Managing Chemicals Safely

OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

WRITTEN HAZARD COMMUNICATION PROGRAM

INVENTORY AND LISTING OF HAZARDOUS CHEMICALS

LABELS AND OTHER FORMS OF WARNING

EMPLOYEE INFORMATION AND TRAINING

HOW THE OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION SOLVES A

OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE TO HAZARDOUS CHEMICALS IN LABORATORIES

GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR WORKING WITH LABORATORY CHEMICALS

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

Develop a method to determine the hazard potential of chemicals.

Develop a method to determine the hazard potential of chemicals.

Design and maintain a written hazard communication program.

Design and maintain a written hazard communication program.

Identify the four ways “OSHA solves a problem.”

Identify the four ways “OSHA solves a problem.”

Design and maintain a written chemical hygiene plan.

Design and maintain a written chemical hygiene plan.

HAZARD COMMUNICATION PROGRAM

The U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has estimated that more than 32 million workers are exposed to 650,000 hazardous chemical products in more than 3 million American workplaces. This exposure poses a serious problem for workers and their employers.

The basic goal of a hazard communication program is to be sure employers and employees know about work hazards and how to protect themselves; this knowledge should help reduce the incidence of chemical source illness and injuries.

If one were to ask most dental practitioners about their personal risk of experiencing an occupationally related injury, their responses most likely would include incidents such as needlestick accidents, allergies, burns, abrasions, or muscle strains. Being injured on the job while using or handling a hazardous material, such as a skin exposure to an acid solution, often would not be mentioned. Most health care workers consider topics such as safer use of chemicals in the workplace to be problems primarily associated with large manufacturing facilities, such as oil refineries, chemical manufacturers, steel mills, coal mines, and metal fabrication shops. Unfortunately, significant numbers of workers in dental environments are exposed to and injured each year by hazardous materials while performing normal clinical and laboratory duties.

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Millions of workers in the United States are occupationally at risk for exposure to one or more hazardous chemicals (Table 22-1). Almost 650,000 chemicals can be purchased in the United States, and literally thousands of new chemicals are introduced each year. The risk of exposure is increasing continually, and the workplace use of toxic chemicals has become commonplace.

TABLE 22-1

Important Definitions for a Hazard Communication Program

| Term | Definition |

| Chemical | Any element, chemical compound, or mixture of elements and compounds |

| Chemical distributors | A business, other than a chemical manufacturer or importer, that supplies hazardous chemicals to other distributors or to employer |

| Chemical manufacturers and importers | An employer with a workplace where chemical(s) are produced for use or distribution |

| Employee | A worker who may be exposed to hazardous chemicals under normal operating conditions or in foreseeable emergencies; some workers, such as office workers or bank tellers, encounter hazardous chemicals only in nonroutine, isolated instances and are not covered by the Hazard Communication Standard |

| Employer | A person engaged in a business where chemicals are used, distributed, or produced for use or distribution, including a contractor or subcontractor |

| Engineering controls | Procedures and materials that help prevent employee exposure to hazardous chemicals. Examples include changing a chemical to a less problematic form or subcontracting a process to another location or facility |

| Exposure (“exposed”) | Subjection of an employee to a hazardous chemical in the course of employment through any route of entry (inhalation, ingestion, skin contact, absorption), including potential (e.g., accidental or possible) exposure |

| Hazardous chemicals | A chemical for which statistically significant evidence based on a scientifically designed and conducted study indicates the acute or chronic health effects that may occur to exposed employees; many chemicals used within dental offices/clinics are considered hazardous |

| Hazard warning | Words, pictures, symbols, or combinations thereof appearing on a label or other appropriate form of warning that convey the specific physical or health hazard(s), including target organ effects, of the chemical(s) present in a container |

| HazCom compliance officer | An employee responsible for clinic/office compliance with the HazCom Standard; the person is responsible for listing all hazardous chemicals, collection of matching MSDSs, preparation of labels and warning signs, and the transfer of necessary safety information and training employees |

| Written HazCom program (WHCP) | A compliance process for the Hazard Communication Standard that includes a written clinic/office program manual, container labeling, and other forms of information transfer and warnings and employee training; best if administered by a HazCom compliance officer |

| HazCom Standard | The Hazard Communication Standard (aka “Employee Right to Know”) that has the goal of preventing employee exposures to hazardous chemicals; information from manufacturers of hazardous chemicals must be conveyed by employers to employees; facilities are responsible to ensure that the information is received and understood; facilities enhance safety through their HazCom program |

| Health hazard warnings | Words, pictures, symbols, or combinations appearing on a label or other appropriate form of warning that conveys the specific physical or health hazard(s), including target organ effects, of the chemical(s) present in a container |

| Label | Any written, printed, or graphic material displayed on or affixed to containers of hazardous chemicals that provides necessary information |

| MSDS | Written or printed material (material safety data sheet) concerning a hazardous chemical; an MSDS for each hazardous chemical listed within a facility must be obtained |

| Performance standard | A combination of procedures and materials (work practices, engineering controls, personal protective equipment, and training) to comply with an OSHA standard; OSHA does not usually dictate what process is to be followed; rather, it describes the outcome of some behavior, for example, keeping exposures within some limit; how well this is done can be called proper performance or proper achievement (level of compliance) |

| Personal protective equipment and devices | Specialized clothing or equipment worn by an employee for protection against a hazard; general work clothes usually are not designed or intended to prevent exposure to hazardous chemicals |

| Physical hazard | A chemical for which scientifically valid evidence indicates that it is a combustible liquid, a compressed gas, explosive, flammable, an organic peroxide and oxidizer, pyrophoric, unstable (reactive), or water reactive |

| Work practice controls | Means that reduce the likelihood of exposure by altering the manner in which a task is performed; for example, the use of a fume hood or vacuum evacuation |

Adapted from Occupational Safety and Health Administration: 29 CFR Part 1910.1030, Hazard communication; final rule Fed Regist 59:6126, 1994; and US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Chemical hazard communication (OSHA 3084), Washington, DC, 1995, US Government Printing Office.

Adverse exposure to chemicals can have serious health consequences. Heart, kidney, liver, and lung tissues could be damaged. The result could be a variety of diseases that range from short-term discomfort (e.g., burns or rashes) to life threatening (e.g., cancer, sterility, or organ failure). Preventing exposure to hazardous chemicals is the ultimate goal. Also important is the proper response when an exposure does occur.

OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has for more than 30 years monitored and helped to improve safety conditions in the workplace. The greatest initial need (numbers of employees and severity of injuries), as one would expect, was (and remains) based in large and naturally dangerous work sites. Through a process of improving engineering controls and changing work practice controls (see Table 22-1), OSHA’s work has begun to reduce the number of workplace injuries.

In time, OSHA issued comprehensive standards that held the weight of law. Noncompliance even in the absence of injury could result in citation, fines, and even temporary closure for the employer. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration also began to describe the required performance standards (see Table 22-1) expected from various pieces of work equipment (e.g., ladders, pipes, and electric service). Then OSHA applied Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards for maximum workplace exposure to chemicals, such as gases and volatile chemicals, radioactivity, and even heat and sound.

Finally, OSHA generated standards for the development, use, and review of personal protective equipment (PPE) and devices (see Table 22-1). In dental offices examples of PPE include gloves, masks, respirators, glasses, and uniforms for employees.

The overall goal was to minimize the chances of occupationally related injuries through several mechanisms. Success of such efforts is based on a number of interrelated factors. Of course, issuance of reasonable and reliable standards by OSHA is the guiding force. However, employers must make themselves knowledgeable of what is required and create within their environments as safe a workplace as possible. Employees also must be aware of the required standards and be active participants in the process. Although employers must provide proper safe working environments, employees must comply with implementation and performance of the processes.

Over the past 15 years, dental workers have become aware of OSHA activities. For example, without the emergence of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in the United States and the involvement of OSHA in health care settings, this book probably would not have been written. Before 1986, an overall interest in infection control, hazardous materials handling, and waste management was modest. This lack of concern negatively affected employee safety. However, with the growing epidemic of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, the interests of health care professionals and the general population grew. A heightened awareness of an increased need for patient and practitioner safety quickly developed.

HAZARD COMMUNICATION STANDARD

The main directive of OSHA is the protection of employees. The response of OSHA to current needs involves development of new standards and broadening the scopes of others. Most dental workers are acutely aware of the OSHA Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens; Final Rule (issued December 6, 1991). In fact, the majority of interest, effort, and resources with dental environments involves infection control. Conversely, relatively little attention is paid to other OSHA standards. One particularly deficient area is the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard, CFR 29.1910.1200 (HazCom Standard, HazMat Program, “Employee Right to Know”; see Table 22-1).

On September 23, 1987, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, in an attempt to promote safer use of hazardous materials, began to require chemical manufacturers, chemical importers, and chemical distributors to provide material safety data sheets (MSDSs) (see Table 22-1) with their shipments of all hazardous chemicals.

Initially, the center of activity involved manufacturing locations. However, with continued evidence of employee injuries, OSHA on May 23, 1988, began to require that employers from the nonmanufacturing sector (including health care facilities) comply with all provisions of the HazCom Standard. Even though the standard has been in effect for almost 10 years, compliance by dental clinics/offices is less than universal. Such deficiencies could be related to heightened concern about (and overemphasis on) infection control issues or lack of interest or awareness of the HazCom Standard. In any case, dental clinics and offices must comply with all tenets of the standard. A significant proportion of OSHA inspections involves complaints associated with injuries or the potential for injury involving the handling, use, storage, and disposal of hazardous materials.

Purpose of the Hazard Communication Standard

The purpose of the HazCom Standard is to ensure that hazards of all chemicals produced or imported be evaluated and that employers transmit the information concerning such hazards directly to employees. Information is conveyed through a comprehensive hazard communication program (see Table 22-1). The program includes a written clinic/office program manual, container labeling, and other forms of warning, MSDSs, and employee training.

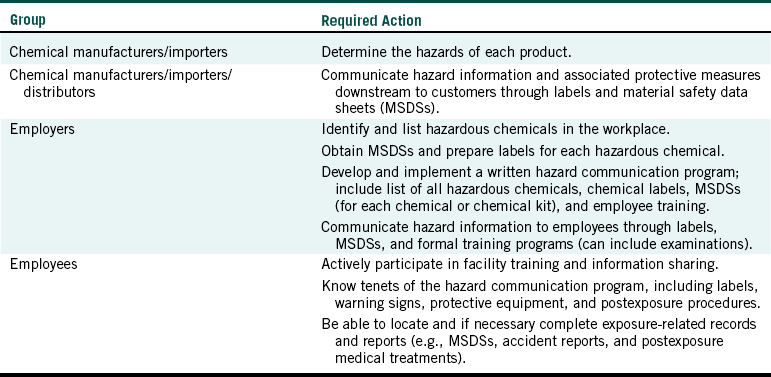

Users of hazardous materials are not in a position to easily evaluate the potential hazards associated with the chemicals. Logically, this responsibility falls to the chemical manufacturer or importer and eventually to the chemical distributors. The responsibility of employers is to inform and train their employees (see Table 22-1) concerning all safety materials provided, including all warnings, required personal protective devices, and safer handling and disposal methods.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has a variety of materials and publications to help employers and employees develop and implement effective hazard communication programs. One can obtain brochures on related topics by contacting the Department of Labor, OSHA/OSHA Publications, P.O. Box 37535, Washington, DC 20013-7535 (Box 22-1). One can obtain single copies at no charge by sending a self-addressed mailing label with the request. More extensive information kits are available for a fee from the U.S. Government Printing Office at Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, 732 N. Capitol St., NW, Washington, DC 20401, or by calling (202) 512-0000. Some items are available as downloads from the Internet.

Scope and Application of the Hazard Communication Standard

As previously stated, chemical manufacturers and importers are charged to assess the hazards associated with the use of their products. Distributors also must inform their clients of the hazards. In turn, employers must inform their employees. The HazCom Standard covers any workplace that employs workers (even one).

Hazardous chemicals involved in the standard are limited to those present in the workplace to which employees may be exposed under normal working conditions and in the case of a foreseeable emergency (e.g., an employee may not directly use a chemical but must be informed and trained about the proper procedures to follow if another employee were to drop and break open a jar of the chemical).

Technically, OSHA considers most health care facilities, including dental clinics or offices, to be “laboratories.” Employers must ensure that employees are informed and trained considering the types and amounts of hazardous materials present, the labeling system and warning signs used, the location and use of MSDSs, and procedures to be followed in case of emergencies.

Some chemicals are exempt from the standard. These chemicals include tobacco and tobacco products; wood and wood products; and food, drugs, cosmetics, or alcoholic beverages packaged and sold for consumer use. Foods, drugs, or cosmetics intended for personal consumption by employees while at work are also exempt. Consumer products (e.g., glass cleaner) used in a manner similar to those used by persons at home (applications, amounts used, and duration and frequency of use) generally are considered as not being hazardous. Finally, any chemical defined as a “drug” by the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act when present in its solid, final form, ready for direct administration to patients (e.g., aspirin) is exempt.

Before reviewing the details of the various parts of the HazCom Standard, a brief review of its design may be helpful. This standard is different from other OSHA standards in that it covers all hazardous chemicals (not just those associated with a certain type of workplace). The rule incorporates a “downstream flow of information.” Producers must inform distributors, who then tell employers, who must transmit information to their employees. Table 22-2 describes the process.

HAZARD DETERMINATION

The standard requires a list of hazardous chemicals in the workplace as part of the written hazard communication program (WHCP). The list eventually will serve as an inventory of everything for which an MSDS must be maintained.

The quality of a hazard communication program depends on the adequacy and accuracy of the hazard assessment. A hazardous chemical is any chemical that is a physical hazard or a health hazard (see Table 22-1). The EPA specifically designates which chemicals are hazardous. The EPA considers a chemical as hazardous if it can catch fire, if it can react or explode when mixed with other substances, if it is corrosive, or if it is toxic. Included are chemicals that are flammable, spontaneously ignitable, explosive, oxidizing agents, corrosive, toxic, or radioactive.

The EPA estimates that the average American house with a garage holds about 30 gallons of materials that can be considered hazardous. Consumers readily use many of these items, including gasoline, fertilizers, pesticides, strong acids or bases, lubricants, paint and varnishes, drain cleaners, and engine coolants. Many chemicals can be considered hazardous for more than one reason (e.g., gasoline is flammable, explosive, and toxic and at times can ignite spontaneously). Although the volume of hazardous materials in a dental clinic/office may not exceed that of many households, the number and forms of potentially harmful chemicals is usually far greater. Of course, the standard regulates safety in the workplace, not within residences.

The identification, evaluation, and notification of any chemical as being hazardous are the initial responsibility of its manufacturer or importer. These entities may generate their own scientific data, or when appropriate they may cite previously published information. Distributors are required to pass along this information to their clients. Hazardous means any chemical that has shown the capability of causing a physical or a health hazard. Toxicity and carcinogenicity are of significant importance. Although many chemicals have been tested, literally thousands of new compounds are produced each year. Many chemicals in common use have not been evaluated completely. Even if considered to be toxic or carcinogenic, debate on the status of a chemical can continue for an extended period. The stories associated with the investigation of dioxin, asbestos, chlorine, formaldehyde, and even the sweetener saccharin have proved legendary. When in doubt, one can consult federal chemical registries (e.g., The Registry of Toxic Effects of Chemical Substances produced by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health). Some hazardous materials are listed in the HazCom Standard itself.

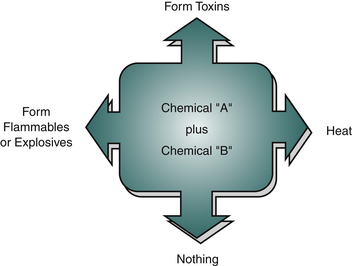

For a single, pure chemical such as ethanol to be used in dental environments is uncommon. A more frequent event is the mixing of chemicals. Kits containing various chemicals are mixed to achieve the desired end product. Trituration of amalgam is a common example of chemical mixing in a dental clinic/office. The manufacturer or importer (and eventually the employer) of a chemical kit must identify the hazards associated with mixing. The combination of chemicals initially may involve more than one hazardous chemical. The result of such combinations can vary (Figure 22-1). Chemicals that are benign when separate can produce an end product of significant danger after being mixed. Warning information as to the type of hazard generated and procedures to handle, use, and store the mixture safely must be provided. Warnings must include specific comments concerning the types of personal protective equipment that need to be worn and the procedures to be used for exposure or for disposal.

WRITTEN HAZARD COMMUNICATION PROGRAM

All workplaces where employees are exposed to hazardous chemicals must have a written plan that describes how the standard will be implemented in that facility.

The HazCom Standard commonly is referred to as the “Employee Right to Know Rule.” Another way to look at the standard is as the “No Surprises Rule.” The goal is that by training and the sharing of information, employee injuries involving hazardous chemicals can be kept to a minimum. Employers must develop, implement, and maintain at the workplace a written, comprehensive hazard communication program that includes provisions for container labeling, collection and availability of MSDSs, and an employee training program.

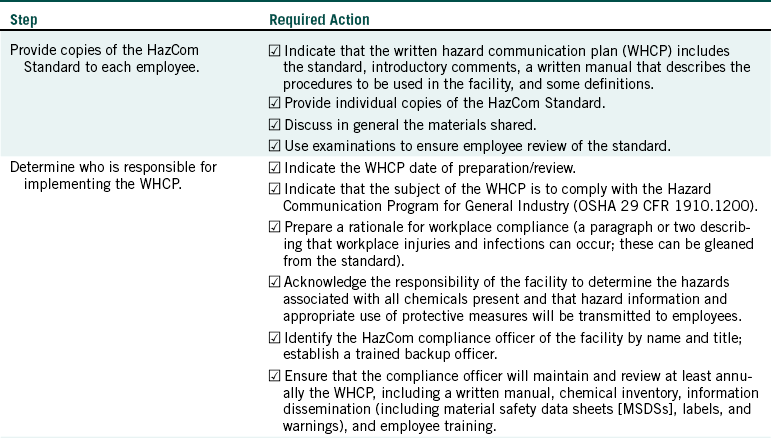

A central activity to meet this goal is the production of a written hazard communication program (see Table 22-1). Although such efforts are usually modest (six to eight pages), they cannot be mere reiterations of the HazCom Standard. They are designed to be manuals that reflect the type and size of the dental practice. Table 22-3 presents an outline of a generic WHCP. Task identification and proper responses follow.

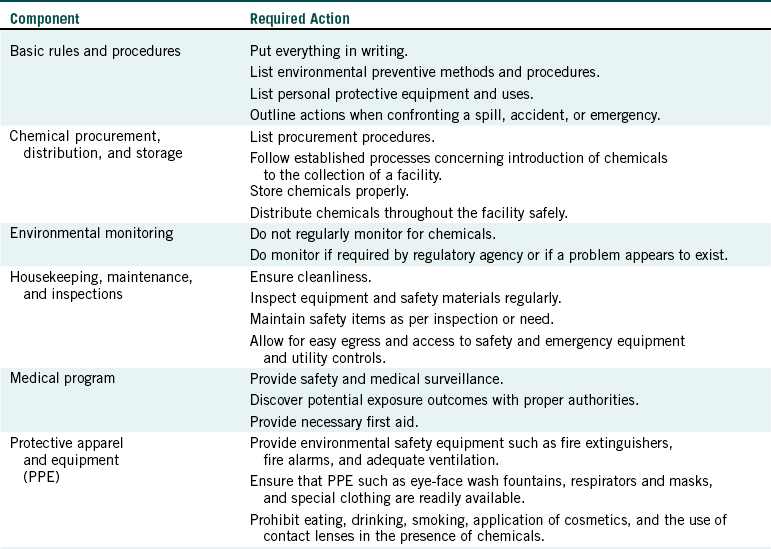

TABLE 22-3

Generic Written Hazardous Chemical Program

Adapted from US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Chemical hazard communication (OSHA 3084), Washington, DC, 1995, US Government Printing Office; and from US Department of Labor, Occupational Health and Safety Administration: Hazard communication; final rule, 29 CFR 1910.1030, Fed Regist 59:6126-6184, 1994.

Employers are required to develop, implement, and maintain (monitor) a WHCP for their workplaces. Minimal contents include a list of all known hazardous materials present, the labeling and warning sign system used, the location and use of MSDSs, emergency procedures, and the nature and frequency of employee information and training. The WHCP helps explain how the clinic/office complies with the various criteria of the standard.

The overall purpose of a WHCP is to provide for the implementation of the requirements of the standard in the workplace and to serve as a reference for employers’ or employees’ questions about official clinic/office policies. Because great differences exist even among clinics/offices in the same general locale, the WHCP must be “personalized” to reflect what actually is being performed.

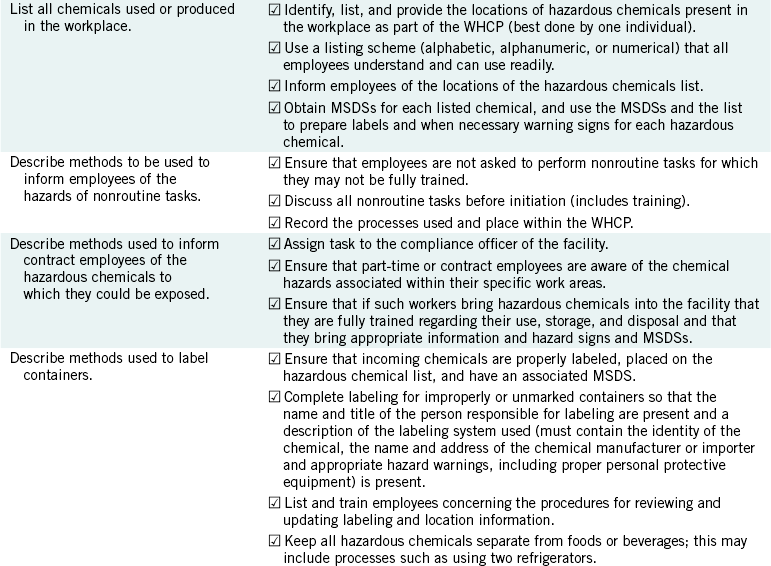

Writing the WHCP involves nine stages or steps:

1. Provide copies of the HazCom Standard to each employee. Familiarity with the standard increases compliance. Employers may devise a modest examination to ensure that employees have read and understood the basic tenets of the standard.

2. Determine who is responsible for implementing the WHCP. The most effective way for a clinic/office to comply with the standard is to identify, train, empower, and reward the HazCom compliance officer (see Table 22-1). A single individual can complete many, if not all, of the various activities associated with HazCom Standard compliance. Compliance is especially important when considering the listing of the hazardous chemicals and the collection of the required MSDSs. The process is improved if a single individual performs all transactions. This person’s name and title must be listed formally. A backup officer (e.g., the dentist) should be identified also.

3. List all chemicals used or produced in the workplace. Specific guidelines on the development of the required list appear later. The compliance officer must review the list often because new chemicals are brought into the clinic/office regularly. The goal is to generate and maintain a complete list and location of all hazardous chemicals.

4. Describe the methods to be used to inform employees of the hazards of nonroutine tasks. Cleaning or repair of some pieces of equipment is an example of nonroutine tasks. Sometimes chemical hazards are released during such processes. In other cases, hazardous chemicals are used during the cleaning or repair. Some office or clinic employees also perform work that does not normally place them at risk for exposure to hazardous chemicals. Such individuals require less information and training.

5. Describe methods used to inform contract employees of the hazardous chemicals to which they could be exposed. Part-time employees or persons hired to clean or repair must be extended the same level of protection as permanent, full-time employees. Contract employees who bring hazardous materials as part of their work into the clinic/office environment must provide appropriate MSDSs.

6. Describe methods used to label containers. This step has three phases:

a. Name and title of the person responsible for the proper labeling of all containers.

b. Describe the labeling system used. (A proper label must contain the identity of the chemical, the name and address of the chemical manufacturer or importer, and appropriate hazard warnings.)

c. Describe the clinic/office procedures for reviewing and updating labeling information.

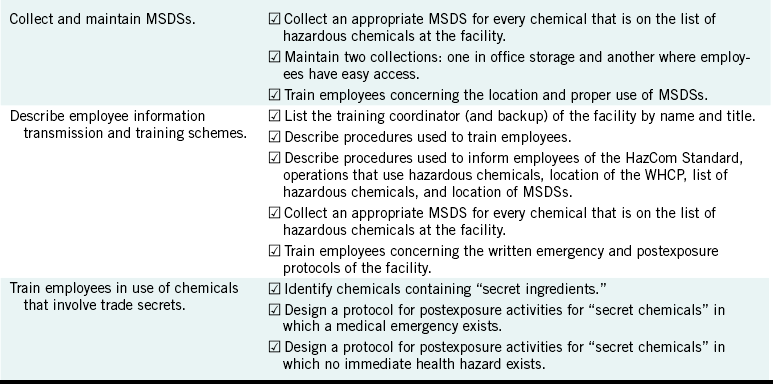

7. Collect and maintain MSDSs. Use of MSDSs is described later. However, MSDSs are the central element for information concerning hazardous materials. The WHCP must describe who is responsible for collecting the MSDSs for each hazardous material and the method used to maintain the MSDS collection (e.g., in notebooks and their locations). Also to be listed are how employees can access MSDSs and how the list of MSDSs is kept current.

8. Describe employee information transmission and training. This step has five phases:

a. Provide name and title of the person responsible for employee training.

b. Describe the procedures used to train employees.

c. Describe the procedures for informing employees of the HazCom Standard, the operations that use hazardous materials, the location of the WHCP, a list of hazardous chemicals, and the location of the MSDSs.

d. Describe the training program, including hazardous materials monitoring, all physical or health hazards present, and measures used to protect employees.

e. Provide details of the WHCP, including an explanation of the labeling system used and how the employees are trained to use MSDSs.

9. Use of chemicals that involve trade secrets. Some chemical manufacturers are reluctant to share information concerning their products because they think that some trade secret could be gleaned. Although the ratios or percentages of the component chemicals can be withheld, the manufacturer/importer has the responsibility to inform the user of the hazardous chemicals. This information includes specific comments as to which protective equipment or processes should be used when handling their product.

After preparation of the WHCP, the compliance office must review it regularly. New employees need to review the WHCP as soon as possible.

INVENTORY AND LISTING OF HAZARDOUS CHEMICALS

Each facility is required to inventory holdings of any hazardous chemicals. Inventories of chemicals can be organized in several ways. Some clinics/offices prefer to use an alphabetic listing; others use a numerical listing in which a chemical is given the next available number. Another method is to organize the chemicals by hazard category. Such divisions usually include corrosive, flammable, reactive, and toxic. No matter which listing process one uses, it must be understood and used properly by employees.

The list can include scientific and common chemical names and even associated hazards. To create an additional column for the PPE and other safety processes to be used for each hazardous chemical is wise. Listing where various hazardous chemicals are located throughout the facility is also useful. Of course, the preparation date (and updates) of the list should be noted prominently. The clinic/office HazCom coordinator should generate and maintain the list. If all purchases and disposals are handled by this individual, there will be little chance that a hazardous chemical will be present but not listed.

Completing a chemical inventory provides an excellent opportunity to discard unwanted chemicals. Such chemicals might be items never used, those past expiration, samples, and those no longer having clinical value. To learn the volume of unwanted chemicals that are present is always a surprise. One always should contact the local environmental regulatory agency concerning proper disposal procedures.

Chemical inventory lists are valuable. All listed chemicals must have their own MSDSs. Lists are also important in the generation of informative signs and warnings and should be used for employee training. All employees must know the location of the list of hazardous chemicals and be able to interpret the information present.

LABELS AND OTHER FORMS OF WARNING

In-house containers of hazardous chemicals must be labeled, tagged, or marked with the identity of the material and appropriate hazard warnings.

Chemical manufacturers and importers and their distributors are required by the HazCom Standard to label properly all products considered hazardous. The minimal acceptable label must include (1) the identity of the hazardous chemical(s), (2) appropriate hazard warning (including target organs or systems and common routes of contact and methods that protect against exposure), and (3) the name and address of the chemical manufacturer, importer, or responsible party.

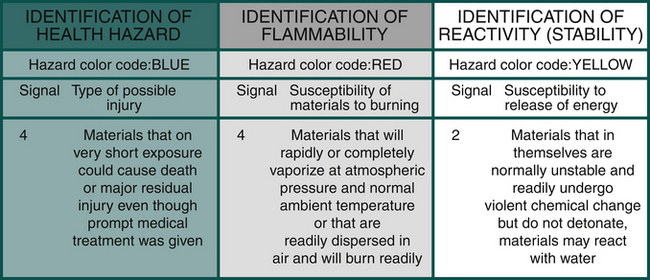

Ideally, the sources of the chemical will label all their containers of hazardous chemicals properly. If an employer determines that a container is labeled properly, the container requires no additional information. One may elect to place extra information (e.g., special labels such as the National Fire Protection Association 704 Diamond System; Figure 22-2) on the container. This could improve the uniformity of the clinic/office labeling system.

FIGURE 22-2 Example of the National Fire Protection Association 704 System diamond identification symbol and description of the various numbers presented.

Unfortunately, some chemicals (especially dental materials kits) are not labeled properly by their sources. In such cases, the clinic/office must complete the labeling process. The clinic/office also must act when a hazardous chemical is removed from properly labeled containers to an improperly (possibly even blank) container. For example, iodophor surface disinfectant is purchased in a concentrated form and then is diluted to its working concentration and placed within spray bottles. The new containers must be labeled with (1) the identity of the hazardous chemical(s), (2) appropriate hazard warning (including target organs/tissues and applicable personal protective equipment and procedures), and (3) the name and address of the chemical manufacturer, importer, or responsible party.

No official labeling system exists. Clinics/offices can photocopy the label from the original container and affix it to the new containers. Several other labeling schemes are available. The most important factors are that the system is easy to use and that employees are trained properly to understand and use the system.

Safe use of hazardous chemicals involves other activities in addition to container labels. Employers can use signs, placards, posted operating procedures, and other written or pictorial information (e.g., international pictograms). Such signage must be in English and when necessary in an alternative language. Warning signs are readily available from many commercial sources. They also, however, can be handmade. The goal is not artistic beauty but simplicity, ease of use, and conveyance of the desired information.

MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEETS

Few safety constructs are more valuable than MSDSs. These are written reports prepared by manufacturers or importers that describe an individual chemical or a group collection of chemicals. Valuable information includes the chemicals present, the associated hazards, handling and cleanup procedures, and special PPE that needs to be in place.

Chemical manufacturers and importers must obtain or develop an MSDS for each product containing hazardous chemicals. This rule applies to single chemicals and multiple-chemical kits. The employer must obtain an MSDS specific for each hazardous chemical present in the workplace. If a clinic/office uses three types of amalgam, three specific (unique) MSDSs are needed. Generic MSDSs are not acceptable. Material safety data sheets contain phone numbers that are answered 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. These contacts are trained to offer highly specific and useful information about the product. Photocopies of MSDSs are acceptable.

Unfortunately, some chemical sources are reluctant, unable, or unwilling to distribute MSDSs, but this does not diminish the requirement of employers to obtain MSDSs for all their hazardous chemicals. Clinics/offices can obtain MSDSs other than from the manufacturer or importer in several ways. Again, a photocopy of an MSDS is as good as an original. In fact, many MSDSs sent with products are actually copies. A small degree of networking among local dental practices (e.g., local study club) can result in a “master list” of MSDSs that can be shared by participants. Many MSDSs are now available on the Internet.

Another difficulty facing clinics/offices is that MSDSs are sometimes incomplete or inaccurate. That is, not all of the nine sections are filled out. One reason is the reluctance of suppliers to describe all chemicals present in their products. Another reason is that if common domain information is not available about a hazardous chemical, the manufacturer or importer must pay to have the product evaluated by a laboratory. Clinics/offices when presented with an incomplete MSDS should write the source for more specific information.

Material safety data sheets must be readily accessible to employees. Ideally, two copies of an MSDS could be kept in notebooks. One set could remain in an office file cabinet; the other could be placed in a general work area, such as the laboratory or instrument recycling room. Material safety data sheets are essential to a successful clinic/office HazCom program.

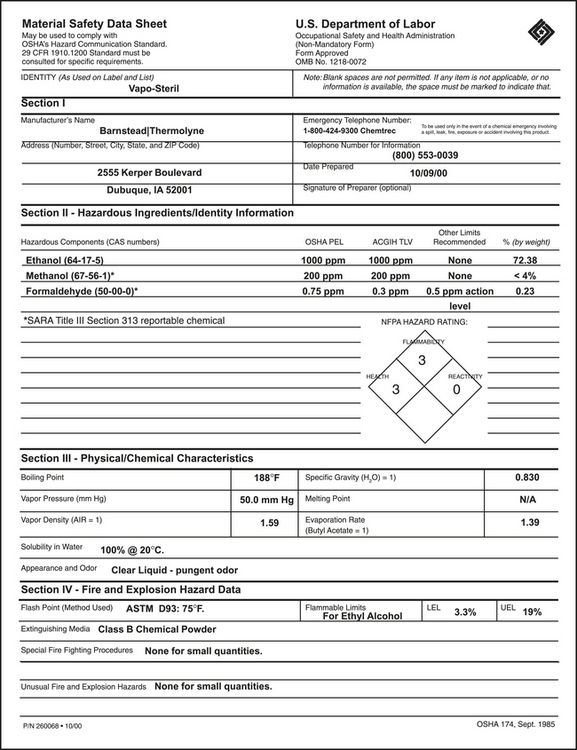

Chemical information presented in MSDSs is essential for the generation of proper labeling and the development of correct warning signs, and notices are present in an MSDS. Emergency exposure guidelines suggest personal protective equipment and mixing; use and disposal tenets are presented also. Figure 22-3 is an example of an actual MSDS.

Material safety data sheets contain nine sections.

1. Product information. The product information section includes the hazardous chemical names, including generic and scientific names. Chemical formulae may also be present. The name, address, and contact phone number(s) are also listed.

2. Hazardous ingredients/identity information. Chemicals known to be hazardous must be listed. Suspected problem chemicals also must be listed, and sometimes hazard data such as flammability, reactivity, or median lethal dose are required. If the concentration of hazardous chemicals is more than 1%, threshold limit values or permissible exposure limits commonly are noted.

3. Physical/chemical characteristics. Although technical, the section on physical and chemical characteristics provides a great amount of useful information. The section describes why the chemical is considered hazardous. Solvents such as ethanol or acetone commonly are used in the dental office, and their hazardous properties are described in this section. Data in this section apply to single, pure chemicals and to combination mixtures of several chemicals. Important physical parameters include terms such as boiling point, vapor pressure, solubility, appearance and odor, specific gravity, vapor density, percent volatile by volume, and evaporation rate. These values are important when dealing with any volatile chemical, that is, a chemical that produces vapors. One should note the levels of acceptable occupational exposures.

4. Fire and explosion hazard data. For flammables, solvents, peroxides, explosives, metal dusts, and any other unstable substances, the information presented in this section is important. If a chemical does not pose a fire hazard, this section should state that. Important terms presented include flash point, flammable liquids (lower explosive limit and upper explosive limit), extinguishing media, and special or unusual fire/explosion procedures and hazards.

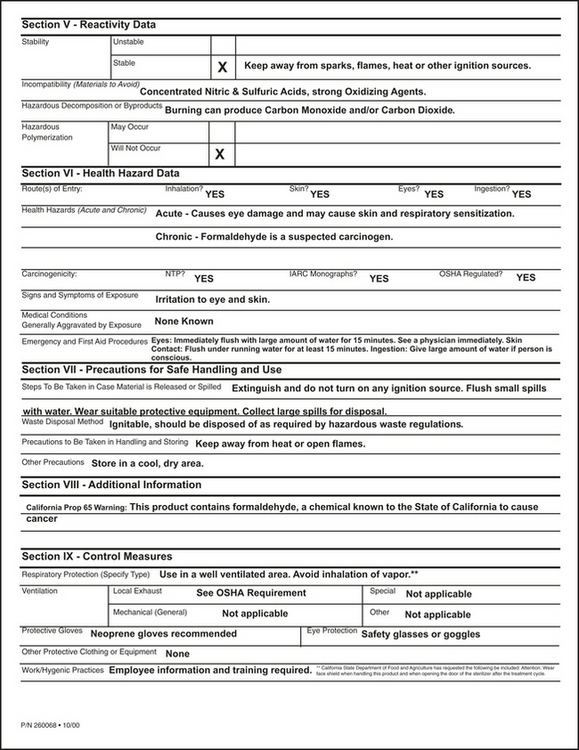

5. Reactivity data. Reactivity data assist one in determining safe handling and storage procedures for hazardous, unstable substances. Adverse reaction (incompatibility) of chemicals with commonly encountered media (e.g., heat, water, direct sunlight, metal piping, and acids/bases) is usually listed. Stability data also are listed in Sections II, IV, and IX. After contamination, aging, or burning, a chemical can decompose into hazardous products. These outcomes also are usually listed. Polymerization of some chemicals can release toxic vapors or high or uncontrolled release of heat, which should be noted.

6. Health hazard information. The health hazard information presented must reflect an estimate of the total product (e.g., after mixing). This information can be expressed as a time-weighted average concentration, permissible exposure limit, or threshold limit value. Sometimes a median lethal dose value is mentioned. Expected routes of exposure also should be listed. Information about the potential hazard from absorption of the product, the severity of the effect, and the basis of the hazard determination must be listed. The positions may come from animal studies or reports of human exposures. The effects of acute and chronic exposure should be discussed and may include some information about the carcinogenic, teratogenic, or mutagenic potential of the chemical. Specific signs and symptoms of exposure should be listed. Emergency and first-aid procedures to be used by trained response personnel also are presented. Often specific notes to physicians are included. If inhalation is the route of exposure, some further comments can be found in Section 3. Section 8 contains information on the proper respiratory equipment (e.g., gloves, eye, and skin protection). This section also discusses the use of protective glasses.

7. Precautions for safe handling and use, including spill or leak procedures. This section gives detailed procedures and protective clothing, equipment, and ventilation to be used for cleaning up a spill and safe disposal of the chemical. Corresponding information can be found in Sections II to VIII. Specific recommendations for cleanup need to be delineated. Also presented is whether the substance is incompatible with common cleanup procedures or media (e.g., water). Sometimes the cleanup residue creates a disposal problem (appropriate final disposal method/site [e.g., sanitary landfill, incineration, or sanitary sewer]). Disposal recommendations also can be found in Sections II, IV, V, and IX.

8. Additional information. This section often lists how to label a container or warning sign properly. Any safety or health information not previously presented is listed. Some chemical sources use this section to reiterate some important safety or health issue.

9. Control measure/special protection information. If required, specific comments about respiratory protection, ventilation, protective gloves, and eye protection are presented. Most of the other sections also contain information about protective methods and materials.

EMPLOYEE INFORMATION AND TRAINING

Employers must provide employees with information and training on all hazardous chemicals present in the workplace, even if an employee does not use some of them in the course of normal work. The employer must provide information and training at the time of an employee’s initial assignment (no matter how experienced or trained the employee may be) or whenever a new hazard is introduced into the work area. To maintain proper clinic/office awareness of hazardous chemicals, annual training sessions are expected.

Employees must be informed of (1) the requirements of the HazCom Standard, (2) any and all operations in the work area where hazardous chemicals are present or are used, and (3) the location and availability of the WHCP, including the required list of hazardous chemicals and collection of MSDSs. As previously stated, for better compliance, each employee must receive a copy of the actual standard as it appeared in the Federal Register.

Training is an essential component of a successful HazCom Standard program. Training is required at the time of hiring, when a new hazard is introduced, and annually for all continuing employees. Training has five major components:

1. How the HazCom Standard is implemented in the workplace. Employees must be trained in the reading and interpretation of labels and MSDSs and how they can obtain and use the available hazard information.

2. Physical and health hazards present. Employers are to be trained about the physical and health hazards associated with hazardous chemicals. The use of MSDSs, container labels, and other forms of warning signs reinforce this process.

3. Personal protective devices. Employees must be informed of and provided with all the personal protective equipment needed to protect them while using hazardous chemicals.

4. Site-specific information. The employer must convey details of the clinic/office WHCP, including an explanation of the labeling system and the MSDS collection, to the employees and must inform employees as to how they can obtain and use appropriate hazard information. Protection includes physical pieces of equipment and specific posted procedures such as appropriate engineering controls, work practice changes, and emergency procedures.

5. Methods and observations. This part of training involves knowledge of the appearance and smell of hazardous chemicals, which helps employees limit exposures to chemicals. This section also assumes that the clinic/office has designed and practiced an emergency plan.

TRADE SECRETS

Chemical manufacturers and importers may withhold specific chemical information, including the chemical name or other specific data that could help identify a hazardous chemical on its MSDS. The central argument is the claim by the source that the information withheld is indeed a trade secret. The rationale is that publication of such information negatively affects market share.

The HazCom Standard attempts to strike a balance between the need to protect exposed employees and a manufacturer’s need to maintain the confidentiality of a bona fide trade secret. Balance is achieved by the source providing, under specified need and confidentiality, limited disclosure to health professionals who are furnishing medical or other occupational health services to exposed employees, employee representatives, or contract workers.

Chemical manufacturers, importers, and in some cases employers must disclose immediately the specific chemical identity of a hazardous chemical to a treating physician or nurse when the information is needed for prompt emergency or first-aid treatment. Companies can request the treating physician or nurse to prepare a written statement of need and to complete a confidentiality agreement after the emergency has abated.

When the case is a nonemergency, the issue can become protracted. A health care professional (e.g., physician, industrial hygienist, toxicologist, epidemiologist, or occupational health nurse) must write the source company, describing the circumstances surrounding the petition.

HOW THE OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION SOLVES A PROBLEM

Of interest is the examination of the thought processes used to solve potentially complex interpersonal problems within the workplace. Successful resolution of questions concerning OSHA compliance and other employee health and safety issues is no exception. For example, an employee on the job for a few weeks begins to complain about feeling ill at work. The employee could state, “I don’t know. Something smells funny in here, and I’m starting to get headaches.” How should this person’s employer best handle the complaint?

Employers must take all employee complaints seriously. Most employees are reluctant to report problems, especially if they seem to involve only themselves. The employer has the responsibility to establish an environment in which employee safety is paramount and in which open communication is the rule. Dismissing out of hand an employee complaint is unfair and unwise. Employees who think their reasonable requests are not being addressed properly are far more likely to seek an answer outside of the office or clinic. In other words, the chances of them reporting the case to a regulatory agency are greatly increased.

The first action the employer should take is to determine whether a request is reasonable. This is probably more difficult than it sounds. Some employees at times make and maintain unreasonable requests. Fortunately, such cases are the exception. However, separation may be the only viable answer in extreme situations. A guiding rule as to whether a request or a policy, procedure, or piece of equipment has validity is to subject it to three challenges: “Is it reasonable?” “Is it necessary?”, and “Is it appropriate?”

Employers must do what is required and proper, but they are not obligated to provide more than what is necessary. Regular clinic/office meetings at which compliance issues are discussed in an open manner are central to clinic/office morale and compliance. After such discussions a decision should be made quickly. If the answer is “no,” the logic behind the position should be presented. Because the employer is responsible for employee safety, the employer makes the final decision. However, employees usually expect and wish to be active participants in the process. Employers must provide a working environment that is safe; the employees have the responsibility to comply with established clinic/office procedures.

If after careful review an employer decides that an employee complaint has merit, remedial action is required. This does not mean necessarily that just because an odor is present, the odor is causing the employee’s headaches or that it is indeed even potentially harmful. The employer has an obligation to investigate the matter further. Of course, the first temptation is to provide personal protective devices, such as masks. When presented with such a scenario, OSHA would consider its resolution to be a four-step process that progresses from more effective actions to those less effective. The steps are as follows:

1. Determine whether a problem exists. The presence of an odor may or may not indicate a potential problem. Of course, some dangerous chemical vapors have little or no odor. Some types of monitoring devices, such as air samplers attached to color change chemicals or spectrophotometric devices, may be required. Other chemicals can be monitored easily with the use of inexpensive badges. Persistent problems may require consultation with an industrial hygienist or the local health or air quality department. Fortunately, in most cases, no problem exists or it is solved readily. Problems, of course, can involve issues such as air quality, sound, heat, and lighting (e.g., curing lights).

2. Engineering controls. Engineering controls are measures designed to isolate or remove the chemical hazard from a workplace. If a problem exists, OSHA indicates that the most effective and efficient method of resolution is to remove or change the chemical used or somehow to use it differently. A common dental example is a glutaraldehyde solution. All sterilizing chemicals are harsh at room temperature and easily can generate irritating fumes, which could cause allergies. Direct contact with unprotected skin or mucous membranes likely would lead to complaints and possible injury. If an employee complains about the use of glutaraldehydes, the best option is to change how reusable instruments and equipment are sterilized. This change could include a change to a heat treatment process such as autoclaving. If the items are heat sensitive, other glutaraldehyde solutions are commercially available. A change in the chemical used could help eliminate the problem.

3. Work practices. Work practice controls are methods that reduce the likelihood of exposure by altering the manner in which a chemical is used. If engineering controls cannot be used because the chemical is absolutely necessary, the employer should investigate using work practice controls. Again, using glutaraldehyde as an example, such solutions usually can be used safely when present in small amounts and when held within tightly sealed containers. Ideally, removing or changing the chemical is the most effective process. However, if the chemical must be used, workplace practices may have to be changed significantly. Of course, an increase in ventilation, such as using a fume hood, is always beneficial.

4. Personal protective equipment. Personal protective equipment includes specialized clothing or equipment worn by an employee for protection against a chemical hazard. General work clothes usually are not sufficiently protective. For several reasons PPE is considered to be the least effective and efficient method to prevent employee exposures. One major deficiency is the lack of universal application. One cannot expect that employees always will wear the proper equipment whenever the hazard is present, including accidents. Obviously, PPE must be in place whenever any risk of exposure exists. Another fault of PPE involves the physical nature of barriers. Eventually all barriers fail. With newer designs and fabrication materials have improved the longevity of some PPE. Technological advances also have helped to improve overall barrier performance. Unfortunately, personal protective barriers will never be as effective as removing or changing a hazardous chemical or the use of improved handling methods.

OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE TO HAZARDOUS CHEMICALS IN LABORATORIES

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has promulgated a safety standard (29 CFR Part 1450, Occupational Exposure to Hazardous Chemicals in Laboratories) that helps protect employees engaged in the laboratory use of hazardous chemicals (Table 22-4).

TABLE 22-4

Important Definitions for a Chemical Hygiene Plan

| Term | Definition |

| Action plan | Includes concentrations designated in 29 CFR part 1910 for a specific substance as being safe, calculated on an eight-hour average exposure. Action plan usually is constructed in response to a complaint or is part of the regular review program of the facility. Appropriate responses include exposure monitoring and medical surveillance. |

| Chemical hygiene officer | An employee who is designated by the employer and who is qualified by training or experience to provide technical guidance in the development and implementation of a chemical hygiene plan. For clinical dentistry, the position is similar to the office infection control hazard communication officer. |

| Chemical hygiene plan | A written program developed and implemented by the employer that sets forth procedures, equipment, personal protective equipment, and work practices that (1) are capable of protecting employees from health hazards presented by hazardous chemicals used in a particular workplace and (2) involve the application of the tenets of “prudent practice.” |

| Emergency | Any occurrence such as equipment failure, rupture of containers, or failure of control equipment that results in the uncontrolled release of a hazardous chemical into the workplace. |

| Hazardous chemical | A chemical for which statistically significant evidence based on a scientifically designed and conducted study indicates the acute and chronic health effects that may occur to exposed employees. Many of the chemicals used within dental offices/clinics are considered hazardous. |

| Prudent practices | Originally developed in 1981 by the National Research Council, this plan is useful for preparing a workplace chemical hygiene plan. The plan helps to organize identified hazards better and offers recommendations for each type of hazard and deals with safety and chemical hazards; the Laboratory Standard is concerned primarily with chemical hazards. |

Adapted from Occupational Safety and Health Administration: 29 CFR Part 1450: Occupational exposure to hazardous chemicals in laboratories standard and Standard Appendixes A and B, Washington, DC, 1990, US Government Printing Office.

In many ways, dental offices and clinics function as laboratories. Although carcinogenic, radioactive, or extremely toxic materials are rarely present, dental workplaces contain significant amounts and varying types of hazardous chemicals. Employees routinely prepare, use, store, and dispose of these materials, in addition to being exposed daily to infectious agents and physical methods of harm (e.g., heat, sound, light, and air quality).

The major objective of the standard is to limit employee exposures to specific permissible levels when working in laboratories. For some chemicals, other OSHA and EPA standards apply that are stricter. In some cases, absolutely no exposure is permitted. Some chemicals, however, are exempt. These include chemicals that have no potential for employee exposure; for example, (1) procedures that use chemically impregnated test media (dipsticks) that are placed into liquid specimens and then the amount of color changed is observed and (2) commercial kits in which all the reagents needed to conduct a test are contained within the kit (a pregnancy test is an example).

Limits are not known for all individual chemicals or for groups of chemicals mixed to create a new end product. However, complaints about odors, headaches, runny noses and eyes, nausea, or skin hypersensitivities are common. The initial response is to determine whether a problem actually exists.

COMPLIANCE

Compliance with the Safe Use of Chemicals in the Laboratory Standard involves seven sections or components: (1) general principles, (2) responsibilities, (3) laboratory facility, (4) components of the chemical hygiene plan, (5) general principles of working with chemicals, (6) safety recommendations, and (7) material safety data sheets. This organization of topics corresponds to sections in the standard and the recommendations made in Appendixes A and B of the standard. Compliance is mandatory for the standard; however, the materials presented in Appendixes A and B do not have to be followed exactly as presented. These appendixes offer valuable organizational help and make valid suggestions. Reviewing (and possibly using) these materials may help any clinic/office compliance program greatly.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR WORKING WITH LABORATORY CHEMICALS

Each workplace must develop an appropriate chemical hygiene plan (see Table 22-4). No official form or format exists. However, information given in Appendixes A and B of the Laboratory Standard helps make compliance an easier and more effective process.

Many of the recommendations offered follow those provided by the National Research Council (1981). These recommendations often are called Prudent Practices for Handling Hazardous Chemicals in Laboratories or simply prudent practices (see Table 22-4). The practices actually are an assessment of risk and a listing of recommendations that have the ultimate goal of limiting workplace exposure to harmful chemicals. Prudent practices have a broader scope or intent than the Laboratory Standard. Prudent practices deal with safety and chemical hazards, whereas the Laboratory Standard is concerned primarily with chemical hazards.

Minimization of all exposures to chemicals is prudent. General precautions for the use of chemicals should be developed and implemented effectively. Written general precautions are usually more valuable than the generation of specific guidelines for particular chemicals. An analogy is the concept of universal precautions. In this case, the objective is to prevent contact of health care workers with patient body fluids. The combination of engineering controls, work practices, and PPE selected should protect against any infectious agent present in blood and other body fluids.

One should not underestimate risk. Even for chemicals that seem to have little or no toxicity, exposure always should be kept to a minimum. Of course, chemicals known to cause problems require special handling. Information on use may come from the manufacturer/importer and is present on the MSDS. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration also can provide lists of chemicals that indicate their relative toxicity and acceptable levels of employee exposures. Minimization of exposure also involves an action plan (see Table 22-4) that is a determination of the levels of chemicals present in the workplace over a specific time and then the generation of an appropriate response.

One of the most effective ways to minimize employee exposure is to limit release and to dilute with air any emissions. Adequate ventilation must be provided and may include fume hoods and other ventilation devices.

A central activity for compliance with the Laboratory Standard is the mandatory preparation of a chemical hygiene plan designed to minimize exposures. This plan always should be considered “as a work in progress,” should address all salient issues, and should be in writing.

CHEMICAL HYGIENE RESPONSIBILITIES

Every person working at a location is responsible for chemical hygiene. The chief executive officer is ultimately responsible; however, all employees must understand the Laboratory Standard and comply with its tenets.

One way to deal with the requirements is to appoint a chemical hygiene officer (see Table 22-4) who can serve as liaison between employees and management. Responsibilities include (1) monitoring procurement, use, and disposal of laboratory chemicals; (2) maintaining lists of chemicals present; (3) being aware of current exposure limits for the chemicals present; and (4) working with management continually to improve the chemical hygiene plan.

The chemical hygiene officer in a dental office or clinic also may serve as laboratory supervisor. The responsibilities of this individual include (1) ensuring that workers know and follow chemical hygiene rules; (2) ensuring that proper PPE and other types of protective equipment are present and in working order; (3) performing necessary inspections; (4) keeping up to date on current legal requirements concerning regulated substances; (5) evaluating and selecting protective apparel and equipment; and (6) ensuring that the facility and the workers are prepared (usually through training) for the use of a new chemical.

Workers are responsible for planning and conducting each operation according to the chemical hygiene procedures of the office/clinic, which usually involves a “safety first” philosophy. Workers must comply with the tenets of the Laboratory Standard as presented in the written plan of the facility.

LABORATORY FACILITIES

Laboratories should have an adequate general ventilation system. In some cases, special air exhaust equipment (e.g., ventilation hood) is needed. Personal protective equipment more commonly is required. Proper air circulation is needed in all areas of the facility. The best setup is to have an eye-face wash fountain and a sink readily available when handling hazardous chemicals. Having more than one fountain or sink may be necessary. Each facility also should have a formal procedure for the disposal of waste chemicals.

To have the ventilation, exposure control, and PPE materials functioning properly, significant attention must be paid to their maintenance, performance, and applicability. Having the equipment and materials checked by an outside sales and service company may be necessary.

CHEMICAL HYGIENE PLAN

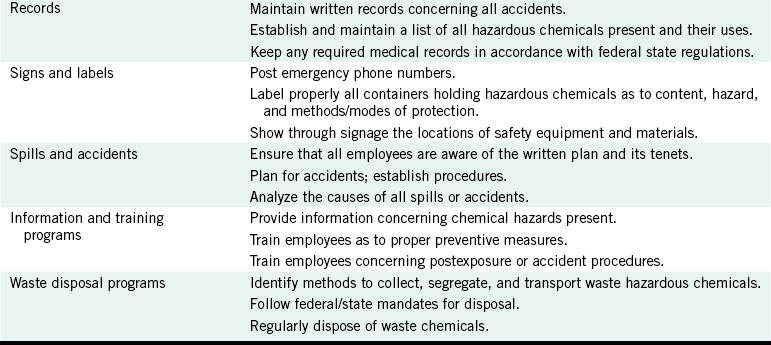

A chemical hygiene plan is the central element for compliance with the Laboratory Standard. The plan should be in writing and begins with a listing of the basic rules and procedures to be used in a facility (Table 22-5). Specific comments on chemical procurement, distribution, and storage and disposal of chemicals follow.

TABLE 22-5

Components of a Chemical Hygiene Plan

Adapted from Occupational Safety and Health Administration: 29 CFR Part 1450: Occupational exposure to hazardous chemicals in laboratories standard and Standard Appendixes A and B, Washington, DC, 1990, US Government Printing Office.

Regular instrument monitoring usually is not required. However, such tests can help determine whether a problem exists and what changes are needed.

Proper housekeeping, regular maintenance, and periodic inspections need to be performed. Clean floors and surfaces enhance safety. Inspections can identify needed maintenance. For example, eye-face wash fountains should be inspected every 3 months. Other pieces of equipment also can be inspected at regular intervals. Methods of egress and access to emergency equipment and utility controls in the event of an emergency (see Table 22-5) must be available. Passageways, stairways, and hallways must not be used as chemical storage areas.

Each office or clinic must be prepared to provide a medical program, which may involve regular surveillance. More commonly present is the need for first aid, which includes in-house and emergency room activities. Protective apparel and equipment needed include PPE that is compatible with the required degree of protection for the substances being handled, an eye-face wash fountain, fire extinguishers, respiratory protection (including dust), fire alarms, emergency phone numbers, and any other items chosen by the chemical hygiene officer.

Certain records need to be kept to be in compliance. A written record of all accidents must be retained. Because federal and state agencies differ on how long such records need to be kept, one should consider their storage as permanent. The office or clinic plan should be reviewed regularly and changed when necessary. Chemical inventory and use records for hazardous chemicals also should be completed.

One of the most effective safety processes is the placement of signs and labels. Such items need to be posted prominently; the four categories are (1) emergency telephone numbers (in-house and community rescue), (2) labels that show the contents of containers (including waste receptacles) and associated hazards, (3) location signs for eye-face wash fountains and other safety and first-aid equipment and areas where food and beverage consumption and storage are permitted (e.g., refrigerators), and (4) warnings at locations where special or unusual hazards are present.

Accidents and spills should be uncommon events. However, planning and practice of the plan should minimize employee exposure to harmful chemicals. The written chemical hygiene plan must be communicated to each employee and provide procedures for evacuation, medical care, incident reporting, clean up (spill control), and drill. Some type of alarm system is helpful. The purpose of a training program is to ensure that all individuals at risk are informed adequately about working in the laboratory, its risks, and what to do if an accident occurs, including first aid and the use of special chemical abatement equipment.

A proper waste disposal system helps ensure minimal harm to persons, other organisms, and the environment from the disposal of waste laboratory chemicals, including collection, segregation, and transportation. An office or clinic must follow local regulations when disposing of chemicals. Waste should be removed regularly. Indiscriminate disposals, such as pouring down a drain or mixing of chemicals with other refuse and placement in landfills, are unacceptable.

WORKING WITH CHEMICALS

A chemical hygiene plan requires workers to know and follow safety rules and procedures. Methods designed to avoid chemical contact must be followed regularly. In the event of an exposure, prompt action is necessary. Extended flushing of eyes with water (usually for 10 to 15 minutes) followed by medical attention is an example. Water rinsing and removal of soiled clothing helps minimize skin contact. Obviously, planning for accidents is essential. One must assume that exposures will occur, and an effective and efficient response is essential.

Preventive behaviors are also helpful. Personnel must avoid eating, smoking, drinking, gum chewing, and applying of cosmetics in the presence of hazardous laboratory chemicals. Segregation of chemicals from foodstuffs is imperative. Having two refrigerators, one for food and the other for chemicals, may be necessary. Some types of contact lenses adsorb chemical vapors. One should avoid the use of contacts unless necessary.

SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS

Safety is a two-part equation: prevention and proper handling of accidents and emergencies. If precautions fail, the chances of exposures increase. Working hard to prevent injuries is always better than managing exposures.

Indiana Department of Labor. Bureau of Safety Education and Training: Guidelines for developing a written hazard communication program. Indianapolis: State of Indiana; 1992.

Indiana Department of Labor. Bureau of Safety Education and Training: How to read and understand a material safety data sheet. Indianapolis: State of Indiana; 1991.

Meyer, E. Chemistry of hazardous materials, ed 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1989.

Miller, C.H. Chemical reaction. Dent Prod Rpt. 2007;41:110. 112-114

Miller, C.H., Palenik, C.J. Sterilization, disinfection and asepsis in dentistry. In: Block S.S., ed. Disinfection, sterilization and preservation. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1049–1068.

Office of the Federal Register. National Archives and Records Administration: CFR 29 Part 1900-1910.99. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1996.

Palenik, C.J., Miller, C.H. All about OSHA, part I. Dent Asepsis Rev. 1997;18(6):1–.2.

US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Hazard Communication Rule, 29 CFR 1910.1200. Federal Standards and Interpretations 1991;806. 15-806-31

US Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Hazard communication; final rule, 29 CFR 1910.1030. Fed Regist. 1994;59:6126–6184.

US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Chemical hazard communication (OSHA 3084), Washington, DC, 1998, US Government Printing Office. Also retrieved September 2003 from www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3084.pdf.

US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Safety and health topics: hazard communication. Retrieved September 2003 from www.osha.gov/SLTC/hazardcommunications/index.html.

Review Questions

______1. Chemical-resistant gloves are an example of:

______2. Who determines the hazards of a chemical?

______3. In the 704 System of the National Fire Protection Association, the blue section is for communicating __________________ hazards.

______4. Material Safety Data Sheets have __________________ sections.

______5. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the most effective way to solve a problem is: