Chapter 6 Leadership and management in midwifery

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

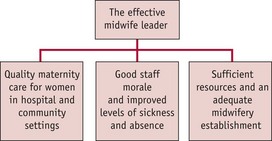

Government strategies for maternity services focus on the premise that all women and their families will have access to quality maternity services, designed to meet their individual needs (DH 2004, Scottish Office NHSiS 2001, Welsh Assembly 2005). The Maternity Services Survey (DH 2007c) revealed that 80% of women were satisfied with care they received during pregnancy and childbirth. Women also stated their preference for more choice regarding their care. In response, the Government published Maternity matters: choice, access and continuity of care (DH 2007b) with a renewed focus to improve the quality of maternity services. Safety, quality of care, choice and satisfaction are recognized as the key priorities for women and their families during their pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal experience (DH 2007b). To support its commitment to women, the Government has underpinned its strategy with a guarantee to all women regarding the quality of the care they will receive. Women will be offered choices in:

The key features of government policy are shown in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Maternity matters: choice, access and continuity of care (DH 2007b), indicating all choices are available to women.

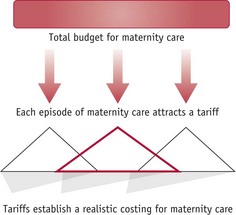

The key to the successful implementation of the government strategy is through effective dissemination across health authorities and with stakeholders who will engage with a commitment to operationalize the strategy. Consequently, midwives need to be aware of developments in their local maternity services (DH 2007b). In order for plans to be fully implemented, resourced, sustained, monitored and evaluated, effective midwifery leadership is fundamental for this agenda for change (Scottish Office NHSiS 2001). Additionally, the financial cost of maternity services must be accurately and realistically assessed so that resources may be provided for effective and efficient management (DH 2007b). In order to assess resources, each episode of maternity care – for example, an antenatal visit, delivery by caesarean section or normal postnatal inpatient care over a 24-hour period – is allocated a specific cost (tariff), thereby influencing the funding of resources (Fig. 6.2). The cost may be allocated regardless of geographical location but will need to take account of social issues that affect the resources required by women in the maternity services.

Whilst leadership and management of maternity services have been devolved, there are developments for national standards and objective monitoring frameworks to ensure quality of care and equity of provision for all women across the United Kingdom (DH 2007b). Improving the care given to women and their families is through preparation of the maternity services workforce, with investment in staff development and education (DH 2007b, Scottish Office NHSiS 2001). Midwife leaders and managers at each health service level are required and need to be prepared for their roles in management and leadership.

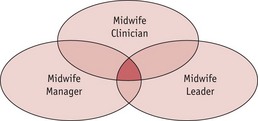

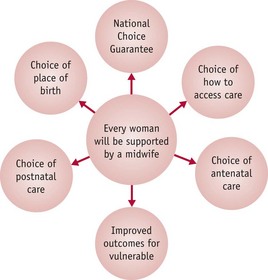

Whilst their role, responsibility and accountability is to ensure the quality and safety of care for women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period, midwives require leadership and management skills as key aspects of their role (Fig. 6.3). Midwives need to develop a critical insight and understanding of the theory and practice of leadership and management and its application to their practice, regardless of whether their practice is in the health service or independent sector. Acquiring leadership and management knowledge and skills will enhance effectiveness in the development of quality maternity services and the progression of the midwifery profession in the 21st century and beyond. Figure 6.3 shows how the functions within their role overlap.

A range of leadership theories will be explored, including examples of traditional and alternative approaches. Consideration is given to the application of appropriate theories and experiences in leadership and resource management to develop quality maternity services and sustain a workforce that feels valued, motivated and committed to the delivery of quality care.

The development of leadership and management theory

In leadership and management, there are variations in use and application of terminology. There are examples of literature where the terms management and leadership are used synonymously (Buchko 2007, Manning 2002, Muldoon & Miller 2005, Nienaber & Roodt 2008), and where the term management is used primarily with some reference to leadership (Ollila 2008, Ozcelik et al 2008, Pounder & Coleman 2002, Prosen 2008, Sadler-Smith & Shefy 2006), and where the term leadership is used predominantly. These sources identify the role of the leader as having primacy, with need for additional skill development in the management of resources (Buchanan et al 2007, Greenfield 2007, Guillory 2007a, Guillory 2007b, Hammett 2008, Turner & Mavin 2007, Wood & Winston 2007). Ackloff (1981) argues that the principles of leadership and management are interwoven, proposing an effective leader has to gain legitimacy, which is acquired through previous resource management success. A further degree of clarification is offered by French et al (2008), who suggest a simple distinction between management and leadership. The role of a manager within an organization is concerned primarily with ensuring stability and enabling the organization to run effectively. The role of a leader within an organization is to inspire the workforce and promote innovation and long-term change.

In making distinctions between the role of leader and manager, French et al (2008) indicate that the senior person is identified as leader. This distinction is useful in concepts for strategic and operational leadership and management terminology, for example, the strategic leader is considered the visionary and the most senior post, the operational manager ensures the effective utilization of resources to sustain the business. However, it is important to acknowledge that size and complexity in organizations may determine their leadership and management roles and responsibilities.

The terms strategic and operational appear to be widely utilized by organizations in determining a leadership and management hierarchy. Nonetheless, the roles of leader and manager are neither distinct nor clearly demarcated, and overlaps between the two are perhaps inevitable and unavoidable (Adair 2006). As the understanding of leadership and management has developed, it is increasingly acknowledged that the role of manager requires leadership skills regardless of the level of the management role within an organization (Adair 2006).

Leadership

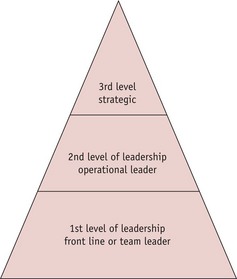

Adair (2006) advocates the use of the term leadership and suggests there are three levels of leadership (Fig. 6.4):

Whilst leadership theory has evolved since the beginning of the 20th century (Yukl 2005) and effective leadership is a key facet of an organization’s success, there is lack of clarity regarding what is an effective leader; however, what is clear is that there is no single style of leadership that works in all situations. Growing organizational complexity necessitates alternative leadership strategies to gain insight into the management of understanding and the principles of effective leadership (Ackloff 1981, Yukl 2005). Ackloff (1981) coined the term ‘contextual mess’ to describe the increasing complexity of work environments. Within an organization’s contextual mess and the complexity of health services, maternity services leaders and managers are faced with multifaceted challenges which appear to be underpinned by ambiguity, uncertainty and shifting priorities.

Traditional theories of leadership

Trait theory

Trait theory is considered the earliest documented approach of the study of leadership and can be plotted back to the early 20th century (French et al 2008). This theory attempts to capture the traits of recognized leaders in history, for example Napoleon and Churchill, and apply these traits to identify future leaders. Stogdill (1974) argued that there are specific identifiable traits which are linked to leadership success. These specific traits can be identified in leaders working within a wide range of professions and disciplines, including military services, law, business organizations and politics. Whilst research succeeded in the recognition of a number of common behaviours of established leaders, including charisma, intelligence and effective communication skills, it failed to recognize that there were also exceptions to the possession of these identified traits to be found amongst other successful leaders (Bass 1990, Stogdill 1974) (Fig. 6.5). Little consideration was given to the context of the situation in which a leader may find themselves, for example the difference between leading an independent midwifery group practice and a midwife leading/managing a maternity unit of over 9000 deliveries per annum. The skills of a leader may be situation- or context-specific.

Behavioural theory

In the 1950s, theorists considered a behavioural approach to leadership, through studying behaviours demonstrated by recognized leaders (French et al 2008). The theory suggested that an effective leader demonstrates specific behaviours and that leadership and effective resource management were central to maintenance and development of a successful organization. This could be applied to leadership and management in midwifery. Two research studies revealed two key behaviours of effective leadership (Bass 1990, Likert 1961):

Research into leadership identified that a distinct leadership style was of an employee-centred approach, and a second a production-centred approach. Effective performing organizations demonstrated high levels of employee-centred leadership. Leaders who were employee-centred demonstrated a higher level of production with a greater degree of employee satisfaction and positive morale (Likert 1961). Leadership behaviours were considered in terms of ‘human-relations-orientated’ or ‘task-orientated’ (Likert 1961). It was not clear from the results whether any of the organizations examined demonstrated leaders utilizing both distinct behaviours simultaneously or separately within the same organization and the potential impact on either employee or production.

An Ohio State University research study examined perceptions of leadership styles amongst the most senior organization staff. It revealed that leaders who were considerate to the feelings of employees or junior staff were deemed to be the more successful leaders. Those leaders who were orientated to the achievement of the task were less popular and did not maintain staff morale. The research later concluded that the most successful leaders demonstrated both behaviours, they were considerate of the workforce and their needs and also remained task-focused (Bass 1990).

It appears that a successful leader within an organization demonstrates in equal portions a concern for the workforce and concern for production. In midwifery, this would apply to leaders having a central concern for care of women and working within the team for the quality of service. Trait and behavioural theories may fail to recognize the potential conflicts that can arise between the workforce and production and how a leader deals effectively with conflict situations. If a successful business organization is faced with a downturn in the economy, the potential impact will be reduced production and a loss of revenue. In this circumstance, a leader may have to decide to reduce the workforce in order for the organization to survive. Therefore, in an economic crisis, priority will be given to sustained production, leading to conflict between the workforce and the service.

Behavioural theory and the midwife leader

In a healthcare setting, an effective midwife leader may find that restricted financial resources may result in an overstretched workforce, which leads to feelings of anxiety and being devalued. In addition, midwives and their colleagues may express concern that the quality of care may be compromised, leading to the additional dissatisfaction of women regarding their care. In a crisis situation, leaders increasingly find their skills and effectiveness being tested. Theoretical approaches to leadership may not be effective for a health service meeting changes.

Alternative leadership styles

Transformational leadership

Transformational leadership is determined by a leader demonstrating key characteristics, including charisma, and the ability to inspire and motivate staff in the achievement of a shared vision or goal. Through these characteristics, a leader will gain the trust and confidence of employees. Successful transformational leadership ensures the organization benefits from enhanced employee commitment and performance. Transformational leadership creates changes in an organization which can present the greatest challenges as the outcome of change cannot be fully predicted (Ackerman 1986). In a transformational change, reciprocal levels of trust and confidence are required between the workforce and the leader (Jick 1993). Therefore, leading changes in maternity services involves teamwork and staff participation.

Implementing transformational leadership may highlight a range of issues, such as unpredicted emotional behaviours, which challenges a leader’s self-awareness and the prospect of failure (Mitki et al 2008). Early recognition of unpredicted or adverse outcomes such as resistance of staff or the effects of changing a rostering pattern on part-time staff need to be addressed during a change process. The transformational process can be effective as it facilitates the leader’s positive influence over colleagues (Bass 1998). If managed effectively, change can result in individual and team performances beyond expectation with recognition by colleagues of effective transformational leadership in both the management of resources and productivity.

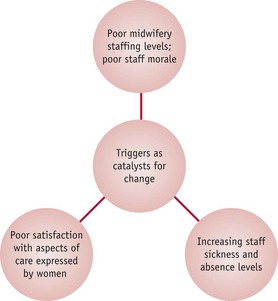

The effectiveness of sustained transformational leadership may be underpinned by robust trigger identification (Mitki et al 2008). Triggers in a maternity service are problem areas that require intervention, such as poor morale or complaints from women or families about the service (Fig. 6.6). Recognition of triggers in the workplace becomes a precursor for change and development. Triggers can also alert a leader to a potential conflict that, with prompt action, could be avoided. Transformational leaders will identify the need for alternative strategies and ways of working and support the workforce through change (Ackloff 1981, Mitki et al 2008). Nadler (1998) argues that a leader must recognize the potential magnitude of a trigger event in assisting colleagues to conceptualize and understand change, adapt to changing working patterns and recognize the need to change or redefine roles and responsibilities and so involve the staff in their development and to seek answers for change.

Ensuring all staff or those involved in the process learn about a change that is to take place is a key point to its successful outcome. Effective leaderships will create a responsive climate to changes (Fig. 6.7). The capacity to learn and the establishment of a learning process are critical during a transformation process and the key element to determining successful outcome (Mitki et al 2008) – for example, all staff understanding new implementation of polices in relation to a change in care for women in labour. Careful attention to the learning process and support of colleagues’ needs will underpin the successful implementation of new structures, changing working patterns and the development of leadership styles (Mitki et al 2008, Senge 1990). For transformational leadership to be successful it is essential that leaders monitor colleagues’ understanding of the change and encourage their contribution to the process.

Transformational leadership in contemporary midwifery practice

There is a place for transformational leadership to bring about effective implementation of government strategies and quality, safe maternity services (DH 2007a), as well as maintaining a motivated workforce. Midwives possess a shared vision; they aim to support women in their choice of care, and midwife leaders must work with Government, and stakeholders, such as local commissioners and providers of healthcare, to ensure that maternity services are fully resourced to meet the government’s guarantees to women (DH 2007a). Midwife leaders in clinical practice can initiate and motivate midwives to change, by demonstrating transformational leadership characteristics. With expertise and experience, they recognize triggers for change (Fig. 6.6), including poor staffing levels, increasing staff sickness and absence, poor staff morale and poor satisfaction of aspects of maternity care expressed by women and their families.

Competence-based leadership and supervision

Leadership and resource management involves a complicated mechanism of human and social interactions that requires an understanding of human relationships and conflicts as well as problem-solving skills (Ollila 2008). An organization’s leadership and resource management strategies are most effective when human actions are supported and valued (Sveiby 1990). The success of an organization is primarily the outcome of human actions that include motivation, ability and commitment. In addition to the establishment of leadership and management strategies, Sveiby (1990) suggests there are three key factors underpinning an organization’s effectiveness:

When these three factors work in harmony underpinned by effective leadership and resource management strategies, then an organization is able to develop and deal with change (Sveiby 1990). The future of healthcare services is dependent on effective leadership and resource management in order to achieve the government healthcare agenda and to develop and utilize competence and skills in order to improve the quality of healthcare, including maternity services.

Sanchez & Heene (2004) and Sanchez (2004) suggest strategic leadership and resource management is established on the premise that there is a possibility for change. Change initiates an appraisal of the competencies that exist within an organization and a consideration of the competencies that need to be acquired in order to meet the strategic goals for change and development. Durand (2000) suggests competence comprises a range of skills an individual utilizes to complete a given task. Competence is based upon knowledge, skills and attitudes and forms the cornerstone to a successful organization.

Competence-based resource management focuses on the recognition of knowledge and skills, and the refocusing of this knowledge and skills to meet the organization’s goals and aspirations, for example training the workforce in new techniques for antenatal screening. A leader must recognize the need for established competencies within the organization and also anticipate the requirement to develop new competencies to move the organization forward (Fig. 6.8) (Ollila 2008, Sanchez 2004). Utilization of a competence-based management structure is central to the maintenance, continuous assessment, evaluation and redefinition of the organization’s core competencies to ensure continued success (Ollila 2008, Sanchez 2004).

Statutory midwifery supervision

In the UK, supervision is central to effective leadership and competence-based resource management (Ollila 2008), enabling support for strategic development of roles within any organization (Sanchez & Heene 2004). Without supervision, leaders face dissatisfaction with their role, incompetence and eventual burnout. Organizations should consider the role of supervision as both preventative of leader burnout and effective in maintaining the wellbeing and efficiency of leaders and managers (Ollila 2008). Supervision within an organization can ensure that leadership and management strategies are common across the organization, reinforcing the vision, goals and direction.

Through a process of supervision, working practices can be viewed, human behaviours interpreted and better understood, policies evaluated in action, resource management broadened and the role of leader strengthened and developed (Ollila 2008).

Leadership of self, failure, self-efficacy and emotional intelligence

The successful critical leadership of self predisposes to broadening of skills in the leadership of others that includes colleagues, clients and the organizations in the workplace. When considering leadership it is appropriate to consider ourselves, as individuals, and the individual strategies required for managing personal development, goal achievement and failure. Success and failure are experienced by all to a greater or lesser degree throughout life’s journey, within an individual’s personal, educational and career experiences. Individuals may choose to give up after the first experience of failure and function within the comfort zone, resulting in disillusionment, dissatisfaction and dreams of early retirement. For the majority, failure can also be the determinant of future success.

Boss & Sims (2008) argue that through the process of living everyone must experience failure. Failure can manifest itself in a number of guises – it may be small and personal or large and public, exposed to scrutiny and debate. If failure is common to all, then the reaction to failure can vary depending on the individual and the personal circumstances, leading to different personal strategies:

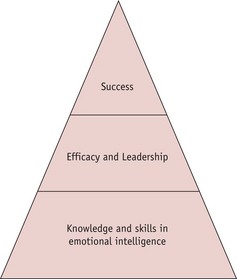

Allowing failure to affect self-esteem and confidence may lead to a downward spiral. Failure can be perceived as a stepping-stone to eventual success; the only real failure being ceasing to aspire to individual goals, and can be managed as an impetus to encourage further development and aspirations. Insight and reflection on personal and organizational failure, utilizing acquired knowledge and skills in emotional intelligence, efficacy and leadership can provide essential personal experience in the development of an effective strategy (Fig. 6.9) (Boss & Sims 2008).

Self-efficacy is an individual’s own judgement regarding how they are able to lead a situation. It is not about the skills possessed but what the individual believes they are capable of achieving. If personal judgement results in failure, then there is also doubt in self-efficacy skills (Bandura & Locke 2003, Judge et al 1997). An example to demonstrate the impact of self-efficacy may well be useful to explain its potential significance. If a midwife’s time has been spent in leading a project to its fruition whilst demonstrating effective and efficient management of allocated resource, a failure to achieve success in the project can lead to doubt regarding judgement or self-efficacy. The impact of failure can therefore affect the individual, colleagues, clients and the organization.

The ability to read an individual’s emotions can build a body of intelligence which may be utilized in the leadership strategies employed and management of resources (Salovey & Mayer 1990). Emotional intelligence demonstrates the ability to identify, express, assimilate, regulate and manipulate emotions in both self and others, whether positively or negatively (Zeidner et al 2004). With the possession of emotional intelligence, emotions can be managed. It is possible for a leader to manipulate and regulate individual and group emotion, creating either a positive or negative working environment (Salovey & Mayer 1990).

Emotional regulation and control are associated with both leadership and self-efficacy and knowledge of the human resource (Boss & Sims 2008). Emotional recognition and regulation deals with the subjective and can be difficult to measure (Goleman 1995, 1998). Goleman (1995, 1998) suggests emotion deals with thoughts which enable understanding, whilst leadership deals with cognitive skill and the organization of thought and action into measurable outcomes. Leadership is the influence individuals use to control their behaviours and thoughts in order to increase personal effectiveness and performance (Frese & Fay 2001, Sims & Manz 1996). Emotional intelligence can also be utilized as an effective facet of leadership, though the skill in managing and controlling emotion may be difficult to measure objectively and therefore must be considered sensitively.

Emotional Intelligence and the midwife leader

A midwife leader working with a team of staff in a clinical environment will, over a period of time, get to know each member of staff. Midwives working in clinical situations inevitably will demonstrate some emotional reaction in caring for women and their families. Leaders can build emotional intelligence of individual and groups of staff. This intelligence can be used positively as a management strategy; for example, a midwife who has dealt with a particularly difficult clinical situation may need a less difficult workload when next on duty. Alternatively, emotional intelligence can have a negative impact; for example, a midwife may not be asked to deal with a particular situation because of a previous emotional reaction. A number of variables can affect an individual emotional reaction in a particular situation. The midwife leader may gain emotional intelligence regarding her colleagues, but there needs to be a recognition that this intelligence is subjective and should be used with caution. However, midwifery is a caring profession where emotions may surface and effective leadership involves a degree of care and consideration of colleagues including valuing their emotional investment in the care of women and their families.

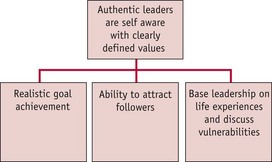

Authentic leadership

Traditional leadership theories are not sufficient to prepare future leaders for the contemporary workplace (Turner & Mavin 2007). Authentic leadership focuses upon the individual’s own life experiences, journeys and reflections rather than the application of established theoretical models of leadership (Cameron et al 2003, Lord & Brown 2004, Turner & Mavin 2007). Authentic leadership has been described as the process of owning one’s individual experiences through self-awareness and self-acceptance (Cameron et al 2003) and authentic leaders are portrayed as being self-aware with clearly defined and articulated values (Shamir & Eilam 2005). In addition, authentic leaders demonstrate a motivation towards realistic goal achievement and they possess the ability to attract followers (Fig. 6.10) (Cameron et al 2003, Luthans & Avolio 2003).

Authentic leaders can be seen as genuine in that they do not aspire to a leadership role for individual reward, but their actions are based upon their personal values and convictions (Shamir & Eilam 2005). They also recognize the areas in which they are vulnerable and are willing to share and discuss those vulnerabilities with colleagues, basing their values upon their own life experiences, and this shapes their authentic and individual leadership style (Shamir & Eilam 2005). Gardner et al (2005) consider triggers and life events to be key aspects of the development of an authentic leadership style through an understanding of self. This can comprise both positive and negative experiences which trigger changes in an individual’s self-identity (Lord & Brown 2004). Interpreting life experiences with application and adaptation of this experiential knowledge to leadership situations is part of authentic leadership (Luthans & Avolio 2003). If this application of life experience is undertaken with honesty and integrity and a clear insight into areas of vulnerability, then this leadership style can prove to be effective. Individuals therefore face different life experiences which build a body of knowledge and self-awareness. The authentic leader may present an eclectic style of leadership with a range of knowledge and skills being applied effectively in similar situations. It may be concluded that it is the application of life experience to a situation that provides authentic leadership effectiveness, not the possession of a particular set of learned skills or theoretical approach.

Kernis (2003) suggests that to behave in an authentic manner means personal values are reflected in actions. This means that actions taken by an authentic leader are not demonstrated merely to respond to another’s needs. An authentic leader does not support instant decision making or decisions that ensure personal reward and this reflects personal values based on perceptions of fairness. Therefore, the values held by an authentic leader are not necessarily those thought to be acceptable to the organization (Kernis 2003).

Reflective activity 6.1

The traditional theories of leadership imply that successful leaders do not display emotional behaviours, retaining objectivity in leadership situations (Likert 1961). Behaviourist theory recognizes the importance of employee wellbeing but this does not necessitate a leader sharing personal emotional experiences. Conversely, authentic leadership supports a leader bringing more of themselves to the workplace, which may include personal emotional experiences where these are deemed to be appropriate However, it is crucial that the authentic leader minimizes the sharing of inappropriate or potentially damaging personal emotional experiences which may compromise their position (Gardner et al 2005).

The role of leader can create negative emotional experiences, including anxiety and feelings of vulnerability and underachievement of goals (Turner & Mavin 2007). For many leaders and managers, emotional reactions to pressures of role and responsibilities are hidden beneath the surface. These hidden emotions may manifest themselves in different guises, including poor communication with colleagues, underachievement and sickness. There is a dichotomy for a leader between the control of emotions (Likert 1961) and the expression of emotions within a leadership role (Gardner et al 2005). An empirical study of senior leaders suggested that the sharing of personal life experiences through narrative stories might enable senior leaders to reflect upon their values and further develop and grow (Turner & Mavin 2007). However, these authors highlight that expression of emotion by senior leaders is restricted by personal regulation or control in order to maintain the impression of the leader not being personally exposed, thus creating personal boundaries.

Authentic leadership advocates experiential learning and development as opposed to the application of theoretical approaches where the endpoint is the goal, not the experiences gained throughout a process or journey. The sharing of an authentic leader’s life experiences predisposes to the development of values, self-awareness, fairness and motivation. However, it may be problematic to those potential leaders who wish to adopt an authentic leadership style if it is perceived personal life experiences are limited.

Reflective activity 6.2

Authentic leadership in midwifery

It is probable that authentic leadership is evident in midwifery. Midwife leaders will share a number of personal experiences with the women for whom they care and their midwifery colleagues. Many midwives have personally experienced childbirth and all have practised midwifery. Midwife leaders possess experiential learning experiences that can prove useful in leadership roles. The values, self-awareness and motivation they demonstrate are usually constructed from their own experiences. Subjectivity may be the result of personal experiences of childbirth and clinical midwifery practice; therefore, it is appropriate that both an authentic experience and knowledge of leadership theory are combined to ensure the development of a midwife leader’s objective style.

Conclusion: leadership and management within contemporary midwifery

Through supervision of midwives or promotion of midwives within an organizational structure, midwife leaders and managers have emerged at different levels of the health service. Midwives have often been appointed to leadership and management posts because they are recognized for their exceptional skills in midwifery practice. However, they may not have been adequately prepared for this leadership and management role. Some leaders and managers are effective in their role, respected by colleagues for their skills and expertise. Others may be left feeling unsupported and dissatisfied and consequently their emotions can be cascaded to their colleagues, affecting the morale of staff and subsequently the quality of care.

Midwives are ideally placed at the centre of the government’s strategy to support the agenda of change and improve the quality of contemporary maternity services. Midwives have emerged as valuable members of the multi-professional team, sharing their knowledge and expertise with and learning from fellow professionals with a shared aim to provide holistic care in a range of health and social care settings. Therefore, all midwives require knowledge and skills for leadership and management.

Reflective activity 6.3

Table 6.1 Example of a career plan template

| Career aspirations for 5 years | Goals to achieve aspirations | Professional development plan |

|---|---|---|

Women trust midwives to deliver the care they require. However, midwives can be stretched to capacity with poor strategic leadership by those with little insight into the roles and responsibilities of midwives, or the needs of women and their families. Poor strategic leadership leads invariably to poor resource management including limited financial investment to realistically sustain and develop strategy for maternity services and a national shortage of practising registered midwives.

Midwives work in a range of environments and contexts where leadership and management of resources will depend on a number of variables, including the environment, the team, the skill mix, the available budget, the workload and the nature of a project. These areas of leadership and management will affect the delivery of services to women and their families. With knowledge and insight into theories of leadership and management of resources a midwife may consider one particular leadership approach suitable to their practice or may reflect that an eclectic approach where elements of a number of approaches is applicable. The acquisition of leadership and management knowledge and skills is critical to the recognition and progression of a contemporary midwifery profession continuing to deliver expert care to women and their families.