Philosophical Foundations

Although you do not have to be a philosopher to engage in the research process, it is important to understand the philosophical foundations and assumptions about human experience and knowledge on which experimental-type, naturalistic research and, more recently, mixed methods traditions are based. By being aware of these assumptions, you will be more skilled in directing the research process and in selecting specific methods to use and combine. Also, an understanding of these philosophical foundations will help you recognize that “knowledge” is shaped by the way you frame a research problem and the strategies that are used to obtain, analyze, and interpret information.

The questions, “What is reality?” (ontology) and “How do we come to know it?” (epistemology) have been posed by philosophers and scholars from many academic and professional disciplines throughout history. As we have suggested, in Western cultures, until recently, there have been two primary but often competing views of reality and how to obtain knowledge. These two perspectives reflect the basic differences between naturalistic inquiry and experimental-type research. Logical positivism is the foundation for deductive, predictive designs that we refer to as “experimental-type research.” In contrast, a number of holistic and humanistic philosophical perspectives use inductive and abductive reasoning, which form the foundation for the research tradition that we refer to as “naturalistic inquiry.” The third view, which transcends the seeming incompatibility of these philosophical positions and provides a sound rationale for using mixed methods, is pragmatism.

Philosophical foundations of experimental-type research

Experimental-type researchers share a common frame of reference or epistemology that has been called rationalistic, positivist, reductionist, or logical positivism. Although theoretical differences exist between these terms, we use the term “logical positivism” to name the overall perspective on which deductive research design is based.

Descartes, a 17th-century philosopher, is often considered the father of Western philosophy. He proposed dualism, an idea that divided the mind and the body into distinct entities. Building on Cartesian thinking, David Hume, an 18th-century philosopher, was most influential in developing this traditional theory of science,1 which posited a separation between individual thoughts and what is real in the universe outside ourselves. That is, traditional theorists of science define “knowledge” as part of a reality that is separate and independent from individuals and that is verifiable through the scientific method. These theorists believe the world apart from our ideas and a single truth are real, objectively knowable, and can be discovered through observation and measurement that, if properly conducted, is considered unbiased. This epistemological view is based on the fundamental assumption that it is possible to know and understand phenomena that reside outside ourselves, separate from the realm of our subjective ideas. Only through observation and sense data, defined as information obtained through our senses, can we come to know truth and reality.

Philosophers in subsequent centuries further developed, modified, and clarified Hume's basic notion of empiricism to yield what today is known as logical positivism. Essentially, logical positivists believe that there is a single reality that can be discovered by reducing it into its parts, a concept known as reductionism. The relationship among these parts and the logical, structural principles that guide them can also be discovered and known through the systematic collection and analysis of sense data, finally leading to the ability to predict phenomena from what is already known. Bertrand Russell, a 20th-century mathematician and philosopher, was instrumental in promoting the synthesis of mathematical logic with sense data.2

Statisticians, such as Quetelet, Fischer, and Pearson, developed theories to reveal “fact” (elements of knowledge that is considered to be real) logically and objectively through mathematical analysis. The logical positive school of thought therefore provided the foundation for what most laypersons have come to know as “experimental research.” In this approach, a theory or set of principles is held as true. Specific areas of inquiry are isolated within that theoretical perspective, and clearly defined hypotheses (expected outcomes of an inquiry that investigate only those phenomena) are posed and tested under carefully controlled conditions. Sense data are then collected and mathematically analyzed to support or refute hypotheses. Through incremental deductive reasoning, which involves theory verification and testing, “reality” can become predictable.

Another major tenet of logical positivism is that objective inquiry and analysis are possible; that is, the investigator, through the use of accepted and standard research techniques, can eliminate bias and achieve results through objective, quantitative measurement.3–6

Philosophical foundations of naturalistic inquiry

Another school of theorists has argued an alternative position: individuals create their own subjective realities, and thus the knower and knowledge are interrelated and interdependent.7–9 In general, these theorists believe that ideas and individual interpretations are the lenses through which each individual knows the universe and that we come to understand and define the world through these ideas and our unique interpretation of symbols. Furthermore, within these traditions, there is a range of beliefs about the stability of ideas, symbols, and the role of language in communicating or even creating ideas and experiences. These epistemological viewpoints are based on the fundamental assumption that it is not possible to separate the outside world from an individual's ideas, language, symbol, and perceptions of that world. Knowledge is based on how the individual perceives experiences and how he or she understands his or her world. A number of research strategies share this basic holistic, epistemological view, although each is rooted in a different philosophical tradition.

Although research based on the understanding that there are pluralistic perspectives has gained acceptance more recently than logical positivist approaches, the philosophical perspectives are not new. Ancient Greek philosophers struggled with the separation of idea and object, and philosophers throughout history continue this debate.10 The essential characteristics of what we refer to as pluralistic philosophies are as follows:

1. Human experience is complex, holistic, and cannot be understood by reductionism, that is, by identifying and examining its parts.

2. Meaning in human experience is derived from an understanding of individuals in their social, economic, political, cultural, linguistic, physical, and virtual environments.

3. Multiple realities exist, and our view of reality is determined by events viewed through individual lenses or biases.

4. Those who have the experiences are the most knowledgeable about them.

In addition to these common characteristics, pluralistic philosophies encompass a number of principles that guide the selection of particular designs in this category. For example, phenomenologists believe that human meaning can be understood only through experience.8 Thus, a phenomenological understanding is limited to knowing experience without interpreting that experience. In contrast, interpretive and social “semiotic” interactionists assume that human meaning evolves from the context of social interaction.8,11,12 Human phenomena can therefore be understood through interpreting the meanings in social discourse, exchange, and symbols. Deconstructionists focus on the primacy and fleeting stability of language, and thus research based on that philosophical thought examines how language both forms and undermines what we know.13 These philosophies therefore suggest a pluralistic, holistic view of knowledge; multiple realities can be identified and understood to a greater or lesser extent only within the natural context in which human experience and behavior occur. To the extent possible, coming to know these realities requires a research design that investigates phenomena in their natural contexts and seeks to discover complexity and meaning. Furthermore, those who “own” or have the experience are considered the “knowers,” and they transmit their knowledge through doing and telling.11

Implications of philosophical differences for design

The previous discussion provided the basic elements of different philosophical positions concerning how we think about and develop an understanding or knowledge about human life. Although you do not have to take a position on the ongoing debate between different philosophical positions, it is important to recognize that by adapting a particular methodology, you are implicitly adhering to a particular way of viewing the world and knowledge development. You may also find yourself gravitating to a particular research approach because you feel more comfortable with it or because it may resonate with how you see the world. How you explicitly or implicitly define and generate knowledge and how you define the relationship between the knower (researcher) and the known (research outcomes or phenomena of the study) will direct your entire research effort, from framing your research question or query to reporting your findings. Let us consider some examples of these important philosophical concepts and their implications for research design.

Suppose that three researchers want to know what happens to participants in group therapy who have joined the group to improve their self-confidence. The researcher who suggests that knowing can be objective may choose a strategy in which he or she defines “self-confidence” as a score on a preexisting, standardized scale and then measures participants' scores at specified intervals to ascertain changes. Changes in the scores suggest what changes the group has experienced.

A second investigator, who believes that the world can be known only subjectively, may choose a research strategy in which the group is observed and the members are interviewed to obtain their perspective on their own progress within the group.

A third investigator, who believes that language shapes individual perception of reality, will focus on analysis of language communication and its multiple uses, contexts, and meanings within the group setting.

A fourth researcher, who believes in the value of many ways of knowing, may integrate the previous three strategies. This researcher tries to understand change from the communication patterns as well as individual perspectives of the participants and from the perspective of existing theory as measured by a standardized self-confidence scale.

Research traditions

Thus far, we have focused on two primary philosophical traditions that underpin two broad categories of inquiry. We categorize these research approaches as experimental-type and naturalistic inquiry. Within each of these categories are many systematic research strategies. We suggest, however, that for the most part, research strategies fall within two primary research traditions.

The first tradition shares the philosophical foundation of experimental-type research. In this tradition, a prescribed sequence of linear processes (as discussed in detail in subsequent chapters) is designed and implemented.4,6 Throughout this text, we refer to this tradition as “experimental-type research.”

In contrast, strategies that share the principles of a holistic pluralistic perspective or naturalistic inquiry follow a nonlinear, iterative, and flexible14 sequence of processes. Throughout this text, we include these strategies in the tradition of “naturalistic inquiry.”

Each design tradition has its own language, its own thinking and action processes, and specific design issues and concerns. We use the concept of the two traditions throughout this text as a basis from which to discuss and compare design essentials and research processes within the same philosophical perspective and across philosophical traditions. We visit mixed methods later as the integration of these two research traditions. However, because experimental-type and naturalistic inquiry form the basis for what strategies are used in mixed methods, we suggest that one must become conversant in each of the primary traditions to understand and efficaciously use mixed methods.

Experimental-Type Research

Let us begin with the philosophical foundation of the experimental-type tradition. First, remember that logical positivists believe that there is a single reality and that one can come to know it through a deductive process. This process involves theorizing to explain the part of reality about which the investigator is concerned, reducing theory to observable parts, examining the parts through measurement, and determining the degree to which the analysis verifies or falsifies part or all of the theory. Second, a central principle of logical positivism is that it is possible and desirable to understand the world through systematic objectivity and by eliminating bias in our observations. Given these two critical elements of logical positivism, let us examine how each research essential, as it occurs in a linear sequence, supports the tenets of logical positivist inquiry.

After identifying a philosophical foundation, the researcher begins by articulating a topic of inquiry. Think back to our example in Chapter 1 in which disparities to Web-based health information was the topic of interest. We name this step “framing the problem,” which identifies and delimits the part of the “real world” that an investigator will examine. After a research problem is identified, supporting knowledge is obtained by conducting a review of scholarly literature and resources. This research essential discerns how the problem has already been theoretically approached and explained. It examines the extent to which the theory has been objectively and rigorously investigated. The scholarly review of literature and other sources of knowledge therefore provide the researcher with knowledge for developing a theoretical foundation for the inquiry. With this information, the investigator is now ready to propose a specific research question. This question is derived from and builds on previous inquiry, isolates the theoretical material to be scrutinized, and incrementally advances knowledge about the subject under study. The ultimate goal is to predict a part of reality from knowing about other parts. To answer the research question objectively, the investigator selects a research design that answers the research question and controls factors that introduce bias into a study. The design clearly and succinctly specifies all action processes for collecting and analyzing information so that the study may be replicated by other investigators. To ensure that the goals of objectivity and the elimination of bias are met, these actions must be followed exactly as designed. Through data analysis, the investigator examines the extent to which the findings have objectively confirmed or raised doubts about the “truth value” of the theoretical tenets and their capacity to explain and ultimately predict the slice of reality under investigation.

Many designs are anchored in the philosophical foundation of logical positivism. Box 3-1 lists the four major categories of design that form the experimental-type tradition, each of which is discussed in detail in Part III of this text.

Naturalistic Inquiry

There is great diversity in the strategies that are categorized as naturalistic inquiry. As indicated in this chapter, designs that fit with this tradition are rooted in different philosophical and theoretical perspectives. The language and thinking processes used by naturalistic researchers vary within the tradition and are significantly different from the language and thinking processes found in the experimental-type tradition. However, all naturalistic approaches have characteristics in common and rely primarily on qualitative methodologies, although often for different purposes and often to answer distinct types of inquiries.

These designs vary according to (1) the extent to which inquiry involves the personal “essence,” language, experiences, and insights of the investigator; (2) the extent to which individual “experience” and meaning versus patterns of human experience is sought; (3) the extent to which the investigator imposes structure in the data collection and analytical processes; and (4) the sequence of the research process.

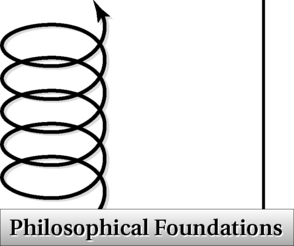

Neither the point of entry into the spiral of inquiry nor the sequence of the thinking and action processes is prescribed a priori. Thus an investigator may begin with any of the essential thinking and action processes, change the design or specific action strategies in response to findings throughout the research process, and revisit steps that have already been conducted. Many methodologists use the term “iterative” to describe the repetitive, flexible, and progressively building process of naturalistic inquiry.14

Although there are many design variations, Box 3-2 lists the major categories of design that make up the tradition of naturalistic inquiry, as discussed in detail in Part III.

Integrating the two research traditions

As briefly discussed, there has been significant and heated debate over which research tradition is most efficacious in advancing our understanding of human experience. Because experimental-type researchers believe that reality can only become known incrementally through implementing objective thinking and action processes, they may not value the naturalistic foundations of pluralism and subjectivity. Conversely, many naturalistic researchers question the extent to which human experience can be reduced to a single, observable, and predictive reality. Moreover, because of the philosophical differences between the traditions, many scholars and researchers have suggested that the two cannot be integrated because of philosophical incompatibility.

Most recently, however, there is a growing movement in both traditions to recognize the strengths and values of the other.15,16 Experimental-type methodologists have begun to recognize that naturalistic inquiry represents a legitimate and logical alternative research strategy to experimental-type inquiry, and naturalistic researchers are giving greater attention to the standardization of analysis and procedures and to the complementary role of experimental-type designs. Consistent with a growing number of methodologists, we believe that the following eight points of tension in the health and human service research world have led many investigators to eschew the traditional opposition of qualitative-quantitative research in favor of strategies that overcome or transcend the limitations of each research tradition.

1. The focus on the experimental-type tradition as the only viable research option has been brought into question by findings that repeatedly indicate little or no measurable effects of experimental treatments in health and human service research.

2. Multiple explanatory theories can enrich knowledge, and thus strategies that rely on a single truth can limit rather than expand knowledge.

3. There is growing recognition that many of the persistent and unanswered issues that are critical to health and human services cannot be answered by the experimental paradigm alone.

4. There is an increasing realization that quantitative information, in and of itself, does not necessarily provide insight to the various processes that underlie the “hard facts” of a numerical report.

5. There are often great discrepancies in knowledge generated from qualitative and quantitative studies.

6. The increasing emphasis placed on the empirical demonstration of the need for outcomes of health and human services has led naturalistic researchers to consider using replicable strategies.

7. Understanding and eliminating disparities in health and wellness among diverse population groups require the use of multiple discovery and verification strategies.

8. Within naturalistic design, the limits of relativism in predicting outcomes can be redressed and ameliorated by purposive addition of experimental-type measurement to qualitative strategies.

Both traditions have strengths and limitations; both have value in investigating the depth and breadth of research topics that inform us about human experience; and both can be integrated in a single study or throughout all or some of the parts of a research project involving multiple studies. We suggest that an integrated approach can strengthen health and human service inquiry. An integrated approach involves purposively selecting and combining designs and methods from both traditions so that one complements the other to benefit or contribute to an understanding of the whole.

However, as discussed throughout this text, efficacious integration is contingent on an investigator's firm understanding of the strengths and limitations of the thinking and action processes, the design strategies, and the particular methodological approaches of each tradition. Given this understanding, the investigator can mix and combine strategies to strengthen the research effort and to strive for comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under consideration. In their classic work, Brewer and Hunter used the term multimethod research and explain the premise of this approach to inquiry in this way:

Our individual methods may be flawed, but fortunately the flaws in each are not identical. A diversity of imperfection allows us to combine methods not only to gain their individual strengths but also to compensate for their particular faults and limitations. Its [multimethod research] fundamental strategy is to attack a research problem with an arsenal of methods that have nonoverlapping weaknesses in addition to their complementary strengths.17

The integration of the research traditions as a way to strengthen and advance scientific inquiry has a 35-year history in sociology, anthropology, and education. Only more recently, however, has the integration of the traditions become acceptable and even popular in health and human service research. Many researchers implicitly use one or more forms of integration discussed throughout this text. For example, there is a long history of the use of simple descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and means, in ethnographic research, and quantitative studies frequently use an exploratory, open-ended series of questions before establishing closed-ended and numerically based interview questions.

Several points are important here. First, a multimethod approach enables you to generate more in-depth, nuanced, or complex knowledge about phenomena. Consider the example in Chapter 1 in which the investigators used measurement to examine improvement in comprehension and then proceeded to investigate the “experience” of using the Web site through naturalistic methods. Second, although mixed method approaches are complex, as in all other forms of inquiry, they require purposeful and logical development that combine elements of the thinking and action processes from both the naturalistic and the experimental-type traditions for each essential in a research endeavor.

A third important point is that integrated studies transcend the classic philosophical and methodological paradigm debates and enhance scientific inquiry. Integration is based on the philosophical paradigm of pragmatism. As suggested first by Brewer and Hunter17 and more recently by Tashakkori and Teddlie,16 contemporary researchers who adopt integrated or mixed methods are not necessarily proceeding from mixed philosophical bases but from a single perspective, that of pragmatism. Briefly, pragmatism is a school of thought in which concepts such as “truth” and “reality” are relative and purposive. Given this philosophical paradigm, the purposive choice of methodology, including mixed methods, is most desirable.

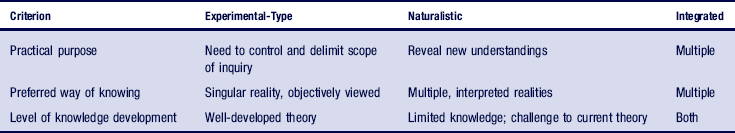

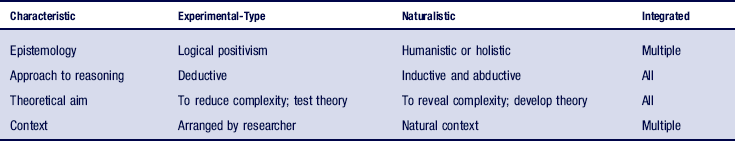

Table 3-1 summarizes the essential characteristics of experimental-type, naturalistic, and integrated inquiries. Examining the differences will help you understand the foundations of each tradition and its integration with the other.

TABLE 3-1

Four Distinguishing Characteristics of the Research Traditions Characteristics of the Research Traditions

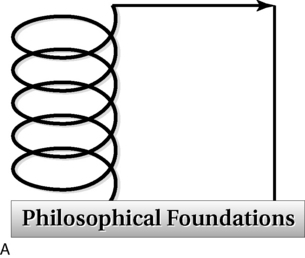

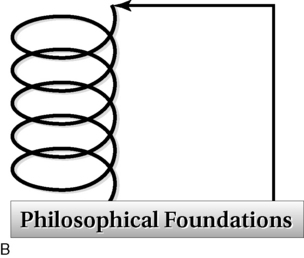

We suggest five distinct ways in which the research traditions can be integrated. Figure 3-1, A, shows a study design that initially involves a form of naturalistic inquiry, followed by an experimental-type approach. Usually in this strategy, the purpose of the naturalistic inquiry is to gain an understanding of the boundaries or dimensions of a particular construct or to generate a theory or set of propositions. If the purpose is to define a particular construct or concept, the investigator uses the naturalistic process to inform the development of an instrument or set of measures for use in a quantitative study. If the purpose is to generate or modify a theory using the naturalistic process, this study phase is followed by an experimental-type design, which formally tests an aspect of the theory that has been developed.

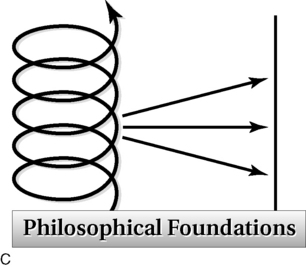

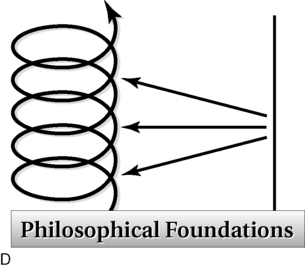

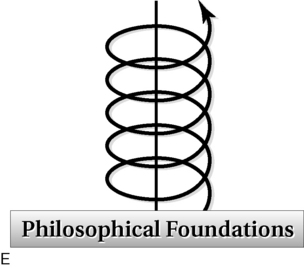

Figure 3-1 A, Design strategy that involves naturalistic inquiry followed by an experimental-type approach. B, Design strategy that begins with an experimental-type approach and then introduces naturalistic techniques. C, Design strategy in which integration occurs at several points in a naturalistic study. D, Design strategy in which integration occurs at several points in an experimental-type study. E, Design strategy in which integration occurs throughout all thinking and action processes.

Figure 3-1, B, presents a strategy for integrating the research traditions that involves the opposite sequence of A. In this integration scheme, the investigator begins with an experimental-type approach and then introduces naturalistic techniques. Usually in this approach, the quantitative findings suggest the need for more in-depth and complex exploration of a particular phenomenon. In Figure 3-1, C, integration occurs at several points throughout the research process. As a naturalistic study unfolds, elements of emerging theory are tested with experimental-type strategies. Similarly, Figure 3-1, D, depicts an integrated design in which experimental-type inquiry reveals the need to develop insights using naturalistic techniques.

In their work on the meaning and value of wheeled mobility for persons with mobility impairments, Hoenig, Giacobbi, and Levy18 suggested mixed methods as one of the most comprehensive and useful ways to conduct research that will improve practice and use of devices. Finally, Figure 3-1, E, depicts the most fully integrated design. In this scheme, the investigator integrates a study from the beginning and throughout all thinking and action processes.

Selecting a research tradition and design strategy

How does one decide which tradition to work from and which particular design strategy to choose? The selection of a design strategy is based on three considerations: (1) what you want to accomplish, or your purpose in conducting the research; (2) the way in which you think or reason about phenomena; and (3) the level of knowledge development in the area to be investigated.

Purpose of Research

Research is a purposeful or “intentional goal directed” activity. That is, research is conducted for a specific reason—to answer a specific question or query or to solve a particular controversy or issue. This point is central to the way in which we present the world of research to you throughout this book. The view of research as purposeful is shared by other scientists as well.16

Think about what we mean here by “purpose.” Purpose drives the decision to engage in research. Assume that you work in a health setting in which you believe the various practices and intervention approaches that you and your colleagues carry out are important and clinically effective in producing a desired outcome. Your administrator is not convinced, however, and costs associated with your practices are beginning to be questioned. You may need to conduct a research project to validate what you are doing and demonstrate the efficacy of the specific treatment approaches that you use. Alternatively, you may need to conduct a research study to help you systematically determine which elements of a new therapeutic approach are most effective in producing the desired outcome or whether the approach is being used with a population for which it was not previously tested. Similarly, assume that you are unsure as to the service needs of a particular group and that you need to obtain a better understanding to develop programming for this group.

Consider also the following specific examples of how purpose drives the selection of a design:

As you can see, purpose is a powerful force that drives the selection of a research strategy. In the first example, the administrator selected a strategy that she, as the researcher, could control and one that was based on the a priori assumptions she was willing to make. In the second example, the administrator selected a strategy that would uncover information that had not been previously determined. Because patient needs, as perceived by patients and families, were shaping institutional programming, an inductive, naturalistic design strategy was selected.

It is not uncommon to have more than one purpose for your study. Consider the example in Chapter 1. In that example, disparities in access to Web-based heath information was already known. However, the investigators had a hunch that literacy and visual access were major issues. So they used experimental-type measurement to verify this hunch and test the comprehension outcomes of their intervention. However, without conducting naturalistic inquiry, they could not have met their purpose of understanding user preference and experience in using the Web site. To meet these goals, they therefore chose naturalistic methods.

Preference for Knowing

Your preferred way of knowing is a second important consideration when selecting a particular category of research design. Selecting a design strategy is based in part on your implicit philosophical view, your espousal of the existence and nature of “reality” (ontology), your view of “if we can know” and if so “how we know what we know” (epistemology), and your comfort level with epistemological assumptions. Typically, we do not consciously reflect on our preferred way of knowing. It is usually demonstrated through which research approach makes the most sense to us and feels the most comfortable. Also, investigator personalities often influence the inclination to participate in one of the two traditions or in an integrated inquiry.

Level of Knowledge Development

The third consideration in selecting a research design involves the level of knowledge that has been developed in the particular area of interest. When little or nothing is understood about a phenomenon, a more descriptive and naturalistic approach to inquiry is indicated. When a well-developed body of knowledge has been advanced, predicting designs may be more appropriate and may suit the purposes of the investigator. However, this is not to suggest that naturalistic inquiry is chosen only when little knowledge has been developed. It may be possible that even with a well-developed body of knowledge, phenomena are not explained to the researcher's satisfaction. In this case, one might choose a naturalistic approach to unveil new insights that have not been elucidated through well-tested theory. Again, choice is based on a combination of the level of knowledge and the investigator's purpose. We explore the relationship of knowledge to design selection in more detail in subsequent chapters.

Table 3-2 summarizes the criteria for selecting designs across the research traditions.

Summary

We have made the following six major points in this chapter:

1. Experimental-type research is based in a single epistemological framework of logical positivism and involves primarily a deductive process of human reasoning.

2. Naturalistic inquiry is based in multiple philosophical traditions that can be categorized as pluralistic and holistic in their perspectives and involves inductive and abductive processes of human reasoning.

3. Integrated research, which is based on its own philosophical foundation of pragmatism, draws on strategies from both experimental-type and naturalistic inquiry traditions, and may involve multiple and varied thinking and action processes.

4. Each tradition has a distinct language and flow of thinking and action procedures.

5. Mixing methods requires a sound grasp of the thinking and action practices in each of the two primary traditions.

6. The selection of a strategy is based on your preferred way of knowing, your research purpose, and the level of knowledge development in the area of interest.

References

1. Hume, D. A treatise on human nature: being an attempt to introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral. London: Longrans, Green, & Co, 1974.

2. Russell, B. Introduction to mathematical philosophy. New York: Macmillan, 1919.

3. Hoover, K.R. The elements of social scientific thinking, ed 2. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1980.

4. Cook, T.D., Campbell, D.T. Quasi-experimentation: design and analysis issues for field settings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979.

5. Babbie, E. The practice of social research, ed 12. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth, 2009.

6. Campbell, D.T., Stanley, J.C. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963.

7. Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y. Landscape of qualitative research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 2007.

8. Husserl, E. Ideas: general introduction to pure phenomenology. New York: Macmillan, 1931. [(Boyce WR, translator)].

9. Denzin, N. Interpretive interactionism. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2001.

10. Randall, J.H., Buchler, J. Philosophy: an introduction. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1962.

11. Denzin, N. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2008.

12. Reason, P., Rowan, J. Human inquiry. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1981.

13. Silverman, M. Facing post-modernity: contemporary French thought on culture and society. New York: Routledge, 1999.

14. Anastas, J.W., McDonald, M.L. Research design for social work and the human services. New York: Lexington Books, 1994.

15. Padgett, D. Qualitative methods in social work research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2007.

16. Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C. Foundations of mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2009.

17. Brewer, J., Hunter, A. Foundations of Multimethod Research: Synthesizing Styles. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 2006. [p 4].

18. Hoenig, H., Giacobbi, P., Levy, C. Methodological challenges confronting researchers of wheeled mobility aids and other assistive technologies. Disabil Rehabil Assistive Technol. 2007;2:159–168.

Consider a case in which an administrator of a rehabilitation unit in a large teaching and research hospital has just been informed that her inpatient rehabilitation unit may be closed if she cannot demonstrate the value of the department's programs. The administrator decides that she will implement a research project to demonstrate the value of the service to the patients who are being discharged. From the contemporary literature, she selects three criteria for measurement to define valuable intervention: (1) patient satisfaction, (2) rehabilitation staff time spent with each patient's family in preparation for discharge, and (3) level of daily living skill performance in the occupational therapy clinic before discharge. She selects and measures these three criteria deductively, because she knows that these strengths can be clearly demonstrated by her unit staff. Her purpose in conducting the research is to demonstrate the value of her unit so that it may continue to provide valuable services to patients. She selects a deductive strategy based on her previous knowledge of the strengths of her programs and the types of positive outcomes she hopes to achieve.

Consider a case in which an administrator of a rehabilitation unit in a large teaching and research hospital has just been informed that her inpatient rehabilitation unit may be closed if she cannot demonstrate the value of the department's programs. The administrator decides that she will implement a research project to demonstrate the value of the service to the patients who are being discharged. From the contemporary literature, she selects three criteria for measurement to define valuable intervention: (1) patient satisfaction, (2) rehabilitation staff time spent with each patient's family in preparation for discharge, and (3) level of daily living skill performance in the occupational therapy clinic before discharge. She selects and measures these three criteria deductively, because she knows that these strengths can be clearly demonstrated by her unit staff. Her purpose in conducting the research is to demonstrate the value of her unit so that it may continue to provide valuable services to patients. She selects a deductive strategy based on her previous knowledge of the strengths of her programs and the types of positive outcomes she hopes to achieve.