Chapter 23 Recognizing Joint Disease

An Approach to Arthritis

Imaging studies play a key role in the diagnosis and management of arthritis and are the method by which many arthritides are first diagnosed. Other arthritides are initially diagnosed on clinical and laboratory grounds and imaging is used to document the severity, extent, and course of the disease (Table 23-1).

Imaging studies play a key role in the diagnosis and management of arthritis and are the method by which many arthritides are first diagnosed. Other arthritides are initially diagnosed on clinical and laboratory grounds and imaging is used to document the severity, extent, and course of the disease (Table 23-1). Conventional radiographs demonstrate osseous abnormalities but provide only indirect and usually delayed evidence of abnormalities involving the soft tissues, such as the synovial lining of the joint, the articular cartilage, muscles, ligaments, and tendons surrounding the joint. MRI is used to demonstrate those soft tissue abnormalities.

Conventional radiographs demonstrate osseous abnormalities but provide only indirect and usually delayed evidence of abnormalities involving the soft tissues, such as the synovial lining of the joint, the articular cartilage, muscles, ligaments, and tendons surrounding the joint. MRI is used to demonstrate those soft tissue abnormalities.TABLE 23-1 ARTHRITIS: WHO MAKES THE DIAGNOSIS?

| Usually Diagnosed Clinically | Frequently Diagnosed Radiologically |

|---|---|

| Septic (pyogenic) arthritis | Osteoarthritis |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Early rheumatoid arthritis |

| Gout | Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | |

| Hemophilia | Septic (TB) |

| Charcot (neuropathic) joint—late |

Anatomy of A Joint

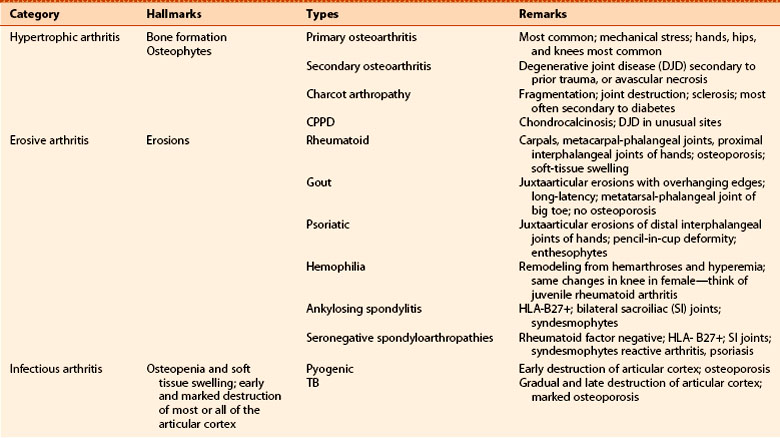

Figure 23-1 contains a diagram of a typical synovial joint and compares the structures visualized on conventional radiographs and MRI.

Figure 23-1 contains a diagram of a typical synovial joint and compares the structures visualized on conventional radiographs and MRI. The articular cortex is the thin, white line as seen on conventional radiographs that lies within the joint capsule and is usually capped by hyaline cartilage, called the articular cartilage. The bone immediately beneath the articular cortex is called subchondral bone.

The articular cortex is the thin, white line as seen on conventional radiographs that lies within the joint capsule and is usually capped by hyaline cartilage, called the articular cartilage. The bone immediately beneath the articular cortex is called subchondral bone. Lining the joint capsule is the synovial membrane containing synovial fluid. The synovial membrane is frequently the earliest structure involved by an arthritis.

Lining the joint capsule is the synovial membrane containing synovial fluid. The synovial membrane is frequently the earliest structure involved by an arthritis. Conventional radiographs will demonstrate abnormalities of the articular cortex and the subchondral bone and will provide late, indirect evidence of the integrity of the articular cartilage.

Conventional radiographs will demonstrate abnormalities of the articular cortex and the subchondral bone and will provide late, indirect evidence of the integrity of the articular cartilage. On conventional radiographs, the synovial membrane, synovial fluid, and the articular cartilage are usually not directly visible. All, however, are visible using MRI.

On conventional radiographs, the synovial membrane, synovial fluid, and the articular cartilage are usually not directly visible. All, however, are visible using MRI. While MRI is more sensitive in directly visualizing the soft tissues in and around a joint, conventional radiographs remain the study of first choice in evaluating for the presence of an arthritis.

While MRI is more sensitive in directly visualizing the soft tissues in and around a joint, conventional radiographs remain the study of first choice in evaluating for the presence of an arthritis.

Figure 23-1 Diagram, radiograph, and MRI image of a true joint.

A, A representation of a synovial joint shows the articular cortex, which corresponds to the thin, white line within the joint capsule that is usually capped by articular cartilage. The bone immediately beneath the articular cortex is called subchondral bone. Within the joint capsule is the synovial membrane and synovial fluid. B, On conventional radiographs, the articular cortex (solid white arrow) and subchondral bone (solid black arrows) are visible but the cartilage and synovial fluid are not (dotted white arrow). C, A T1-weighted coronal MRI of the knee shows the medial (MM) and lateral (LM) menisci, anterior (ACL) and posterior (PCL) cruciate ligaments, articular cartilage (dotted black arrow), joint capsule (dotted white arrow), synovial fluid (solid white arrow), and marrow in the subchondral bone (SC). The cortex of the bone (solid black arrow) produces little signal and is dark.

Classification of Arthritis

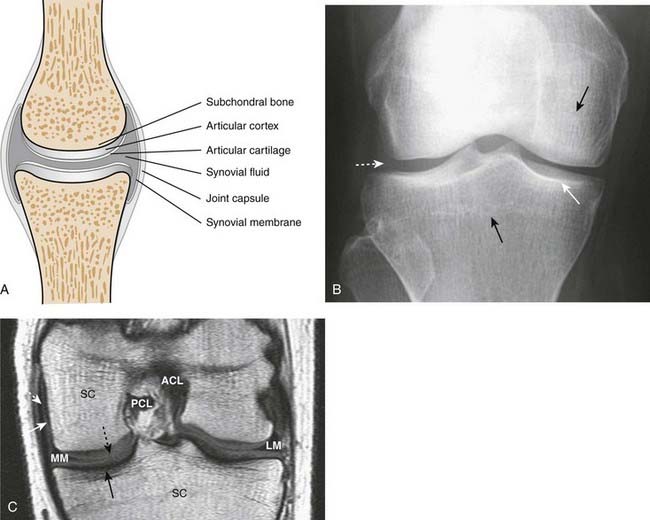

First, let’s define what an arthritis is and then we’ll outline a classification of arthritides. An arthritis is a disease that affects a joint and usually the bones on either side of the joint, almost always accompanied by joint space narrowing (Fig. 23-2).

First, let’s define what an arthritis is and then we’ll outline a classification of arthritides. An arthritis is a disease that affects a joint and usually the bones on either side of the joint, almost always accompanied by joint space narrowing (Fig. 23-2). We will divide arthritides into three main categories: (Table 23-2)

We will divide arthritides into three main categories: (Table 23-2)

Within each of these three main categories, we’ll look at a few of the more common types of arthritis that also have characteristic imaging findings.

Within each of these three main categories, we’ll look at a few of the more common types of arthritis that also have characteristic imaging findings.

An arthritis is a disease that affects a joint and usually the bones on either side of the joint, almost always accompanied by joint space narrowing. A, This disease meets those specifications. There is narrowing of the hip joint, and both the femoral head and the acetabulum are abnormal (solid white arrow). This is osteoarthritis of the hip. B, There is an abnormality of the femoral head (sclerosis) but the joint space is normal as is the acetabulum (solid black arrow). This is avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

Figure 23-3 The imaging hallmarks of the three major categories of arthritis.

A, Hypertrophic arthritis features subchondral sclerosis (solid black arrow) and marginal osteophyte production (solid white arrow). B, Erosive (inflammatory) arthritis features characteristic marginal lytic erosions (solid white and black arrows). C, Infectious arthritis features destruction of the articular cortex (dotted white arrow).

Hypertrophic Arthritis

Hypertrophic arthritis is characterized by bone formation, either within the confines of preexisting bone (subchondral sclerosis) or by bony protrusions extending from the normal bone (osteophytes).

Hypertrophic arthritis is characterized by bone formation, either within the confines of preexisting bone (subchondral sclerosis) or by bony protrusions extending from the normal bone (osteophytes). Hypertrophic arthritides include:

Hypertrophic arthritides include:

Primary Osteoarthritis (Also Known as Primary Degenerative Arthritis, Degenerative Joint Disease)

This is the most common form of arthritis, estimated to affect over 20 million Americans. It results from intrinsic degeneration of the articular cartilage, mostly from the mechanical stress of excessive wear and tear in weight-bearing joints.

This is the most common form of arthritis, estimated to affect over 20 million Americans. It results from intrinsic degeneration of the articular cartilage, mostly from the mechanical stress of excessive wear and tear in weight-bearing joints. Marginal osteophyte formation. A hallmark of hypertrophic arthritis, osseous transformation of cartilaginous excrescences and metaplasia of synovial lining cells lead to the production of these bony protrusions at or near the joint (Fig. 23-4).

Marginal osteophyte formation. A hallmark of hypertrophic arthritis, osseous transformation of cartilaginous excrescences and metaplasia of synovial lining cells lead to the production of these bony protrusions at or near the joint (Fig. 23-4). Subchondral sclerosis. This is a reaction of the bone to the mechanical stress to which it is subjected when its protective cartilage has been destroyed.

Subchondral sclerosis. This is a reaction of the bone to the mechanical stress to which it is subjected when its protective cartilage has been destroyed. Subchondral cysts. As a result of chronic impaction, necrosis of bone and imposition of synovial fluid into the subchondral bone, cysts of varying sizes form in the subchondral bone.

Subchondral cysts. As a result of chronic impaction, necrosis of bone and imposition of synovial fluid into the subchondral bone, cysts of varying sizes form in the subchondral bone. What joints are involved?

What joints are involved?

The hallmarks of osteoarthritis are demonstrated in this patient’s right hip. There is marginal osteophyte formation (solid white arrow), a process by which osseous transformation of cartilaginous excrescences and metaplasia of synovial lining cells leads to the production of bony protrusions at or near the joint. There is also subchondral sclerosis (solid black arrows), representing reaction of the bone to the mechanical stress to which it is subjected when its protective cartilage has been destroyed. Subchondral cyst formation is also present(dotted black arrow).

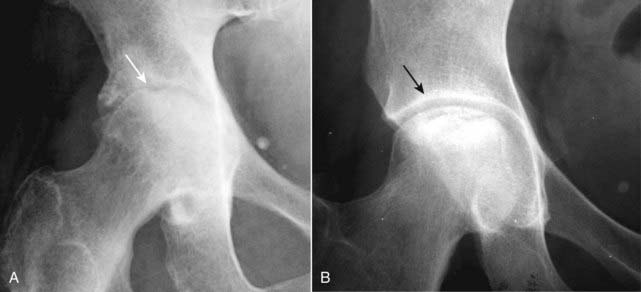

Figure 23-5 Osteoarthritis of hip (A) and knee (B).

In osteoarthritis, destruction of the cartilaginous buffer between the apposing bones of a joint leads to narrowing of the joint space most often on the weight-bearing side of the joint. In the hip (A), the superior and lateral surface is most affected (solid white arrow) while in the knee (B), the medial compartment is more affected (solid black arrow).

Figure 23-6 Osteoarthritis of the hands (A and B).

In the hands, osteoarthritis affects primarily the distal and then proximal interphalangeal joints. There are osteophytes at the distal and proximal phalangeal joints (solid white arrows) and the joint spaces are narrowed. There is also subchondral sclerosis present at the carpal-metacarpal joint of the thumb (solid black arrow). Osteoarthritis of the hands occurs most often in older women.

Secondary Osteoarthritis (Secondary Degenerative Arthritis)

Secondary osteoarthritis is a form of degenerative arthritis of synovial joints that occurs because of an underlying, predisposing condition, most frequently trauma, that damages or leads to damage of the articular cartilage.

Secondary osteoarthritis is a form of degenerative arthritis of synovial joints that occurs because of an underlying, predisposing condition, most frequently trauma, that damages or leads to damage of the articular cartilage. The radiographic findings of secondary osteoarthritis are the same as those for the primary form with several special clues to help suggest secondary osteoarthritis:

The radiographic findings of secondary osteoarthritis are the same as those for the primary form with several special clues to help suggest secondary osteoarthritis:

Figure 23-7 Secondary osteoarthritis, right hip.

Notice the marked discrepancy between the two hips with severe and advanced osteoarthritis of the right hip (solid black arrow) and a normal left hip (solid white arrow). The radiographic findings of secondary osteoarthritis are the same as those for the primary form except it occurs at an atypical age for primary osteoarthritis, it has an atypical appearance for primary osteoarthritis, and it may appear in an unusual location for primary osteoarthritis. This patient had a slipped capital femoral epiphysis on the right, and it was never attended to medically.

![]() Eventually any arthritis that affects the articular cartilage, no matter what the etiology, can lead to changes of secondary osteoarthritis.

Eventually any arthritis that affects the articular cartilage, no matter what the etiology, can lead to changes of secondary osteoarthritis.

Erosive Osteoarthritis

Erosive osteoarthritis is a type of primary osteoarthritis characterized by more severe inflammation and by the development of erosive changes. It occurs most often in perimenopausal females.

Erosive osteoarthritis is a type of primary osteoarthritis characterized by more severe inflammation and by the development of erosive changes. It occurs most often in perimenopausal females. Erosive osteoarthritis may feature bilaterally symmetrical changes such as the osteophytes of primary osteoarthritis but with marked inflammation (swelling and tenderness) and erosions at the affected joints.

Erosive osteoarthritis may feature bilaterally symmetrical changes such as the osteophytes of primary osteoarthritis but with marked inflammation (swelling and tenderness) and erosions at the affected joints.

Figure 23-8 Erosive osteoarthritis.

A type of primary osteoarthritis characterized by more severe inflammation and by the development of erosive changes, erosive osteoarthritis may feature bilaterally symmetrical changes like the osteophytes of DJD but with marked inflammation (swelling and tenderness). The erosions are typically centrally located within the joint (solid black arrows) and, combined with the small osteophytes associated with the disease (solid white arrows), produce what has been called the gull-wing deformity.

Charcot Arthropathy (Neuropathic Joint)

Charcot arthropathy develops from a disturbance in sensation that leads to multiple microfractures as well as an autonomic imbalance that leads to hyperemia, bone resorption, and fragmentation of bone.

Charcot arthropathy develops from a disturbance in sensation that leads to multiple microfractures as well as an autonomic imbalance that leads to hyperemia, bone resorption, and fragmentation of bone. Even though the joint lacks sensory feedback, almost three out of four patients with a Charcot joint complain of some degree of pain, although it is usually far less than would be expected for the degree of joint destruction present.

Even though the joint lacks sensory feedback, almost three out of four patients with a Charcot joint complain of some degree of pain, although it is usually far less than would be expected for the degree of joint destruction present. The most common cause of a Charcot joint today is diabetes, and most Charcot joints are found in the lower extremities, particularly in the feet and ankles.

The most common cause of a Charcot joint today is diabetes, and most Charcot joints are found in the lower extremities, particularly in the feet and ankles. The hallmark findings of a Charcot joint:

The hallmark findings of a Charcot joint:

A Charcot joint shares findings with osteomyelitis, and the two may mimic each other in that they both produce bone destruction and periosteal reaction (from fracture healing). A radioactive Indium-tagged white-cell bone scan can help to differentiate infection from Charcot joint.

A Charcot joint shares findings with osteomyelitis, and the two may mimic each other in that they both produce bone destruction and periosteal reaction (from fracture healing). A radioactive Indium-tagged white-cell bone scan can help to differentiate infection from Charcot joint.

Figure 23-9 Charcot arthropathy of knees.

As a hypertrophic arthritis, a Charcot joint will demonstrate extensive subchondral sclerosis. The hallmark findings of a Charcot joint, however, are fragmentation of the bones surrounding the joint, which produces numerous small, bony densities within the joint capsule (solid white arrows) as well as joint space destruction (solid black arrows). The most common cause of a Charcot joint of the knee is diabetes.

Figure 23-10 Charcot arthropathy of foot.

This patient had previously undergone an amputation of the phalanges of the second toe (solid white arrow) for diabetic gangrene but the destruction and marked fragmentation of the great toe are manifestations of Charcot neuropathy (solid black arrows). Charcot neuropathy can produce some of the most dramatic examples of total joint destruction of any arthritis.

Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease (Pyrophosphate Arthropathy)

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease is an arthropathy resulting from the deposition of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystals in and around joints, mostly in hyaline cartilage and fibrocartilage. This is especially common in the triangular fibrocartilage of the wrist and the menisci of the knee.

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease is an arthropathy resulting from the deposition of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystals in and around joints, mostly in hyaline cartilage and fibrocartilage. This is especially common in the triangular fibrocartilage of the wrist and the menisci of the knee. The terminology associated with describing this disease can be confusing.

The terminology associated with describing this disease can be confusing.

Figure 23-11 Chondrocalcinosis.

Chondrocalcinosis refers only to calcification of the articular cartilage (solid white arrows) or fibrocartilage and is seen in about 50% of adults over the age of 85, most of whom are asymptomatic. If this patient had acute pain, redness, swelling, and limitation of motion, the combination would be called pseudogout.

![]() Pyrophosphate arthropathy may be indistinguishable from primary osteoarthritis but differs from it in several important respects:

Pyrophosphate arthropathy may be indistinguishable from primary osteoarthritis but differs from it in several important respects:

Figure 23-12 Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD).

CPPD arthropathy produces changes similar to osteoarthritis but differs from it in that CPPD affects joints not usually affected by primary osteoarthritis. A, Hook-shaped bony excrescences along the 2nd and 3rd metacarpal heads are a common finding in CPPD (solid white arrows). The radiocarpal joint is narrowed (solid black arrow). B, In the wrist, characteristic findings include calcification of the triangular fibrocartilage (solid white arrow), separation of the scaphoid (S) and the lunate (L) (scapholunate dissociation) and collapse of the capitate (C) toward the radius (solid black arrow) called scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC).

Erosive Arthritis

Erosive arthritis comprises a large number of arthritides, all of which are associated with some degree of inflammation and synovial proliferation (pannus formation), which participates in the production of lytic lesions in or near the joint called erosions, especially in the small joints of the hands and feet.

Erosive arthritis comprises a large number of arthritides, all of which are associated with some degree of inflammation and synovial proliferation (pannus formation), which participates in the production of lytic lesions in or near the joint called erosions, especially in the small joints of the hands and feet. Pannus acts like a mass of growing and enlarging synovial tissue, which leads to marginal erosions of the articular cartilage and underlying bone.

Pannus acts like a mass of growing and enlarging synovial tissue, which leads to marginal erosions of the articular cartilage and underlying bone. Box 23-2 lists some of the many causes of erosive arthritis. We shall talk about only four of the more common.

Box 23-2 lists some of the many causes of erosive arthritis. We shall talk about only four of the more common.Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is more common in females, frequently involving the proximal joints of the hands and wrists. It is usually bilateral and symmetrical.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is more common in females, frequently involving the proximal joints of the hands and wrists. It is usually bilateral and symmetrical. Conventional radiographs remain the study of first choice in imaging RA.

Conventional radiographs remain the study of first choice in imaging RA.

![]() The earliest radiographic changes are soft tissue swelling of the affected joints and osteoporosis, which tends to be most severe on both sides of the joint space (periarticular osteoporosis or periarticular demineralization).

The earliest radiographic changes are soft tissue swelling of the affected joints and osteoporosis, which tends to be most severe on both sides of the joint space (periarticular osteoporosis or periarticular demineralization).

In the hand, the erosions tend to involve the proximal joints: the carpal-metacarpal, metacarpal-phalangeal, and proximal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 23-13).

In the hand, the erosions tend to involve the proximal joints: the carpal-metacarpal, metacarpal-phalangeal, and proximal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 23-13).

In the wrist, erosions of the carpals, ulnar styloid, and narrowing of the radio-carpal joint space are frequently seen.

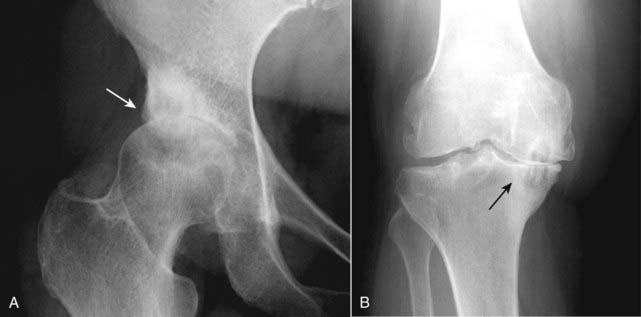

In the wrist, erosions of the carpals, ulnar styloid, and narrowing of the radio-carpal joint space are frequently seen. Elsewhere in the body, the larger joints usually show no erosions, but there may be marked uniform narrowing of the joint space with little or no subchondral sclerosis (Fig. 23-14).

Elsewhere in the body, the larger joints usually show no erosions, but there may be marked uniform narrowing of the joint space with little or no subchondral sclerosis (Fig. 23-14). In the spine, RA tends to involve the cervical spine by producing ligamentous laxity, which can lead to forward subluxation of C1 on C2 (atlantoaxial subluxation). Atlantoaxial subluxation can produce cord compression if severe (Fig. 23-15).

In the spine, RA tends to involve the cervical spine by producing ligamentous laxity, which can lead to forward subluxation of C1 on C2 (atlantoaxial subluxation). Atlantoaxial subluxation can produce cord compression if severe (Fig. 23-15).

Figure 23-13 Rheumatoid arthritis, hand (A) and wrist (B).

A, In the hand, the erosions of RA tend to involve the proximal joints: the carpal-metacarpal joints, metacarpal-phalangeal (solid white arrows), and proximal interphalangeal joints. Late findings in the hands include deformities such as ulnar deviation of the fingers at the MCP joints, subluxation of the MCP joints, and ligamentous laxity leading to deformities of the fingers, which are also present in this hand. B, In the wrist, erosions of the carpals (dotted white arrow), ulnar styloid (solid white arrow), and narrowing of the radiocarpal joint space (solid black arrow) are commonly seen.

Figure 23-14 Rheumatoid arthritis of the hip.

The larger joints (hips and knees) usually show no erosions, but there may be marked uniform narrowing of the joint space with little or no subchondral sclerosis (solid black arrow). If this were primary osteoarthritis, you would expect far more subchondral sclerosis and osteophyte production for this degree of joint space narrowing.

Figure 23-15 Rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine.

RA tends to involve the cervical spine by producing ligamentous laxity, which can lead to forward subluxation of C1 on C2 (atlantoaxial subluxation). The distance between the anterior border of the dens (D) and the posterior border of the anterior tubercle of C1 (T) is called the predentate space and is normally no more than 3 mm. This patient’s predentate space measured 8 mm (solid black arrow). RA may also cause fusion of the facet joints (solid white arrow).

Gout

Gout represents the inflammatory changes incited by the deposition of calcium urate crystals in the joint. There is characteristically an extremely long latent period (5 to 7 years) between the onset of symptoms and the visualization of bone changes, so gout is usually a clinical and not a radiologic diagnosis (see Table 23-1).

Gout represents the inflammatory changes incited by the deposition of calcium urate crystals in the joint. There is characteristically an extremely long latent period (5 to 7 years) between the onset of symptoms and the visualization of bone changes, so gout is usually a clinical and not a radiologic diagnosis (see Table 23-1). It is more common in males and most commonly affects the metatarsal-phalangeal joint of the great toe at the time of symptom onset.

It is more common in males and most commonly affects the metatarsal-phalangeal joint of the great toe at the time of symptom onset.

As an erosive arthritis, the hallmark of gout is the sharply marginated, juxtaarticular erosion which tends to have a sclerotic border. The overhanging edges of gouty erosions have been called rat bites.

As an erosive arthritis, the hallmark of gout is the sharply marginated, juxtaarticular erosion which tends to have a sclerotic border. The overhanging edges of gouty erosions have been called rat bites. Joint space narrowing may be a late finding in the disease, and there is characteristically little or no periarticular osteoporosis (Fig. 23-16).

Joint space narrowing may be a late finding in the disease, and there is characteristically little or no periarticular osteoporosis (Fig. 23-16). Tophi, collections of urate crystals in the soft tissues, are a late finding in gout and rarely calcify.

Tophi, collections of urate crystals in the soft tissues, are a late finding in gout and rarely calcify.

Gout most commonly affects the metatarsal-phalangeal joint of the great toe, as in this patient. As an erosive arthritis, the hallmark of gout is the sharply marginated, juxtaarticular erosion which may have a sclerotic border (solid white arrows). The overhanging edges of gouty erosions have been called rat bites. The metatarsal-phalangeal joint space is not particularly narrowed, and there is no periarticular osteoporosis.

Figure 23-17 Olecranon bursitis in gout.

Olecranon bursitis is a common manifestation of gout (large soft tissue mass around elbow shown by solid white arrows) and its presence alone should alert you to the possibility of underlying gout. This patient also displays erosions adjacent to the elbow joint (solid black arrow).

Psoriatic Arthritis

Most patients with psoriatic arthritis also have skin and nail changes of psoriasis for many years, although, for some, the joint manifestations may be the initial presentation of the disease. About 25% of patients with long-standing psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis. It is usually polyarticular.

Most patients with psoriatic arthritis also have skin and nail changes of psoriasis for many years, although, for some, the joint manifestations may be the initial presentation of the disease. About 25% of patients with long-standing psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis. It is usually polyarticular. Psoriatic arthritis typically involves the small joints of the hands, especially the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints.

Psoriatic arthritis typically involves the small joints of the hands, especially the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints.

Resorption of the terminal phalanges or the DIP joints with telescoping of one phalanx into another (pencil-in-cup deformity) (Fig. 23-18).

Resorption of the terminal phalanges or the DIP joints with telescoping of one phalanx into another (pencil-in-cup deformity) (Fig. 23-18). In the sacroiliac joints, psoriasis can produce bilateral, but asymmetric, sacroiliitis. The SI joints do not usually completely fuse as they do in ankylosing spondylitis.

In the sacroiliac joints, psoriasis can produce bilateral, but asymmetric, sacroiliitis. The SI joints do not usually completely fuse as they do in ankylosing spondylitis.

Figure 23-18 Psoriatic arthritis, hand (A) and foot (B).

A, Psoriatic arthritis typically involves the small joints of the hands, especially the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (solid white arrows) leading to telescoping of one phalanx into another (pencil-in-cup deformity). B, In the foot of another patient with psoriasis, there is ankylosis of the 2nd toe (solid black arrow) and more pencil-in-cup deformities (dotted white arrows).

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic and progressive arthritis characterized by inflammation and eventual fusion of the sacroiliac joints along with the spinal facet joints and involvement of the paravertebral soft tissues.

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic and progressive arthritis characterized by inflammation and eventual fusion of the sacroiliac joints along with the spinal facet joints and involvement of the paravertebral soft tissues. More common in young males, the disease characteristically ascends the spine starting in the SI joints and moving to the lumbar, thoracic, and finally cervical spine.

More common in young males, the disease characteristically ascends the spine starting in the SI joints and moving to the lumbar, thoracic, and finally cervical spine. Almost all patients with ankylosing spondylitis test positive for the human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) as opposed to only about 5 to 10% of the general population.

Almost all patients with ankylosing spondylitis test positive for the human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) as opposed to only about 5 to 10% of the general population. Conventional radiographs of the affected areas are the usual study performed for diagnosis and follow-up of patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Conventional radiographs of the affected areas are the usual study performed for diagnosis and follow-up of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ankylosing spondylitis is an enthesopathy, a process that produces inflammation, with subsequent calcification and ossification at and around the entheses, which are the insertion sites of tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules.

Ankylosing spondylitis is an enthesopathy, a process that produces inflammation, with subsequent calcification and ossification at and around the entheses, which are the insertion sites of tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules.

It is usually bilaterally symmetrical and eventually leads to bony fusion or ankylosis of these joints until they appear either as a thin white line (instead of a joint space) or they disappear altogether (Fig. 23-19).

It is usually bilaterally symmetrical and eventually leads to bony fusion or ankylosis of these joints until they appear either as a thin white line (instead of a joint space) or they disappear altogether (Fig. 23-19). In the spine, ossification of the outer fibers of the annulus fibrosis produces thin, bony bridges from the corners of one vertebra to another called syndesmophytes. Progressive syndesmophytes production connecting adjacent vertebral bodies produces a bamboo-spine appearance (Fig. 23-20).

In the spine, ossification of the outer fibers of the annulus fibrosis produces thin, bony bridges from the corners of one vertebra to another called syndesmophytes. Progressive syndesmophytes production connecting adjacent vertebral bodies produces a bamboo-spine appearance (Fig. 23-20).

Figure 23-19 Ankylosing spondylitis.

Ankylosing spondylitis is an enthesopathy, a process that produces inflammation with subsequent calcification and ossification at and around the entheses, which are the insertion sites of tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules (solid white arrow points to bony overgrowth at the ischial tuberosity). Bilaterally symmetrical sacroiliitis is the hallmark of ankylosing spondylitis. This eventually leads to bony fusion or ankylosis of the SI joints until they disappear as joints altogether (solid black arrows). The symphysis pubis is also ankylosed (dotted black arrow).

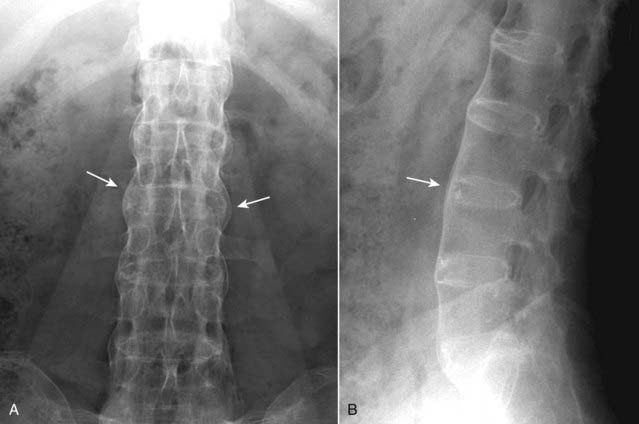

Figure 23-20 Ankylosing spondylitis, frontal (A) and lateral (B) spine.

In the spine, there is ossification of the outer fibers of the annulus fibrosus producing thin, bony bridges joining the corners of adjacent vertebrae called syndesmophytes (solid white arrows). Progressive ossification connecting adjacent vertebral bodies produces the bamboo-spine appearance seen in this case, which is characteristic of ankylosing spondylitis.

Infectious Arthritis

Infectious arthritis usually occurs as a result of hematogenous seeding of the synovial membrane from an infected source elsewhere in the body, such as a wound infection or from direct, contiguous extension from osteomyelitis adjacent to the joint.

Infectious arthritis usually occurs as a result of hematogenous seeding of the synovial membrane from an infected source elsewhere in the body, such as a wound infection or from direct, contiguous extension from osteomyelitis adjacent to the joint. It is usually subdivided into pyogenic (septic) arthritis, due mostly to Staphylococcal and Gonococcal organisms and nonpyogenic arthritis, due mostly to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

It is usually subdivided into pyogenic (septic) arthritis, due mostly to Staphylococcal and Gonococcal organisms and nonpyogenic arthritis, due mostly to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Risk factors include intravenous drug use, steroid injections or oral administration, joint prostheses, and recent joint trauma, including joint surgery.

Risk factors include intravenous drug use, steroid injections or oral administration, joint prostheses, and recent joint trauma, including joint surgery.

Although conventional radiographs are obtained as the initial study, they are relatively insensitive to the early findings of the disease except for soft tissue swelling and osteopenia.

Although conventional radiographs are obtained as the initial study, they are relatively insensitive to the early findings of the disease except for soft tissue swelling and osteopenia.

![]() The hallmark of infectious arthritis, especially the pyogenic form, is destruction of the articular cartilage and long, contiguous segments of the adjacent articular cortex from proteolytic enzymes released by the inflamed synovium.

The hallmark of infectious arthritis, especially the pyogenic form, is destruction of the articular cartilage and long, contiguous segments of the adjacent articular cortex from proteolytic enzymes released by the inflamed synovium.

Infectious arthritis tends to be monoarticular and is associated with soft tissue swelling and osteopenia from the hyperemia of inflammation (Fig. 23-21).

Infectious arthritis tends to be monoarticular and is associated with soft tissue swelling and osteopenia from the hyperemia of inflammation (Fig. 23-21). Because of its sensitivity, MRI is now used extensively after conventional radiography in diagnosing septic joints. Enhancement of the synovium and the presence of a joint effusion have the best correlation with the clinical diagnosis of a septic joint.

Because of its sensitivity, MRI is now used extensively after conventional radiography in diagnosing septic joints. Enhancement of the synovium and the presence of a joint effusion have the best correlation with the clinical diagnosis of a septic joint. Nonpyogenic infectious arthritis is most often caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which spreads via the bloodstream from the lungs.

Nonpyogenic infectious arthritis is most often caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which spreads via the bloodstream from the lungs. Unlike pyogenic arthritis, tuberculous arthritis has an indolent and protracted course resulting in gradual loss of the joint space and late destruction of the articular cortex.

Unlike pyogenic arthritis, tuberculous arthritis has an indolent and protracted course resulting in gradual loss of the joint space and late destruction of the articular cortex. Nonpyogenic infectious arthritis is usually monarticular. Severe osteoporosis is a common finding. In children, the spine is most often affected; in adults, the knee.

Nonpyogenic infectious arthritis is usually monarticular. Severe osteoporosis is a common finding. In children, the spine is most often affected; in adults, the knee. Healing with fibrous and bony ankylosis occurs in both pyogenic and nonpyogenic infectious arthritis.

Healing with fibrous and bony ankylosis occurs in both pyogenic and nonpyogenic infectious arthritis.

Figure 23-21 Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, middle finger.

The hallmark of infectious arthritis, especially the pyogenic form, is destruction of the articular cartilage and long contiguous segments of the adjacent articular cortex from proteolytic enzymes released by the inflamed synovium. This patient has septic arthritis (the distal interphalangeal joint is destroyed) which has extended to the subjacent bone as osteomyelitis and destroyed either side of the joint space as well (solid and dotted white arrows). The time course of septic arthritis, unlike other arthritides, is usually quite rapid. This infection was the result of a human bite.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Joint Disease: An Approach to Arthritis on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Joint Disease: An Approach to Arthritis

An arthritis is a disease of a joint that invariably leads to joint space narrowing and changes to the bones on both sides of the joint.

Arthritides can be roughly divided into hypertrophic, infectious, and erosive (inflammatory) categories.

Hypertrophic arthritis features subchondral sclerosis, marginal osteophyte production, and subchondral cyst formation.

Primary osteoarthritis, the most common form of arthritis, is a type of hypertrophic arthritis. It typically occurs on weight-bearing surfaces of the hip and knee and the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers.

Other hypertrophic arthritides include CPPD, Charcot joints, and osteoarthritis secondary to prior trauma, AVN, or superimposed on another underlying arthritis.

Pyrophosphate arthropathy (CPPD) occurs with the deposition of calcium pyrophosphate crystals (chondrocalcinosis). It can produce large and multiple subchondral cysts, narrowing of the patellofemoral joint space, metacarpal hooks, and proximal migration of the distal carpal row.

Charcot or neuropathic joints feature fragmentation, sclerosis, and soft tissue swelling. Diabetes is the most frequent cause of a Charcot joint.

Erosive (or inflammatory) arthritis is associated with inflammation and synovial proliferation (pannus formation) which produces lytic lesions in or near the joint called erosions.

Rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and psoriasis are three examples of erosive arthritis; the site of involvement is helpful in differentiating among the causes of erosive arthritides.

Rheumatoid arthritis affects the carpals and proximal joints of the hand, can widen the predentate space in the cervical spine, and produces fusion of the posterior elements in the cervical spine.

Gout most often affects the metatarsal-phalangeal joint of the great toe with juxtaarticular erosions and little or no osteoporosis. Tophi are late manifestations of the disease and usually do not calcify.

Psoriatic arthritis usually occurs in patients with known skin changes and affects the distal joints primarily in the hands producing characteristic erosions that resemble a pencil in cup.

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic and progressive arthritis characterized by symmetric fusion of the SI joints and ascending involvement of the spine eventually producing a bamboo-spine appearance.

Infectious arthritis features soft tissue swelling and osteopenia and, in the case of pyogenic arthritis, relatively early and marked destruction of most or all of the articular cortex. It is due mostly to staphylococcal and gonococcal organisms.