Chapter 19 Malpresentation and malpositions

DEFINITIONS

Malposition

This describes a vertex presentation which is not in the fully flexed anterior position, for example a deflexed head, and occipitolateral and occipitoposterior positions. The occiput is the denominator. A higher incidence is seen in mothers of African and Chinese origin.

Malpresentation

This describes all presentations which are not vertex, for example: face, brow, shoulder and breech presentation.

Labour

During pregnancy attention is drawn to these complications when the fundal height does not correspond to gestational dates, the lie is not longitudinal or the fetal head is not engaged. The fetal head may appear large because it is abnormal, or is in malposition. Before, or following labour, some of these complications may resolve spontaneously.

An experienced obstetrician should be called to confirm the diagnosis and then to decide about labour and supervise the mode of delivery.

Diagnosis of malpositions signals need to anticipate operative delivery.

DEFLEXED HEAD

This describes a vertex presentation where the fetal head is not fully flexed to present the most advantageous biparietal diameter of 9.5 cm. This situation arises when:

Labour is prolonged or may be arrested. Deflexion can progress to a brow or face presentation.

OCCIPITOPOSTERIOR POSITIONS

These describe the situation where the occiput is in the posterior part of the pelvis. This position is found in 10–13% of all vertex presentations. Contributory factors include:

Types

Diagnosis

Palpation

The fetal limbs are anterior and give a hollowed appearance to the woman’s lower abdomen. The head is not engaged and the sinciput is felt superficial to the occiput on palpation when the woman is lying horizontally. The fetal shoulder and loudest heart sounds are located well lateral to the midline.

Vaginal examination

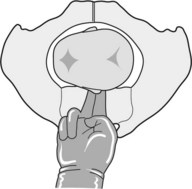

The presenting part is poorly applied to the cervix. Deflexion is common. The anterior fontanelle is easily felt beneath the symphysis. If diagnosis presents difficulty, pass a finger alongside the fetal face and locate the ear. Running the fingers across the root of the ear will show that the pinna points in the direction of the occiput (Figure 19.3).

Course of labour

This depends on the quality of uterine activity, whether disproportion is present and the type of pelvis.

Uterine activity

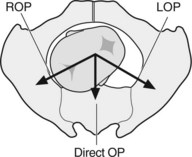

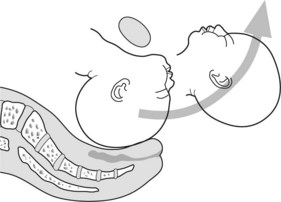

Strong regular contractions encourage flexion, engagement and rotation to an occipitoanterior position. Labour tends to be longer because the application of the presenting part of the fetus to the cervix is poor. In about two-thirds of such women, rotation through an arc of 135° from an occipitoposterior to an occipitoanterior position will be achieved (Figure 19.4). Extra time in labour is required to achieve this.

Gynaecoid and other adequate pelvis

Descent and flexion of the head occurs. Long rotation to the occipitoanterior position takes place at the level of the pelvic floor. Subsequently delivery is normal.

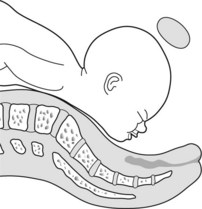

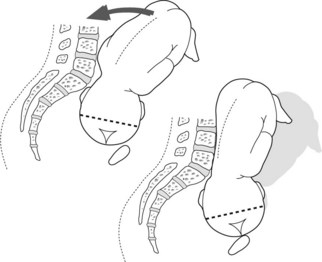

Anthropoid (ellipsoid) pelvis

Rotation to the occipitoanterior position is not favoured because the transverse diameter of the pelvis is narrow. The vertex rotates posteriorly a short distance, through 45° to deliver in the persistent occipitoposterior position. Deflexion is common, hence the presenting diameter is the wider occipitofrontal (11.5 cm) position. The head delivers by flexion followed by extension to allow the brow and the face to appear beneath the symphysis. The wider presenting diameter of the fetal head causes more trauma to the vagina, hence an episiotomy is necessary to prevent tearing. Assistance with forceps or ventouse extraction to complete the delivery is commonly required.

Android pelvis

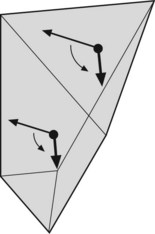

Rotation to an anterior position becomes progressively more difficult with descent because the pelvis is narrow anteriorly, and the walls of the lower part of the android pelvis converge towards the outlet. Spontaneous rotation to an anterior position is possible if the pelvis diameters are adequate. In a marginal-sized pelvis, failure to rotate can occur at any level of the pelvis. The vertex can remain in the occipitoposterior position or rotation may be arrested with the head in the transverse position. When failure to rotate or descend occurs high in the pelvis, this situation is termed deep transverse arrest (DTA) (Figure 19.5). Delivery will require assistance.

Management

FACE PRESENTATION

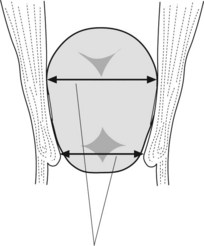

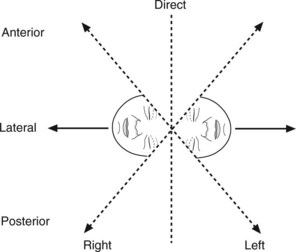

The incidence of face presentation is 1 in 500 deliveries. The diameter for consideration is the submentobregmatic, which is 9.5 cm. The denominator is the chin or mentum which may be found in any one of eight positions (Figure 19.6). During labour the chin is the lowest point or leading part. Seventy-five per cent of face presentations are in the mentolateral or mentoanterior positions. Rotation in the lower half of the pelvis to the direct mentoanterior position usually occurs if the pelvis is adequate. The head is delivered by flexion. Assisted delivery is necessary for mentoposterior positions. Forceps rotation may be tried, but caesarean section is usually required for delivery (Figure 19.7).

Figure 19.6 Mentum (chin) in the right and left posterior, lateral and mentoanterior positions together with direct mentoposterior and mentoanterior.

Diagnosis

Primary face

This is diagnosed when there is a non-engaged head, the head feels large or when the extended head is felt on the same side of the uterus as the fetal back. Radiology or ultrasound scanning is carried out to confirm suspicion. Assess adequacy of pelvis and exclude any abnormalities (fetal and maternal).

Secondary face

Suspect this diagnosis if the presenting part of the fetus appears low yet a large part of the head is palpable suprapubically. The eyes, nose, supraorbital and alveolar ridges, and the mouth can be felt on vaginal examination. Unlike the anus, the mouth does not grip the examining finger and firm fetal gums are felt. Ultrasound scan can confirm the diagnosis (Figure 19.8).

Management

Mentoanterior position

Labour is prolonged. The presenting part is poorly applied. The engaging diameter 9.5 cm (submentobregmatic) is at a lower level than the biparietal (9.5 cm) diameter. The diameter of 9.5 cm is thus presented twice at 90° to the cervix (Figure 19.9). In ideal conditions spontaneous delivery can occur. Usually an episiotomy and assistance with forceps is required for vaginal delivery. The ventouse extractor is contraindicated. Failure to progress in the first stage of labour necessitates a caesarean section.

Mentolateral position

In an adequate pelvis, expect rotation to the mentoanterior position and an assisted vaginal delivery. Rotation occurs at or below the level of the ischial spines. Manual or forceps rotation may be required. If the pelvic outlet is suspect or spontaneous rotation is arrested in mid-pelvis, deliver by caesarean section.

Mentoposterior position

Unless the fetus is very small or the pelvis capacious, the shoulder and vertex cannot be accommodated at the same time. Obstruction is inevitable. Attempting rotation to the mentoanterior position is seldom advised. Deliver by caesarean section. If the fetus is dead consider delivery by craniotomy and forceps (only if the operator is experienced). Facial oedema and bruising is usual.

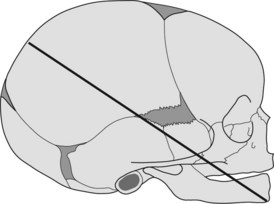

BROW PRESENTATION

Brow presentation has an incidence of approximately 1 in 2000 or more deliveries.

Types

Diameters for consideration

The fetus presents by the mentovertical diameter (13.5 cm) which is greater than the largest pelvic diameter of 12.5 cm (Figure 19.10).

Diagnosis

COMPOUND PRESENTATION

This describes a situation when the hand or forearm accompanies the presenting part of the fetus. It is usually associated with poor application of the presenting part and a small or preterm infant in a large pelvis.

PARIETAL PRESENTATION

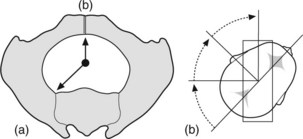

In a flat pelvis the vertex engaging in the occipitolateral position will have to tilt (attitude of asynclitism) sideways to swivel past the sacral promontory and the symphysis.

Anterior asynclitism

This is when the parietal eminence in front tilts behind the symphysis. This is a favourable presentation and once the biparietal eminences swivel past the sacral promontory and symphysis, rotation to occipitoanterior or posterior is the usual course (Figure 19.11).

Posterior asynclitism

This is when the parietal eminence at the back enters the pelvis first by slipping past the sacral promontory. This is less likely to succeed because unlike anterior asynclitism in which the fetal body can lean anteriorly to assist engagement of the anterior parietal eminence, in posterior asynclitism the mother’s spinal column prevents this action of the fetal body. Failure of either anterior or posterior asynclitism to engage the fetal head means that caesarean section is necessary for delivery (Figure 19.12).

SHOULDER PRESENTATION (TRANSVERSE OR OBLIQUE LIE)

In both transverse and oblique lie, the shoulder is the most common presenting part. In an oblique breech the ilium may present. The causes of shoulder presentation are listed in Table 19.1.

Table 19.1 Causes of shoulder presentation

| Maternal | Fetal |

|---|---|

| Relaxed multigravid uterus (most common cause) | |

| Pelvic contracture | Prematurity |

| Uterine abnormality | Fetal death |

| Obstruction by intra or extrauterine masses |

Diagnosis

Abdomen

The fundal height appears small for dates (unless there is multiple gestation or polyhydramnios). The uterus appears broad with fullness in the flanks. No presenting part is palpable in the pelvis. The head or breech is felt opposite the iliac crest or at right angles to the mid-line.

Vaginal

No vaginal examination should be performed until placenta praevia is excluded. Avoid membrane rupture and risk of cord or arm prolapse. If the membranes have ruptured, examine immediately to exclude cord prolapse. The pelvis feels empty with the ilium and/or shoulder presenting. The fetal ribs give a characteristic ‘washboard’ feel.

Prognosis

This is a dangerous situation for both the fetus and the mother. Spontaneous delivery is not possible unless the fetus is very small. The risk of cord prolapse, shoulder impaction, uterine rupture and the need for classical caesarean section all increase maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity.

Management

Gardber GM, Tuppurainen M. Persistent occiput posterior presentation – a clinical problems. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1994;73:45-47.

Gardber GM, Laakkonen E, Salevarra M. Sonography and persistent occiput posterior position:a study of 408 deliveries. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;91:746-749.

Holmberg NG, Lilieqvist B, Magnusson S. The influence of the bony pelvis in persistent occiput posterior position. Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica Supplement. 1977;66:49-54.

To WW, Li IC. Occipital posterior and occipital transverse positions: reappraisal of obstetric risks. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;40:275-279.