Chapter 22 Physical preparation for childbirth and beyond, and the role of physiotherapy

After reading this chapter and practising the suggested activities, you will:

Introduction

This chapter aims to equip midwifery students and midwives with the knowledge and skills required to understand issues such as exercise, good posture, relaxation techniques and effective physical preparation for pregnancy and childbirth, plus common musculoskeletal dysfunctions in pregnancy and childbirth. This will enable them to advise and support women in their care and recognize situations when referral to another professional is indicated. The author is a women’s health physiotherapist and will refer to the role throughout, with further information on the specialty towards the end of the chapter.

Exercise and sport during pregnancy

Pregnancy is a time when women are often receptive to health education messages. This can include the introduction of exercise as not just having short-term benefits during the pregnancy and childbirth period, but also holding long-term health gains. There is evidence that exercise during pregnancy can benefit both the woman and fetus (RCOG 2006a) and is harmful to neither, provided the pregnant woman is progressing normally and healthily (Artal et al 2003). Therefore it is suggested that women should be encouraged to start, or continue with, appropriate exercise to derive the associated health benefits (NICE 2008, NICE 2010, RCOG 2006a). These include a reduction in fatigue, varicosities and peripheral swelling; a lower incidence of insomnia, stress, anxiety and depression; and, possibly, weight-bearing exercise in pregnancy may result in a shorter labour and a decrease in delivery-related complications (RCOG 2006a). In addition, a randomized study of women with gestational diabetes (Bung et al 1991) found that more than three-quarters of those following an exercise programme demonstrated improved glucose tolerance, so exercise is recommended for this group (RCOG 2006b). There is no robust evidence that exercise will prevent the onset of gestational diabetes in women (Artal & Sherman 1999).

It has been suggested that babies born to exercising women may tolerate labour better and be less likely to demonstrate signs of stress, such as meconium (RCOG 2006a).

There appears to be some variation between what are considered absolute or relative contraindications to (aerobic) exercise in pregnancy (ACOG 2002) and conditions requiring medical supervision while undertaking exercise in pregnancy (RCOG 2006a). Guidance produced by physiotherapists (ACPWH 2004) suggests the contraindications and precautions indicated in Table 22.1.

Table 22.1 Absolute contraindications and precautions to exercise in pregnancy*

| Absolute contraindication | Precaution |

|---|---|

| Serious cardiovascular, respiratory, renal or thyroid disease | Asthma |

| Poorly controlled type 1 diabetes | Diabetes type 1 if insulin regimens are well controlled and exercise is moderate – discuss with diabetic consultant, nurse or GP |

| Risk of, or current, premature labour | History of miscarriage |

| Cervical incompetence | Vaginal bleeding |

| History or risk of intrauterine growth retardation and premature labour – reduce activity after 12 weeks | Reduced fetal movement |

| Hypertension – should be discussed with the woman’s doctor | Pre-pregnancy hypertension |

| Placenta praevia after 26 weeks’ gestation – should be discussed with the woman’s doctor | Placenta praevia |

| Vaginal bleeding | |

| Hypertension – should be discussed with the woman’s doctor | Pre-pregnancy hypertension |

| Severe rhesus isoimmunisation | |

| Sudden swelling of ankles, hands or face | Anaemia |

| Acute infectious disease | |

| Extreme obesity | |

| Breech presentation | |

| Extreme underweight (BMI <12) | |

| Heavy smoking | |

| Thyroid disease |

* Adapted from ACPWH 2004.

The aim of exercise during pregnancy should be to maintain or moderately improve fitness levels (ACPWH 2004) without trying to reach peak fitness or train for competition (RCOG 2006a). It is impossible to go into any detail of different regimens within the constraints of this chapter, but the needs of different women will vary, based on whether they were a complete non-exerciser, non-regular exerciser, regular exerciser or elite athlete before conception (ACPWH 2004). Women should be advised to monitor their level of effort during exercise, to ensure that they are not overexerting themselves, and if using a gym, should seek advice from professional staff.

Commonly described tools are the talk test, Borg’s scale of perceived exertion, and heart rate (RCOG 2006a):

Women should avoid overheating during exercise, as a maternal core temperature over 39.2°C might be teratogenic in the first trimester (RCOG 2006a). They can minimize this risk by drinking sufficient fluids during exercise, and avoiding exercise in very hot conditions. Women must also know when to stop exercising, and seek a medical opinion. This includes onset of symptoms such as dizziness, faintness or headache; shortness of breath before exertion or breathlessness during exercise; any pain, e.g. abdomen, pelvic girdle; painful uterine contractions; decreased fetal movements; vaginal loss, urinary incontinence, ruptured membranes; swollen leg(s); muscle weakness (RCOG 2006b).

Regular exercisers familiar with a particular activity or sport, such as walking, aerobics, swimming or dancing, can usually continue with it.

Those unaccustomed to exercise should be advised to start with 15 minutes of continuous exercise three times a week, gradually increasing to 30-minute sessions four times a week or daily (RCOG 2006a). Exercise in water, often referred to as aquanatal exercise, may offer a feeling of weightlessness, and reduced jarring of the joints, possibly offering some relief from aches and pains, an increase in energy and better sleeping (Brook et al 2008).

Scuba diving is contraindicated during pregnancy as the fetus is not protected against decompression sickness and gas embolism, and women should be warned that contact sports and pursuits which might result in a fall, such as horse riding, could result in fetal trauma (ACPWH 2004, RCOG 2006a).

Readers are advised to access appropriate sources – for example, ACPWH 2004, RCOG 2006a and 2006b – for further and updated evidence-based information, before discussing recreational exercise with pregnant women in their care.

Reflective activity 22.1

What exercise groups are available specifically for pregnant or postnatal women in your area? If possible, ask to attend one, or check whether any women you know have attended them, and assess their value. Record this information for future reference.

Muscle groups

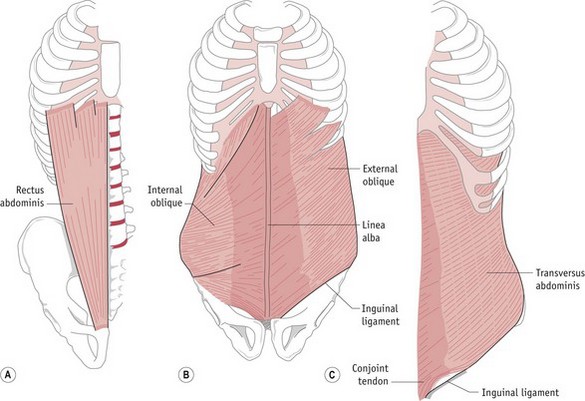

Two muscle groups that are affected more than others by pregnancy and childbirth because of their position, structure and function are those of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall. The pelvic floor is described and illustrated elsewhere within this book, but it is also useful to understand the structure and function of the abdominal muscles (Fig. 22.1).

Figure 22.1 Muscles of the abdominal wall. A. Right rectus abdominis. B. Right internal oblique and left external oblique muscles. C. Left transversus abdominis.

(Palastanga et al 2006, reproduced with permission)

The abdominal muscles have various roles, including protection and support for the abdominal contents. More specifically, their main functions are flexion of the lumbar spine (recti abdominis), side flexion and rotation of the spine (external and internal obliques) and postural support (transversus abdominis, working with the pelvic floor muscles) (Brook et al 2008). As pregnancy progresses, the abdominal muscles are stretched considerably by the gravid uterus, causing recti abdominis to become longer, wider and thinner (Y Coldron, unpublished PhD thesis, 2006). In addition, the linea alba (an area of connective tissue in the midline) may become wider and thinner (divarication) or even split (diastasis). Although there is little information on the effect of pregnancy on transversus abdominis (Brook et al 2008), its role along with the pelvic floor muscles – that is, support for the intra-abdominal organs, lower spine and pelvic girdle joints – is significant.

Many women’s health physiotherapists will include pelvic floor muscle and transversus abdominis exercises in any advice they give to pregnant women, whether it is in a parent education session, exercise class, or during individual assessment of a musculoskeletal problem. Midwives may wish to do the same.

Pelvic floor muscle exercises

There is evidence that pelvic floor muscle exercises during pregnancy can prevent urinary incontinence (Mørkved et al 2003) and reduce the likelihood of prolonged second stage labour (Salvesen & Mørkved 2004). The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has suggested that pelvic floor muscle training should be offered to women in their first pregnancy as a preventive strategy for urinary incontinence (NICE 2006a).

In non-pregnant women, research has suggested that a sizeable minority of women given verbal instructions on pelvic floor muscle exercises will not perform an optimum contraction (Bump et al 1991) and recent advice on the management of urinary incontinence suggests that a digital assessment of the muscles should be undertaken prior to commencing a course of exercises (NICE 2006a). Physiotherapists have been advised against such examination on pregnant women if there is a history of miscarriage or the woman has been advised to avoid sexual intercourse whilst pregnant (CSP 2003). Also, vaginal examination would not be practical in many situations when a pregnant woman is being advised on pelvic floor muscle exercises, e.g. parent education session, or exercise classes. Therefore, it is important that physiotherapists, midwives and any other health professionals teaching pelvic floor muscle exercises give clear instructions. There are many different ways to do this, including:

‘Imagine you are trying to stop yourself breaking wind, and at the same time trying to stop your flow of urine midstream’ (Brook et al 2008); the ‘lift’ analogy, i.e. closing the doors (a squeeze) and moving upstairs (a lift); the action of a vacuum cleaner (Bø & Mørkved 2007).

If women are not sure that they are contracting correctly, they could look at the perineum using a hand mirror, and see if the area lifts away from the mirror as they squeeze. Alternatively, they could try to stop the dribble at the end of voiding but should not stop midstream as this may disturb normal neurological activity (Bø & Mørkved 2007) and affect emptying.

Advice on how often to exercise and how many squeezes to undertake varies from author to author but a recent review of evidence suggests building up to 8–12 near-maximum contractions three times a day. In addition, any women experiencing stress or urge urinary incontinence should also squeeze before and during those activities which make them leak, e.g. cough, sneeze, on their way to the toilet (Bø 2007). A study of 23 pregnant women complaining of stress urinary incontinence (Miller et al 2008) showed they could reduce leakage by undertaking this anticipatory contraction, often referred to as ‘the Knack’.

Transversus abdominis exercises

Although many women have heard of pelvic floor muscles, far fewer will be aware of transversus abdominis, although this may change owing to recent interest in gym ball exercise and Pilates, which focus on core stability. Professionals may prefer to use a lay term such as ‘deep’ or ‘support’ muscle.

As the muscle lies under other layers, it is difficult to feel or see, so, as with pelvic floor muscle exercises, clear instructions are necessary. One description is:

‘Place your hand on the lower part of your tummy under your bump. Breathe in through your nose. As you breathe out, gently draw in your lower tummy away from your hand towards your back, then relax’ (ACPWH 2001).

As with pelvic floor muscle exercises, a review of the literature regarding exercise and pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (Vleeming et al 2008) suggests that researchers use a range of exercise regimens, but the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Women’s Health (ACPWH) suggests a contraction lasting up to 10 seconds, with up to 10 repetitions, repeated six to eight times per day (ACPWH 2001).

Low back and pelvic girdle pain

Many women experience lower back or pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy. Low back pain normally refers to pain of (lumbar) spinal origin, while pelvic girdle pain (PGP) originates in the symphysis pubis or sacroiliac joints (Brook et al 2008). Different authors report great variations in incidence, from 4% to 76.4%, largely due to wide methodological differences, but there is strong evidence to suggest 20% is accurate for PGP (Vleeming et al 2008). There are many factors that make pregnant women prone to low back pain or PGP, including fatigue, increased joint mobility related to hormonally induced changes in collagen, pressure on pain-sensitive structures by remodelled collagen, weight gain with an associated change in posture, and pressure from the growing fetus (Barton 2004a). Specific risk factors are probably a history of previous low back pain or trauma to the pelvis (Vleeming et al 2008) but in many cases no reason is identified (ACPWH 2007a). Common signs and symptoms include pain, difficulty walking (a waddling gait), clicking or grinding in the anterior or posterior pelvic joints, and difficulty with activities such as housework and sexual intercourse (ACPWH 2007a). Pain may occur in one or more of a variety of sites around the lower back, posterior or anterior pelvis, hips and groins, and common triggers include standing on one leg (e.g. climbing stairs, dressing) and straddling movements (e.g. getting in and out of the bath, turning in bed) (ACPWH 2007a). Evidence-based guidance for the management of pregnancy-related PGP recommends exercise in pregnancy, specific stabilizing exercises postnatally, physiotherapy, a pelvic belt for short periods, acupuncture, and appropriate analgesia (Vleeming et al 2008). Current guidance on the management of backache during pregnancy (NICE 2008) suggests women should be advised that exercising in water, massage therapy, and group or individual back care classes might help to ease their symptoms.

Midwives are often the first health professional with whom pregnant women will discuss any PGP, and having excluded any other possible cause of the symptoms, such as urinary tract infection, Braxton Hicks contractions, or labour, the midwife needs to explain the condition, advise on analgesia and offer general advice such as that in Table 22.2 (ACPWH 2007a).

Table 22.2 General advice for women experiencing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain*

| Advice | It can help to: |

|---|---|

| Remain active within the limits of pain | Avoid activities which she knows make the pain worse |

| Accept offers of help and involve partner, family and friends in daily chores | Ask for other help if needed |

| Rest is important | Rest more frequently, or sit down for activities that normally involve standing, e.g. ironing |

| Avoid standing on one leg | Dress sitting down |

| Consider alternative sleeping position | Lie on her side with pillows between legs for comfort. Turn ‘under’ when turning in bed, or turn over with knees together and squeeze buttocks |

| Explore alternative ways to climb stairs | Go upstairs one leg at a time with the more pain-free leg first and the other leg joining it on the step |

| Plan the day | Bring everything needed downstairs in the morning and set up changing stations both up and downstairs. Have drinks on hand, e.g. thermos flasks. A rucksack may be helpful to carry things around the house, especially if crutches have to be used |

| Avoid activities that involve asymmetrical positions of the pelvis | Avoid sitting cross-legged. Avoid reaching, pushing or pulling to one side. Avoid bending and twisting to lift or carrying anything on one hip, e.g. toddlers |

| Consider alternative positions for sexual intercourse | Try lying on the side or kneeling on all fours |

| Organize hospital appointments for the same day if possible | Combine appointments for antenatal care and physiotherapy |

* ACPWH 2007a, reproduced with permission.

Although rare, osteoporosis can occur during pregnancy, most commonly affecting the vertebrae, ribs and pubis (Barton 2004a). Symptoms such as backache and groin pain may make it difficult to differentiate it from other musculoskeletal dysfunctions. It should be considered, particularly if women are subject to other risk factors, such as long-term use of corticosteroids, thyroid problems, malabsorption disorders (e.g. coeliac disease), smoking, poor diet or low bodyweight (Carne 2008).

Posture and moving and handling

As every pregnant woman is affected by hormonal changes and, to varying degrees, postural adaptations to accommodate the developing fetus, then all are at risk of the various musculoskeletal dysfunctions discussed. Consequently, every pregnant woman should be offered appropriate advice to minimize the chance of such problems developing. Although such advice might not be as specific as that shown in Table 22.2, it could include advice on posture in standing (Fig. 22.2A), sitting (Fig. 22.2B) and lying (Fig. 22.2C), movement on and off a bed (Fig. 22.2D) and lifting (Fig. 22.2E) (Barton 2004a).

Figure 22.2 A. Good posture in standing. B. Good sitting posture. C. Example of a comfortable sleeping position. D. How to get on and off the bed. E. Good lifting technique.

(ACPWH 2001, reproduced with permission.)

The midwife can assist women in understanding the importance of posture, and clarifying good back care. This includes getting up from the examination couch, which, if the woman sits up from a lying position, imitates performing a sit-up and puts great strain on the abdominals as well as the back. Encouraging the woman to move to a side-lying position and then swing her legs down whilst pushing herself up with her arm, and suggesting that she does this at home when getting in and out of bed, can be of great help.

Referral to physiotherapy

If there is a women’s health physiotherapy service available locally, the midwife, obstetrician or general practitioner should be able to request assessment and treatment. In some places, pregnant women may be able to self-refer. When and to whom to refer may also depend on local protocol, the confidence and experience of the midwife concerned, and the physiotherapy service available (see later section on women’s health physiotherapy). For example, some physiotherapists might offer advice or exercise groups for pregnant women, whilst others may only accept referrals for women with a specific musculoskeletal dysfunction that has not responded to advice from the midwife or doctor.

Relaxation

The use of relaxation in pregnancy and labour goes back to the mid-20th century, if not before. Grantly Dick-Read referred to relaxation as ‘a condition in which the muscle tone throughout the body is reduced to a minimum’ (Dick-Read 1954), while physiotherapist Helen Heardman preferred ‘reduction to a minimum of mental and muscular energy conducive with life’ (Heardman 1959). It has been suggested that relaxation and breathing awareness during labour may help address the pain–anxiety–tension cycle, act as a distraction technique, increase tolerance of pain, and offer a coping strategy (Schott & Priest 2002). Studies of parent education sessions indicate that some women might be made more aware of pain relief techniques rather than improving their own ability to cope with pain (Fabian et al 2005). Simple ‘sighing-out-slowly breathing’ is more likely to be used than a relaxation technique taught in classes (Spiby et al 1999). A systematic review of randomized controlled studies of complementary and alternative therapies for labour pain, including breathing (respiratory autogenic training), hypnosis and massage, found no proof of efficacy (Huntley et al 2004).

However, despite the lack of evidence to support their effectiveness, midwives are still advised to support women’s use of breathing and relaxation techniques and massage they have chosen to use in labour (NICE 2007). In addition, relaxation may be considered a useful ‘life skill’ for dealing with stress caused by changes in lifestyle (Fordyce 2004) and – of particular relevance to expectant and new mothers – coping with the stresses of pregnancy (Brayshaw 2003), a crying baby or rebellious toddler (Schott & Priest 2002).

Health professionals teaching relaxation should ideally understand and believe in what they are teaching, and have practised the techniques before introducing them into their practice (Schott & Priest 2002). There are many different techniques, but physiological relaxation devised by Laura Mitchell is taught widely by physiotherapists and midwives (Brayshaw 2003). The method is based on the physiological concept of reciprocal relaxation – i.e. if one group of muscles is tightened, then the opposite group will relax. People who are stressed or tense adopt a typical posture, e.g. fists clenched, shoulders hunched. The Mitchell technique addresses tension in different parts of the body with a set of instructions for each joint:

Physiological relaxation can be practised in any suitable, comfortable position, using the instructions in Box 22.1. Eventually, the participant should be able to memorize the instructions in bold, and use the technique whenever required, and for a range of life situations that might cause stress.

Box 22.1

Physiological relaxation*

Reflective activity 22.4

Practise the relaxation technique in Box 22.1 yourself a few times. When you are familiar with it, try it out when you feel tense or stressed. This will help with your teaching of the technique, and how you explain the effect.

Postnatal exercise and advice

Postnatal exercises target the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles as the groups most affected by pregnancy and birth, and are designed to aid a return to previous fitness levels (ACPWH 2010). Transversus abdominis and pelvic floor muscle exercises may be taught as they were during pregnancy (see above) and women reminded that these exercises can be practised in a variety of positions, so can be undertaken whenever and wherever they are remembered.

Whereas previous generations of new mothers might rest at home or in hospital for a period of days or even weeks before expecting to return to ‘normal’ activities, current expectations are for a much speedier recovery (Barton 2004b). It is, therefore, pertinent to encourage appropriate, safe exercises as soon as possible to help return the soft tissues to their pre-pregnancy condition and minimize the risk of musculoskeletal problems. Current guidance (ACPWH 2010) gives no specific time at which to start, just suggesting as soon as possible, but a woman’s choice may be influenced by any pre-existing or de novo musculoskeletal dysfunction, labour, or delivery. In a study of 1193 women Thompson et al (2002) found that primiparous women and those who had undergone an assisted vaginal delivery reported more perineal pain than others, whilst those who had undergone caesarean section reported a higher incidence of exhaustion and bowel problems. In the absence of evidence that early, appropriate exercise is detrimental to such women, midwives can encourage it. It is suggested (Barton 2004b) that the pumping action of pelvic floor exercises assists venous and lymphatic drainage, removing traumatic exudate, so reducing symptoms.

If a woman has experienced a stillbirth or neonatal death, exercise and a return to normal physical activity may be a low personal priority. However, written advice, which can be consulted when the time is right, is a useful resource (ACPWH 2007c).

Women are advised to avoid stronger abdominal exercises until they have good transversus abdominis control, especially if a significant divarication or diastasis – over three fingers’ width – persists (Brook et al 2008). This can be checked by a physiotherapist or midwife by asking the woman to lie flat on her back (one or no pillows), with her knees bent and feet flat on the bed. The fingers of one hand are placed widthways on her abdomen, just above or below the umbilicus. As the woman is asked to lift her head and shoulders and reach down towards her feet, it is possible to feel the recti abdominis muscle bellies pressing against the fingers, and you can then gauge the gap in finger widths (Barton 2004b).

Reflective activity 22.5

Check recti abdominis on a friend, family member or colleague who has had children. Compare to a nulliparous woman. Are you confident in what you are doing and feeling? Could you ask a more experienced midwife or women’s health physiotherapist for guidance?

There are no published studies which suggest that a rapid return to exercise or sport would, in the absence of medical complications, prove detrimental, but advice is that exercise regimens should be resumed gradually, be individualized (Artal et al 2003), not resuming high impact activity too soon (RCOG 2006a). Advice from a midwife or physiotherapist can include brisk walking, or swimming when there has been no vaginal bleeding or discharge for 7 consecutive days (ACPWH 2010).

Some maternity units will have no or limited inpatient postnatal physiotherapy input. In the latter case, physiotherapists may restrict their service to women with postnatal complications, such as ongoing or delivery-related musculoskeletal dysfunctions, third or fourth degree tears, postnatal urinary retention, or rectus abdominis divarication or diastasis. Although guidance on postnatal care (NICE 2006b) suggests that backache should be managed as in the general population, European guidelines on the management of pelvic girdle pain (Vleeming et al 2008) recommend specific stabilizing exercises postnatally.

Women’s health physiotherapy

Physiotherapists in the UK have a long history of advising and treating women during pregnancy and the postnatal period (see website). The ACPWH promotes the role of the physiotherapist in women’s health; improvement of knowledge and skills and informing members of relevant professional and political developments. It fosters mutual understanding and provides opportunities for inter-professional learning in order to facilitate good working relationships between members of the healthcare team and their professional bodies, and to promote all relevant aspects of health education and patient care (ACPWH 2008).

The role of women’s health physiotherapists in the UK is diverse, usually including the care of women antenatally and postnatally, and often involvement in parent education sessions. Clinicians may be specialists in the treatment of pregnancy-related musculoskeletal dysfunctions (ACPWH 2008). Many treat incontinence (both female and male) and other pelvic floor muscle dysfunctions, and may care for women undergoing gynaecological surgery. In addition, other areas of practice might include neonatal paediatrics, osteoporosis, menopause, breast care, and lymphoedema management (Brook 2007).

The Department of Health has proposed that there is a place for physiotherapy in the multi-professional team offering antenatal care (DH 2004), and that care from a range of maternity professionals including midwives, obstetricians and other specialists should be available (DH 2007). Physiotherapists are the experts in musculoskeletal assessment (Barton 2004a), and current evidence-based guidance on the management of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (Vleeming et al 2008) recommends exercises in pregnancy; an individualized treatment programme focusing on specific stabilizing exercises as part of a multifactorial treatment for the condition postnatally; individualized physical therapy; manipulation or joint mobilization as a possible test for symptomatic relief; acupuncture; and possibly the trial of a pelvic belt for symptomatic relief. Most, if not all, of the above are within the scope of practice of many physiotherapists working within women’s health and are not commonly practised by other professionals working within maternity services.

Unfortunately, there appears to be little or no consistency of provision of women’s health physiotherapy around the UK (Brook 2007). This is a disadvantage to other professionals, such as midwives, who may or may not have access to such specialist services. It is reported (Brook 2007) that a unit handling 6000 deliveries a year might have anything between the equivalent of one and four full-time physiotherapists offering a range of women’s health services. The last 20 years has seen a large increase in their role within continence services with a decrease in obstetric work, possibly related to a lack of appropriate research in the specialty (Mantle 2004).

Conclusion

Midwives are the prime care providers and advisors for women during their childbearing year. As continuity of care is recommended (NICE 2008) it is ideal if midwives are knowledgeable and competent to offer advice on posture and exercise in pregnancy and the management of musculoskeletal dysfunctions, as well as a return to normal activities postnatally. They must also know what additional services are available locally, including those offered by women’s health physiotherapists, so that safe, high-quality maternity care is available for all women and their partners (DH 2007). This period is an ideal time to provide advice on posture, exercise and moving and handling that women can go on to use during their early parenthood and beyond.