

• Pronation and supination. Ask the model to flex the elbow joint. Hold the model’s forearm in your hand. Ask the model to pronate and supinate the forearm. In pronation, note the radius as it rotates around the head of the ulna. At the same time the lower end of the ulna moves slightly laterally. In supination the reverse occurs. Loss of this movement will limit the range.

• Lateral movement of the head of the ulna. Ask the model to pronate the forearm fully. Now apply pressure to the anteromedial aspect of the head of the ulna with your thumbs.

• Medial movement of the head of the ulna. Ask the model to supinate the forearm fully. Now apply pressure with your thumbs to the posterolateral side of the head of the ulna.

• Note. Both these manoeuvres achieve slight movement of the head of the ulna.

The wrist (radiocarpal) joint (Fig. 2.12)

The wrist joint is formed, superiorly, by the inferior surface of the lower end of the radius and an interarticular disc. Inferiorly, it is formed by the proximal surfaces of the scaphoid, lunate and triquetral bones. These, together with the ulnar and radial styloid processes, form a synovial ellipsoid joint. All joint surfaces are covered with articular cartilage. The joint is surrounded by a capsule, lined with synovial membrane. It is supported by the palmar and dorsal radiocarpal, ulnocarpal, radial and ulnar collateral ligaments. The interarticular disc lies between the inferior surface of the head of the ulna and the triquetral bone.

Palpation

Surface marking

• The wrist joint. Draw a line between the tips of the ulnar and radial styloid processes, slightly concave distally. The line becomes increasingly curved as it approaches the styloid processes (Fig. 2.12).

Palpation

For palpation in this area, the model is in the sitting position with the forearm resting on a support.

The joint is covered both anteriorly and posteriorly by tendons running from the forearm into the hand. There are, however, areas, mainly on the medial side, where the joint space of the wrist can be palpated.

• The posteromedial aspect of the wrist joint. Locate the ulnar styloid process on the posteromedial side of the wrist. Trace along both the medial and posterior edges of the head of the ulna. Medially, you will notice a gap just distal to this area. This contains the interarticular disc, the inferior surface of which takes part in the wrist joint articulation.

• The lateral aspect of the wrist joint. Press your fingers between the extensor tendons. Now trace the joint line just distal to the dorsal tubercle of the radius across the back of the wrist as far as the head of the ulna.

• Note. The joint line cannot be palpated anteriorly. You can draw its line horizontally just proximal to the tubercle of the scaphoid.

• The anterior aspect of the wrist joint. Ask the model to flex the wrist slightly. This will facilitate identification of the joint line. Identify the anterior line of the joint by tracing the crease across the anterior aspect of the wrist between the flattened lower end of the forearm and the elevations of the thenar and hypothenar eminences.

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Movements of the carpus. Ask the model to pronate the forearm. Now grip the dorsum of the lower end of the radius and ulna with one hand and the carpal bones with the other, so that the radial sides of your index fingers and thumbs are nearly touching. You can now move the carpus forwards and backwards, from side to side and even rotate it slightly.

• Note. Take care not to flex the wrist joint. The technique is to glide one surface on the other in a transverse plane. It will be difficult to prevent some movement occurring between the bones of the midcarpal joint.

• Distraction. Ask the model to pronate the forearm. Adopt the same hand hold as described above. Draw your two hands apart, taking care to grip the bones tightly. Do not allow too much slide of the skin and fascia.

• Note. Accessory movement at the wrist, if performed correctly, is quite dramatic, producing considerable movement in unusual directions. It must be remembered, however, that some of this movement occurs at the intercarpal and carpometacarpal joints.

• Movement of the carpal bones. With practice, it is possible to move each of the carpal bones individually on each other or on the lower end of the radius and disc. Grip one bone between your finger and thumb of one hand, while stabilizing its neighbour as described above. Alternatively, use the finger and thumb of your other hand. Slight gliding movement between the two bones can be achieved.

The hand

The intercarpal joints (Fig. 2.13)

These are all synovial, plane joints. Their surfaces are covered with articular cartilage and their capsules are lined with synovial membrane. With the exception of the pisotriquetral joint, the capsule is supported by the palmar and dorsal ligaments and radial and ulnar collateral carpal ligaments. There are also some interosseous ligaments between the proximal ends of the proximal row and distal ends of the distal row of carpal bones.

The pisotriquetral joint is also a synovial plane joint, but it has a distinct capsule which is supported by the tendon of flexor carpi ulnaris proximally and pisohamate and pisometacarpal ligaments distally.

Palpation

With the exception of the joint between the pisiform and triquetral, the joints between the carpal bones are very difficult to palpate with any degree of accuracy.

• The posterior aspects of the joints of the carpal bones. These can be identified either by relating their position to the metacarpals or by noting any particular features. You can grip each carpal bone between your finger and thumb and move it against the adjacent bone. The joint line remains elusive to the touch.

• The pisotriquetral joint. The medial aspect of the joint line is the easiest to palpate. Run your fingers dorsally for 1 cm from the anterior point of the pisiform on its medial side. Slight movement of the pisiform will emphasize the joint line.

• The midcarpal joint. The joint between the two rows of carpal bones is known as the midcarpal joint. It permits gliding forwards, backwards and from side to side, augmenting the movements of flexion, extension, abduction and adduction at the wrist joint.

Accessory movements

• Side-to-side movement of the pisiform bone. Ask the model to flex the wrist joint slightly and then deviate the joint medially. Ensure that flexor carpi ulnaris is relaxed. The pisiform bone can now be moved from side to side.

• Gliding movement of the carpal bones. Now locate the capitate bone which is situated at the base of the third metacarpal bone. Stabilize the capitate bone by gripping it between your index finger anteriorly and your thumb posteriorly. You will be able to glide the surrounding carpal bones anteriorly and posteriorly by using a similar grip with the other hand on each bone in turn.

• Side-to-side and anterior and posterior movement of the trapezium bone. Palpate the trapezium at the lateral side of the distal row of carpal bones. Use the same hold as described above and stabilize the rest of the carpus. The trapezium can also be moved anteriorly and posteriorly.

• Note. A good knowledge of the anatomy of the carpal bones is essential and should be combined with practise of this type of movement. Consult the literature on mobilization and manipulations for therapeutic techniques.

• Passive movement between the two rows of carpal bones (the midcarpal joint). Use a similar hold to that described for producing accessory movements of the wrist joint. In this case, stabilize the proximal row of bones with one hand and move the distal row with the other. You should grip the proximal row of carpal bones with the index finger and thumb of your stabilizing hand just distal to the radial and ulnar styloid processes.

• Note. During the anterior, posterior, lateral and medial gliding, however, it is impossible to prevent some movement occurring in the neighbouring joints.

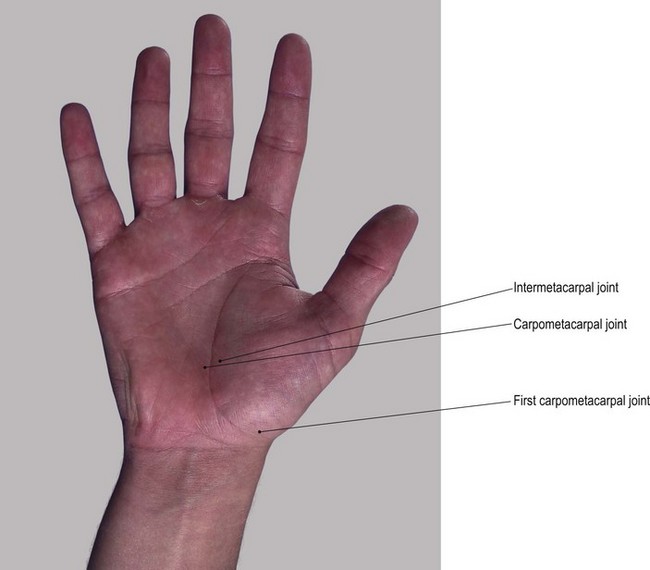

The carpometacarpal joints (Fig. 2.14)

The first metacarpal articulates with the trapezium by means of a synovial saddle (sellar) joint and is separate from the remaining carpometacarpal joints. It is surrounded by a capsule which is lined with synovial membrane and supported by the radial carpometacarpal, anterior and posterior oblique ligaments. The second metacarpal articulates mainly with the trapezoid, having small facets on either side for the trapezium laterally and the capitate medially. The third metacarpal articulates only with the capitate, while the fourth and fifth articulate with the hamate. Except for that of the thumb, they are all plane synovial joints. They have a capsule lined with synovial membrane and are supported by palmar and dorsal ligaments. There is normally an interosseous ligament between the distal ends of the hamate, capitate and trapezoid bones.

Palpation

These joints are only palpable from the posterior aspect.

• The carpometacarpal joints. Trace proximally along the back of the first metacarpal to its enlarged base, beyond which is a depression. At this point, palpate the joint line on either side of the tendon of extensor pollicis longus.

• The common carpometacarpal joint. Dorsally, just proximal to the bases of the second, third, fourth and fifth metacarpals, 2 cm distal to the line of the wrist joint, is a line of depressions between the extensor tendons. These represent the surface marking of the common carpometacarpal joint.

• Movements of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. Ask the model to flex, extend, abduct and adduct the thumb. Now feel the base of the first metacarpal moving on the trapezium.

• Note. There is little movement at the common carpometacarpal joint, except a slight gliding of the surfaces against each other accompanying movements of the hand.

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Movements of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. Ask the model to flex the elbow joint. Stabilize the trapezium with your finger and thumb of one hand. Grip the first metacarpal bone with your other hand. Now you can produce anterior, posterior, medial and lateral gliding of the metacarpal base against the trapezium. You can also produce a limited amount of rotation (i.e. rotation of the metacarpal about its long axis). Slight distraction of the joint is also possible.

• Distraction of the metacarpal bones. Stabilize the remaining carpus with one hand. In turn, grip each metacarpal between your fingers and thumb of the other hand. You can now move each metacarpal base slightly forwards and backwards.

The intermetacarpal joints (Fig. 2.14)

Between the bases of the second to fifth metacarpals are small plane synovial joints surrounded by a capsule lined with synovial membrane and supported by palmar, dorsal and interosseous ligaments. These ligaments allow the joints to be moved individually, giving the hand more mobility and thus more dexterity.

Palpation

Surface marking

• The intermetacarpal joints. On the posterior aspect of the hand, trace proximally up the spaces between the second and third, third and fourth, and fourth and fifth, metacarpal bones until you feel the two bones touching. Palpate the joint line running vertically for approximately 1 cm from the line of the carpometacarpal joint (see above).

Accessory movements

Palpation

It is extremely difficult to move the base of one metacarpal against another, except when they are used as levers.

• Upwards and downwards movement of the metacarpal bones. Ask the model to pronate the forearm. Now grip one metacarpal head between your index finger and thumb of one hand and its neighbour similarly in the other. Move the bones up and down against each other.

• Note. There may be up to a centimetre of movement at the level of the heads, with a much smaller twisting movement of one base against its neighbour.

The metacarpophalangeal joints

Metacarpophalangeal joints are synovial ellipsoid joints between the head of each metacarpal and the proximal end of each associated proximal phalanx. Each joint is surrounded by a fibrous capsule enclosing the head of the metacarpal and the proximal surface of the phalanx.

The capsule is lined with synovial membrane and is supported by strong, cord-like collateral ligaments and a dense palmar ligament. The posterior aspect of the joint is protected by the dorsal expansion of extensor digitorum longus tendon. The palmar ligaments of the second to fifth metacarpophalangeal joints are linked by the deep transverse metacarpal ligament.

• Note 1. Flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb is only 45°, whereas that of the fingers is 90°.

• Note 2. This movement occurs at right angles to that in the other metacarpal joints taking the thumb across the palm.

Palpation

• The metacarpophalangeal joints. The joints of each finger can be palpated just distal to the head of the metacarpal. Ask the model to flex the finger to 90°. Palpate the joint line which appears to be beyond the knuckles, on the anterior surface of the head of the metacarpal (Fig. 2.15). It is easily palpable dorsally on either side of extensor digitorum longus tendons.

• The metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. Palpate this joint posteriorly, just beyond the metacarpal head.

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Movements of the proximal phalanges. Stabilize the metacarpal with one hand and grip the digit with your other hand. Now move the base of the proximal phalanx forwards, backwards and from side to side. You can also rotate the digit about its long axis, producing spin between the two surfaces. If sufficient distraction is applied, you will produce the characteristic ‘pop’.

• Note. This is not normally possible at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb.

The interphalangeal joints

Each finger has two interphalangeal joints, whereas the thumb has only one. They are synovial hinge joints between the head of the more proximal phalanx and the base of the more distal phalanx. These joints are surrounded by a capsule which is lined with synovial membrane and supported by collateral and palmar ligaments.

Palpation

• The interphalangeal joints. The joints are easier to palpate posteriorly. Ask the model to flex the joint to 90°. Now trace distally down the back of each phalanx. Palpate the joint line just beyond the slightly expanded head. It is covered centrally by the expansion of extensor digitorum (dorsal digital expansion).

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Rocking. Ask the model to pronate the forearm and to flex the interphalangeal joint to approximately 30°. Stabilize the more proximal phalanx with one hand and grip the more distal phalanx between fingers and thumb of your other hand. You can now rock the base of the more distal phalanx from side to side. This movement often causes a ‘cracking’ sound.

• Forwards and backwards gliding. It is possible, but not easy, to produce a slight forwards and backwards gliding of the base on the head.

• Distraction. This movement is limited by the tight collateral ligaments. The space gained between the articular surfaces is only a fraction of that gained at the metacarpophalangeal joints.

Muscles

The muscles that move the arm

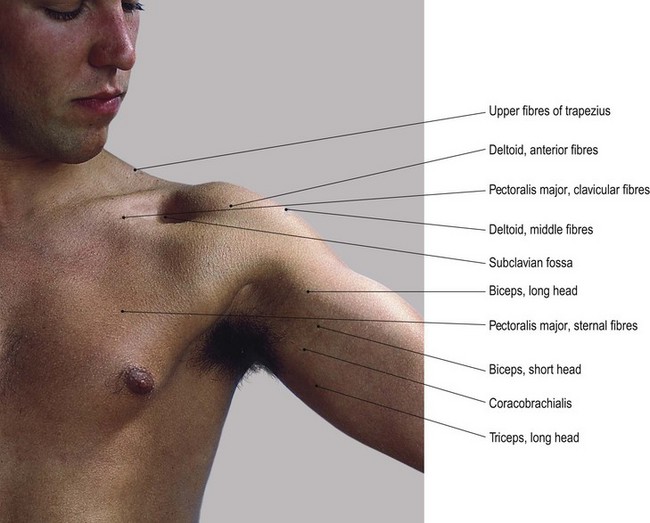

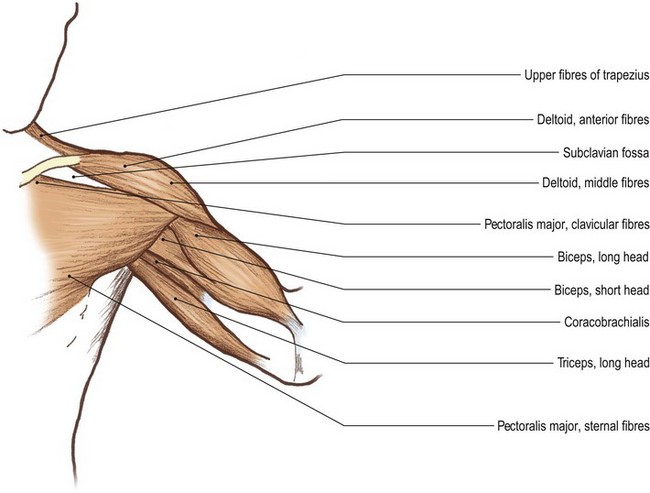

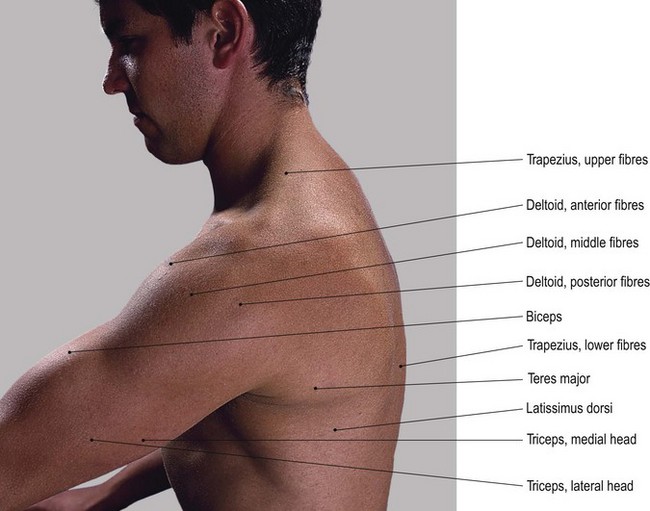

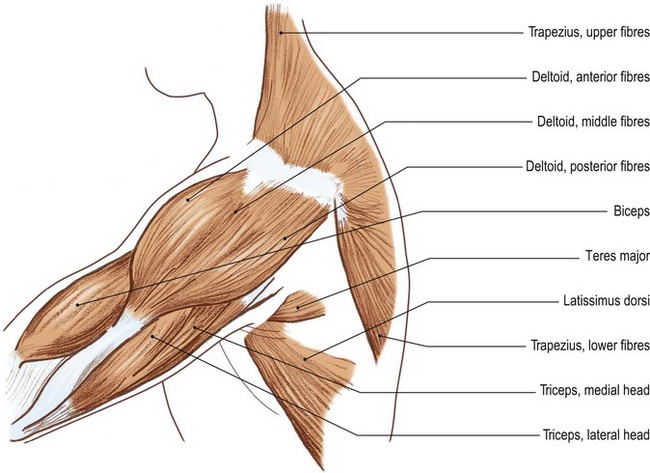

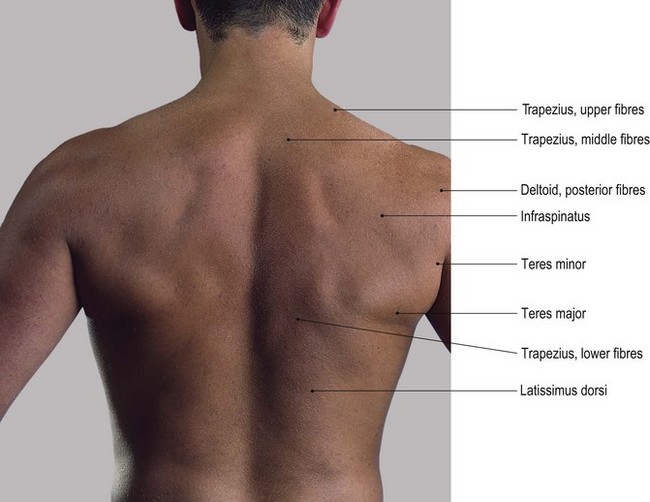

Deltoid (Figs 2.16 and 2.17)

The deltoid is a triangular or delta-shaped muscle situated on the lateral aspect of the shoulder joint. It comprises anterior, middle and posterior sections. These fibres arise above from the lateral end of the anterior border of the clavicle, anterior, lateral and posterior borders of the acromion process, and the lower lip of the spine of the scapula, respectively. They all unite below to attach to the deltoid tubercle on the lateral side of the humerus.

Below the pectoral girdle, the anterior fibres of deltoid can be seen some 3 cm below the lateral lip of the acromion, level with the greater tuberosity of the humerus. This delta-shaped muscle also covers the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder joint and feels thick and well developed.

Palpation

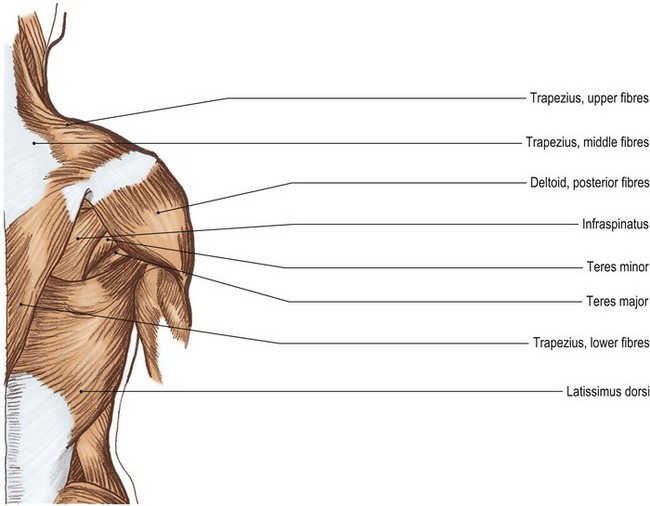

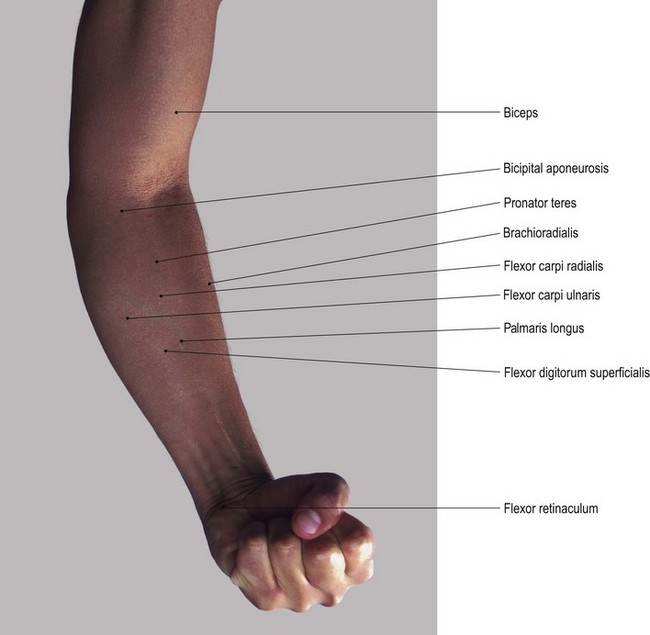

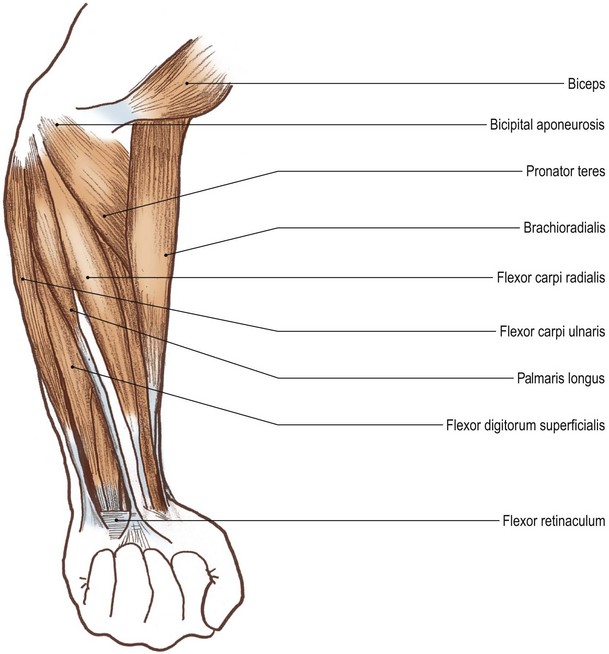

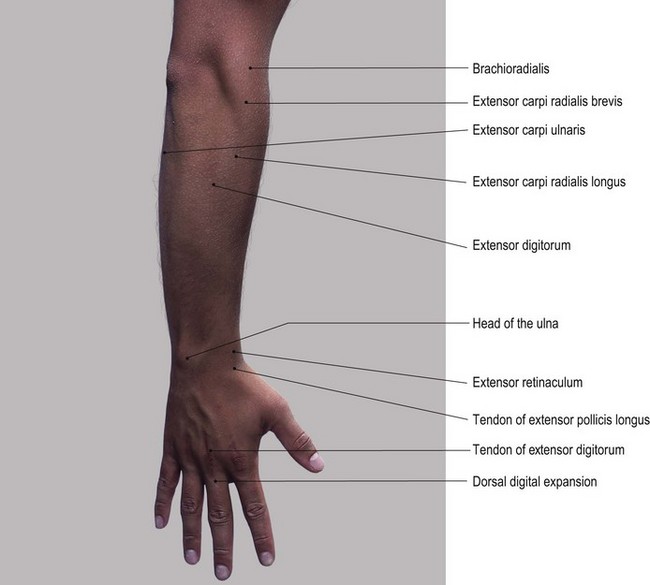

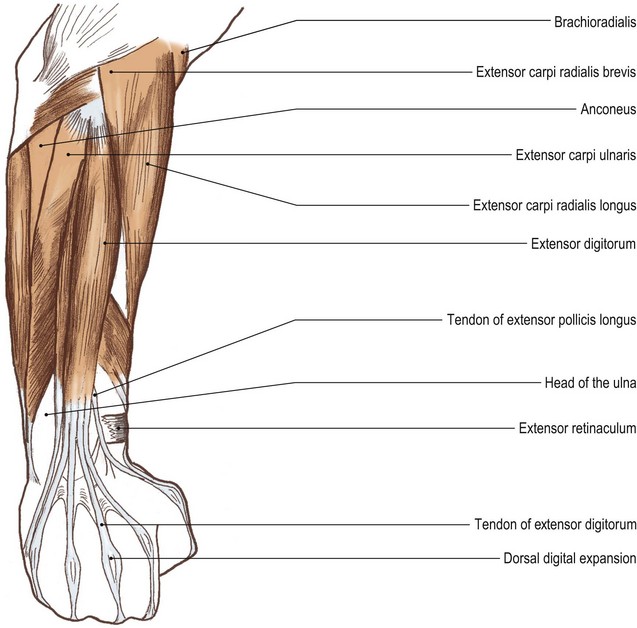

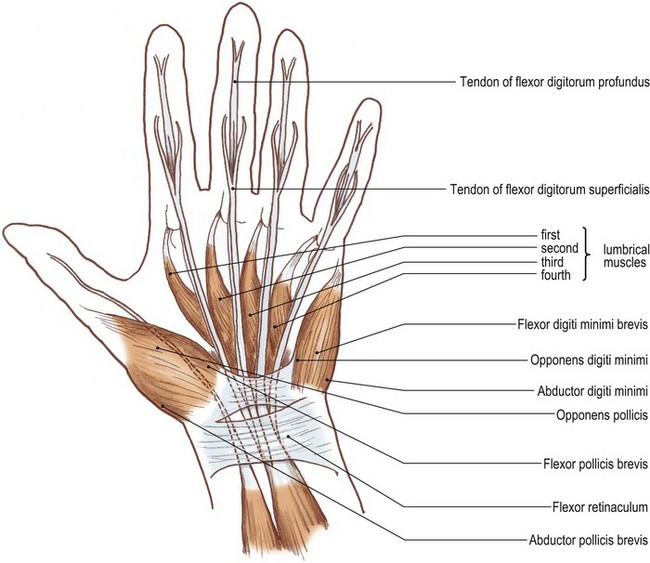

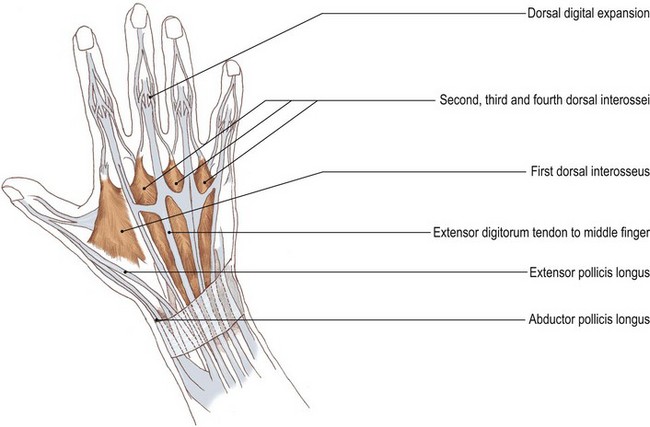

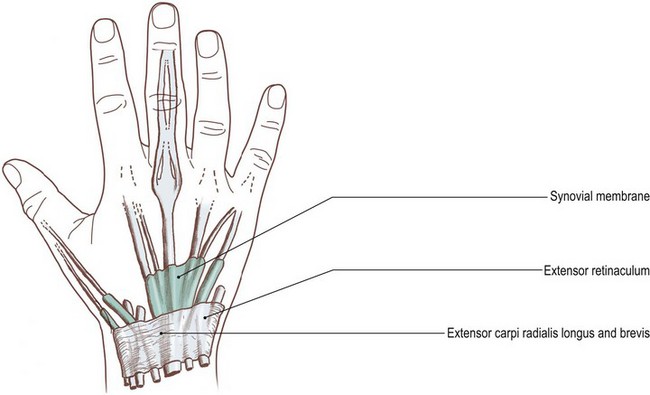

For palpation in this region, the model should be in the standing or sitting positions.