Concepts and Principles of Movement

After reviewing this chapter, the reader will be able to discuss:

1 The components of and differences among the three models of the movement system.

2 How the muscular, nervous, and skeletal systems are affected by repeated movements and sustained postures.

3 How repeated movements and sustained postures contribute to the development of musculoskeletal pain syndromes.

4 The concept of relative flexibility, its relationship to muscle stiffness, and its implications in the role of exercise to stretch muscles.

5 The role of a joint’s directional susceptibility to movement in the development of a musculoskeletal pain syndrome.

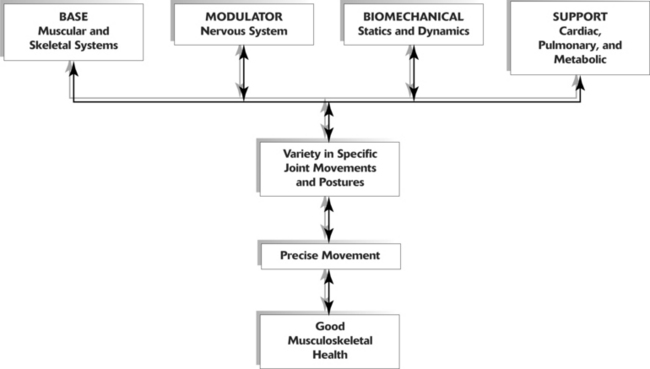

Kinesiologic Model

This text discusses musculoskeletal pain syndromes arising from tissue alterations that are caused by movement. Movement is considered a system that is made up of several elements, each of which has a relatively unique basic function necessary for the production and regulation of movement. Various anatomic and physiologic systems are components of these basic elements (Figure 2-1). To understand how movement induces pain syndromes, the optimal actions and interactions of the multiple anatomic and physiologic systems involved in motion must be considered. The optimal function and interaction of the elements and their components are depicted in the following kinesiologic model.

The elements of the model are (1) base, (2) modulator, (3) biomechanical, and (4) support. The components that form the base element, the foundation on which movement is based, are the muscular and skeletal systems. The components of the modulator element regulate movement by controlling the patterns and characteristics of muscle activation. The modulator element of motion is the nervous system, because of its regulatory functions (described in the sciences of neurophysiology, neuropsychology, and physiologic psychology). Components of the biomechanical element are statics and dynamics. Components of the support element include the cardiac, pulmonary, and metabolic systems. These systems play an indirect role because they do not produce motion of the segments but provide the substrates and metabolic support required to maintain the viability of the other systems.

Every component of the elements is essential to movement because of the unique contributions of each; however, equally essential is the interaction among the components. Each has a critical role in producing movement and is also affected by movement. For example, muscular contraction produces movement, and movement helps maintain the anatomic and physiologic function of muscle. Specifically, movement affects properties of muscle, such as tension development, length, and stiffness, as well as the properties of the nervous, cardiac, pulmonary, and metabolic systems. (The changes in these properties are discussed in detail later in this chapter.)

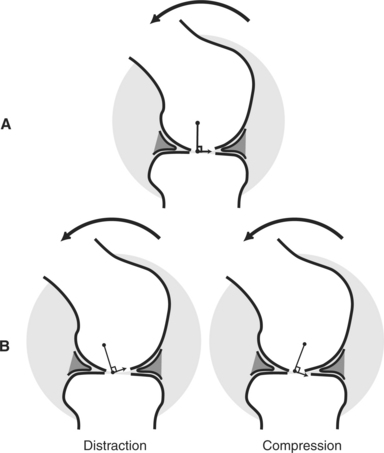

Clinical Relevance of the Model

Optimal function of the movement system is maintained when there is periodic movement and variety in the direction of the movement of specific joints. For example, a posture should not be sustained for longer than 1 hour, based on studies of the effects of sustained forces. McGill and associates have shown that 20 minutes in a position of sustained flexion can induce creep in the soft tissues, requiring longer than 40 minutes for full recovery.41 Two types of effect on soft tissues from sustained forces are described: (1) time-dependent deformation of soft tissues, and (2) soft tissue adaptations involving protein synthesis.23 A study by Light and colleagues demonstrates that 1 hour per day of sustained low-load stretching produces significant improvement in range-of-knee extension in patients with knee flexion contractures when compared with high-load stretching produced during short duration.37 The implication is that short duration stretching produces temporary deformation of soft tissues, but 1 hour of stretching may be a sufficient stimulus for long-term soft-tissue adaptations. When there is variety in the stresses and directions of movement of a specific joint, the supporting tissues are more likely to retain optimal kinesiologic behavior (defined as precision in movement) than when there is constant repetition of the same specific movement or maintenance of the same specific position.

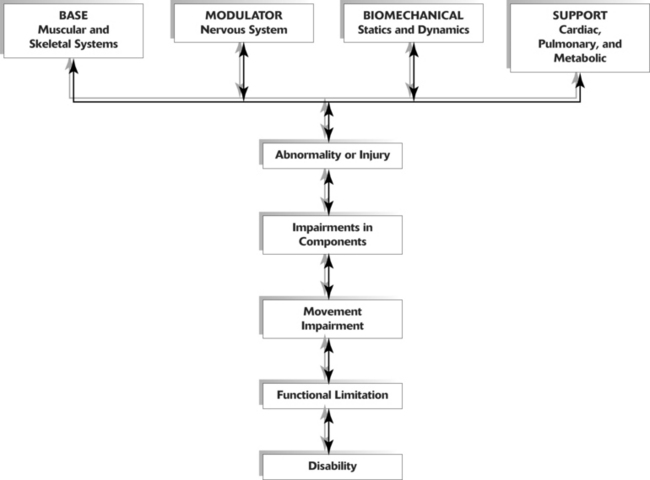

Pathokinesiologic Model

Pathokinesiology is described by Hislop as the distinguishing clinical science of physical therapy, and it is defined as the study of anatomy and physiology as they relate to abnormal movement.25 Based in part on word construction and in part on clarification of causative factors, pathokinesiology emphasizes abnormalities of movement as a result of pathologic conditions. The pathokinesiologic model (Figure 2-2) depicts the role of disease or injury as producing changes in the components of movement, which result in abnormalities of movement. In the Nagi model of disablement,45 disease leads to impairments that cause functional limitations with the possible end result of disability. Impairments are defined as any abnormality of the anatomic, physiologic, or psychologic system. Therefore abnormalities of any component system or of any movement are considered impairments.

In the pathokinesiologic model, a pathologic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, produces lesions in the skeletal components because of the degenerative changes in joints. The degenerative joint changes cause alterations in movement of the joint and possibly in movements involved in functions such as ambulating or self-care activities. This model suggests that in addition to the changes in skeletal components, such as joint structures and movement characteristics, there are also changes in the neurologic, biomechanical, cardiopulmonary, and metabolic components. Depending on the severity of the movement impairments, the consequence can be disability.

Similarly, a cerebral vascular accident produces pathologic abnormalities in the central nervous system with the consequence often a form of paresis and movement impairment. Although the primary lesion is in the nervous system, all secondary changes in other components of the movement system must be considered to ensure optimal management of the patient’s movement impairment.

Clinical Relevance of the Model

In the pathokinesiologic model, the pathologic abnormality is the source of component impairments, which then causes movement impairments, functional limitations, and often disability. Because of the interaction of the component systems as depicted in the model, identifying the secondary changes in each system is as important as understanding the primary pathologic effect on a system component. For example, in the case of hemiparesis, the movement dysfunction is the result of an abnormality involving the nervous system. Factors contributing to movement dysfunction include but are not limited to (1) an inability of the central nervous system to recruit and drive motor units at a high frequency,56 (2) the co-activation of antagonistic muscles,13 (3) a secondary atrophy of muscles that compromise contractile capacity,7 (4) the stiffness of the muscle,57 (5) a loss of range of motion from contracture,21 (6) the biomechanical alterations that are the result of insufficient and inappropriate timing of muscular activity,12,51 and (7) an internal sensory disorganization.12 In addition, the alterations of metabolic demands during activity and the aerobic conditioning of the patient must all be considered as contributing factors in the movement impairment. The degree of involvement of each of these factors and their influence on function varies from patient to patient. Physical examination formats should address all these factors and their relative importance to the patient’s functional problem. Decisions that lead to the formation of the management program must be based on the potential for remediation of each of the contributing factors and ranked according to their relative importance to the functional outcome of the patient.

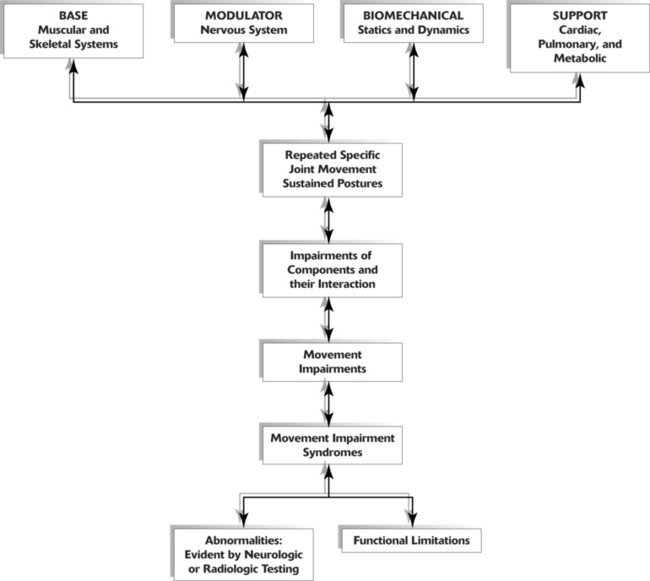

Kinesiopathologic Model

A common belief is that movement impairments are the result of pathologic abnormalities, but the thesis of this text is that movements performed in daily activities can also cause impairments that eventually lead to pathologic abnormalities. Therefore a different model is proposed to characterize the role of movement in producing impairments and abnormalities. The empirical basis of this model stems from observations that repetitive movements and sustained postures affect musculoskeletal and neural tissue. The cumulative effect of repetitive movements is tissue damage, particularly when the movements deviate from the optimal kinesiologic standard for movement. Human movements involve similar internal and external forces as do mechanical systems.49 In mechanical systems, maintaining precise movement is of such importance that the science of tribology is devoted to the study of factors involved in movement interactions. Tribology is defined as the study of the mechanisms of friction, lubrication, and wear of interacting surfaces that are in relative motion.1 Based on the similarities of biomechanical and mechanical systems, the premise for ensuring the efficiency and longevity of the components of the human movement system is maintaining precise movement of rotating segments. Although the adaptive and reparative properties of biological tissues permit greater leeway in maintaining their integrity than do nonbiologic materials, it is reasonable to assume that maintaining precise movement patterns to minimize abnormal stresses is highly desirable.

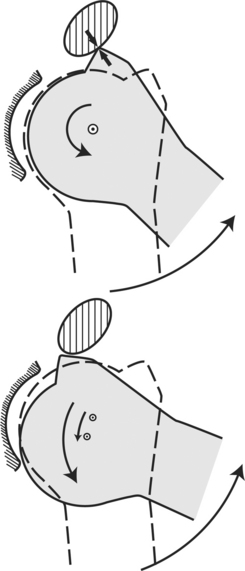

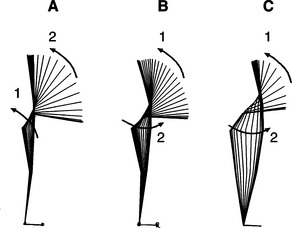

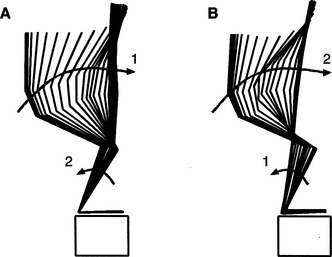

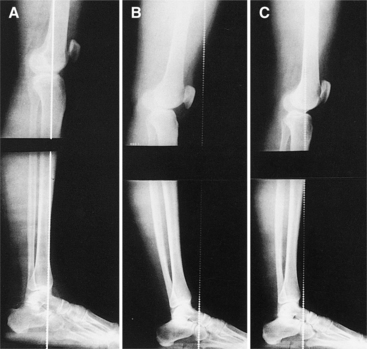

A useful criterion for assessing precise or balanced movement is observing the path of instantaneous center of rotation (PICR) during active motion (Figure 2-3). The instantaneous center of rotation (ICR) is the point around which a rigid body rotates at a given instant of time.48 The PICR is the path of the ICR during movement. In many joints the PICR is not easily analyzed and radiologic methods are necessary to depict the precision of the motion (Figure 2-4). These radiologic methods use movements that are performed passively and under artificial conditions. The joints in which the PICR is difficult to observe clinically include those of the knee and spine. The PICR of the scapulothoracic (Figure 2-5) and glenohumeral (Figure 2-6) joints can be observed visually, but it cannot be easily quantified.

Figure 2-3 As the knee moves from flexion to extension, successive instantaneous centers can be mapped, which is known as the instant center pathway. In the normal knee, the pathway is semicircular and located in the femoral condyle. (Modified from Rosenberg A, Mikosz RP, Mohler CG: Basic knee biomechanics. In Scott WN, editor: The knee, St Louis, 1994, Mosby.)

Figure 2-4 PICR of the knee. Line drawn perpendicular from the instantaneous center to the joint surface is normally parallel to the joint surface, indicative of a sliding motion between surfaces. (Modified from Rosenberg A, Mikosz RP, Mohler CG: Basic knee biomechanics. In Scott WN, editor: The knee, St Louis, 1994, Mosby.)

Knowledge of the PICR and range of motion of the joint both guide observations and judgments about movement. Although it is rarely referred to specifically, the observation of the PICR is the guideline that physical therapists use to judge whether the joint motion is normal or abnormal. Anatomic and kinesiologic factors that determine the PICR and the pattern of joint movement are (1) the shape of joint surfaces, (2) the control by ligaments, and (3) the force-couple action of muscular synergists.73

With normal or ideal movement of joints, the question arises, “What is the cause of deviations in joint movement when a pathologic condition or specific injury is not the problem?” Suggested causes of deviations in joint movement patterns are repeated movements and sustained postures associated with daily activities of work and recreation. For example, baseball pitchers and swimmers perform repeated motions and commonly experience shoulder pain.16,31 Prolonged sitting has been cited as a factor in the development of back pain.52 Cyclists who spend 3 hours riding their bicycles in a position of lumbar flexion have a reduced lumbar curve when compared with control subjects who do not ride bicycles.10

Therapists and other clinicians involved in exercise prescription believe that repeated movements can be used therapeutically to produce desired increases in joint flexibility, muscle length, and muscle strength, as well as to train specific patterns of movement. All individuals who participate in exercise accept the fact that repeated movements affect muscle and movement performance. Thus these individuals should also accept the idea that repeated motions of daily activities, as well as those activities of fitness and sports, may also induce undesirable changes in the movement components. Stretching and strengthening exercises performed for shorter than 1 hour are believed to produce changes in muscular and connective tissues. However, repeated movements and sustained postures associated with everyday activities that are performed for many hours each day may eventually induce changes in the components of the movement system. The inevitable result is the development of movement impairments, tissue stress, microtrauma, and eventually macrotrauma. In accordance with this proposed theory, the effects of repeated movements and sustained postures modify the kinesiologic model so that it becomes a kinesiopathologic model (Figure 2-7), that is, a study of disorders of the movement system.

Clinical Relevance of the Model

The kinesiopathologic model serves as a general guide for identifying the components that have been altered by movement. Identifying the alterations or suboptimal functions of components provides a guide to prevention, diagnosis, and intervention. If there is suboptimal function of any component of an element, operationally defined as an impairment, it may be considered a problem and corrected before the client develops musculoskeletal pain. Identifying impairments and correcting them before they become associated with symptoms is using the information incorporated in the model as a guide to prevention. If the impairment is not corrected and the repeated movements continue, the sequence of movement impairment leading to microtrauma and macrotrauma progresses with the consequence of pain and, eventually, identifiable tissue abnormalities.

If pain is present, the kinesiopathologic model can be used to identify all the contributing factors that must be addressed in a therapeutic exercise program. Reversal of the deleterious sequence requires the identification and correction of the movement and component impairments. More important than developing a therapeutic exercise program, the performance of functional activities that cause pain must be identified and corrected.

Based on clinical examinations, muscular, skeletal, and neurologic component impairments have contributed to musculoskeletal pain syndromes. (Each of these impairments is individually discussed in this chapter.) The key to diagnosis and effective intervention is the identification of all impairments contributing to a specific movement impairment syndrome. (Syndromes and their multiple associated impairments are discussed in the relevant chapter on diagnostic categories.)

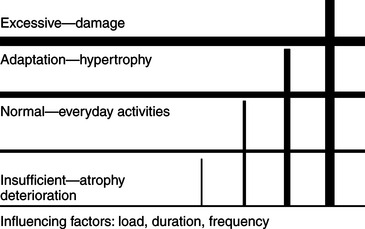

How do repeated movements and sustained postures cause changes in the component systems? The prevailing characteristic of the muscular system is its dramatic and rapid adaptation to the demands placed on it. Most often, adaptations such as changes in strength are considered advantageous; however, changes in strength can also be detrimental and may contribute to movement impairments. Muscles become longer or shorter as the number of sarcomeres in series increases or decreases. Everyday activities can change the strength and length of muscles that alter the relative participation of synergists and antagonists and, eventually, the movement pattern.

Identifying the types of changes that occur in muscle and the causative factors for these changes is the key to maintaining or restoring optimal musculoskeletal health. Changes in muscle occur even when an individual lives a sedentary lifestyle; muscular changes are not limited to those who perform physically demanding work. The most sedentary occupation or lifestyle is associated with some form of repeated movement or sustained posture. For example, individuals who sit at a desk during most of the day perform many rotational or side-bending movements of their spine when they move from a writing surface to the computer or when they reach for the telephone or into a file drawer.

Movements repeated at the extremes of frequency (either high or low) and movements that require the extremes of tension development (either high or low) can cause changes in muscle strength, length, and stiffness. Similarly, sustained postures and particularly those postures that are maintained in faulty alignments can induce changes in the muscles and supporting tissues that can be injurious, especially when the joint is at the end of its range.70

One of the most surprising characteristics of muscle performance evident to those who perform specific manual muscle testing is the presence of weakness, even in those individuals who regularly participate in physical activities. A frequently held assumption is that participation in daily activities or participation in sports places adequate demands on all muscles, ensuring normal performance. However, careful and specific muscle testing demonstrates that several muscles commonly test weak. For example, muscles frequently found to be weak are the lower trapezius, external oblique abdominal, gluteus maximus, and posterior gluteus medius. Even individuals who are active in sports demonstrate differences in the strength of synergistic muscles; one muscle can be notably weaker than its synergist.

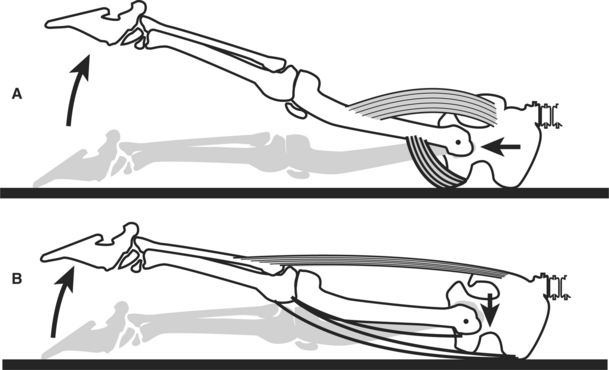

The following example illustrates how repeated movements can alter muscle performance and lead to movement impairments. When the gluteus maximus and piriformis muscles are the dominant muscles producing hip extension, their proximal attachments provide more optimal control of the femur in the acetabulum than do the hamstring muscles. The attachments of the piriformis and gluteus maximus muscles onto the greater trochanter and intertrochanteric line of the femur provide control of the proximal femur during hip extension. The gluteus maximus through the iliotibial band also attaches on the tibia distally. Therefore this muscle is producing movement of both the proximal and distal aspects of the thigh, which reinforces the maintenance of a relatively constant position of the femoral head in the acetabulum during hip extension (Figure 2-8).

Figure 2-8 Hip extension in prone. A, Normal hip extension with constant position of femur in acetabulum; B, Abnormal hip extension because of anterior glide of femoral head.

The normal pattern can become altered, particularly in distance runners who develop weakness of the iliopsoas and gluteus maximus muscles. In contrast, the tensor fascia lata (TFL), rectus femoris, and hamstring muscles often become stronger and more dominant in distance runners than in nonrunners. The lack of balance in the strength and pattern of activity among all the hip flexor and extensor muscles can contribute to movement impairments, because each muscle has a slightly different action on the joint to which it attaches. When one in the group becomes dominant, it alters the precision of the joint motion. In the scenario where the activity of the hamstring muscles is dominant and the gluteus maximus muscle is weak, the result can be hamstring strain and a variety of hip problems that are painful. One plausible reason hip joint motion becomes altered is that the hamstring muscles, with one exception, originate from the ischial tuberosity and insert into the tibia. (The exception is the short head of the biceps femoris muscle, which attaches distally on the femur.) Because the hamstring muscles, with the exception of the short head, do not attach into the femur, they cannot provide precise control of the movement of the proximal end of the femur during hip extension. When the hamstring muscular activity is dominant during hip extension, the proximal femur creates stress on the anterior joint capsule by anteriorly gliding during hip extension rather than maintaining a constant position in the acetabulum (see Figure 2-8). This situation can be exaggerated if the iliopsoas is stretched or weak and is not providing the normal restraint on the femoral head.

These changes in dominance are not presumed; they are confirmed through manual muscle testing and careful monitoring of joint movement. Manual muscle testing32 is used to assess the relative strength of synergists and the identification of muscle imbalances. Carefully monitoring the precision of joint motion as indicated by the PICR is also necessary when the muscle imbalance has produced a movement impairment. For example, monitoring the greater trochanter during hip extension will identify which muscles are exerting the dominant effect. The greater trochanter will move anteriorly when the hamstrings are the dominant muscles. In contrast, the greater trochanter will either maintain a constant position or move slightly posteriorly when the gluteus maximus and piriformis muscles are the prime movers for hip extension.

Muscle testing identifies the muscles that demonstrate performance deficits as a result of weakness, length changes, or altered recruitment patterns. In addition to reduced contractile capacity of muscle, other factors such as length and strain can be responsible for altered muscle performance, and the muscle can score a less than normal grade in a manual muscle test. The different mechanisms that contribute to these factors can be identified by performance variations during manual muscle testing and are discussed in this chapter.

Base Element Impairments of the Muscular System

To design an appropriate intervention program, it is necessary to identify the specific factors that are causing the impairments of the muscular system and contributing to movement impairment. Factors affecting the contractile capacity of the muscle are the number of muscle fibers, the number of contractile elements in each fiber (atrophy or hypertrophy), the arrangement (series or parallel), the fundamental length of the fibers, and the configuration (disruption, over-lengthened, or overlapped) of the contractile elements.

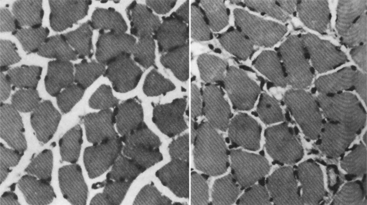

Muscular force is in proportion to the physiologic cross-sectional area.36 The physiologic cross-sectional area is a function of the number of contractile elements in the muscle (Figure 2-9). Muscle will atrophy, or lose contractile elements, when it is not routinely required to develop other than minimal tension. Conversely, the muscle cells hypertrophy when routinely required to develop large amounts of tension, as long as the tension demands are within the physiologic limit of its adaptive response. The change in size (circumference) of a muscle occurs either by a decrease in sarcomeres (atrophy) (Figure 2-10) or an increase in sarcomeres (hypertrophy) (Figure 2-11). In hypertrophy the addition of sarcomeres in parallel is accompanied by the addition of sarcomeres in series, though to a lesser extent than those added in parallel.

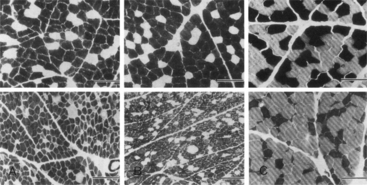

Figure 2-10 Atrophy of muscle. Micrographs from normal muscles (top panel). Micrographs from immobilized muscles illustrating atrophied muscles where the sarcomeres have decreased in diameter (bottom panel). (From Leiber RL et al: Differential response of the dog quadriceps muscle to external skeletal fixation of the knee, Muscle Nerve 11:193, 1988.)

Figure 2-9 Structure of skeletal muscle. A, Skeletal muscle organ, composed of bundles of contractile muscle fibers held together by connective tissue. B, Greater magnification of single fiber showing small fibers, myofibrils in the sarcoplasm. C, Myofibril magnified further to show sarcomere between successive Z lines. Cross striae are visible. D, Molecular structure of myofibril showing thick myofilaments and thin myofilaments. (From Thibodeau GA, Patton KT: Anatomy & physiology, 3e, St Louis, 1996, Mosby.)

Figure 2-11 Hypertrophy of muscle. Cross-section of control rat soleus muscle (left). Cross-section of hypertrophied rat soleus muscle (right). (From Goldberg AL et al: Mechanism of work-induced hypertrophy of skeletal muscle, Med Sci Sports 3:185, 1975.)

Decreased Muscle Strength Caused by Atrophy

One cause of muscle weakness is a deficiency in the number of contractile elements (actin and myosin filaments) that make up the sarcomere structure of the muscle. Atrophy of a muscle is not typically associated with pain during either contraction or palpation. A lack of resistive load on muscle can cause atrophy, not only by reducing the numbers of sarcomeres in parallel and, to a lesser extent, in series, but also by decreasing the amount of connective tissue.

The decreased number of sarcomeres and the decreased amount of connective tissue can affect both the active36 and passive9 tension of a muscle, which affects the dynamic and static support exerted on each joint it crosses. The effect is diminished capacity for the development of active torque and less stability of the joint controlled by the muscle. For example, if the peroneal muscles of the leg are weak, the motion of eversion will be weak and the passive stability that helps restrain inversion will be diminished.

The passive tension of muscles also affects joint alignment. When the elbow flexor muscles are weak or have minimal passive tension, the elbow remains extended when the shoulder is in neutral. When the elbow flexors are hypertrophied from weight training, the resting position of the elbow joint is often one of flexion. Because atrophy means a deficiency of contractile elements, the size of a muscle (cross-sectional area) and its firmness can be used as guides to assess strength. For example, poor definition of the gluteal muscles is usually a good indication that these muscles are weak, particularly when the definition of the hamstring muscles suggests hypertrophy. Examiners should not rely solely on observation, but they should perform a manual muscle test to confirm or refute the hypothesis.

As mentioned, when muscle in the normal individual is tested, it is not uncommon to find deficient performances, even in those who exercise regularly. These deficiencies develop because subtle differences in an individual’s physical structure and manner of performing activities can have a major effect on the participation of different muscles. When an individual shorter than 5 feet, 2 inches in height stands from sitting in a standard chair, the demands placed on his or her hip and knee extensor muscles are not the same as those in the individual who is 6 feet, 2 inches in height or who has long tibias that cause the knees to be higher than the hips when sitting. A greater demand is placed on the extensor musculature when the knees are higher than the hips while sitting and the individual stands from a sitting position. These differences become apparent when standing from a low chair or sofa. When individuals use their hands to push up from a chair, they also contribute to the weakness of the hip and knee extensor muscles by decreasing their participation.

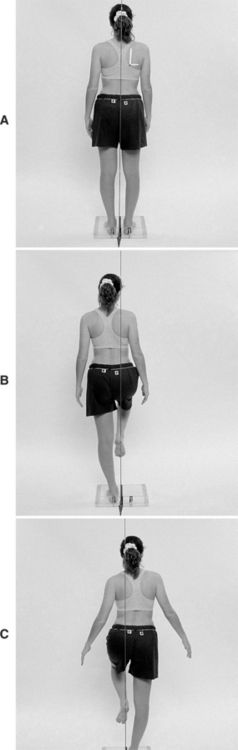

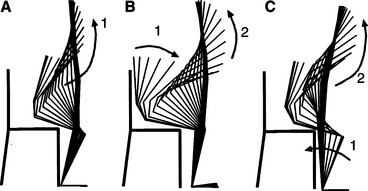

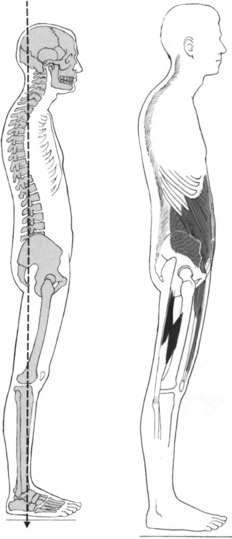

Another example of altering the use of specific muscles is seen in the individual who returns to an upright position from a forward flexed position by swaying the hips forward rather than maintaining a relatively fixed position of the hips. The individual with the relatively fixed position of the hips lifts the length of the pelvis and trunk by extending the hips and back (Figure 2-12). Typically, individuals who sway their pelvis forward have weak gluteus maximus muscles. There are numerous ways in which slight subtleties in movement patterns contribute to specific muscle weaknesses. The relationship between altered movement patterns and specific muscle weaknesses requires that remediation addresses the changes to the movement pattern; the performance of strengthening exercises alone will not likely affect the timing and manner of recruitment during functional performance.

Figure 2-12 Return from forward bending using three different strategies. Optotrak depiction of movement of markers placed at the head of the fifth metatarsal, ankle joint, lateral epicondyle of the knee, greater trochanter, iliac crest, and tip of shoulder. A, The motion is initiated by hip extension, followed by immediate and continuous lumbar extension, and is accompanying the rest of the hip motion. B, The motion is initiated by lumbar extension and followed by hip extension. C, In the forward-bending position, the subject is swayed backward with the ankles in plantar flexion. The return motion is a combination of ankle dorsiflexion and hip extension by forward sway of the pelvis. (Courtesy of Amy Bastian, PhD, PT.)

Clinical Relevance of Muscle Atrophy

Identifying specific muscle weakness requires manual testing. When a muscle is atrophied, it is unable to hold the limb in the manual test position or at any point in the range when resistance is applied. The muscle is not painful when palpated or when contracting against resistance. When a muscle tests weak, the therapist carefully examines movement patterns for subtleties of substitution. Correction of these movement patterns in addition to a specific muscle-strengthening program is required for an optimal outcome. Another factor that must be corrected is the habitual use of any position or posture that subjects the muscle to stretching, particularly when the patient is inactive (e.g., sleeping). Sleeping postures can place the muscles of the hip and shoulder in stretched positions. (This type of stretch weakness is discussed in the section on lengthened muscle in this chapter.)

To initiate the reversal of muscle atrophy, the patient’s ability to activate the muscle volitionally is augmented. Studies indicate that after 2 weeks of training, 20% of the change in muscle tension development can be attributed to muscular factors (contractile capacity) and 80% from enhanced neural activation.43 Training specific muscles is particularly important when the problem is an imbalance of synergists rather than generalized atrophy.

Exercises that emphasize major muscle group contraction can contribute to the imbalance, rather than correct it. When the patient performs hip abduction with the hip flexed or medially rotated, the activities of the TFL, anterior gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus muscles are enhanced to a greater extent than the activity of the posterior gluteus medius muscle, even though all these muscles are hip abductors. The end result is hip abduction with hip flexion and medial rotation rather than pure abduction. Resistance exercises performed on machines can contribute to imbalances unless proper precautions are observed.

Approximately 4 weeks of strengthening exercises are required to verify the morphologic increase in muscle cross-sectional area.43 Studies at the cellular level suggest that change may be occurring earlier than 4 weeks, which is consistent with the metabolic properties of other proteins. Because 4 weeks is required for changes in the number of contractile elements, early improvements in muscle performance are attributed to neuromotor recruitment. The rate of recruitment and the absolute frequency of activation of muscles are important factors in the performance of producing, improving, and maintaining the tension-generating properties of muscles.

Decreased Muscle Strength Secondary to Strain

Strain can result from excessive stretching for short duration or excessive physiologic loading usually associated with eccentric contraction.35 (Additional discussion of the cellular manifestation of strain is found in the section on increased muscle length in this chapter.) Unless there is an actual tear of muscle fibers and obvious signs of hemorrhage, strain is not readily recognized as a source of muscle weakness. The intervention is different than when the muscle is strained and not merely atrophied.

Muscles that are strained are usually painful when palpated or when contracting. As with atrophy, a strained muscle is weak and unable to hold the limb in any position when resistance is applied throughout the range of motion. The presence of pain is usually an indicator of weakness from strain rather than from atrophy. When the length of the strained muscle is not constrained by its joint attachments, it is elongated in the resting position, such as a dropped or forward shoulder with a strain of the trapezius muscle. Strained muscles need to be rested at the ideal resting length to decrease the elongation of the muscle cells. The strained muscle can be supported by external support such as tape, preferably a type that has a strong adhesive and lacks elasticity. Exercises and active motions should be pain free or cause only mild discomfort.

The same principles used to manage atrophied muscles are applied to strained muscles, once the muscle is no longer painful.

Increased Muscle Strength Caused by Hypertrophy

Studies have shown that when a muscle is subjected to overload conditions, the response is the addition of contractile and connective tissue proteins. The value of hypertrophy in increasing the tension-generating capability of muscle is well known and frequently used by those involved in rehabilitation and athletics. Less appreciated is the effect of hypertrophy on the passive-tension properties of muscle and other connective tissue. Many tissues respond to stress by adapting (see Figure 2-11), which for muscle is hypertrophy. The quantity of connective tissue proteins of ligaments, tendons, and muscle also increases with hypertrophy. Tendons and ligaments become stronger and stiffer when subjected to stress, but they grow weaker when they are not subjected to stress.64,67,72 The result is an increase in the passive tension of these tissues, not just the active tension that is generated by muscle during contraction. (The cellular factors are described in the section on muscle stiffness in this chapter.)

The use of strengthening exercises that are based on requiring muscle to lift maximal loads is well known to physical therapists. Strengthening exercises not only increase the tension-generating capacity of the muscle, but they also increase the stiffness of the muscle and the stability of the joints. Hypertrophy is important in improving muscle control under both active and passive conditions.

Muscle Length

A muscle can become lengthened by one of the following three mechanisms:

1. Prolonged elongated position. Muscle may remain in an elongated position during a prolonged period (hours or days) of rest or inactivity (e.g., elongation of the ankle dorsiflexors by the tension of bed covers during bed rest). This condition is similar to over-stretch weakness and a mild form of strain that does not involve eccentric contraction under load as described by Kendall.32

2. Injurious strain. Muscle may be subjected to injurious strain, which is the disruption of the cross bridges, usually in response to a forceful eccentric contraction. The muscle may then be subjected to continuous tension.

3. Sustained stretching. Muscle may respond to sustained (many days to weeks) stretching during immobilization in a lengthened position with the addition of sarcomeres in series.71

Over-Stretch Weakness

Muscles become weak when they maintain a lengthened position, particularly when the stretch occurs during periods of prolonged rest. A common example is the development of elongated dorsiflexor and shortened plantar flexor muscles in the patient for whom bed rest is prescribed or in the individual who remains supine for a prolonged period without the use of a footboard. This problem is exaggerated when the sheet exerts a downward pull on the feet, causing an additional force into plantar flexion and a consequent lengthening of the dorsiflexor muscles.

Another example is the prolonged stretch of the posterior gluteus medius that occurs while sleeping. This condition is seen particularly in the woman with a broad pelvis who regularly sleeps on her side with her uppermost leg positioned in adduction, flexion, and medial rotation. During manual muscle testing, this patient is unable to maintain the hip in abduction, extension, and lateral rotation—the testing position—or at any point in the range, as the resistance is continually applied by the examiner. The resultant lengthening of the muscle can produce postural hip adduction or an apparent leg length discrepancy when the patient stands.

Another example of prolonged stretch occurs when an individual sleeps in a side-lying position with the lower shoulder pushing forward, causing the scapula to abduct and tilt forward. This prolonged position stretches the lower trapezius muscle and possibly the rhomboid muscles. In the side-lying position, the top shoulder is susceptible to problematic stretching when the arm is heavy and the thorax is large, causing the arm to pull the scapula into the abducted, forward position. This sleeping position can also cause the humeral head in the glenoid to move into a forward position.

There are several characteristics of muscles with over-stretch weakness:

1. Postural alignment that is controlled by the muscle indicates that the muscle is longer than ideal, as in depressed shoulders or in a postural alignment of the hip of adduction and medial rotation.

2. Muscle tests weak throughout its range of motion and not only in the shortened muscle test position.

Case Presentation 1

History.: 20-year-old female college student has developed back pain that is partially attributable to working as a waitress. Radiologic studies indicate she has a C-curve of her lumbar spine with a right convexity. Her left iliac crest is 1 inch higher than her right, and she stands with a marked anterior pelvic tilt.

Symptoms.: The patient complains that her slacks are not fitting correctly. Although she is slender, the patient has a very broad pelvis. She sleeps on her right side with her left leg positioned in hip flexion, adduction, and medial rotation.

Muscle Length and Strength.: Muscle length testing indicates a shortened left TFL. Manual muscle testing indicates that the posterior portion of her left gluteus medius muscle is weak, grading 3+/5. Her external oblique abdominal muscles also test weak, grading 3+/5. In the side-lying position, her left hip adducts 25 degrees and rotates medially to the extent that the patella faces the plinth. A home exercise program that emphasizes strengthening her posterior gluteus medius muscle in the shortened position is prescribed. In the supine position with her hips and knees flexed, she performs isometric contraction of her external oblique abdominal muscles while maintaining a neutral tilt of her pelvis. She then extends one lower extremity at a time. The position for hip flexor length testing is used to stretch the TFL. She also performs knee flexion and hip lateral rotation in the prone position. She is instructed to stand with her hips level and to contract her external oblique abdominal and gluteal muscles. She is also asked to use a body pillow to support her left leg while sleeping to prevent the adduction and medial rotation of her left hip when lying on her right side.

Outcome.: On her second visit 3 weeks later, the patient’s symptoms have greatly improved to only an occasional incident of discomfort. Her iliac crests are level, and her spinal lateral curvature is no longer clinically evident. The anterior pelvic tilt has resolved. She states she no longer has back pain.

Increased Muscle Length Secondary to Strain

Strain is discussed because of the importance of differentiating whether the cause of muscle pain is muscle shortness or excessive muscle length. A common approach to the treatment of painful muscles, particularly those of the shoulder girdle, is applying a cold spray and stretching the muscle.60 Pain is attributed to spasm in the shortened muscle,60 but often the actual length of the muscle is not assessed before applying stretching techniques. Lengthened muscles can also become painful and should not be stretched. For example, when a muscle is subjected to injurious tension by lifting a heavy object, it can become strained. If the muscle remains under continuous tension, it will become elongated and painful. When the postural alignment examination indicates a muscle is elongated, then strain, rather than shortness, is considered the likely cause of pain.

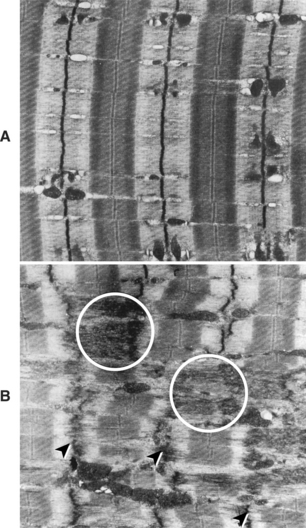

Strain is a minor form of a tear in which the filaments of the muscle have been stretched or stressed beyond their physiologic limit resulting in disruption of the Z-lines to which the actin filaments attach (Figure 2-13). Disruptions that alter the alignment of the myofilaments interfere with the tension-generating ability of these contractile elements.35 The consequence is muscular weakness and, in many cases, pain when the muscle is palpated or when resistance is applied during contraction of the muscle.

Figure 2-13 Micrograph showing normal striation pattern and Z-disks perpendicular to the long myofibrillar axis (A) and various disrupted regions (B). Streaming and smearing of the X-disk material (arrowheads) and extension of the Z-disks into adjacent A-bands (circled areas) are shown. (From Lieber RL, Friden JO, McKee-Woodbum TG: Muscle damage induced by eccentric contractions of twenty-five percent strain, J Appl Physiol 70:2498, 1991.)

If a muscle is strained, the reparative process occurs more readily when the muscle is not subjected to strong resistance or to constant tension. For most muscles the anatomic limits imposed by joints to which the muscles attach help maintain the fibers at their appropriate resting length. Postural muscles of the shoulder and hip can become excessively stretched. For example, if the upper trapezius muscle is strained, weight of the shoulder girdle is excessive for the muscle, the shoulder’s pull on the muscle causes it to elongate, and the muscle is unable to heal. Frequently, strained muscles are painful because they are actually under continuous tension, even when they appear to be at rest. The discomfort is often reduced when the muscle is supported at its normal resting length, the passive tension is reduced, and the patient is instructed to relax the muscle, thereby eliminating any voluntary or involuntary contractile activity. As long as the patient avoids excessive loads on the muscle, it should heal within 3 to 4 weeks.

The typical findings with manual muscle testing of a strained muscle is its inability to support the tested extremity against gravity when positioned at the end of its range. Further, the muscle is unable to maintain its tension at any point in the range when resistance is applied throughout the range, and pain is elicited. Clearly the tension-generating capacity of the muscle is impaired. If the strain is severe, the motion of the joint upon which the muscle is acting will also show quality of movement and range-of-motion impairment.

Case Presentation 2

History.: A 32-year-old woman, whose job requires her to load food trays on a conveyor belt at shoulder height, has a sudden and severe onset of pain between the vertebral border of the right scapula and thoracic spine. The pain began after she attempted to lift a filing cabinet at work. She is seen immediately by a physician who refers her to a physical therapist, prescribing heat to the affected area and shoulder exercises three times a week. After 1 week, the patient returns to light duty at work, but 6 weeks later she still complains of severe pain and she is unable to return to her normal job. A magnetic resonance image of her thoracic spine does not indicate an abnormality.

Symptoms.: She is referred to a second physical therapy clinic. During her initial visit the patient is observed to be approximately 60 pounds overweight, with large arms and breasts and deep indentations on the tops of her shoulders from the pressure of her bra straps. Her facial expression and the manner in which she holds her right arm close to her body with her elbow flexed indicate that she is still in pain. She rates her pain as 6 to 8 on a scale of 10 when attempting any type of shoulder motion and 4 to 5 out of 10 with her arm at rest. (The 10 rating is the most severe.)

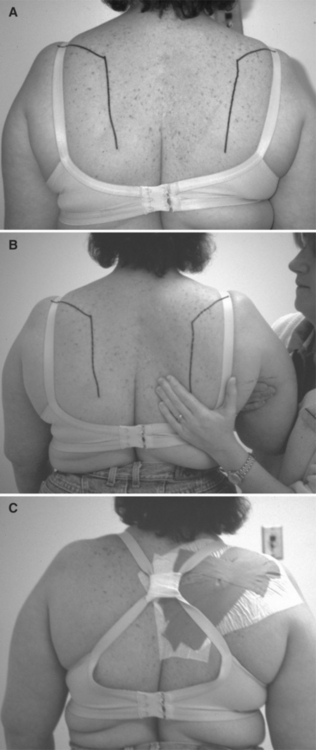

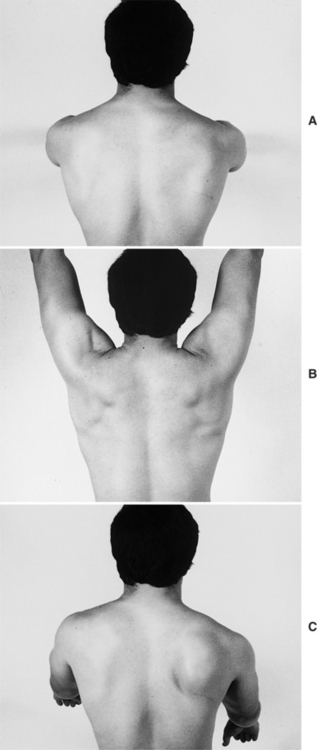

Muscle Length and Strength.: An examination indicates that the right scapula is greatly abducted and tilted anteriorly (Figure 2-14, A). Her scapula is manually positioned in the correct alignment, and her arm and forearm are supported by the physical therapist. After she is instructed to relax the musculature of her right shoulder girdle, she reports her pain has subsided (Figure 2-14, B). A manual muscle test indicates the strength of all components of her trapezius muscle as weak, graded 3—/5. Weakness and pain limit her ability to move through the normal range of motion even in a gravity-lessened position.

Tape (Leukotape P with cover roll underwrap) is applied to the posterior aspect of the right shoulder girdle to support and maintain the scapula in a neutral position and to reduce some of the strain on the trapezius muscle by decreasing the abduction and depression of the scapula. The case report written by Host demonstrates that scapular position can be altered by the application of tape to the posterior shoulder girdle.28

Her bra straps are taped together, bringing them closer to her neck to reduce the downward pull on the lateral aspect of her shoulders. She is also instructed to support her arms on pillows whenever she sits and to support her right arm with her left arm to reduce the downward pull on her shoulder girdle whenever she stands. All shoulder exercises are eliminated for the next 5 days (Figure 2-14, C).

Figure 2-14 Strain of right thoracoscapular muscles. A, Right scapula was abducted and tilted anteriorly. B, Right shoulder was passively supported in the correct alignment to alleviate the strain on the scapular adductor muscles. When the patient relaxed the muscles, her pain was alleviated. C, Bra straps were taped together to bring the straps closer to the neck and to reduce downward pull on the lateral aspect of the shoulder.

Outcome.: On her second visit 4 days later, the patient reports a significant decrease in pain. She has kept her shoulder taped for 2 days. Her skin does not show signs of irritation, and she indicates that the extra support has eliminated her pain at rest. As a result, the tape was reapplied. On her third visit 1 week later, the patient no longer complains of pain at rest, and she can perform 160 degrees of shoulder flexion without pain in the gravity-lessened side-lying position with her arm supported on pillows. In this position the scapula rotates upwardly and adducts during shoulder flexion, in contrast to the limited scapular motion observed during the same movement performed in the standing position. Her shoulder girdle is taped to support the scapula in the neutral position relative to abduction or adduction, elevation or depression, and rotation. The tape remains in place for 2 additional days. She has been taped three times over a 2-week period.

She continues to support her arm passively to reduce the downward pull on her shoulder while sitting and standing. The gradual progression of her exercise program is as follows:

1. Gravity-lessened side-lying shoulder flexion

2. Shoulder flexion facing a wall with her elbow flexed and hand gliding up the wall

3. Shoulder flexion with the elbow extended

4. Shoulder flexion and abduction while lifting light weights

Eight visits during 6 weeks after her initial visit to the second department, she is able to lift a 30-pound tray to shoulder level and has returned to full duty on her job.

Lengthened Muscle Secondary to Anatomic Adaptation—the Addition of Sarcomeres

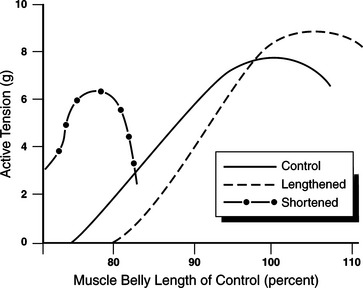

Numerous investigators have demonstrated that when a muscle is maintained in a position of elongation (usually by casting), additional sarcomeres are added in series within the muscle cell. A study by Williams and Goldspink60,72 demonstrates that when such adaptation of the anatomic length occurs, the muscle’s length tension curve is shifted to the right because of the addition of sarcomeres in series.71 However, with both muscles in the same shortened position, the control muscle develops greater tension than the lengthened muscle (Figure 2-15).

Figure 2-15 Anatomic muscle length adaptation. Lengthened muscle develops greater peak tension at a longer length. The same muscle in a shortened position develops less tension than the control muscle in a normal position. (Modified from Gossman, Sahrmann SA, Rose SJ: Review of length-associated changes in muscle. Experimental evidence and clinical implications, Phys Ther 62(12):1799, 1982.)

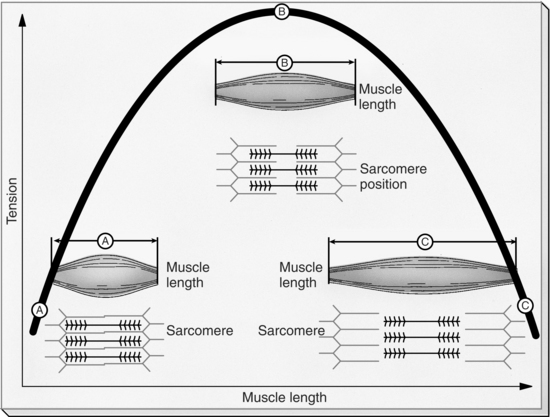

When both the lengthened and control muscles are tested in the same shortened position, the difference in tension between the two (active-insufficiency) can be explained by the existence of greater overlap of actin and myosin filaments in the lengthened muscle. The muscle that generates the greatest tension at its longest length generates the least tension when tested at a shortened length. When the lengthened muscle (increased number of sarcomeres in series) is placed in a shortened position, the myofilaments in each sarcomere are excessively overlapped (Figure 2-16, position A) and thus cannot develop maximal tension. Although such anatomic adaptations have not been histologically demonstrated in human beings, a study comparing right and left hip abductor muscle strength at various muscle lengths supports this interpretation of the hypothesis of length-associated changes.46

Figure 2-16 The length-tension relationship. The maximal strength that a muscle can develop is directly related to the initial length of its fibers. As a short initial length, the filaments in each sarcomere are already overlapped, limiting the tension that the muscle can develop (position A). Maximal tension can be generated only when the muscle is at an optimal length (position B). When the thick and thin myofilaments are too far apart, the lack of the overlap of the filaments prevents the generation of tension (position C). (From Thibodeau GA, Patton KT: Anatomy & physiology, 4e, St Louis, 1999, Mosby.)

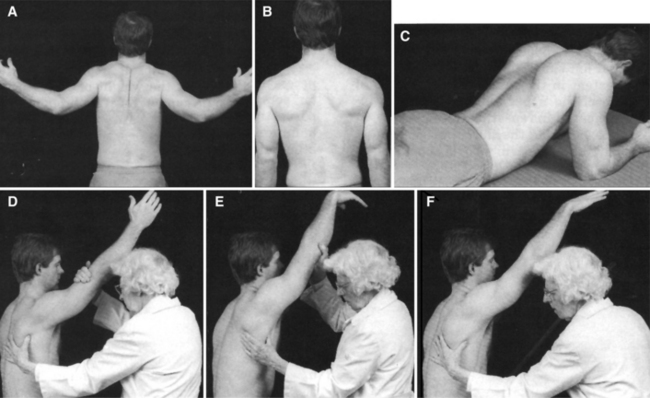

Typically, the result of manual muscle testing of a lengthened (sarcomeres added in series) muscle indicates that it cannot support the joint segment in the shortened test position. The muscle can, however, tolerate strong pressure after it is allowed to lengthen slightly (a change of 10 to 15 degrees in a joint angle). A clinical example is seen in the individual with a habitual posture of adducted scapulae. Manual muscle testing of the serratus anterior muscle with the adducted scapula (Figure 2-17) (a lengthened serratus anterior muscle) indicates the muscle is strong. However, when the scapula is abducted and upwardly rotated to its appropriate muscle testing position (a shortened serratus anterior muscle), the serratus anterior muscle is too weak to hold the scapula in its correct position.

Figure 2-17 A, This subject has routinely performed both bench presses and shoulder adduction exercises with heavy weights, including seated rowing and bent over rowing. The rhomboid muscles have become overdeveloped. B, The abnormal position of scapular adduction is indicative of a lengthened serratus anterior. C, In a prone position and resting on the forearms, there is winging of the scapulae. The serratus is unable to hold the scapula against the thorax. D, When the shoulder is flexed to position the scapula for the serratus test, the scapula does not move to the normal position of abduction. However, the serratus tests strong in this position. E, The scapula is brought forward to the normal position of abduction by the examiner. F, The serratus anterior cannot hold the scapula abducted and upwardly rotated when the examiner releases the arm and the subject attempts to hold it in position. (From Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG: Muscles: testing and function, 4e, 1993, Williams & Wilkins.)

Williams & WilkinsCase Presentation 3

History.: A 50-year-old male swimmer has been experiencing right shoulder pain in the anterolateral aspect. His physician has diagnosed his condition as an impingement syndrome. The exercise program that has been suggested by his swimming coach consists of scapular adduction, shoulder extension, and shoulder rotation exercises. In the resting position his scapulae are adducted with the vertebral borders of each scapula measuring 2¼ inches from the vertebral spine. (Approximately 3 inches is considered normal.) The muscle definition of the rhomboid muscles is more prominent than that of the other thoracoscapular muscles.

Symptoms.: Right shoulder flexion range measures 170 degrees and is associated with pain at the acromion from 150 to 160 degrees of flexion. Scapular abduction and upward rotation is decreased during shoulder flexion. At the completion of flexion, the inferior angle of the scapula is still on the posterior aspect of the thorax and has not abducted and upwardly rotated enough to reach the midaxillary line. When the scapula is passively abducted and upwardly rotated by the therapist during active shoulder flexion, full range of motion is achieved and the patient does not experience pain.

Muscle Length and Strength.: Muscle testing of the serratus anterior muscle indicates that in the abducted position, passively positioned by the physical therapist before instructing the patient to “hold,” the muscle does not support the extremity against gravity in the test position. After the scapula is allowed to adduct slightly, the patient can hold the test position and tolerate maximum resistance.

Outcomes.: The therapeutic exercise program designed for this patient teaches him to abduct and upwardly rotate his right scapula in the gravity-lessened prone and side-lying positions, while avoiding maximal glenohumeral joint ranges of 150 to 160 degrees until the pattern of correct scapular motion is established. The goal is to have the scapula abduct and upwardly rotate so that the inferior angle of the scapula reaches the midaxillary line by the end of the range-of-shoulder flexion. Within 3 weeks of initiating his therapeutic exercise program, the patient no longer experiences shoulder pain; he has full range-of-shoulder motion and has resumed his swimming.

Shortened Muscle Caused by Anatomic Adaptation—the Loss of Sarcomeres

Stretching muscles is a common intervention performed by physical therapists because limited joint motion is a factor in musculoskeletal pain problems. Numerous articles have been written describing the best methods of stretching muscles. The muscles used most often in these studies are the hamstrings. Questions of clinical importance that concern muscle shortness include:

1. How much shortness of a muscle is necessary to affect joint and movement behavior?

2. Under what conditions of performance is shortness a factor?

3. What is the anatomic source of the shortness? In other words, is 10 degrees30 of shortness in the hamstring muscles clinically important? What components of the muscle are producing this limitation?

Most clinicians agree that 45 degrees of shortness in the hamstrings is clinically important. However, changes in muscle length to this extent must involve different anatomic structures than changes from 5 to 10 degrees of a muscle whose effective excursion is 170 degrees. (This calculation is based on the shortest length of the muscle, the knee flexed with the hip extended to the longest length of the muscle, and the knee extended and the hip flexed to 80 degrees.) Certainly most individuals do not need the maximal excursion of the hamstring muscles for their daily or sporting activities; as a result, a deficit of 10 degrees of hamstring muscle excursion is relatively inconsequential.

In contrast, 10 degrees of shortness of the iliopsoas muscle can have an important consequence. Ten degrees of shortness of the iliopsoas muscle prevents hip extension beyond the neutral position. Because hip extension is a required component of normal gait, such a limitation can contribute to a musculoskeletal pain syndrome. The most important issue concerning muscle shortness is not the degree of loss but the percentage of loss of overall muscle excursion and the consequences of such losses on joint behavior during functional activities.

Studies have reported a rapid (i.e., 2- to 4-week time frame) loss of sarcomeres, primarily in series, in muscles immobilized in shortened positions.60,62,71,72 With the loss of sarcomeres, the active length-tension curve of the shortened muscle shifts to the left of the normal length muscle (see Figure 2-15). When a muscle has shortened to the extent that the total number of sarcomeres in series in a fiber is reduced, physiologic correction requires that the sarcomere number be increased. Furthermore, because muscle cells are the most elastic components of muscle, they are the component most easily affected by stretching.

Performing vigorous passive muscle stretching exercises with the intent of achieving a great improvement in joint range of motion in a short period (e.g., 15 to 20 minutes) can disrupt the alignment of the filaments, actually damaging the muscle. Stretching a markedly shortened muscle should be achieved by prolonged elongation with low loads, with immobilization by casting the joint so that the muscle is maintained in a lengthened position or by using the dynamic splint. The percentage of overall change in muscle length that will result in a loss of sarcomeres has not yet been determined, as opposed to the loss of range of motion associated with changes in muscle length from other alterations in the series or parallel elastic components. Less than 10% to 15% of muscle shortness of its overall excursion is caused by short-time–dependent changes in muscle tissues (e.g., creep properties); thus length increases are achieved relatively rapidly. In contrast, muscle length changes of greater magnitude are caused by more permanent structural changes in muscle and support tissues with an actual loss of sarcomeres and perhaps a “laying down” of shorter collagen fibers. When length adaptations are the result of structural changes, different methods of intervention with a longer time course are required.

In many situations, individuals believe their muscles need stretching, not because their joint range of motion is limited but because the muscle cannot be rapidly passively elongated. The individual describes a “stiff” or “tight” feeling. Usually this tightness is not a function of overall muscle excursion; more likely it is a function of muscle stiffness.

The plasticity or mutability characteristic of muscles—adding or losing sarcomeres—has significant clinical implications. A physiologic stimulus for muscle length adaptation is the amount of passive tension applied to the muscle for a prolonged period. When the tension exceeds a certain level, the number of sarcomeres is increased. When the tension falls below a certain level, the number of sarcomeres is decreased. The adaptation in the number of sarcomeres is necessary to maintain the relationship of the overlap between the actin and myosin filaments (see Figure 2-16). Anatomic and kinesiologic relationships suggest that for most joint segments, antagonistic muscles become elongated when muscles around the joint become shortened.

Traditionally, emphasis is placed on stretching muscles that have shortened, but equal emphasis has not been placed on correcting muscles that have lengthened. The lengthened muscle does not automatically adapt to a shorter length when its antagonist is stretched for brief periods. A therapeutic exercise program that stretches the short muscle, such as the hamstring muscles, does not concurrently shorten the lengthened muscle, such as the lumbar back extensors.

The most effective intervention is to shorten the elongated muscle while simultaneously stretching the shortened muscle. This approach is especially important when the lengthened muscle controls the joint that becomes a site of compensatory motion as a result of the limited motion caused by short muscles. For example, during forward bending of the trunk, lumbar flexion can be a compensatory motion for limited hip flexion when the hamstring muscles are short. The most effective intervention is to address the length changes of all the muscles around a joint, not only the shortened muscle. Therefore if the lumbar spine flexes excessively (greater than 20 degrees), the back extensor muscles should be shortened along with stretching the hamstring muscles.

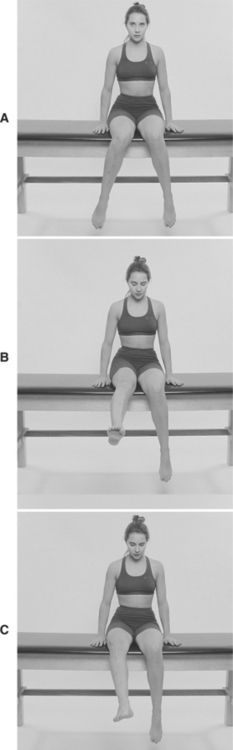

An effective method for correcting anatomic length adaptation is to contract the lengthened muscle while it is in a shortened position and to simultaneously stretch the shortened muscle. The therapeutic exercises that address both problems of the last example are (1) actively extend the knee while sitting to stretch the hamstring muscles, and concurrently (2) actively contract the back extensor muscles to maintain slight back extension and shorten the back extensor muscles. The hamstring muscles are considered markedly short when they lack 40 degrees of full range-of-active knee extension. A patient with this condition is instructed to sit erect while maintaining a slight contraction of the back extensor muscles with the heel resting on a footstool and the knee extended enough to place a slight but continuous stretch on the hamstrings. This position is maintained for as long as possible, preferably 20 to 30 minutes, and repeated at least six times throughout the day. The goals of these therapeutic exercises are to (1) shorten the elongated back extensor muscles, (2) stretch the shortened hamstring muscles, and (3) prevent compensatory lumbar flexion, which contributes to the lengthening of the back extensors. The presence of compensatory motion can interfere with maintaining the length of the hamstring muscles.

Case Presentation 4

History.: A 34-year-old male distance runner who averages 50 to 60 miles per week is referred to physical therapy for treatment of low back pain. He works as a salesman, which requires that he spend most of his day driving to meet various clients. His low back pain has increased during the day, but he does not have pain when running.

Symptoms.: The examination indicates a flat lumbar spine in standing. During forward bending, marked lumbar flexion is observed, during which the end range of lumbar flexion is 30 degrees and the end range of hip flexion is 65 degrees. His hamstring muscles are short, supported by the finding that his hips flex only 60 degrees during straight-leg raising. When driving, he sits with his lumbar spine in a flexed position. He drives with his car seat pushed as far back as possible, which requires maximum knee extension. Because of the shortness of his hamstring muscles, his hip flexion is only 65 degrees and thus his lumbar spine is forced into a flexed position.

Muscle Length and Strength.: The patient is instructed in a program of hamstring muscle stretching that requires him to sit in a straight-back chair with his hips positioned at 90 degrees and his heel placed on a foot stool that places a slight but continuous stretch on his hamstring muscles. He is asked to maintain this position for as long as possible. He is also instructed to perform isometric back extension by pushing his thoracic spine against the chair back for ten repetitions at least five to six times a day while actively extending his knee. The patient is also instructed to move his car seat forward so that he does not have to maximally extend his knee, allowing him to sit with his hips at a 90-degree angle.

Outcome.: His back pain subsides as soon as he avoids the position of lumbar flexion. Over a period of 4 weeks the range of his straight-leg raise improves 10 degrees, and during standing forward bending he no longer demonstrates excessive lumbar flexion. The patient has learned to limit his lumbar motion to the point of reversing the lumbar curve but not allowing his lumbar spine to go into excessive flexion.

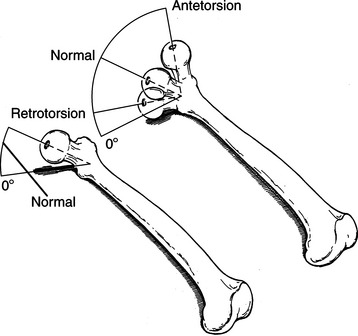

Dissociated Length Changes in Synergistic Muscles

Traditionally, synergistic muscles that perform a specific joint motion are thought to undergo similar structural changes in length, but careful testing often indicates that this is not necessarily the case. For example, not all the hip flexors are shortened when there is a limitation of hip extension. Typically, the length of the hamstring muscles is tested as a group by examining the degree of hip flexion during the straight-leg raise.32 However, the different hip flexors and hamstring muscles contribute to movements other than flexion or extension. Consequently, one of the muscles can become shortened, whereas one of its synergists can retain its normal length or become lengthened. The most common compensatory movement direction is into rotation. In the case of the hip flexors, abduction is also a compensatory movement direction.

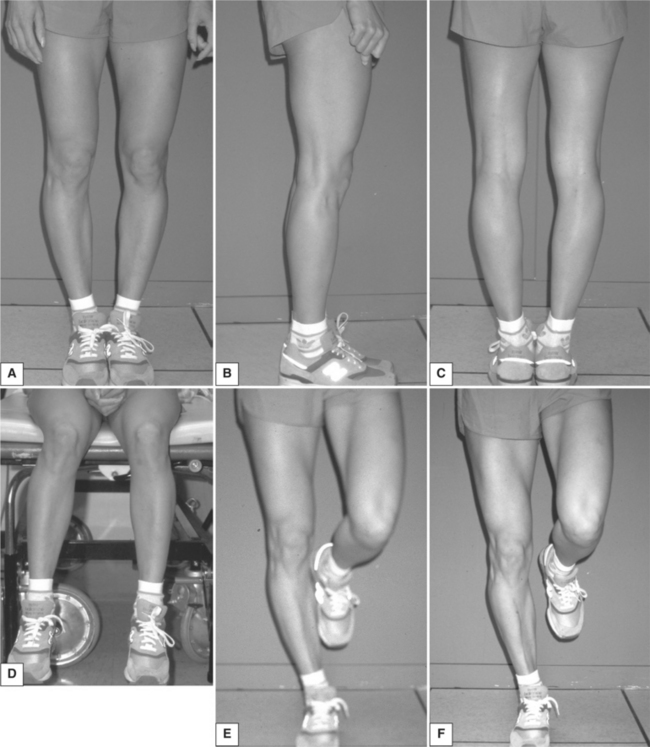

When testing hip flexor length, the hip is allowed to abduct or rotate medially at the limit of the excursion into hip extension, which then permits the hip to extend another 10 degrees, the shortened muscle is the TFL, not the iliopsoas muscle. In fact, specific testing of hip flexor length often indicates that the iliopsoas muscle is lengthened when the TFL is shortened. Similarly, when testing the length of the hamstring muscles, if care is taken to prevent hip medial rotation while in the sitting position (the hip joint is flexed to 80 degrees), the terminal knee position is 15 degrees of flexion. If the hip is allowed to rotate medially and the knee flexion decreases, it is an indication that the medial hamstring muscles, not the lateral hamstring muscles, are shortened (Figure 2-18). Table 2-1 illustrates examples of common length imbalances in synergistic muscles.

Table 2-1

Length Imbalances in Synergistic Muscles

| MUSCLE MOVEMENT | SHORT MUSCLE | LONG MUSCLE |

| Scapular elevators and adductors | Levator scapulae | Upper trapezius |

| Scapular adductors | Rhomboids | Lower trapezius |

| Glenohumeral medial rotators | Pectoralis major | Subscapularis |

| Trunk flexors that tilt the pelvis in a posterior direction | Rectus abdominis | External oblique abdominal |

| Hip flexors | TFL | Iliopsoas |

| Hip abductors | TFL | Posterior gluteus medius |

| Hip extensors and knee flexors | Medial hamstrings | Lateral hamstrings |

| Ankle dorsiflexors | Extensor digitorum longus | Tibialis anterior |

Figure 2-18 A, Sitting position with a resting alignment of hip medial rotation. B, During knee extension, the degree of hip medial rotation increases. C, Laterally rotated hip and decreased knee extension.

The difference in the length of two synergistic muscles is a contributing factor to compensatory motion and the development of movement impairment syndromes. Most often the compensatory motion is into rotation. Care in assessing the muscle length, examining the postural alignment, and observing the specific motion of the joints controlled by the muscle are necessary to identify the dissociated length change impairments of synergistic muscles.

Muscle and Soft-Tissue Stiffness

Stiffness, which is defined as the change in tension per unit of change in length,59 is discussed because this characteristic of muscle and other soft tissues is believed to be a major contributor to movement patterns and movement impairment syndromes. When passive motion of a joint is assessed, all the tissues crossing the joint contribute to the resistance, which can be referred to as joint stiffness. When the range of motion of a joint is limited, it is also described as stiff. In this text, limited range of motion is not considered as a problem of stiffness.

Another concept of stiffness is the tension developed by a combination of active contraction and passive resistance. A variety of studies6,8,22,69 have examined stiffness under both passive and active conditions. Under active conditions, stiffness refers to the total tension developed when muscles are stretched when actively contracting. For the purposes of this text, stiffness refers to the resistance present during the passive elongation of muscle and connective tissue, not during active muscle contraction or at the end of the range of motion. Stiffness, as discussed in this text, is primarily attributed to muscle, because the assessment is made during examinations of muscle length.

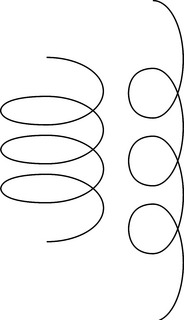

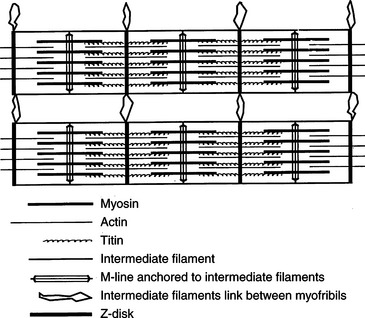

Stiffness is a characteristic of muscles, and muscles have been described as having properties that are similar to springs.6,11,69 Thus the resistance that is felt when a muscle is passively elongated can be considered analogous to the resistance associated with elongating a spring (Figure 2-19). Components of muscle, which have been identified as contributing to the resistance to stretching, are the extracellular and intracellular series elastic structures. The current information suggests that the primary contributor to intracellular resistance to passive stretching is titin, a large connective tissue protein34,68 (Figure 2-20). To a lesser extent, the weak binding of the cross bridges of the myosin filaments contribute to intracellular resistance.54 There are six titin proteins for each myosin filament. Therefore increasing the number of myosin filaments affects the stiffness of the muscle because of the concomitant increase in the number of titin proteins.

Figure 2-20 Picture from skeletal muscle APTA. (From Friden J, Lieber RL: The structural and mechanical basis of exercise-induced muscle injury, Med Sci Sports Exerc 24:521, 1992.)

Another contribution to muscle stiffness is thixotropy, which is the property of a substance that, when static for a period of time, becomes stiff and resists flow. It is defined as the property of various gels that become fluid when disturbed (i.e., by shaking).42 Thixotropy is attributed to weak binding of the cross bridges, and it is considered a source of resistance to passive stretching but a minor contributor to the total passive resistance.

Hypertrophy is known to increase the number of contractile proteins and connective tissue proteins.4 The increase in these proteins suggests a concurrent increase in the stiffness of the muscle because of both increased connective tissue proteins, such as titin, and increased contractile elements. Chleboun and colleagues have shown that the cross-sectional area of muscle is correlated with the stiffness of the muscle through the range as it is elongated, rather than at the end of its range.9 Conversely, atrophy or loss of contractile elements decreases the through-the-range stiffness because of the reduction in both connective tissue proteins and the number of cross bridges.

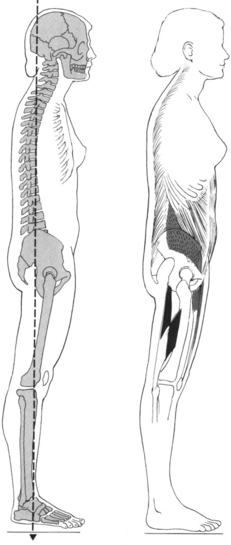

Variation in the stiffness of muscles and joints can be a factor in the development of compensatory motion in contiguous joints and can contribute to musculoskeletal pain syndromes. For example, in the sitting position when the hamstring muscles are placed on stretch, the lumbar spine will flex to a greater range than when the hamstring muscles are not stretched as much. During forward bending this increased lumbar flexion range is not evident. The rate of forward bending is not examined in this study.66 Thomas demonstrates that during the forward reach test, typically men will bend their lumbar spine, whereas women will flex their hips during the initial phase.63 Men generally have shorter and stiffer hamstring muscles than women. This fact is consistent with the hypothesis that flexible tissues stretch more readily than less flexible tissues. The passive stiffness of the hamstring muscles is found to be significantly greater in the patient with low back pain than in control subjects.61 The length of the hamstring muscles is not found to be significantly different between the two groups. These investigators did not suggest a possible explanation for this finding.

This text hypothesizes that motion occurs earlier at the joint with the lesser degree of stiffness, in this case the lumbar spine, rather than at the stiffer joint, which in this case is the hip joint. This does not mean that the range of lumbar spine motion is greater when the hamstring muscles are taut. It suggests that motion will occur earlier at the more flexible segment in situations where motion involves both joints. During forward bending, the demands for maximum motion will cause the joint to move through its full range of motion. A possible long-term consequence, if this movement pattern is continually repeated, is that the flexibility of the lumbar spine will increase, predisposing the spine to move into flexion whenever flexion should be occurring at the hip joint.

When joints with common movement directions are in series and one of the joints is more flexible than the others, the flexible joint is particularly susceptible to movement. When movement occurs at this joint when it should remain stable, it is called compensatory relative flexibility, a phenomenon that is discussed later. This concept is best understood if the multiple segments of the human body are believed to be controlled by a series of springs. The muscles of the body are similar to a series of springs of differing extensibility, and the intersegmental differences in the extensibility of these springs contribute to compensatory motions, particularly of the spine.

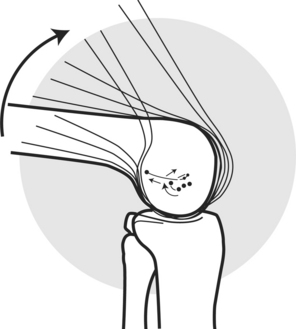

Compensatory Relative Flexibility

Clinical observations.: Hypertrophy increases the stiffness of muscles through the range of motion.9 Because of the intersegmental variations in the springlike behavior of muscles, a reasonable hypothesis is that increased stiffness of one muscle group can cause compensatory movement at an adjoining joint that is controlled by muscles or joints with less stiffness. A common clinical observation is that when passively testing the length of a muscle, movement of a contiguous joint occurs long before the muscle is fully elongated. The movement of the contiguous joint is a compensatory motion. For example, if the lumbar spine is particularly flexible in the extension direction and the latissimus dorsi muscle is relatively stiffer, the lumbar spine will extend when the patient performs shoulder flexion, even before reaching the end of the length of the latissimus dorsi muscle.

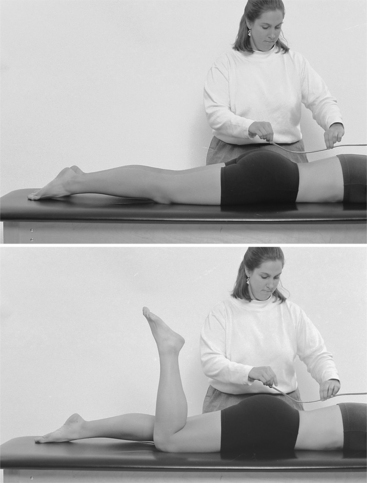

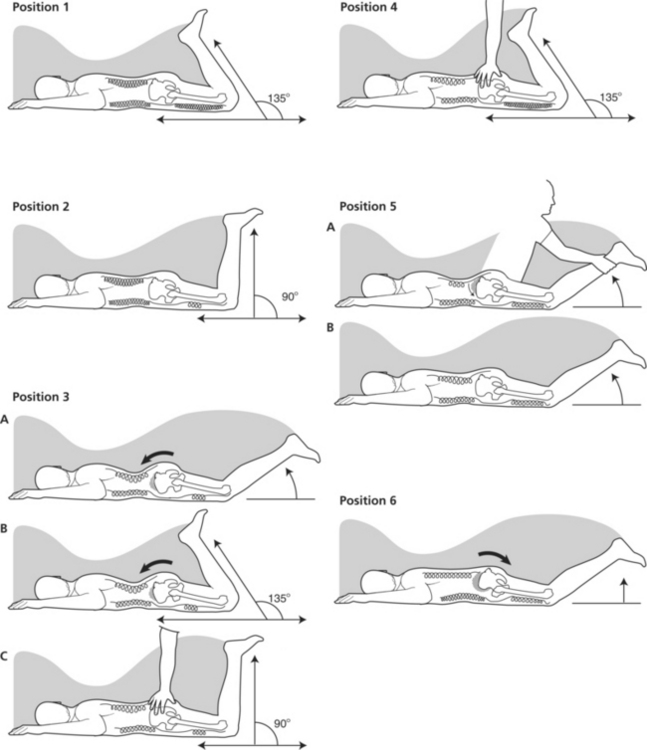

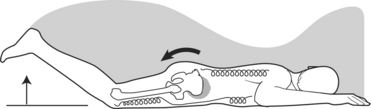

Under optimal conditions when the therapist passively flexes the knee with the patient lying prone, which stretches the rectus femoris muscle, there should not be movement of the pelvis and spine except possibly near the end of the knee flexion range of 115 to 125 degrees. If movement of the pelvis and spine occurs between 45 and 115 degrees of knee flexion, it may be that segments of the spine are more flexible than the rectus femoris muscle is extensible. As discussed later, this phenomenon does not necessarily mean that the rectus femoris muscle is short; but it implies that it is stiffer than the support provided to the pelvis and spine and therefore the stiffness produces lumbar extension.

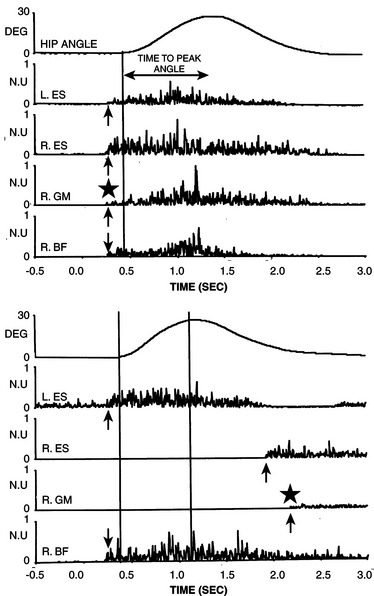

When a patient performs active knee flexion, there are automatic stabilizing responses that can affect the movement of the pelvis and spine. For example, during active knee flexion in the prone position, the contraction of the hamstring muscles will tilt the pelvis posteriorly. However, to stabilize and limit the movement of the pelvis, the hip flexors and back extensor muscles should contract. This stabilizing action of the muscles can either be excessive or insufficient. (Alterations of this stabilization pattern are discussed under the section on motor control impairments.) The examples given in Figure 2-21 demonstrate different combinations of muscle stiffness and length impairments and their role in compensatory movements of the pelvis and spine.

Figure 2-21 Variations in lumbopelvic motion during knee flexion associated with differences in the stiffness of the abdominal and rectus femoris muscles. In the starting position of hip and knee extension, the pelvis and lumbar spine are in the same correct alignment as in position 1.

The pelvis and lumbar spine are in the same correct alignment in the starting position. During either active and passive knee flexions, the following observations can be made:

1. Normal length of the rectus femoris muscle. The knee is flexed without lumbopelvic movement.

2. Short rectus femoris. Without lumbopelvic compensation, the knee is flexed without movement of the pelvis or lumbar spine, but knee flexion stops at 90 degrees, indicating short quadriceps muscles.

3. Stiff and short rectus femoris muscle with lumbopelvic compensation. The knee is flexed and the pelvis tilts anteriorly. The lumbar extension increases at 60 degrees of knee flexion, but the knee flexes to 135 degrees. When the therapist stabilizes the pelvis, the knee flexion stops at 90 degrees.

4. Stiffness, not shortness, of rectus femoris muscle with lumbopelvic compensation. The knee is flexed and the pelvis is tilted anteriorly. The lumbar extension increases at 60 degrees of knee flexion, but the knee is flexed to 135 degrees. When the therapist stabilizes the pelvis, the knee still flexes to 135 degrees.

5. Stiffness of rectus femoris muscle with automatic lumbopelvic stabilization. During passive motion, but not active knee flexion, the compensatory lumbar extension motion is observed.

6. Deficient lumbopelvic counter stabilization. At the initiation of knee flexion, the pelvis is tilted posteriorly and the lumbar spine slightly reduces its curve.

Explanation of Figure 2-21

1. Optimal balance of muscle stiffness and joint stability. The rectus femoris muscle is stretched without compensatory lumbopelvic motion. Therefore the stiffness of the anterior supporting structures of the spine and the passive stiffness of the abdominal muscles are greater than or equal to the stiffness of the rectus femoris muscle.

2. Shortness of rectus femoris muscle with counterbalancing stiffness of spinal structures and abdominal muscles. Because the knee flexes to only 90 degrees, the rectus femoris muscle is short and the muscle excursion does not reach the expected standard. However, lumbopelvic compensatory motion is not evident even though the rectus femoris muscle is short. It is not stiffer than the anterior supporting structures of the lumbar spine and the passive extensibility of the abdominal muscles.