HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

The year 2008 sees the 150th anniversary of the publication of Gray’s Anatomy. The book is a rarity in textbook publishing in having been in continuous publication on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, for so long. One and a half centuries is an exceptionally long era for a textbook, and of course the volume published now is very different from the one Mr. Henry Gray first created with his colleague Dr Henry Vandyke Carter, in mid-Victorian London. In this introductory essay, I shall explain the long history of Gray’s, from those Victorian days right up to today.

The shortcomings of existing anatomical textbooks probably impressed themselves upon Henry Gray when he was still a student at St George’s Hospital Medical School, near London’s Hyde Park Corner, in the early 1840s. He began thinking about creating a new anatomy textbook a decade later, while war was being fought in the Crimea. New legislation was being planned which would establish the General Medical Council (1858) to regulate professional education and standards.

Gray was twenty-eight years old, and a teacher himself at St George’s. He was very able, hard-working, and highly ambitious, already a Fellow of the Royal Society, and of the Royal College of Surgeons. Although little is known about his personal life, his was a glittering career thus far, achieved while he served and taught on the hospital wards and in the dissecting room (Fig. 1). (1)

Fig. 1 Henry Gray (1827–1861) is shown here in the foreground, seated by the feet of the cadaver. The photograph was taken by a medical student, Joseph Langhorn. The room is the dissecting room of St George’s Hospital medical school in Kinnerton Street, London. Gray is shown surrounded by staff and students. When the photo was taken, on 27th March 1860, Carter had left St George’s, to become Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Grant Medical College, in Bombay (nowadays Mumbai). The second edition of Gray’s Anatomy was in its proof stages, to appear in December 1860. Gray died just over a year later, in June 1861, at the height of his powers.

Gray shared the idea for the new book with a talented colleague on the teaching staff at St George’s, Henry Vandyke Carter, in November 1855. Carter was from a family of Scarborough artists, and was himself a clever artist and microscopist. He had produced fine illustrations for Gray’s scientific publications before, but could see that this idea was a much more complex kind of a project. Carter recorded in his diary:

Little to record. Gray made proposal to assist by drawings in bringing out a Manual for students: a good idea but did not come to any plan … too exacting, for would not be a simple artist. (2)

Neither of these young men was interested in producing a pretty book, or an expensive one. Their purpose was to supply an affordable, accurate teaching aid for people like their own students, who might soon be required to operate on real patients, or on soldiers injured at Sebastopol or some other battlefield. The book they planned together was a practical one, designed to encourage youngsters to study anatomy, help them pass exams, and assist them as budding surgeons. It was not simply an anatomy textbook, but a guide to dissecting procedure, and to the major operations.

Gray and Carter belonged to a generation of anatomists ready to infuse the study of human anatomy with a new, and respectable, scientificity. Disreputable aspects of the profession’s history, acquired during the days of bodysnatching, were assiduously being forgotten. The Anatomy Act of 1832 had legalized the requisition of unclaimed bodies from workhouse and hospital mortuaries, and the study of anatomy (now with its own Inspectorate) was rising in respectability in Britain. The private anatomy schools which had flourished in the Regency period were closing their doors, and the major teaching hospitals were erecting new purpose-built dissection rooms. (3)

The best-known student works when Gray and Carter had qualified were probably Erasmus Wilson’s Anatomist’s Vade Mecum, and Elements of Anatomy by Jones Quain. Both works were small – pocket-sized – but Quain came in two thick volumes. Both Quain’s and Wilson’s works were good books in their way, but their small pages of dense type, and even smaller illustrations, were somewhat daunting, seeming to demand much nose-to-the-grindstone effort from the reader.

The planned new textbook’s dimensions and character were serious matters. Pocket manuals were commercially successful because they appealed to students by offering much knowledge in a small compass. But pocket-sized books had button-sized illustrations. Knox’s Manual of Human Anatomy, for example, was a good book, but was only six inches by four (17 × 10 cm) and few of its illustrations occupied more than a third of a page. Gray and Carter must have discussed this matter between themselves, and with Gray’s publisher JW Parker & Son, before decisions were taken about the size and girth of the new book, and especially the size of its illustrations.

The two men were earnestly engaged for the following eighteen months in the work which formed the basis of the book. All the dissections were undertaken jointly, Gray wrote the text, and Carter the illustrations. While Gray and Carter were working, a new edition of Quain’s was published: this time it was a ‘triple-decker’ – in three volumes – of 1740 pages in all. Gray and Carter’s working days were long, all the hours of daylight, eight or nine hours at a stretch – right through 1856, and well into 1857. We can infer from the warmth of Gray’s appreciation of Carter in his published acknowledgements that their collaboration was a happy one.

The Author gratefully acknowledges the great services he has derived in the execution of this work, from the assistance of his friend, Dr. H. V. Carter, late Demonstrator of Anatomy at St George’s Hospital. All the drawings from which the engravings were made, were executed by him. (4)

With all the dissections done, and Carter’s inscribed wood-blocks at the engravers, Gray took six months’ leave from his teaching at St George’s to work as a personal doctor for a wealthy family. It was probably as good a way as any to get a well-earned break from the dissecting room and the dead-house. (5)

Carter sat the examination for medical officers in the East India Company, and sailed for India in the spring of 1858, when the book was still in its proof stages. Gray had left a trusted colleague, Timothy Holmes, to see the book through the press.

Gray looked over the final galley proofs, just before the book finally went to press. Timothy Holmes’s association with the book’s first edition would later prove vital to its survival.

THE FIRST EDITION

The book Gray and Carter had created together, Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical appeared at the very end of August 1858, to immediate acclaim. Reviews in the Lancet and British Medical Journal were highly complimentary, and students flocked to buy.

It is not difficult to understand why it was a runaway success. Gray’s Anatomy knocked its competitors into a cocked hat. The book holds well in the hand, it feels substantial, and it contains everything required. It was considerably smaller and more slender than the doorstopper with which modern readers are familiar. To contemporaries it was small enough to be portable, but large enough for decent illustrations: ‘royal octavo’ – nine-and-a-half inches by six (24 × 15 cm) – about two-thirds of modern A4 size. Its medium size, single volume format was far removed from Quain, yet double the size of Knox’s Manual.

Simply organized and well designed, the book explains itself confidently and well: the clarity and authority of the prose is manifest. But what made it unique for its day was the outstanding size and quality of the illustrations. Gray thanked the wood engravers Butterworth and Heath for the ‘great care and fidelity’ they had displayed in the engravings, but it was really to Carter that the book owed its extraordinary success.

The beauty of Carter’s illustrations resides in their diagrammatic clarity, quite atypical for their time. The images in contemporary anatomy books were usually proxy labelled: dotted with tiny numbers or letters (often hard to find, or read) or bristling with a sheaf of numbered arrows, referring to a key situated elsewhere, usually in a footnote which was sometimes so lengthy it wrapped round onto the following page. Proxy labels require the reader’s eye to move to and fro: from the structure to the proxy label to the legend and back again. There was plenty of scope for slippage, annoyance and distraction. Carter’s illustrations, by contrast, unify name and structure, enabling the eye to assimilate both at a glance. We are so familiar with Carter’s images that it is hard to appreciate how incredibly modern they must have seemed in 1858. The volume made human anatomy look new, exciting, accessible, and do-able.

The first edition was covered in a light brown bookbinder’s cloth embossed all over in a dotted pattern, and a double picture-frame border. Its spine was lettered in gold blocking:

GRAY’S ANATOMY

with ‘DESCRIPTIVE AND SURGICAL’ in small capitals underneath. Gray’s Anatomy is how it has been referred to ever since. Carter was given credit with Gray on the book’s titlepage for undertaking all the dissections on which the book was based, and sole credit for all the illustrations, though his name appeared in a significantly smaller type, and for some obscure reason he was described as the ‘Late Demonstrator in Anatomy at St George’s Hospital’ rather than being given his full current title, which was Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Grant Medical College, Bombay. Perhaps Gray was concerned not be upstaged, as he was still only a Lecturer at St George’s. Gray may have been aware that his words had been upstaged by the quality of Carter’s anatomical images. He need not have worried: Gray is the famous name on the spine of the book.

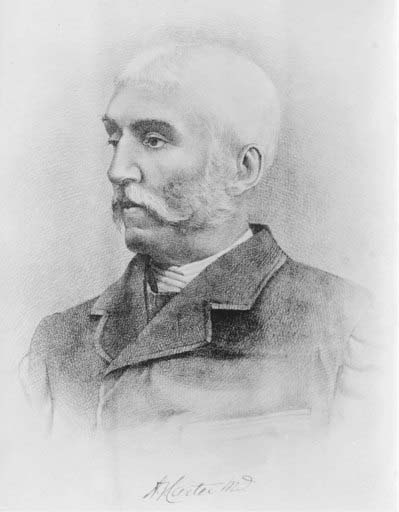

Gray was paid £150 for every thousand copies sold. Carter never received a royalty payment, just a one-off fee at publication, which may have allowed him to purchase the long-wished for microscope he took with him to India (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Henry Vandyke Carter (1831–1897). Carter was appointed Honorary Surgeon to the Queen in 1890.

The first edition print-run of 2000 copies sold out swiftly. A parallel edition was published in the United States in 1859, and Gray must have been deeply gratified to have to revise an enlarged new English edition in 1859–60, though he was surely saddened and worried by the death of John Parker junior, at the young age of 40, while the book was going through the press. The second edition came out in the December of 1860 and it too sold like hot cakes, as indeed has every subsequent edition.

The following summer, in June 1861, at the height of his powers and full of promise, Henry Gray died unexpectedly at the age of only 34. Gray had contracted smallpox while nursing his little nephew Charles. A new strain of the disease was more virulent than the one with which Gray had been vaccinated as a child: the disease became confluent, and Gray died in a matter of days.

Within months the whole country would be pitched into the mourning for the death of Prince Albert and the creative era over which he had presided – especially the decade which had flowered since the Great Exhibition of 1851 – would be history.

THE BOOK SURVIVES

Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical could have died too. With Carter in India, the death of Gray, so swiftly after the younger Parker, might have spelled catastrophe. Certainly, at St George’s there was a sense of calamity. The grand old medical man Sir Benjamin Brodie, Sergeant-Surgeon to the Queen, and the great supporter of Gray to whom Anatomy had been dedicated, cried forlornly: ‘Who is there to take his place?’ (1)

But old J.W. Parker ensured the survival of Gray’s by inviting Timothy Holmes, the doctor who had helped proof-read the first edition, and who had filled Gray’s shoes at the medical school, to serve as Editor for the next edition. Other long-running anatomy works such as Quain, remained in print in a similar way, co-edited by other hands. (6)

Holmes (1825–1907) was another gifted George’s man, a scholarship boy who had won an exhibition to Cambridge, where his brilliance was recognized. Holmes was a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons at 28. John Parker junior had commissioned him to edit A System of Surgery (1860–64), an important essay series by distinguished surgeons on subjects of their own choosing. Many of Holmes’s authors remain important figures, even today: John Simon, James Paget, Henry Gray, Ernest Hart, Jonathan Hutchinson, Brown Séquard, and Joseph Lister. Holmes had lost an eye in an operative accident, and he had a gruff manner which terrified students, yet he published a lament for young Parker which reveals him capable of deep feeling. (7)

John Parker senior’s heart, however, was no longer in publishing. His son’s death had closed down the future for him. The business, with all its stocks and copyrights, was sold to Messrs Longman. Parker retired to the village of Farnham, where he later died.

With Holmes as editor, and Longmans as publisher, the immediate future of Gray’s Anatomy was assured. The third edition appeared in 1864 with relatively few changes, Gray’s estate receiving the balance of his royalty after Holmes was paid £100 for his work.

THE MISSING OBITUARY

Why no obituary appeared for Henry Gray in Gray’s Anatomy is curious. Gray had referred to Holmes as his ‘friend’ in the preface to the first edition, yet it would also be true to say that they were rivals. Both had just applied for a vacant post at St George’s, as Assistant Surgeon. Had Gray lived, it is thought that Holmes may not have been appointed, despite his seniority in age. (1)

Later commentators have suggested, as though from inside knowledge, that Holmes’s ‘proof-reading’ included improving Gray’s writing style. This could be a reflection of Holmes’s own self-regard, but there may be some truth in it. There can be no doubt that as Editor of seven subsequent editions of Gray’s Anatomy (3rd to 9th editions, 1863 – 1880) Holmes added new material, and had to correct and compress passages, but it is also possible that back in 1857, Gray’s original manuscript had been left in a poor state for Holmes to sort out. In other works, Gray’s writing style was lucid, but he always seems to have paid a copyist to transcribe his work prior to submission. The original manuscript of Gray’s Anatomy, sadly, has not survived, so it is impossible to be sure how much of the finished version had actually been written by Holmes.

It may be that Gray’s glittering career, or perhaps the patronage which unquestionably advanced it, created jealousies among his colleagues, or that there was something in Gray’s manner which precluded affection, or which created resentments among clever social inferiors like Carter and Holmes, especially if they felt their contributions to his brilliant career were not given adequate credit. Whatever the explanation, no reference to Gray’s life or death appeared in Gray’s Anatomy itself until the twentieth century. (8)

A SUCCESSION OF EDITORS

Holmes expanded areas of the book that Gray himself had developed in the 2nd edition (1860), notably in ‘general’ anatomy (histology) and ‘development’ (embryology). In Holmes’s time as editor the volume grew from 788 pages in 1864 to 960 in 1880 (9th edition), with the histological section paginated separately in roman numerals at the front of the book. Extra illustrations were added, mainly from other published sources.

The connections with Gray and Carter, and with St George’s were maintained with the appointment of the next editor, T. Pickering Pick, who had been a student at St George’s in Gray’s time. From 1883 (10th edition) onwards, Pick kept up with current research, rewrote and integrated the histology and embryology into the volume, dropped Holmes from the titlepage, removed Gray’s preface to the first edition, and added emboldened subheadings which certainly improved the appearance and accessibility of the text. Pick said he had ‘tried to keep before himself the fact that the work is intended for students of anatomy rather than for the Scientific Anatomist’ (13th edition 1893).

Pick also introduced colour printing (in 1887, 11th edition) and experimented with the addition of illustrations using the new printing method of half-tone dots: for colour (which worked) and for new black-and-white illustrations (which didn’t). Half-tone shades of grey compared poorly with Carter’s wood engravings, still sharp and clear by comparison.

What Henry Vandyke Carter made of these changes is a rich topic for speculation. He returned to England in 1888, having retired from the Indian Medical Service, full of honours – Deputy Surgeon General, and in 1890, was made Honorary Surgeon to Queen Victoria. Carter had continued researching throughout his clinical medical career in India, and became one of India’s foremost bacteriologists/tropical disease specialists before there was really a name for either discipline. Carter made some important discoveries, including the fungal cause of mycetoma, which he described and named. He was also a key figure in confirming scientifically in India some major international discoveries, such as Hansen’s discovery of the cause of leprosy, Koch’s discovery of the organism causing tuberculosis, and Laveran’s discovery of the organism which causes malaria. Carter married late in life, and had two young children when he died in Scarborough in 1897, aged 65. Like Gray, he received no obituary in the book.

When Pick was joined on the titlepage by Robert Howden (a professional anatomist from the University of Durham) in 1901 (15th edition), the volume was still easily recognizable as the book Gray and Carter had created. Although many of Carter’s illustrations had been revised or replaced, many others still remained. Sadly, though, an entire section (embryology) was again separately paginated, as its revision had taken longer than anticipated. Gray’s had grown, seemingly inexorably, and was now quite thick and heavy, 1244 pages weighing 5lb8oz/2.5 kg. Both co-editors, and perhaps also its publisher, were dissatisfied with it.

KEY EDITION: 1905

Serious decisions were taken well in advance of the next edition, which turned out to be Pick’s last with Howden. Published 50 years after Gray had first suggested the idea to Carter, the 1905 (16th) edition was a landmark edition.

The period 1880–1930 was a difficult time for anatomical illustration, because the new techniques of photo-lithography and half-tone were not as yet perfected, and in any case could not provide the bold simplicity of line required for a book like Gray’s which depended so heavily on clear illustration, and clear lettering. Recognizing the inferiority of half-tone illustrations by comparison with Carter’s wood engraved originals, Pick and Howden courageously decided to jettison the second-rate half-tones altogether. Most of the next edition’s illustrations were either Carter’s, or old supplementary illustrations inspired by his work, or newly commissioned wood engravings or line drawings, intended ‘to harmonize with Carter’s original figures’. They successfully emulated Carter’s verve. Having fewer pages and lighter paper, the 1905 (16th edition) weighed less than its predecessor, at 4lb11oz/2.1 kg. Typographically, the new edition was superb.

Howden took over as sole editor in 1909 (17th edition) and immediately stamped his personality on Gray’s. He excised ‘Surgical’ from the title, changing it to Anatomy Descriptive and Applied, and removed Carter’s name altogether. He also instigated the beginnings of an editorial board of experts for Gray’s, by adding to the titlepage: ‘Notes on Applied Anatomy’ by AJ Jex-Blake and W Fedde Fedden, both St George’s men. For the first time, the number of illustrations exceeded one thousand. Howden was responsible for the significant innovation of a short historical note on Henry Gray himself, nearly 60 years after his death, which included a portrait photograph (1918, 20th edition).

THE NOMENCLATURE CONTROVERSY

Howden’s era, and that of his successor TB Johnston (of Guy’s) was overshadowed by a cloud of international controversy concerning anatomical terminology. European anatomists were endeavouring to standardize anatomical terms, often using Latinate constructions, a move resisted in Britain and the United States. Gray’s became mired in these debates for over twenty years. The endeavour to be fair to all sides by using multiple terms doubtless generated much confusion amongst students, until a working compromise was at last arrived at in 1955 (32nd edition, 1958).

Johnston oversaw the second re-titling of the book (in 1938, 27th edition): it was now, officially, Gray’s Anatomy, finally ending the fiction that it had ever been known as anything else. Gray’s suffered from paper shortages and printing difficulties in World War II, but successive editions nevertheless continued to grow in size and weight, while illustrations were replaced and added as the text was revised. Between Howden’s first sole effort (1909, 17th edition) to Johnston’s last edition (1958, 32nd edition) Gray’s expanded by over 300 pages – from 1296 to 1604 pages, and almost 300 additional illustrations brought the total to over 1300. Johnston also introduced X-ray plates (1938) and in 1958 (32nd edition) electron micrographs by AS Fitton-Jackson, one of the first occasions on which a woman was credited with a contribution to Gray’s. Johnston felt compelled to mention that she was ‘a blood relative of Henry Gray himself’, perhaps by way of mitigation.

AFTER WORLD WAR II

The editions of Gray’s issued in the decades immediately following the Second World War give the impression of intellectual stagnation. Steady expansion continued in an almost formulaic fashion, with the insertion of additional detail.

The central historical importance of innovation in the success of Gray’s seems to have been lost sight of by its publishers and editors – Johnston (1930–58, 24th to 32nd editions); J Whillis (co-editor with Johnston 1938–54) DV Davies (1958–1967, 32nd to 34th editions) and F Davies (co-editor with DV Davies 1958–64, 32nd to 33rd editions). Gray’s had become so pre-eminent that perhaps complacency crept in, or editors were too daunted or too busy to confront the ‘massive undertaking’ of a root and branch revision. (9) The unexpected deaths of three major figures associated with Gray’s in this era, James Whillis, Francis Davies, and David Vaughan Davies – all of whom had been groomed to take the editorial reins – may have contributed to retard the process. The work became somewhat dull.

KEY EDITION: 1973

DV Davies had recognized the need for modernization, but his unexpected death left the work to other hands. Two Professors of Anatomy at Guy’s, Roger Warwick and Peter Williams, the latter of whom had been involved as an indexer for Gray’s for several years, regarded it as an honour to fulfill Davies’ intentions.

Their 35th edition of 1973 was a significant departure from tradition. Over 780 pages (of 1471) were newly written, almost a third of the illustrations were newly commissioned, and the illustration captions were freshly written throughout. With a complete retypesetting of the text in larger double-column pages, a new index, and the innovation of a bibliography, this edition of Gray’s looked and felt quite unlike its 1967 (34th edition) predecessor, and much more like its modern incarnation.

This 1973 edition departed from earlier volumes in other significant ways. The editors made explicit their intention to try to counter the impetus towards specialization and compartmentalization in twentieth century medicine, by embracing and attempting to reintegrate the complexity of the available knowledge. Warwick and Williams openly renounced the pose of omniscience adopted by many textbooks, believing it important to accept and mention areas of ignorance or uncertainty. They shared with the reader the difficulty of keeping abreast in the sea of research, and accepted with a refreshing humility the impossibility of fulfilling their own ambitious programme.

Warwick and Williams’ 1973 edition had much in common with Gray and Carter’s first edition. It was bold and innovative: respectful of its heritage, while also striking out into new territory. It was visually attractive and visually informative. It embodied a sense of a treasury of information laid out for the reader. (10) It was published simultaneously in the United States (the American Gray’s had developed a distinct character of its own in the interval), and sold extremely well there. (10)

The influence of the Warwick and Williams’s edition was forceful and long-lasting, and set a new pattern for the following quarter century. As has transpired several times before, wittingly or unwittingly a new editor was being prepared for the future: Dr Susan Standring (of Guy’s) who created the new bibliography for the 1973 edition of Gray’s, went on to serve on the editorial board, and has served as Editor-in-Chief for the last two editions (2004–2008, 39th and 40th editions). Both editions are important for different reasons.

For the 39th edition, the entire content of Gray’s was reorganized, from systematic to regional anatomy. This great sea-change was not just organizational, but historic, because since its outset Gray’s had prioritized bodily systems, with subsidiary emphasis on how the systems interweave in the regions. Professor Standring explained that the change of emphasis to the regions of the body had long been asked for by readers and users of Gray’s, and that new imaging techniques in our era have raised the clinical importance of local anatomy. (11) The change was facilitated by an enormous collective effort on the part of the editorial team and the illustrators.

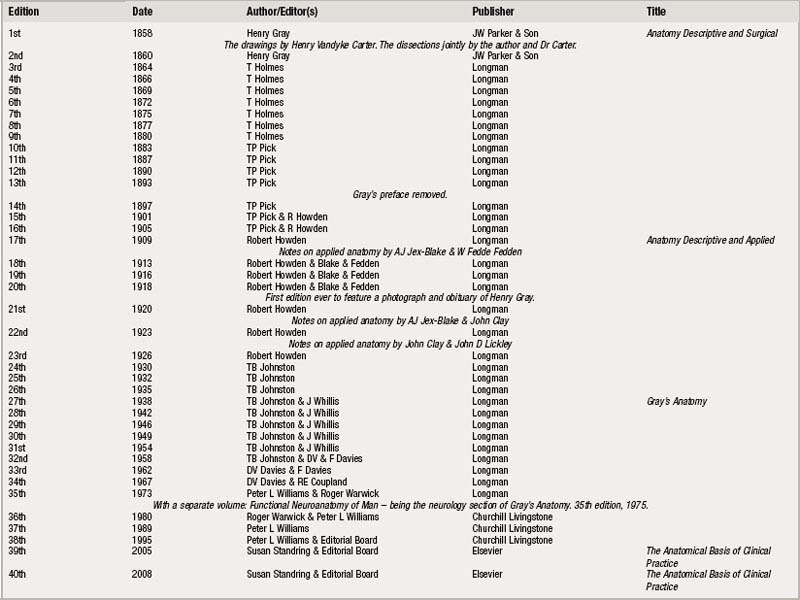

The current edition consolidates that momentous change, and is of historic importance because it is the fortieth edition, published on the 150th anniversary of Gray’s original publication in autumn 1858 (see Table 1).

THE DOCTORS’ BIBLE

Neither Gray nor Carter, young men who – by their committed hard work between 1856 and 1858 – created the original Gray’s Anatomy, would have conceived that years after their deaths their book would not only be a household name, but regarded as a work of such pre-eminent importance that a novelist half a world away would rank it as cardinal – alongside the Bible and Shakespeare – to a doctor’s education. (11)

Now, in this 40th edition of Gray’s Anatomy, we can look back over 150 years of continuous publication to appraise the long term value of their efforts. We can discern how the book they created triumphed over its competitors, and has survived pre-eminent. Gray’s is a remarkable publishing phenomenon. Although the volume now looks quite different to the original, and contains so much more, its kinship with the Gray’s Anatomy of 1858 is easily demonstrable by direct descent, every edition updated by Henry Gray’s successor. Works are rare indeed that have had such a long history of continuous publication on both sides of the Atlantic, and such a useful one.

With this fine new 150th anniversary edition, the book goes marching on.

Ruth Richardson, MA, DPhil, FRHistSoc

Affiliated Scholar in the History & Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge; Senior Visiting Research Fellow in History, University of Hertfordshire at Hatfield.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For their assistance while I was undertaking the research for this essay, I should like to thank the Librarians and Archivists and Staff at the British Library, Society of Apothecaries, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Royal College of Surgeons, Royal Society of Medicine, St Bride Printing Library, St George’s Hospital Tooting, Scarborough City Museum & Art Gallery, University of Reading, Wellcome Institute Library, Westminster City Archives and Windsor Castle; and the following individuals: Anne Bayliss, Gordon Bell, David Buchanan, Dee Cook, Arthur Credland, Chris Hamlin, Victoria Killick, Louise King, Keith Nicol, Sarah Potts, Mark Smalley, Nallini Thevakarrunai. Above all, my thanks to Brian Hurwitz, who has read and advised on the evolving text.

1 Anon. Henry Gray. St George’s Hospital Gazette. 1908;16(4):49-54.

2 Carter HV: Diary. Wellcome Western Manuscript 5818: Nov 25th 1855.

3 Richardson R. Death, Dissection & the Destitute. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2000;193-249. 287, 357.

4 Gray H. Anatomy: Descriptive and Surgical. London: JW Parker & Son, 1858. Preface.

5 Nicol KE. Henry Gray of St George’s Hospital: a Chronology. London: Published by the Author, 2002.

6 Quain J. Sharpey W, Ellis GV. Elements of Anatomy. London: Walton & Maberly, 1856.

7 Holmes T, editor. A System of Surgery. London: JW Parker & Son, 1860. I: Preface.

8 Gray’s Anatomy. London: Longmans, 1918.

9 Tansey EM. A Brief History of Gray’s Anatomy. Gray’s Anatomy. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1995;xvii-xvxx.

10 Gray’s Anatomy. London: Churchill, 1973. preface.

11 Gray’s Anatomy. 39th edition. London: Elsevier; 2005. Preface.

12 Sinclair Lewis 1925: Arrowsmith. Place, Harcourt Brace: 4.