Legal Considerations

There exist several legal theories by means of which plaintiffs may proceed against defendant health professionals.

For instance, contract law has provided a basis for suits in which a health professional is accused of guaranteeing a result related to treatment such as promising that administration of local anesthesia and any subsequent procedure will be pain free. When the result does not meet the plaintiff’s personal satisfaction, remedy may be sought in court. Because the contract in this example was based on the patient’s subjective opinion, the defendant doctor must prove that the patient never felt pain—an extremely difficult assignment. Plaintiff suits based in contract law against health providers are relatively rare.

Recent history has seen a disturbing and dramatic increase in the number of suits filed under criminal law theories by government prosecutors in areas such as alleged fraudulent activity on the part of the health care provider and for plaintiff morbidity or mortality. Historically, prosecutors criminally attacking health providers must be able to prove that a criminal mind (mens rea) exists and that society has been injured. The current trend is to rewrite the law to not require proof of mens rea (such as in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act or “Obamacare”) to negate any real analyses of intent. This change bodes ill for health professionals and others in that they now have the burden of proof that requires defendants to prove their innocence, rather than requiring prosecutors to prove guilt. This singularly significant change in criminal law is exacerbated by the fact that the forum for such controversies may be a regulatory agency, rather than a courtroom with its attendant Constitutional safeguards.

However, the legal theory covering most health professional lawsuit activity is that of the tort. A tort is a private civil wrong not dependent on a contract. The tort may or may not lead to further prosecution under criminal or other legal theories, such as trespass to the person. Classically, a viable suit in tort requires perfection of four essential elements: duty, a breach of that specific duty, proximate cause leading to damage, and damage related to the specific breach of duty. A health professional may successfully defend a suit in tort by proving that no duty existed, that no breach of duty occurred, that the health professional’s conduct was not the cause of damage, or that no damage exists. In addition, the elements must be logically linked. For instance, if a doctor negligently administers a drug that the patient is historically allergic to and the patient contemporaneously develops agoraphobia, the doctor would not be liable for the agoraphobia.

Duty

Briefly, the health professional owes a duty to the patient if the health professional’s conduct created a foreseeable risk to the patient. Generally, a duty is created when a patient and a health professional personally interact for health care purposes. Face-to-face interaction at the practitioner’s place of practice most likely would fulfill the requirement of a created duty; interaction over the telephone, Internet, etc., may not be as clear-cut regarding establishment of duty.

Breach of Duty

A breach of duty occurs when the health care professional fails to act as a reasonable health care provider, and this in medical or dental malpractice cases is proved to the jury by comparison of the defendant’s conduct with the reasonable conduct of a similarly situated health professional. Testimony for this aspect of a suit for malpractice is developed by expert witnesses. Exceptions to the rule requiring experts are cases in which damage results after no consent was given or obtained for an elective procedure, and cases in which the defendant’s conduct is obviously erroneous and speaks for itself (res ipsa loquitur), such as wrong-sided surgery. In addition, some complications are defined as malpractice per se by statute, such as unintentionally leaving a foreign body in a patient after a procedure.

Standard of Care

Experts testifying as to alleged breach of duty are arguing about standard of care issues. It is often mistakenly assumed that the standard of the practitioner’s community is the one by which he will be judged. Today, the community standard is the national standard. If specialists are reasonably accessible to the patient, the standard will be the national standard for specialists, whether or not the practitioner is a specialist. The standard of care may also be illustrated by the professional literature. Health care professionals are expected to be aware of current issues in the literature, such as previously unreported complications with local anesthetics. Often articles will proffer preventative suggestions and will review treatment options.

Simply because an accepted writing recommends conduct other than that which the health care provider used is not necessarily indicative of a breach of duty. For instance, specific drug use other than that recommended by the generic Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR) is commonplace and legally acceptable as long as the health care provider can articulate a reasonable purpose for his conduct. Part of this reasoning may likely include a benefit/risk analysis of various treatment options for a specific patient.

In addition, there is no single standard of care treatment plan for a given situation. Several viable treatment plans may exist and all may be within the standard of care, such as the option of choosing different local anesthetic formulations for a procedure.

Finally, ultimately, the standard of care may be determined by the jury itself after it weighs expert opinion, the professional literature, opinions of professional societies or boards, and so forth.

Proximate Cause

Proximate cause is the summation of actual cause and legal cause. Actual cause exists if a chain of events factually flows from the defendant’s conduct to the plaintiff’s injury. Legal cause is present if actual cause exists, and if the plaintiff’s attorney can prove that the harm sustained was foreseeable or was not highly extraordinary in hindsight.

Damage

Damage is the element of the cause of action that usually is most easy to identify because it is most often manifested physically. Simply because damage is present does not mean that malpractice has been committed, but damage must be present to fulfill all elements of the tort.

The nation has seen a dramatic rise not only in tort-based malpractice lawsuits over the past several years, but also in regulatory activity (Obamacare alone will result in the creation of at least 159 new regulatory agencies), both or which result in the predictable sequelae of increased costs and decreased access to doctors for patients. Trauma centers have closed, doctors are actively and passively (i.e., by limiting their practice or opting for early retirement) leaving lawsuit-friendly communities or states, and patient consumers now are starting to feel directly the loss of health professional availability and other consequences of a litigation system that has never been busier.

The administration of local anesthesia is a procedure that is not immune to the liability crisis. Although extremely safe, given estimates that more than 300,000,000 dental local anesthetic administration procedures are performed annually in the United States, at times the administration of local anesthesia will result in unintended damage to the patient. If the elements of duty, breach of duty, and proximate cause accompany that damage, malpractice may have been committed. However, complications most often occur with no fault on the part of the local anesthetic administrator. In these situations, most complications are still foreseeable, and because they are predictable, the reasonable practitioner needs to be aware of optimal immediate and long-term treatment for the complications of local anesthetic administration.

The purpose of this chapter is not to describe in great detail the prevention or treatment of various local anesthetic complications, but to simply mention foreseeable complications and comment on the standard of care with regard to appropriate prevention and treatment. Obviously, some complications are common and others are rare, and frequency is an issue that would be considered in legal evaluation of a case. In any case, the health professional who is administering potent local anesthetics by definition tells the public that it can trust in that professional while in his or her care. When pretreatment questions arise, it is the health professional’s duty to investigate controversial or unknown areas to minimize risk and maximize the benefits of his or her therapeutic decisions. When foreseen or unforeseen complications arise, the health professional must be able to act in a reasonable manner to address these untoward events.

Adequate legal response to a local anesthetic complication or emergency is often equivalent to adequate dental or medical response. However, when damage persists, plaintiff attorneys will argue that the dental or medical response was not an adequate legal response and will seek damages. The fact that the treatment rendered by the practitioner may be recognized by most of the profession as optimal may not convince a jury when the plaintiff can find an expert who offers an opposite opinion. However, damage alone will not prove malpractice. The tort can be successfully defended by showing no duty, no breach of duty, or no proximate cause. In many cases, no matter what the complication discussed in this chapter, these legal defenses are the same in theory and are applicable across the board, although the dental/medical responses are more specific to the specific situation.

If one is uncomfortable with any of the various situations mentioned in this chapter, further individual research in that area may be warranted.

In addition to the civil, or tort, remedies available to the plaintiff patient, a health care practitioner may have to defend conduct in other forums. Depending on the disposition of the plaintiff and his or her representative, the conduct of the health practitioner may be predictably evaluated not only civilly, but perhaps criminally, or via other governmental agencies such as licensing boards, better business bureaus, and so forth. Although theoretically, the arguments presented by competing sides in these varying forums are the same no matter what the forum, very real differences are involved. In particular, the penalties and the burden of proof are significantly different.

If the case is taken to a state agency, typically the board that issued the health professional’s license, the rules of evidence are not onerous as far as admission by the plaintiff. Essentially, the regulatory agency can accept any evidence it deems relevant, including hearsay, which means the defendant may not have the right of facing an accuser. The burden of proof, which typically rests with the moving party or plaintiff, may even be arbitrarily assigned to the defendant by the agency. The reason why the rules of evidence are so liberal in state agency forums is because the issuance of an agency professional license may be deemed a privilege and not a right. The significance of proper representation and preparation if one is called before a regulatory agency cannot be understated when one considers the very real possibility of loss of a license and subsequent loss of ability to practice.

If one is summoned to a civil forum, the rules of evidence and the burden of proof are more strictly defined. Rules of evidence are subject to state and federal guidelines, although this is an area that is not black and white, and attorneys frequently are required to argue zealously for or against admission of evidence. In a civil forum, the burden of proof generally remains with the plaintiff, and the plaintiff is required to prove his or her allegations by a preponderance of evidence. Expressed mathematically, a preponderance is anything over 50%. This essentially means that anything that even slightly tips the scales in favor of the plaintiff in the jury’s opinion signifies that the plaintiff has met the burden and thus may prevail.

In criminal cases, which again may be initiated for exactly the same conduct that may place the defendant in other forums, the burden of proof rests squarely with the prosecution (i.e., the state or federal government). In addition, the burden is met only by proof that is beyond a reasonable doubt, not simply a preponderance of evidence. Although the definition of reasonable doubt is open to argument, reasonable doubt is a more difficult standard to meet than is found in agency or civil forums.

Consent

The consent process is an essential part of patient treatment for health care professionals. Essentially, consent involves explaining to the patient the advantages and disadvantages of differing treatment options, including the benefits and risks of no treatment at all. Often treatment planning will result in several viable options that may be recommended by the doctor. The patient makes an informed decision as to which option is most preferable to that patient, and treatment can begin.

Consent is essential because many of the procedures that doctors perform would be considered illegal in other settings, for instance, an incision developed by a doctor during surgery versus an equivalent traumatic wound placed in a criminal battery.

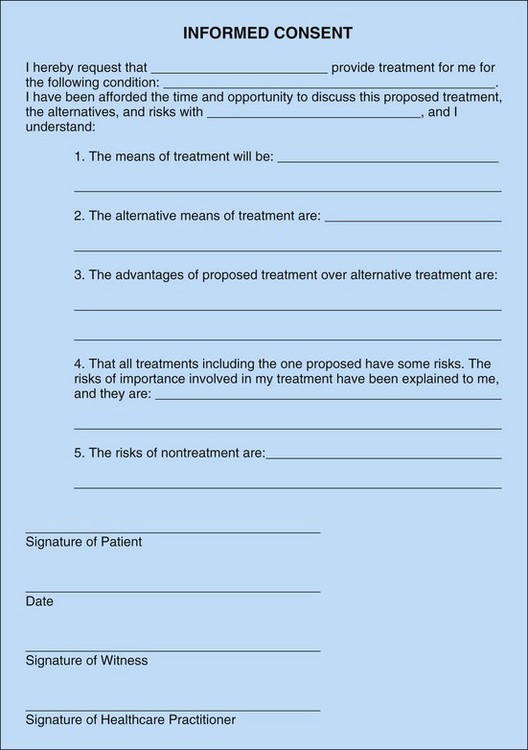

Consent may be verbal or written, but when a controversy presents at a later date, a written consent is extremely beneficial (Fig. 19-1). In fact, because many times consent is required to fulfill the standard of care for a procedure, lack of written consent may reduce the fact finding to a “he said/she said” scenario. This circumstance may greatly diminish the plaintiff’s burden of proving the allegations and may even shift the burden of proof to the defendant.

When the mentally challenged or children younger than the age of majority are treated, consent from a legal guardian is necessary for elective procedures. Whenever restraint is planned or anticipated, consent is warranted.

Consent obtained before one procedure is performed may not be assumed for the same procedure at a different time, or for a different procedure at the same time. In addition, consent obtained for one health care provider to treat may not be transferable to another health care provider, such as a partner doctor or an employee dental hygienist or registered nurse.

Consent is not necessary at times. When a patient is treated in an emergency setting (e.g., a spontaneously or traumatically unconscious patient), consent is implied. However, when possible, consent may be obtained from a legal guardian. The possibility of obtaining consent from a guardian before an emergency procedure is performed is time dependent. In an urgent situation, time may be available to discuss treatment options with a guardian. However, during a more emergent situation, taking time to discuss treatment options may actually compromise the patient.

Generally, emergency aid rendered in nondental or nonmedical settings does not require consent secondary to Good Samaritan statutes, which apply to “rescues.” However, a source of liability even when one is being a Good Samaritan is reckless conduct. Reckless conduct in a rescue situation often involves leaving the victim in a situation that is worse than when the rescuer found the victim. An example of such conduct is seen when a rescuer offers to transport a victim to a hospital for necessary treatment and then abandons the victim farther from a hospital than where the victim was initially found.

The patient who offers to sign a waiver to convince a practitioner to provide treatment, for instance, will not likely be held to that waiver if malpractice is suspected and then is adjudicated to exist; it is a recognized principle that a patient may not consent to malpractice because such consent goes against public policy.

With regards to local anesthetic administration, is consent necessary?

Consent is required for any procedure that poses a foreseeable risk to the patient. If the administration of local anesthetic could foreseeably result in damage to the patient, consent should be considered.

Further, some patients prefer to not be given any local anesthesia, even for significant operative procedures, thus rendering the administration of local anesthesia for dentistry optional and not necessarily required. It cannot be assumed that local anesthesia is automatically part of most dental procedures. If a patient is forced to have a local anesthetic without consent, technically a battery has occurred.

At times, local anesthetic administration is all that is necessary for certain diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as differential diagnosis or treatment of atypical facial pain syndromes, thus establishing the administration of local anesthesia as both diagnostic and therapeutic in and of itself.

Finally, local anesthetic administration involves injecting or otherwise administering potent pharmaceutical agents. These agents or the means used to administer them may inadvertently damage a patient. Any health professional conduct that may reasonably be expected to predictably result in damage requires consent.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 was signed into law by former President Bill Clinton on August 21, 1996. Conclusive regulations were issued on August 17, 2000, to be instated by October 16, 2002. HIPAA requires that the transactions of all patient health care information be formatted in a standardized electronic style. In addition to protecting the privacy and security of patient information, HIPAA includes legislation on the formation of medical savings accounts, the authorization of a fraud and abuse control program, the easy transport of health insurance coverage, and the simplification of administrative terms and conditions.

HIPAA encompasses three primary areas, and its privacy requirements can be broken down into three types: privacy standards, patients’ rights, and administrative requirements.

Privacy Standards

A central concern of HIPAA is the careful use and disclosure of protected health information (PHI), which generally is electronically controlled health information that is able to be distinguished individually. PHI also refers to verbal communication, although the HIPAA Privacy Rule is not intended to hinder necessary verbal communication. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) does not require restructuring, such as soundproofing, architectural changes, and so forth, but some caution is necessary when health information is exchanged by conversation.

An Acknowledgment of Receipt Notice of Privacy Practices, which allows patient information to be used or divulged for treatment, payment, or health care operations (TPO), should be procured from each patient. A detailed and time-sensitive authorization also can be issued; this allows the dentist to release information in special circumstances other than TPOs. A written consent is also an option. Dentists can disclose PHI without acknowledgment, consent, or authorization in very special situations, for example, perceived child abuse, public health supervision, fraud investigation, or law enforcement with valid permission (e.g., a warrant). When divulging PHI, a dentist must try to disclose only the minimum necessary information, to help safeguard the patient’s information as much as possible.

Dental professionals must adhere to HIPAA standards because health care providers (as well as health care clearinghouses and health care plans) who convey electronically formatted health information via an outside billing service or merchant are considered covered entities. Covered entities may be dealt serious civil and criminal penalties for violation of HIPAA legislation. Failure to comply with HIPAA privacy requirements may result in civil penalties of up to $100 per offense with an annual maximum of $25,000 for repeated failure to comply with the same requirement. Criminal penalties resulting from illegal mishandling of private health information can range from $50,000 and/or 1 year in prison to $250,000 and/or 10 years in prison.

Patients’ Rights

HIPAA allows patients, authorized representatives, and parents of minors, as well as minors, to become more aware of the health information privacy to which they are entitled. These rights include, but are not limited to, the right to view and copy their health information, the right to dispute alleged breaches of policies and regulations, and the right to request alternative forms of communicating with their dentist. If any health information is released for any reason other than TPO, the patient is entitled to an account of the transaction. Therefore dentists must keep accurate records of such information and provide them when necessary.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule indicates that the parents of a minor have access to their child’s health information. This privilege may be overruled, for example, in cases in which child abuse is suspected, or when the parent consents to a term of confidentiality between the dentist and the minor. Parents’ rights to access their child’s PHI also may be restricted in situations in which a legal entity, such as a court, intervenes, and when the law does not require a parent’s consent. To obtain a full list of patients’ rights provided by HIPAA, a copy of the law should be acquired and well understood.

Administrative Requirements

Complying with HIPAA legislation may seem like a chore, but it does not need to be so. It is recommended that health care professionals become appropriately familiar with the law, organize the requirements into simpler tasks, begin compliance early, and document their progress in compliance. An important first step is to evaluate current information and practices of the dental office.

Dentists should write a privacy policy for their office—a document for their patients that details the office’s practices concerning PHI. The American Dental Association (ADA) HIPAA Privacy Kit includes forms that the dentist can use to customize his or her privacy policy. It is useful to try to understand the role of health care information for patients and the ways in which they deal with this information while visiting the dental office. Staff should be trained and familiar with the terms of HIPAA and the office’s privacy policy and related forms. HIPAA requires a designated privacy officer—a person in the practice who is responsible for applying the new policies in the office, fielding complaints, and making choices involving the minimum necessary requirements. Another person in the role of contact person will process complaints.

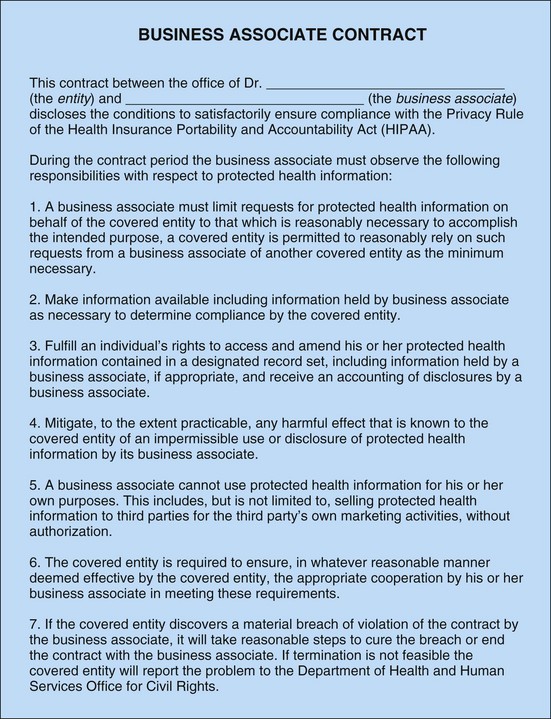

A Notice of Privacy Practices—a document that details the patient’s rights and the dental office’s obligations concerning PHI—also must be drawn up. Furthermore, any role of a third party with access to PHI must be clearly documented. This third party is known as a business associate (BA) and is defined as any entity who, on behalf of the health care provider, takes part in any activity that involves exposure of PHI. The HIPAA Privacy Kit provides a copy of the USDHHS “Business Associate Contract Terms”; this document provides a concrete format for detailing BA interactions (Fig. 19-2).

Figure 19-2 Sample business associate contract for compliance with the privacy rule of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

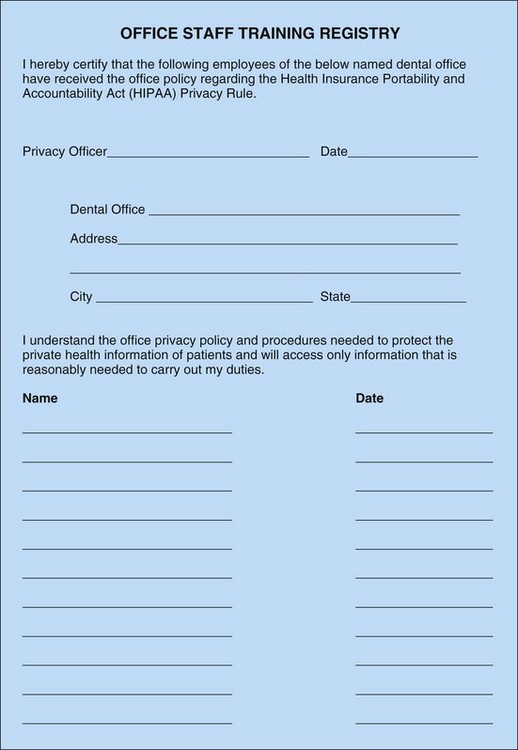

The main HIPAA privacy compliance date, including all staff training, was April 14, 2003, although many covered entities who submitted a request and a compliance plan by October 15, 2002, were granted 1-year extensions. Local branches of the ADA may be contacted for details. It is recommended that dentists prepare their offices ahead of time for all deadlines, including preparation of privacy policies and forms, business associate contracts, and employee training sessions (Fig. 19-3).

Figure 19-3 Sample staff training registry to be signed by all employees to verify receipt of the office policy to comply with the privacy rule of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

For a comprehensive discussion of all terms and requirements, a complete list of HIPAA policies and procedures, and a full collection of HIPAA privacy forms, the ADA should be contacted for an HIPAA Privacy Kit. The relevant ADA Website is www.ada.org/goto/hipaa. Other Websites that may contain useful information about HIPAA include the following:

• USDHHS Office of Civil Rights: www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa

• Work Group on Electronic Data Interchange: www.wedi.org/SNIP

• Phoenix Health: www.hipaadvisory.com

• USDHHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation: http://aspe.os.dhhs.gov/admnsimp/

Third Parties

When any untoward reaction occurs, including during local anesthetic administration, the complication will be treated more ideally by a responsive team trained to handle such events, rather than by the local anesthetic administrator alone.

Along with providing additional trained hands, third parties are witnesses and can testify to events leading up to, during, and after the event in question, and may prove invaluable in describing an event such as a psychogenic patient phenomenon.

Overdose

The term local anesthesia actually describes the desired effect of such a drug, not what actually occurs physiologically. Administration of a local anesthetic may or may not produce the desired depression of area nerve function, but it will definitely produce systemic effects. One must be prepared to articulate systemic considerations with regard to injection of these “local” agents.

Dosages of local anesthetic drugs administered to patients are most properly given and recorded in milligrams, not in milliliters, carpules, cartridges, cc’s, and so forth. The most standard limiting factor in the administration of certain doses of local anesthetics to a patient is the patient’s weight. Other factors that need to be considered include medical history, particularly cardiovascular disease, and previous demonstration of sensitivity to normal dosing. The presence of acute or chronic infection and concomitant administration of other oral, parenteral, or inhaled agents may alter the textbook recommendations for local anesthetic dosages. The reasonable practitioner needs to be able to readily determine the proper dosage levels to be administered to patients before the time of administration. At times, one local anesthetic formulation may be significantly more advantageous than another. The minimal amount of local anesthetic, and of vasoconstrictor contained therein if applicable, needed to achieve operative anesthesia should be used. An inability to properly dose most patients leads to provision of health care below the standard of care.

Overdose may occur without health professional error, as in a previously undiagnosed hypersensitive patient, or in a patient who gives an incomplete medical history. Intravascular injection can occur even with judicious negative aspiration through an appropriate needle and following slow injection and may result in overdose.

Generally, the initial presentation of overdose is physiologic excitement, which is followed by depression. Depending on the timing of the diagnosis of overdose, the treatment protocol will vary. Rapid accurate evaluation is very beneficial as opposed to a delayed diagnosis, and speaks favorably for the responsible health care provider. It is much more desirable to treat syncope secondary to overdose rather than cardiac arrest, which may follow inadequately treated syncope and respiratory arrest.

Adding to the diagnostic challenge is the fact that often more than one chemical is present within the local anesthetic solution that may cause overdose (e.g., lidocaine and epinephrine). The operator must be cognizant of the latency and duration of different components of the local anesthetic solution.

However, no matter the particular manifestation or whether fault is or is not included in the origin of any situation of overdose, the reasonable practitioner needs to be prepared to effectively handle the overdose. An inability to reasonably treat complications that are foreseeable, such as overdose, is a breach of duty.

If an overdose occurs, results can range from no damage whatsoever to death, and often depend on the preparedness of the health practitioner for this foreseeable emergency.

Allergy

Related to overdose, but not a dose-dependent manifestation of local anesthetic administration, allergic reactions are foreseeable, although relatively rare, particularly for severe allergic responses such as anaphylaxis.

An accurate medical history is mandatory in minimizing the occurrence of allergy. Patients, in part because doctors do not take the time to explain the difference between allergy, overdose, and sensitivity, often list any adverse drug reaction as an “allergy.” Inaccurate reporting of drug-related allergy by patients is not rare. In fact, more than half of patient-reported allergies are not allergies at all, but some other reaction that may not have even been drug related.

The duty of the health professional when administering local anesthetics includes avoiding known allergenic substances, including the local anesthetic in particular and any chemical additions to the local anesthetic solution. If an allergic reaction occurs, whether fault is present or not, the health care provider must be able to treat the drug-related allergy in a reasonable manner. Reasonable treatment may be the difference between resultant transient rhinorrhea versus death.

Instruments

A compromised syringe may still be usable in administering a local anesthetic. But if, for instance, the syringe cannot be controlled in a normal manner (e.g., secondary to an ill-fitting thumb ring), any damage resulting from such lack of control would be foreseeable and a breach of duty. A properly prepared and functioning syringe is mandatory for safe local anesthetic administration. Factors to be aware of in evaluating a syringe include all components of the syringe from the thumb ring, to the slide assembly, to the harpoon, to the threads that engage the needle, and so forth.

Local Anesthetic Cartridge

Originally, cartridges were much different than they are now. Problems that have been identified through the years include the fact that chemicals can leach from or into the solution within the cartridge, and that the contents are subject to extremes of heat or cold or prolonged shelf life. Cartridges are now coated with a protective film, thus helping to prevent any shattered glass effect from cartridge fracture, which can occur even with normal injection pressures.

Local Anesthetic Needle

Disposable needles have been the norm for decades; although they avoid many problems formerly manifest with reusable needles, malfunction can still occur. Needle breakage can occur with or without fault from the operator. Absent intentional bending and hubbing of the needle into loose mucosa, underlying muscle, and bone, needles still occasionally break for other reasons, as when a patient grabs the operator’s hand during an injection. Also, latent manufacturing defects will occasionally be noted during routine inspection of the needle before local anesthetic administration. In addition to needle barbs, the author has discarded preoperatively inspected needles with defects such as those seen in needles with patency in the needle shaft; needles that were partially or totally occluded; needles loose within the plastic hub; and needles with plastic hubs that did not effectively engage the metal threads of the syringe.

A needle-related complication is a plastic barb that is occasionally present when one separates the plastic casings of the needle preparatory to threading the needle hub onto the syringe. Such a barb may be present at the point where the heat sear secures the two casings together. Those who prepare the needle/syringe delivery system need to be aware of this barb not only when separating the casings, but also when recovering then needle after use.

Once again, broken needle instrument damage is foreseeable, as are other instrument failures. The prudent operator will be prepared to deal with this complication and will prevent further morbidity by means such as using a throat pack, not hubbing the needle, and having a prepared assistant who can pass a hemostat to the operator in a fashion that does not require the operator to take his eyes from the field. If a needle is lost in tissue, protocols have been established for retrieval of such foreign bodies, and if the operator is not comfortable with these procedures, an expeditious referral should be considered.

Contamination of the local anesthetic solution or delivery system (i.e., the needle) will likely produce complications, and thus should be assiduously avoided. It would be reasonable to expect a practitioner to be able to intelligently describe in some detail, if called upon to do so, the methods used to minimize any potential contamination. Limiting contamination has the added benefit of not compromising the health of the practitioner or any member of his team.

Any damage resulting from an unorthodox use of the syringe, needle, or cartridge may lead to open argument that a breach of the standard of care and thus breach of duty had occurred.

Alternative Delivery Systems/Techniques

At times practitioners may elect to use alternative delivery systems or techniques, such as periodontal ligament, intraosseous, or extraoral injections via specialized armamentaria. The standard of care, which includes the reasoning that a practitioner will, all things considered, choose the best treatment for his or her patient, certainly includes these alternate local anesthetic delivery systems or techniques.

As with any other routine or less than routine clinical treatment plan, the practitioner should be able to intelligently articulate reasoning for the decision. This is mandatory not only if a disgruntled patient seeks legal recourse, but also for nonlitigious patients who simply want to know why they have “never seen that before.”

Although promotional materials from a drug or equipment manufacturer may be helpful to the clinician in identifying advantages of new drugs or equipment, it is incumbent upon the health professional to make an independent and reasonable effort to identify potential disadvantages of new modalities.

Local Reactions to Local Anesthetic Administration

Topical or injected local anesthetics can cause reactions ranging from erythema to tissue sloughing in local areas secondary to several factors, including multiple needle penetrations, hydraulic pressure within the tissues, or a direct tissue reaction to the local anesthetic. Topical anesthetics in particular generally are more toxic to tissues than injected solutions, and dosages must be carefully administered. For instance, the practice of letting the patient self-administer prescription strength topical at home could certainly be criticized if an adverse reaction occurs.

Local tissue reactions may be immediate or delayed by hours or days; thus it is mandatory in this situation, as it is in others, for the patient to have access to a professional familiar with such issues, even during off hours. Simply letting patients fend for themselves or advising them to go to the emergency room may not be the best option in providing optimal care.

Finally, one should be able to reasonably justify the use of topical anesthetics for intraoral injection purposes because some authors have opined that these relatively toxic agents are not objectively effective.

Lip Chewing

Local tissue maceration secondary to lip chewing most often occurs in children status post an inferior alveolar nerve or other trigeminal nerve third division injection. Tissue maceration may also be seen in patients whose mental status has been compromised by sedatives, general anesthetics, central nervous system trauma, or during development. A prudent practitioner will advise any patient who may be prone to such an injury, and that patient’s guardian, to be aware of the complication. If this complication is not prevented, it must be properly treated when diagnosed.

Subcutaneous Emphysema

Emphysema or air embolism can occur when air is introduced into tissue spaces. This complication usually is seen after incisions have been made through skin or mucosa, but it can also occur via needle tracts, particularly when gas-propelled pressure sprays, pneumatic handpieces, and so forth, are used near the needle tract. The sequelae of air embolism usually are fairly benign, although disconcerting to the patient. An unrecognized and progressive embolism can be life threatening. When a progressive embolism is diagnosed, the practitioner will not be criticized for summoning paramedics and for accompanying the patient to the hospital.

Vascular Penetration

Even with the most careful technique, excessive bleeding can occur when vessels are partially torn by needles. The fact that aspirating syringes are used reveals that placing needles into soft tissues is indeed a blind procedure. At times, the goal of an injection is intravenous or intra-arterial injection. This is not typically the case with the use of local anesthetics for pain control, and a positive aspiration necessitates that additional measures be taken for a safe injection. The prepared health professional should be able to articulate exactly what the goal of administration of a local anesthetic is, and how that is technically accomplished. For instance, why was a particular anesthetic and needle chosen? What structures might be encountered by the needle during administration of a block? In addition, what measures are taken if a structure is inadvertently compromised by a needle? Even with optimal preparation, vascular compromise can result in tumescence, ecchymosis, or overt hemorrhage that may need to be addressed. These conditions can be magnified by bleeding dyscrasia. The medical history may reveal certain prescriptions that may alter bleeding time; this may indicate the need for preoperative hematologic consultation.

Neural Penetration

Just as a rich complex of vessels is present in the head and neck area, so it is with nerves. Neural anatomy can vary considerably from the norm, and penetration of a nerve by a needle can occur on rare occasions, even in the most careful and practiced hands. Permanent changes in neural function can result from a single needle-stick; although this complication does not necessarily imply a deviation from the standard of care, the practitioner must be prepared to treat the complication as optimally as possible.

Lingual nerve injury is an event that has been zealously contested in the courts in recent years. Typically, rare instances of loss or change in lingual nerve function have occurred during mandibular third molar surgery. Plaintiff experts readily opine that but for negligence (i.e., malpractice), this injury will not occur, period. In these experts’ opinions, lingual nerves are damaged only secondary to unintentional manipulation with a surgical blade, periosteal elevator, burr, and so forth, when the operator is working in an anatomic area that should have been avoided. In spite of the fact that defense experts routinely counter these plaintiff opinions, occasionally juries will rule for the plaintiff, and lingual nerve awards have exceeded $1,000,000.

Although lingual nerve injury occasionally occurs secondary to unintentional contact with surgical blades, periosteal elevators, burrs, and so forth, when an operator unintentionally directly encounters an unintended anatomic structure, it is more likely that the injury results secondary to other means. For instance, lingual nerve anatomy has been shown to be widely variant from the average position lingual to the lingual plate in the third molar area. Lingual nerve position has been shown to vary from within unattached mucosal tissue low on the lingual aspect of the lingual plate, to firmly adherent within lingual periosteum high on the lingual plate, to within soft tissues over the buccal cusps of impacted third molars.

Permanent lingual nerve injury also occurs in the absence of third molar surgery and secondary to needle penetration during inferior alveolar/lingual nerve blocks. Lingual nerve injury can result from pressure placed on the nerve during operative procedures (e.g., with lingual retractors).

A higher incidence of lingual nerve injury has been noted with certain local anesthetic solution formulations over others. The practitioner whose patient develops paresthesia after routine use of, for instance, 4% local anesthetic solution instead of 2% solution must be prepared to explain such decisions as why solutions that are twice as toxic as others and generally are equally effective may have been habitually used. Obviously, the suggestion here is that no treatment should be rote; rather, treatment should be planned on a patient-by-patient basis after a thoughtful risk/benefit analysis has been performed.

Finally, lingual nerve injury can occur when no health care professional treatment whatsoever is provided. Paresthesia can occur with mastication, and a presenting chief complaint of anesthesia can occur spontaneously. Both of these conditions may be rectified by dealing with the pathology associated with the change in function, such as by removing impacted third molars or freeing the lingual nerve from an injury-susceptible position within the periosteum.

However, no matter what the cause, the prudent operator will be prepared to address neural injury effectively when it occurs.

Chemical Nerve Injury

It is not surprising that potent chemicals such as local anesthetics occasionally will compromise nerve function to a greater degree than they are designed to do. Local anesthetics, after all, are specifically formulated in an effort to alter nerve function, albeit reversibly. Just as systemic toxicity varies from local anesthetic to local anesthetic, so limited nerve/local toxicity at times may alter nerve function in a way that is not typically seen. Deposition of local anesthetic solutions directly on a nerve trunk or too near a nerve trunk in a susceptible patient may result in long-term or permanent paresthesia. Local anesthetic toxicity generally increases as potency increases. In addition, nontargeted nerves in the head and neck may be affected by local anesthetic deposition, as when transient amaurosis occurs after maxillary or mandibular nerve block when the optic nerve is affected. One should not be particularly surprised at the various neural manifestations of these potent agents given that toxic overdose is actually a compromise of higher neural functions. Anyone who chooses to utilize agents designed to relieve pain directly on or near nerve tissue must be prepared for even the rare complications seen. Adequate treatment may range from reassuring a patient who has transient amaurosis to treating or referring for treatment a patient with permanent anesthesia resulting from an adverse chemical compromise of the nerve caused by the local anesthetic solution or other agents.

Local Anesthetic Drug Interactions

Use of other local or systemic agents certainly will predictably affect and alter the latency, effect, duration, and overall metabolism of local anesthetics. Modern polypharmacy only complicates the situation. However, the health care professional must be aware of specific well-known drug interactions, in addition to the pharmacology of common drug classes. Oral contraceptives, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, other cardiovascular prescriptions such as antihypertensives and anticoagulants, thyroid medications, antihistamines, antibiotics, anabolic steroids or corticosteroids, psychogenic medications, and various street drugs may be considered common to the routine dental population.

Drugs interact with various receptor sites; drug therapy is based on potentiation or inhibition of normal physiologic responses to stimuli. Ideally, with local anesthetic, no unwanted systemic reactions occur, and local nerve tissues are reversibly inhibited for a relatively brief time, after which the tissues regain full function. Concomitant use of other agents can change the usually predictable course of a local anesthetic and vice versa.

For instance, the commonly used β-blocker propranolol has been shown to create a chemically induced decrease in liver function, specifically, hepatic blood flow, which can decrease lidocaine metabolism by as much as 40%. Long-term alcohol use induces enzymes dramatically. Methemoglobinemia has been reported to result from use of topical local anesthetics and over-the-counter Anbesol©.

Therapeutic areas of special concern arise in patients who are obviously ill, who report significant medical history, who report significant drug use (whether prescribed, over-the-counter, or herbal), and who are at extremes of age. The incidence of adverse local anesthetic drug interaction increases with patients who report risk factors, particularly cardiovascular risk factors, as opposed to the general population. Before the time of treatment, clinicians should acquire the knowledge needed to optimally treat such patients with increased potential for adverse drug reactions.

Psychogenic Reactions

At times the practitioner may have to deal with psychogenic reactions that may be mild or can be severe. For instance, the initial manifestation of a toxic overdose, whether noted or not, is excitement. Excitement may also occur secondary to nothing other than stress resulting from a situation in which the patient is not comfortable. Excitement may be manifested, for instance, by controlled or uncontrolled agitation, disorientation, hallucination, or somnolence.

Such reactions may be potentiated by pharmaceuticals administered acutely by the health professional, or by authorized or unauthorized agents taken by the patient before an appointment. The incidence of such reactions is increased with increased utilization of pharmaceuticals, particularly those that may affect the central nervous system, such as local anesthetics. These reactions can occur in children, adolescents, adults, or the aged.

Psychogenic reactions are often frustrating to diagnose and treat. It may be difficult to determine whether the reaction is occurring secondary to an administered drug, including local anesthesia, or as the result of other causes.

Treatment may require restraint if the patient is in danger of inflicting harm upon himself or herself, as might be seen in an epileptic seizure. Fortunately, most of these reactions are short term (i.e., often lasting only moments). However, occasionally, they may occur regularly over long periods of time. Some, such as hysterical conversion manifest by unresponsiveness, may require hospitalization.

Although many practitioners may diagnose such an event, prudence requires that one be aware of the cause and treatment of such reactions. Even when psychogenic reactions are handled appropriately, patients may assume that the health care professional “did something wrong” and may seek the advice of an attorney.

Eroticism

A singularly troublesome psychogenic reaction to potent agents is observed in which the patient reacts with sexual affections that may or may not be recalled at a later time. Historically, such reactions were fairly common during administration of cocaine solutions. Generally speaking, these reactions appear to be rare and usually are of relatively short duration. However, as with other psychogenic or hysterical phenomena, rapid diagnosis and treatment is optimal.

Although concomitant use of agents such as nitrous oxide or administration of minor tranquilizers may be of general benefit during administration of local anesthesia, these and many other agents have been reported to produce erotic hallucinations or behaviors in patients so predisposed.

In the case of eroticism, the practitioner who has administered local or other agents without a neutral third party present when such reactions occur will have more difficulty exonerating conduct than the practitioner who had witnesses to the reaction. In addition, with regard to eroticism, it has historically been more optimal to have witnesses of the same sex as the patient.

Occasionally, a patient may request to speak with or be treated privately by the health practitioner. Absent unusual circumstances, such as treating a close relative, practitioners may want to consider avoidance of situations such as treating an emergency patient alone after hours, or even speaking to a patient behind closed doors.

Postprocedure Evaluation

Any time that potent agents are utilized, an evaluation of the patient is necessary. This evaluation consists of at least a preoperative assessment, continuous examination during treatment when the drugs utilized are at peak effect, and a postoperative appraisal.

Although most adverse reactions to local anesthetics occur rapidly, delayed sequelae are possible. Just as patients who have been administered agents by intravenous, inhalation, oral, or other routes are evaluated post procedure, so too should patients who have been administered local anesthetics. Any question about a less than optimal recovery from local anesthesia should be addressed before the patient is released from direct care.

For instance, it is widely accepted that patients may drive after administration of local anesthesia for dental purposes. Occasionally, a postprocedure concern that may arise secondary to local anesthesia and/or other procedures may dictate that a patient who was not accompanied may need to obtain assistance before leaving the place of treatment. Patients whose employment requires higher than normal mental or physical performance may be cautioned about the potential effects of local anesthetic administration. As an example, U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy pilots are restricted from flying for 24 hours status post local anesthetic administration.

Some practitioners routinely call each patient after release and several hours after treatment has been terminated to ensure that recovery is uneventful. Such calls are usually welcomed by patients as a sign that their health care provider is truly concerned about his or her welfare. Occasionally, the practitioner’s call may enable one to address a developing concern or an objective complication early on.

Respondeat Superior

Respondeat superior (“let the superior reply”), or vicarious liability, is the legal doctrine that holds an employer responsible for an employee’s conduct during the course of employment. The common law principle that all have a duty to conduct themselves so as to not harm another thus also applies to employees assigned tasks by an employer. Respondeat superior is justified in part by the assumption that the employer has the right to direct the actions of employees. For the health professional, responsibility may be shared by clerical staff, surgical or other assistants, dental hygienists, laboratory technicians, and so forth. At times vicarious liability will be applied between employer doctors and employee doctors if the employee doctors are agents of the employer doctor within a practice.

Respondeat superior does not relieve the employee of responsibility for employee conduct; it simply enables a plaintiff to litigate against the employer.

An employer is not responsible for employee conduct that is not related to employment. What type of employee conduct is related to the job is an arguable proposition, as are most legal issues. For instance, the question of whether an employer is responsible for employee conduct outside the normal workplace is open to a case-by-case evaluation. Conduct during trips to and from the workplace may or may not be related to employment. For example, an employer probably would not be responsible for employee conduct when the employee is driving home from the place of employment. However, if the employer asked the employee to perform a task on the way home, responsibility for that employee conduct may attach. An employer generally is not responsible for statute violation or criminal conduct by employees.

An employer may not be responsible for an independent contractor. One test used to evaluate the relationship between an employer and another is to discern whether the employer has the authority to direct how a task is done, as opposed to simply requesting that a task be completed. For instance, a dentist may request that a plumber make repairs, but likely will not direct how the repairs are to be accomplished, so the plumber would likely be independent. The same dentist will request that a dental hygienist perform hygiene duties, but the dentist may choose to instruct how the duties will be performed, thus rendering the hygienist less independent.

With regard to the administration of local anesthesia, dentists and dental hygienists routinely accomplish this task. Generally speaking, and subject ultimately to state statutes, although a dental hygienist may be an independent contractor according to many elemental definitions, the dental hygienist generally is not an independent contractor with regard to the provision of health care services. This includes the administration of local anesthetics. Thus, the employee dentist may be adjudicated responsible for any negligent conduct that causes damage to a patient during the course of hygiene treatment.

With regard to the degree of supervision, one must consult the state statutes. Often verbiage such as “direct” or “indirect” supervision is used, and understanding the definitions of these or other terms is paramount for both supervising and supervised health care providers.

Statute Violation

Violation of a state or federal statute usually leads to an assumption of negligence if statute-related damage to a patient occurs. In other words, the burden of proof now shifts to the defendant to prove that the statute violation was not such that it caused any damage claimed.

Two basic types of statutes exist: malum in se and malum prohibitum. Malum in se (bad in fact) statutes restrict behavior that in and of itself is recognized as harmful, such as driving while inebriated. Malum prohibitum (defined as bad) conduct in and of itself may not be criminal, reckless, wanton, etc., but is regulated simply to, for instance, promote social order. Driving at certain speeds is an example of a malum prohibitum statute. The difference between legally driving at 15 mph in a school zone and driving at 16 mph in a school zone is not the result of a criminal mind but is a social regulatory decision.

For instance, if one is speeding while driving, several sequelae may result when that statute violation is recognized. First, the speeder may simply be warned to stop speeding. Second, the speeder may be issued a citation and may have to appear in court, argue innocence, pay a fine if found guilty, attend traffic school, etc. Third, if the speeder’s conduct causes damage to others, additional civil or criminal sanctions may apply. Fourth, the situation may be compounded civilly or criminally if multiple statute violations are present, such as speeding and driving recklessly or driving while intoxicated.

Occasionally, statute violation is commendable. For instance, a driver may swerve to the “wrong” side of the centerline to avoid a child who suddenly runs into the street from between parked cars. At times, speeding may be considered a heroic act, such as when a driver is transporting a patient to a hospital during an emergency. However, even if the speeder has felt that he is contributing to the public welfare somehow, the statute violation is still subject to review.

For health professionals, for instance, administration of local anesthetic without a current health professional license or Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) certification is likely a violation of statute. If the type of harm sustained by the patient is the type that would have been prevented by obeying the statute, additional liability may attach to the defendant.

Conversely, an example of a beneficial statute violation occurred when a licensee did not fulfill mandatory basic CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) certification, but chose to complete ACLS (advanced cardiac life support) certification instead. When admonished by the state board that a violation of statute had occurred, potentially putting the public at greater risk, the licensee pointed out to the regulatory board that ACLS certification is actually more beneficial to the public than CPR. The licensing board then changed the statute to allow CPR or ACLS certification as a requirement to maintain a license.

Generally, employers are not responsible for statute violations of employees. An exception to this guideline is seen in the health professions. When employees engage in the practice of dentistry or medicine, even without the knowledge or approval of the employer, both that employee and the employer may be held liable for damage. Employer sanctions may be magnified, such as loss of one’s professional license, if an employee practices dentistry or medicine with employer knowledge.

Finally, at times some types of specific conduct are defined statutorily as malpractice per se. For instance, unintentionally leaving a foreign body in a patient after a procedure may be deemed malpractice per se. In these types of cases, theoretically simply the plaintiff’s demonstration of the foreign body, via radiograph, a secondary procedure to remove the foreign body, etc., may be all that is required to establish malpractice.

If Malpractice Exists

Although attorneys and doctors do not always agree on when all the elements of malpractice are present, occasionally the health professional may feel that he or she has made a mistake that has damaged a patient. As can be easily and successfully argued, simply the fact that a patient has damage, even significant damage, does not fulfill all requirements of the tort of malpractice.

If, however, the practitioner determines that a duty existed, the duty was breached, and breach was the proximate cause of damage, it is likely that malpractice has occurred. In this instance, the health professional is likely ethically, if not yet legally, responsible for making the patient “whole.” If the damage is minimal (e.g., transient ecchymoses), nominal recompense, perhaps even a judicious apology, may be all that is required. If, however, the damage is significant, significant recompense may be required.

Certainly, any significant damage whatsoever from malpractice requires that the health professional contact his liability carrier as soon as possible. The same holds true, even if damage is not evident, when the health care professional receives notice of patient dissatisfaction, often in the form of a request for records. The liability insurance carrier’s representative will help evaluate the situation and will provide valuable insight from a significant experience pool. In all likelihood, the carrier will be more successful in negotiating a settlement to any case that is controversial as far as damages. The practitioner should be very cautious about undertaking any such negotiations without his carrier’s input. Such unauthorized negotiations, or similar conduct, such as not informing the carrier about a potential complaint in a timely fashion, may even cause liability coverage to become the practitioner’s sole responsibility. At times, if the practitioner and the patient still have a good working relationship, the carrier will allow the practitioner to negotiate a reasonable settlement. This course of action is advantageous in that the patient receives immediate financial aid that may be necessary for additional expenses or time off from work. In addition, the plaintiff patient will not be required to overcome the assumption that the health care provider acted reasonably and to prove malpractice, which may be very difficult.

No matter whether the damage is secondary to negligence, the practitioner must try to treat the patient optimally. It is hoped that the patient will not independently seek treatment elsewhere because this course of action may simply prolong recovery and aggravate future legal considerations. One near universal finding in filed and served malpractice actions is criticism, usually unwarranted, by a nontreating health professional. If, on the other hand, referral would be beneficial, the practitioner should facilitate that referral for the patient and not just send the patient out to fend alone. After a referral is made, continued care as needed for the patient is advisable if possible.

Once legal action has been initiated, it may be wise to refuse further treatment for the patient because the patient has now effectively expressed the opinion that the practitioner’s conduct was below the level of the standard of care and has resulted in damage. It is an unfortunate circumstance when a plaintiff patient realizes that the perceived malpractice did not exist and is unable to continue care with the health professional most familiar with the intricacies of that patient’s individual circumstances.

Many patients shortsightedly and unintentionally limit their health care options by pursuing malpractice actions. Most malpractice cases take years to resolve and involve great expense for both the defendant and the plaintiff. Ultimately, a vast majority of alleged malpractice claims result in adjudication in favor of the defendant doctor. No matter who prevails in a malpractice claim, for both the defendant and the plaintiff the victory is often Pyrrhic when the temporal, social, and economic costs are factored in.

Conclusion

The administration of local anesthetics may undergo change with time secondary to new drugs, new instrumentation, and new knowledge bases. The law is even more subject to variation, often with each session of a legislative body or secondary to a significant court case. For instance, the philosophy of detailed versus general informed consent has undergone several permutations over the years. The decision of one court in a contractual, criminal, or civil tort proceeding may be appealed by the losing party and eventually reversed by another court secondary to a new fact pattern or simply as the result of re-evaluation of the same fact pattern under different legal formulae.

However, one thing that never changes is that reasonable and responsible health care practitioners will continue to be informed as to the current standard of care and will attempt to optimize their decision making and treatment planning for patients on an individual basis after a realistic risk versus benefit analysis. The opinions printed in this chapter and in this text are meant as guidelines and may be subject to modification on an individual patient treatment basis by knowledgeable practitioners and informed patients.

Arroliga, ME, Wagner, W, Bobek, MB, et al. A pilot study of penicillin skin testing in patients with a history of penicillin allergy admitted to a medical ICU. Chest. 2000;118:1106–1108.

Associated Press. Jury acquits Pasadena dentist of 60 child endangering charges. March. 5, 2002.

Bax, NDS, Tucker, GT, Lennard, MS, et al. The impairment of lignocaine clearance by propranolol: major contribution from enzyme inhibition. Br J Clin Pharm. 1985;19:597–603.

Burkhart, CG, Burkhart, KM, Burkhart, AK. The Physicians’ Desk Reference should not be held as a legal standard of medical care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:609–610.

Cohen, JS. Adverse drug effects, compliance, and initial doses of antihypertensive drugs recommended by the Joint National Committee vs the Physicians’ Desk Reference. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:880–885.

Cohen, JS. Dose discrepancies between the Physicians’ Desk Reference and the medical literature, and their possible role in the high incidence of dose-related adverse drug events. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:957–964.

College, C, Feigal, R, Wandera, A, et al. Bilateral versus unilateral mandibular block anesthesia in a pediatric population. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:453–457.

Covino, BG, Vassallo, HG. Local anesthetics mechanisms of action and clinical use. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1976.

Daublander, M, Muller, R, Lipp, MD. The incidence of complications associated with local anesthesia in dentistry. Anesth Prog. 1997;44:132–141.

Dyer, C. Junior doctor is cleared of manslaughter after feeding tube error. BMJ. 2003;325:414.

Evans, IL, Sayers, MS, Gibbons, AJ, et al. Can warfarin be continued during dental extraction? Results of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40:248–252.

Faria, MA. Vandals at the gates of medicine. Macon, Ga: Hacienda Publishing; 1994.

Fischer, G, Reithmuller, RH. Local anesthesia in dentistry, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1914.

Gill, CJ, Orr, DL. A double-blind crossover comparison of topical anesthetics. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;98:213–214.

Gilman, CS, Veser, FH, Randall, D. Methemoglobinemia from a topical oral anesthetic. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:1011–1013.

Goldenberg, AS. Transient diplopia as a result of block injections: mandibular and posterior superior alveolar. N Y State Dent J. 1997;63:29–31.

Kern, S. Saying I’m sorry may make you sorry. N V Dent Assoc J. Winter 2010–2011;12:18–19.

Lang, MS, Waite, PD. Bilateral lingual nerve injury after laryngoscopy for intubation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1497–1498.

Lee, TH. By the way, doctor…My hair has been thinning out for the past decade or so, but since my doctor started me on Lipitor (atorvastatin) a few months ago for high cholesterol, I swear it’s been falling out much faster. My doctor discounts the possibility, but I looked in the Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR) and alopecia is listed under “adverse reactions.” What do you think? Harv Health Lett. 2000;25:8.

Lustig, JP, Zusman, SP. Immediate complications of local anesthetic administered to 1,007 consecutive patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:496–499.

Lydiatt, DD. Litigation and the lingual nerve. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:197–199.

Malamed, SF. Handbook of local anesthesia, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 1997.

Malamed, SF, Gagnon, S, Leblanc, D. Efficacy of articaine: a new amide local anesthetic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:635–642.

Meechan, JG. Intra-oral topical anaesthetics: a review. J Dent. 2000;28:3–14.

Meechan, JG, Cole, B, Welbury, RR. The influence of two different dental local anaesthetic solutions on the haemodynamic responses of children undergoing restorative dentistry: a randomised, single-blind, split-mouth study. Br Dent J. 2001;190:502–504.

Meyer, FU. Complications of local dental anesthesia and anatomical causes. Anat Anz. 1999;181:105–106.

Moore, PA. Adverse drug interactions in dental practice: interactions associated with local anesthetics, sedatives, and anxiolytics. Part IV of a series. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:541–554.

Mullen, WH, Anderson, IB, Kim, SY, et al. Incorrect overdose management advice in the Physicians’ Desk Reference. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:255–261.

Olson, WK. The litigation explosion, what happened when America unleashed the lawsuit. New York: Penguin Books; 1991.

Orr, DL. Airway, airway, airway. N V Dent Assoc J. 2008;9:4–6.

Orr, DL. The broken needle: report of case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;107:603–604.

Orr, DL. Conversion part I. Pract Rev Oral Maxillofac Surg. 8(7), 1994. (audiocassette)

Orr, DL. Conversion part II. Pract Rev Oral Maxillofac Surg. 8(8), 1994. (audiocassette)

Orr, DL. Conversion phenomenon following general anesthesia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:817–819.

Orr, DL. Intraseptal anesthesia. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 1987;8:312.

Orr, DL. Is there a duty to rescue? N V Dent Assoc J. 2010;12:14–15.

Orr, DL. It’s not Novocain, it’s not an allergy, and it’s not an emergency!. N V Dent Assoc J. 2009;11:3.

Orr, DL. Medical malpractice. Pract Rev Oral Maxillofac Surg. 3(4), 1988. (audiocassette)

Orr, DL. Paresthesia of the second division of the trigeminal nerve secondary to endodontic manipulation with N2. J Headache. 1987;27:21–22.

Orr, DL. Paresthesia of the trigeminal nerve secondary to endodontic manipulation with N2. J Headache. 1985;25:334–336.

Orr, DL. PDL injections. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;114:578.

Orr, DL. Pericardial and subcutaneous air after maxillary surgery. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:921.

Orr, DL. A plea for collegiality. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1086–1092.

Orr, DL. Protection of the lingual nerve. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:158.

Orr, DL. Reduction of ketamine induced emergence phenomena. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:1.

Orr, DL. Responsibility for dental emergencies. N V Dent Assoc J. 2008;10:34.

Orr, DL, Curtis, W. Frequency of provision of informed consent for the administration of local anesthesia in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1568–1571.

Orr, DL, Park, JH. Another eye protection option. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:739–740.

Orr TM, Orr DL: Methemoglobinemia secondary to over the counter Anbesol, OOOOE. October 2010.

Penarrocha-Diago, M, Sanchis-Bielsa, JM. Opthalmologic complications after intraoral local anesthesia with articaine. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;90:21–24.

Pogrel, MA, Schmidt, BL, Sambajon, V, et al. Lingual nerve damage due to inferior alveolar nerve blocks: a possible explanation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:195–199.

Pogrel, MA, Thamby, S. Permanent nerve involvement resulting from inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:901–907.

Rawson, RD, Orr, DL, A scientific approach to pain control. 2000. University Press

Rawson, RD, Orr, DL. Vascular penetration following intraligamental injection. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:600–604.

Rosenberg, M, Orr, DL, Starley, E, et al. Student-to-student local anesthesia injections in dental education: moral, ethical, and legal issues. J Dent Educ. 2009;75:127–132.

Sawyer, RJ, von Schroeder, H. Temporary bilateral blindness after acute lidocaine toxicity. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:224–226.

Webber, B, Orlansky, H, Lipton, C, et al. Complications of an intra-arterial injection from an inferior alveolar nerve block. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1702–1704.

Wilkie, GJ. Temporary uniocular blindness and opthalmoplegia associated with a mandibular block injection: a case report. Aust Dent J. 2000;45:131–133.

Younessi, OJ, Punnia-Moorthy, A. Cardiovascular effects of bupivacaine and the role of this agent in preemptive dental analgesia. Anesth Prog. 1999;46:56–62.