ANTERIOR PART OF NECK

Neck

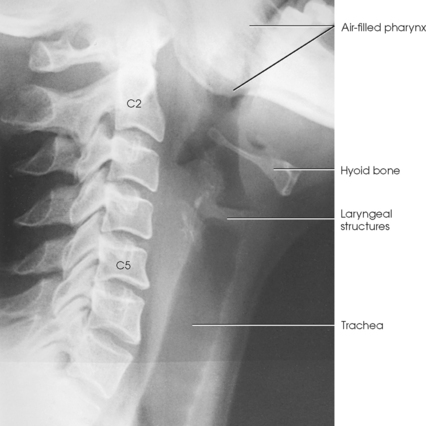

The neck occupies the region between the skull and the thorax (Figs. 15-1 and 15-2). For radiographic purposes, the neck is divided into posterior and anterior portions in accordance with the tissue composition and function of the structures. The procedures that are required to show the osseous structures occupying the posterior division of the neck are described in the discussion of the cervical vertebrae in Chapter 8. The portions of the central nervous system and circulatory system that pass through the neck are described in Chapters 24 and 25.

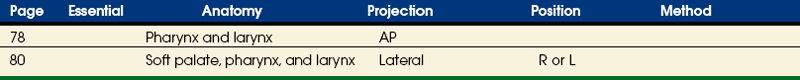

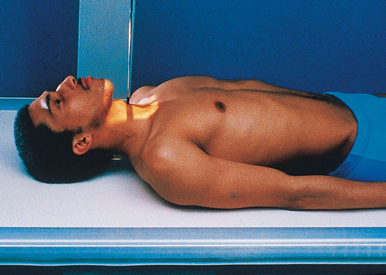

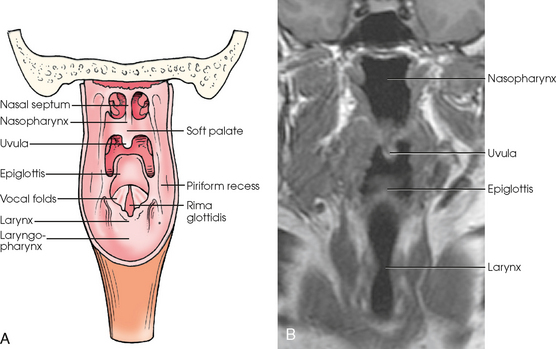

Fig. 15-1 A, Interior posterior view of neck. B, Coronal MRI of neck. (B, Courtesy J. Louis Rankin, BS, RT(R)(MR).)

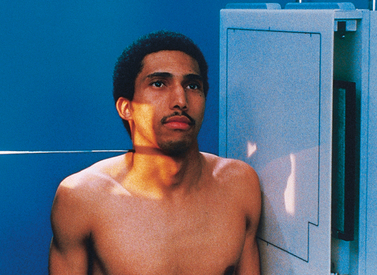

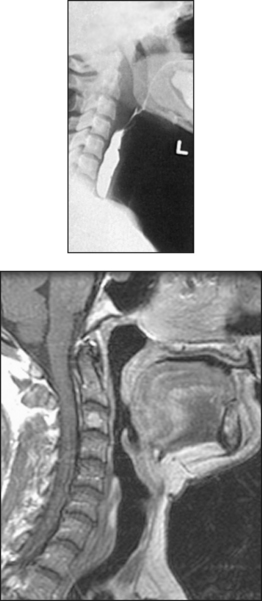

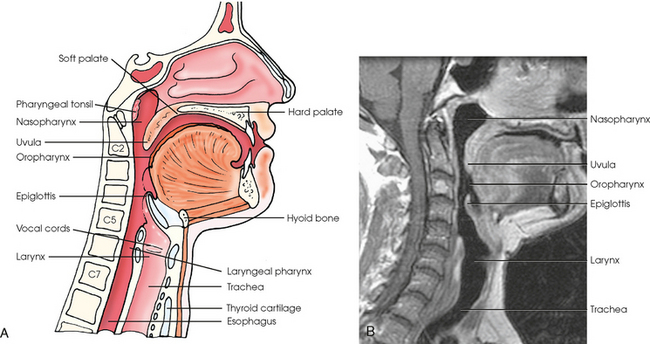

Fig. 15-2 A, Sagittal section of face and neck. B, Sagittal MRI of neck. (B, Courtesy J. Louis Rankin, BS, RT(R)(MR).)

The portion of the neck that lies in front of the vertebrae is composed largely of soft tissues. The upper parts of the respiratory and digestive systems are the principal structures. The thyroid and parathyroid glands and the larger part of the submandibular glands are also located in the anterior portion of the neck.

Thyroid Gland

The thyroid gland consists of two lateral lobes connected at their lower thirds by a narrow median portion called the isthmus (Fig. 15-3). The lobes are approximately 2 inches (5 cm) long, 1¼ inches (3.2 cm) wide, and ¾ inch (1.9 cm) thick. The isthmus lies at the front of the upper part of the trachea, and the lobes lie at the sides. The lobes reach from the lower third of the thyroid cartilage to the level of the first thoracic vertebra. Although the thyroid gland is normally suprasternal in position, it occasionally extends into the superior aperture of the thorax.

Parathyroid Glands

The parathyroid glands are small ovoid bodies, two on each side, superior and inferior. These glands are situated one above the other on the posterior aspect of the adjacent lobe of the thyroid gland.

Pharynx

The pharynx serves as a passage for air and food and is common to the respiratory and digestive systems (see Fig. 15-2). The pharynx is a musculomembranous, tubular structure situated in front of the vertebrae and behind the nose, mouth, and larynx. Approximately 5 inches (13 cm) in length, the pharynx extends from the undersurface of the body of the sphenoid bone and the basilar part of the occipital bone inferiorly to the level of the disk between the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae, where it becomes continuous with the esophagus. The pharyngeal cavity is subdivided into nasal, oral, and laryngeal portions.

The nasopharynx lies posteriorly above the soft and hard palates. (The upper part of the hard palate forms the floor of the nasopharynx.) Anteriorly, the nasopharynx communicates with the posterior apertures of the nose. Hanging from the posterior aspect of the soft palate is a small conical process, the uvula. On the roof and posterior wall of the nasopharynx, between the orifices of the auditory tubes, the mucosa contains a mass of lymphoid tissue known as the pharyngeal tonsil (or adenoids when enlarged). Hypertrophy of this tissue interferes with nasal breathing and is common in children. This condition is well shown in a lateral radiograph of the nasopharynx.

The oropharynx is the portion extending from the soft palate to the level of the hyoid bone. The base, or root, of the tongue forms the anterior wall of the oropharynx. The laryngeal pharynx lies posterior to the larynx, its anterior wall being formed by the posterior surface of the larynx. The laryngeal pharynx extends inferiorly and is continuous with the esophagus.

The air-containing nasal and oral pharynges are well visualized in lateral images except during the act of phonation, when the soft palate contracts and tends to obscure the nasal pharynx. An opaque medium is required to show the lumen of the laryngeal pharynx, although it can be distended with air during the Valsalva maneuver (an increase in intrathoracic pressure produced by forcible expiration effort against the closed glottis).

Larynx

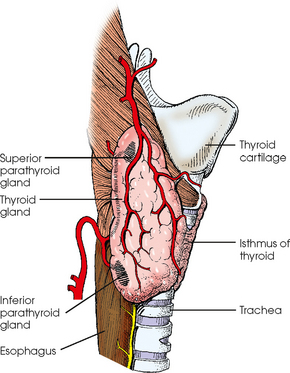

The larynx is the organ of voice (Figs. 15-4 and 15-5; see Figs. 15-1 through 15-3). Serving as the air passage between the pharynx and the trachea, the larynx is also one of the divisions of the respiratory system.

The larynx is a movable, tubular structure; is broader above than below; and is approximately 1½ inches (3.8 cm) in length. Situated below the root of the tongue and in front of the laryngeal pharynx, the larynx is suspended from the hyoid bone and extends from the level of the superior margin of the fourth cervical vertebra to its junction with the trachea at the level of the inferior margin of the sixth cervical vertebra. The thin, leaf-shaped epiglottis is situated behind the root of the tongue and the hyoid bone and above the laryngeal entrance. It has been stated that the epiglottis serves as a trap to prevent leakage into the larynx between acts of swallowing. The thyroid cartilage forms the laryngeal prominence, or Adam’s apple.

The inlet of the larynx is oblique, slanting posteriorly as it descends. A pouchlike fossa called the piriform recess is located on each side of the larynx and external to its orifice. The piriform recesses are well shown as triangular areas on frontal projections when insufflated with air (Valsalva maneuver) or when filled with an opaque medium.

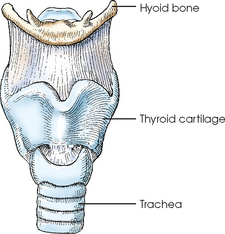

The entrance of the larynx is guarded superiorly and anteriorly by the epiglottis and laterally and posteriorly by folds of mucous membrane. These folds, which extend around the margin of the laryngeal inlet from their junction with the epiglottis, function as a sphincter during swallowing. The laryngeal cavity is subdivided into three compartments by two pairs of mucosal folds that extend anteroposteriorly from its lateral walls. The superior pair of folds are the vestibular folds, or false vocal cords. The space above them is called the laryngeal vestibule. The lower two folds are separated from each other by a median fissure called the rima glottidis. They are known as the vocal folds, or true vocal folds (see Fig. 15-5). The vocal cords are vocal ligaments that are covered by the vocal folds. The ligaments and the rima glottidis comprise the vocal apparatus of the larynx and are collectively referred to as the glottis.

Soft Palate, Pharynx, and Larynx: Methods of Examination

The throat structures may be examined with or without an opaque contrast medium. The technique employed depends on the abnormality being investigated. Computed tomography (CT) studies are often performed to show radiographically areas of the palate, pharynx, and larynx with little or no discomfort to the patient. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also used to evaluate the larynx. The radiologic modality selected is often determined by the institution and physician. The only radiologic examination currently performed to evaluate structures of the anterior neck is positive-contrast pharyngography.

POSITIVE-CONTRAST PHARYNGOGRAPHY

Opaque studies of the pharynx are made with an ingestible contrast medium, usually a thick, creamy mixture of water and barium sulfate. This examination is frequently done using fluoroscopy with spot-film images only. These or conventional projections are made during deglutition (swallowing).

Deglutition

The act of swallowing is performed by the rapid and highly coordinated action of many muscles. The following points are important in radiography of the pharynx and upper esophagus:

1. The middle area of the tongue becomes depressed to collect the mass, or bolus, of material to be swallowed.

2. The base of the tongue forms a central groove to accommodate the bolus and then moves superiorly and inferiorly along the roof of the mouth to propel the bolus into the pharynx.

3. Simultaneously with the posterior thrust of the tongue, the larynx moves anteriorly and superiorly under the root of the tongue, the sphincteric folds nearly closing the laryngeal inlet (orifice).

4. The epiglottis divides the passing bolus and drains the two portions laterally into the piriform recesses as it lowers over the laryngeal entrance.

The bolus is projected into the pharynx at the height of the anterior movement of the larynx (Figs. 15-6 to 15-8). Synchronizing a rapid exposure with the peak of the act is necessary.

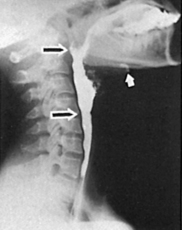

Fig. 15-6 Lateral projection with exposure made at peak of laryngeal elevation. Hyoid bone (white arrow) is almost at level of mandible. Pharynx (between large arrows) is completely distended with barium.

Fig. 15-7 AP projection of the same patient as in Fig. 15-6. Epiglottis divides bolus into two streams, filling the piriform recess below. Barium can also be seen entering upper esophagus.

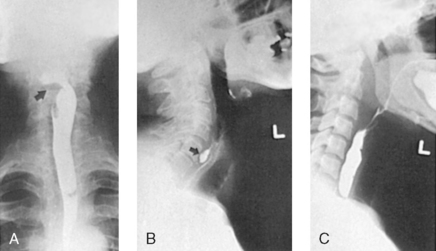

Fig. 15-8 AP projection of pharynx and upper esophagus with barium. A, Head was turned to right, with resultant asymmetric filling of pharynx. Bolus is passing through left piriform recess, leaving right side unfilled (arrow). B, Lateral projection after patient swallowed barium, showing diverticulum (arrow). C, Lateral projection made slightly later, showing only filling of upper esophagus.

The shortest exposure time possible must be used for studies made during deglutition. The steps are as follows:

• Ask the patient to hold the barium sulfate bolus in the mouth until signaled and then to swallow the bolus in one movement.

• If a mucosal study is to be attempted, ask the patient to refrain from swallowing again.

• Take the mucosal study during the modified Valsalva maneuver for doublecontrast delineation.

Some fluoroscopic equipment can expose 12 frames per second using the 100-mm or 105-mm cut or roll film. Many institutions with such equipment use it to spot-radiograph patients in rapid sequence during the act of swallowing. Another technique is to record the fluoroscopic image on videotape or cine film. The recorded image may be studied to identify abnormalities during the active progress of deglutition.

Gunson method

Gunson1 offered a practical suggestion for synchronizing the exposure with the height of the swallowing act in deglutition studies of the pharynx and superior esophagus. Gunson’s method consists of tying a dark-colored shoestring (metal tips removed) snugly around the patient’s throat above the thyroid cartilage (Fig. 15-9). Anterior and superior movements of the larynx are shown by the elevation of the shoestring as the thyroid cartilage moves anteriorly and immediately thereafter by the displacement of the shoestring as the cartilage passes superiorly.

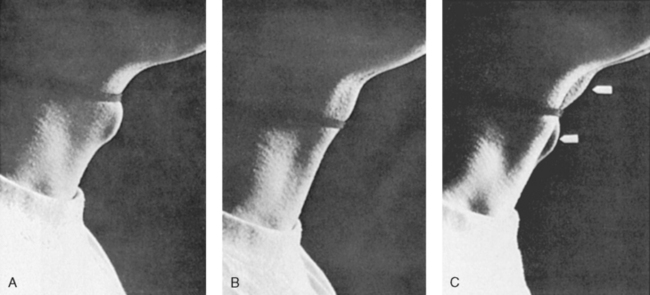

Fig. 15-9 A, An ordinary dark shoelace has been tied snugly around the patient’s neck above the Adam’s apple. B, Exposure was made at peak of superior and anterior movement of larynx during swallowing. Pharynx is completely filled with barium at this moment, which is the ideal instant for making an x-ray exposure. C, Double-exposure photograph emphasizing movement of Adam’s apple during swallowing. Note extent of anterior and superior excursion (arrows).

Having the exposure coincide with the peak of the anterior movement of the larynx—the instant at which the bolus of contrast material is projected into the pharynx—is desirable. As stated by Templeton and Kredel,2 the action is so rapid that satisfactory filling is usually obtained if the exposure is made as soon as anterior movement is noted.

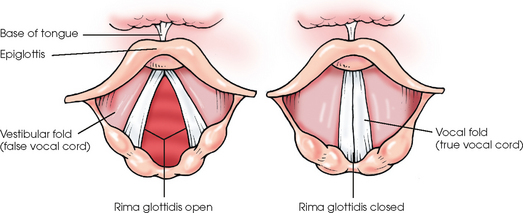

Pharynx and Larynx

Radiographic studies of the pharyngolaryngeal structures are made during breathing, phonation, stress maneuvers, and swallowing. To minimize the incidence of motion, the shortest possible exposure time must be used in the examinations. For the purpose of obtaining improved contrast on AP projections, use of a grid is recommended.

• Except for tomographic studies, which require a recumbent body position (Fig. 15-10), place the patient in the upright position, either seated or standing, whenever possible.

• Center the midsagittal plane of the body to the midline of the vertical grid device.

• Ask the patient to sit or stand straight. If the standing position is used, have the patient distribute the weight of the body equally on the feet.

• Adjust the patient’s shoulders to lie in the same horizontal plane to prevent rotation of the head and neck and resultant obliquity of the throat structures.

• Center the IR at the level of or just below the laryngeal prominence.

• Extend the patient’s head only enough to prevent the mandibular shadow from obscuring the laryngeal area.

• Respiration: Obtain preliminary radiographs (AP and lateral) during the inspiratory phase of quiet nasal breathing to ensure that the throat passages are filled with air. To determine the optimal time for the exposure, watch the breathing movements of the chest. Make the exposure just before the chest comes to rest at the end of one of its inspiratory expansions (Fig. 15-11).

Additional studies: Additional necessary studies of the pharynx and larynx are usually determined fluoroscopically. These studies may be made at the following times:

1. During the Valsalva or modified Valsalva stress maneuvers or both* (Fig. 15-12)

2. At the height of the act of swallowing a bolus of 1 tablespoon of creamy barium sulfate suspension. The patient holds the barium sulfate bolus in the mouth until signaled and then swallows it in one movement. The patient is asked to refrain from swallowing again if a double-contrast study is to be attempted.

3. During modified Valsalva maneuver, immediately after the barium swallow for double-contrast delineation of the piriform recesses

4. During phonation and with the larynx in the rest position after its opacification with an iodinated contrast medium

Tomographic studies of the larynx are made during phonation of a high-pitched e-e-e. After these studies, one or more sectional studies may be made at the selected level or levels with the larynx at rest (Fig. 15-13).

Soft Palate, Pharynx, and Larynx

R or L position

• Ask the patient to sit or stand straight, with the adjacent shoulder resting firmly against the stand for support.

• Adjust the body so that the midsagittal plane is parallel with the plane of the IR.

• Depress the shoulders as much as possible, and adjust them to lie in the same transverse plane. If necessary, have the patient clasp the hands in back to rotate the shoulders posteriorly.

• Extend the patient’s head slightly.

• Immobilize the head by having the patient look at an object in line with the visual axis.

• Perpendicular to the IR, centering the IR (1) 1 inch (2.5 cm) below the level of the EAMs to show the nasopharynx and to perform cleft palate studies; (2) at the level of the mandibular angles to show the oropharynx; or (3) at the level of the laryngeal prominence to show the larynx, laryngeal pharynx, and upper end of the esophagus (Fig. 15-14).

Procedure: Preliminary studies of the pharyngolaryngeal structures are made during the inhalation phase of quiet nasal breathing to ensure filling of the passages with air (Fig. 15-15).

According to the site and nature of the abnormality, further studies may be made. Each of the selected maneuvers must be explained to the patient and practiced just before actual use. The studies are obtained at one or more of the following:

1. During phonation of specified vowel sounds to show the vocal cords and to perform cleft palate studies (Fig. 15-16)

2. During Valsalva maneuver to distend the subglottic larynx and trachea with air (Fig. 15-17)

3. During modified Valsalva maneuver to distend the supraglottic larynx and the laryngeal pharynx with air

4. At the height of the act of swallowing a bolus of 1 tablespoon of creamy barium sulfate suspension to show the pharyngeal structures

5. With the larynx at rest or during phonation after opacification of the structure with an iodinated medium

6. During the act of swallowing a tuft or pledget of cotton (or food) saturated with a barium sulfate suspension to show nonopaque foreign bodies located in the pharynx or upper esophagus

1Gunson EF: Radiography of the pharynx and upper esophagus: shoestring method, Xray Tech 33:1, 1961.

2Templeton FE, Kredel RA: The cricopharyngeal sphincter, Laryngoscope 53:1, 1943.

*The Valsalva maneuver is performed by forcible exhalation against a closed airway, usually by closing the mouth and pinching the nose shut. The modified Valsalva maneuver is performed by forcible exhalation against a closed glottis.