Chapter 70 Grief and bereavement

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

And can it be that in a world so full and busy, the loss of one weak creature makes a void in any heart, so wide and deep that nothing but the width and depth of vast eternity can fill it up!

With better antenatal care and advances in technology, childbirth is now relatively safe, and the birth of a child is usually a cause for celebration and joy rather than as in Dickens’ time, when childbirth itself held significant dangers for mother and baby (see Fig. 70.1). Sadly, even now, some babies do die – there were 3603 stillbirths and 2380 neonatal deaths recorded in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2006 (Lewis 2007, ONS 2006). In addition, it is estimated that 20% of confirmed pregnancies end in miscarriage before 20 weeks’ gestation.

Death is a part of life and therefore inevitable, but the death of a baby before, at, or shortly after birth, because of miscarriage, termination for fetal abnormality, stillbirth or neonatal death, is unexpected and against the natural order of things. It is unique, incomprehensible and unlike any other death. When an adult or a child dies, family members have memories to draw upon and a life to remember, but when a baby dies, parents grieve the lack of memories and any future with their child. For most parents the death of a baby is a significant and painful experience, regardless of the cause or gestational age. Parents depend on those in the health service, including midwives, to care for them and offer relevant information to guide them in the choices they have to make in this time of crisis.

It has only been in the last 15–25 years that the importance of grieving in achieving a healthy long-term outcome has been recognized. Research at the Tavistock Clinic in London has shown that, following stillbirth, bereaved mothers may suffer lifelong repercussions, including hypochondria, phobias and disturbances in relationships (Lewis & Bourne 1989). Appropriate professional help and support throughout the period are essential. Recognizing and responding to the parents’ feelings, sensing what they need and helping them to make informed choices are the challenges for professionals involved in caring for these parents before, during and after the birth of their baby (Schott et al 2007).

There is no right way to grieve, no set way of managing these difficult situations, and the midwife needs to learn through involvement with grieving families. The insights and suggestions for practice made in this chapter are based on what parents have taught professionals through sharing their particular needs.

Therapeutic use of ourselves

As individuals we naturally tend to turn away from looking at painful things, yet it is only in looking at ourselves that we can grow and ultimately help others. When a baby dies at or soon after birth, the exposure to the parents’ grief, sadness and pain may remind us of our own previous losses. Midwives themselves may have experienced pregnancy loss, or had difficulty in achieving motherhood, and this can impact on their feelings and experience of caring for women and families who also lose babies (Bewley 2010).

The process of helping is an active one, requiring a willingness to become involved, to share in the painful process, be congruent, express concern but remain separate, enabling the provision of sensitive care. This requires a high degree of self-awareness and recognition of our own feelings. This can be assisted by reflecting on previous life experiences that have been difficult – hurts experienced, broken relationships and other situations that have involved loss. This increases understanding of why we react in certain ways, our own limitations and when professionally we are likely to need support. As carers, if we are able to acknowledge and appropriately express our own anger, fear, sadness and embarrassment, other people’s emotions can be accepted more easily.

Interactions with people who are profoundly distressed engender feelings of inadequacy and helplessness, and this is in contrast to the normal healthcare role of helping ‘make people feel better and remove pain’. In bereavement, people cannot be made better – in contrast, healing occurs when people are able to feel and express their painful feelings.

When caring for bereaved families, the caregiver’s feelings often mirror those of the family – anger, sadness, confusion, a sense of failure. Management that recognizes and acknowledges the value of staff’s contributions in this work and their need for support helps to build individuals’ self-esteem in times of stress. Having access to a professional offering support or counselling based in the hospital can be as valuable for staff as it is for parents.

Looking after ourselves as professionals

Emotions are also felt physically and we carry them in different parts of our body – tension can be felt in the muscles of the shoulder, grief and sadness perhaps in the muscles around the neck, heart and stomach. Knowing which parts of our body are affected in times of stress, enables identification of ways of releasing these trapped emotions. Relaxation, vigorous exercise, listening to music, counselling or perhaps watching a comedy programme on television and seeking support are therapeutic outlets.

When people feel unable to deal with their own emotions, they develop protective strategies, such as distancing themselves from other people’s emotions, appearing unaffected and detached or conversely becoming very busy in order to avoid their emotional pain. They may develop negative feelings about themselves and their work and see themselves as failures. This can manifest itself as anger or resentment, which can colour family and professional relationships. Some of the warning signs of feeling depleted include experiencing chronic exhaustion, frequently feeling upset, difficulties in eating or sleeping or engaging with people; developing headaches or backaches; having nightmares; feeling worthless and pessimistic; avoiding contact with others; arriving late for work and leaving early.

Support and training for midwives working in partnership with families

Caring for distressed parents is difficult and demanding, and requires staff who are in a working environment that considers their needs and values them as individuals. Where appropriate support mechanisms are in place, midwifery teams are able to provide the best possible care to families. Bereaved parents are deeply grateful and remember the care they received throughout their lives (see website).

Bereavement skills training and support should be an intrinsic part of maternity care, whatever the setting (Schott et al 2007). Using counselling and listening skills is an essential part of the professional’s role and requires training, enabling midwives to care effectively when managing the death of a baby.

It is important that the midwife is aware of:

When staff do take the time to talk about their needs, their feelings, their reactions to situations and to understand their strengths and limitations, then working with families in grief is special and rewarding.

Understanding loss and grief

There are many theories explaining the grieving process, including Bowlby’s (1980) attachment theory; Kubler-Ross (1970) and Parkes’ (1972) series of predictable grief reactions which make up stages or phases of the grief response; and Worden’s (1991) ‘tasks of mourning’.

Reflective activity 70.1

Review your knowledge of the stages and tasks of the grieving process. Think of a hurt or loss that you have experienced. What were some of the feelings that you experienced associated with that loss? What help did you need?

Consider the behaviour of the last person you cared for who was coping with a death or loss – perhaps a woman who had a baby with a congenital abnormality. Did the person experience any of the recognized tasks in the process of mourning? Did the person move in and out of various tasks?

Which behaviour did you find hardest to manage as a practitioner?

These tasks of mourning are useful as a framework for understanding the grieving response following the death of a baby. Worden (1991) stresses that mourning, defined as the emotional process that occurs after a loss, is an essential and necessarily painful healing process. As with healing after physical injury, the process can be delayed or go wrong. The midwife has a significant part to play in helping parents begin to accomplish in particular the first two of the following tasks:

Accepting the reality of the loss

Initially, the parents are unlikely to believe the bad news and will be in a state of shock and denial, even when a death has been anticipated. Some bereaved parents cry uncontrollably, become hysterical or collapse, whereas others feel faint or numb and display few signs of emotion, appearing very controlled, calm and detached. The initial shock may last for hours or several days. This natural reaction is a form of emotional protection that disappears as parents gradually take in the full impact of events. Each experience of grief is unique and previous losses may also complicate the reaction to this current bereavement.

Parents may initially be unable to acknowledge what has happened and may manage by denying the reality. These parents need time and help to do what is right for them. It is not helpful for professionals to collude with denial and unreality, for example by avoiding talking about the dead baby, somehow making the child’s death seem less important – not showing or fully acknowledging its significance.

Midwives can help enable parents to gradually face reality. Being sensitive to parents’ needs, discussing what other parents have valued, offering choices, such as seeing and holding their dead baby, being involved as much as possible in the preparations for the funeral, and observing rituals and traditions, all help to make what has happened real. Families from different faiths need support for the mourning rituals appropriate to their culture (Thomas 2001, Schott et al 2007, CBC 2007d).

Working through to the pain of grief

As denial and numbness gradually subside, the bereaved parents usually experience the full impact of what has happened. Intensely painful feelings may last many weeks or months. This normal reaction to an abnormal event can be overwhelming as they think about what could have been and what the future now holds. Bereaved mothers are often incapable of thinking about anything or anybody else and are consumed with their child, themselves and how they feel. Painful reminders get in the way and are all around them. Innocent comments may get misinterpreted and cause distress and irritability. Susan Hill (1990), a writer and bereaved mother, eloquently described her extreme sensitivity after the death of her baby Imogen as ‘like having one skin less’, and appreciated the professionals who treated her gently.

It is normal to feel extremely sad, guilty, angry and resentful. Many parents struggle with guilty feelings about some aspect of their baby’s death, especially if they were initially ambivalent about becoming parents. Mothers may think about their behaviours or actions taken which they may blame for causing the death of their baby, such as running for a bus or carrying heavy shopping. These punishing thoughts can intrude into all aspects of their life.

Feelings of anger are often unexpected and hard to manage. The father or mother may feel anger for the loss of control that death brings; their anger can be directed at the medical and midwifery team for not recognizing the problem sooner, for not keeping their baby alive; anger at a God who allowed it to happen; and possibly anger towards their baby for not living and leaving them. Sometimes, unexpected resentment towards a family member or their partner adds to this exhausting and painful time.

Grief is not a mental illness, although sleeplessness, anxiety, fear, anger and a preoccupation with self can all add up to a feeling of ‘going mad’. These feelings are normal, and when experienced and expressed, slowly become less intrusive and frequent. Talking or writing about difficult experiences with someone who is interested and willing to listen is one of the healing ways to express grief. Attempts to cut short these emotions rarely help in the long term and may cause deep-seated problems in the years ahead. If grief is denied, or anger and guilt persist to the exclusion of other feelings over a number of months, help may be needed from someone trained in counselling.

Adjusting to an environment in which the deceased is missing

However short a time the parents had to get to know their baby, both during pregnancy and after the birth, facing a future without this child in the family is a difficult and painful process. Nothing can fill the aching void their baby has left and each day of life brings constant reminders of their baby’s absence. The future seems uncertain and frightening, while a tremendous effort is required to carry on as normal.

Grief is exhausting. It may take many months before the mother, particularly, is able to focus less on the sad events surrounding the death and regain some of her interest in life. Parents may also revisit the feelings of loss at what would have been significant milestones in their child’s life, such as expected date of birth, anniversaries and birthdays.

Emotionally relocating the deceased and moving on with life

This involves moving on to a different and new way of life without their child, whilst remembering and holding on to precious memories. It is a process of reinvesting in life again alongside the knowledge that their baby will not be forgotten. This can often feel like a betrayal and is perhaps more difficult than generally recognized.

When parents are able to move on with their lives together, there is a sense of putting the distress aside and looking to the future, whilst recalling memories of their baby and finding comfort and pleasure in these memories. It is a way of making life meaningful again and gaining back some control, so that the bereaved parents are not continually ambushed by memories of the death and trapped by painful feelings.

The importance of the loss

When a baby lives only a short time or dies before birth, because of miscarriage, termination for fetal anomaly or stillbirth, a common assumption is that the loss is not as significant. Pregnancy is a time of anticipation and many parents, particularly mothers, develop a strong bond with their baby long before it is born (Fig. 70.2). When a baby dies, parents grieve for all they had hoped and the lost opportunity of getting to know their child in a future they had planned together.

This grief response may be seen in families when a baby is born with a disability, who may experience the same feelings of loss of the healthy baby they were expecting and anger at the extinction of their hopes and plans. For some parents, the need for a caesarean section can result in a sense of failure and a reaction of grief for a different birth expectation.

A Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society (SANDS) teardrop sticker placed on the mother’s notes after a baby’s death alerts all professionals to the parents’ immediate and long-term need for sensitivity. At initial booking, it is important for the midwife to identify women who have had previous losses – miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death – and discuss the implications for the current pregnancy. This requires opening up a potentially painful subject; however, the midwife needs to be aware that this discussion allows the dead child to be acknowledged and their existence as an individual valued.

The midwife can also help prepare the woman for reactions and feelings that she might experience during the pregnancy and birth of this baby, which might include mixed feelings at the birth, and high levels of anxiety concerning the baby’s wellbeing and survival (Caelli et al 1999, Hunfeld et al 1997). The healthcare team can be alert to this mother’s needs, and ensure that support systems are available during the pregnancy and puerperium (Thomas 2001, Schott et al 2007). Bereaved mothers may be inclined to develop postnatal depression, particularly in cases of complicated grief.

Different parental responses in bereavement

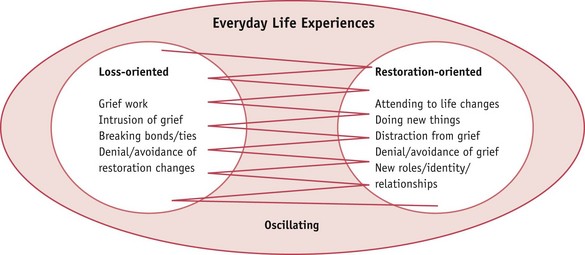

Grief is solitary – even when a couple are grieving, each parent can feel alone in his or her grief, and normal patterns in relationships may become disrupted. As a father’s and mother’s needs are different, they may find they are unable to communicate with one another, to express the awfulness of their feelings. Women naturally tend to be more loss-oriented and focus on their loss and the emotions they are experiencing. They need memories and to constantly recall, be reminded of and talk about their baby who has died. Men are generally more restoration-oriented – they want things to return to normal and prefer to look to the future. Although they feel the loss, it is a loss not to be acknowledged (Puddifoot & Johnson 1997) and this response may be interpreted by their partner, and others, as being uncaring and less interested in their baby. The dual process model of grieving (Stroebe & Schut 1999) illustrates the way bereaved people engage in both loss-oriented and restoration-oriented grieving behaviour and oscillate in healthy grieving between the two behaviours (Fig. 70.3).

Figure 70.3 A dual process model of coping with loss.

(From Stroebe and Schut, 1999, with permission.)

The midwife needs to assist the couple to understand the different perspectives and ways of dealing with grief, so that they are able to support each other through this period (see website).

Supporting parents

Women and men say that the most supportive care is when professionals are able to help and encourage parents to ‘parent’ (CBT 2003a, 2003c, CBC 2007a), to be involved with their baby before and after death.

Both parents need support and both need information, though it should be remembered that it is often difficult for distressed parents to absorb and understand what they are told. It is useful to ask the parents to explain to you what they have understood. They may want more information about their baby’s condition or to know more about the reason for their baby’s death, and so any help the midwife can provide in obtaining this information will be welcomed (Schott et al 2007).

Parents appreciate staff who offer them warmth and understanding, are able to show they care and are not afraid to express their own emotions. In expressing feelings, professionals act as role models and tears are unlikely to be viewed negatively if genuinely felt. However, parents need support and should not have to be concerned about their midwife’s feelings or experiences of grief.

Touching is the most basic form of comfort and communication. This may be a hand on the arm, or an arm around the parent’s shoulder. Parents need the opportunity to talk about how they feel with someone they trust and if possible to be able to express their emotions openly. It is not helpful for parents to be told how they feel; only they can know. Parents do not want to be told the stage of grief they are seen to be at.

Often midwives spend many hours with a couple. Talking about everyday things, offering opportunities for normal conversation, can be useful, as well as being quiet and recognizing that just being there and being available to the parents is valuable. Self-aware midwives can be intuitive and trust their own instincts when interacting with parents; listening carefully is the key.

It is important to talk to both parents and acknowledge that both parents are grieving. It is helpful to provide information to parents who may want to do the practical things that have to be done, together.

All staff – hospital and community midwife, doctor, chaplain, counsellor and social worker, support staff and, later, GP and health visitor – need to adopt a team approach with everyone being aware of the procedures to follow when a bereavement occurs. Good team relationships are essential to provide the best possible care to bereaved parents.

Breaking bad news

Whether their baby’s death is anticipated or occurs suddenly, parents value the support of caring professional staff. Parents remember the way they are told bad news and the words, actions and attitudes of the professionals involved. This places a heavy burden on the professional who has the responsibility of telling parents such sad information. Explaining bad news involves both parents together whenever possible, and should take place in a private and appropriate room. Parents appreciate honesty and a genuinely caring approach by the professional in such a situation. Clear, unambiguous information needs to be sensitively given, in a way that uses language the parents understand. An interpreter needs to be present when parents do not speak or understand English. Children in the family must not be used to translate and convey information to parents.

Information may have to be repeated more than once. Questions should be answered as honestly as possible and allowances should be made for parents to respond in their own time. Offering time and actively listening to what they have to say avoids parents being left with confusing information. Parents remember when you refer to their baby by name and acknowledge the significance of their baby’s death. Saying that you are sorry that their baby has died does not mean anyone did anything that requires an apology.

The scan – the diagnosis

The ultrasonographer may be the first person to know that something is wrong. When an appointment is made for a scan, the parents need to be clearly told and understand that the scan is being performed to detect any problem that their baby may have and that a partner or friend may accompany the mother.

When the scan reveals an abnormality or that their baby has died, the sonographer present needs initially to explain to the parents that there is reason for concern. These situations require the presence of a doctor as soon as possible to confirm a possible diagnosis and future course of action. The mother and father should be offered an opportunity to see the scan of their baby while the doctor explains honestly and sensitively what is wrong. All staff need to be familiar with the unit policy to be followed in such a crisis. When further tests are necessary, these need to be carried out as soon as possible and the reliability of these tests and any risks involved carefully explained.

Parents are likely to be in shock and the couple need privacy and time to absorb what they have been told and their options. Keeping a scan photograph in the mother’s notes for collection at a later date is helpful. It is the responsibility of the midwife looking after these parents to inform them that the community team and their GP will receive all the relevant information. This liaison between the hospital and the community is vital for parents when leaving the hospital.

Reflective activity 70.2

What system does your unit/service have in place to ensure effective communication when managing a pregnancy loss or the death of a baby? How do you personally ensure that a death has been appropriately communicated to colleagues in the community including midwives, GP and health visitors?

Miscarriage

Miscarriage is the loss of a pregnancy before 24 weeks’ gestation. For many people the miscarriage of their baby at any gestation in pregnancy is a devastating experience (Fig. 70.4) and especially so when couples have previously experienced infertility or an ectopic pregnancy. Pregnancy and the feelings associated with becoming parents are unique. Parents find phrases used by professionals such as ‘blighted ovum’, ‘missed abortion’ or ‘non-viable fetus’ unhelpful, meaningless and hurtful. During the second trimester, most parents-to-be acknowledge openly that they are expecting a baby and a miscarriage may be experienced as the stillbirth of their baby. There are no set rules to follow in caring for people at such sensitive times and staff need to recognize and respond to parents’ very varied feelings, trying to sense what each individual needs. Hospitals are now being asked to offer parents a form of certificate acknowledging the birth of their baby at less than 24 weeks’ gestation should the baby be born with no signs of life (Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society – SANDS).

Termination due to anomaly

When informed about an anomaly detected in pregnancy, parents in distress may make decisions in haste which they later regret. Staff should encourage parents not to hurry decisions, to acknowledge how difficult it is for them at this time and suggest they take time together, preferably at home, before making any final decisions. Parents need clear, unbiased information, in understandable language, about their baby’s condition and the options available to them, including information about the mode of delivery. Providing written information before any decisions are made is crucial. A leaflet from the organization ARC (Antenatal Results and Choices) is useful to parents. Some choose to continue with their pregnancy and need support to do what is right for them, whether their baby will have significant problems or will not live. Whatever the outcome, their choice will affect the rest of their lives and their decision will involve grieving for the baby they had been expecting.

When parents have made a decision to end the pregnancy, they may not feel able to experience or express any attachment to their baby. The grief of these parents is complicated and the guilt often profound, as they have taken the responsibility for ending the life of their child; for some parents, their attachment is as significant as if their baby had survived. It is important for staff not to be judgemental and to offer as much emotional support as is needed. The decision made by parents is no indication of the amount of love they have for their baby.

Labour when a baby has died or is not expected to live

A baby who has issued forth from its mother after the 24th week of pregnancy and has not at any time after being completely expelled from its mother’s body breathed or shown any signs of life is a stillborn baby.

(NMC 2004:42)

Hospitals can be impersonal, frightening places and the sensitive care offered by a midwife is crucial. Providing an atmosphere in which parents are able to trust the professional caring for them is enhanced by having a suitable, comfortable and private bereavement room. The entire team needs to know when bereaved people are admitted to the unit.

On meeting these parents, the midwife needs to immediately acknowledge the situation and say how sorry he or she is, then to spend time listening to parents, building a relationship and responding to their varied needs and feelings. Not all parents realize that the labour and delivery of their baby will need to be physically the same as giving birth to a live baby. This realization may be hard to comprehend and may cause anger and disbelief.

To find myself carrying death and, even worse, being told I had to give birth to death, was the most horrific scenario.

Practical considerations

The mother who is expecting a stillbirth or late miscarriage requires significant psychological support, but the principles of care during labour for this woman are similar to those for a woman expecting a live birth.

In situations where a baby has died in utero, the mother may request a substantial amount of pain relief, not being aware that later on, the birth of her baby may be a time she wishes she could fully remember. Experiencing the labour enables a mother to begin to face the reality of giving birth to her baby.

Discussing a birth plan and having some control in a situation where parents feel powerless is psychologically valuable. These choices provide important memories on which to focus in the process of grieving.

I didn’t have any control over the situation at all and I don’t think either of us really knew what was happening until well after.

The woman may be in a state of shock, and therefore it is preferable to provide good continuity of care, and the midwife providing that care should be aware of the possibility that information may not be as easily understood, and that this information needs to be simple and accessible, and may need to be repeated.

This woman may be at an increased risk of complications, such as inefficient uterine action, infection, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and therefore the care provided must include monitoring of maternal observations and wellbeing, and scrupulous attention to asepsis during examinations. The midwife needs to be aware that the woman is often so immersed in her grief that she will pay scant attention to what she may be physically experiencing.

Having a general anaesthetic for an emergency caesarean section creates what is a potentially complicated grief reaction. These mothers need additional help in facing the reality of what has happened: that their baby, who they will have no recollection of having, has in fact died (Fig. 70.5).

Unexpected death of a baby at or soon after birth

When there is serious cause for concern in labour or at delivery, it is essential that the parents are informed immediately of what is suspected and that a doctor is asked to speak to the parents and provide confirmation of the prognosis. The designated midwife needs to be present, to provide additional support to parents and clarify any information as needed.

In this situation, practitioners themselves may experience trauma and guilt and need to have time, opportunity and support for reflection and review.

Neonatal death

Following the birth of a baby who is not expected to live, parents need to be honestly informed and given time to gradually absorb the painful information. They need reassurance that nothing more can be done for their child and helped to be involved in any decision regarding their baby. When a decision is made to withdraw active treatment, it is vital that it is made with the parents, and that they are provided with whatever time is necessary to make these difficult choices (McHaffie 2001). The availability of a bereavement room in the hours leading to a change from intensive to palliative care will provide parents with the privacy, time and space they need with their child (Fig. 70.6). Some parents prefer to be alone; however they need to know when and where staff can be contacted.

Spending time with their baby

Initially some parents may actually fear seeing their dead baby; they may be afraid that it will make them more attached and therefore make saying goodbye even harder. For some parents, this will be their first experience of death, and they may be frightened of what their baby will look or feel like. Frequently parents are unable to accept fully what has happened and may manage by denying the reality. There is no need for parents to make any decisions in a hurry. Time and understanding are required with grieving parents, as their denial is a form of emotional protection and with time it will lessen. It is useful for the midwife to explain to the parents that other parents have also felt concerned about seeing or holding their baby, and have later valued the time they have had with their baby. NICE guidelines highlighted ‘the findings of (Hughes et al 2002) which suggest that women should not be encouraged to hold their dead baby if they do not wish to’ (NICE 2007:196). This statement has been challenged by leading organizations, including SANDS and the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), and leading workers within perinatal bereavement (Schott & Henley 2009) as being open to misinterpretation and running the risk of denying many parents an important experience. This guidance is being reviewed. What the guidelines should underline for professionals is the importance of preparing and supporting parents to make an informed choice at this crucial time, and that this will be individual to each family.

These hours after the birth are immensely valuable. Nothing in life can prepare parents for such a tragedy and observing the staff’s tenderness and interactions with their baby will remain in the parents’ memories for a lifetime.

Washing and dressing the baby after death

This may be the one opportunity parents have to choose clothes for their child (Fig. 70.7). Staff can make a difference by providing information enabling parents to make choices, including:

Figure 70.7 Sophie’s parents appreciated being able to see her little feet and choose her dress themselves.

(By kind permission of the parents, and not to be reproduced without permission.)

It should be unit policy to have a selection of baby clothes from which parents can choose to dress their baby and later keep when they return home. In the future, parents will treasure everything that gives them a sense of their baby. Clothes their baby has worn are best left unwashed, as initially the smell of the clothes will provide parents with a tangible reminder of their baby.

The importance of memories

Midwifery and neonatal staff who help parents to get to know their baby in the brief time they have together provide a source of precious memories, which will be vitally important in the months ahead (Schott & Henley 2001). Some units now offer parents a memory folder and memory box which can be used to store any special mementoes of their baby. This can include photographs, their baby’s name-band, foot and hand prints, a lock of hair, a page where words can be written by anyone who knew the parents and baby, a blessing or naming card, letters and perhaps the clothes their baby wore, the anniversary cards and gifts that people choose to collect and keep for the future.

The value of photographs

For many people, scan and camera photographs of their baby who has died are immensely important. These parents will be interested in what their baby looked like and will value pictures that clearly show details – their baby’s profile, the tiny hands and feet, and perhaps sensitively taken pictures of their baby naked. These photographs help parents to face the reality of what has happened, provide evidence they had a baby and that their child died. Parents may like to know they can have a photograph of themselves holding their baby, a family picture with their other children or the grandparents, or with midwives who cared for them. When a twin dies, taking care and time to photograph the live twin and the dead twin together (Fig. 70.8) is something parents may not naturally consider and yet may so value in what can be a complicated grief process in the years ahead. Later in life the surviving twin may well be interested to know about the sibling who died and to know that his or her twin was acknowledged and mourned – parents in multiple birth and death situations have a great deal to manage and can find this information helpful. A photographic memory guide providing information and practical guidance is available for families and professionals (CBC 2007b, CBC 2007c).

The postnatal period

Physically, the woman requires a high standard of postnatal care, including psychological support, physical assessment, and educational elements of ensuring the woman understands the normal physiological process of the puerperium, and what can be considered normal.

The midwife needs to discuss with the woman where she wishes to be cared for whilst in hospital. The choice is usually between a rapid discharge home, a single room in the antenatal and/or postnatal ward, or on the gynaecology ward. Previous research and experience suggests that some women may wish to have contact with other mothers and babies, while some would wish to be in their home environment, and some may actually feel abandoned after being sent to the gynaecology ward (Hughes 1987). Thinking that a woman can be ‘protected’ against the sounds of a crying baby may be too simplistic a view.

Wherever the woman is cared for, continuity of carer must be an aim, and the same principles of keeping information simple and accessible should be retained. A difficulty which many women experience and find especially hard will be when a few days after the delivery, the breasts fill with milk, which is a tangible reminder that there was to be a baby to suckle. Previously, bromocriptine has been prescribed to suppress lactation; however, recent concerns with women experiencing serious cardiovascular complications, including stroke and hypertension, has led to reluctance to use this. The woman needs firstly to be told that this may happen, informed that pain relief can be prescribed, and advised to wear a supportive brassiere. For some women, homeopathic remedies may be useful: one study indicated that jasmine flowers were effective (Shrivastav et al 1988).

Postmortem examination (autopsy)

All staff should receive appropriate training in how to sensitively discuss consent for a hospital postmortem with parents. Although a doctor may request and provide information for written postmortem consent, it is often the midwife to whom parents turn for further information, clarification and support, and all midwives must understand the ethical, legal and emotional responsibilities involved (HTA 2006). Obtaining parents’ consent should be seen as a continuing process, not limited to the signing of a form.

Key principles to highlight with parents (see website) are as follows:

Graphic details about the postmortem examination may be too overwhelming for some parents, and they need to be offered the opportunity to choose how much or how little information they would like and given time to consider their decision and ask any questions. Sensitive and caring communication is essential in this situation, to ensure consent is a process and is properly sought. It is important that parents feel in control, understand what they are consenting to and have the right to say what happens during and after the postmortem examination (see website).

It is important that the consultant involved in the baby’s death meets with the parents and discusses the findings of the postmortem within 4–6 weeks of the death. Many parents value an opportunity to talk to the pathologist before or after the examination.

Coroner’s postmortem

In the event of a sudden or unexplained death, a coroner’s postmortem is legally required and in this situation the parents’ permission is not requested. The parents’ need for time, information and sensitive support is vital. The coroner is responsible for informing parents if organs and/or tissue have been retained to ascertain the cause of death. The length of time an organ will be retained and when it will be returned to the body prior to burial or cremation should be discussed. It is crucial that parents are informed that, with their consent, tissue blocks and slides may be kept as part of the medical record. Parents need to understand that while enquiries into the cause of their baby’s death are underway, the death cannot be registered and so final funeral arrangements cannot be made. Normally, however, when an inquest is required, it is held very soon after the death and the funeral need not be delayed. Information regarding a coroner’s postmortem and whether an inquest is needed should be available for parents in written format (INQUEST 2003).

Organ donation

Parents will not necessarily consider asking about heart valve or other tissue or organ donation. They will rely on – and appreciate – the professionals who care for them to provide them with information to make informed choices; it is therefore important that information is informed by circumstances when organ donation is possible and in particular that a cause of death is known. Parents who are not asked may wonder why and later may even resent this lack of information.

Parents need to have clear information and explanations from the donor team in their particular region, and would need to be aware that heart valve donation (usually referred to as tissue donation), carried out up to 48 hours after the death of a term baby, may require a large part of the heart to be retained. If a donation from their baby is to be used, blood samples will need to be taken from the mother, father and baby to test for HIV, hepatitis B and C and syphilis.

Respecting parents

As soon as possible after their baby’s death, a visit from a senior doctor, accompanied by their midwives, is valuable for parents and provides acknowledgement of the importance of their baby’s existence. They will need time with a designated person who can help them with the practical arrangements, to understand what steps to take, legal requirements, what the hospital can and cannot arrange and choices about the funeral. Providing written information, devised in consultation with families, is useful so parents can refer back to it as necessary whilst in hospital and also at home.

Spiritual needs

All cultures have rituals and traditions that are followed in a major life event, and these provide an opportunity to honour the importance of what has happened and help reality to be faced. When religions and cultures are different from our own, a lack of knowledge and understanding of specific spiritual needs may leave professionals feeling even more helpless, and families dissatisfied (Arshad et al 2003). Asking parents what they would like, offering them time to explore what is important for them, will be invaluable. Some parents who never go to church may find comfort in a visit from the Hospital Chaplain, a blessing or baptism for their baby, while others may like a visit arranged with their own religious leader. Many hospitals today keep a Book of Remembrance in which parents may make an entry, either soon after the birth or at a later date.

Other parents who have a deep faith may choose not to have a religious ceremony. It is best to refrain from talking about your personal beliefs with bereaved families, but to be open to what may be appropriate for and a comfort to them. This illustrates the need for the midwife to be knowledgeable about different cultures and religions and their rituals, but not to make assumptions about what parents from a particular group will wish to do following a bereavement (Schott et al 2007, CBT 2003b, CBC 2007d).

Involving brothers and sisters

It can be difficult for professionals to raise with parents that they may need to consider the involvement of their other children when a baby brother or sister has died. Children can arouse strong feelings in adults. For midwives, they may evoke memories of their own childhood, their own children, or perhaps the children they had hoped to have. Professional staff increasingly recognize the importance of work with adults, but children and their emotions have often been ignored.

When a baby dies, parents may be reluctant to involve their other children. They themselves are grieving, feeling helpless and overwhelmed and may be uncertain about their own ability to regain control. It is natural for them to want to protect their children from painful situations and it can be helpful if they are told this is a normal reaction. However, this stance may leave the siblings confused, unprotected from their fantasies and unsupported in their feelings.

Communicating with siblings

The decision is not whether or not to talk to children, but who will do the talking, when and how, as it is impossible for parents not to communicate with children. They read body language, overhear conversations and notice changes in routine. Momentous situations in a family cause changes, and children quickly sense when something serious is happening. They require clear, simple, truthful and often repeated but brief explanations about what has happened, and what may happen next. Although the children will not have known the baby and so are unlikely to be deeply grieving for their brother or sister, they will be affected by the grief of their parents.

Children do not need protecting from their feelings, but support in them. Young siblings will not grieve in the same way as older children and often express themselves through play, drawing or with friends.

Children’s reactions and understanding

Children have a shorter concentration span than adults and cannot tolerate intense emotions for very long. This does not mean that they are not sometimes upset and sad. Few children under the age of 5 will understand the permanence of death. They think in literal, concrete terms and therefore metaphors or euphemisms such as ‘lost’ or ‘gone away’ are confusing. Children need adults to say the words ‘has died’ or ‘is dead’. By 6 years of age, most children begin to understand death as permanent and that it can happen to them.

Preparation before the death

Whenever possible, it is helpful if parents prepare their other children when their baby sibling is not expected to live, giving honest information appropriate to their children’s age. Children need to understand that most sick babies in the hospital get better and go home, but sadly sometimes babies die. It is important not to overwhelm children with information but to be guided by them and to answer their questions honestly.

Preparation after the death

Most children who have been carefully prepared and have chosen to see their dead baby brother or sister are not afraid and generally gain an understanding of death and what has happened (Fig. 70.9). What children do not know or are not told about, they often make up and their fantasies are usually worse than the reality. Sometimes they experience feelings of guilt, especially if they were not looking forward to a new sibling. They need to be reassured that the baby’s death had nothing to do with their thoughts or actions, and that their parents love them and life will not always be so sad.

Figure 70.9 Naomi holding her baby sister Katie after she died.

(By kind permission of the parents, and not to be reproduced without permission.)

Parents may be concerned that frightening memories of a dead baby will leave their children with upsetting images – this is unlikely, especially when the children have been prepared for what to expect (Fig. 70.10). Children respond well to factual explanations of death and having information such as: ‘When people die it means their body doesn’t work any more.’ It is useful to explain that the baby may feel cold to touch and that the skin may be mottled and the baby’s lips or skin may be blue. It is not helpful to liken death to sleeping because people who are asleep are not dead and their bodies work very well (CBT 2003c, CBC 2007e).

Attending the funeral

Although some parents and grandparents feel that children need to be protected from being present at the funeral, children themselves usually say that they find it helpful to be there. They need to be prepared for and included in the family’s rituals of mourning. To be excluded from these events can widen the gap between the grieving parents and the child. However, a child who is frightened about attending a funeral should not be pressured or forced to do so. Some other way can be found for the child to say goodbye – such as putting a letter or flowers in the coffin, lighting a candle, saying a prayer or visiting the grave.

If children want to attend the funeral, thought needs to be given to the support that will be required. They need to know what will happen and be given the opportunity to ask questions. They may like to take an active part in the service by choosing a favourite song, poem or reading. It is often a good idea for the children to be cared for by an adult who is close to them during the service, to relieve the parents at such an emotional time.

How professionals can help

It is important for staff to make a direct offer of help to families and ensure there is time to discuss parents’ worries and anxieties. However, parents are individuals and not all of them will feel able to involve their children directly or tell them about the death immediately. Different cultures will have different ways of dealing with death, and sensitivity is paramount when offering parents information so that they can make informed choices, for example, a photograph to take home to the children of their brother or sister who has died. It is helpful for staff to explain to parents that they may meet resistance from grandparents and others who did not receive this care years ago.

Professionals can suggest children might like to have something special for themselves – perhaps a footprint on coloured paper they have chosen or a photograph of them with their baby brother or sister. Children are helped if they are allowed to share in and create memories.

Family and friends

Grandparents too will be grieving and perhaps feeling guilty that they are still alive when their grandchild has died. They will grieve for their grandchild and for the sadness of their son or daughter. They may be a main source of comfort to the grieving parents in the months ahead and are more able to share this grief with the parents if they have been involved from the start. Other family members and friends may experience similar feelings of grief and unhappiness for the bereaved parents.

Involvement of a close family friend can also be supportive, particularly if for whatever reason a mother is having to face bereavement on her own without a partner. It is important to have someone to share the few memories of a baby’s brief existence and to help when taking decisions such as funeral arrangements.

Taking a baby home

Parents appreciate information about taking their baby home with them before the funeral – this can usually be arranged with the local funeral director (CBC 2007f, CBT 2003d). Hospitals are large and impersonal and parents may prefer the family to have the opportunity to see their baby and say goodbye in familiar surroundings (Fig. 70.11). When there is a coroner’s postmortem, permission must be sought from the coroner (CBT 2003e, CBC 2007g).

Figure 70.11 Colette, Elizabeth Ann and Eugenie with their brother Benedict’s coffin at home before his funeral.

Leaving hospital

When parents leave the hospital, where possible, a member of staff should walk with them out to their car or taxi. It is crucial that community staff are aware of the baby’s death and parents know who to contact once at home. Hospital policies need to be clear and enhance liaison between hospital and home in order to provide continuity of care for bereaved parents.

Making an appointment for the parents to visit the consultant again, and perhaps the midwife who cared for them, within 6 weeks, for a follow-up bereavement visit is useful. They can share again what happened at their baby’s death or maybe have explained anything they did not understand in crisis. This time can be a valuable way of finding out what support the parents have or may need.

Registration of the death

Legally, when a baby is born dead before 24 weeks’ gestation there is no birth certificate or need for registration. However, if the parents choose to have their baby buried or cremated, they will need written confirmation of the birth from the doctor or midwife attending the delivery. Some units issue a form/certificate to record that the parents are taking their baby’s body, and this is formally recommended as best practice. This certificate also serves to recognize the baby’s existence and can become an important memento.

After 24 weeks’ gestation, when a baby is stillborn, the doctor or midwife who attended the delivery gives the parents a Medical Certificate of Stillbirth and should explain that the stillbirth of their baby must be registered by either or both parents at the registry office within 42 days.

When a baby is born alive, regardless of gestational age, and then dies within 28 days of birth, by law a doctor must confirm the death and provide a medical certificate to enable both the birth and death to be registered within 5 days of the death.

When parents are married, either or both can register, but when parents are unmarried, the registration needs to be done by the mother. The baby’s father should accompany her if he wishes his name to appear on their baby’s certificate.

Respectful disposal

Parents of babies born dead before 24 weeks’ gestation who choose to arrange a burial or cremation for their baby themselves, may need help with planning a ceremony, which can be held in the hospital chapel, in a church, or at the crematorium or cemetery (DH 2005, RCN 2001). Parents do not generally know about how to manage this and may welcome the suggestion if it is made to them. Other parents may prefer not to be involved in the arrangements themselves but will want to be reassured that the hospital will treat their baby’s body with respect (RCN 2001).

All parents need information about the options available to them. An information sheet with the relevant costs and considerations is valuable, as also is plenty of time, ensuring parents are not rushed and are able to make informed choices.

The months ahead

In order to begin to heal the pain of a traumatic loss, parents need to find a way to express their feelings and to communicate these feelings to a caring supportive person. Parents continue to grieve for their baby throughout their lives. They know they can never replace the baby who has died – grieving is about remembering, not forgetting. But it is the very absence of memories that makes grieving so hard when a baby dies. Parents are likely to feel a bond with the staff who cared for them and their baby. Appropriate care needs to be available in the months following the death on the unit. Parents need to know how to access support no matter how long it is since their baby died (Jennings 2001).

In a busy unit it is not always possible for professional staff to give parents as much time as they need, both at the time of the death and on return. A designated bereavement counsellor is in a position to support the parents and the staff. Using counselling skills and working as a counsellor are two different tasks. Being a counsellor requires a professional qualification, and is a skilled task for which aptitude, training and experience are necessary. It can only happen if the client has asked for counselling.

Bereavement counselling takes time and is best offered as a home or hospital visit after the baby’s death. The crucial times appear to be 3 and 6 weeks after the death and also 3, 6 and 12 months. Parents say that just knowing that as a couple, they can see a counsellor, perhaps once a month, helps them to manage their feelings and relationship. The bereavement counselling session gives them permission to talk about their feelings and their relationship and helps them to recognize that it is normal to grieve.

Return visit to the hospital unit

Some parents want to come back to the unit to see the midwife in the antenatal clinic or to see the person who cared for them and their baby. The opportunity to talk through what happened at the time of their baby’s death, particularly if the mother had a general anaesthetic, can be very valuable. Ideally, a time should be arranged so that when parents arrive on the unit someone expects them and they have a clear idea how long the member of staff can spend with them. Parents may want to return around the first anniversary of their baby’s death, and it is useful to be aware of this.

Support agencies

There are a number of voluntary organizations (see website for Additional resources) which offer support to bereaved families in the form of helplines, parent support groups and resources for grieving families. Most parents will also welcome information about the local support groups. These agencies, such as SANDS and the Child Bereavement Charity (formerly the Child Bereavement Trust), now the Child Bereavement Charity (CBC) are sources of information and support, and are also involved in developing literature and resources for bereaved parents and professionals (see website).

Reflective activity 70.3

Gather information about facilities, protocols, information leaflets and booklets that are available in your unit for women and their families who have lost a baby, or are facing perinatal bereavement. Review the material so that you are aware of the content, and where to get further information on:

Review local support groups and make sure you have contact details in your personal resource file.

Conclusion

The essence of working with bereaved families is to respect their wishes and feelings whatever they may be; to offer them as much time as they need to talk about what has happened; to really listen to what they have to say; to ensure they have as much information as they want and that they have understood it; to answer their questions honestly; and to make sure they have someone to contact for support in the future.

The Chief Medical Officer’s recommendation that all NHS trusts should provide support and advice to families at the time of bereavement highlighted the need for the role of bereavement advisor and recognized the need for training in all aspects of dealing with grieving families (CMO 2001). The Child Bereavement Charity (CBC) (originally the Child Bereavement Trust set up in 1994) has developed an audit model for the monitoring and evaluation of bereavement services (CBT 2003f, CBC 2007h).

Midwives have to balance caring for the complex needs that the mother and her family have, which must include a consideration for physical, social, psychological and spiritual needs, at a time when she requires a high level of sensitive and skilled care (Thomas 2001). This balance requires significant self-knowledge and an ability to be truly ‘with woman’ through her pain and sadness, in order to support and guide her through this period. An awareness of their own needs and those of their healthcare colleagues is also imperative in ensuring a strong and supportive team.

Working with grieving parents can be difficult and emotionally draining, but knowing that the family have been helped through one of the worst periods of their lives, by what was said or done making a difference, can be immensely rewarding.