Chapter 6 Admission emergencies

When emergencies occur a well-rehearsed approach facilitates efficient teamwork and ensures that all correct steps are taken. Availability of clear, updated protocols is crucial for immediate management by staff on the labour ward.

Training protocols or drills for staff (doctors, midwives, anaesthetists, paediatricians and theatre assistants) are encouraged for improving performance and outcome in emergencies.

MANAGEMENT OF IMMINENT DELIVERY WITH OR WITHOUT FETAL COMPROMISE

The following procedures should be adopted if delivery is imminent.

SPECIFIC PROBLEMS

Cord presentation or prolapse

Always confirm gestational age before planning any further management.

Cord presentation

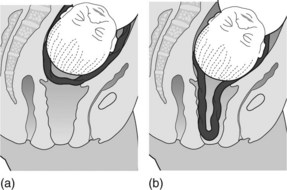

This occurs when the cord is in front of the presenting part of the fetus behind intact membranes. When the membranes are not ruptured, palpate through them with the tip of the fingers to exclude the presence of pulsation due to cord presentation or vasa praevia (Figure 6.1a). The diagnosis can also be made using ultrasound and colour flow Doppler, and is useful in circumstances such as an unstable breech presentation. Variable fetal heart rate decelerations may be evident.

Cord prolapse

Following membrane rupture the cord may prolapse through the cervix, may remain in the vagina or be expelled through the introitus (Figure 6.1b).

Cord prolapse occurs in approximately 0.2% of all births.

Points to remember in management

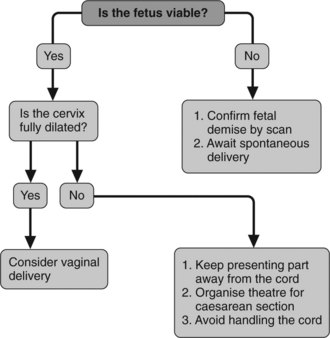

Figure 6.2 presents an algorithm for management of cord prolapse.

Major obstetric haemorrhage

Management

Box 6.1 gives details of blood component therapy.

Box 6.1 Blood component therapy

Antepartum haemorrhage

Important points to remember about vaginal bleeding in pregnancy

General guidelines for management

Note: Modify guidelines for degree of antepartum haemorrhage.

Placental separation (abruption)

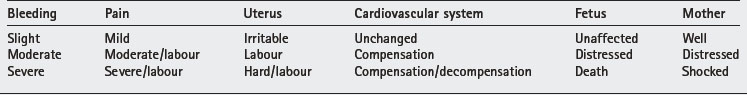

Presentation depends on the amount of bleeding (Table 6.1).

Diagnosis

Management

This is governed by the amount of bleeding, whether bleeding continues, the status both of the mother and fetus, the gestational age of the pregnancy and previous obstetric history.

Placental abruption can occur at any gestational age. Follow the general guidelines of management of antepartum haemorrhage. Placental abruption is usually treated actively by delivery, by caesarean section if the fetus is alive and viable but vaginally if the fetus is dead. Close monitoring throughout labour is essential. Caesarean section might be required if labour is prolonged to decrease the risk of severe coagulopathy.

Severity of bleeding is a useful guide for management.

Mild bleeding

Moderate bleeding

Severe bleeding

Placenta praevia

Grading of placenta praevia

Not clinically useful for predicting severity of antepartum haemorrhage.

Management

Management depends on the gestational age, the amount of blood loss, fetal position and the placental site (in cases of minor placenta praevia).

Box 6.2 Examination in theatre: requirements

For grade I anterior placenta praevia, rupture the membranes and attempt vaginal delivery. Close surveillance is mandatory. All other grades of placenta praevia necessitate caesarean section.

Fits

Pregnancy can aggravate an existing tendency to fits (epilepsy), or convulsions can complicate pre-eclampsia (eclampsia). The presence of hypertension, proteinuria and generalised oedema and past history of epilepsy are important points that need to be considered in this situation. Close monitoring of the woman’s condition, the fetus (by cardiotocography) and laboratory results (e.g. blood count, urea, electrolytes, clotting screen and liver function) are mandatory.

Two-thirds of eclampsia occur before and a third after delivery, sometimes 3 or more days post partum (12%). Eclampsia is associated with up to 14% direct maternal deaths in the UK (Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 2004).

Eclampsia

Prevention and anticipation are important measures. Note symptoms (hyper-reflexion, clonus, headaches, photophobia, epigastric pain, flashing lights) elevated transaminases, creatinine, urea, proteinuria (>1 g/24 h or 3 plus) platelets below 100 × 109/l or prolonged clotting times.

Guidelines for management

Magnesium sulphate

Fluid balance

Antihypertensives (see Box 6.3 and Box 6.4)

A blood pressure of 160 mmHg systolic over 110 mgHg diastolic requires urgent treatment to prevent cerebral haemorrhage. Aim for a diastolic of 90–95 mmHg to ensure adequate placental perfusion. Monitor maternal blood pressure (5–10 minutes intervals) and fetal heart rate (cardiotocography).

Acute treatment

Maintenance

| Start | 40 μg/min | (2.4ml/h) |

| 30min | 80 μg/min | (4.8ml/h) |

| 60min | 120 μg/min | (7.2ml/h) |

| 90min | 160 μg/min | (9.6ml/h) |

Do not increase if pulse is >140 or if target BP is reached. Reduction by 10–20 μg/min every 30 minutes.

Prolonged use (more than 24 hours) of hydralazine results in tachycardia and loss of antihypertensive effect. If required consider adding a β-blocker.

Intravenous therapy

Set a target BP. Increase infusion as stated until target BP is reached

| At 30min | 40mg/h |

| At 60min | 80mg/h |

| At 90min | 160mg/h |

To reduce, decrease by 10 mg/h every 30 min as required. Convert to oral therapy by giving 200 mg orally 1 hour prior to stopping infusion, followed by 200 mg three times daily.

Suspected fetal death

Any mother presenting with diminished fetal movements must be examined at once.

Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the obstetric woman

Myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction associated with labour or need for delivery is not a common situation (6.2 per 100 000 maternities). In pregnancy the majority of infarcts are transmural involving the anterior rather than posterior myocardium. The cause is usually coronary artery thrombosis where pre-existing arteriosclerosis or aneurysm of the artery may exist. Coronary artery spasm is also a possibility. Haemodynamic changes during labour and delivery more often precipitate myocardial infarcts in the primigravida in the postpartum period whereas infarct in multigravid mothers is usually an antepartum event. Maternal mortality (7.3%) and fetal mortality is high.

Management

Altman D, Carolli G, Duley L, et al. Do women with pre-eclampsia, and their babies benefit from magnesium sulphate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;. 2002;359:1877-1890.

Andra H, James MD, Margaret G, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy. A United States population based study. Circulation. 2006;113:1564-1571.

Baldwin KJ, Johanson RB, Anthony J. The acute management of severe hypertensive illness in pregnancy. O’Brien S, editor. The Yearbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 5. London: RCOG Press. 1997:233-245.

Besinger RE, Moniak CN, Paskiewicz LS, et al. The effect of tocolytic use in the management of symptomatic placenta praevia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;172:1770-1778.

Caspi E, Lotan Y, Schreyer P. Prolapse of the cord: reduction of perinatal mortality by bladder instillation and caesarean section. Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. 1983;19:541-545.

Chetty RM, Moodley J. Umbilical cord prolapse. South African Medical Journal. 1980;57:128-129.

Cortis BS, Gensini GG. Can the risks of myocardial infarction in pregnancy be reduced?. Cardiovascular Diseases. 1977;4:49.

Driscoll JA, Sadan O, Van Gelderen CJ, et al. Cord prolapse: can we save more babies? Case reports. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1987;94:594-595.

Duley L, Henderson-Smart D. Drugs for treatment of very high blood pressure during pregnancy. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2. Oxford: Update software; 2001.

Hankin GDU, Wendel GDJr, Leveno KJ, et al. Myocardial infarction during pregnancy: A review. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1985;65:139-146.

Ladner HE, Danielsen B, Gilbert WM. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy and the puerperium: a population based study. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;105:480-484.

Leerentveld RA, Gilberts EC, Arnold MJ, et al. Accuracy and safety of transvaginal sonographic placental localisation. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;76:759-762. 1990

Johanson RJ, Cox C, Grady K, et al. Managing Obstetric Emergencies and Trauma: The MOET Course Manual. London: RCOG Press, 2003.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Placenta praevia: Diagnosis and management. In: Guideline No 27. London: RCOG; 2001.

Towers CV, Pircon RA, Heppard M. Is tocolysis safe in the management of third trimester bleeding?. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;180:1572-1578.

Tucker D, Liu DTY, Ramoutar P. Myocardial infarction at term: a case report to consider management options. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;6:522-524.

Vago T. Prolapse of the umbilical cord. A method of management. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1970;107:967-969.