Chapter 11 Episiotomy and tears

Episiotomy is the term used for an incision in the perineum. Not all women require an episiotomy for delivery but considerable experience is necessary to determine when it is not needed. This incision is made:

TYPES OF INCISION

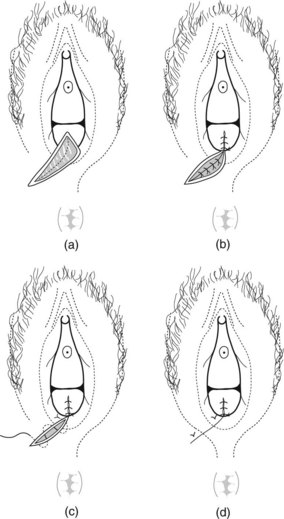

Medial incision

Medial incisions are made in the anatomical plane and are comfortable. There is less bleeding, and they are easy to repair. However, access is limited and the incision carries the risk of extension into the rectum, hence it is only used by someone experienced (Figure 11.1a).

Mediolateral Incision

This incision is safe, easy to perform, and thus the most commonly used. It is associated with least risk of anal sphincter damage. The cut must begin at the mid-point of the fourchette and is directed towards the ischial tuberosity into the ischiorectal pad of fat (Figure 11.1b).

J-shaped incision

This type of incision has the advantage of the medial incision and provides better access than the mediolateral approach. The lateral incision is made tangential to the brown of the anus (Figure 11.1c). It is excellent for the experienced surgeon.

TECHNIQUE

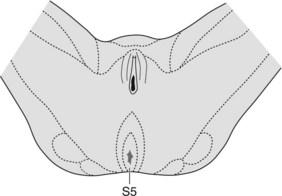

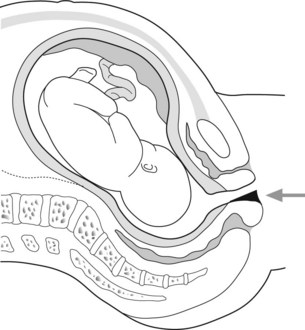

Figure 11.2 Using the fingers the fourchette is drawn away from the presenting part of the fetus before infiltration.

TIMING

DO

DO NOT

REPAIR OF AN EPISIOTOMY

RESUTURING EPISIOTOMIES

Breakdown of an episiotomy often follows infection of a haematoma. The following procedure should be adopted:

TEARS IN THE PERINEUM

Eighty-five per cent of vaginal deliveries are associated with some perineal trauma. These are graded as:

Superficial grazes and tears, if they are not bleeding, can be left. Second degree tears are repaired as for episiotomies. Skin edges, because they are ragged, may need interrupted rather than subcutaneous sutures.

Third and fourth degree tears are associated with 4% of vaginal deliveries with mediolateral episiotomy. Severe tears are more common in the nullipara (4%) birthweight over 4 kg (2%), occipitoposterior position (3%), long second stage (4%) and forceps delivery (7%).

Repair of a third degree tear requires:

CONSEQUENCES OF PERINEAL TRAUMA FOR WOMEN

Review women with severe tears 6 months or a year after delivery. Box 11.1 gives further information on third degree tears.

Box 11.1 Third degree tears: faecal incontinence

Bek KM, Laurberg S. Risk of anal incontinence from subsequent vaginal delivery after a complete obstetric and sphincter tear. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;99:724-726.

Browning GG, Motson RW. Results of Parks operation for faecal incontinence after anal sphincter injury. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition). 1983;286:1873-1875.

De Leeuw JW, Struijk PC, Vierhout ME, et al. Risk factors for third degree perineal ruptures during delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2001;108:383-387.

Glazener CMA, Abdalla M, Stroud P, et al. Postnatal maternal morbidity: extent, causes, prevention and treatment. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;102:286-287.

Mackrodt C, Gordon B, Fern E, et al. The Ipswich Childbirth Study: 2 A randomised comparison of suture materials and suturing techniques for repair of perineal trauma. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1988;105:441-445.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Guideline No. 23. Methods and Materials used in Perineal Repair. London: RCOG, 2004.

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, et al. Anal sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1905-1911.

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, et al. Third degree obstetric anal sphincter tears and risk factors and oucome of primary repair. BMJ. 1994;308:887-891.

Venkatesh KS, Ramanujam PS, Larson DM, et al. Anorectal complications of vaginal delivery. Diseases of colon rectum. 1989;32:1039-1416.

Wood J, Amos L, Rieger N. Third degree anal sphincter tears: risk factors and outcomes. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;38:414-417.