Chapter 4 Recognizing the Causes of an Opacified Hemithorax

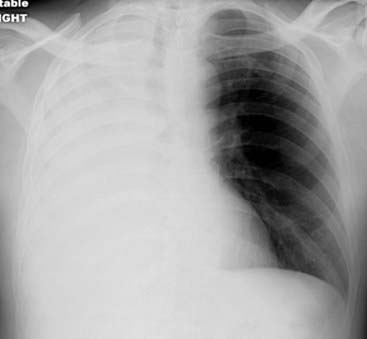

Mr. Smith, age 73, presents to the Emergency Department very short of breath. His frontal chest radiograph is shown in Figure 4-1.

Mr. Smith, age 73, presents to the Emergency Department very short of breath. His frontal chest radiograph is shown in Figure 4-1. As you can see, Mr. Smith’s right hemithorax is almost completely opaque.

As you can see, Mr. Smith’s right hemithorax is almost completely opaque.

Figure 4-1 Mr. Smith comes into the Emergency Department short of breath. This is his frontal chest radiograph.

Would you recommend bronchoscopy for atelectasis, emergent thoracentesis for a large pleural effusion, or a course of antibiotics for his large pneumonia? The answer is on the radiograph (and in this chapter).

Atelectasis of the Entire Lung

Atelectasis of an entire lung usually results from complete obstruction of the right or left main bronchus.

Atelectasis of an entire lung usually results from complete obstruction of the right or left main bronchus.

In an older individual, an obstructing neoplasm, like a bronchogenic carcinoma, might cause atelectasis. In younger individuals, asthma may produce mucous plugs that obstruct the bronchi or a foreign body may have been aspirated. Critically ill patients also develop atelectasis from mucous plugs.

In an older individual, an obstructing neoplasm, like a bronchogenic carcinoma, might cause atelectasis. In younger individuals, asthma may produce mucous plugs that obstruct the bronchi or a foreign body may have been aspirated. Critically ill patients also develop atelectasis from mucous plugs. In obstructive atelectasis, even though there is volume loss within the affected lung, the visceral and parietal pleura almost never separate from each other.

In obstructive atelectasis, even though there is volume loss within the affected lung, the visceral and parietal pleura almost never separate from each other.

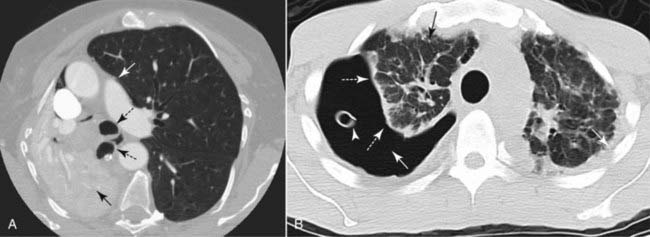

Figure 4-2 Obstructive atelectasis versus a pneumothorax.

Two different causes of lung collapse and the difference in their radiologic appearance. A, There is atelectasis of the entire right lung (solid black arrow) from an obstructing endobronchial lesion. The visceral and parietal pleura remain in contact with each other. Other mobile structures in the mediastinum, such as the trachea and right main bronchus (dotted black arrows), shift toward the atelectasis. The left lung overexpands and crosses the midline (solid white arrow). B, This patient has a large right-sided pneumothorax. Air (solid white arrow) interposes between the visceral (dotted white arrows) and parietal pleurae, causing the lung to undergo passive atelectasis (solid black arrow). A chest tube is seen in the right hemithorax (arrowhead) that had been removed from suction.

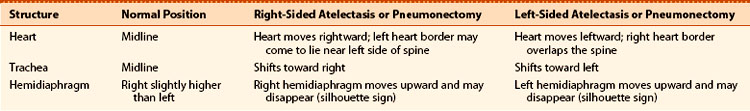

TABLE 4-1 PNEUMOTHORAX VERSUS OBSTRUCTIVE ATELECTASIS

| Feature | Pneumothorax | Obstructive Atelectasis |

|---|---|---|

| Pleural space | Air in the pleural space separates the visceral from the parietal pleura | The visceral and parietal pleura do not separate from each other |

| Density | The pneumothorax itself will appear “black” (air density); the hemithorax may appear more lucent than normal | Atelectasis is the absence of air in the lung; the hemithorax will appear more opaque (“whiter”) than normal |

| Shift | The heart or trachea never shift toward the side of a pneumothorax | The heart and trachea almost always shift toward the side of the atelectasis |

Figure 4-3 Child with wheezing and shortness of breath.

Frontal chest radiograph shows opacification of the entire left hemithorax. The heart has shifted toward the left such that the right heart border no longer projects to the right of the spine. The heart now overlies the spine (solid black arrow). The trachea (solid white arrow) has moved leftward from the midline toward the side of the opacification. These findings are characteristic of atelectasis of the entire lung. The child had asthma. Bronchoscopy was performed and a large mucous plug that was obstructing the left main bronchus was removed.

Massive Pleural Effusion

If fluid, whether blood, an exudate, or a transudate, fills the pleural space so as to opacify almost the entire hemithorax, then the fluid acts like a mass compressing the underlying lung tissue.

If fluid, whether blood, an exudate, or a transudate, fills the pleural space so as to opacify almost the entire hemithorax, then the fluid acts like a mass compressing the underlying lung tissue. When enough pleural fluid accumulates, the large effusion “pushes” mobile structures away, and the heart and trachea shift away from the side of opacification (Fig. 4-4).

When enough pleural fluid accumulates, the large effusion “pushes” mobile structures away, and the heart and trachea shift away from the side of opacification (Fig. 4-4). Massive pleural effusions are frequently the result of malignancy, either in the form of a bronchogenic carcinoma or secondary to metastases to the pleura from a distant organ. Trauma can produce a hemothorax and tuberculosis is notorious for causing large, clinically silent effusions. The effusions from congestive heart failure, while very common, are most often bilateral (but asymmetrical) and they rarely grow large enough to occupy an entire hemithorax.

Massive pleural effusions are frequently the result of malignancy, either in the form of a bronchogenic carcinoma or secondary to metastases to the pleura from a distant organ. Trauma can produce a hemothorax and tuberculosis is notorious for causing large, clinically silent effusions. The effusions from congestive heart failure, while very common, are most often bilateral (but asymmetrical) and they rarely grow large enough to occupy an entire hemithorax.

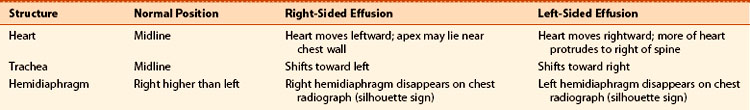

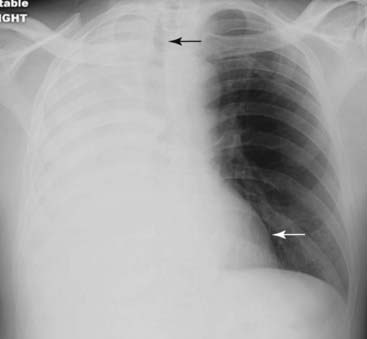

Figure 4-4 Complete opacification of the right hemithorax.

The trachea is deviated to the left (solid black arrow) and the apex of the heart is also displaced to the left, close to the lateral chest wall (solid white arrow). These findings are characteristic of a large pleural effusion that is producing a mass effect. Almost two liters of serosanguinous fluid were removed at thoracentesis. The fluid contained malignant cells from a primary bronchogenic carcinoma.

![]() At times, there may be a perfect balance between the push of a malignant effusion and the pull of underlying obstructive atelectasis from the malignancy itself.

At times, there may be a perfect balance between the push of a malignant effusion and the pull of underlying obstructive atelectasis from the malignancy itself.

In an adult patient with an opacified hemithorax, no air bronchograms and little or no shift of the mobile thoracic structures, it is important to suspect an obstructing bronchogenic carcinoma, perhaps with metastases to the pleura. A CT scan of the chest will reveal the abnormalities (Fig. 4-5).

In an adult patient with an opacified hemithorax, no air bronchograms and little or no shift of the mobile thoracic structures, it is important to suspect an obstructing bronchogenic carcinoma, perhaps with metastases to the pleura. A CT scan of the chest will reveal the abnormalities (Fig. 4-5). Table 4-3 summarizes the movement of the mobile structures in the thorax in patients with a large pleural effusion.

Table 4-3 summarizes the movement of the mobile structures in the thorax in patients with a large pleural effusion.

Figure 4-5 Atelectasis and effusion.

A balance exists between a large pleural effusion (E) and atelectasis of the right lung (solid black arrow) so that there is no significant resultant shift of the mobile midline structures. The heart remains in essentially its normal position (solid white arrow). This combination of findings is highly suggestive of a central bronchogenic malignancy with a malignant effusion.

Pneumonia of an Entire Lung

With pneumonia, inflammatory exudate fills the air spaces causing consolidation and opacification of the lung.

With pneumonia, inflammatory exudate fills the air spaces causing consolidation and opacification of the lung. The hemithorax becomes opaque because the lung no longer contains air, but there is neither a pull toward the side of the pneumonia by volume loss nor a push away from the side of the pneumonia by a large effusion.

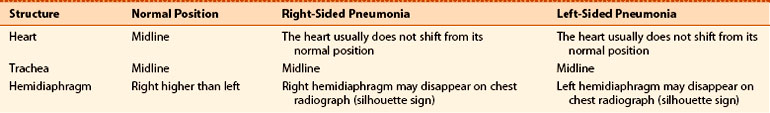

The hemithorax becomes opaque because the lung no longer contains air, but there is neither a pull toward the side of the pneumonia by volume loss nor a push away from the side of the pneumonia by a large effusion. Table 4-4 summarizes the movement of the mobile structures in the thorax in patients with pneumonia of the entire lung.

Table 4-4 summarizes the movement of the mobile structures in the thorax in patients with pneumonia of the entire lung.

Figure 4-6 Pneumonia of the left upper lobe.

There is near-complete opacification of the left hemithorax with no shift of the heart and little shift of the trachea (solid white arrows). Air bronchograms are suggested within the upper area of opacification (circle). These findings suggest a pneumonia rather than atelectasis or pleural effusion. The patient had Streptococcus pneumoniae present in the sputum and improved quickly on antibiotics.

Postpneumonectomy

Pneumonectomy means the removal of an entire lung.

Pneumonectomy means the removal of an entire lung.

For about 24 hours following the surgery, only air occupies the hemithorax from which the lung has been removed (Fig. 4-7).

For about 24 hours following the surgery, only air occupies the hemithorax from which the lung has been removed (Fig. 4-7). Eventually, fibrous tissue forms in the pneumonectomized hemithorax and in most patients the entire hemithorax is completely opaque. The heart and trachea shift toward the side of opacification.

Eventually, fibrous tissue forms in the pneumonectomized hemithorax and in most patients the entire hemithorax is completely opaque. The heart and trachea shift toward the side of opacification.

Figure 4-7 Postpneumonectomy day 1, right lung.

A pneumonectomy is the removal of the entire lung. This postoperative radiograph was obtained less than 24 hours after this patient underwent a pneumonectomy on the right side for a bronchogenic carcinoma. Surgical clips are in the region of the right hilum (solid black arrows), and the right 5th rib has been surgically removed in order to perform the pneumonectomy. Over the next several weeks, the right hemithorax will fill with fluid, and the heart and mediastinal structures will gradually shift toward the side of the pneumonectomy (see Fig. 4-8).

![]() The chest examination looks identical to that of a patient with atelectasis of the entire lung. To tell the difference, look for the missing 5th or 6th rib and look for the surgical clips in the hilum to indicate a pneumonectomy has been performed (Fig. 4-8).

The chest examination looks identical to that of a patient with atelectasis of the entire lung. To tell the difference, look for the missing 5th or 6th rib and look for the surgical clips in the hilum to indicate a pneumonectomy has been performed (Fig. 4-8).

So let’s return to the frontal radiograph of Mr. Smith with the opacified hemithorax, who has been waiting patiently in the Emergency Department while you read this chapter.

So let’s return to the frontal radiograph of Mr. Smith with the opacified hemithorax, who has been waiting patiently in the Emergency Department while you read this chapter.

Figure 4-8 One year after pneumonectomy.

There is complete opacification of the right hemithorax. The right 5th rib (solid black arrow) is surgically absent. The heart (solid white arrow) and trachea (dotted black arrow) are deviated towards the side of opacification. These signs are characteristic of volume loss. The surgery had been performed one year earlier for a bronchogenic carcinoma. The fluid that gradually filled the right hemithorax immediately following the pneumonectomy has probably fibrosed, leading to a permanent shift towards the pneumonectomized side.

Figure 4-9 Mr. Smith’s frontal chest radiograph.

The entire right hemithorax is opacified. The trachea has shifted toward the right (solid black arrow), and the heart is displaced toward the right as well (solid white arrow). Both of these mobile structures have moved toward the side of opacification. These signs are characteristic of atelectasis of the entire right lung and in a patient like Mr. Smith, who is 73, a bronchogenic carcinoma is the most likely diagnosis. An obstructing carcinoma was found at bronchoscopy in the right main bronchus.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing the Causes of an Opacified Hemithorax on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing the Causes of an Opacified Hemithorax

The differential possibilities for an opacified hemithorax should include atelectasis of the entire lung, a very large pleural effusion, pneumonia of the entire lung, or post-pneumonectomy.

The trachea, heart, and hemidiaphragms are mobile structures that have the capability of moving (shifting) if there is either something pushing on them or something pulling them.

With atelectasis, there is a shift toward the side of the opacified hemithorax because of volume loss in the affected lung.

With a large pleural effusion, there is a shift away from the side of opacification because the large pleural effusion can act as if it were a mass.

With pneumonia of an entire lung, there is usually no shift, but air bronchograms may be present.

Occasionally, the shift of a malignant effusion may be balanced by the opposite shift of atelectasis caused by an underlying, obstructing bronchogenic carcinoma so that the hemithorax will be completely opaque but there will be no shift.

In the post-pneumonectomy patient, there is eventually volume loss on the side from which the lung has been removed, and the clues to such surgery may include surgical absence of the 5th or 6th rib on the affected side or metallic surgical clips in the hilum.