Chapter 15 Legal frameworks for the care of the child

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

Note: Please see the website for a list of all the Acts/Statutes referred to in this chapter.

Introduction

Safeguarding children and promoting their welfare is the responsibility of every health and social care professional. An increasing emphasis is placed on outcomes, to be delivered through multi-agency working and information-sharing. Repeatedly, government documents continue to highlight the requirement for interagency and interprofessional working to safeguard and promote the wellbeing of children and young people (DCSF 2010, DH 2000a, Laming 2009). Decisions about children’s welfare and safety are complex, with high-profile deaths of children, such as Victoria Climbié and Baby P, raising criticisms and anxieties about professional decision-making, leadership and management (DH 2003a, Joint Area Review 2008). Whilst the quality of children’s services may be improving, criticisms remain of partnership arrangements, performance management, the involvement of young people in decision-making, the use of assessment to identify need and track progress, and communication to ensure the emergence of a comprehensive picture of a child’s needs (Ofsted 2009, Statham & Aldgate 2003). There are also concerns about high thresholds limiting access to services (Corby 2003, Morris 2005) and lack of compliance by local authorities with the legal rules (Preston-Shoot 2010).

This chapter seeks to enable midwives to understand the legislative framework and related policies, procedures and resources, to carry out their role effectively in working together with parents and other professionals to ensure the wellbeing and safety of children. For the definition of the child, please see Box 15.1. Please note that those working outside England and Wales need to access legislation and policy guidelines relevant to that country.

Box 15.1

Legal definition of a child

The Children Act 1989 defines a child as a person under the age of 18. In current British law, an individual has no legal entity until the moment of birth. Similarly, a person does not become a parent until his or her child is born.

The discussion below may be linked to three scenarios that may be encountered by midwives (see Case scenarios Web 15.1, 15.2 and 15.3 and a range of activities on the website suggested for learning).

The Children Act 1989

The Children Act 1989, amplified by associated regulations and statutory guidance, covers legislation relating to aspects of care, upbringing and protection of children (Braye & Preston-Shoot 2009). This includes the welfare and protection of children in disputed divorce proceedings, children in need, children at risk, children with disabilities or special educational needs, and those who need to live away from home (either short or long term) including children in hospital, boarding schools, residential homes and foster homes. These rules have been amended and supplemented by subsequent legislation, most notably the Family Law Act 1996 (to protect victims of domestic violence), the Children (Leaving Care) Act 2000 (duties regarding young people leaving care), the Adoption and Children Act 2002 (reform of adoption law and changes to the Children Act 1989 provisions, for instance concerning parental responsibility, special guardianship and advocacy), the Children Act 2004 (specifying outcomes for children and requirements for interagency working), the Children and Adoption Act 2006 (sanctions for disrupting contact between children and non-resident parents, and changes to family assistance orders), the Children and Young Persons Act 2008 (amendments to children in need and emergency protection order provisions, and changes concerning accommodated children) and the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009 (creating statutory Children’s Trusts and changes to Local Safeguarding Children Boards).

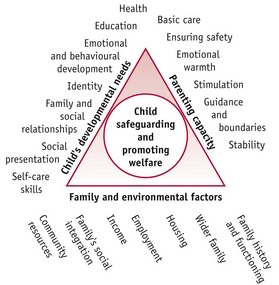

Guidance and regulations produced by central government departments provide detailed information about how legislation should be implemented. When guidance is issued under section 7, Local Authority Social Services Act 1970, it should be followed. Two published examples of these are Working together to safeguard children (DCSF 2010) and Framework for the assessment of children in need and their families (DH 2000a). These provide blueprints for agencies to work together with children (Fig. 15.1). Guidance has also been issued to clarify how outcomes for children, detailed in the Children Act 2004, should be approached (CWDC 2007, DfES 2005).

The midwife has a universal and accepted role in working with pregnant mothers, newborn babies and their parents, and is in a unique position to comment on all aspects of the health and care of newborn babies (see case scenarios and reflective activities on website). This is in direct contrast to some other professionals, for example, social workers and police, who tend to be involved with families when there is cause for concern. Whilst midwives have been involved with all children born in England (approximately 11 million), intervention by councils with social services responsibilities affects only a small proportion of families, estimated to be about 5% (DH 2007). See website and Reflective activity Web 15.2.

Key features of the Children Act 1989

The Children Act 1989 was formulated on key beliefs about children, young people, parents and the role of the State, which are given statutory recognition in the Act.

The Act is clear. The paramount duty for everyone is to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. Whilst other objectives, such as working in partnership with parents, are also highlighted, it is important to recognize that these practice principles do not overturn the paramount duty of the local authority to safeguard and promote the welfare of children (Braye & Preston-Shoot 2009, Brayne & Carr 2010, Wilson & James 2007).

Content and structure of the Children Act

Of particular interest to midwives are the parts of the 1989 Act that deal with the responsibilities of the local authority (LA) in providing support for children and families (Part III) and the protection of children (Part V).

Part 1 (section 1): Welfare of the child

The Children Act 1989 begins with a statement that the child’s welfare is the paramount issue to be taken into account in decisions made by a court in respect of children and young people (s1:1). The Act advocates avoiding delay in making decisions about a child’s upbringing (s1:2) as it can prejudice the welfare of the child. Where the court is required to take action, the Act requires it to take account of the following ‘welfare checklist’ (s1:3):

Whilst this applies to only parts of the Act and relates specifically to decisions of the court, professionals are expected to take this checklist into account when making decisions about a child.

The Act also states (s1: 5) that courts can only make an order in respect of a child if this would be better for the child than not making an order. This is based on the principle that the state should intervene in private and family life only to the degree necessary. This conforms to Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, with its principle of proportional intervention, incorporated into UK law by the Human Rights Act 1998.

Part 1 (section 2): Parents and parental responsibility

The concept of parental responsibility is described in sections 2, 3, 4 and 5. Parental responsibility is defined as: all the rights, duties, powers, responsibilities and authority, which by law a parent has in relation to the child and his property (Children Act 1989: S.3(1)).

This includes the responsibility to care for, and promote and protect the child’s moral, physical and emotional health. Although not specifically defined in the Act, this is generally considered to include decisions in respect of the name, religion and education of the child, the right to consent or not to medical treatment and adoption, to have contact and to arrange for the burial or cremation of a child.

Who has parental responsibility?

Having parental responsibility does not automatically equate with being the legal or biological parent of the child. For example, the birth mother automatically acquires parental responsibility at the moment of birth. However, the father does not have parental responsibility automatically unless he has been married to the mother. An unmarried father has parental responsibility if he is registered as the father on the child’s birth certificate (an amendment in the Adoption and Children Act 2002), or if the birth mother or a court gives him parental responsibility. Other people may also acquire parental responsibility through decisions of the court, for example grandparents, guardians, foster carers or the local authority. In these circumstances, parental responsibility can be shared amongst several people. The only circumstance in which a birth mother and married father would lose parental responsibility is when their child is adopted or a placement order is made permitting adoption to be planned. If an unmarried birth father has been given parental responsibility, it can in exceptional circumstances be removed by a court. In divorce, both parents retain parental responsibility, even if it is decided that the child should live with one of the parents.

The issue of parenting and parental responsibility is becoming increasingly complicated with the advent of surrogacy and in vitro fertilization. For example, the woman who gives birth is the legal mother and has parental responsibility. Other adults may need to adopt the child in order to become the legal parents.(see website and Reflective activity Web15.3.)

Support for children and families

The changing nature of family

Practice with children and families needs to take account of the changing nature of family life. The UK has become an increasingly multicultural society, bringing a diversity of ideas in respect of different family structures and ways of life. This diversity has been recognized within the Children Act 1989. Firstly, the Act widened the concept of people who are important to children by allowing absent parents and other relatives to be consulted and involved in decisions about the care of children, and to apply under section 8 for residence and contact orders. Secondly, for the first time in English law, the diversity and multicultural context of families have been recognized and should be taken account of and respected (s1:3). The legal rules have been changed subsequently to recognize civil partnerships, to extend to same-gender couples the right to adopt, to allow step-parents to acquire parental responsibility with the agreement of birth parents, and to create the concept of special guardianship (Adoption and Children Act 2002).

Reflective activity 15.1

Find out where your local authority children’s services department is. How has it organized its responsibilities to children?

What initiatives do you have in your area for helping vulnerable children and their families?

See if you can obtain a copy of the Children and Young People’s Plan for your area? What are the key aims and objectives for your area?

Poverty and social exclusion

Sources of stress and disadvantage for children and families include poverty and accompanying social exclusion. The Government published Ending child poverty: everybody’s business (HM Treasury 2008a), its strategy to tackle childhood poverty. In 2009, 2 million children were living in households where there was no adult in paid work, with the impact of poverty on their families being recognized as having a major effect on life chances, health, education and future employment (Hirsch 2009, Platt 2009), especially amongst black and minority ethnic group communities (Butt & Box 1998).

Employment rights

Pregnant women and their partners can access a range of benefits to help combat social inequality caused by poverty. Under the Employment Rights Act 1996, women retain employment rights whilst pregnant and should not be discriminated against. This includes paid time off for antenatal appointments, protection from unfair treatment or dismissal, the right to maternity leave, maternity pay, redundancy payment, and return to work following pregnancy (see Reflective activity Web 15.5). The Employment Act 2002 provides that every working father is entitled to paternity leave.

Family support and the Children Act

Central and local government strategies have been designed to aid vulnerable children. For example, Sure Start programmes have been targeted at children under 4 and their families within some of the most disadvantaged communities, addressing the health and wellbeing of children and families before and after birth. The aim has been to improve the health of children before entry to school to enhance their potential at school. The programmes provide access to family support, advice on nurturing, health services and early learning. Other initiatives include the concept of extended schools and the requirement on local authorities to ensure that they have sufficient children’s centres to meet local need (Apprenticeships, Skills, Children & Learning Act 2009).

The Children Act 1989 places a duty on local authorities to target particular services to children defined as being in need.

Local authorities have a general duty to:

by providing a range and level of services appropriate to those children’s needs (Children Act 1989: s.17(1)).

The definition of a child in need has been extended to include being a victim of, or witness to, domestic violence (Adoption and Children Act 2002, DH 2000b). The requirement that financial support could be given only in exceptional circumstances has been removed by the Children and Young Persons Act 2008. The aim of the duty to children in need within the Children Act is to target services to the most vulnerable, including those at risk, providing support to avoid the need for the state to seek statutory control. Service provision under section 17 may be one means by which a local authority seeks to deliver good outcomes for children and young people as defined in the Children Act 2004. However, financial constraints, reflected in high thresholds and eligibility criteria, have limited this section’s effectiveness (Morris 2005).

Family support services

Part 3 of the Children Act 1989, especially section 17 and Schedule 2, outlines the provision of services for children in need. These services may be provided by the local authority and/or the voluntary and private sector. Such services include family centres, day nurseries, fostering, childminding or playgroups, and support within the home, such as family aides (see website). The local authority may charge for these services, but any person in receipt of income support or family credit is exempt.

Children living away from home (see website)

The local authority has a duty to provide accommodation in a range of situations, including when children are in need and there is no person who has parental responsibility for them, they are lost or abandoned, or the person who has been caring for them is prevented from providing them with suitable accommodation or care. When the local authority accommodates children, they become looked after children.

Accommodation for young babies

Where there are concerns about a young baby, it is likely that the local authority would – unless there is very good reason against such – try to maintain the mother and child in their own home by provision of a family aide and/or home help. If this is not possible, efforts would be made to try to place mother and child together with foster carers who specifically work with mothers. There are still a small number of residential mother and baby homes, predominantly managed by the private and voluntary sector, which provide care, support and training for mothers with specialist needs, such as drug dependency. (For foster care and teenage pregnancy, please see website.)

Adoption (see website)

Adoption is the dissolution of parental rights and duties, which are subsequently transferred to the new adoptive parent(s).

In some cases, midwives become involved with a mother who has decided to give up her child for adoption. In rare circumstances, the mother may decide that she does not want to care for the baby after birth. If this is the case, then midwives will be involved in planning with councils with social services responsibilities or an adoption agency to manage this process.

Children with disabilities (see website)

The Children Act 1989 (section 17) recognizes children with disabilities as children first and includes them in the definition of children in need, enabling them to benefit from the same services as other children.

Midwives are at the front line of working with parents who are expecting a child with disability or where a disability is diagnosed at birth. They need to be sensitive to how information is conveyed to parents and ensure openness and honesty. In many cases, this involves referral to paediatric specialists.

An important principle in working with children with disabilities is to ensure that the views and wishes of the child are sought and not to make the assumption that this is not possible.

Disabled children are particularly vulnerable and face an increased risk of abuse in many settings. This may arise in part from social attitudes and special treatment resulting in disabled children being more isolated, more dependent, having less control over their lives and bodies, and being less able to communicate their abuse.

Female genital mutilation

The midwife may also need to be alert to the possibility of some families wishing to have the child ‘circumcised’. This might be from an awareness that the mother/family is from a culture where this practice is accepted; and if the mother herself has had this procedure. Occasionally, the mother may ask for information which might alert the midwife. Under the terms of the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2004, it is illegal to have this carried out abroad under the principle of ‘extra-territoriality’ (see website chapter 58). This is a sensitive and difficult situation, and seeking assistance from the supervisor of midwives and using the guidelines from the Department of Health (DH 2003) can be useful. Midwives must initiate their local child protection process if they feel that a female child is at risk.

The protection of children

The impact of domestic violence on children and adolescents is becoming increasingly recognized and has been well researched (DH 2000b, Hester et al 2006, Humphreys & Stanley 2006). In some circumstances, alcohol and drugs misuse and mental illness may also adversely affect parents’ abilities to care for their children (Humphreys & Stanley 2006). Women’s refuges have been established to provide a safe haven and advice for women and their children, accessed through the Samaritans, the police or social services. The legal rules have been strengthened to recognize the impact of domestic violence. The Adoption and Children Act 2002 makes a child who is a victim of, or witness to, domestic oppression, a child in need. The Family Law Act 1996 allows a court to add an exclusion order to an interim care order or emergency protection order made under the Children Act 1989, with the objective of removing the perpetrator from the family home rather than the child. If this does not prove possible, then the child may be removed using a granted emergency protection order or interim care order powers.

Along with all other professionals and voluntary sector workers involved with children, midwives have a responsibility to be alert to the possibility of child abuse and to take appropriate action where indicated. Should a midwife have any concerns about a family, she should discuss this with her senior colleagues and others who may be involved in the care of the family. This involves discussion with a supervisor of midwives, senior colleague, or doctor (Box 15.2).

Box 15.2

Adapted from DH 1997: 9–10

Responsibilities of the senior midwife

Those who manage midwifery should ensure that:

Section 47 of the Children Act 1989 places a duty on any health authority or NHS trust to help a local authority in its inquiries in cases where there is reasonable cause to suspect that a child is suffering or is likely to suffer significant harm. It is important for midwives to recognize the roles and responsibilities of other professionals in working with children and access joint multidisciplinary training in respect of assessment and child protection. Where it is agreed, following a strategy decision, that a section 47 enquiry should be instigated and the child may be at risk of significant harm, the midwife may become involved in a child protection conference. If the child is made the subject of a child protection plan, core group meetings and review conferences will follow.

Local Safeguarding Children Boards

Each health authority is required to identify a senior nurse as designated senior professional to the Local Safeguarding Children Board (LSCB). Each NHS trust must also identify a named nurse or midwife to lead on child protection matters (CWDC 2009).

The overall management of the cooperation between various agencies in respect of child protection in any local authority is the responsibility of the Local Safeguarding Children Board (Children Act 2004; Local Safeguarding Children Board Regulations 2006; Apprenticeships, Skills, Children & Learning Act 2009). Each board has a representative at a senior management level from each of the relevant agencies. They have responsibility to develop, audit and challenge local policies and procedures for interagency working and for the safeguarding and promotion of the welfare of children. They must ensure provision is made for training and raising awareness within the wider community, and for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of partner agencies, individually and collectively. They will provide regular reports to the Children’s Trust, and publish an annual report. They also conduct a serious case review of any particularly difficult cases that arise, or where a child dies as a result of abuse or neglect in their area.

Significant harm

Important in the assessment of risk is the concept of significant harm. If there is reasonable cause to suspect that a child is suffering or is likely to suffer significant harm, the local authority has a duty to make enquiries necessary to enable them to decide whether to take any action to safeguard or promote the child’s welfare (Children Act 1989: s.47). This enquiry is commonly known as a section 47 investigation.

Harm is defined in section 31(9) and (10) of the Children Act as: ‘ill treatment or impairment of health or development’.

Ill-treatment includes sexual abuse and other forms of ill-treatment that are not necessarily physical (see Box 15.3). The decision as to whether the harm is significant is measured on a comparison with the health and development reasonably expected of a similar child. It will be informed by a comprehensive assessment (DH 2000a) and take into account legal advice. Assessments should be child-centred so that the impact of parenting capacity, family and environment on the child can be clearly identified and understood (HM Government 2006).

Box 15.3

Categories of abuse and neglect

Abuse and neglect are generally considered under the following categories:

These are generally used as the basis for making children the subject of child protection plans.

Working together to safeguard children (DCSF 2010) advises that abuse or neglect is caused by inflicting harm. Whilst it is not within the remit of this chapter to provide detail of signs and symptoms of abuse, there are well-documented warning signs that may alert the midwife. Physical abuse includes hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning, scalding and suffocating. Midwives should be concerned about any bruising on a baby, particularly bruising around the face or on any soft tissues, bruising consistent with an implement being used to hit a child, finger-tip bruising or slap marks, black eyes or ears, bites, scald and burn marks anywhere on the body, or a torn frenulum. Suspicion may be raised if parents delay seeking advice about injuries or if there are discrepancies between the parents’ explanation and the actual injuries found.

Emotional abuse may be observed by the midwife in terms of poor emotional bonding and possible rejection of the pregnancy and child, unrealistic expectations and/or demands of the child, constant criticism, unequal treatment, or a child being made to feel worthless and unloved. Failing to meet a child’s basic physical or psychological needs in respect of food, clothes and safety, failing to protect the child from harm, and failing to ensure access to appropriate medical care or treatment may be examples of neglect. Failure to follow medical advice through pregnancy and postnatal care, the mental state of the mother, rough handling, and a history of drug or alcohol abuse or domestic violence also give cause for concern.

The time immediately after birth is important in establishing a positive relationship between parent and baby. Prematurity, illness of either mother or child, or other factors, sometimes hinder this relationship. The midwife is a key figure in fostering a positive relationship, recognizing what is likely to support or hinder this.

Whilst stress does not automatically lead to child abuse, it may make it more likely. Sources of stress for families include issues relating to finances, social exclusion (SEU 2001), domestic violence, mental illness of parent, and drug or alcohol abuse (Haggerty et al 2001, Hughes & Owen 2009).

Whilst acknowledging that these factors do not necessarily lead to abuse or neglect, the potential or actual impact of these on a child needs to be assessed and action taken to support the child and family as well as ensuring the child’s safety.

A midwife who is involved with a child where there is concern may be involved in a strategy discussion with other professionals to share information, determine a plan for section 47 enquiries, and consider how to immediately safeguard the child and provide interim services and support. This includes consideration of how to take race and ethnicity into account, including use of interpreters; the needs of other children; decisions about what information should be shared with the family; and the role of the police where an offence may have been committed.

Assessing children ‘in need’ and their families

The Framework for the assessment of children in need and their families (DH 2000a) and Working together to safeguard children (DCSF 2010) guidelines emphasize that promoting the welfare of children and safeguarding their needs are not separate activities. They aim to refocus attention on preventive work, together with producing a more holistic and interagency assessment focusing on strengths as well as needs (Calder 2000). Assessment begins from the point of referral and emphasizes the corporate responsibility of local authority departments, the NHS and voluntary organizations in contributing to both the assessment and the provision of services to children in need. The assessment seeks to discriminate between different types and levels of need and is crucial to improving the success of services for children. Focus on an interagency approach starts as soon as there are concerns about a child’s welfare, not just when there is concern about the child being at risk of significant harm.

The assessment framework takes account of current research to produce an approach that retains the child at the centre of three domains which interact to affect the wellbeing and development of a child within the family (Aldgate & Statham 2001). These are:

Where families fail to cooperate with an assessment, and where it remains unclear if criteria are met for application for an emergency protection order, the local authority may apply for a child assessment order which, if granted by the court, requires parents to make the child available for assessment (see Reflective activity Web 15.6).

Midwives are well placed to comment on all three assessment domains, given their close and frequent contact with newborn babies and parents; their skills in assessment, observation and communication; and their knowledge of early childhood development and needs. In visiting the home, midwives may become aware of the care, not only of newborn babies, but also of older children, lifestyles, home conditions, parenting and child abuse. Midwives can identify vulnerable children and refer them to social services for assessment, contributing to the assessment, planning and intervention as required (DH 2003b, Fraser 2003). The most common situations where midwives are involved in working with social workers in respect of children in need or at risk, are pre-birth assessments and post-birth concerns.

Making a referral

Working together to safeguard children states that anyone who believes a child to be suffering, or at risk of suffering, significant harm, should refer their concerns to children’s social care departments (DCSF 2010).

Before making a referral, the midwife should discuss concerns with a manager or a supervisor of midwives and, unless this would place the child at increased risk, discuss concerns with the family and gain their agreement for the referral. The GP should also be informed. In making the referral, it is important to be clear about the nature of the concerns and document these, referring only to known facts.

Consent and confidentiality

Personal information about children and families is subject to a duty of confidence and should not normally be shared without consent. However, the Data Protection Act 1998 permits disclosure of confidential information if it is necessary to safeguard a child. Trusts have local policies regarding this. In circumstances where there are concerns about the child being at risk or suffering significant harm, the overriding duty is to safeguard the child. Information regarding data protection is available in Information sharing: guidance for practitioners and managers (HM Treasury 2008b). This is in keeping with the Human Rights Act 1998 and Article 8 of the European Convention because the right to private and family life is a qualified right. Disclosure of otherwise confidential information is permitted providing it is done according to law and is proportional to the need identified to safeguard and promote the child’s welfare. When safe to do so, midwives should practise openly and honestly with families about child protection concerns to ensure that this relationship is not compromised and involvement with both parents and child can continue (Calder 2000).

The midwife’s role in assessment

Early identification, assessment and intervention associated with child protection cases are clearly outlined in the Common Assessment Framework for Children and Young People: a guide for practitioners (CWDC 2009). This detailed and comprehensive document outlines the role that practitioners play in the multi-agency approach to safeguarding children. The Framework is described as ‘a shared assessment and planning framework for use across all children’s services and all local areas in England. It aims to help the early identification of children and young people’s additional needs and promote coordinated service provision to meet them’ (CWDC 2009:8). All children considered at risk of significant harm must be referred directly to children’s social services or police, in keeping with Local Safeguarding Children Boards (LSCB) procedures (DCSF 2010).

Where a midwife refers a child, she should confirm this in writing within 48 hours using the Common Assessment Framework (see Box 15.4). In turn, the local authority should acknowledge the referral within one working day of receipt. The midwife may be asked to contribute to an assessment of whether a child is in need and, if so, the services which may be appropriate to promote the child’s welfare and upbringing within the family (see website). The midwife in respect of women who had been referred (see Case scenarios Web 15.1 and 15.3) would be contacted for information about previous pregnancies, attitudes towards antenatal and self-care, or home conditions, as part of the initial assessment phase, which must be concluded within 10 working days (DH 2000a).

Box 15.4

Common assessment framework

‘The situations that might lead to a common assessment include where a practitioner has observed a significant change or worrying feature in a child’s appearance, demeanour or behaviour; where a practitioner knows of a significant event in the child’s life or where there are worries about the parents or carers or home; or where the child, parent or another practitioner has requested an assessment. A common assessment might be indicated if there are parental elements (e.g. parental substance abuse/misuse, domestic violence, or parental physical or mental health issues) that might impact on the child.’

In circumstances requiring a more in-depth exploration, a core assessment is undertaken, and must be completed within 35 days (DH 2000a). Again, depending on the degree of involvement, the midwife may be invited to provide information, specialist knowledge and advice, and, in some cases, undertake specific assessments. The midwife is expected to contribute to the plan for providing support – The Child in Need Plan. However, it is important to note that it is not necessary to wait until the outcome of the assessment to begin to provide services.

Pre-birth assessment

Pre-birth assessments are undertaken when the local authority is concerned that the baby, when born, will be in need or at risk of significant harm. The safety of the child is paramount, with the pre-birth assessment evaluating the needs of the child and whether support is possible to enable the family to succeed. Assessments include consideration of parenting skills, preparation for the baby, use of medical advice and guidance, and consideration of the family and environment (DH 2000a). In these situations, the identified midwife works with social workers and other professionals in contributing to the assessment.

Particular issues that may trigger a referral to children’s social care or a pre-birth assessment are:

The unborn baby can be made the subject of a child protection plan but no further action can be taken until the child is born.

It has been held that where a local authority wishes to take early action to protect a newly born baby from potentially inadequate parents, they cannot intervene before birth. However, they can intervene immediately after the birth and base this intervention on the mother’s behaviour whilst pregnant and the presumption that this would lead to the child being at risk of significant harm (Bainham 2005).

In cases where there is serious concern about the child, they may be made subject to an emergency protection order and removed from the mother after birth. This should be planned ahead to enable removal to take place as sensitively as possible. It can be a very traumatic time for all concerned, including professionals, and it is essential that all involved are supported throughout.

The emergency protection order

Where safe for children to do so, plans to protect a child should proceed in agreement with parents; however, some cases may require emergency action. The Children Act 1989 (section 44) allows for an emergency protection order (EPO) to be made if there is reasonable cause to believe that a child is likely to suffer significant harm if:

An EPO can be made if access to a child is being denied as part of a section 47 enquiry. It gives authority to remove a child or cause the child to remain in the protection of the local authority or National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) for a maximum of 8 days. Police also have powers to remove children to suitable accommodation or to prevent their removal from hospital or safe accommodation (section 46).

In situations where parents are refusing to cooperate with section 47 but there is not sufficient concern to justify an EPO, the local authority can apply for a child assessment order (section 43). This order directs the parents or carer to cooperate with an assessment of the child.

In respect of young babies, an EPO may be applied for at birth if there are concerns that the parent will remove the child. Other examples may include a child who has been seriously injured by a parent who is refusing to allow access to the child or threatening to remove the child from hospital. In line with the best interests of the child, the Family Law Act 1996 allows for a perpetrator to be removed from the home instead of the child, through an exclusion order attached to an EPO or interim care order.

The child protection conference

The child protection conference is the first meeting at which representatives of all the agencies which have dealings with the child or the child’s family get together to share and evaluate information and consider the level of risk to a child or children. The conference decides whether the child should be made the subject of a child protection plan and makes plans for the future. Councils with social services responsibilities, or, in some areas, the NSPCC, have responsibility for calling and arranging the conference. Conferences will be led by an independent chair.

The midwife may attend a case conference to present and share information about the child and family, and will be one of many professionals in attendance. Generally, there is a manager representing each agency that attends regularly, including a representative from health, education and the police. Other professionals include social workers and their manager, local authority solicitors, paediatricians, general practitioners, health visitors, housing officers, police, teachers, foster carers, and anyone who may have a significant contribution to make to the assessment. Parents and/or carers are invited to attend but may be excluded if the independent conference chair deems their attendance would potentially jeopardize the welfare of the child (DCSF 2010, HM Government 2006). This sometimes places professionals in a situation where they feel unwilling to speak frankly in front of parents for fear of jeopardizing their relationship with them. However, it is good practice to share child protection concerns openly so parents have an opportunity to respond. (See Reflective activities Web 15.7–15.10 and 15.12.)

All discussions which take place within child protection conferences are confidential. Professionals involved in child protection have their duty of confidentiality to their client overridden by their duty to contribute to the protection of a child at risk. It is important for midwives to be adequately prepared for attendance at a conference. If you are asked to go to a case conference, you are advised to discuss this with your supervisor of midwives. Box 15.5 provides a checklist of things to consider.

Child protection plan

If a child is made the subject of a plan, a key worker is appointed. The key worker is a social worker from either the local authority or NSPCC. They have responsibility for making sure the child protection plan is developed into a more detailed interagency plan, ensuring completion of the core assessment, putting the plan into effect and monitoring it.

A core group of professionals, composed of those who have direct contact with the child, is established to develop and implement the child protection plan in conjunction with the family. Members of the core group are jointly responsible for developing, implementing and monitoring the plan. A meeting of the group should take place within 10 working days of the initial conference.

The child protection plan identifies how the child can be protected, including completion of a core assessment, short- and long-term aims to reduce risk to the child and promote the child’s welfare, clarity about who will do what and when, and ways of monitoring progress.

If the child is made the subject of a child protection plan, this certainly does not mean that all other work with the child and family ceases. They may also still be eligible to be considered as children ‘in need’ for whom a range of services may be provided.

Conclusion

The Children Act 1989, together with subsequent legislation, protects the rights of children, promoting their status within society. Midwives must be aware of the implications of the Act and apply them to their practice. Midwives are uniquely situated to identify risk factors and act as advocates for newborn babies and other children during their professional practice. Detailed and contemporaneous records should be maintained throughout, as these may be required in assessments and child protection conferences (NMC 2008). Key amendments are constantly made to the Children Act and so it is important to keep up to date and access relevant websites and support organizations so that knowledge is current. Using the three case scenarios identified at the beginning of this chapter (available on the website) will have helped you explore aspects of child care law in relation to midwifery practice, through exploration of supporting concepts, on-line materials, and professional and statutory documents. In all cases, it is important that the midwife liaises with the supervisor of midwives and with other professionals, thus perpetuating a multi-agency approach to child support.