Chapter 15 Induction and augmentation of labour

Induction of labour is a process for initiation of uterine activity to achieve vaginal delivery. Induction rates between 10% and 25% reflects current policies, referral patterns and sometimes women’s choice. Labour is initiated to benefit principally the mother, the fetus or both and as an elective prophylactic procedure. In the UK, women with uncomplicated pregnancies are offered induction of labour after 41 weeks.

INDUCTION OF LABOUR AS THERAPY

This is considered for the following reason:

Close surveillance in labour is mandatory when induction is carried out to address fetal or maternal compromise. If fetal distress develops or labour is not progressing well early resort to caesarean section is advised.

INDICATIONS FOR INDUCTION

Maternal

Medical or obstetric conditions not responding to treatment and which threaten the woman’s health, such as heart failure, severe pre-eclamptic toxaemia and deteriorating renal function or central nervous system disorders.

Fetal

Presence of progressive growth restriction, abnormality not compatible with life, or fetal death.

Fetus and mother

Where induction of labour benefits both the mother and fetus, such as in poorly controlled diabetes, following rupture of fetal membranes or when chorio-amnionitis is evident. This indication is particularly pertinent in contemporary obstetric practice when women with medical conditions previously not considered suitable for pregnancy are now prepared to accept inherent risks to become mothers.

INDUCTION OF LABOUR AS PROPHYLAXIS

Induction of labour is also considered to anticipate potential complications. Examples are:

INDUCTION: GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO INDUCTION

Induction of labour should not be considered in the following situations:

REQUIREMENTS BEFORE INDUCTION OF LABOUR

Review medical and obstetric history. Perform clinical examination to exclude contraindications for induction of labour. Ensure the woman and her partner are fully informed of the risk and benefits and consent to the intended programme. Provide written information.

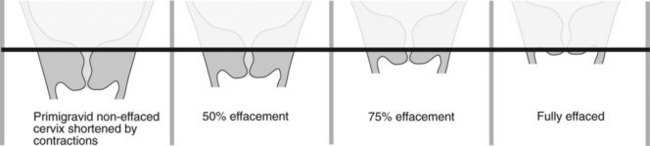

Perform vaginal examination to assess adequacy of pelvis and determine cervical status. Cervical dilatation, cervical length, consistency, position and station of presenting part are combined into a score – Bishop’s score (Table 15.1), often modified to describe cervical status (Figure 15.1). A low score forewarns increased likelihood of induction failure and need for cervical preparation or ripening.

Cervical dilatation exerts twice the influence on successful induction compared with cervical consistency.

INDUCTION OF LABOUR: PROCESS

Cervical status governs choice for methods to induce labour. A low or unfavourable cervical score necessitates a ripening process for effacement and/or softening of the cervix to facilitate cervical dilatation. This is achieved by drugs, for example prostaglandins, which soften the cervix and produce uterine activity to draw up or create cervical effacement. Membrane sweeping releases prostaglandins and provides a biomechanical advantage to initiate or assist induction.

Cervical ripening

Pharmacological substances such as prostaglandins are prescribed to prepare or ripen the cervix. The current most clinically acceptable and effective is prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 given intravaginally as a pessary, as water soluble gel or more recently in the form of a slow-released hydrogel is associated with least systemic side effects. Vaginal pH, moisture, temperature, and infection can, however, all affect efficacy of the preparation. Do not use obstetric cream for vaginal examination if prostaglandins may be given. Where appropriate membrane sweep is returning as an acceptable procedure for uncomplicated pregnancies over 40 weeks. Both vaginal gel and vaginal tablets are equally effective and use is governed by cost.

Induction of labour

Auscultate fetal heart and perform CTG trace for 30 minutes prior to the induction process. Omit if induction is for fetal demise. If the trace is non-reassuring, discuss delivering by caesarean section.

Bishop’s score of 4 or less

Administer 2 mg prostaglandin gel into posterior fornix. Give another 1 mg in 6 hours if needed. Review by experienced obstetrician 6 hours after second dose. Uterine activity usually starts 1 hour after administration of prostaglandin gel. Pharmacological effect lasts up to 4 hours. Continuous CTG monitoring is essential. When there is no urgency let the woman rest overnight and recommence the programme in the morning. The maximum total dose of PGE2used is 4 mg for primigravidae and 3 mg for multigravidae. Vaginal prostaglandin tablets are alternatives (3 mg PGE2 vaginally and repeat once in 6 hours). With ruptured membranes consider vaginal prostaglandin or intravenous oxytocin.

Bishop’s score between 4 and 7 (favourable cervix)

In primigravidae start with 1 mg prostaglandin gel. Repeat after 6 hours if indicated. Again if labour is not established review by experienced obstetrician 6 hours after second dose. A maximum of 4 mg PGE2 is advised.

In multigravidae start with 1 mg prostaglandin gel and repeat in 6 hours if required. Review 6 hours after last dose if labour is not established. A maximum of 3 mg is advised.

Uterine hypertonus or hyperstimulation may occur. Close fetal surveillance is essential. Monitor fetal heart rate for at least 60 minutes after inserting prostaglandins. Watch out for signs of uterine rupture when there is a lower segment caesarean section scar. If labour is not established by evening, return the woman to the ward if appropriate and repeat the programme in the morning. If labour ensues recommence fetal heart rate monitoring. Repeat tracing when mother is warded. If artificial rupture of membranes (ARM) is not possible after a course of prostaglandins review the situation with a senior obstetrician.

Induction of labour: artificial rupture of membranes

With a Bishop’s score of 8 or more the cervix is often sufficiently dilated to allow access to the fetal membranes. Options are:

Surgical induction of labour can be achieved by passage of an instrument through the cervical os to artificially rupture the fetal membrane. Drainage of amniotic fluid reduces the size of the uterine cavity and promotes more effective contractions by improving the myometrial length tension ratio. Prostaglandins are also released from the decidua. Onset of labour usually follows amniotomy in 6–12 hours. This interval before onset of labour is shortened by simultaneous use of intravenous infusion of an oxytocic such as Syntocinon.

Technique for low ARM (forewater rupture)

Make sure the woman and her partner give consent (verbal or written) and understand the reasons and steps for the procedure.

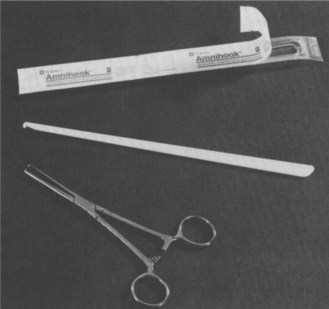

Place mother in the lithotomy position. Use sterile drapes and an aseptic technique. The fetal membranes in front of the presenting part can be ruptured using forceps such as Kocher’s forceps or various designs of amniohooks (Figure 15.2).

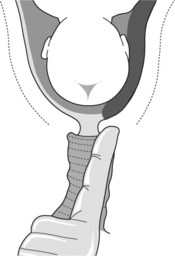

If placenta praevia has not been excluded by ultrasound examination palpate the vaginal fornices carefully. Suspect placenta praevia if a thick spongy sensation is felt between the fornices and presenting part of the fetus (Figure 15.3). Insert a finger through the cervical os. Palpate the membranes through the internal os for a distance of 2 cm to exclude pulsating vessels associated with vasa praevia or cord presentation.

When amniotomy is not contraindicated insert a second finger (index and middle fingers are used). Guide the forceps between the fingers to the membranes (Figure 15.4). The membranes are picked up by the forceps and ruptured by wiping the index finger over the tip of the forceps. This technique allows good control of the amount of tear and the rate of escape of amniotic fluid. Record quantity and colour of liquor (blood stained, meconium or clear).

Alternatively introduce an amniohook through the cervix. This is guided to a safe area of the presenting part of the fetus (for example, away from the fetal face). Approximate amniohook to the membrane by the index finger. The hook is withdrawn to tear the membranes. An advantage of this option is the need for less cervical dilatation, but the size of the tear is less predictable.

Infusion of synthetic oxytocin (Syntocinon)

Points to note with Syntocinon usage are:

Doses in bold italics are quantities above those referred to in the summary of product characteristics of 20 mU/min (Table 15.2).

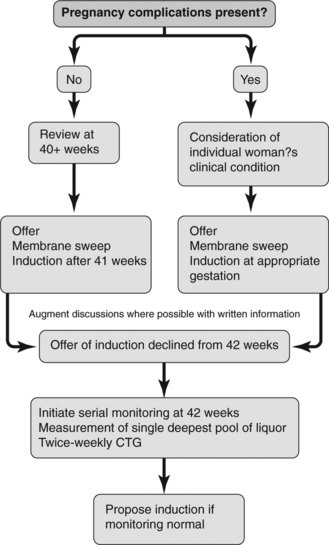

Figure 15.6 presents an algorithm for induction of labour depending on the presence or absence of complications in pregnancy.

RISKS OF INDUCTION

This describes the situation when effective uterine activity is not established or maintained. Failure is less likely for gestations near term or when the Bishop’s score is high. When membranes are ruptured there is the risk of infection. Deliver by caesarean section if there is fetal or maternal compromise.

Once membranes rupture intrauterine and fetal infection is more likely. Some women such as those with diabetes are more susceptible. Where possible exclude active vaginal infection such as cervical herpes and presence of Group B streptococcus. Once membranes rupture monitor maternal pulse and fetal heart rate and maternal temperature. Aim to achieve delivery within 24 hours.

Incidence of cord prolapse is 0.1–0.5% following membrane rupture. Exclude cord presentation before rupturing membranes. This complication is more likely when the fetal presenting part is not well applied to the cervix or when there is polyhydramnios.

Pharmacological agents used to stimulate uterine activity can lead to excessive amplitude and frequency of contractions. Once the contraction frequency exceeds 5 per 10 minutes uterine activity becomes less efficient. Hyperstimulation follows use of high concentrations of oxytocics or where a woman is particularly sensitive to the drug. Hyperstimulation causes fetal hypoxia and threat of uterine rupture particularly in the grand multipara or in women with previous caesarean section scars. β-sympathomimetics such as ritodrine (50 μg to maximum of 350 μg per minute) or terbutaline, 250 μg subcutaneously or in 5 ml saline can be given intravenously to overcome hyperstimulation (20 μg/min should not be exceeded).

INDUCTION OF LABOUR: SPECIAL SITUATIONS

Previous caesarean section

Pre-labour rupture of membranes

For term fetus (36 completed weeks)

Induce labour immediately if there is threat or evidence of maternal or fetal infection. Deliver by caesarean section if CTG suggests evidence of fetal compromise.

If there is no risk of complication or fetal or maternal compromise discuss options with the woman. Conservative management for 24 hours to await spontaneous onset of labour is acceptable. Induce labour after 24 hours of ruptured membranes.

For 34 weeks’ gestation to term

Allow pregnancy to continue. When obstetric risk is present such as infection or fetal compromise induce labour or deliver by caesarean section where appropriate.

If conservative management is acceptable take cervical swabs. Transfer to antenatal ward and commence 4 hourly recording of maternal pulse rate and temperature. Check abdomen for tenderness at the same time. Perform twice daily fetal CTG recordings and weekly ultrasound scan of the fetus. Deliver at 37 weeks or if fetal compromise becomes evident.

Before 34 weeks’ of gestation

In the absence of contraindications such as infection give two doses of 12 mg dexamethasone at 12 hourly intervals. Dexamethasone can cause a transient rise in white cell count for 24–36 hours. The fetal heart rate change is difficult to interpret but fetal tachycardia is a useful guide for infection. Give appropriate antibiotics for pathogens. Deliver if chorioamnionitis is evident. Consider caesarean section if there is fetal risk.

Adopt the same criteria for induction as described above. Vaginal prostaglandin is not contraindicated.

Breech presentation

Contemporary practice advises attempts at external cephalic version when there is no contraindication and if this is unsuccessful deliver by caesarean section. The woman’s informed opinion must be considered. Current evidence recommends that caesarean section for breech presentation is the safest approach.

Twin pregnancies

In the absence of obstetric complications induction of labour by amniotomy or use of prostaglandin is not contraindicated. Requirements for twin delivery must be satisfied. The first twin should be in cephalic presentation. Breech presentation of the first twin suggests the need for delivery by caesarean section.

Intrauterine fetal death

The main risks associated with intrauterine fetal death are infection, and if the dead fetus is retained more than four weeks coagulopathy may develop.

KEY POINTS IN INDUCTION OF LABOUR

AUGMENTATION OF LABOUR

This process describes enhancement of uterine contractions when progress of labour is slow. Before augmentation exclude malpresentation, gross disproportion and fetal or maternal compromise.

Decision to augment labour must follow assessment of situation by experienced obstetrician. This decision must be acceptable to the woman. Aim to achieve adequate contractions (frequency of four to five contractions per 10 minutes, each contraction lasting 40–60 seconds). Contractions should produce cervical dilatation and descent of the presenting part. A wide range of uterine activity can produce cervical dilatation averaging 1 cm/h.

Augmentation, like induction of labour, must be conducted with due care. This care includes nursing support, pain relief and close surveillance.

Augmentation before 3 cm cervical dilatation

In the latent phase of labour, augmentation is advised after 8 hours of painful contractions occurring at a frequency of 2 every 10 minutes if there is slow progress (World Health Organization (WHO) 1994). Exclude contraindications to labour.

Augmentation after 3 cm cervical dilatation

This is considered when cervical dilatation drifts 2–3 hours to the right of the alert line of the normal partogram (WHO 1994). Exclude contraindications to further labour. Rupture fetal membranes if these are still intact. The same Syntocinon regimen for induction of labour is used. Labour progress is measured both in terms of cervical dilatation and descent of the fetal head. Cervical dilatation without descent of the fetal head forewarns of possible disproportion.

Close surveillance is mandatory. If fetal distress develops or little change is detected after 4 hours of adequate contractions consider delivery by caesarean section. In the absence of contraindications 6–8 hours of oxytocin can result in optimal outcome.

Obstructed labour in primigravidae leads to incoordinate labour or cessation of uterine activity. In multigravidae the uterus attempts to overcome the obstruction by increasing frequency and intensity of contractions with resultant tetanic uterine activity and risk of uterine rupture.

Arulkumaran S, Koh CH, Ingemarsson I, et al. Augmentation of labour. Mode of delivery related to cervimetric progress. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;27:304-308.

Bakketeig LS, Bergsjo P. Post-term pregnancy: magnitude of problem. In: Chalmers M, Enkin, Keirse M. Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Bishop EH. Pelvic scoring for elective induction. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1964;24:266-268.

Bouvain M, Iron O. Sweeping the membranes for inducing labour or preventing post-term pregnancy (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software; 2001.

Calder AA. Management of unripe cervix. In: Keirse MNJC, Anderson ABM, editors. Human Parturition. Leiden: Leiden University Press; 1979:201-217.

Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy 1995 4th Annual Report Concentrating on Intrapartum related Deaths. Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium, London

Crowley P. Elective induction of labour at 41 weeks’ gestation (revised 5 May 1994). Pregnancy and children module. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJBC, Renfrew MJ, et al. The Cochrane Database (database on disk and CD ROM). Oxford: Update Software, 1995. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2.

Frait G, Daniel Y, Lessing JB, et al. Can labour with breech presentation be induced?. Gynecological and Obstetric Investigations. 1998;46:181-186.

Friedman EA. The graphic analysis of labour. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1954;68:1569.

Griffiths M 2003 A survey of current practice and opinion regarding methods for the induction of labour. Clinical report, Pharmacia, Milton Keynes, UK

Johnson TA, Greer IA, Kelly RW, et al. The effect of pH on release of PGE2 from vaginal and endocervical preparations for induction of labour: an in vitro study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;99:877-880.

Liu DTY, Kerr-Wilson R. Cervical dilatation in spontaneous and induced labours. British Journal of Clinical Practice. 1977;31:177.

MacKenzie IZ. Prostaglandin induction and the scarred uterus. Second European Congress on Prostaglandins in Reproduction, The Hague 1991. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, 1991;29-39.

MacKenzie IZ, Magill P, Burns E. Randomised trial of one versus two doses of prostaglandins for induction of labour. I Clinical outcome, II Analysis of cost. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:1062-1067.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Research Planning Workshop. Electronic fetal heart rate monitoring: research guidelines for interpretation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;177:1385-1390.

Nuutila M, Kajanoja P. Local administration of prostaglandin E2 for cervical ripening and labour induction: the appropriate route and dose. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1996;75:135-138.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Guidelines on induction of labour. London: RCOG Press, 1998.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Induction of labour. Evidence-based clinical guideline number 9. London: RCOG Press, 2001.

Tarnow-Mordi W, Shaw JCL, Liu DTY, et al. Iatrogenic hyponatraemia of the newborn due to maternal fluid overload: a prospective study. BMJ. 1981;283:639.

Wing DA, Rahall A, Jones MM, et al. Misoprostol: An effective agent for cervical ripening and labour induction. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;172:1811-1816.