Lower Extremity Orthotics

Deanna J. Fish, MS, CPO, Michael Lohman, MEd, OTR/L, CO, Dulcey G. Lima, OTR/L, CO and Karyn Kessler, OTR/L

1 Describe the general purposes and basic functions of lower extremity orthoses.

2 Understand normal gait and pathological gait.

3 Describe the biomechanical principles of lower extremity orthoses.

4 Describe the basic design principles of lower extremity orthoses.

5 Understand the relationship between structure (i.e., anatomic alignment) and function (i.e., walking ability).

6 Understand basic terminology used in lower extremity orthotic prescriptions.

7 Describe various components and materials commonly used in the fabrication of lower extremity orthoses.

8 Recognize commonly prescribed foot, ankle/foot, knee, knee/ankle/foot, hip, and hip/knee/ankle foot orthoses.

9 Outline the role of the occupational therapist in the orthotic treatment program.

10 Summarize short- and long-term orthotic treatment objectives.

11 Understand the importance of a multidisciplinary team approach.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

Historically, occupational therapy has primarily been involved in the provision of upper extremity orthotic services. However, with increased emphasis on the multidisciplinary team approach the scope of occupational therapy practice has expanded to include lower extremity orthotic care as it impacts the acquisition of occupational performance. It is important to delineate the role of occupational therapy in lower extremity, as opposed to upper extremity, orthotic treatment programs. In upper extremity orthotic practice, occupational therapists typically design, fabricate, fit, and supervise functional training. In effect, occupational therapists provide seamless delivery of orthotic services. Occupational therapists manage every stage of the upper extremity orthotic delivery process and are therefore able to adapt each step to individual needs and specific functional requirements.

In contrast, occupational therapists are not direct providers of lower extremity orthotic care. Typically, orthotists design, fabricate, and fit lower extremity orthotic devices and physical therapists provide functional gait training with lower extremity orthoses. Occupational therapy collaborates in the delivery of lower extremity orthotic services to ensure that the orthosis is designed to facilitate occupational performance at each stage of development.

Any given lower extremity device may address a biomechanical goal such as providing a stable base of support. The device may also address a functional gait training goal such as decreasing knee hyperextension during stance. However, if the orthosis does not also address the occupational performance goal (such as donning and doffing the device independently) the person may discard the orthosis. It is the occupational therapist’s role to anticipate such performance issues and initiate effective intervention before design and fabrication decisions have been completed. Occupational therapy clinicians are clearly the strongest advocate of advancing occupational performance goals.

Biomechanical and gait considerations are irrelevant when the lower extremity orthosis is rejected because it is too difficult to apply, interferes with activities of daily living, or is designed without consideration of individual strengths and weaknesses. With pediatrics, lower extremity orthoses can impact occupational performance differently and may be focused on the development of balance and equilibrium as a foundation for skill development and motor milestone acquisition. A lower extremity orthosis to position the hips may provide a stable base of support and help the child sit for longer periods of time to facilitate independent eating or writing skills. The same orthosis may not provide sufficient mobility for crawling and transitional movements unless it is designed to address these functional skills as well.

This chapter does not describe specific criteria used to design and fabricate orthoses, as do other chapters in this text. As the orthotist exclusively manages the fabrication process in lower extremity orthotics, it is not necessary or appropriate to cover this topic. However, if the occupational therapist is to be involved as part of the clinical team making decisions regarding lower extremity orthotics he or she must have a working knowledge of basic principles and terminology used by both physical therapists and orthotists in the decision-making process. This chapter is designed to provide a basic understanding and is not intended to be definitive or comprehensive in nature. Those with an interest in developing further expertise in this area should invest in additional educational seminars and reference texts.

Definition and Historical Perspective

An orthosis is generally identified as any orthopedic device that improves the function or structure of the body. Evidence of orthotic applications has been found as early as 2750 BCE [Bunch and Keagy 1976]. Excavation sites have uncovered mummies with various splints still intact. Historically, increased focus and advancements in orthotic design have centered on civil strife and periods of war. Today, continued advancements in the ever-expanding world of technology promote the development of new orthotic designs, materials, and components.

Purpose and Basic Function

The four basic functions of an orthosis include support and alignment, prevention or correction of deformity, substitution for or assistance of function, and reduction of pain. An orthosis is designed to address any one or all of these basic functions. Additional indications for lower extremity orthotic intervention are listed inBox 17-1.

General Applications

In the lower extremity, orthoses are prescribed for a variety of reasons and may be used on a temporary or permanent basis. For example, knee orthoses are often prescribed postoperatively to restrict joint motion while healing of soft-tissue structures occurs. After the rehabilitation phase, the knee orthoses are then either discontinued or used only during periods of increased physical activity.

In contrast, the young child with a diagnosis of spina bifida may require extensive orthotic designs to enable him or her to stand and walk. Such systems will be adjusted and replaced with growth but will play an ongoing role in maximizing and maintaining the child’s ambulation skills. In both instances, orthoses play a critical role in maintaining the structural integrity of the anatomy and the functional ability of the person. The relationship between structure and function is discussed in detail later in the chapter.

Basic Biomechanical Principles

Prescription criteria for lower limb orthoses are based on a thorough pre-orthotic evaluation of the person. Components of this evaluation process are listed inBox 17-2. Observational gait assessment (OGA) is performed with the person wearing shorts and a snug T-shirt. This allows the observer to relate the function of the lower limbs to the stability of the upper torso. Walking trials are performed with the person barefoot and then with any existing orthosis or ambulation aids being used. Biomechanics laboratories can offer a detailed analysis to assist in evaluation of the person’s gait deviations with the use of force plates and high-speed cameras. However, these facilities are sparse and the cost of such a procedure is often prohibitive. Individual goals, motivation, and available social support contribute to the success of any orthotic program.

Walking Requirements

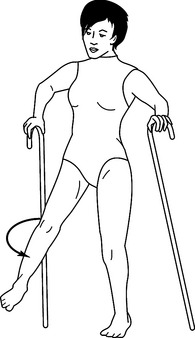

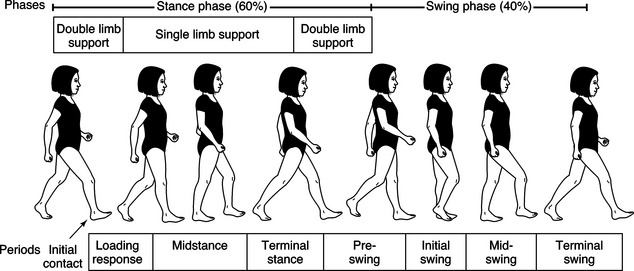

Walking is a complex series of muscular interactions that manipulate the skeletal structures in specific sequential and reciprocal patterns. As a result, normal walking occurs in a mechanically effective and energy-efficient manner (Figure 17-1). The gait cycle consists of heel-strike to ipsilateral heel-strike of the same limb, covering periods of double and single limb support as well as swing. The gait cycle can be further divided into eight specific phases: initial contact, loading response, mid-stance, terminal stance, pre-swing, initial swing, mid-swing, and terminal swing [Perry 1992]. Critical events occur at each phase of gait to enhance stability and encourage functional mobility. Extensive texts are available on this topic, which is not the focus of this chapter. Therefore, a brief summary is presented in the following as it relates to lower extremity orthotic treatment programs.

Figure 17-1 Gait cycle: normal gait. The normal gait cycle consists of swing and stance phases, with periods of double and single limb support.

Normal Gait

Limb stability is one of two basic components of walking. Each lower limb, in turn, must be effectively aligned and controlled to accept the transfer of body weight, support and balance the entire body mass independently, and then transfer the weight to the contralateral limb as it comes in contact with the ground. Sixty percent of the gait cycle is spent in periods of single and double limb support, when one and then both lower limbs support the body weight. Limb advancement is the second basic component serving to help translate the body mass forward and is dependent on the support provided by the contralateral stance limb. Swing phase accounts for 40% of the gait cycle. These actions occur reciprocally while maintaining forward momentum of the body through space with minimal metabolic costs.

Although most lower limb joint motions occur in the sagittal plane (i.e., hip and knee flexion and extension, ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion), motions also occur in the coronal and transverse planes. This serves to streamline the gait cycle and limit the translation of the center of mass (COM) to minimal vertical and horizontal excursions. As a result, a decrease in the displacement of the top-heavy trunk segment is evidenced and energy is conserved. The most efficient gait pattern for each individual occurs at a self-selected walking speed, when the person is trying neither to increase nor decrease normal walking speed.

Pathologic Gait

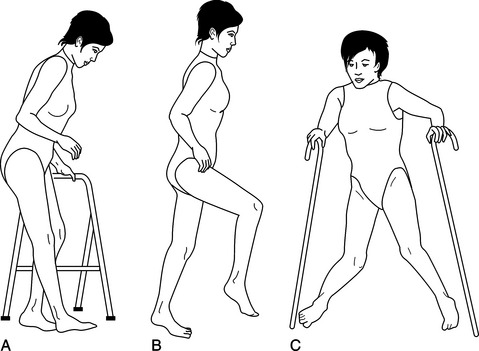

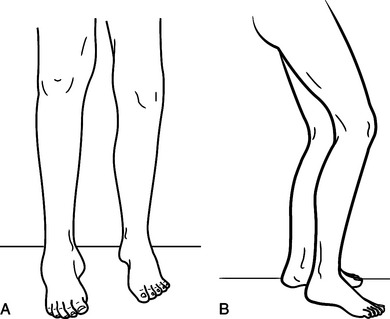

A pathologic gait pattern often develops secondary to neuromuscular deficits, joint instabilities, pain, disease processes, congenital involvements, and many other conditions (Figure 17-2). Excessive or insufficient joint motions occur and lead to exaggerated or inhibited movements of the body throughout the gait cycle. The normal walking speed of the individual will also be affected. Increases in energy costs tend to promote decreased walking speeds and further increases in energy costs.

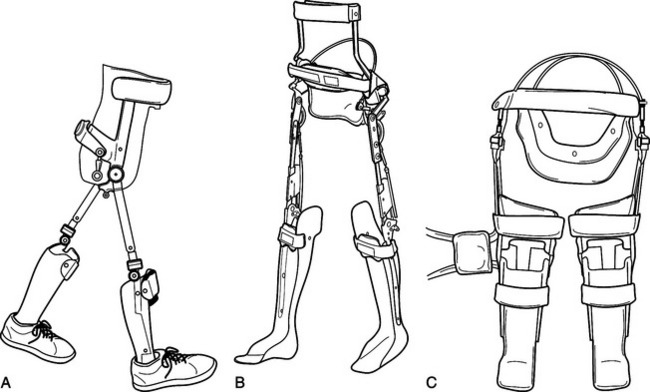

Figure 17-2 Pathological gait: various individual profiles: (A) anterior knee instability with forward trunk lean, (B) steppage gait with excessive hip and knee flexion to compensate for drop-foot, and (C) crouched gait.

Clinical training in observational gait assessment ensures the identification of all pathologic gait deviations in need of orthotic intervention. Commonly observed deviations include drop-foot, hyperextension or genu (knee) recurvatum, lateral trunk lean, anterior knee instability, genu varum or genu valgum, pelvic instability, increased lordosis, tone-induced equinovarus, pes planus, and so on. Observational gait assessment also evaluates many factors, such as overall symmetry, step lengths, loading patterns, width of the base of support, weight transfer, terminal stance stability, swing phase function, and trunk alignment, just to name a few. Other pathologic factors include joint contractures, muscle weakness, and disturbed motor control programs.

Functional Motions (Compensations)

Most persons acquire a pattern of walking that serves a functional rather than an efficient purpose, when compared with normal parameters. For example, when dorsiflexion capabilities at the ankle are lost, a person experiences a drop-foot condition. The toes drag on the ground during swing phase and contact first with the ground during the loading phase. Persons will adopt a gait pattern that provides ground clearance for the plantar-flexed foot during swing phase. This is accomplished by excessive hip and knee flexion (i.e., steppage gait) or by excessive hip circumduction (Figure 17-3). Both of these compensations achieve a functional result; specifically, ground clearance during swing phase. Although these compensations occur without conscious thought and may allow for ambulation, the need for an orthosis is supported by increased energy costs and safety concerns.

Dysfunctional Motions (Detractors)

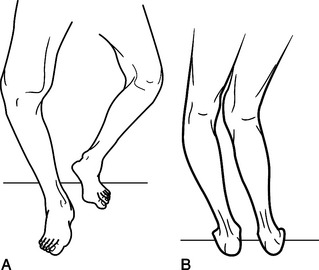

Although such clinically observable gait deviations detract from effective and efficient gait, some dysfunctional motions are more notably difficult to compensate for in a functional manner. Hyperextension (or “back knee”) is such a condition. This occurs as the knee moves in the posterior direction during mid-stance, often secondary to weakness of the quadriceps and/or posterior calf muscle groups. Without hyperextension, the person experiences uncontrolled knee flexion and collapse.

As a side note, a plantar-flexion contracture is often noted upon examination as either the primary cause or result of the posterior knee moment and serves to limit tibial advancement over the base of support during stance phase. Genu recurvatum (Figure 17-4) is the long-standing result of hyperextension, when permanent damage to the posterior soft-tissue structures of the knee has occurred. This gait disruption affects the efficiency of gait because the lower extremity is forced posteriorly as the body mass is attempting to move anteriorly over the limb. Working at odds, large truncal deviations are noted and energy costs increase dramatically.

Orthotic Design Principles

Principles of lower extremity orthotic design consider the interaction of anatomic and mechanical structures. The mid-tarsal, subtalar, talocrural, knee, and hip joints are evaluated in regard to the individual joint alignment and range of motion (ROM), as well as the interaction of these five major joints during the task of walking. Application of mechanical joints can serve to encourage, restrict, or eliminate potential joint motion.

Considerations of joint position, relief of pain, restriction of motion, or relief of weight bearing relate to the effect of the application of forces. Force is applied to effect an angular change at a specific joint in one or more of the three planes of motion. As a result, care is taken to apply forces over pressure-tolerant areas (i.e., soft tissue or adequate surface areas), with relief of force over pressure-sensitive areas (i.e., bony prominences). Mechanical leverage is another important concept, as specific force is increased with shorter lever arms and decreased with longer lever arms. Properly applied forces over adequate surface area with long lever arms exert less force for effective joint control than do orthotic designs with short mechanical lever arms.

Additional orthotic considerations include weight, cost, adjustability, ease of application, cosmesis (appearance), maintenance, and the necessary training required to ensure successful outcomes [Bunch et al. 1985, Kottke and Lehmann 1990]. These factors should be discussed thoroughly by the rehabilitation team and the individual before a final orthotic design is determined.

Relationship of Structure and Function

Structure and function are two important concepts to keep in mind during the individual evaluation and orthotic design processes. Structure relates to stability by realigning or maintaining the skeletal structure in a mechanically effective position through the application of externally applied forces. Function relates to mobility with controlled motion at anatomic joint structures. Both concepts have unique requirements and yet are extremely interdependent. Structural stability can eliminate function, just as altered function can lead to deterioration of joint structures. Compromises based on unique personal attributes are identified and addressed by the rehabilitation team.

Joint Alignment

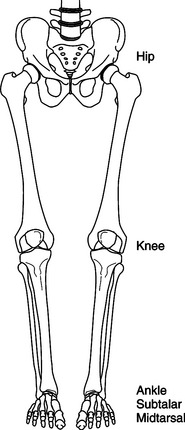

All five major joints (mid-tarsal, subtalar, talocrural, knee, and hip) of the lower extremities exhibit triplanar joint motion (Figure 17-5). Still, they work together during walking to allow progression of the body in the desired direction. These motions occur largely through the sagittal plane, specifically hip and knee flexion with ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. Alignment of skeletal joint levers is a critical component of efficient and effective ambulation.

Figure 17-5 Five major joints of the lower extremity. The hip, knee, ankle, subtalar, and mid-tarsal joints work in unison to produce a streamlined and energy-efficient gait.

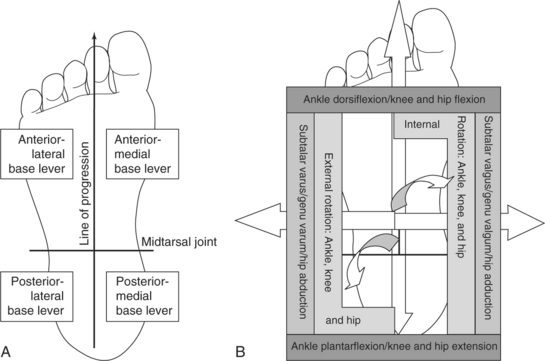

Mechanically speaking, the foot can be divided into anterior and posterior portions, with the mid-tarsal joint serving as the connection (Figure 17-6). Through mechanical leverage, the long anterior lever is used to control ankle dorsiflexion, knee flexion, and hip flexion. The short posterior lever limits ankle plantar flexion, knee extension, and hip extension. Medially, the first metatarsal ray and the medial heel act as medial levers to support proximal joint structures and prevent subtalar valgus and genu valgum, limit hip adduction, and discourage excessive internal rotation of the entire limb. The fifth metatarsal ray and the lateral heel serve as lateral levers to prevent subtalar varus and genu varum, limit hip abduction, and discourage excessive external rotation of the entire limb.

Figure 17-6 (A) The foot can be divided into anterior and posterior base levers, each with a medial and lateral component. (B) Anterior base levers resist dorsiflexion and flexion, posterior base levers resist plantar flexion and extension, medial base levers resist subtalar valgus and knee valgum, and lateral base levers resist subtalar varus and genu valgum. Anterior-medial base levers resist internal rotation and posteriorlateral base levers resist external rotation.

Joint Stability

The base levers of the foot are similar in concept to the foundation of a house. A square and true foundation always provides the best support. An unstable base of support has the potential to create larger moments of instability at proximal joint structures. For example, a pronated (flat) foot has clinically observable features: hind-foot valgus, mid-foot collapse, and forefoot abduction. Mechanical assessment reveals a loss of the anterior-medial forefoot and posterior-medial hind-foot base levers. Therefore, the ankle joint is subjected to excessive dorsiflexion, internal rotation, and medial displacement; the knee is subjected to flexion, internal rotation, and valgum moments; and the hip joint is subjected to flexion, internal rotation, and adduction moments. An effective orthotic design that returns joint stability and proper alignment to the mid-tarsal and subtalar joints will serve to effect positive alignment changes at the ankle, knee, and hip joints.

Three-point Force Systems

As mentioned earlier, the application of force is used to effect angular changes at deviated joints. A three-point force system (Figure 17-7) effects an alignment change with two forces working in opposition to a counterforce (or fulcrum). The counterforce is positioned on the convex side of the joint deviation, close to the joint requiring an angular change. The opposite two forces are positioned proximal and distal to the counterforce, on the side of the joint concavity. The greater the linear distance between opposing forces the less pressure is required to maintain the angular correction.

Components and Materials

A wide variety of mechanical joints and materials are now used in orthotic designs. Mechanical joints are designed to mimic anatomic joint function, and care is taken to approximate anatomic joint alignments. Orthotic joints are manufactured in a variety of metals and plastics, with unique design features to control available ROM. Special strapping is often used to enhance alignment and control. Material selection is based on the desired design characteristics of the orthosis. Material properties range from extremely flexible to extremely rigid. Different types of foam padding are available in variable thickness, density, and durability to meet different mechanical design requirements. Keep in mind that an orthosis is a mechanical device that requires periodic checkup and maintenance to ensure proper mechanical functioning and to extend the longevity of the orthosis.

There are a number of questions that need to be answered before selecting the appropriate material. Does the material need to be flexible or rigid? Lightweight or heavy duty? Inexpensive? Temporary or permanent? What is the length of time required for preparation? Can the materials be easily cleaned? Can the material be maintained easily? Can the material allow for easy donning and doffing? Although all concerns are usually not met at the first orthotic fitting, much frustration on the part of the team and the client can be avoided if all are involved early in the process and share the same end-product outcome goals.

Material selection is based on the desired design characteristics of the orthosis. Material properties range from flexible to rigid, lightweight to heavy-duty, inexpensive to costly, limited to prolonged durability, and minimal to extensive fabrication preparation. Each of these factors must meet the client’s anticipated activity level as well as demands of aesthetics, ease of cleaning, maintenance, and don/doff procedures. These various, at times conflicting, considerations compound the difficulty of clinical decision making in orthotic selection. Appropriate choices lead to acceptance and independence, whereas unwise selection may cause not only rejection of a device but unintended injury to the client.

The process of material selection weighs each of these factors in consideration of the client outcome or goal. The selection process can be relatively apparent. If the desired outcome is to gradually increase active motion of a postoperative knee joint over several weeks, the clinician selects an orthosis that is lightweight, inexpensive, adjustable, of limited durability, and easily fabricated. If, however, the desired outcome is to protect the same knee joint from ACL tear reoccurrence during a contact sport such as soccer the material selection process focuses on an orthosis that is highly durable, of rigid construction (probably involving extensive/costly fabrication), very low profile in design to minimize interference during the activity, easily cleanable to reduce skin irritation, and cosmetically appealing (as the orthosis would be highly visible).

More challenging material selection processes involve competition between factors. The client may desire a lightweight, flexible, inexpensive, easily fabricated device to reduce foot drop. These material selections, however, will not address the underlying problems of a severe osteoarthritic ankle, which may necessitate selections the client finds unacceptable. At times, material selection focuses on a single factor that supercedes all other considerations. To reduce hypertrophic scarring that accompanies severe burns, it is essential that a continuous hard smooth surface be applied 24/7 to achieve the clinical outcome of scar prevention/reduction.

All other factors of comfort, aesthetics, ease of don/doff procedures, fabrication procedures, and costs are subservient to the factor of material texture in the determination of the clinical outcome. For some conditions, hand function is severely limited. No matter how effective any knee/ankle/foot orthosis (KAFO) functions are in improving gait, if the client is unable to don/doff the device efficiently and consistently it will be rejected as not practical for their daily routine. It is imperative that therapists communicate their concerns during the material selection process, during the orthotic evaluation.

Orthotic Classifications

Three main types of orthoses are available. Prefabricated (or over-the-counter) designs are manufactured in a variety of sizes and offer immediate application, reduced cost, and simplicity. They are generally used as evaluative tools or for temporary use because the fit/function and the durability of these products are limited. Custom-fitted designs require a more involved measurement and fitting procedures to obtain better fit and function. Used for moderate involvements, custom-fitted designs are prescribed on both a temporary and definitive basis. Custom orthotic designs are the most sophisticated, requiring extensive measurements, castings, fitting, and follow-up procedures from a skilled orthotist. Most often prescribed on a permanent (or definitive) basis, a custom orthotic design is made to specifically fit the individual and is therefore more expensive to manufacture. The result, however, is a more intimately fitting device with greater joint control, limb stability, and improved function and mobility.

Another aspect to consider is whether a static or dynamic splint is warranted. The most common uses of static splints are (1) to support joints that need to be immobilized, (2) to help prevent further deformity, and (3) to prevent soft-tissue contractures. As an immobilizing force, these rigid devices place and maintain a joint or joints in one position while allowing healing of a fracture or an inflammatory condition. It is optimal to place and hold joints in a position of function. Static splints prevent further deformity by maintaining a controlled stretch on the affected joint.

Conversely, dynamic splints allow motion of a joint within a prescribed range while supporting other joints. Primary uses of dynamic splints include (1) to act as a substitute for lost motor function, (2) to correct a deformity, (3) to provide controlled motion, and (4) to facilitate fracture alignment and wound healing. The dynamic action comes from hinges or springs placed in line with the joint to be acted upon. The tension of the hinge/spring can be set at a prescribed ROM and tension can be based on the use and desired outcome. Dynamic splints are more complex in their design and fabrication than static splints. Understanding the functions and uses of the static and dynamic splint will lead to the most effective choice.

Orthotic Terminology

The terminology for lower extremity orthoses is based on the anatomic area affected by the orthosis. An arch support or shoe insert is called a foot orthosis (FO). An orthosis designed to address drop-foot is called an ankle/foot orthosis (AFO). The orthoses may be further defined by descriptive terms such as rigid FO or thermoplastic AFO, or may be designated by the function performed such as ground reaction AFO or stance-control KAFO. Consistency in terminology ensures effective communication within the rehabilitation team. Standard abbreviations for lower limb orthoses are listed inTable 17-1.

Duration of Use

Therapists and orthotists both make devices intended to support, align, stretch, control, and replace the function of compromised joints and muscle groups. Often the decision of whether the device is made by a therapist or orthotist is based on the amount of time the device is expected to be used. Splints that are usually made by therapists are fabricated from low-temperature splinting materials with a life span of 3 to 6 months. These splints can be technically demanding but the duration of time in the orthosis is limited. Low-temperature thermoplastic splinting materials do not require a scan or cast of the body part to be fabricated, and are contoured directly over the client’s skin or stockinette-covered skin.

Lower extremity splints, fabricated using components that are easily assembled, may also have metal attachments. They are assembled using hand tools normally available in the splinting lab. Splints used for smaller body parts such as the arms, hands, neck, and sometimes the lower leg can be changed fairly easily as the client moves through the rehabilitation process. Some rehabilitation centers use low-temperature materials to fabricate full body splints for postoperative positioning. However, working with large sheets of plastic that easily stick together is quite cumbersome and technically demanding.

Orthotists, on the other hand, use high-temperature thermoplastic material that is heated to 325° F or more. These devices (usually referred to as orthoses) are ordered when the orthosis is expected to be worn for more than 6 months or to withstand greater forces as in weight bearing. High-temperature thermoplastic material is too hot to be contoured directly over the client’s skin, and thus a scan or cast is taken of the affected body part to acquire a detailed mold. The mold is closed and filled with plaster. The high-temperature thermoplastic is then heated and draped over the mold under a vacuum to create the orthosis. After cooling, trim lines are drawn, and the plastic is removed using a cast cutter.

Edges are finished and buffed using grinders and routers, and any metal hinges or hardware are applied before the straps are attached. The high-temperature plastic and metal components are made to last for years, and can withstand the forces of spasticity and muscle weakness for longer periods of time than low-temperature splinting materials. A variety of high-temperature thermoplastic choices is available and these are chosen based on needed characteristics. Lower extremity orthoses have to withstand the repeated forces of weight bearing over long periods of time. Spinal orthoses are often made of more flexible high-temperature thermoplastic materials with full foam liners. Orthotic designs intended for high activity over long periods of time are best fabricated by an orthotist from high-temperature materials.

Foot Orthoses

A functional FO is designed to redistribute weight-bearing pressures over the plantar surface of the foot. Relief to painful areas, reduced stress to proximal joint structures, equalization of a limb length discrepancy, support to arches of the foot, and limiting motion at specific joints are some of the problems addressed by a foot orthosis [Goldberg and Hsu 1997]. Foot orthoses are available in prefabricated, custom-fitted, and custom designs, each yielding variable results relative to fit, function, comfort, sizing, cost, adjustability, personal acceptance/satisfaction, and effectiveness.

Biomechanical Function

Most FOs are biplanar designs, addressing joint deviations and providing support in the sagittal (i.e., mid-foot depression) and coronal planes (i.e., hind-foot and forefoot varus or valgus). More involved FO designs, such as the University of California Biomechanics Laboratory (UCBL) FO, offer triplanar support with additional control for transverse plane deviations (i.e., forefoot abduction or adduction). A thorough individual evaluation procedure is the basis for design and selection of the most appropriate FO.

General Indications and Contraindications

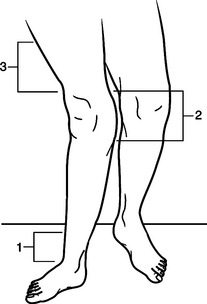

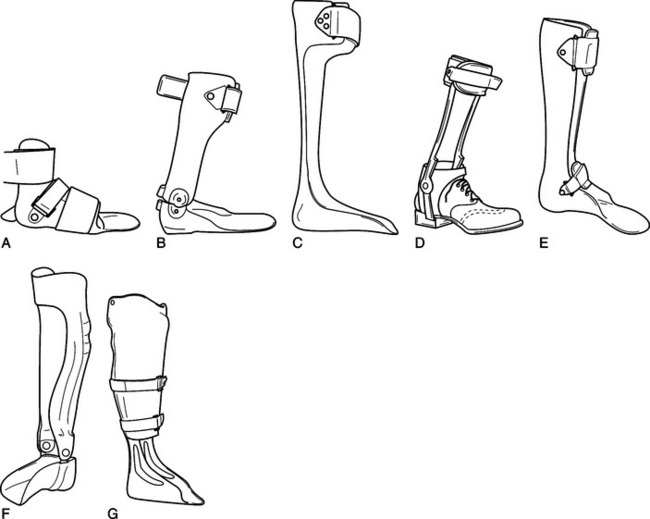

Prescription criteria for FOs are based on three main principles: accommodation, support, and correction. Accommodative FOs are generally fabricated of soft materials and are designed to provide additional padding, relief of pressure, and protection for insensate or deformed feet. Supportive orthoses are fabricated from semirigid materials, offering a greater degree of alignment control. Corrective orthoses tend to be manufactured from rigid materials and require extensive fitting procedures to obtain maximum joint alignment/correction and acceptance. A variety of orthotic designs are shown inFigure 17-8.

Design Options

FOs are measured in a variety of ways. Foam impressions, hand casting, or computerized mapping of the foot are the first steps in obtaining an accurate impression of the person’s foot. Material selection offers the greatest variety of design options. Open- and closed-cell foams, leather, cork, plastics, laminates, and other materials serve to create a flexible, semirigid, or rigid orthotic design. Joint alignment is altered via posting, where additional material is placed in a particular area of the plantar surface of the orthosis to limit ROM or to “tilt” the foot into the correct alignment. Maximum joint alignment is achieved in designs offering triplanar control.

Specific Applications

Pronated conditions are effectively treated with custom orthotic designs. Runners often experience an excessive and sustained pronation moment, which may involve excessive joint ROM or sustained pronation throughout the stance phase. An FO is helpful in reducing the hind-foot valgus deviation, depression of the longitudinal arch, and excessive forefoot flexibility and supination. A semirigid orthosis allows a normal pronation moment to occur from heel-strike through the loading response, and then encourages the foot to become rigid for improved forward progression and propulsion.

Diabetic and insensate feet require daily inspection to prevent pressure sores and ulcerations from the stresses incurred during normal daily activities. Ulcerations develop in areas of excessive pressure, when joint deviations and bony prominences are susceptible to skin breakdown. Accommodative orthoses can be effectively designed to provide sufficient padding, redistribution of weight-bearing pressures, and slow and gradual healing (Figure 17-9).

Role of the Occupational Therapist

It is recommended that the therapist provide personal education (visual skin inspection) for individuals with insensate feet. Handheld skin inspection mirrors are indicated for some clients with reduced lower extremity ROM to ensure full inspection of the plantar surface of the foot. Selection of appropriate shoes is an important consideration with FOs. Slip-on flats or loafers are not recommended because they allow heel pistoning (sliding up and down in the shoe) and do not provide adequate counterpressure over the dorsum of the foot to maintain the foot securely in the shoe. Lace-up or Velcro-closure shoes are preferable because they provide added security.

Other shoe features that assist in accommodating the bulk of FOs include removable insoles, padded heel collars, and higher heel counters. Some athletic shoes feature nylon heel loops to assist in donning and doffing with ease. Long-handled shoehorns may be indicated for people with limited ROM.

Ankle/Foot Orthoses

AFOs are designed from metal and leather, thermoplastics, and laminates. Most AFO designs incorporate a foot plate to control the foot and ankle complex, a solid or jointed ankle (depending on the desired control), and a calf section to provide mechanical leverage for ankle and knee control. Metal and leather designs can be attached externally to a shoe or can incorporate a foot plate to fit within the shoe. Thermoplastic and laminated AFO designs use a molded foot plate to improve mid-tarsal and subtalar joint control, as well as to improve aesthetics and allow different shoes to be worn with the orthosis. It is important to note that when changing shoes a common heel height must be maintained. As with most orthotic designs, AFOs are available in prefabricated, custom-fitted, and custom designs.

A basic AFO is diagrammed inFigure 17-10, which shows the standard components. The proximal trim provides leverage for foot control during swing and is contoured to provide appropriate pressure around the soft tissue of the calf. The anterior opening allows for donning and doffing while the anterior closure secures the orthosis to the limb. The closure mechanism may vary, depending on the manual dexterity of the person. The anterior and ankle trim lines relate to the flexibility or rigidity of the orthosis. Specifically, wider trim that covers more anatomic area generally creates a more rigid orthosis and narrower trim creates a more flexible orthosis. The trim lines can be adjusted throughout the course of the rehabilitation program. Finally, the length of the distal trim line contributes to the mechanical function of the orthosis by allowing or delaying rollover as needed.

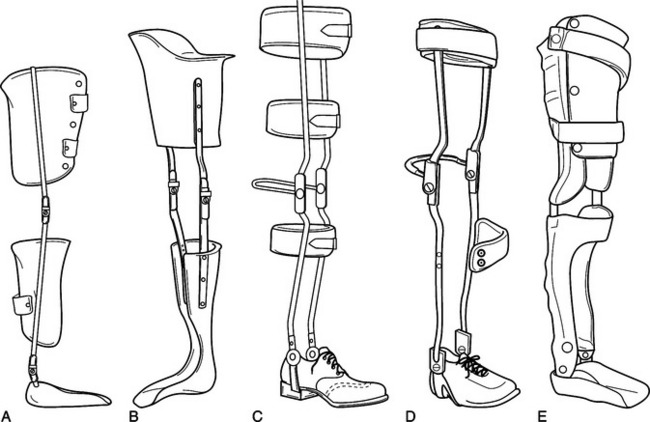

Figure 17-10 Various ankle/foot orthosis designs. (A) Supramalleolar orthosis. (B) Jointed AFO with posterior plantar-flexion stop and full-length foot plate. (C) Posterior leaf spring. (D) Double-upright design with medial T-strap and dorsiflexion-assist ankle joints. (E) Solid ankle AFO with instep strap. (F) Laminated AFO with double-action ankle joints and pretibial shell. (G) Patellar tendon-bearing orthosis (PTBO) for load-bearing relief of the foot and ankle complex with carbon fiber reinforcements at ankle.

Biomechanical Function

AFOs are designed to structurally bridge the ankle joint, providing a stable base of support at the foot and control of the alignment of the distal leg segment. Direct control of the ankle joint and indirect control of the knee joint are achieved with the use of various ankle joint designs. AFOs can be used to enhance, limit, or negate ankle joint ROM, depending on the individual requirements of the person and the person’s unique gait pattern. Some AFOs are designed to encompass the foot and ankle complex only and are termed supramalleolar AFOs (SMOs).

General Indications and Contraindications

Lehmann and De Lateur [Kottke and Lehmann 1990] noted the primary reasons for AFO application: mediolateral stability of the foot and ankle during stance, dorsiflexion assistance during swing, plantar flexion assistance for propulsion during terminal stance, maintenance of knee alignment through stance, approximation of a more normal gait pattern, decrease in energy costs, and prevention of the development of associated joint deformities [Kraft and Lehmann 1992]. Personal safety is another important reason for AFO prescription, especially for the person with a changing pattern of neuromuscular control. Temporary or permanent use of an AFO may very well prevent an unnecessary fall for the person who has poor balance or even mild functional deficits (i.e., foot drop).

Design Options

As noted, material choices for AFO designs are numerous. Metal and leather AFOs require a tracing and a series of exact measurements for fabrication. Attachment to a shoe limits shoe wear options but can improve ease of donning for a person with lesser cognitive or lesser upper extremity functional abilities. This type of AFO contacts the foot (via the shoe) and the calf (via the calf band). Such limited anatomic contact may be indicated for the person with periods of fluctuating edema, although the potential application of force for joint correction is also limited. Metal AFOs may incorporate a leather T-strap to assist in coronal plane control of the ankle joint. Various metal ankle joints offer free, limited, or restricted ankle joint ROM (Figure 17-10).

Thermoplastic and laminated AFOs are fabricated from a mold of the person’s limb. The casting material is applied to the limb while the orthotist maintains and holds proper joint alignment of the mid-tarsal, subtalar, and ankle joints. Proper hip and knee alignment is also important during this procedure to obtain correct anatomic relationships. Removal of this cast provides a negative mold, which is then processed into a positive mold (“statue”) of the person’s limb. Careful and specific modification procedures enhance the effectiveness of the desired three-point force systems and relief of pressure to bony prominences. The thermoplastic material or liquid laminate is then vacuum-molded over the positive mold to create a unique and individual orthosis. (Note: The casting, modification, and fabrication procedures are similar for all thermoplastic and laminated custom orthotic designs.)

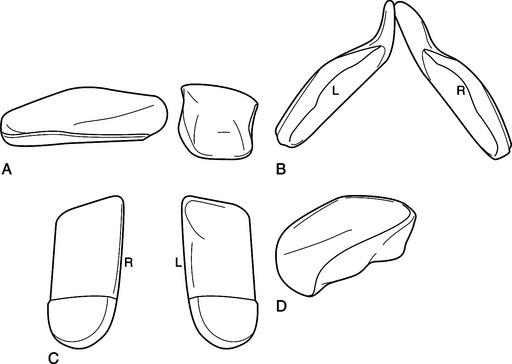

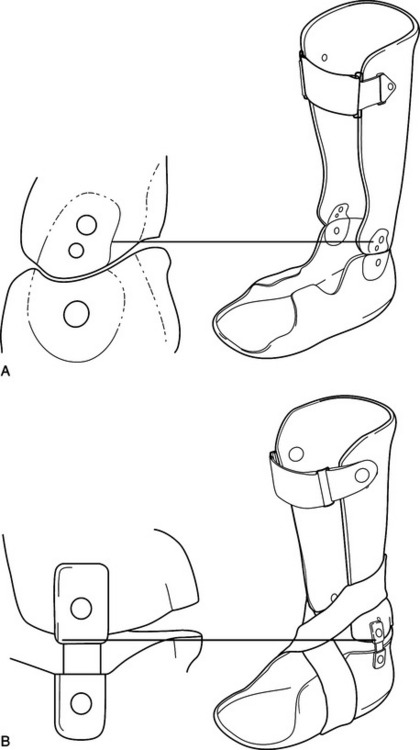

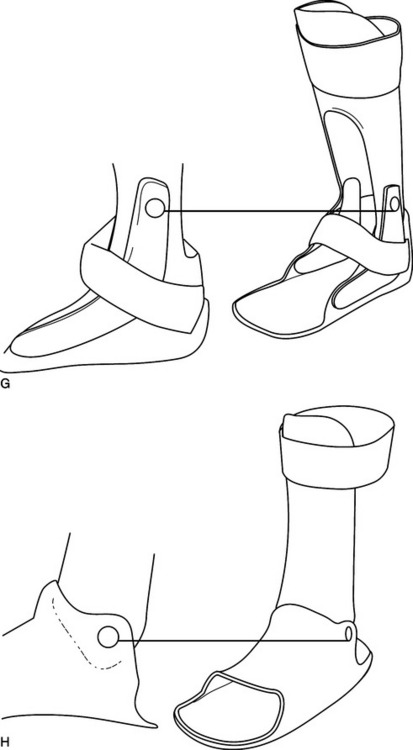

Ankle joints are now available in a variety of sizes, functions, and materials (Figure 17-11). Specially designed straps may be added to the orthosis to help maintain the foot within the orthosis or to shift the joint alignment. The flexibility or rigidity of the orthosis is determined primarily by the biochemical properties of the selected plastic. It is possible to create an orthosis with areas of rigidity and flexibility by altering the thickness of the plastic during the fabrication process. As always, a skilled orthotist can provide the necessary expertise in this area.

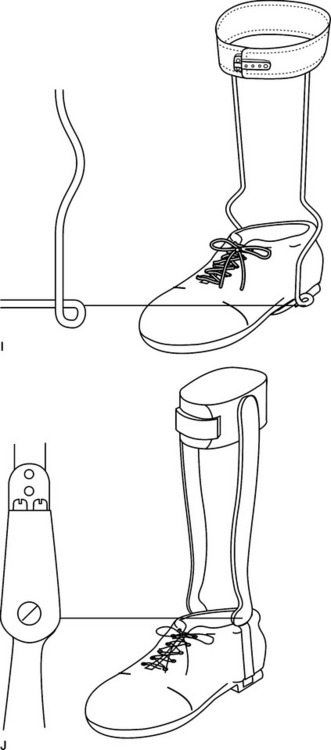

Figure 17-11 Various orthotic ankle joints. (A) Ninety-degree plantar-flexion stop, free dorsiflexion AFO with Oklahoma ankle joints. (B) Ninety-degree plantar-flexion stop, free dorsiflexion AFO with Gillette ankle joints. (C) Free-motion AFO with Gaffney ankle joints. (D) Dorsiflexion-assist AFO with Wafer ankle joints. (E) Dorsiflexion-assist AFO with overlap ankle joints. (F) Adjustable posterior stop AFO with Oklahoma ankle joints. (G) Floor reaction AFO with carbon inserts for ankle reinforcement. (H) Posterior-entry 90-degree dorsiflexion stop, free plantar-flexion AFO with overlap ankle joints. (I) Metal dorsiflexion assist. (J) Metal double action for dorsiflexion and lantar-flexion control.

Specific Applications

A person with a recent cerebrovascular accident (CVA, or stroke) can present with a varied neuromuscular picture. Generally, the involved limb presents with complete flaccidity (i.e., hypotonic) or extreme rigidity (i.e., hypertonic), but the tone may fluctuate with periods of both throughout the day. An orthotic prescription recommendation is often difficult for this group, as the tendency is to prevent “overbracing” of a person with expected functional return. However, delay of bracing often promotes the development of compensatory and inefficient gait patterns as well as deformities that are often difficult to resolve, even after some functional control has returned. An appropriate orthotic design is one that provides immediate stability and safety, with ongoing adjustability to substitute for only those functions that are still lost (Figure 17-12). An effective orthosis should not prevent functional muscle groups from returning to their normal roles.

Figure 17-12 CVA person with equinovarus and a cerebral palsy child with crouched gait. (A) Person recovering from a CVA presents with tone-induced equinovarus. (B) Child with cerebral palsy presents with mild crouching, drop-foot, and poor balance.

A person with cerebral palsy requires an intensive and integrated rehabilitation team approach from a very early age. Effective stretching and strengthening exercises maintain ROM and enhance potential ambulation abilities. Functional orthoses will be designed to help promote delayed age-appropriate activities, such as knee standing and pull-to-stand. Once the child is standing, functional abilities and walking patterns are evaluated and new orthotic prescriptions may be required. Effective biomechanical alignment and stability are balanced against functional mobility to prevent joint deviation and ligamentous laxities while allowing the child to explore the environment. It is often very difficult to achieve maximum outcomes in both structural stability and functional mobility. Compromises must be understood and discussed by the rehabilitation team.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

AFO design options can positively or negatively influence occupational performance tasks. Although rigid ankle designs provide biomechanical alignment and maintain joint corrections, this design also completely restricts ROM. Such activities as operating an automobile gas pedal, kneeling, bending at the waist, or using stairs can be difficult to achieve with a rigid ankle AFO. Conversely, an articulated AFO design provides obvious advantage in functional mobility, but it may compromise some individuals’ sense of balance and security. Often, a person is required to stand for long periods of time at work or meal preparation, and low endurance may contribute to knee buckling and loss of balance. Articulated AFO designs do not provide the plantar-flexion/knee-extension couple that rigid ankle designs offer, thus affecting knee stability.

For those people concerned with professional dress standards, the cosmetic appearance of the AFO may make a critical difference in acceptance of the orthosis. Although both metal and thermoplastic AFOs are designed to be worn under clothing, metal AFOs are wider at the ankle, offering a higher profile with metal ankle joints that are visible to others when the person is sitting. Plastic AFOs contour intimately at the ankle, offering a lower profile, and are not as obvious to others (especially when a translucent thermoplastic is used for fabrication).

Knee Orthoses

Knee orthoses generally fall into three categories: prophylactic, postoperative, and functional [Bunch et al. 1985, Kottke and Lehmann 1990, Goldberg and Hsu 1997]. Prophylactic knee bracing focuses on the prevention of injury or the reduction of the severity of injury for those persons involved in high-impact or contact sports. Postoperative or rehabilitative knee orthoses are prescribed after a surgical procedure, usually ligament reconstruction, to limit ROM while soft-tissue structures are allowed to heal. Functional knee orthoses are designed to provide mechanical stability to the chronically unstable or reconstructed knee joint.

Biomechanical Function

Knee orthoses are designed according to the mechanical principles of hydrostatics, levers, and force systems. Hydrostatics refers to tissue containment. In other words, the orthosis must contain (or “hold”) the flexible thigh and calf tissues so as to stabilize the knee joint and limit excessive stresses to the ligamentous structures. Fit, joint alignment, and suspension are critical factors in the effectiveness of any knee orthosis. It is extremely important for the mechanical joint of the orthosis to closely mimic the alignment and function of the anatomic joint. If the orthosis is not suspended and maintained in the proper position, joint alignment is sacrificed and often a discrepancy is created between the anatomic and mechanical joint axes. Specially designed straps, supracondylar pads, or inner sleeves help prevent distal slipping of the orthosis during daily activities.

Levers and force systems also play an important role in this process. As noted previously, the farther the points of force application are from the joint the longer the mechanical levers and the greater the mechanical effect of the three-point force systems. (SeeFigure 17-7 for an effective three-point force system to resist genu valgum.) If the orthosis slips distally during normal wearing, the length of the proximal levers has been shortened and the anatomic and mechanical knee joint discrepancy is dramatic. To receive maximum benefit from the orthosis, the person must perform proper donning techniques and periodic checking of the alignment of the orthosis throughout the day.

General Indications and Contraindications

Prophylactic knee orthoses are intended to prevent injury to the knee or to reduce the severity of injury for competitive athletes. Postoperative orthoses control ROM and encourage early weight bearing and limited activity. Functional knee orthoses are prescribed for chronically unstable knees and as an adjunct to many surgical procedures. Soft neoprene or elastic knee sleeves are generally prescribed to provide circumferential compression of the knee, warmth, and minimal medial/lateral stability.

Knee orthoses provide support in the coronal plane by preventing genu varum and genu valgum. Mechanical joint design and joint settings limit the available range of flexion and extension in the sagittal plane. Limited transverse plane control is available for attempts to “grasp” the thigh and calf sections through soft-tissue containment. Most important, the foot and ankle complex remains free to transmit internal and external rotation proximally to the knee during weight bearing. The hip joint also has available joint motion in all three planes and most often follows the alignment imposed distally at the base of support.

The knee is a complex joint with the motions of flexion and extension occurring about a changing anatomic axis. The exact motion of the knee joint has yet to be duplicated in mechanical joint designs, although many joints are quite sophisticated in their function. Mechanical joint options are discussed further in the knee/ankle/foot orthosis section of this chapter.

Design Options

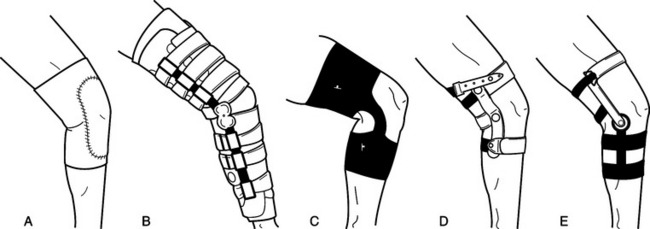

Over the past 20 years, increasing awareness in the prevention and support of the injured knee has led to the development of many orthotic designs. Each custom knee orthosis is measured, casted, designed, and fitted to meet the unique requirements of the person’s knee (i.e., anterior cruciate instability, medial collateral instability, hyperextension, and so on). Design features include reduced weight, colors and fabrics, and variable joint functions. Other options include specific sports applications for skiing and motocross. Despite the flood of orthotic designs and claims by the various manufacturers, no specific knee orthosis or brand has demonstrated clear superiority over any other design. An effective orthosis is selected according to the unique mechanical and functional needs of each person (Figure 17-13).

Figure 17-13 Various knee orthoses. (A) Soft neoprene knee sleeve. (B) Postoperative knee orthosis controls flexion ROM and extension ROM with adjustable joints. (C) Prophylactic knee orthosis with lateral joint. (D) Rehabilitative design to control knee hyperextension. (E) Custom knee orthosis to stabilize injured knee.

Specific Applications

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative condition that commonly affects the knee joint. Deterioration of the medial or lateral knee joint structure leads to genu varum and genu valgum deformities, respectively. People with severe joint deviation are considered for total joint replacement. Still, some people are not surgical candidates or may present with the early stages of the disease process. Such people may benefit from functional knee orthoses. These orthoses incorporate long mechanical lever arms to apply corrective forces to the affected knee joint. When a valgum or varum stress to the knee is induced, the medial or lateral compartments can be unloaded. Decreased pain and prevention of continued deformity are obvious benefits of this type of orthotic treatment program until such time as surgery is warranted (Figure 17-14).

Figure 17-14 Osteoarthritis. (A) Persons with diagnosis of osteoarthritis and genu varum may benefit from a custom knee orthosis. (B) Person with diagnosis of osteoarthritis and left-side genu varum and right-side genu valgum.

Competitive athletes and active individuals enjoy the challenge of various levels of physical activity. Unfortunately, when created circumstances subject the knee joint and soft-tissue structures to repetitive high-load stresses injuries can occur. Knee orthoses serve as an adjunct to surgical restoration and rehabilitation programs by limiting ROM and excessive stresses postoperatively.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

People receiving functional knee orthoses to prevent further knee deformity may also suffer from upper extremity degenerative changes that limit hand function. Although most knee orthosis designs use Velcro closure systems as opposed to traditional strap and buckle systems, medial or lateral placement of closure system loops is critical to enhance available functional dexterity. Closure systems that include a wider chafe opening allow the person with impaired hand function to feed Velcro straps through the opening with less difficulty.

Knee orthoses are generally designed to provide a total surface contact and are worn as close to the skin as possible. Don/doff procedures should be reviewed with the person to ensure that the most effective dressing routine has been established. Knee orthoses typically restrict anatomic knee flexion by 20 to 30 degrees because of the thickness of the posterior calf shells or straps. This ROM loss may impede certain work or leisure activities that require deep knee bends or squatting.

Knee/Ankle/Foot Orthoses

KAFOs are built on the same concepts that have been covered for ankle/foot orthoses. Structurally, KAFOs continue proximally by bridging the knee joint and containing the thigh tissues. Most KAFOs are custom made from measurements or casts and are fabricated from metal and leather, thermoplastic, or laminate materials. Hybrid designs incorporate a variety of materials to achieve the desired orthotic control. Some prefabricated designs are available for temporary use.

Biomechanical Function

KAFOs are successful in improving stability and functional mobility for persons with lower limb involvement. KAFOs are designed for persons with significant genu valgum, genu varum, genu recurvatum, or genu flexion (i.e., anterior collapse). As a result of structural bridging of the knee joint, improved coronal and sagittal plane control are achieved. Transverse plane control is determined distally by the foot plate design. Skeletal joint alignment of the knee is achieved by applying corrective forces through the soft-tissue structures of the thigh. Therefore, a well-molded and well-fitted thigh shell is an important component of the orthotic design. Excessive gapping reduces the mechanical effect of the design and reduces potential stability and function.

General Indications and Contraindications

When an AFO is ineffective in maintaining the knee over the base of support throughout the gait cycle, consideration of KAFO application is required. The knee is identified as the primary joint of instability, usually in combination with any number of neuromuscular involvements or functional deficits. Ideally, externally applied forces realign the knee over a stable base of support and normal joint motion is provided through mechanical joint structures.

In some cases, however, full correction or “ideal alignment” is not possible because of the long-standing nature of the deformity. Bony changes and musculoskeletal contractures at the hip, knee, and ankle present unique challenges for orthotic intervention. Donning and doffing abilities and individual functional activities must be evaluated to develop the most appropriate orthotic prescription.

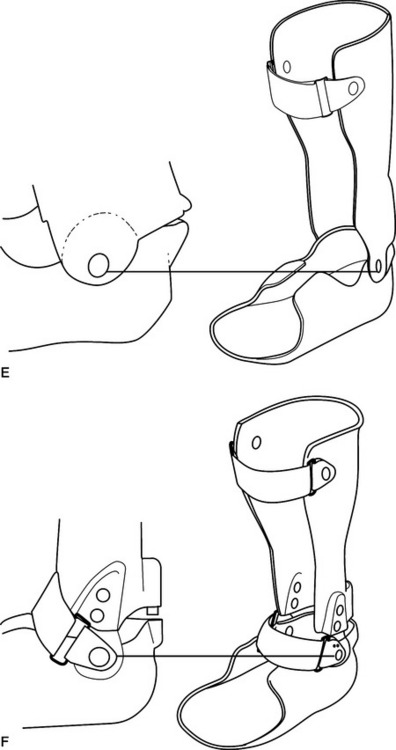

Design Options

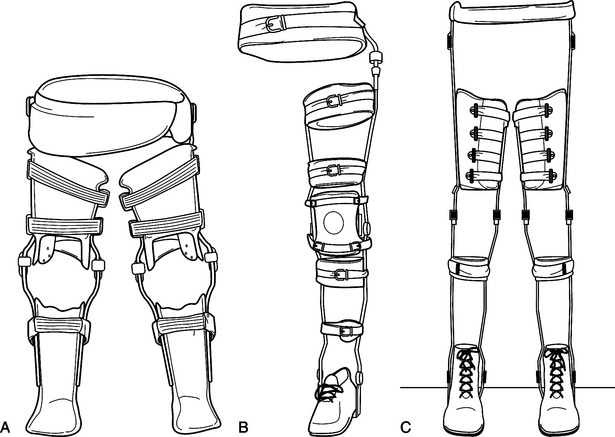

As with the AFO, there are many material and component choices available for KAFO designs, and material selection is generally based on the height, weight, activity level, and functional requirements of the person (Figure 17-15). Metal and leather, thermoplastic, laminated, and hybrid designs offer a variety of design options for the person with significant knee joint instability. Because the knee is the primary joint of involvement, mechanical joint selection warrants attention at this time.

Figure 17-15 Various knee/ankle/foot orthoses. (A) Thermoplastic orthosis with molded foot plate, jointed ankle, long anterior tibial shell, drop locks, and circumferential thigh shell. (B) Thermoplastic orthosis with molded foot plate, solid ankle, drop locks, and quadrilateral thigh shell. (C) Double-upright orthosis attached to shoe, with jointed ankle, posterior calf band, bail lock knee, and two posterior thigh bands. (D) Scott-Craig orthosis with double-action ankle joints, pivot anterior tibial band, bail lock knee, and posterior thigh band. (E) Laminated orthosis with molded foot plate, double-action ankle, pretibial shell, free knee, and posterior thigh shell with long anterior tongue.

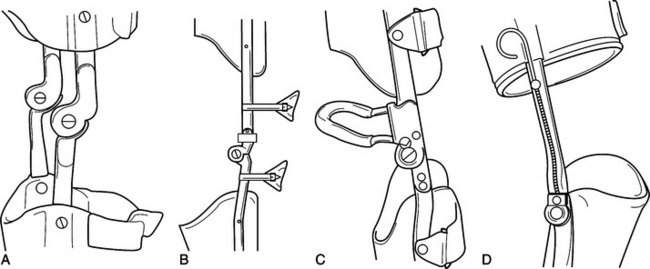

Knee joints come in a variety of sizes and functions that provide free, limited, or restricted joint motion. Common locking mechanisms include the drop lock and bail lock designs. Drop locks are designed to fall into place over the mechanical hinge when the person stands. These locks must be lifted by hand before sitting (or any activity that requires knee flexion). Bail locks are designed to snap into place and lock the knee once the knee is extended. The joints must be unlocked before sitting and can be disengaged by bumping the posterior lever mechanism on the seat of a chair.

The person does not have to bend over and manually unlock the joints. Step-lock joints provide a variable range of motion and locking capability. This joint design can be used with a progressive stretching program to reduce a knee flexion contracture. It is important to note that energy costs increase approximately 20% when one walks with a locked knee [Kraft and Lehmann 1992], and therefore locked knee KAFOs should be used cautiously. Orthotists are well versed in the various designs and can provide specific pros and cons relative to the individual person.

Single-axis, polycentric, and offset joint designs refer to the pivoting motion and alignment of the mechanical joints. A single-axis joint functions as it is named, with a single hinged action. Polycentric joints produce a shifting axis in an attempt to mimic the functional motion of the knee joints. Offset knee joint designs shift the mechanical axis posteriorly to the anatomic joint axis. This provides improved stance-phase stability and resistance to anterior knee collapse. Size, weight, function, and durability are important factors in knee joint selection.

The most proximal component of the KAFO is the thigh section. Thigh designs are critical to the success of the orthosis. Posterior shells with anterior straps, anterior shells with posterior straps, and full circumferential shells are common thigh section designs. The thigh shells may be fabricated of rigid or flexible material. Narrow medial/lateral (M/L) and quadrilateral-shaped thigh sections are the most common designs, but all thigh sections are contoured to the unique characteristics of each individual. The thigh shell may also be designed to “unweight” or “unload” the lower limb by providing a shelf for the ischium to sit on in combination with soft-tissue containment of the thigh muscles. This is similar to the prosthetic socket design for above-knee amputees.

Recent technological advancements in orthotic componentry have introduced stance-control orthoses (SCOs), which are mechanical knee joints for use with knee orthoses and knee/ankle/foot orthoses. These mechanical joints are available in several designs. Common features are free motion during swing phase and flexion control during stance phase. These stance-control knee joints allow a more normal gait pattern because the knee is not required to be locked during both swing and stance to prevent stance-phase flexion.

This design has a significant effect on the reduction of energy costs during walking because the swing-phase flexion negates the need to circumduct and/or hip hike on the involved side or vault on the contralateral side in order to obtain ground clearance. The ideal candidate for a SCO presents with isolated unilateral quadriceps weakness, a relatively sound contralateral side, minimal contractures, minimal spasticity, and good hip and ankle musculature. People should be thoroughly evaluated by the rehabilitation team for potential application of the SCO.

Specific Applications

Genu recurvatum is a common involvement for KAFO application. Specifically, knee joint laxity allows the anatomic knee center to move posteriorly during weight bearing. This is usually an acquired deformity that develops secondarily to weakness of the quadriceps or posterior calf muscle groups. It may also develop secondarily to a plantar-flexion contracture at the ankle. With associated muscle weakness, anterior collapse of the knee would occur. Therefore, the person learns to compensate by maintaining the knee posteriorly and shifting the body weight anteriorly through hip flexion and anterior trunk lean. The effect is to place the body weight in front of the knee joint to prevent collapse and falling. A plantar-flexion contracture forces the knee posteriorly during initial loading and continues to disrupt forward progression throughout stance phase. In either case, load-bearing stresses cause permanent damage to the posterior capsule and soft-tissue structures of the knee, the deformity continues to progress over time, and energy costs increase dramatically. The potential for the development of a severe deformity with permanent damage to the knee requires prompt attention.

The objective of a KAFO varies for persons with genu recurvatum (Figure 17-16). In some orthotic designs, complete sagittal plane correction is the goal as long as there is a mechanical means of providing stance-phase stability to prevent anterior knee collapse when weakness is noted. For other persons, partial correction will reduce the deforming forces to the knee and limit progression of the deformity. Individual evaluation and assessment determine the appropriate design criteria.

Figure 17-16 Genu recurvatum. A person with severe genu recurvatum is a candidate for a KAFO design.

Coronal plane deviations of the knee have been shown inFigure 17-14 and examined in the discussion of knee orthoses and osteoarthritis. If the mechanical leverage provided by the knee orthosis is not sufficient, it may be necessary to consider a KAFO design. By crossing the ankle and subtalar joints and encompassing the foot, it is possible to achieve greater coronal plane control and stability of the knee joint. Several knee joint options are shown inFigure 17-17.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

The choice of a KAFO knee extension locking mechanism is perhaps the most significant threat to occupational performance in lower extremity orthotics. Although locking of the knee during walking should be avoided whenever possible to reduce increased energy expenditure, it may be unavoidable for many persons who require stability and are at risk of falling because of weakness or imbalance. For improved cosmetic appearance and to maintain total surface contact, it is recommended that KAFOs be donned under clothing. However, manipulation of locking mechanisms, specifically drop locks, is infinitely more difficult when the mechanism is visually hidden under a layer of clothing and tactile feedback is reduced.

For the person who wears the KAFO only for specific tasks during the day and removes the device to be more comfortable, wearing the KAFO on the outside of clothing may be advisable. Care should be taken that such a person accepts the cosmetic ramifications and that biomechanical design is not compromised. It is important that occupational therapy evaluation of occupational performance be completed before the orthotist begins fabrication, as KAFO measurements will differ significantly over as opposed to under clothing.

Knee extension locking mechanisms include drop locks, bail locks, and trigger locks. Drop locks are the most commonly used mechanisms and are disengaged by using palmar or lateral pinch just before sitting. This task requires the person to bend forward, reach down, and use significant pinch strength to unlock mechanisms on both the medial and lateral aspects of the knee. Poor balance, limited upper extremity range, or reduced hand function may prevent independent operation of the unlocking mechanism. This population would be at a significantly higher risk of falls when using a KAFO with drop lock mechanisms.

Bail locks do not require the person to bend forward, reach down, or use any hand involvement to manipulate the mechanism because the knee lock is released by the application of slight pressure to the posterior knee loop of the KAFO from the front edge of a chair. Bail lock designs are dependent on a stable chair with a hard front edge to operate efficiently. The height of the chair is also an important factor if the person is to reach the lock effectively. It is not practical to disengage this type of lock against soft-surface furniture, such as sling wheelchair seats, couches, beds, or recliners. This limits the bail lock’s scope of usefulness within the home environment. Tight clothing donned over the KAFO with bail locks may interfere with secure operation of the mechanism.

Trigger locks are a hybrid design that includes elements of both drop lock and bail lock mechanisms. This design employs medial and lateral locks connected to a common cable mounted on the proximal lateral aspect of the thigh. Minimal reaching, bending, and hook hand strength is required to operate this type of mechanism. This device is not dependent on furniture for efficient operation, and safe operation of the device is not impaired by clothing.

Each person should be carefully evaluated by the therapist in concert with other team members before a final decision is made regarding which knee extension locking device is employed. Occupational performance factors often play a key role in selection criteria.

Hip Orthoses

Hip orthoses are prescribed for problems associated with the femoral head or acetabulum. Custom-fitted and custom-molded orthoses consist of a pelvic section, hip joint(s), and thigh cuff(s) to control ROM and alignment. Occasionally a shoulder strap is used to assist with suspension of the orthosis. Orthoses may be designed to provide unilateral or bilateral control of the hip and are most often used to promote healing postoperatively. Hip orthoses are also used to provide a wider and more normal base of support for sitting, standing, and walking. This creates increased stability for functional activities and aligns the lower limbs for more effective biomechanical function.

Biomechanical Function

The hip joint is a universal ball-and-socket joint with available motion in all three planes. Many orthoses control abduction/adduction and flexion/extension. If internal and external rotational control is needed, a long leg extension may be included in the orthotic design. Congenital hip disorders are frequently diagnosed at or soon after birth and require proper positioning to encourage normal bone development and alignment and proper angulation of the head, neck, and shaft of the femur. Acquired or degenerative disorders may require precise positioning and control to decrease pain and limit excessive forces transferred through the joint. As the hip joint is the dynamic link between the trunk and leg segments, misalignments and dysfunctions at this joint affect pre-positioning of the limb for stance and exacerbate large truncal deviations throughout the gait cycle.

General Indications and Contraindications

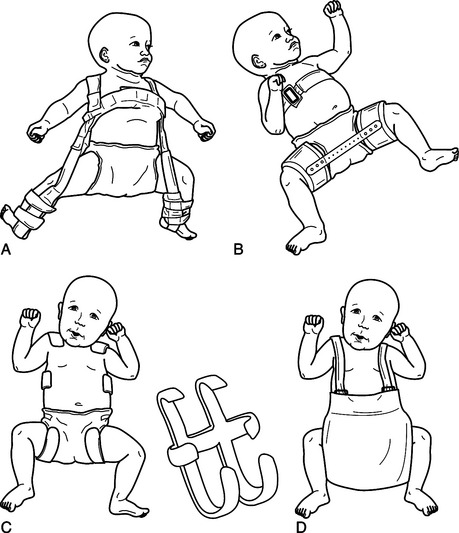

Hip orthoses may be used for congenital, dysplastic, traumatic, degenerative, or post-surgical procedures [Goldberg and Hsu 1997]. The Pavlik harness, Ilfeld orthosis, Von Rosen orthosis, and Frejka pillow are all used for developmental problems associated with dysplastic hip joints (Figure 17-18). These designs are used to realign the femoral head in the acetabulum to prevent continued dislocation and developing laxities. Legg-Perthes disease is a disorder presenting with osteochondrosis of the head of the femur and several orthoticdesigns have been developed to treat the affected pediatric population. Hip orthoses may also be used postoperatively after total hip replacement to control ROM and often to serve as effective “reminders” to maintain proper positioning during daily activities (Figure 17-19).

Figure 17-18 Various hip orthoses (note options). (A) Pavlik harness. (B) Ilfeld orthosis. (C) Von Rosen orthosis. (D) Frejka pillow.

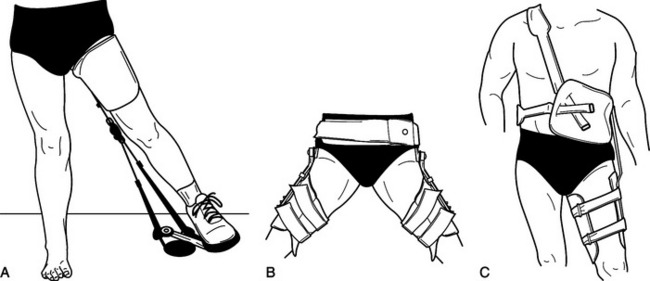

Figure 17-19 Legg-Perthes orthosis and total hip replacement orthosis. (A) Legg-Perthes orthosis. (B) Bilateral hip abduction orthosis with pelvic band. (C) Unilateral hip abduction orthosis with pelvic girdle and shoulder strap.

Many children with spasticity develop hip instability and pain, requiring either soft-tissue release of the adductors, flexors, and internal rotators of the hip or more complicated bony osteotomies of the pelvis or femur. Often hip spica casts are used postoperatively to maintain the surgical correction. Recently, pediatric hip orthoses have been used in some cases to replace hip spica casts. Hip orthoses are usually equipped with two sets of liners that can be washed daily to eliminate odor and improve hygiene. When the hip orthosis is no longer used 24 hours per day, it is sometimes used as a functional orthosis during the day or a positioning orthosis at night.

Design Options

Pediatric and adult populations require different orthotic approaches. In pediatrics, orthoses are designed to maintain good alignment during the normal growth processes of bone modeling. Controlled forces through the hip joints promote normal development of the head of the femur and the acetabulum. Hip orthoses for adults usually address the degenerative effects of joint deterioration. Clients with degenerative conditions are usually placed in orthoses that limit ROM in order to support and control compromised muscles and to prevent dislocation following primary or revision surgery.

Specific Applications

Although recurrent hip joint dislocation after surgical repair is rare, occasionally external support may be required for complicated procedures, revisions, or poor surgical outcomes. The joint of the hip orthosis is designed to provide variable alignment options as the person progresses through the rehabilitation process. Usually, the joint is aligned to maintain the hip in 10 to 20 degrees of abduction [Goldberg and Hsu 1997]. This helps to hold the head of the femur in the acetabulum.

Flexion and extension ranges are limited to prevent anterior or posterior dislocation while allowing the person to sit and walk. Internal and external rotation control is limited to some degree by “grasping” the soft tissue of the thigh. Proper fitting and adjustment and proper donning of the orthosis are critical to maximize function and effect. A shoulder strap is sometimes used to suspend the orthosis and maintain proper mechanical and anatomic joint congruency. A hip orthosis may also be ordered if the client has already dislocated the hip. The orthosis is usually worn for 3 to 6 months at all times to allow the soft tissue to heal and to serve as an effective kinesthetic reminder to maintain proper positioning during daily activities.

Dysplastic joints in the pediatric population present in varying degrees of severity. Legg-Perthes disease occurs more commonly in young boys and is identified as osteochondrosis of the femoral head. In the beginning of the disease process, occlusion of blood supply to the head of the femur promotes necrosis. Revascularization eventually occurs within the plastic bone. However, the bony contouring of the femoral head does not develop normally. Continued weight-bearing stresses increase the deformation of the hip joint and can result in permanent disability. Various hip orthoses have been designed to specifically treat this disease (Figures 17-18 and 17-19). As with most hip orthoses, this type of orthotic treatment program is temporary.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

After total hip arthrodesis (THA), hip abduction orthoses are commonly prescribed to limit ROM and promote healing. These devices are usually worn 24 hours per day for several weeks after surgery. Clothing is worn over the orthosis so that the client’s hip is controlled at all times. Posterior dislocation is the most common type of dislocation and is most apt to occur with the hip positioned in flexion greater than 90 degrees internal rotation and adduction. Occasionally, the hip may dislocate in an anterior direction <15% of dislocations). An anterior dislocation will also require a different set of hip precautions and a hip orthosis that has a long leg component attached to control rotation and hip extension.

Typically, persons require training in self-care activities such as dressing, bathing, toileting, and hygiene. Adaptive equipment (such as a reacher, sock-aid, extended bath sponge, extended shoe horn, and raised toilet seat) may reduce excessive hip flexion during hygiene and self-care. Most hip orthosis designs feature removable thigh and pelvic pads. These can be washed and hand dried quickly on a regular basis to prevent skin rash and breakdown.

Hip/Knee/Ankle/Foot Orthoses

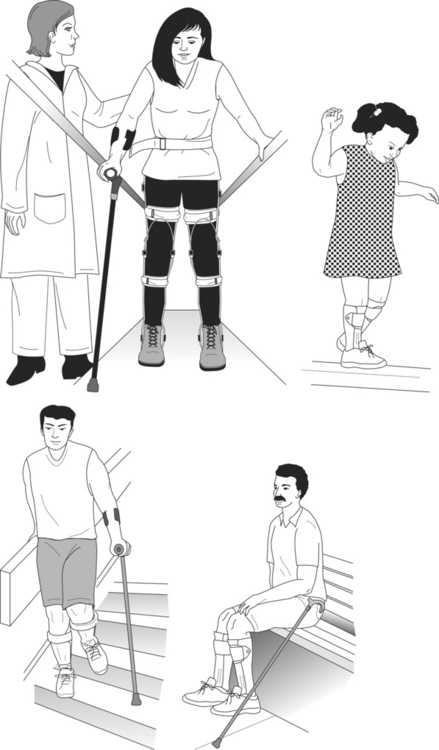

Hip/knee/ankle/foot orthoses (HKAFOs) build upon the basic concepts outlined for KAFOs. A mechanical hip joint(s) and pelvic band or pelvic/trunk section is added to provide additional control and stability. These are very complex orthotic designs that require the skills of an experienced orthotist (Figure 17-20). Evaluation, casting, measuring, fitting, and follow-up are keys to the success of such extensive orthotic designs. HKAFOs can be used for both daily activities and therapeutic treatment programs. Energy costs may prohibit use of this type of orthosis for all instrumental activities of daily living, and wheelchair mobility may be a better option for some persons. Still, young persons with congenital deformities desire the opportunity to socialize with their peers “eye to eye,” just as almost all persons with acquired trauma desire the opportunity to “walk” again.

Figure 17-20 Various hip/knee/ankle/foot orthoses. (A) Bilateral thermoplastic HKAFOs. (B) Unilateral double-upright HKAFO. (C) Bilateral double-upright HKAFOs.

Biomechanical Function

HKAFOs provide varying levels of mechanical control. Most simply, the KAFO is attached to the pelvic band with a single axis joint used to control rotational alignment of the limb during swing. This allows proper positioning of the limb for stance. More complex hip joint designs promote a reciprocal gait pattern so that extension of one limb promotes flexion of the contralateral limb, and vice versa. These reciprocating gait orthoses (RGOs) are used in both pediatric and adult populations, primarily for persons with flail bilateral lower limb involvement. Good upper extremity strength and adequate trunk control are prerequisites for this type of complex orthotic design.

General Indications and Contraindications

HKAFOs control the hip joint alignment to pre-position the lower limb for weight acceptance. The hip or pelvic section may consist of a narrow band, or it may completely enclose the pelvis and trunk with a spinal orthosis that is then attached to the lower limb orthoses. The amount of bracing on the trunk segment depends on the functional abilities, control, and upper body strength of the person. HKAFOs are commonly prescribed for persons with spina bifida or spinal cord injury, or for any person presenting with a flail lower limb and limited hip control. Individual height, weight, strength, endurance, motivation, physical assistance requirements, donning abilities, and psychosocial situations must be evaluated with regard to the potential success of the orthotic program.

Design Options

The RGO is a unique design that makes ambulation possible for many persons who are unable to walk with the conventional HKAFO designs (Figure 17-21). The functions of the hip joints are coordinated and interdependent through a mechanical linkage. While standing, the person leans somewhat anteriorly to place the hip anterior to the distal base of support. Walking is initiated as the person pushes down with the ipsilateral arm while shifting the body weight toward the contralateral limb. As the limb is unloaded, it swings anteriorly, creating a slight forward momentum.

Figure 17-21 Reciprocating gait orthoses (note options). (A) Isocentric RGO. (B) Steeper advanced RGO (ARGO). (C) Fillauer cable design RGO.

Through the mechanical linkage, ipsilateral hip flexion encourages contralateral (or stance side) extension. At this point, the contralateral hip is positioned anterior to the distal base of support and the cycle begins in the opposite direction. With training, this gait pattern can be smoothed considerably and an effective means of walking can be developed for those persons with few or no other options. Mechanical maintenance of the orthosis is extremely important to maintain the components in good working order, thus effecting the smooth transfer of momentum from side to side.

Specific Applications

Persons with spina bifida and spinal cord injury may benefit tremendously from this type of orthotic intervention. Upright weight bearing is associated with improved cardiopulmonary function, bowel and bladder function, circulation, and bone density [Kraft and Lehmann 1992]. Children benefit from the social interaction with their peers and can alternate with wheelchair mobility as needed. Almost all adult persons with traumatic spinal cord injury retain the desire to walk as a primary goal throughout their rehabilitation program.

Unfortunately, not all persons are candidates for this type of orthotic intervention. Modular RGOs are now available to be used as evaluative tools in determining the appropriateness of orthotic application at this level. Adjustable units are custom fitted and loaned to the person on a temporary basis. This allows the person to receive gait training, improve upper body strength, and improve cardiovascular endurance. This is especially helpful in the person with questionable walking abilities who remains very motivated to pursue his or her walking potential. After a few weeks of training, definitive RGOs are then made to provide a more intimate fit and better control for the person.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

The potential success of the HKAFO program is dependent on many physical and biomechanical factors. The person’s occupational performance potential may well be of critical importance in the team’s decision to pursue HKAFO intervention. As previously stated, most persons identify ambulation as their primary rehabilitation goal. During intensive therapy, persons are likely to share their level of psychosocial acceptance with members of the rehabilitation team. The occupational therapist has ample opportunity to develop a level of trust during evaluation and training that allows the person to share feelings regarding the practicality of orthotic intervention.

HKAFO systems require much higher levels of energy expenditure, upper extremity strength, and endurance than many persons are able to maintain on a regular basis. Although it may be apparent to members of the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team that the person achieves much higher levels of functional independence when using a wheelchair for mobility, the person may still prefer to focus on ambulation as the primary goal. For many persons, the process of acceptance of the residual effects of disability may take many months or even years. The occupational therapist is in a unique position to help persons resolve these difficult issues in a supportive and encouraging manner.