Chapter 27 Fertility and its control

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

The control of fertility does not just involve the use of contraceptive techniques but is also a political issue with governments worldwide regulating access to various forms of contraception and abortion. The health of women and their families is linked to being able to control their fertility and, therefore, midwives and other health professionals have an important contribution to make toward the reproductive and sexual health of women.

Worldwide, 1 in 5 pregnancies end in abortion. In England and Wales in 2006 the abortion rate rose to 18.3 per 1000 women aged 15 to 44, with rates varying from 3.9 for the under 16 years to 35 for 19-year-olds (DH 2007). Britain has one of the highest rates for teenage pregnancies in Europe, with 90,000 teenagers becoming pregnant every year, 8000 being under 16 years old. The Government teenage pregnancy strategy has aimed to halve this number by 2010 (Social Exclusion Unit 1999), though indications suggest that this target will not be achieved.

Having an unplanned pregnancy can be a traumatic experience for the woman and her partner and it is therefore important that both have access to information about contraception and the services available to them. This chapter will cover details of the different contraceptive methods and also the midwife’s contribution to the contraceptive and sexual care of the mother.

Family planning services and contraceptives are provided free under the UK National Health Service. A couple or an individual requiring family planning advice and supplies may go either to their general practitioner or to a community family planning clinic. In some areas there is also a domiciliary service for selected clients who, for some reason, do not attend the clinics. A variety of clinics may be provided including ‘drop-in’ clinics for young people as well as the more traditional sessions. Some clinics also specialize in specific areas such as psychosexual counselling.

Resuming relationships following childbearing

Women vary in their approach to resuming marital relations after childbirth and it is common for newly delivered mothers to feel extremely tired and also guilty about their reluctance to have sexual intercourse. For the man, the effects of witnessing a delivery can be a highly emotional experience and may result in tension or guilt (Clement 1998), but problems of changed sexual relationships are often regarded as the fault of the woman. The man may feel rejected when the baby is establishing a relationship with its mother, and mothers experiencing postnatal depression may find their satisfaction with the relationship with their partner is reduced. This, in turn, may increase the man’s guilt and frustration. Women have far better opportunities than men for obtaining advice on these intimate matters, so it is important that the midwife takes the time to provide opportunities for counselling or, where necessary, referral to specialist counsellors.

Methods of contraception

The ideal method

The ideal method should be an effective, acceptable, simple, painless method or procedure which does not rely on the user’s memory:

Male contraception

Coitus interruptus (withdrawal method)

This is a method which is used by a large number of couples at some stage in their relationship. It depends on the man withdrawing his penis from the vagina before ejaculation takes place and thus requires control. This may be acceptable to some couples but may cause considerable frustration and stress in others.

Because of the risk of leakage of seminal fluid before withdrawal, coitus interruptus is not considered a very safe method. If no other alternative is acceptable, the use of a spermicide pessary or foam would reduce the risk of conception by helping to destroy any sperm released into the vagina before withdrawal.

Condom or sheath

The condom or sheath is probably the most widely used contraception in the first few months after childbirth. As a barrier method, it not only provides protection against conception but also is effective in preventing the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV (Everett 2004). For this reason, many couples use this in addition to other methods and the regular use of condoms should be encouraged as part of the promotion of safer sex. Condoms, however, cannot protect against local infestations such as scabies and lice. Because of the strong links between specific types of the human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer (Guillebaud 2007), it is reasonable to assume that condoms may reduce the risk of cervical neoplasm.

In the UK, condoms can be obtained free from family planning clinics and Department of Sexual Health clinics, or purchased at chemists or other retail outlets, with a wide variety of sizes, textures and flavours being available. Condoms should no longer be used if lubricated with spermicide, as this is thought to increase the risk of HIV transmission (Guillebaud 2007). Most condoms are made from latex. Occasionally, men and women report sensitivity to the latex, and condoms made from a hypoallergenic latex can be tried. Rarely, an allergy to the latex occurs; the Avanti condom, which is made from polyurethane, can be used in these situations. A new condom, called Ez.on, is also made from polyurethane and is slightly different in shape to conventional ones, with a tight base but a looser-fitting shaft, thus theoretically making it less likely to break and allowing more sensation for the man.

The midwife should never assume that either partner knows how to use condoms correctly and safely, and if necessary she should be prepared to explain the correct method for using a condom. The golden rules for safe use of condoms include:

Following use, in the event of damage or spilling of seminal fluid, unless another contraceptive is already being used, the woman should seek advice from her GP or family planning clinic regarding the need for emergency contraception. The condom has a failure rate of 2–12%.

Future developments

Male hormonal contraception is presently under research. Current trials are mainly using progestogens that inhibit production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), thus reducing sperm production, with testosterone replacement needed to prevent side-effects. Other trials are using androgen, which induces sperm suppression (Herdiman et al 2006). The aim is to prevent sperm production whilst having no effect on ejaculation. Apart from the effectiveness of this type of contraception, there is the issue of whether women would be happy to rely on their male partner for contraception of this type.

Female contraception

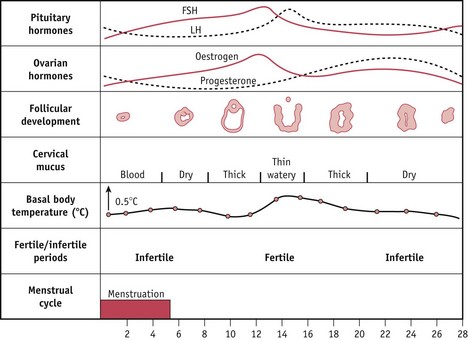

Physiological methods (Fig. 27.1)

For some people, this is the only acceptable method of contraception. The ‘safe period’ refers to the time during the menstrual cycle when conception is less likely to take place. It is known that ovulation occurs approximately 14 days before the onset of the next menstrual period and that fertilization is possible up to 5 days before and 2 days afterwards. Allowing an extra day either end, intercourse should be avoided for these 10 or 11 days during the cycle.

Theoretically, this is very easy; however, in practice, to determine the exact time of ovulation takes time and patience. It will also depend upon the regularity of the woman’s menstrual cycle. The physiological return of ovulation following childbirth is variable and difficult to assess, making this method very unreliable in the first few months after childbirth. Various methods have been developed to allow the ‘safe period’ to be worked out.

The standard days method (SDM)

This is based on the abstinence from unprotected sexual intercourse on days 8–19 of every cycle, assuming the woman has a regular cycle of 26–32 days.

The 2 day method

This is based on the presence of cervical secretions seen by the woman. Fertility is assumed when any secretions are present and also the following day.

Both the SDM and the 2 day method have the advantage of being simpler than the traditional calendar, temperature and Billings methods. However, any woman wanting to use these must be advised to seek expert help in order to determine their suitability and ensure correct explanation of the techniques. Both methods have shown good efficacy in women with regular cycles.

Lactational amenorrhoea method (LAM)

This is a fairly efficient method which can be used in the fully breast feeding mother in the first 6 months postpartum, providing certain criteria are met:

If any of the criteria change, the mother is potentially fertile. It is estimated that this method has a failure rate of 2% (Guillebaud 2007).

Persona

Persona combines the features of a micro-laboratory and a microcomputer and is designed to enable calculation of the potentially fertile and unfertile parts of the cycle. The device measures levels of LH and oestrogen breakdown products (E-3-G), by testing the urine with a dipstick that inserts into the machine. The device calculates the likely date of ovulation well in advance, and allowing for sperm survival time, the woman is then shown ‘green’ days when conception is unlikely and ‘red’ days when conception could occur. To provide the machine with sufficient information for these calculations, a minimum of 16 tests in the woman’s first cycle and eight in subsequent cycles are required. Persona can only be used if the cycles are within 23–35 days in length.

Persona may be of limited value following childbirth, as it requires the woman to have two successive cycles of 23–35 days and this makes it inappropriate for use in breastfeeding mothers. With perfect use, the failure rate of Persona as a contraceptive tool is 6 per 100 woman years; however, for the typical user the rate is higher (Guillebaud 2007). Persona can be used for planning a pregnancy but there are few references to the efficacy of Persona used for this purpose.

Barrier methods

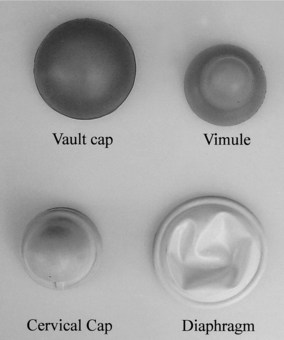

Occlusive caps

These devices cover the cervix and mechanically obstruct the entrance of spermatozoa.

They are made in a variety of sizes and must be fitted individually. Caps are checked for fit at regular intervals, especially after childbirth or loss or gain of weight. With correct and conscientious use, the rate of pregnancy can be as low as 2 per 100 woman years, but a more typical rate would be 5–10 per 100 women years (Guillebaud 2007). Cervical caps are less effective as a contraceptive in multiparous women.

The diaphragm or Dutch cap

This is one of the oldest methods of female contraception and has changed very little in design. A postnatal mother who wishes to use a diaphragm should not be fitted until 6–8 weeks postnatally, to allow the uterus and cervix to return to a non-pregnant size and the vaginal muscles to regain their tone. The shallow rubber diaphragm has a circular spring around the perimeter, allowing it to be compressed and inserted into the vagina rather like a tampon, with the diaphragm lying between the posterior fornix of the vagina posteriorly and the suprapubic ridge anteriorly (Fig. 27.2). The diaphragms come in graduated sizes and must be fitted individually.

A woman who has used a diaphragm before may require a larger size after childbirth and this may need adjustment as the vaginal muscle tone improves. A diaphragm that is too large protrudes and causes discomfort, or may produce extra pressure, giving rise to urethritis-type discomfort; however, if too small, it will move around and will not provide protection. A well-fitting diaphragm is unobtrusive and will not be noticed during intercourse. It should remain in situ for 6 hours after intercourse and is then removed at a convenient time. Failure rates vary from 4% to 18%, depending on the care and consistency of the woman.

Other caps (Fig. 27.3)

Other types of cap less commonly used may be very useful in particular cases. They all rely on suction to remain in place. The use of lubricants on both surfaces and the removal after 6 hours remain a consistent feature of use.

Vault caps sit in the fornices of the vagina covering the cervix and have no spring rim and are useful when vaginal tone is poor.

The cervical cap is designed to fit over the cervix and it may be useful for women who have a straight-sided cervix. A disposable silicone rubber cap called the Oves cap is now available. Once the woman has been fitted for size, she can buy these herself from a chemist. The Oves cap can be kept in place for up to 48 hours.

The vimule is a combination of vault and cervical cap and has a powerful suction capability and is used to cover the cervix that is small, irregular or partially amputated.

Other varieties of caps are being evaluated at present. The Lea’s shield and the FemCap are both made of silicone rubber and can be left in for up to 48 hours. One study found a failure rate of 10.5–14.4 per 100 woman years (Guillebaud 2007).

Female condoms

The Femidom is a polyurethane tubular condom consisting of a loose-fitting polyurethane sheath with a flexible ring at either end. It is inserted so that the condom lines the vagina. A soft but firm plastic ring at the entrance covers the genitalia and needs to be steadied in position during intercourse. This condom provides protection both from pregnancy and from sexually transmitted diseases. It has a failure rate of 5% (Guillebaud 2007). Like caps, these can be fitted prior to sexual intercourse. The female condom contains a spermicide-free lubricant. Being made from polyurethane, avoidance of oil-based products is not necessary.

The contraceptive sponge – Today Sponge®

The contraceptive sponge is a small, one-size, soft, doughnut-shaped foam device made from polyurethane, with a loop at one end for easy removal. It contains spermicide, and is normally placed internally into the vagina to act as a contraception method. The sponge prevents pregnancy in two ways:

It can be inserted in advance of intercourse, and has an effectiveness rate of 83–87%.

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC)

This term refers to four specific contraceptive methods: intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs), the intrauterine system (IUS or Mirena), progesterone injections and implants. These methods are particularly important as they are highly effective and do not affect fertility long term. In addition, they are useful for those who have compliance problems with other methods. NICE recommends that these methods should be discussed with all women who ask for information about contraception (NICE 2005).

Intrauterine contraceptive devices and intrauterine systems

Intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs) have been used all over the world since Biblical times. Nowadays, IUCDs are small plastic devices that are placed in the uterine cavity by means of a special introducer. All have copper or copper and silver stems that increase the efficiency of the device. The mode of action of IUCDs is complex and multifactorial. They act as a sterile foreign body in the uterine cavity and the resultant physiological action is potentiated by the addition of copper. The copper has a toxic effect on sperm and ova, preventing fertilization. It is rare to find viable sperm in the uterine cavity, making it very unlikely that IUCDs ever act as an abortive agent. It is also thought that the device causes some reduction in tubular contraction, thereby reducing the speed of the ovum along the fallopian tube, and there is some evidence of infrequent ovulation while the device is in situ. There may also be an increased production of prostaglandins in the uterus, which increases uterine activity and causes the expulsion of a fertilized ovum. A secondary action of inhibiting implantation is relevant when used as part of emergency contraception. The IUCD inhibits implantation and there is also a direct blastocystotoxic effect. There is no evidence that copper IUCDs increase the risk of ectopic pregnancies which are related to the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (Guillebaud 2007).

The introduction of an IUCD following delivery is generally delayed until 6 to 8 weeks postpartum, when involution of the uterus is likely to be complete. If it is inserted earlier, it may not remain in the optimum position and is more likely to be expelled. Particular care is required after caesarean section, to ensure that the wound has fully healed. In some cases, an IUCD is inserted at the time of termination of pregnancy, if requested by the woman.

A number of types are now available (Fig. 27.4). The GyneFIX, unlike the others, is frameless, consisting of six copper bands threaded onto a length of suture material. One end is provided with a knot, which is inserted into the fundus and acts as an anchor.

An increase in the length and heaviness of menstruation with an IUCD may make this an unsuitable method for women who already have menorrhagia. Women with dysmenorrhoea may find the pain is worsened by the introduction of a device. Women with recurrent infection in the reproductive tract may be advised to use another method. While the device does not introduce infection, any infection, particularly sexually transmitted infection, that may occur is likely to be more difficult to treat.

The devices remain in situ for 5–8 years, depending on type, and require only minimal supervision following insertion. They have an excellent record in preventing pregnancy, with a failure rate ranging from 0.3 to 3 per 100 woman years (Everett 2004). If pregnancy does occur when the device is in situ, removal is advised as soon as possible as there is an increased risk of mid-trimester abortion.

The Mirena intrauterine system (IUS)

This is a newer type of coil, the stem of which contains a progestogen reservoir that allows a slow release of progestogen. The effects are mostly local, so that ovulation frequently continues to occur. The proximity of the progestogen to the endometrium reduces its thickness, so that after an initial few weeks of erratic bleeding episodes the blood loss diminishes, and amenorrhoea is common (Szarewski 2006). The progestogen also causes a physiological mucus plug to form in the cervix, which safeguards the uterus from infection as well as impeding sperm penetration. Statistically, it is as effective as sterilization. It lasts for 5 years, and, following removal, fertility returns rapidly to normal.

Hormonal contraception

Oral contraception

Millions of women take oral contraceptives worldwide and it is the most commonly used form of contraception especially amongst young people. The oral contraceptive pill contains either a combination of oestrogen and progestogen (the combined pill or COC), or progestogen on its own (the progestogen-only pill or POP). The main controversies have concerned the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pill takers. The background risk for VTE in women not taking hormones is 5 per 100,000, compared with 60 per 100,000 during pregnancy. In women taking the COC, the risk varies from 15 to 25 per 100,000, depending on the type of pill. Midwives should always advise any women taking the pill to seek professional advice if they have any concerns, before stopping taking the pill.

Combined pill

This pill acts by suppressing the production of gonadotrophins from the anterior pituitary gland and thus inhibiting ovulation. It also alters the consistency of the cervical mucus, making it impenetrable to sperm; reduces the motility of the uterine tubes so that the sperm have difficulty in passing along the tube; and causes a change in the endometrium, making it unsuitable for implantation. The latter three back-up mechanisms are due to the action of progesterone.

The timing of administration of the combined pill is important, to prevent ovulation from occurring. For complete efficiency, the course should begin on the first day of the menstrual period and continue for 21 days. This is followed by 7 days without tablets (or, in some cases, ‘dummy’ pills), during which time withdrawal bleeding occurs. When taken correctly, the combined oral contraceptive pill is virtually 100% reliable (Guillebaud 2007). In cases of antibiotics being prescribed or the woman developing diarrhoea and vomiting, the COC will no longer provide reliable contraception. Other precautions such as condoms should be used during this time and for a further 7 days afterwards.

There are a number of contraindications to its use, so any woman who has a personal or family history of medical problems should seek advice. For women over 35 years, the COC is contraindicated if the woman either smokes or is significantly overweight with a BMI above 40, as there is an increased risk of thromboembolic disease, myocardial infarction and cerebral vascular accident. Other methods of contraception that do not contain oestrogen should then be employed.

After childbirth, the mother who is not breastfeeding may start the combined pill 21 days postpartum. The regimen of 21 days of pills followed by 7 pill-free days is followed. The oestrogen content of the pill is inclined to reduce lactation by suppressing prolactin and is also passed to the baby, albeit in small quantities, in the breast milk, so the combined contraceptive pill is not recommended for breastfeeding mothers. If started on day 21, it is effective immediately.

Progestogen-only pill

The POP is an effective method of contraception postpartum and is ideal for breastfeeding mothers. The progestogen does not affect lactation and any small quantity passing through the milk is not a problem for babies. The mother commences at 21 days after delivery and takes the tablets continuously from packet to packet without a break. Mothers should be advised that progestogen may cause erratic bleeding patterns, but this usually settles after a few months and the periods may gradually disappear. Breastfeeding mothers are unlikely to see any bleeding until breastfeeding is stopped.

Progestogen acts by causing cervical mucus to form a natural plug in the cervix which prevents the sperm entering the uterus, and also reduces the motility of the fallopian tubes. In some cases, the progestogen also causes suppression of ovulation.

The reported pregnancy rate with the progestogen-only pill is 0.3–3.1 per 100 woman years, with the rates reducing with age (Guillebaud 2007). The POP has to be taken within 3 hours of the same time each day, making this an unsuitable method if the woman has a bad memory or an erratic lifestyle. A newer POP, called Cerazette, has a 12-hour leeway for missed pills, similar to the COC. In addition to the normal mode of action, it will in many cases prevent ovulation and in many cases cause amenorrhoea, making it a highly effective pill.

Hormonal patch

The patch is the equivalent of the combined pill, containing oestrogen and progestogen. The patch is applied to a clean dry area of skin such as on the abdomen or upper arm. Each patch lasts for 7 days, when it is replaced, for a total of 3 weeks, followed by a patch-free week. The patch is resistant to normal bathing but some women find detachment of the patch a problem. There is some evidence that there is an increased cumulative effect of oestrogen using this method, with an increased risk of thromboembolic problems (Weisberg 2006).

NuvaRing

Similarly to the Evra patch, this ring contains oestrogen and progestogen, and is placed in the vagina for 3 weeks and then removed for 1 week. During this latter time, a withdrawal bleed will occur, and at the end of the 7 days, a new ring is inserted. It has a failure rate of 1–2 per 100 woman years.

Injectable contraceptives

These consist of a progestogen given as a deep intramuscular injection. The method has a low failure rate of about 0–1 per 100 woman years for Depo-Provera® and 0.4–2 per 100 woman years for Noristerat®. There is no evidence that it has any detrimental long-term effect on fertility; however, by nature of its mode of action, a return to fertility may be delayed. The average time from the last injection to conception is 9 months (Guillebaud 2007).

Depo-Provera (DMPA)

Depo-Provera 150 mg is most commonly used and is repeated at 3-monthly intervals. It acts by suppressing ovulation and making the cervical mucus impenetrable to sperm, causing changes in the endometrium which may lead to irregular bleeding or amenorrhoea. It is ideal for those with a poor memory and is often used by women who are unable to take the COC, e.g. smokers over 35 years who prefer the injection to the time limitations of the POP.

Depo-Provera can usually be commenced at 6 weeks postpartum provided that the woman has not had unprotected intercourse. If given before 6 weeks, it may provoke bleeding and, at a time when secondary postpartum haemorrhage may occur, could make diagnosis of pathology difficult. It does not affect lactation. There is some evidence that Depo-Provera reduces the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis and endometrial carcinoma (Bigrigg et al 1999).

Recent research suggests that Depo-Provera may adversely affect bone density, particularly if the woman is already at risk for developing osteoporosis in later life. Despite the lack of evidence from controlled trials, the recommendation is that it should not be used as a first-line contraceptive unless no other method is suitable. When Depo-Provera is used, ideally it should not be used for more than 2 years (Guillebaud 2007).

Noristerat

Norethisterone enanthate 200 mg may be given intramuscularly every 8 weeks; however, it is not licensed for long-term use and is used less often than Depo-Provera. It has a similar action to Depo-Provera but is less likely to cause irregular bleeding.

Future developments

Two once-a-month combined injectables, Cyclofem and Mesigyna, are being used in some countries but are not yet licensed in the UK (IPPF 2002). These cause a monthly bleed similar to the COC.

Implants

Implanon is a contraceptive implant currently used in the UK. It consists of a single rod containing a progestogen on a slow-release carrier. It is the size of a hair grip and is inserted superficially under the skin of the upper arm using a minor surgical technique and local anaesthetic. The implant lasts for 3 years before needing to be replaced. This regimen produces highly effective care-free protection with a failure rate of 0–0.07 per 100 woman years. Like other progesterone methods, it can cause irregular bleeding, although this often reduces with time. About 25% become amenorrhoeic (Reynolds 1999/2000). The mode of action is by inhibiting ovulation, preventing thickening of the endometrium and increasing the viscosity of the cervical mucus. The implant can be inserted from day 21 postpartum. When removed, fertility returns rapidly.

Emergency contraception

There are various reasons why women may need emergency contraception. These may include unprotected sexual intercourse (no contraception used, rape, failed coitus interruptus), failure of a barrier method (split condoms, dislodged caps), missed pills or injection, or expulsion of an IUCD. Whilst some parts of the menstrual cycle may be regarded as low risk for conception, if the woman has irregular periods or is unsure of her dates, no time can be regarded as safe. In practice, therefore, most women who present with such situations will be prescribed emergency contraception. There are currently two forms of emergency contraception available.

Emergency contraception (oral)

The most widely used form is an oral progestogen preparation called Levonelle 1500, which contains levonorgestrel (a synthetic derivative of progesterone). This is taken as soon as possible after the unprotected sexual intercourse and always within 72 hours. If taken within 24 hours, the percentage of pregnancies prevented is about 95%, whereas this drops to 58% if not started until 49 to 72 hours afterwards (RCOG 2000). The pills will only affect the reported episode of unprotected sexual intercourse and cannot protect the rest of the cycle. A new preparation called ellaOne, which can be used up to 5 days after unprotected sexual intercourse, is available on prescription. It is an important part of health education in the community, especially in schools and colleges. Oral emergency contraception can be obtained free from family planning clinics, GPs, or A&E departments. It can also be bought without prescription at pharmacies.

Emergency IUCD contraception

In the event of unprotected intercourse having occurred, a copper intrauterine contraceptive device may be fitted up to 5 days after the probable day of ovulation in that cycle. It can also be used later in the cycle if within 5 days of a single episode of unprotected intercourse (Guillebaud 2007). If used before ovulation, the IUCD interferes with the development of the follicle and thus prevents or delays ovulation. If used later in the cycle, its action is thought to inhibit implantation (Guillebaud 2007). Although less often used, it is a highly effective method of emergency contraception, with a failure rate of no more than 0.1% (RCOG 2000).

Sterilization

Tubal ligation or the application of potentially removable clips to the uterine tubes in women and ligation of the vas deferens in men are considered permanent methods of sterilization.

Before these procedures are carried out, it is essential that the couple is carefully counselled, with consideration being given to the psychosocial aspects of the decision as well as to the physical factors concerned with the procedure. Most couples accept sterilization without regret, but unless all eventualities have been carefully thought through, later events may lead to regret and some may use the operation to rationalize disturbances that arise later in life (IMAP 1999). A percentage of those who are sterilized request reversal at a later date, although the success rate is low. The advent of contraceptive methods such as the Mirena IUS, which is as reliable as sterilization, causes amenorrhoea in many cases and yet is removable, is an option for couples who are not totally sure about future plans.

Female sterilization, unless performed at the same time as a caesarean section, is seldom carried out earlier than 6 to 8 weeks after delivery and by that time any problems affecting the baby which could influence the couple’s decision are usually evident. The failure rate for female sterilization after 10 years is 1 in 200 and failure may occur several years after the procedure. The rate is slightly lower for older women (Everett 2004). It is worth noting that the effectiveness is less than that of the COC for women under 27 years.

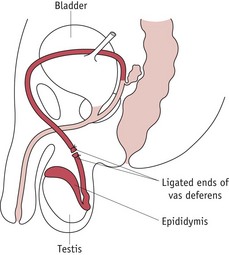

Vasectomy

This involves ligation of both deferent ducts (vas deferens) (Fig. 27.5). It is an easier and safer procedure than tubal ligation and can be done as an outpatient procedure under local anaesthetic. Ligation of the deferent ducts prevents the sperm reaching the seminal vesicle and ejaculatory duct. As spermatozoa may survive in the ducts for some time, the couple should continue to take contraceptive precautions until two sperm-free specimens of seminal fluid have been produced. This will take a minimum of 3 months. Again, skilled counselling is essential before a final decision is made. The man should understand that sexual desire and activity are not affected by the operation. Despite concerns about an increased risk of testicular cancer after vasectomy, recent studies have found no evidence to support this (Pryor 1999). The failure rate is 1 in 2000.

The role of the midwife in the provision of contraceptive advice

Many women conceive their first child unintentionally, and although this may result in a wanted child, it is not always possible to adapt well to unplanned parenthood.

Family planning is a specialist area, and midwives, whilst knowing the principles involved, also need to be aware of their limitations and when to refer the woman to a family planning clinic or domiciliary service. During discussions, the midwife may also detect cues which could highlight the need for specialist referral, help and advice, for example, in cases of medical disorders or where there are signs of psychosexual problems.

Factors to be considered

When the midwife discusses contraception with a mother and her partner, a variety of issues that may influence the woman’s choice need to be considered (Box 27.1). By discussing these factors, the midwife will be able to give more accurate advice to the woman about choices available, as well as advising her about the best place to obtain the contraception she wants or where to get further information. It is important that the mother does not assume she carries on with her pre-pregnancy contraception without advice. The midwife should not assume that the parents have a reliable knowledge of contraception, and confirming the knowledge before offering advice will quickly indicate if there are misunderstandings to be addressed. The midwife should appreciate that no prior contraception may have been used.

Timing to start contraception

The return of ovulation following delivery varies individually, but research suggests that the earliest possible ovulation occurs 30–35 days postpartum. It is therefore advisable to commence protection before this time. Mothers who breastfeed their babies on demand are likely to suppress ovulation for a long time. Exactly how long will depend on the suckling of the baby at frequent intervals and include at least two full feeds during the night. Babies who vary in their feeding requirement and occasionally sleep through the night will not stimulate enough prolactin to provide control of ovulation. The return of menstruation, when it occurs, indicates retrospective return of ovulation 14 days before. It is therefore important that the mother understands that printed information on packets of hormonal contraceptives does not relate to postpartum situations, and that such contraception needs to be commenced independently of menstruation.

When oral contraception is started on day 21 postpartum, it provides full protection from the first day. If commenced later, other precautions such as condoms should be used for the first 7 days. For any sexual intercourse after day 21, some form of contraception should be used. Following a termination or spontaneous abortion, contraception can be started with immediate effect.

Special groups

Teenagers

Young people remain one of the biggest challenges for the family planning services. Sexual activity can start early, sometimes as young as 10–12 years of age, usually unbeknown to the parents. Many have unprotected sexual intercourse partly due to their attitude towards risk taking and partly due to either ignorance about contraception and conception or fear of seeking advice (Andrews 2004). Many young people assume that approaching their GP or attending a family planning clinic will automatically involve information being passed to their parents and some youngsters will risk a pregnancy rather than seek contraceptive advice.

There is often a difference in attitude between girls and boys regarding sexual activity and contraception, with girls more likely to seek help than boys. Despite sex education at school, many young people are ignorant about basic issues such as contraception, conception and safer sex (Andrews 2004).

For young persons under 16 years of age, no contraception can be given, even condoms, unless they are shown to be Fraser competent. Following the Gillick ruling in 1985, the present legal situation is that under 16-year-olds can independently seek medical advice and receive treatment providing they can show that they are competent to do so. In contraceptive terms, provided that the doctor is assured that the young person understands the potential risks and benefits of the treatment/advice being given and the doctor believes that the person is likely to have sexual intercourse without contraception, the doctor is not breaking the law by providing contraception if it is believed that it is in the person’s best interest. The value of parental support is always emphasized and the youngsters are encouraged to talk to their parents about the consultation. All consultations are confidential regardless of age.

Older mothers

With an increasing number of women having babies in their 30s and 40s, contraception for this age group is an important issue. With increasing age, fertility is reduced, with fertility levels at 40 years being half those at 25 years (Guillebaud 2007). This suggests that some of the methods unsuitable for the highly fertile woman may be acceptable in the older woman. The COC pill can be continued until the menopause in the older woman provided that she is not overweight, does not smoke and does not suffer from migraine. For women with these problems, the POP is the oral contraceptive recommended for those aged over 35 years. The IUCD is another good method for the older woman and the Mirena IUS in particular is useful as it prevents menorrhagia, which is common in older women, and provides protection from endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Barrier methods are also popular, and for those around the menopause, the Today sponge® may provide sufficient contraception. Many women request sterilization and the midwife should be able to refer the woman for counselling.

Medical disorders

Any woman with a long-standing or newly acquired medical disorder needs expert advice in relation to contraception. Some drugs can interfere with the effectiveness of hormonal contraception and some conditions require specialist knowledge. Some women with conditions that make childbearing particularly hazardous, such as severe heart disease, may request sterilization or at least a highly effective method. Cardiovascular disorders, haematological disorders, hypertension, diabetes, migraine and liver diseases all require individualized advice (Guillebaud 2007). Midwives should ensure that the woman knows where to seek help before deciding on any particular method of contraception.

Through continuity of care, the midwife can provide advice and support to women regarding the choices that are available to control their fertility and plan their family appropriately.

Key Points

Andrews G. Women’s sexual health, ed 2. London: Ballière Tindall; 2004.

Bigrigg A, Evans M, Gbolade B, et al. Depo provera. Position paper on clinical use, effectiveness and side effects. British Journal of Family Planning. 1999;25(2):69-76.

Clement S. Psychological perspectives on pregnancy and childbirth. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

Department of Health (DH). Statistical bulletin. Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2006. London: DH; 2007.

Everett S. Handbook of contraception and reproductive and sexual health. Edinburgh: Ballière Tindall; 2004.

Guillebaud J. Contraception today, ed 6. London: Informa Healthcare; 2007.

Herdiman J, Nakash A, Beedham T. Male contraception: past, present and future. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;26(8):721-727.

International Medical Advisory Panel (IMAP). IMAP statement on voluntary surgical contraception, IPPF Medical Bulletin. 1999;33(4):1-4.

International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF). (2002) IMAP statement on hormonal methods of contraception. IPPF Medical Bulletin. 2002;36(5):1-8.

NICE. Long-acting reversible contraception (website) www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG30, 2005.

Pryor JP. Screening issues in male genital tract cancer. In: Kubba A, Sanfilippo J, Hampton N, editors. Contraception and office gynecology. London: WB Saunders; 1999:415-425.

Reynolds A. Implanon – a new contraceptive implant. Primary Health Care. 1999/2000;9(10):14-15.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. Guidance April 2000. Emergency contraception: recommendations for clinical practice. British Journal of Family Planning. 2000;26(2):93-96.

Social Exclusion Unit. Teenage pregnancy. London: Department of Health; 1999.

Szarewski A. Choice of contraception. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;16(6):361-365.

Weisberg E. Ortho Evra contraceptive patch. IPPF Medical Bulletin. 2006;40(1):3-4.