The Human-Animal Bond, Bereavement, and Euthanasia

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Discuss the aspects of strong attachments to animals.

2 List and describe the stages of grief and the role of veterinary professionals in grief counseling.

3 Discuss the impact of euthanasia and client grief on members of the veterinary health care team.

4 Discuss the legal and ethical issues related to euthanasia.

5 Describe the factors that owners consider when making decisions regarding euthanasia of their pet.

6 Discuss the role of the veterinary health care team in counseling owners considering euthanasia of their pet.

7 Describe considerations in scheduling euthanasia appointments and when preparing for unexpected events during euthanasia.

8 List and describe acceptable methods of euthanasia in animals.

9 List signs and symptoms of staff burnout.

10 Discuss special considerations related to euthanasia of large animals.

THE HUMAN-ANIMAL BOND

Today modern society is largely urban rather than rural. Through world urbanization, people tend to live in neighborhoods rather than on farms. Animals live with their owners in apartments or houses, thus increasing familiarity, dependency, and bonding. Eighty percent of our animal companions live inside.

Companion animals provide both parents and children with stability, constancy, and security. It is not unusual for families to change locales and residences several times within a 10-year period. As a result, most people no longer live within a short distance of their extended families. The nuclear family is smaller, consisting of an average of less than two children. The single-parent family is becoming common. Because an increasing number of U.S. women work outside the home, many school-age children return home to be greeted not by their mother but by the family pet. An increasing number of adults live alone, and couples opt to remain childless. More and more people are filling these voids with pets that provide a unique outlet for their owners’ needs to nurture and be loved. As health and medical care improves, the number of persons in the age group older than 60 years has increased to more than 16% of the population. Pets fulfill many needs for elderly people, including needs for interaction, exercise, companionship, protection, and motivation to remain active and independent.

It is becoming increasingly recognized that physically and mentally disabled individuals benefit from contact with animals. As society has realized the special talents of pets, new utilitarian functions have been found for them. Dogs are used with success to assist blind, hearing impaired, and physically challenged persons. These specially trained animals provide their owners with independence, companionship, social lubrication, protection, and love. Horses, cats, and dogs have been used successfully in animal-assisted therapy programs for people with all types of physical and mental disabilities. Animals facilitate interaction with people who may be reluctant to interact, and their presence reduces anxiety, lowers blood pressure, and decreases heart rate. Results of some studies indicate that animals may alleviate or prevent depression. Survival rates for cardiac patients who are pet owners are higher than for those who do not own pets. Pet ownership is considered an important predictor of survival for patients with coronary artery disease.

In short, the relationships between people and animals have become physically closer, and the role of animals in the daily lives of their owners has become more emotional as society has changed. Of the more than 71.1 million families owning at least one pet, one third of companion animal pet owners describe their pets as family members and cite companionship, love, affection, and fun as the most important derivatives of the relationship. Further, it has been shown that 83% of pet owners refer to themselves as mom or dad; 93% buy their pet gifts; 84% treat them as children; and 63% say, “I love you” at least once daily to their pets.

THE ATTACHMENT BETWEEN ANIMALS AND HUMANS

Strong attachments can form between owners and any type of animal, but are probably recognized most commonly in veterinary practice with dogs, cats, and horses. The degree of attachment varies greatly from the utilitarian attachment between a rancher and his or her cattle to the parent-child type of bonding that occurs between some people and their dog or cat. In 2007, 63% of the 133.7 million households in the United States own at least one pet. It is estimated that about 50% of these pet owners classify their attachment to their pet as strong. Of these “strong attachment” owners, about half see their pets as reflections of themselves or of their tastes that depend on the owner for love, affection, and care. The other half of the strong attachment owners report a reliance on their pets as an emotional crutch, supplying unconditional love and affection and sometimes acting as a substitute for family, friends, or children.

As pets are used to meet many of the changing psychosocial needs of modern society, the intensity of attachment has increased. When pet loss occurs, intensity and duration of attachment determine the significance of the loss and intensity of grief that follows. Attachment is more intense when the animal has functioned in many roles for the owner. The owner of an assistance dog may therefore suffer more intense bereavement than the owner of a dog used only for herding or hunting. Owners who have experienced previous significant losses, adjustments, or traumas and have been comforted by their pet’s presence may also exhibit strong attachment and thus intense bereavement.

BENEFITS OF ATTACHMENT

As reminders of both pleasant and traumatic events in people’s lives, pets can take on symbolic meaning. There are several keys that are helpful in assessing the level of attachment between an owner and his or her animal or animals (Box 38-1). Even when the pet is simply another family member, grief can be intense. Grief is also individual, and each family member may grieve in a unique way.

PET LOSS AND VETERINARY MEDICINE

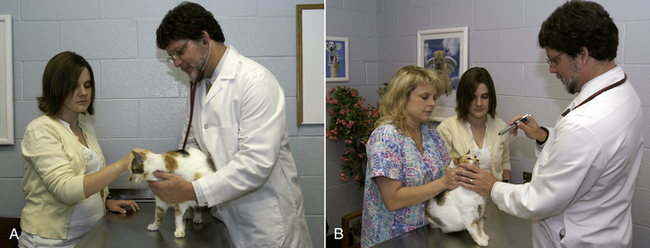

Veterinarians and veterinary technicians are confronted daily with complex issues of attachment, loss, and grief in the course of their patients’ illness and death. The diagnosis of life-threatening or terminal disease can be a difficult time for both the client and the veterinary professional (see Figure 38-1).

Considering all the emotional and utilitarian aspects of the human-animal relationship in modern society, it is not surprising that the breaking of the bond because of the death of the pet is a significant event in the lives of many pet owners. The loss of the pet for many owners is made even more intense and personal in that the pet is often grieved by no one other than themselves. Daily routines are filled with reminders of activities once performed for or with the pet. The loss of a pet often means that a unique, irreplaceable member of the family is gone.

A person’s support system is made up of people (and pets) that interact with one another on a daily basis, providing support, comfort, and social interaction. Support systems are especially important during times of loss. Unfortunately, many people who make up these support systems do not understand the full extent of attachment between a pet owner and pet. This lack of understanding can present serious problems for the owner facing the odyssey of grief after the death of a pet. As a result, pet owners often turn to veterinary professionals as sources of support, comfort, and understanding at and around the time of their pet’s death.

The tendency for people to turn to the veterinary staff during the period of grieving the death of a pet places veterinary professionals in an awkward position. It demands that they have knowledge that is typically outside the boundaries of traditional veterinary medicine and requires that they find a comfort level in talking about death and the grief process. This is why the areas of attachment, animal behavior, human bereavement, and grief counseling are becoming increasingly relevant to veterinary medicine.

WHEN THE BOND IS BROKEN

In general, people in U.S. society are uncomfortable talking about death. We know little about the experience of death, and we fear the unknown, yet veterinarians and their staff must frequently discuss death, participate in causing it, witness it, and deal with the emotions triggered by these experiences.

Although people in the midst of grief have a need and a right to understand what is happening to them, there are few places that they can go to get helpful, supportive information about grief. This is particularly true when the loss that they are grieving is that of a beloved pet. Like most of society, veterinarians and veterinary technicians rarely have formal training in this area. Despite this fact, veterinary professionals are still often the people clients instinctively turn to for support.

Making the job more difficult is the fact that grief and bereavement are emotional and often irrational areas of human interaction. Bereaved individuals may at times seem out of control or out of touch with reality. When this happens, those around the griever, including the veterinary professional, may feel uncomfortable; few veterinary professionals are taught how to support or deal with people who are irrational or emotional. Compassion is an important sensitivity to draw on when interacting with clients experiencing grief.

Grief is the companion to death. It is the mental anguish experienced by any human confronted with the loss of an object of attachment. Grief may ensue as an effect of any loss; the loss may be through death, divorce, loss of a job, or even moving or having friends move away. It can be intensely emotional and can affect mind, body, and spirit. When confronted with grief, the bereaved individual goes through a grief process. The term grief process implies that there is an intended end or result to be produced through grieving. Thus the grief process is the means of letting go of the object of attachment to feel better, reinvest, emotionally grow, and attach again.

The veterinary staff is in a unique position to assist clients going through the process of grief as it relates to the loss of a pet. By way of their unique role in the life of both the owner and pet, veterinary professionals are in a unique position to understand the bond that had developed. In addition, the veterinarian and the owner may have interacted uniquely in choosing the time of the pet’s death (as occurs when euthanasia is performed). To assist clients during the difficult bereavement period, it is helpful to understand the normal grief process and its manifestations as applied to pet loss.

PET LOSS AND THE GRIEF PROCESS

The death of a pet is all too often regarded as a trivial loss by society perhaps in part because of the mistaken belief that pets can be easily replaced. There are no socially sanctioned rituals, such as funerals or memorial services, to help grieving pet owners gain support once the bonds between them and their animals have been broken. Further, people are rarely granted time off from their jobs to care for sick animals or to make arrangements for them after their deaths. Society also does not allow adequate time for mourning the death of a pet. Most people feel pressured to be “back to normal” within a few days of their pet’s death to avoid being labeled as neurotic, hysteric, or overly attached. However, crying, taking time away from work, and wanting to memorialize a pet are healthy responses to the death of a pet. They should not be discouraged, nor should they be judged.

One of the most effective ways for veterinary professionals to assist grieving clients is to educate and reassure them that their feelings and behaviors are normal parts of the grief process. Other ways that veterinary professionals can help are listed in Box 38-2.

THE NORMAL GRIEF PROCESS

As stated earlier, the word process implies movement toward some end or result. In regard to grief, this movement is accomplished by passing through what have been termed stages, phases, or tasks. Although there are a few differences, the basic emotional process in pet loss is the same as in human loss.

Several models of the grief process can be modified to describe the emotional process that occurs during pet loss. The following discussion uses the classic model supplied by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (see Recommended Reading).

Dr. Kübler-Ross was one of the first to work extensively with dying persons and their families during the late 1960s. She described the grief process as consisting of five stages: denial, bargaining, anger, depression, and resolution. She used the stages to describe the passage through grief, but it is helpful to remember that these stages are not a linear odyssey. Although people may travel through the grief process in a straight line, they more often fluctuate between stages, bounce back and forth, and feel the entire gamut of grief within minutes, days, or months.

Denial and Bargaining

Denial is a normal defense mechanism that buffers humans from some unbearable news or reality. It is important to recognize the word normal here because many individuals experiencing denial at the time a poor prognosis is given or during bereavement will seem to all observers to be out of touch with reality. The veterinary staff may wonder whether

the client has even heard the veterinarian stating the seriousness of an animal’s illness. A client in denial may listen attentively to a diagnosis of cancer with a poor prognosis, but ask only if the toenails can be clipped or if their current flea shampoo is correct. A client informed of the death of his or her pet while it was hospitalized may chatter on about activities for the weekend. A simple form of denial is exemplified by the client who states repeatedly, “It can’t be. I don’t believe it.”

It is tempting when presented with a client experiencing denial to insist that he or she recognize the seriousness of the situation. Many veterinarians and veterinary technicians worry that the client does not comprehend or has not heard correctly. There is no harm in repeating oneself to a client in denial (Figure 38-2). Restating diagnoses, prognoses, treatment plans, and particulars is advisable. However, clients in denial will accept the unbearable reality of the situation only when they are ready internally; attempts to push them may backfire, resulting in frustration. Usually a client will begin to ask appropriate questions about the time he or she arrives home and may telephone the veterinary office. Some may even seem to return to reality before your eyes while those toenails are attended to. The veterinary professional must be assured that the client has been told the basic information that needs to be given. Remember, however, that it may not have been fully understood; therefore always leave the door open for further communication.

FIGURE 38-2 Even when dealing with attentive clients, veterinary professionals may be required to repeat themselves several times while clients decide on a course of treatment for their pet. Clients overwhelmed with emotion may have difficulty comprehending information regarding treatment or euthanasia decisions. Members of the team must be patient.

Denial is reflected by the client’s eyes and demeanor and by incongruous questions. The veterinary staff should not believe that they are responsible to “break through” a client’s denial. The client will move out of denial, accepting the reality of the situation, when he or she is ready. The veterinary staff’s recognition of the client’s denial can prevent impatience and frustration during the veterinary contact.

Once the reality of death or impending death is realized, the client may show various impotent attempts to control or to reverse the reality. The client is grappling with the stage of the grief process that Dr. Kübler-Ross called bargaining. During this stage, the client maneuvers personally and privately, possibly praying and negotiating with God for miracles. The client might add various herbs and old family remedies to food. Children behave like little angels, hoping to be rewarded with a reversal of bad news. The veterinary staff may be subject to various inquiries by the client at this stage, relative to the latest “miracle cure” that the client has discovered on the Internet. It is while bargaining that a pet owner may also request permission to obtain a second (and sometimes third, fourth, or fifth) opinion. During this time be compassionate, and when possible answer clients’ questions. Help clients to understand that this stage of grief is normal.

Seeking to replace the lost animal without grieving at all is a form of bargaining. Many pet owners seek a new pet too soon, and they purchase the same species, the same color, and name them the same or a similar name.

It is important to recognize denial and bargaining as part of the normal grief process. Veterinary professionals who understand these stages will avoid frustration in their attempts to provide quality patient care and client service.

Anger

During the grief process, clients may move in and out of the stage called anger. Clients coping with this stage may exhibit anger in a wide variety of direct or indirect manners. The anger may be specific or nonspecific in the way that it is directed. Anger may also be exhibited in the form of guilt, which can be defined as anger turned inward.

Anger is a particularly difficult emotion to deal with when a client directs it toward the veterinary professional. Regardless of whether or not the client is justified in his or her stated cause for anger, staff members must use tolerance and patience to avoid responding defensively. Bereaved clients may complain that the illness that resulted in death should have been discovered sooner, should have been treated differently, or should not have been allowed to happen. They may complain that their pet died while hospitalized because of neglect or inappropriate treatment rather than because of the tumor revealed by necropsy.

Anger may be apparent in the form of guilt. Clients feeling guilt use language with an abundance of “I should’ve” statements. They often seek the listening ear of the veterinary professional looking for absolution from guilt. They may ask whether the food that they fed their pet could have contributed to the illness or death. They often ask whether it was the pesticide in their home or in the shampoo that caused a tumor or cardiac arrest. Clients may believe that they allowed their pet to be too active or too fat; others may believe that they caused the kidney failure in their cat by feeding an insufficient diet. These clients can direct anger at themselves, but frequently they cannot find a specific crime that they committed. When possible, the veterinary professional can assist the clients by assuaging their guilt. Reassuring clients that, in your opinion, they did everything possible for their pet, that they did only what they thought would benefit their pet, and that they made the right decisions for their pet will relieve much of the clients’ guilt or anger and assist them in moving through the grief process.

The client in this stage may be gruff or rude and generally hard to get along with. Stating that he or she is angry, the client may be at a loss to express the object of the anger. These clients may yell at the cashiers, the hospital manager, the receptionist, the technicians, and the veterinarian. Giving the angry client an opportunity to express feelings (venting) is an effective way for the veterinary professional to help. At times, all that is needed is for the sensitive veterinary professional to explain that considering the client’s loss, anger is a normal feeling.

Anger is often exhibited by reluctance to pay the bill. On receiving an inquiry by telephone, the client implies that nonpayment is due to anger at treatment by the veterinarian or technician, the pet was neglected, the illness was mistreated, or the client was treated insensitively. Bereavement support can alleviate this client’s anger. Listen attentively, state your apologies, if any, and follow up with this client. No admission of mistakes need be made, but the client needs to feel significant and understood.

Anger is difficult to work through, but it is guilt that may be hardest for the client to relinquish. In continuing to feel guilt and anger, the client avoids letting go of the beloved pet, and the grief process is stymied. Once the client is able to relinquish the guilt or anger, the grief process can continue.

The veterinary professional can assist the client with all types of exhibited anger by taking a mental step back and a deep breath, committing to a nondefensive attitude, and simply listening. Take notes, if possible, and reassure the client of follow-up if anger is directed at veterinary staff. Assuage any guilt if the opportunity arises and allow the client to vent. A few minutes on the telephone or in person may salvage a client relationship and go a long way in assisting the client through the grief process.

Depression

The stage of the grief process that is termed depression has also been called grief. Clients experiencing depression describe their mood as complete, overwhelming sadness. Intense grief can result in depression, which prohibits a client from functioning normally. Appetite is changed, energy level is lowered, the client withdraws from others, and sometimes the client is unable to go to work. More subtle symptoms of depression include irritability, sleep irregularity, restlessness, and inability to concentrate.

The veterinary professional has occasion to recognize depression as a result of pet loss when follow-up contacts are made with the client. Depression, when severe, usually sets in some time after the loss. Clients with poor social support systems, elderly clients, and clients with intense or symbolic attachment to the pet may experience worrisome depression.

When contacts are made several days or weeks after bereavement and it is suspected that a client is depressed, referral can be made to a counselor or hot line specializing in pet loss (Box 38-3). Although referral sometimes is awkward, it might be gently phrased as, “I know a person experienced in counseling people who have lost their pets.” Reassurance that grief is normal is beneficial.

Most clients feel overwhelmed by their emotions because of grief. They describe feeling as if their emotions are out of control. They may also state surprise and worry that they are reacting with such intensity to the death of an animal. They may be embarrassed. It comforts clients when veterinary professionals confide that most pet owners feel and act similarly after the loss of a pet. Assuring them of your knowledge of their pet’s importance and your respect for their grief is valuable to them.

Grief must be worked through, not avoided; thus it is a process requiring some emotional catharsis. Many clients cry, and some are uninhibited about expressing anger and sadness. Becoming comfortable with one’s own emotions facilitates comfort with others’ emotions. It is human and necessary to feel empathy for grieving clients, but it can also be uncomfortable and painful. Separating your own feelings from theirs will allow you to transform empathy into sympathetic gestures that help the client.

Resolution or Acceptance

The stage of resolution or acceptance is the belief that everything is OK, normal functioning is restored, and emotional energy is reinvested. This does not mean that the pet is forgotten but that it has been assigned to a special place in the bereaved individual’s heart. New attachments can be made without regret and hesitation. Resolution may come easily for some and may be difficult for others. In general, children reach the stage of acceptance and resolution more quickly and more easily than do adults. (For more information on how to help children when a pet dies, see Box 38-4.) As stated previously, the grief process is not linear, and bits of this stage occur with more and more frequency and with longer durations throughout the grief process. Eventually the client who successfully resolves the grief process experiences little, if any, of the first four stages.

There are many factors that may complicate the grief process (Box 38-5). These complicating factors may lengthen the time it takes to reach resolution or in severe cases may arrest progress through the grief process without allowing the individual to reach a resolution. Situations in which the grief process is complicated may not affect some individuals’ ability to progress, but may drastically affect that of others. Few veterinary professionals are equipped to give the special kind of help that these complicated situations may require, but most have empathy and the ability to listen for signs that indicate someone may need help. Early recognition of factors that may complicate the grief process can be helpful when a person appears not to be progressing well through the process. Early recognition may also be important for timely referral in situations in which further assistance is required. Keeping on hand a list of professional alternatives for referral to someone who can give the help that is needed is advised (see Box 38-3 for a short list of potential sources of help).

The question is often raised whether clients should get a new pet before they reach resolution of the grief process (Figure 38-3). The process itself is highly variable in length. It can be as short as a few weeks to as long as many years. Most pet owners are able to reinvest and reattach to a new pet at any time, but only after they become aware that replacement of their unique loved one is impossible. If companionship, tactile closeness, and friendship are desired while grieving, these qualities can be obtained through a new pet. Cautioning and encouraging clients to choose animals somewhat dissimilar to their dead pet can be helpful. Having a new pet forced on the grieving individual who is not ready to reinvest in a new relationship will only end up furthering heartache in the bereaved and causing unhappiness in the new pet.

GRIEF AND THE VETERINARY PROFESSIONAL

Individuals in the veterinary profession deal with client grief on an almost daily basis. Rarely do they think about their own. The veterinary professional must realize the grief process that the client is struggling with is not taking place in an emotional vacuum. It is real and touches not only the bereaved person, but also those around him or her, including the veterinary professional. It is common for veterinarians and veterinary technicians to cry with clients, to feel a lump in the throat, and to feel guilty or depressed or experience a sense of failure. The fact that veterinary professionals may go through a grief process each time a patient is lost must be recognized and accepted. Time should be spent thinking about these feelings and responses. Validation of the process within the profession, by way of staff meetings, discussions, and support sessions, can be important in recognizing and dealing with the stresses of “professional grief.” Left unacknowledged, the grief process encountered by veterinary professionals can become destructive and lead to burnout.

EUTHANASIA

Perhaps no single issue in veterinary medicine conjures up the range of emotion, ethical deliberation, and stress occasioned by euthanasia. Euthanasia was defined by the 2001 American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) panel on euthanasia as “the act of inducing painless death,” but the act is only one small aspect of the larger issue facing the profession.

The word euthanasia is derived from the Greek root eu, meaning good, and thanatos, referring to death. Few in the veterinary profession would argue that when used in the context of relieving suffering, the word runs counter to its Greek roots; however, as the word is currently defined, it also pertains to the killing of unwanted, abandoned, stray, or phenotypically undesired animals by veterinary professionals. It is not always in the common interest of the patient, client, and veterinarian that euthanasia is performed, and in this way, problems can arise in balancing conflicting interests. Euthanasia is an emotionally charged issue, with members of the profession varying significantly in their acceptance of the practice and in their views as to its utility. On the one hand, it might be viewed simply as “convenience killing,” whereas on the other, it might be viewed as a means of furthering respect and love through the compassionate termination of hopeless suffering. No matter how one looks at it, the animal health professional may be caught in the middle, experiencing doubts, confusion, and moral questions over participation in the ending of an animal’s life. It is an ethical dilemma that does not have an easy or even an absolutely right or wrong answer. It is an issue that all veterinary professionals must wrestle with, individually and collectively.

THE DECISION

The decision to perform euthanasia is one of the most difficult decisions that the owner of a companion animal will ever face. Some owners may make the decision quickly because of financial constraints or fear of what the illness may eventually cause, whereas others may never be able to make the decision, preferring to let their pet die naturally. The decision is often made more difficult because few pet owners have an adequate support group available that understands the bond that develops between an animal and the recipient of its unconditional love.

Most owners who elect to have euthanasia performed make the decision because they perceive that their pet’s illness involves some degree of suffering. Suffering is difficult to define, and perceptions of animal suffering differ greatly between individuals and from case to case. The place the pet holds in the owner’s family circle, how long the pet has been owned, the relationship between the pet and other loved ones, the financial resources available to the owner, and the disease process afflicting the pet are other factors that most owners take into consideration when trying to make the decision.

The veterinary team (veterinarian, veterinary technician, animal health care providers) can play an important role in the decision-making process. The veterinary staff often serves as a sounding board for the client who is trying to make the decision. Staff members can help with the decision by approaching the subject professionally with compassion and respect. The most important help that the team can give is to provide information. What the owner can expect from the disease process, what treatments are available, the prognosis with and without treatment, and what costs are involved are all questions that should be answered by the veterinarian. The veterinary technician can play a vital role as a client resource by answering questions about euthanasia. How euthanasia is performed, whether the animal will feel pain, how long the procedure will take, and what happens to the body afterward are all areas that a technician may be asked to address.

When interacting with an owner considering euthanasia, the veterinary professional should go to great lengths to lay out all options available while being careful not to make the decision for the client. Too many veterinary professionals make judgments as to the value of an animal (both monetary and personal) that only the owner can make. Questions such as “What would you do if he were your animal?” are difficult to address and perhaps best answered by urging the client to verbalize what he or she sees as the pros and cons of each choice. In doing this, it may become obvious that the client has already made the decision and is looking for support or validation. The client may feel guilt, anger, sadness, depression, pain, and helplessness during the decision-making process and after euthanasia has been performed. The veterinary professional can help by assuring owners that these feelings are normal and indeed expected and by assuring them that they are not alone in the pain that they are feeling.

Once an informed decision has been made, it should be supported, even if it may not have been the decision that the veterinarian or veterinary staff would have made. Pet owners are sensitive to the actions of hospital personnel, and for this reason, it is extremely important that persons interacting with the client or handling the animal in the presence of the owner be supportive, gentle, and empathetic.

At times, decisions concerning euthanasia may be made based on convenience factors. Convenience euthanasia for reasons such as a client moving and not being able to take the animal, new furniture in the house, or an inability to effectively house train an animal is something that most veterinary professionals will have to face. It is up to each practice to decide how they are going to deal with these issues. Some practices will decide that they are going to follow the owner’s wishes no matter what, and others will decide that they are not going to euthanize animals in these settings. Often situations are looked at on a case-by-case basis, and although this may result in an inconsistent approach, it may be best, especially if all members of the practice understand how decisions are made. Questioning a client concerning their reasons for choosing euthanasia in these situations will sometimes bring out that they are making the decision because they really do not know that there are other options. Education about what other options are available will sometimes result in a happier outcome.

AS THE END DRAWS NEAR: THE BEGINNING OF THE END

The death of a pet can be a devastating experience that can drastically affect the relationship between client and veterinarian. As many as 40% of clients change veterinarians after a pet has died. This number probably approaches 100% if euthanasia is handled in a manner that causes the client to perceive a lack of care, concern, or respect on the part of the veterinarian or other staff members. On the other hand, much can be done to foster a long-lasting relationship through the professional and compassionate handling of euthanasia. It is often true that the client who loudly sings the praises of a veterinarian and staff is not the owner of an animal saved through long hours of hard work and outstanding medical care, but rather the owner who was treated with compassion, care, and concern at and around the time of the loss of a pet.

Preparations for pet loss should begin as soon as it becomes apparent that death is a possibility. The veterinarian should discuss euthanasia with a client early so that the client understands that it is an available option. However, it is important to discuss all other medical or surgical options first. Euthanasia should not be presented in such a manner that it is either completely discounted or viewed as the only reasonable course. Remember that the initial reaction of a client receiving bad news is often denial or feelings of numbness or shock. It is important to allow time for this initial reaction to fade and for the entire family to be given time to discuss the various options before allowing the client to make such a difficult and important decision.

While discussing options with the client, the veterinarian should not use alternative jargon for euthanasia, such as put to sleep, put down, put away, humanely destroy, rock, and shoot, unless its meaning is understood by all individuals involved. Confusion will result from the use of a term such as put to sleep when talking to a companion animal owner who perceives the phrase to refer to anesthesia instead of euthanasia. Children are especially confused by the term put to sleep and may associate death with sleeping causing them to be afraid that they might die when going to sleep at night. Whatever term is used to describe the act of euthanasia, it is important that it be fully understood by all parties involved.

Once the decision has been made to have an animal undergo euthanasia, a client must make many decisions. When and where should the euthanasia take place? Should the client or other family members be present during the euthanasia? What is to happen to the body after euthanasia? Should a necropsy examination be allowed? What special method, if any, will the client use to memorialize the pet? It is best to discuss these concerns thoroughly in advance so that everyone understands precisely the wishes of the client.

The client together with the veterinarian should decide who will be present during the euthanasia. This is sometimes a difficult decision for both the client and the veterinarian. Some veterinarians do not offer this option to the client in the mistaken view that it will be too difficult for the client to watch. Contrary to this view, many clients will grieve more easily and accept more quickly the loss of their pet if they have had the opportunity to say goodbye in this most personal way (Figure 38-4). The chance to hold their pet and let it know that it is loved dearly while sharing its last moments is sometimes an important first step in the grief process. However, with the benefits to the client can come problems for the veterinarian and staff. Veterinary team members must realize that having the client present can increase their own stress level associated with euthanasia, and every attempt should be made to understand and minimize its effects.

FIGURE 38-4 Clients’ presence during the euthanasia of their companion animal helps them to say goodbye. Allow the client to make as many decisions, with guidance, about the site, time, and tempo of the euthanasia process; this makes the event more personal and meaningful.

When the client or family members are to be present, euthanasia should be scheduled for a time of day when interruptions are unlikely, the waiting room is empty, and the potential for embarrassment by public exposure is minimized. Early mornings, evenings, or during the lunch hour may be suitable. It is best to schedule at least 30 minutes. The most important aspect of the euthanasia to consider is communication. The unexpected should be avoided at all costs, and before the procedure, the client should be given a detailed explanation of exactly what is about to happen to the pet and what he or she is about to see. Then the client should be talked through each step of the procedure. The euthanasia should proceed at a pace with which the client feels comfortable. Occasionally, pets will urinate, defecate, vocalize, twitch, or gasp after they have become unconscious. Although these reflex acts can be minimized, they will still occasionally occur and will have a far less negative effect if they are expected and if the client is told that they are not a reflection of pain or suffering.

It is important for the veterinary team to effectively recognize signs of pain, fear, and distress so that they might be minimized either related to the disease process or during euthanasia. Distress vocalization, struggling, attempts to escape, aggression, panting, salivation, urination, expression of anal sacs, tremoring, tachycardia, and dilation of the pupils may all indicate distress, pain, or fear. Awareness of these signs can help to minimize stress during the euthanasia process.

Deciding where the euthanasia is to take place can be important. Using a hospital space that is less stark than the typical stainless steel hospital examination room is preferred. If the examination room is to be used, at least a blanket should be placed over the table and there should be a chair where the client can sit down. Some clients will request that the euthanasia be performed at home or at some special place. Many veterinarians will honor these requests or use the services of a house call practice for this need. Sometimes just to be outside the “normal” environment of the veterinary facility is a fair and acceptable compromise. A blanket on the floor, the lawn beside the practice, and even the back seat of the family car might serve this purpose. One important consideration for the veterinarian in choosing the place is that many clients will feel uncomfortable coming back into the room where a pet previously underwent euthanasia. Indeed, many clients switch veterinarians because of a lack of sensitivity to this fact by the veterinary staff. To minimize this potential conflict in the future, it is best to choose a space that will not be routinely used for other client-related activities.

Clients who choose not to be present during euthanasia may still wish to see the body of the animal after it is dead. Seeing the animal dead conveys finality and also allows the client the opportunity to say goodbye. Many clients have a difficult time proceeding through the grief process if they have not been given this chance.

Make arrangements in advance concerning how payment for services is to occur. Discuss with the client whether payment is going to be made in advance, at the time of services, or by a later bill. This can be an uncomfortable subject to broach after euthanasia has occurred.

AT THE END

Once all the preparations have been made, the euthanasia should be performed with skill and concern. Each member of the veterinary team should be well trained, know his or her responsibilities, and be available. The key, as already mentioned, is to expect and plan for the unexpected. Although many methods of euthanasia are deemed acceptable by the AVMA panel on euthanasia, only those that are aesthetically acceptable should be used when the client is going to be present.

If the examination room is to be used, the table should be covered with a cloth or blanket. Some owners will want to bring a favorite blanket for the pet to spend its last few moments on. It is important that they understand that it is possible, indeed likely, that the blanket will be soiled by feces or urine when euthanasia occurs. If the pet is likely to be aggressive or extremely apprehensive, sedating it ahead of time should be considered. If the client is to be present, the animal should be taken away briefly so that a peripheral vein can be catheterized for smooth delivery of the euthanasia solution. It is advisable to put the catheter into a vein in a back leg; this will allow the client to hold the animal and pet its head without getting in the way of the veterinarian while the injections are given. Once the catheter has been placed, the client should be given the opportunity to be alone with the pet for a few moments.

Before administering the euthanasia solution, a saline solution should be injected into the catheter to ensure its patency. Next the patient should be anesthetized with propofol or an ultrashort-acting barbiturate. This will decrease the incidence of excitement after the euthanasia solution is injected. Once the animal is anesthetized, the euthanasia solution can be injected. Sodium pentobarbital is the most commonly used euthanasia solution. It is a member of the barbiturate family of drugs that depress the entire central nervous system.∗ When large doses of this drug are administered, as for euthanasia, unconsciousness occurs first, and then breathing stops because of depression of the respiratory center. This is followed by cardiac arrest. The pentobarbital dose, concentration, and rate of administration determine the speed of action. When the drug is administered intravenously, animals die swiftly and quietly. Although intravenous administration is preferred, the drug is also effective when injected intrahepatically, intracardiac, and, to a lesser extent, into the peritoneal cavity. Intracardiac and intrahepatic injection, although effective, is not considered appropriate for euthanasia of awake animals because it can be difficult to accurately inject euthanasia solutions into these organs consistently. Intraperitoneal injection of nonirritating solutions is considered appropriate in situations where intravenous injection is not possible. Death following intraperitoneal injection may take as long as 15 minutes, however, because of relatively slow absorption. Pentobarbital for euthanasia is available alone or in combination with other drugs. The concentration of pentobarbital in most euthanasia solutions is approximately 20% by weight. The recommended dose is 2 ml for the first 4.5 kg of body weight and 1 ml for each additional 4.5 kg of body weight. Sodium pentobarbital should be administered as rapidly as possible to provide the quietest and swiftest form of euthanasia. The veterinary team should be completely familiar with the use of the euthanasia solution chosen and the possible reactions that might be seen.

Because the cerebral cortex is affected by general anesthetic, predominant emotions may take over and the animal may show fear behavior, which is usually characterized by struggling and vocalization. Experimental studies indicate that the animal is not conscious of these feelings at the time. People who have undergone the “excitement” phase during general anesthesia do not remember that it took place. Although trained individuals may understand this excitement phase from the clinical standpoint, it is difficult for the owner to understand that the struggling and vocalization seen are not due to pain or discomfort. Thus the owner’s perception is that the animal is not experiencing a peaceful death. Clients who choose to be present should be warned that this phase may occur. The use of an ultrashort-acting barbiturate first will minimize the excitement phase.

THE END AS A BEGINNING . . . AFTER THE END

Many veterinary professionals are good at the technical aspects of euthanasia, but fall short in supplying what the client needs after euthanasia has been performed. The animal’s death is often only the beginning of a long and difficult odyssey that the client is about to face. Some clients will feel a great sense of relief immediately after the pet’s death, but most will soon feel empty, numb, or alone. They may question whether they did the right thing. Veterinary professionals can help them by again stressing that the pet’s death was painless, assuring them that they did the right thing, and focusing on the positive things that the pet brought to their life. At the time of euthanasia, it is important that an environment be fostered that says, “It’s all right to cry, it’s all right to be emotional, it’s all right to begin to grieve.” Few of us have the gift of the ability to say the right thing at the right time, so sometimes consolation can best be offered in a touch or an embrace. A touch on the arm or a simple embrace will often express best what the client needs to hear, “We care, and you are not alone.”

Many clients, whether present for the euthanasia or not, need assurance that the animal is dead. Clients will feel more assured by the veterinarian who takes the time to listen to the animal’s thorax with a stethoscope and shine a penlight into the animal’s eyes before pronouncing the patient dead. For those who choose not to be present, allowing them to view the animal’s body can alleviate some of this fear. Before bringing the body to the client, it should be made as presentable as possible. It must always be treated with dignity and respect. Clean any blood from the fur, remove any catheters or bandages, place the tongue in the mouth, and close the eyes. Placing a drop of cyanoacrylate glue (Krazy Glue, Super Glue) in each eye will keep the eyelids closed. If time permits, bathe and brush the animal before laying it on a clean paper, blanket, or towel in a sturdy box. This will help to make the viewing as pleasant an experience as possible. This last, and often lasting, impression that the client takes away from the practice may go a long way toward determining whether he or she returns with another pet. If the animal’s body is sealed in a box (commercially made boxes for home burial are available), let the client know how the body is wrapped and whether any signs of trauma or surgery are present. Even clients who assure the veterinarian that they will not open the box before burial or cremation often change their mind after leaving the office.

Having the client bring someone who will be able to drive him or her home will help ease the feeling of being alone and will also ensure a safe trip. It is nice to call clients after they have arrived home to check on them. Attempts should be made to call all clients who have lost a pet to answer any questions and to show concern. The veterinarian or a staff member may call. The show of concern is always appreciated, helps clients who are having difficulty dealing with grief, and assures clients that a relationship with the practice fostered in life has not been ended by the death of their pet. Most clients will eventually choose to get another pet. A sympathy card or handwritten note is usually appreciated. Many beautiful sympathy cards designed for veterinary use are available (Figure 38-5).

FIGURE 38-5 Follow-up communication is important for the client and the veterinary team. A condolence card lets the client know that you care, and this gesture often brings the client back to your practice when they eventually invest in a new relationship with another pet. In addition, sending a card allows the practice team to empathize, express their own grief, and experience some degree of closure.

One of the biggest concerns of clients who have just lost a pet is disposition of the body. When possible, all arrangements should be made in advance. The veterinary staff should be prepared with information to assist the client in making these arrangements. Know the laws concerning burial in the practice area. Make available names and telephone numbers of places that offer cremation and pet cemetery burial. If the client chooses to have the veterinarian handle the remains, it is best not to lie to the client concerning the disposal of the animal’s body.

Memorializing the pet is a step that many clients find comforting. It can be an important part of grieving for many clients. Offering the client a lock of hair, a clay paw print, and returning collars or leashes may facilitate these wishes (Box 38-6). Having a memorial service, planting a special plant in memory of the pet, framing a photograph, keeping a lock of hair, writing a poem or special letter, offering a memorial scholarship at a veterinary school, or making a donation to organizations, such as the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine or a veterinary school foundation, are actions that clients may use to memorialize their pet (Figure 38-6).

THE STRESS OF EUTHANASIA

Euthanasia is stressful not only to the client, but also to the veterinarian and veterinary staff. Frequent performance of euthanasia is a primary cause of burnout within animal control facilities, shelters, and small animal practice (Box 38-7). It is at times even more stressful to the technical staff than it is to the veterinarian because staff members usually have little control over the situation. Euthanasias that go smoothly and difficult euthanasias will create stress. Difficult or inherently stressful euthanasias include euthanasia in which technical problems arise, instances in which the animal reacts badly to the injections in the presence of the client, and the euthanasia of one’s own pet, healthy animals, young animals, and animals for whom one has put a great deal of time and medical effort into fighting their disease. Euthanasia with the client present usually creates more stress on the veterinary staff than when the procedure is performed in the absence of the owner.

Each individual will have to decide in what type of euthanasia he or she is able to participate and one’s personal tolerance for euthanasia. A technician may not be able to work effectively in a practice in which the veterinarian’s views on euthanasia are vastly different from his or her own. Stress can become intense if these differences are not discussed and reconciled. Veterinarians differ greatly in their views on euthanasia. A survey of British veterinarians revealed that 74% would perform euthanasia on a healthy animal if the owner requested it. A similar survey in Japan revealed that 63% would not. There is room within the veterinary profession for this divergence of views; indeed, the diversity of opinions is one of the profession’s strengths.

One of the most important mechanisms of coping with the stress brought on by euthanasia is discussion with colleagues. Having sessions for the hospital staff in which people can openly express their feelings is a good outlet for emotions that if unexpressed can cause further stress and lead to burnout. This type of communication allows members of the veterinary team to understand their colleagues’ feelings and tolerances for different situations. Members of the team may need to temporarily pass responsibility for euthanasia to their colleagues when they have reached the limit of their tolerance. Other mechanisms of managing stress include taking time off, making time for self, adopting recreational habits, helping clients deal with their grief, and finding strength in relationships formed with colleagues who experience the same stresses.

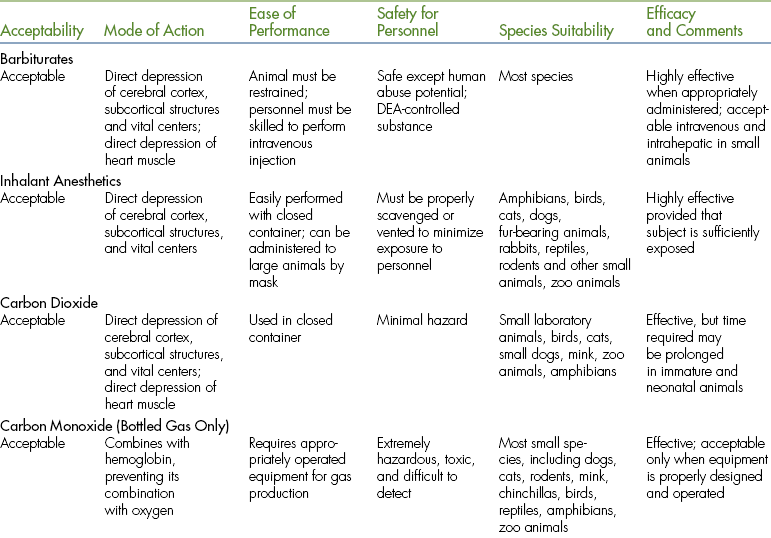

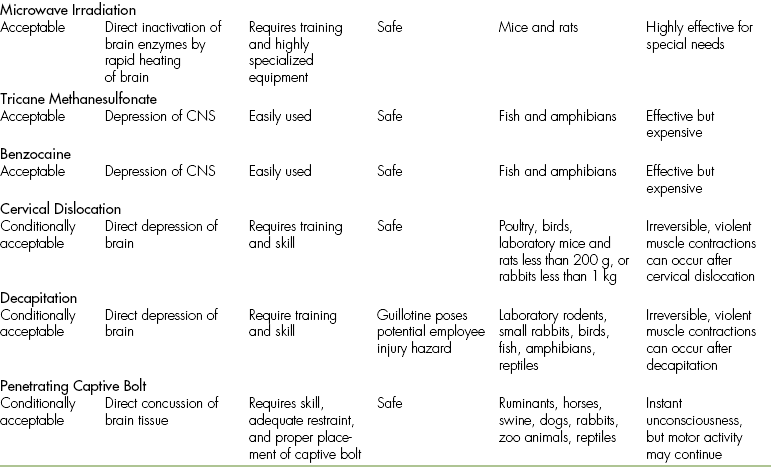

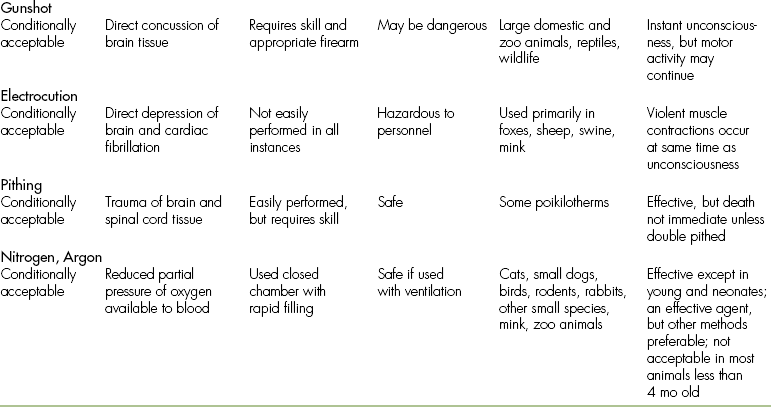

EUTHANASIA IN THE SHELTER AND RESEARCH FACILITY

Technicians in veterinary practice participate in an average of three to six euthanasias per week; however, shelter technicians and potentially research technicians experience much more death than this. Millions of animals must be euthanized each year because there are no homes for them, overpopulation, or because of the needs of certain research protocols. These deaths can be difficult to rationalize, making euthanasia a stressful event for these technicians. The fact that there are different euthanasia methods employed depending on the species or facility is a complicating stressor (Table 38-1). This factor brings up a wide range of both psychosocial and safety issues that need to be addressed.

TABLE 38-1

Summary of Agents and Methods of Euthanasia: Characteristics and Modes of Action

DEA, U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency; CNS, central nervous system.

Modified from Andrews EJ et al: J Am Vet Med Assoc 202(2), 1993.

The stress associated with euthanasia is exemplified in that staff turnover is higher in shelters where euthanasia rates are high compared with those with lower euthanasia rates. Practices that have been associated with decreased turnover rates include provision of a designated euthanasia room, exclusion of other live animals from the vicinity during euthanasia, and removal of euthanized animals from a room before entry of another animal to be euthanized. Staff members involved in the types of euthanasia occurring in shelters or research settings often cope by shifting moral responsibility for killing animals away from themselves. Shelter technicians view their acts as a crusade for animals and against the ignorant public, whereas research technicians may view the euthanasia as necessary for the “greater good.” To prevent burnout, they must see themselves as generators of medical knowledge beneficial to humans and animals, combatants of pet overpopulation, or providers of humane death. These technicians must remember their objectives in their work. Their objective, like every other technician’s, is to prevent and release animals from suffering.

The same mechanisms for coping with the stress of euthanasia mentioned previously are important for both shelter and research technicians. Perhaps one of the most important coping strategies is for the team to rotate euthanasia responsibilities. This rotation releases technicians from the moral stress of euthanasia and reschedules them to a more hopeful task, such as education or adoption responsibilities or other important research missions; it is hoped that giving them a break will prevent burnout. Dark humor is also used to relieve stress. Such humor reduces tension by acknowledging death as part of the setting but also minimizing, for the moment, its tragedy and finality. Although this humor may appear callous and be misunderstood by those outside the shelter or research culture, it has been shown to be an effective coping strategy. It is important to recognize this humor for what it is, a coping mechanism. These technicians care a tremendous amount, but find themselves in an environment without much societal support.

EUTHANASIA OF LARGE ANIMALS

Euthanasia of large domestic animals presents specific hazards and problems not encountered in companion small animals. Safety must be a major consideration. The jugular vein should be used for injection whenever possible because this will place the person injecting the euthanasia solution in the safest position. On rare occasions, thrombosis of the jugular veins may have occurred from disease, and the cephalic vein must be used. However, this puts the individual under the animal’s forequarters and in a dangerous position.

Euthanasia-strength pentobarbital can be administered with a large-gauge needle (14 to 16 gauge). The volume of solution is large, and even with a large-gauge needle, the time it takes to inject the solution is relatively long. The animal may go through the same excitement phase as that experienced by small animals, and it may come crashing to the ground on becoming unconscious. Generally, large animal euthanasia should be performed in an area with vehicle access to allow removal of the body. In some instances, the client may wish to bury a large animal. It should be remembered that all the same emotional concerns encountered in small animal euthanasia pertain to large animals when a bond has formed between the owner and the animal.

CONCLUSION

The loss of a pet and the grieving associated with it is a difficult process, both for the pet owner and for veterinary personnel. Despite this difficulty, veterinary professionals deal with the illness, loss, and euthanasia of their patients on a daily basis, yet they are rarely trained in how best to address the grief of their clients. Nevertheless, it is important for veterinarians and veterinary technicians to provide a positive, supportive environment for pet euthanasia and to help clients with their subsequent loss. If euthanasia is performed poorly, it can be a disastrous experience for both the client and the veterinary practice. If performed with practiced care and gentle concern, it can be remembered positively for a long time. The ability to empathize, maintain a balanced perspective, and be compassionate are essential. The veterinary technician can be available; listening; assuring clients that their feelings, emotions, and struggles are normal; and offering referral when clients think that they need more help than their available support group is able to provide. This form of client help strengthens the bond that develops between the client and the veterinary staff and results in positive growth and added fulfillment for both the client and the veterinary professional.

Anderson, M. Coping with sorrow on the loss of your pet. Los Angeles: Peregrine Press; 1994.

Arluke, A. Coping with euthanasia: a case study of shelter culture. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;198:1176.

AVMA: AVMA guidelines on euthanasia, June, 2007. Available at www.avma.org/issues/animal_welfare/euthanasia.pdf.

Brackenridge, S.S., Elkins, A.D. Euthanasia and patient death: stressors in veterinary practice. Vet Pract Staff. 1992;4:1.

Church, J.A. Joy in a wooly coat. Tiburon, Calif: HJ Kramer; 1987.

Cohen S.P., Fudin C.E., eds. Animal illness and human emotions. Prob Vet Med. 1991;3:1.

Cusack, O. Pets and mental health. New York: Haworth Press; 1988.

Fogle, B., Abrahamson, D. Pet loss: a survey of the attitudes and feelings of practicing veterinarians. Anthrozoos. 1990;3:143.

Fogle, B., Abrahamson, D. Pet loss: attitudes and feelings of practicing veterinarians. Anthrozoos. 1990;3:143.

Grier, R.L., Schaffer, C.B. Evaluation of intraperitoneal and intrahepatic administration of a euthanasia agent in animal shelter cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;197:1611.

Harris, J.M. Nonconventional human/companion animal bonds. In: Kay W.J., Nieburg H.A., Kukscher A.H., eds. Pet loss and human bereavement. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1984.

Hart, L.A., Hart, B.L., Mader, B. Humane euthanasia and companion animal death: caring for the animal, the client, and the veterinarian. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;197:1292.

Katcher, A. Interactions between people and their pets: form and function. In: Fogle B., ed. Interrelations between people and pets. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas, 1981.

Kay, W.J. Euthanasia. Trends. 1985;1:52.

Kay W.J., Cohen S.P., Nieburg H.A., eds. Euthanasia of the companion animal: the impact on pet owners, veterinarians, and society. Baltimore: The Charles Press, 1988.

Kogure, N., Yamazaki, K. Attitudes to animal euthanasia in Japan: a brief review of cultural influences. Anthrozoos. 1990;3:151.

Kübler-Ross, E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan; 1969.

Lagoni, L., Butler, C., Hetts, S. The human animal bond and grief. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994.

Lawrence, E.A. Love for animals and the veterinary profession. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994;205:970.

Nieburg, H.A., Fischer, A. Pet loss: a thoughtful guide for adults and children. New York: Harper & Row; 1982.

Peters, T.G. Commander. JAMA. 1988;260:1460.

Quackenbush, J.E., Glickman, L. Helping people adjust to the death of a pet. Health Soc Work. 1984;9:42.

Quackenbush, J.E., Graveline, D. When your pet dies: how to cope with your feelings. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1985.

Ramsey, E.C., Wetzel, R.W. Comparison of five regimens for oral administration of medication to induce sedation in dogs prior to euthanasia. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213:1170.

Randolph, J.W. Learning from your own pet’s euthanasia. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994;205:544.

Rogelberg, S.G., Reeve, C.L., Spitzmüller, C., et al. Impact of euthanasia rates, euthanasia practices, and human resource practices on employee turnover in animal shelters. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;230:713.

Rosenberg, M.A. Clinical aspects of grief associated with loss of a pet: a veterinarian’s view. In: Kay W.J., Neiburg H.A., Kukscher A.H., eds. Pet loss and human bereavement. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1984.

Stewart, M.F. Companion animal death. Woburn, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999.

Tannenbaum, J. Veterinary ethics. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989.

Veevers, J.E., The social meanings of pets: alternative roles for companion animals. Sussman M.B., ed. Pets and the family, Marriage. Family Rev. 1985;8:11.

Voith, V.L. Attachment of people to companion animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1985;15:289.

Walshaw, S.O. Role of the animal health technician in consoling bereaved clients. In: Kay W.J., Nieburg H.A., Kukscher A.H., eds. Pet loss and human bereavement. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1984.

∗Note that all barbiturates are strictly controlled by federal regulations, and accurate accounting of the use of these agents is required. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) of the U.S. Department of Justice is responsible for enforcement of laws governing the user of barbiturates. Sodium pentobarbital is a schedule II controlled substance and can be obtained only by a licensed medical practitioner, such as a physician, dentist, veterinarian, or approved institution. In addition to the DEA paperwork involved for procuring barbiturates such as sodium pentobarbital, careful handling of the drug is necessary after the drug is on the hospital premises. Thorough record keeping is required by law.

TECHNICIAN NOTE

TECHNICIAN NOTE