Chapter 25 Recognizing Some Common Causes of Intracranial Pathology

Advances in neuroimaging have had a remarkable impact on the diagnosis and treatment of neurologic diseases ranging from earlier detection and treatment of stroke to a more timely diagnosis of dementia, from the rapid detection and treatment of cerebral aneurysms to the ability to diagnose multiple sclerosis after a single attack.

Advances in neuroimaging have had a remarkable impact on the diagnosis and treatment of neurologic diseases ranging from earlier detection and treatment of stroke to a more timely diagnosis of dementia, from the rapid detection and treatment of cerebral aneurysms to the ability to diagnose multiple sclerosis after a single attack. Both CT and MRI are utilized for studying the brain and spinal cord, but MRI is the study of first choice for most clinical scenarios (Table 25-1). Conventional radiography has no significant role in imaging intracranial abnormalities.

Both CT and MRI are utilized for studying the brain and spinal cord, but MRI is the study of first choice for most clinical scenarios (Table 25-1). Conventional radiography has no significant role in imaging intracranial abnormalities.TABLE 25-1 IMAGING STUDIES OF THE BRAIN FOR SELECTED ABNORMALITIES

| Abnormality | Study of First Choice | Other Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Acute stroke | Diffusion-weighted MR imaging for acute or small strokes, if available | Noncontrast CT can differentiate hemorrhagic from ischemic infarct |

| Headache, acute and severe | Noncontrast CT to detect subarachnoid hemorrhage | MR-angiography (MRA) or CT-angiography (CTA) if subarachnoid hemorrhage is found |

| Headaches, chronic | MRI without and with contrast | CT without and with contrast can be substituted |

| Seizures | MRI without and with contrast | CT without and with contrast can be substituted if MRI not available |

| Blood | Noncontrast CT | Ultrasound for infants |

| Head trauma | Nonenhanced CT is readily available and the study of first choice in head trauma | MRI is better at detecting diffuse axonal injury but requires more time and is not always available |

| Extracranial carotid disease | Doppler ultrasonography | MRA excellent study |

| Hydrocephalus | MRI as initial study | CT for follow-up |

| Vertigo and dizziness | Contrast-enhanced MRI | MRA if needed |

| Masses | Contrast-enhanced MRI | Contrast-enhanced CT if MRI not available |

| Change in mental status | MRI without or with contrast | CT without contrast is equivalent |

Normal Anatomy

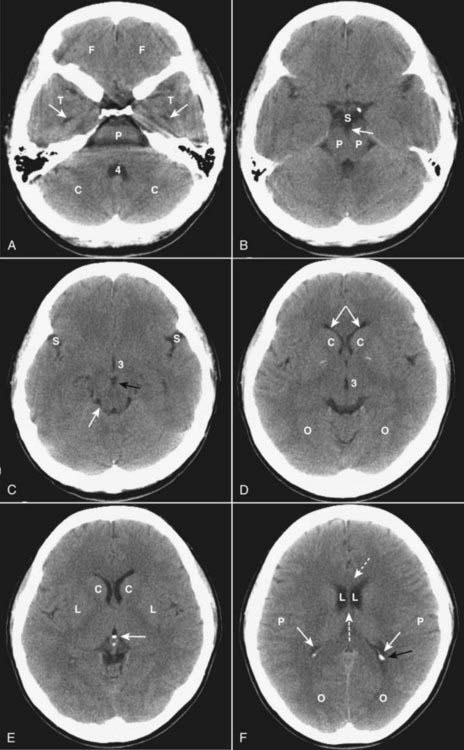

In the posterior fossa, the 4th ventricle appears as an inverted U-shaped structure. Like all cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing structures, it normally appears black. Superior to the 4th ventricle are the cerebellar hemispheres, inferiorly lie the pons and medulla oblongata. The tentorium cerebelli separates the infratentorial components of the posterior fossa (medulla, pons, cerebellum, and 4th ventricle) from the supratentorial compartment.

In the posterior fossa, the 4th ventricle appears as an inverted U-shaped structure. Like all cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing structures, it normally appears black. Superior to the 4th ventricle are the cerebellar hemispheres, inferiorly lie the pons and medulla oblongata. The tentorium cerebelli separates the infratentorial components of the posterior fossa (medulla, pons, cerebellum, and 4th ventricle) from the supratentorial compartment. The interpeduncular cistern lies in the midbrain and separates the paired cerebral peduncles (which emerge from the superior surface of the pons). The suprasellar cistern is anterior to the interpeduncular cistern and usually has a five-point or six-point starlike appearance.

The interpeduncular cistern lies in the midbrain and separates the paired cerebral peduncles (which emerge from the superior surface of the pons). The suprasellar cistern is anterior to the interpeduncular cistern and usually has a five-point or six-point starlike appearance. The sylvian fissures are bilaterally symmetrical and contain CSF. They separate the temporal from the frontal and parietal lobes.

The sylvian fissures are bilaterally symmetrical and contain CSF. They separate the temporal from the frontal and parietal lobes. The lentiform nucleus is composed of the putamen (laterally) and globus pallidus (medially). The 3rd ventricle is slitlike and midline. At the posterior aspect of the 3rd ventricle is the pineal gland. Farther posterior is the quadrigeminal plate cistern.

The lentiform nucleus is composed of the putamen (laterally) and globus pallidus (medially). The 3rd ventricle is slitlike and midline. At the posterior aspect of the 3rd ventricle is the pineal gland. Farther posterior is the quadrigeminal plate cistern. The corpus callosum connects the right and left cerebral hemispheres and forms the roof of the lateral ventricle. The anterior end is called the genu and the posterior end is called the splenium.

The corpus callosum connects the right and left cerebral hemispheres and forms the roof of the lateral ventricle. The anterior end is called the genu and the posterior end is called the splenium. The basal ganglia are represented by the subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra, globus pallidus, putamen, and caudate nucleus. The putamen and caudate nucleus are called the striatum.

The basal ganglia are represented by the subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra, globus pallidus, putamen, and caudate nucleus. The putamen and caudate nucleus are called the striatum. The frontal horns of the lateral ventricles hug the head of the caudate nucleus. The two frontal horns are separated by the midline septum pellucidum. The temporal horns, which are normally very small, are more inferior and contained in the temporal lobes. The posterior horns of the lateral ventricle (occipital horns) lie in the occipital lobes. The most superior portion of the ventricular system is formed by the bodies of the lateral ventricles.

The frontal horns of the lateral ventricles hug the head of the caudate nucleus. The two frontal horns are separated by the midline septum pellucidum. The temporal horns, which are normally very small, are more inferior and contained in the temporal lobes. The posterior horns of the lateral ventricle (occipital horns) lie in the occipital lobes. The most superior portion of the ventricular system is formed by the bodies of the lateral ventricles. The falx cerebri lies in the interhemispheric fissure, which separates the two cerebral hemispheres, and is frequently calcified in adults.

The falx cerebri lies in the interhemispheric fissure, which separates the two cerebral hemispheres, and is frequently calcified in adults. The surface or cortex of the brain is made up of gray matter convolutions, which in turn are composed of sulci (grooves) and gyri (elevations). The medullary white matter lies below the cortex.

The surface or cortex of the brain is made up of gray matter convolutions, which in turn are composed of sulci (grooves) and gyri (elevations). The medullary white matter lies below the cortex.

Figure 25-1 Normal unenhanced CT scans of the head.

A, Frontal lobes (F); temporal lobes (T); temporal horns (solid white arrows); fourth ventricle (4); cerebellum (C); pons (P). B, Suprasellar cistern (S); cerebral peduncles (P); interpeduncular cistern (solid white arrow). C, Sylvian fissures (S); 3rd ventricle (3); interpeduncular cistern (solid black arrow); quadrigeminal plate cistern (solid white arrow). D, Anterior horns of the lateral ventricles (solid white arrows); caudate nuclei (C); 3rd ventricle (3); occipital lobes (O). E, Caudate nuclei (C); lentiform nuclei (L); calcified pineal gland (solid white arrow). F, Genu of corpus callosum (dotted white arrow); lateral ventricles (L); septum pellucidum (dashed white arrow); parietal lobes (P); occipital horn (solid black arrow); calcified choroid plexus (solid white arrows); occipital lobes (O).

![]() On an unenhanced CT scan of the brain, anything that appears “white” will generally either be bone (calcium) density or blood in the absence of a metallic foreign body (Table 25-2).

On an unenhanced CT scan of the brain, anything that appears “white” will generally either be bone (calcium) density or blood in the absence of a metallic foreign body (Table 25-2).

Metallic densities in the head can cause artifacts on CT scans. Dental fillings, aneurysm clips, and bullets can all cause streak artifacts.

Metallic densities in the head can cause artifacts on CT scans. Dental fillings, aneurysm clips, and bullets can all cause streak artifacts.| Hypodense (Dark) (AKA Hypointense) | Isodense | Hyperdense (Bright) (AKA Hyperintense) |

|---|---|---|

| Fat (not usually present in the head) Air (e.g., sinuses) Water (e.g., CSF) |

Normal brain Some forms of protein (e.g., subacute subdural hematomas) |

Metal (e.g., aneurysm clips or bullets) Iodine (after contrast administration) Calcium Hemorrhage (high protein) |

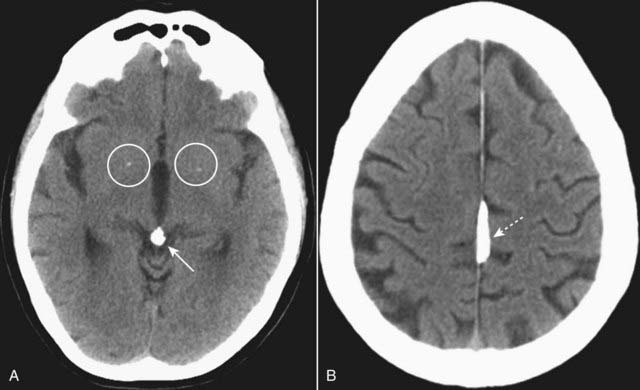

Figure 25-2 Physiologic calcifications.

A, There are small, punctate calcifications in the basal ganglia (white circles) and calcification of the pineal gland (solid white arrow). B, Calcification of the falx cerebri is present (dotted white arrow). Anything that appears white on a noncontrast enhanced CT of the brain is either calcium or blood. Physiologic calcifications tend to increase in incidence with advancing age.

Mri and the Brain

![]() In general, MRI is the study of choice for detecting and staging intracranial and spinal cord abnormalities. It is usually more sensitive than CT because of its superior contrast and soft tissue resolution. It is, however, less sensitive than CT in detecting calcification in lesions and cortical bone, which appear as signal voids with MR. It cannot be used in patients with pacemakers.

In general, MRI is the study of choice for detecting and staging intracranial and spinal cord abnormalities. It is usually more sensitive than CT because of its superior contrast and soft tissue resolution. It is, however, less sensitive than CT in detecting calcification in lesions and cortical bone, which appear as signal voids with MR. It cannot be used in patients with pacemakers.

MRI is more difficult to interpret because the same structure or abnormality will appear differently depending on the pulse sequence, the scan parameters, and the fact that MRI is more variable in its depiction of differences which occur over the time course of some abnormalities (e.g., hemorrhage) than is CT.

MRI is more difficult to interpret because the same structure or abnormality will appear differently depending on the pulse sequence, the scan parameters, and the fact that MRI is more variable in its depiction of differences which occur over the time course of some abnormalities (e.g., hemorrhage) than is CT. Initial evaluation of an MRI of the brain might start with the T1-weighted sagittal view of the brain. On this view the brain looks more like the anatomic specimens or diagrams you are accustomed to looking at (Fig. 25-3). We are fortunate that many structures in the brain are paired, so don’t forget to compare one side to the other on axial scans of the brain (Fig. 25-4).

Initial evaluation of an MRI of the brain might start with the T1-weighted sagittal view of the brain. On this view the brain looks more like the anatomic specimens or diagrams you are accustomed to looking at (Fig. 25-3). We are fortunate that many structures in the brain are paired, so don’t forget to compare one side to the other on axial scans of the brain (Fig. 25-4).

Figure 25-3 Normal midline MRI.

Sagittal T1-weighted close-up image demonstrates the midline structures of the brain. For orientation purposes, anterior is to your left (A). The corpus callosum (CC) is located superiorly. The pituitary gland (P) sits in the sella turcica and connects to the hypothalamus via the pituitary stalk or infundibulum (dotted white arrow). The mamillary bodies (M) are located anterior to the brain stem. The cerebral aqueduct (solid white arrow) is superior to the midbrain. The brain stem is composed of the midbrain (Mi), the pons (Po), and the medulla (Me). The 4th ventricle (4) communicates with the cerebral aqueduct and lies between the cerebellum (Ce) and the brain stem.

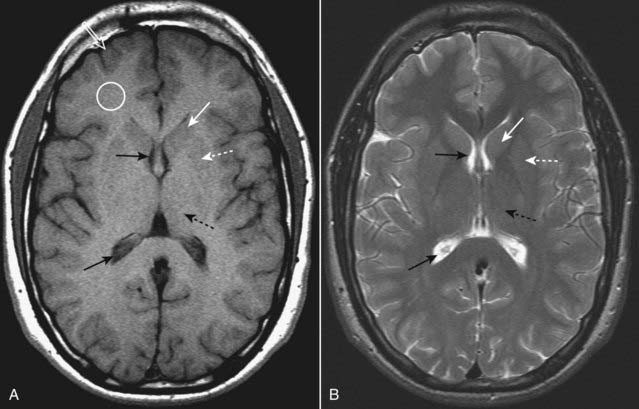

Figure 25-4 Normal MRI of the brain, T1 and T2.

Axial T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) images of the brain demonstrate that CSF in the lateral ventricles is dark on T1 and bright on T2 (solid black arrows). Gray matter, which contains the neuronal cell bodies, is actually gray on T1-weighted images (open white arrow), and white matter, which contains myelinated axon tracts, is whiter (white circle). The caudate nuclei (solid white arrows) and lentiform nucleus (dotted white arrows) together form the basal ganglia. The thalamus (dotted black arrows) is located posterior to the basal ganglia.

Head Trauma

Traumatic brain injuries extract a huge cost to the patient and society, not only as a result of the acute injury but also for the long-term disability they produce. In the United States, motor vehicle accidents account for nearly half of traumatic brain injuries.

Traumatic brain injuries extract a huge cost to the patient and society, not only as a result of the acute injury but also for the long-term disability they produce. In the United States, motor vehicle accidents account for nearly half of traumatic brain injuries. Unenhanced CT is the study of choice in acute head trauma. The primary goal in obtaining the scan is to determine if there is a life-threatening, but treatable, lesion.

Unenhanced CT is the study of choice in acute head trauma. The primary goal in obtaining the scan is to determine if there is a life-threatening, but treatable, lesion.

![]() Initial CT evaluation of the brain in the emergency setting focuses on whether there is mass effect or blood.

Initial CT evaluation of the brain in the emergency setting focuses on whether there is mass effect or blood.

To determine if there is mass effect, look for a displacement or compression of key structures from their normal positions by analyzing the location and appearance of the ventricles, basal cisterns and the sulci.

To determine if there is mass effect, look for a displacement or compression of key structures from their normal positions by analyzing the location and appearance of the ventricles, basal cisterns and the sulci. Blood will usually be hyperintense (bright) and might collect in the basal cisterns, sylvian and interhemispheric fissures, ventricles, the subdural or epidural spaces, or in the brain parenchyma (intracerebral).

Blood will usually be hyperintense (bright) and might collect in the basal cisterns, sylvian and interhemispheric fissures, ventricles, the subdural or epidural spaces, or in the brain parenchyma (intracerebral).Skull Fractures

Skull fractures are usually produced by direct impact to the skull and they most often occur at the point of impact. They are important primarily because their presence implies a force substantial enough to cause intracranial injury.

Skull fractures are usually produced by direct impact to the skull and they most often occur at the point of impact. They are important primarily because their presence implies a force substantial enough to cause intracranial injury. In order to visualize skull fractures, you must view the CT scan using the “bone window” settings that optimize visualization of the osseous structures (Fig. 25-5).

In order to visualize skull fractures, you must view the CT scan using the “bone window” settings that optimize visualization of the osseous structures (Fig. 25-5). Skull fractures can be described as linear, depressed, or basilar.

Skull fractures can be described as linear, depressed, or basilar.

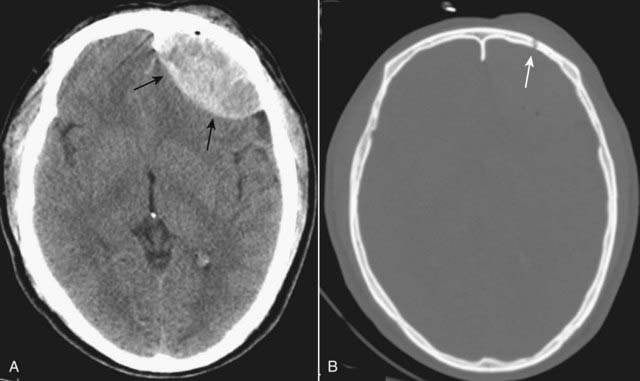

Figure 25-5 CT, “brain” and “bone” windows.

In order to visualize skull fractures, you must view the CT scan using the “bone” windows. A, Using the “brain window,” a lenticular-shaped, hyperintense lesion is seen in the left frontal region displaying the typical appearance of an epidural hematoma (solid black arrows). B, Viewing the same scan at the “bone window” setting shows a fracture (solid white arrow) of the left frontal bone at the site of the epidural hematoma.

A, There is a depressed fracture of the right parietal bone with the fragment lying deeper than the inner table of the adjacent bone (solid white arrow). Depressed skull fractures occur more often in the frontoparietal region. B, On this close-up axial CT of the mastoids, there is a comminuted fracture of the right temporal bone (solid white arrows), fluid in the mastoid air cells (white circle), and air in the brain (pneumocephalus) (dotted white arrow). Basilar skull fractures can be associated with tears in the dura mater with subsequent CSF leak. (A = Anterior.)

![]() Basilar skull fractures are the most serious and consist of a linear fracture at the base of the skull. They can be associated with tears in the dura mater with subsequent CSF leak, which can lead to CSF rhinorrhea and otorrhea. They can be suspected if there is air seen in the brain (traumatic pneumocephalus), fluid in the mastoid air cells, or an air-fluid level in the sphenoid sinus (Fig. 25-6B).

Basilar skull fractures are the most serious and consist of a linear fracture at the base of the skull. They can be associated with tears in the dura mater with subsequent CSF leak, which can lead to CSF rhinorrhea and otorrhea. They can be suspected if there is air seen in the brain (traumatic pneumocephalus), fluid in the mastoid air cells, or an air-fluid level in the sphenoid sinus (Fig. 25-6B).

Facial Fractures

CT is the imaging study of choice for evaluating facial fractures. Multislice scanners allow for reconstruction in the coronal plane so the patient does not have to be repositioned in the scanner.

CT is the imaging study of choice for evaluating facial fractures. Multislice scanners allow for reconstruction in the coronal plane so the patient does not have to be repositioned in the scanner.

![]() Care must be taken in diagnosing facial fractures based upon viewing what appears to be a fracture on only one image since CT scans, by their nature, produce sections so thin, they may not demonstrate the entire contour of the bone in question. Look for a fracture to appear on several contiguous images.

Care must be taken in diagnosing facial fractures based upon viewing what appears to be a fracture on only one image since CT scans, by their nature, produce sections so thin, they may not demonstrate the entire contour of the bone in question. Look for a fracture to appear on several contiguous images.

The most common orbital fracture is the blow-out fracture, which is produced by a direct impact on the orbit (e.g., a baseball strikes the eye) that causes a sudden increase in intraorbital pressure leading to a fracture of the inferior orbital floor (into the maxillary sinus) or the medial wall of the orbit (into the ethmoid sinus). Sometimes, the inferior rectus muscle can be trapped in the fracture leading to restriction of upward gaze and diplopia.

The most common orbital fracture is the blow-out fracture, which is produced by a direct impact on the orbit (e.g., a baseball strikes the eye) that causes a sudden increase in intraorbital pressure leading to a fracture of the inferior orbital floor (into the maxillary sinus) or the medial wall of the orbit (into the ethmoid sinus). Sometimes, the inferior rectus muscle can be trapped in the fracture leading to restriction of upward gaze and diplopia. Recognizing a blow-out fracture of the orbit (Fig. 25-7A).

Recognizing a blow-out fracture of the orbit (Fig. 25-7A).

A tripod fracture, usually a result of blunt force to the cheek, is another relatively common facial fracture. This fracture involves separation of the zygoma from the remainder of the face by separation of the frontozygomatic suture, fracture of the floor of the orbit, and fracture of the lateral wall of the ipsilateral maxillary sinus (Fig. 25-7B).

A tripod fracture, usually a result of blunt force to the cheek, is another relatively common facial fracture. This fracture involves separation of the zygoma from the remainder of the face by separation of the frontozygomatic suture, fracture of the floor of the orbit, and fracture of the lateral wall of the ipsilateral maxillary sinus (Fig. 25-7B).

Figure 25-7 Facial bone fractures.

A, Blow-out fracture. Air is demonstrated in the left orbit representing orbital emphysema (black circle). A fracture of the floor of the orbit is seen, and soft tissue (in this case, fat) extends inferiorly into the top of the maxillary sinus (solid white arrow). B, Tripod fracture. There is diastasis of the frontozygomatic suture on the left (dotted white arrow), a fracture of the floor of the orbit with orbital emphysema (dashed white arrow), and a fracture (solid white arrow) through the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus (M), which is filled with blood.

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Epidural Hematoma (Extradural Hematoma)

Epidural hematomas represent hemorrhage into the potential space between the dura mater and the inner table of the skull (Table 25-4).

Epidural hematomas represent hemorrhage into the potential space between the dura mater and the inner table of the skull (Table 25-4). Most cases are due to injury to the middle meningeal artery or vein from blunt head trauma, typically from a motor vehicle accident.

Most cases are due to injury to the middle meningeal artery or vein from blunt head trauma, typically from a motor vehicle accident.

| Layer | Comments |

|---|---|

| Dura mater | Composed of two layers, an outer periosteal layer which cannot be separated from the skull and an inner meningeal layer; the inner meningeal layer enfolds to form the tentorium and falx. |

| Arachnoid | The avascular middle layer, it is separated from the dura by a potential space known as the subdural space. |

| Pia mater | Closely applied to the brain and spinal cord, the pia mater carries blood vessels that supply both; separating the arachnoid from the pia is the subarachnoid space; together the pia and arachnoid are called the leptomeninges. |

![]() Almost all epidural hematomas (95%) have an associated skull fracture, frequently in the temporal bone. Epidural hematomas may also be caused by disruption of the dural venous sinuses adjacent to a skull fracture.

Almost all epidural hematomas (95%) have an associated skull fracture, frequently in the temporal bone. Epidural hematomas may also be caused by disruption of the dural venous sinuses adjacent to a skull fracture.

Recognizing an epidural hematoma

Recognizing an epidural hematoma

Figure 25-8 Epidural hematoma.

Acute epidural hematomas usually occur as a result of a trauma-induced skull fracture. Findings include a high-density, extraaxial, biconvex, lens-shaped mass lesion often found in the temporal-parietal region of the brain (solid black arrow). There is a scalp hematoma (solid white arrow) also present. The patient had a temporal bone skull fracture seen on bone windows.

Subdural Hematoma (SDH)

Subdural hematomas are more common than epidural hematomas and are usually not associated with a skull fracture. They are most commonly a result of deceleration injuries in motor vehicle or motorcycle accidents (younger patients) or secondary to falls (older patients).

Subdural hematomas are more common than epidural hematomas and are usually not associated with a skull fracture. They are most commonly a result of deceleration injuries in motor vehicle or motorcycle accidents (younger patients) or secondary to falls (older patients). Subdural hematomas are usually produced by damage to the bridging veins that cross from the cerebral cortex to the venous sinuses of the brain. They represent hemorrhage into the potential space between the dura mater and the arachnoid.

Subdural hematomas are usually produced by damage to the bridging veins that cross from the cerebral cortex to the venous sinuses of the brain. They represent hemorrhage into the potential space between the dura mater and the arachnoid.

![]() Acute subdural hematomas frequently herald the presence of more severe parenchymal brain injury and increased intracranial pressure and are associated with a higher mortality rate.

Acute subdural hematomas frequently herald the presence of more severe parenchymal brain injury and increased intracranial pressure and are associated with a higher mortality rate.

Recognizing an acute subdural hematoma

Recognizing an acute subdural hematoma

Chronic subdural hematoma

Chronic subdural hematoma

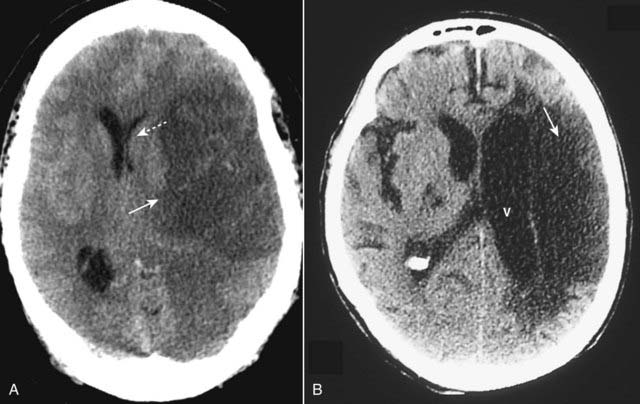

Figure 25-9 Acute, isodense, and chronic subdural hematomas.

A, There is a crescent-shaped band of high-density blood concave inward towards the brain (solid white arrow). Mass effect is present with herniation of the brain as indicated by the dilated contralateral temporal horn (dotted white arrow). B, As they become subacute, subdural hematomas become less dense and may be the same density (isodense) as the normal brain tissue (solid white arrow). You can recognize an isodense subdural by the unilateral absence or displacement of the sulci away from the inner table of the skull compared to the normal opposite side (solid black arrow). C, Chronic subdural hematomas (more than 3 weeks old) are usually of low density (solid white arrow) compared to the remainder if the brain. There is still mass effect demonstrated by displacement of the interhemispheric fissure (dotted white arrow) and compression of the lateral ventricle.

Intracerebral Hematoma (Intracerebral Hemorrhage)

Trauma is only one of the mechanisms that can lead to intracerebral hemorrhage. Intracerebral hematomas can also occur from ruptures of aneurysms, atheromatous disease in small vessels, or vasculitis.

Trauma is only one of the mechanisms that can lead to intracerebral hemorrhage. Intracerebral hematomas can also occur from ruptures of aneurysms, atheromatous disease in small vessels, or vasculitis. Injuries occurring at the point of impact (called coup injuries) and injuries occurring opposite the point of impact (called contrecoup injuries) are most common following trauma. Coup injuries are most often due to shearing of small intracerebral vessels. Contrecoup injuries are acceleration/deceleration injuries that occur when the brain is propelled in the opposite direction and strikes the inner surface of the skull.

Injuries occurring at the point of impact (called coup injuries) and injuries occurring opposite the point of impact (called contrecoup injuries) are most common following trauma. Coup injuries are most often due to shearing of small intracerebral vessels. Contrecoup injuries are acceleration/deceleration injuries that occur when the brain is propelled in the opposite direction and strikes the inner surface of the skull.

![]() Either of these mechanisms can produce a cerebral contusion. Contusions are hemorrhages with associated edema usually found in the inferior frontal lobes and temporal lobes on or near the surface of the brain (Fig. 25-10).

Either of these mechanisms can produce a cerebral contusion. Contusions are hemorrhages with associated edema usually found in the inferior frontal lobes and temporal lobes on or near the surface of the brain (Fig. 25-10).

CT findings of intracerebral hemorrhage change over time and may not be immediately evident on the initial scan. MRI typically demonstrates the lesions from the time of injury, but may not be available on an emergency basis.

CT findings of intracerebral hemorrhage change over time and may not be immediately evident on the initial scan. MRI typically demonstrates the lesions from the time of injury, but may not be available on an emergency basis. Recognizing traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage on CT

Recognizing traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage on CT

Figure 25-10 Cerebral contusions.

A, Cerebral contusions are usually the result of trauma and can manifest by multiple areas of high attenuation hemorrhage (solid white arrows) within the brain parenchyma on CT. B, Contusions (solid black arrow) are frequently surrounded by a rim of hypoattenuation from edema (dotted black arrow), and mass effect is common, as is demonstrated here by amputation of the ipsilateral basilar cisterns (dotted white arrow), midline displacement (solid white arrow) representing subfalcine herniation, and dilatation of the contralateral temporal horn (white circle). A portion of the left side of the skull has been surgically removed, and there is a large scalp hematoma present (dashed white arrow).

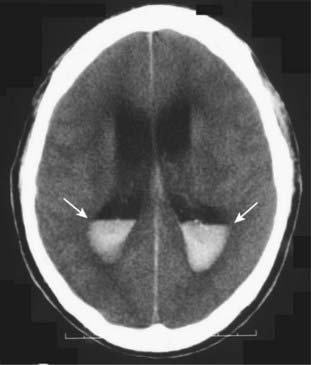

Figure 25-11 Intraventricular hemorrhage.

Intraventricular hemorrhage (solid white arrows) is common in premature infants but less common in adults. It usually results from break-through bleeding from a brain contusion or subarachnoid hemorrhage and requires a considerable amount of force to produce. Therefore, it is typically associated with severe brain damage and has a poor prognosis.

TABLE 25-5 TYPES OF BRAIN HERNIATION

| Type | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Subfalcine herniation | The supratentorial brain, along with the lateral ventricle and septum pellucidum, herniates beneath the falx and shifts across the midline toward the opposite side (see Fig. 25-12A). |

| Transtentorial herniation | Usually, the cerebral hemispheres are displaced downward through the incisura beneath the tentorium compressing the ipsilateral temporal horn and causing dilatation of the contralateral temporal horn (see Fig. 25-12B). |

| Foramen magnum/tonsillar herniation | Infratentorial brain is displaced downward through the foramen magnum. |

| Sphenoid herniation | Supratentorial brain slides over the sphenoid bone either anteriorly (in the case of the temporal lobe) or posteriorly (for the frontal lobe). |

| Extracranial herniation | Displacement of brain through a defect in the cranium. |

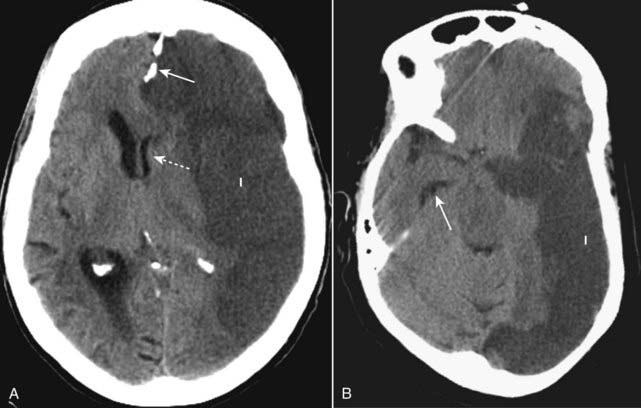

Figure 25-12 Brain herniations.

A, Subfalcine herniation occurs when the supratentorial brain, along with the lateral ventricle and septum pellucidum, herniate beneath the falx (solid white arrow) and shift across the midline toward the opposite side (dotted white arrow). B, Transtentorial herniation usually occurs when the cerebral hemispheres are displaced downward through the incisura beneath the tentorium compressing the ipsilateral temporal horn and causing dilatation of the contralateral temporal horn (solid white arrow). Both patients had large cerebral infarcts (I) with cytotoxic edema.

Diffuse Axonal Injury

Diffuse axonal injury is responsible for the prolonged coma following head trauma and is the head injury with the poorest prognosis.

Diffuse axonal injury is responsible for the prolonged coma following head trauma and is the head injury with the poorest prognosis. Acceleration/deceleration forces diffusely injure axons deep to the cortex producing unconsciousness from the moment of injury. This occurs most often as a result of a motor vehicle accident.

Acceleration/deceleration forces diffusely injure axons deep to the cortex producing unconsciousness from the moment of injury. This occurs most often as a result of a motor vehicle accident.

![]() The corpus callosum is most commonly affected, and the initial CT scan may be normal or underestimate the degree of injury. CT findings may be similar to those described for intracerebral hemorrhage following head trauma.

The corpus callosum is most commonly affected, and the initial CT scan may be normal or underestimate the degree of injury. CT findings may be similar to those described for intracerebral hemorrhage following head trauma.

MR is the study of choice in identifying diffuse axonal injury.

MR is the study of choice in identifying diffuse axonal injury.

Figure 25-13 Diffuse axonal injury, MRI.

These images were obtained using a pulse sequence similar to T2 but with suppression of the bright signal from CSF, which enhances areas of edema (that appear bright). (A) and (B) are axial images demonstrating multiple foci of abnormal increased signal at the gray-white matter junction (solid white arrows) and within the splenium of the corpus callosum (solid black arrow) in a patient with diffuse axonal injury.

Increased Intracranial Pressure

Some of the clinical signs of increased intracranial pressure are papilledema, headache, and diplopia.

Some of the clinical signs of increased intracranial pressure are papilledema, headache, and diplopia.

![]() In general, increased intracranial pressure is due to either cerebral edema, which leads to increased volume of the brain, or hydrocephalus, which is increased size of the ventricles.

In general, increased intracranial pressure is due to either cerebral edema, which leads to increased volume of the brain, or hydrocephalus, which is increased size of the ventricles.

Cerebral edema

Cerebral edema

Increased intracranial pressure secondary to increase in the size of the ventricles is discussed under Hydrocephalus.

Increased intracranial pressure secondary to increase in the size of the ventricles is discussed under Hydrocephalus.

Figure 25-14 Vasogenic and cytotoxic edema.

There are two major categories of cerebral edema: vasogenic (A) and cytotoxic (B). A, Vasogenic edema (solid white arrow) represents extracellular accumulation of fluid and is the type that occurs with infection and malignancy, as in this unenhanced scan of a patient with a glioma. It predominantly affects the white matter. B, Cytotoxic edema (solid white arrow) represents cellular edema and affects both the gray and white matter. Cytotoxic edema is associated with cerebral ischemia, as in this patient with a very large ischemic infarct on the right. In both of these patients, there is increased intracranial pressure as manifest by the herniation of brain to the contralateral side (dotted white arrows in both).

Stroke

General Considerations

Stroke is a nonspecific term that usually denotes an acute loss of neurologic function that occurs when the blood supply to an area of the brain is lost or compromised.

Stroke is a nonspecific term that usually denotes an acute loss of neurologic function that occurs when the blood supply to an area of the brain is lost or compromised.

![]() The diagnosis of stroke is usually a clinical diagnosis. Patients with suspected stroke are imaged to determine if there is another cause of the neurologic impairment besides a stroke (e.g., a brain tumor), to identify the presence of blood so as to distinguish ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke, which may determine whether or not thrombolytic therapy will be instituted, and to identify the infarct and characterize it.

The diagnosis of stroke is usually a clinical diagnosis. Patients with suspected stroke are imaged to determine if there is another cause of the neurologic impairment besides a stroke (e.g., a brain tumor), to identify the presence of blood so as to distinguish ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke, which may determine whether or not thrombolytic therapy will be instituted, and to identify the infarct and characterize it.

Most strokes are embolic in origin, the emboli arising from the internal carotid artery or the common carotid bifurcation. Emboli can also arise in the heart.

Most strokes are embolic in origin, the emboli arising from the internal carotid artery or the common carotid bifurcation. Emboli can also arise in the heart. The other common cause of stroke is thrombosis, representing in-situ occlusion of the carotid, vertebrobasilar, or intracerebral circulations from atheromatous lesions. Thrombosis of the middle cerebral artery is particularly common.

The other common cause of stroke is thrombosis, representing in-situ occlusion of the carotid, vertebrobasilar, or intracerebral circulations from atheromatous lesions. Thrombosis of the middle cerebral artery is particularly common. Strokes are divided into two large groups: ischemic or hemorrhagic. Ischemic strokes are much more common. The classification is important because rapid treatment of ischemic stroke with tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) or another form of intraarterial recanalization technique can substantially improve the prognosis.

Strokes are divided into two large groups: ischemic or hemorrhagic. Ischemic strokes are much more common. The classification is important because rapid treatment of ischemic stroke with tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) or another form of intraarterial recanalization technique can substantially improve the prognosis. Most acute strokes are initially imaged by obtaining a noncontrast enhanced CT scan of the brain (within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms), mostly because of its availability. CT findings may be present within hours after the onset of symptoms for ischemic stroke and immediately after a hemorrhagic stroke.

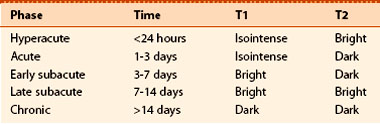

Most acute strokes are initially imaged by obtaining a noncontrast enhanced CT scan of the brain (within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms), mostly because of its availability. CT findings may be present within hours after the onset of symptoms for ischemic stroke and immediately after a hemorrhagic stroke. MR imaging has become more widely used for early diagnosis. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging is more sensitive and relatively specific for detecting early infarction with the capacity to detect changes within a few minutes of the onset of the event. On MRI, the temporal staging of hemorrhage can be identified based on chemical changes that occur in the hemoglobin molecule as the hemorrhage evolves (Fig. 25-16).

MR imaging has become more widely used for early diagnosis. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging is more sensitive and relatively specific for detecting early infarction with the capacity to detect changes within a few minutes of the onset of the event. On MRI, the temporal staging of hemorrhage can be identified based on chemical changes that occur in the hemoglobin molecule as the hemorrhage evolves (Fig. 25-16).

Figure 25-16 CT and diffusion-weighted MRI in acute stroke.

A, The CT scan in this patient with symptoms for 2 hours prior to the study is normal. B, A diffusion-weighted MRI scan on the same patient a few minutes later shows an area of abnormally bright signal intensity in the right parietal lobe (solid white arrow). Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is an MRI sequence that can be rapidly acquired and which is extremely sensitive to detecting abnormalities in normal water movement in the brain so that it can identify a stroke within minutes after the event.

Ischemic Stroke

Thromboembolic disease consequent to atherosclerosis is the most common cause of an ischemic stroke. The source of the emboli can be from atheromatous debris, arterial stenosis and occlusion, or from emboli arising from the left side of the heart (e.g., atrial fibrillation).

Thromboembolic disease consequent to atherosclerosis is the most common cause of an ischemic stroke. The source of the emboli can be from atheromatous debris, arterial stenosis and occlusion, or from emboli arising from the left side of the heart (e.g., atrial fibrillation). Vascular watershed areas are the distal arterial territories that represent the junctions between areas served by the major intracerebral vessels such as the region between the anterior cerebral artery distribution and the middle cerebral artery distribution. Reduction in blood flow, for whatever reason, affects these sensitive and susceptible watershed areas the most.

Vascular watershed areas are the distal arterial territories that represent the junctions between areas served by the major intracerebral vessels such as the region between the anterior cerebral artery distribution and the middle cerebral artery distribution. Reduction in blood flow, for whatever reason, affects these sensitive and susceptible watershed areas the most.

![]() The most common finding of an acute, nonhemorrhagic stroke is a normal CT scan (less than 24 hours old). If multiple vascular distributions are involved, emboli or vasculitis should be thought of as the cause. If the stroke crosses or falls between vascular territories, then hypoperfusion due to hypotension (watershed infarcts) should be considered.

The most common finding of an acute, nonhemorrhagic stroke is a normal CT scan (less than 24 hours old). If multiple vascular distributions are involved, emboli or vasculitis should be thought of as the cause. If the stroke crosses or falls between vascular territories, then hypoperfusion due to hypotension (watershed infarcts) should be considered.

Table 25-6 briefly summarizes the four major vascular distribution patterns of strokes and some of the symptoms associated with each.

Table 25-6 briefly summarizes the four major vascular distribution patterns of strokes and some of the symptoms associated with each. Recognizing ischemic stroke

Recognizing ischemic stroke

TABLE 25-6 VASCULAR DISTRIBUTION TERRITORIES OF STROKE

| Circulation | Anatomy Affected | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior cerebral artery (uncommon) | Supplies all of the frontal and parietal lobes (medial surfaces), the anterior four fifths of the corpus callosum, the frontobasal cerebral cortex, and the anterior diencephalon. | Can result in disinhibition and perseveration of speech; produces primitive reflexes (e.g., grasping or sucking), altered mental status, impaired judgment, contralateral weakness (greater in legs than arms). |

| Middle cerebral artery (common) | Supplies almost the entire convex surface of the brain including the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes (laterally), insula, claustrum, and extreme capsule. Lenticulostriate branches supply the basal ganglia, including the head of the caudate nucleus, the putamen including the lateral parts of the internal and external capsules. | Produces contralateral hemiparesis or hypesthesia, ipsilateral hemianopsia, and gaze preference toward the side of the lesion; agnosia is common; receptive or expressive aphasia may result if the lesion occurs in the dominant hemisphere; weakness of the arm and face is usually worse than that of the lower limb. |

| Posterior cerebral artery | Supplies portions of the midbrain, subthalamic nucleus, basal nucleus, thalamus, mesial inferior temporal lobe, and occipital and occipitoparietal cortices. | Occlusions affect vision and thought producing contralateral homonymous hemianopsia, cortical blindness, visual agnosia, altered mental status, and impaired memory. |

| Vertebrobasilar system | Perfuses the medulla, cerebellum, pons, midbrain, thalamus, and occipital cortex. | Occlusion of large vessels in this system usually leads to major disability or death; small lesions usually have a benign prognosis; may cause a wide variety of cranial nerve, cerebellar, and brain stem deficits; a hallmark of posterior circulation stroke is crossed findings: ipsilateral cranial nerve deficits and contralateral motor deficits (in contrast to anterior stroke). |

Figure 25-17 Ischemic stroke, newer and older.

The findings in ischemic stroke will depend on the amount of time that has elapsed since the original event. A, At about 24 hours, the lesion becomes relatively well circumscribed (solid white arrow) with mass effect evidenced by a shift of the ventricles (dotted white arrow) that peaks at 3 to 5 days and disappears by about 2 to 4 weeks. B, As the stroke matures, it loses its mass effect, tends to become an even more sharply marginated low attenuation lesion (solid white arrow), and may be associated with enlargement of the adjacent ventricle (V) due to loss of brain substance in the infarcted area.

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Hemorrhage occurs in about 15% of strokes. Hemorrhage is associated with a higher morbidity and mortality than ischemic stroke. Hemorrhage from stroke can occur into the brain parenchyma or the subarachnoid space.

Hemorrhage occurs in about 15% of strokes. Hemorrhage is associated with a higher morbidity and mortality than ischemic stroke. Hemorrhage from stroke can occur into the brain parenchyma or the subarachnoid space. In the majority of cases, there is associated hypertension. About 60% of hypertensive hemorrhages occur in the basal ganglia. Other areas commonly involved are the thalamus, pons, and cerebellum (Fig. 25-18).

In the majority of cases, there is associated hypertension. About 60% of hypertensive hemorrhages occur in the basal ganglia. Other areas commonly involved are the thalamus, pons, and cerebellum (Fig. 25-18).

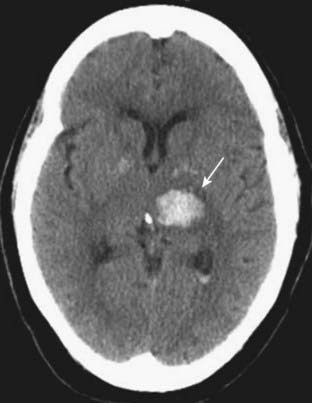

Figure 25-18 Intracerebral hemorrhage, acute.

Freshly extravasated whole blood, as this bleed into the thalamus (solid white arrow), will be visible as increased density on nonenhanced CT scans of the brain due primarily to the protein in the blood (mostly hemoglobin). As the clot begins to form, the blood becomes denser for about 3 days because of dehydration of the clot. After the third day, the clot gradually decreases in density from the outside in and becomes invisible over the next several weeks.

![]() The decision to utilize thrombolytic or another intraarterial recanalization therapy is based on algorithms formulated by the initial nonenhanced CT scan findings. The more rapidly treatment is initiated (usually less than 4 to 5 hours after the onset of symptoms), the greater its potential benefit.

The decision to utilize thrombolytic or another intraarterial recanalization therapy is based on algorithms formulated by the initial nonenhanced CT scan findings. The more rapidly treatment is initiated (usually less than 4 to 5 hours after the onset of symptoms), the greater its potential benefit.

Recognizing intracerebral hemorrhage (in general)

Recognizing intracerebral hemorrhage (in general)

On MRI, the changes in the appearance of hemorrhage over time are more dramatic. MRI is sensitive to changing effects in both the iron and protein portions of the hemoglobin molecule in the days and weeks following an acute bleed. Table 25-7 summarizes those changes.

On MRI, the changes in the appearance of hemorrhage over time are more dramatic. MRI is sensitive to changing effects in both the iron and protein portions of the hemoglobin molecule in the days and weeks following an acute bleed. Table 25-7 summarizes those changes.

A lacunar infarct, or lacune, is a small cerebral infarct produced by occlusion of an end artery. Lacunar infarcts have a predilection for the basal ganglia, internal capsule, and pons, primarily related to hypertension and atherosclerosis. The term lacunar infarct is reserved for low density, cystic lesions, 5 mm to 15 mm in size (solid white arrow).

Ruptured Aneurysms

The most frequent central nervous system aneurysm is the berry aneurysm, which develops from a congenital weakening in the arterial wall, usually at the sites of vessel branching in the circle of Willis at the base of the brain. They can be familial (about 10% of cases) or associated with connective tissue diseases.

The most frequent central nervous system aneurysm is the berry aneurysm, which develops from a congenital weakening in the arterial wall, usually at the sites of vessel branching in the circle of Willis at the base of the brain. They can be familial (about 10% of cases) or associated with connective tissue diseases. Hypertension and aging play a role in the growth of aneurysms. Larger aneurysms bleed more frequently than do smaller ones.

Hypertension and aging play a role in the growth of aneurysms. Larger aneurysms bleed more frequently than do smaller ones. The aim is to discover and treat the aneurysm before it has undergone a major bleed. In some studies, 10 mm was found to be the critical size for rupture.

The aim is to discover and treat the aneurysm before it has undergone a major bleed. In some studies, 10 mm was found to be the critical size for rupture. The classical history a patient describes who has had a ruptured aneurysm is “the worst headache of my life.”

The classical history a patient describes who has had a ruptured aneurysm is “the worst headache of my life.”

![]() When aneurysms rupture, the blood usually enters the subarachnoid space. Rupture of an aneurysm is the most common nontraumatic cause of a subarachnoid hemorrhage (80%) but not the only cause. Trauma, arteriovenous malformations, or breakthrough of an intraparenchymal bleed can also produce subarachnoid hemorrhage.

When aneurysms rupture, the blood usually enters the subarachnoid space. Rupture of an aneurysm is the most common nontraumatic cause of a subarachnoid hemorrhage (80%) but not the only cause. Trauma, arteriovenous malformations, or breakthrough of an intraparenchymal bleed can also produce subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Today, most aneurysms are detected by either CT angiography or MR angiography. CT angiography is performed using a power injector to deliver a rapid bolus intravenous injection of iodinated contrast, a CT scanner capable of rapid acquisition of data and special computer algorithms, and postprocessing techniques that can highlight the vessels and, if desired, display them three-dimensionally (Fig. 25-20).

Today, most aneurysms are detected by either CT angiography or MR angiography. CT angiography is performed using a power injector to deliver a rapid bolus intravenous injection of iodinated contrast, a CT scanner capable of rapid acquisition of data and special computer algorithms, and postprocessing techniques that can highlight the vessels and, if desired, display them three-dimensionally (Fig. 25-20). MR angiography can be done without any contrast, but is usually performed with the intravenous injection of MR contrast (gadolinium) and specialized computer algorithms that allow for highlighting the blood vessels being studied.

MR angiography can be done without any contrast, but is usually performed with the intravenous injection of MR contrast (gadolinium) and specialized computer algorithms that allow for highlighting the blood vessels being studied. Recognizing a subarachnoid hemorrhage (from a ruptured aneurysm)

Recognizing a subarachnoid hemorrhage (from a ruptured aneurysm)

Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage besides aneurysms include arteriovenous malformations, tumors, mycotic aneurysms, and amyloid angiopathy (Box 25-2).

Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage besides aneurysms include arteriovenous malformations, tumors, mycotic aneurysms, and amyloid angiopathy (Box 25-2).

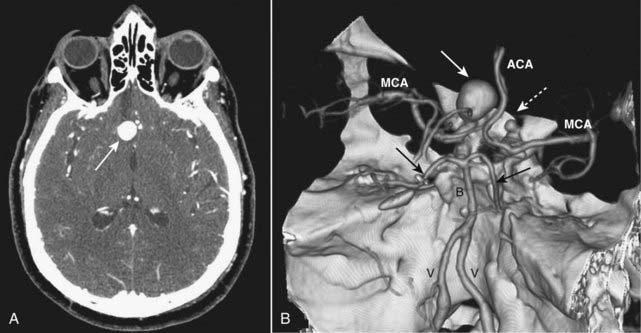

Figure 25-20 Berry aneurysm, axial CT and 3-D reconstruction.

A, There is a 2 cm focal outpouching of contrast in the region of the right internal carotid artery (ICA) on this contrast-enhanced CT of the brain (solid white arrow). This is consistent with an aneurysm. B, A 3-D reconstruction of the circle of Willis from a CT-angiogram demonstrates the aneurysm arising from the supraclinoid segment of the right ICA (solid white arrow) and another smaller aneurysm arising from the supraclinoid segment of the left ICA (dotted white arrow). V = vertebral artery; B = basilar artery; MCA = middle cerebral arteries; ACA = anterior cerebral arteries; solid black arrows point to posterior cerebral arteries.

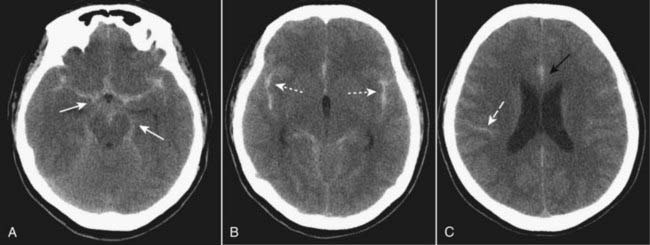

Figure 25-21 Subarachnoid hemorrhage, unenhanced CT scans.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is frequently the result of a ruptured aneurysm. Blood may be most easily visualized within the basal cisterns (solid white arrows in A), in the fissures (dotted white arrows in B), and interdigitated in the subarachnoid spaces of the sulci (dashed white arrow in C). The region of the falx may become hyperdense, widened, and irregularly marginated (solid black arrow in C).

Box 25-2 Amyloid Angiopathy

Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is defined as an expansion of the ventricular system on the basis of an increase in the volume of cerebrospinal fluid contained within it (Box 25-3).

Hydrocephalus is defined as an expansion of the ventricular system on the basis of an increase in the volume of cerebrospinal fluid contained within it (Box 25-3).

Box 25-3 Normal Flow of Cerebrospinal Fluid

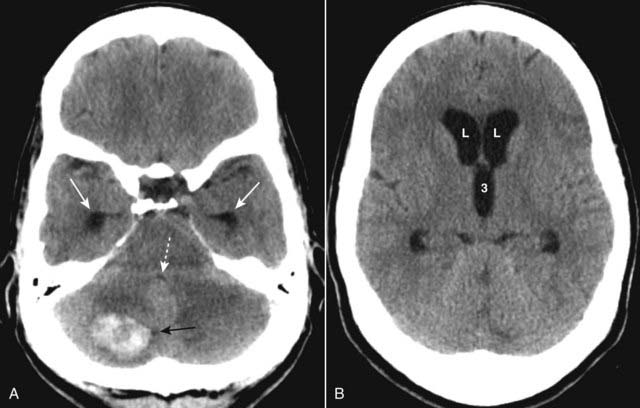

Restriction of the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid from the ventricles (noncommunicating hydrocephalus)

Restriction of the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid from the ventricles (noncommunicating hydrocephalus) In hydrocephalus, the ventricles are usually disproportionately dilated compared to the sulci, whereas both the ventricles and sulci are proportionately enlarged in cerebral atrophy.

In hydrocephalus, the ventricles are usually disproportionately dilated compared to the sulci, whereas both the ventricles and sulci are proportionately enlarged in cerebral atrophy. The temporal horns are particularly sensitive to increases in CSF pressure. In the absence of hydrocephalus, the temporal horns are barely visible. With hydrocephalus the temporal horns may be greater than 2 mm in size (Fig. 25-22).

The temporal horns are particularly sensitive to increases in CSF pressure. In the absence of hydrocephalus, the temporal horns are barely visible. With hydrocephalus the temporal horns may be greater than 2 mm in size (Fig. 25-22).

Figure 25-22 Noncommunicating hydrocephalus.

A, There is dilatation of the temporal horns (solid white arrows) and the 4th ventricle is compressed and nearly invisible (dotted white arrow). A hemorrhagic metastatic lesion (solid black arrow) is present that is obstructing the 4th ventricle. B, The frontal horns of the lateral ventricles (L) and 3rd ventricle (3) are dilated, but note that the sulci are not dilated. This form of hydrocephalus is the result of obstruction to the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid from the ventricles.

Obstructive Hydrocephalus

Obstructive hydrocephalus is divided into two major categories: communicating (extraventricular obstruction) and noncommunicating (intraventricular obstruction).

Obstructive hydrocephalus is divided into two major categories: communicating (extraventricular obstruction) and noncommunicating (intraventricular obstruction). Communicating hydrocephalus is due to abnormalities that inhibit the resorption of cerebrospinal fluid, most often at the level of the arachnoid villi (Fig. 25-23).

Communicating hydrocephalus is due to abnormalities that inhibit the resorption of cerebrospinal fluid, most often at the level of the arachnoid villi (Fig. 25-23).

Figure 25-23 Communicating hydrocephalus.

Communicating hydrocephalus is due to abnormalities that inhibit the resorption of cerebrospinal fluid, most often at the level of the arachnoid villi. A, Classically, the 4th ventricle is dilated in communicating hydrocephalus (4) but normal in size in noncommunicating hydrocephalus. The temporal horns (T) are particularly sensitive to increases in intraventricular volume or pressure and are dilated in this patient. B, The frontal horns (F), occipital horns (O), and 3rd ventricle (3) are markedly dilated. There is a disproportionate dilatation of the ventricles compared to the sulci (which are normal to small in this case). Communicating hydrocephalus is usually treated with a ventricular shunt.

![]() Classically, the 4th ventricle is dilated in communicating hydrocephalus and normal in size in noncommunicating hydrocephalus.

Classically, the 4th ventricle is dilated in communicating hydrocephalus and normal in size in noncommunicating hydrocephalus.

Noncommunicating hydrocephalus occurs as a result of tumors, cysts, or other physically obstructing lesions that do not allow cerebrospinal fluid to exit from the ventricles.

Noncommunicating hydrocephalus occurs as a result of tumors, cysts, or other physically obstructing lesions that do not allow cerebrospinal fluid to exit from the ventricles.

Nonobstructive hydrocephalus from overproduction of CSF is rare and can occur with a choroid plexus papilloma.

Nonobstructive hydrocephalus from overproduction of CSF is rare and can occur with a choroid plexus papilloma.

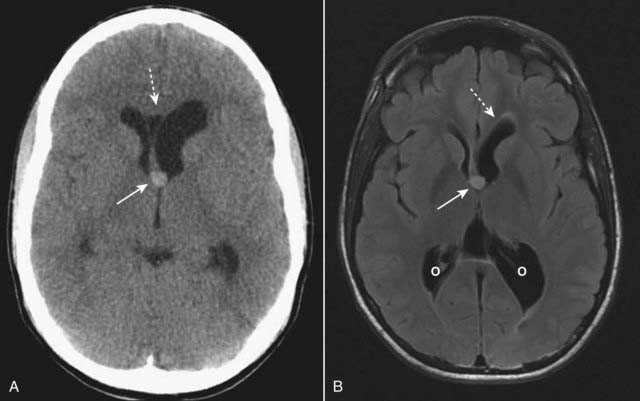

Figure 25-24 Colloid cyst of the 3rd ventricle, CT and MRI.

A colloid cyst is a rare, benign lesion of the 3rd ventricle that can cause obstructive hydrocephalus. A, There is a hyperdense mass in the anterior aspect of the 3rd ventricle (solid white arrow) causing asymmetric obstruction of the left foramen of Monro compared to the right (dotted white arrow). B, On this T2-like sequence, the lesion has increased signal (solid white arrow) and is causing dilatation of the frontal (dotted white arrow) and occipital (O) horns of the lateral ventricle.

Normal-Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH)

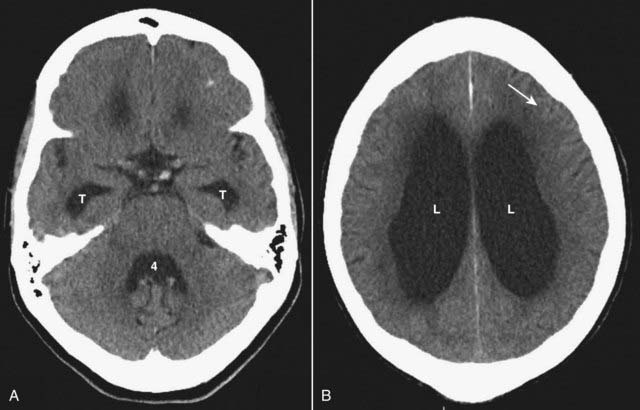

NPH is a form of communicating hydrocephalus characterized by a classical triad of clinical symptoms: abnormalities of gait, dementia, and urinary incontinence. The age of onset is typically between 50 and 70 years old.

NPH is a form of communicating hydrocephalus characterized by a classical triad of clinical symptoms: abnormalities of gait, dementia, and urinary incontinence. The age of onset is typically between 50 and 70 years old.

![]() Its recognition is important because it is usually amenable to treatment using a one-way ventriculoperitoneal shunt which allows the CSF to exit the ventricles and drain into the peritoneal cavity where the CSF is reabsorbed.

Its recognition is important because it is usually amenable to treatment using a one-way ventriculoperitoneal shunt which allows the CSF to exit the ventricles and drain into the peritoneal cavity where the CSF is reabsorbed.

Imaging findings are similar to other forms of communicating hydrocephalus and include enlarged ventricles, particularly the temporal horns, with normal or flattened sulci (Fig. 25-25).

Imaging findings are similar to other forms of communicating hydrocephalus and include enlarged ventricles, particularly the temporal horns, with normal or flattened sulci (Fig. 25-25).

Figure 25-25 Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH).

NPH is a form of communicating hydrocephalus characterized by a classical triad of clinical symptoms: abnormalities of gait, dementia, and urinary incontinence. A, The ventricles are enlarged, particularly the temporal horns (T) as well as the 4th ventricle (4). B, The bodies of the lateral ventricles (L) are also markedly enlarged but the sulci are normal or flattened (solid white arrow).

Cerebral Atrophy

Disorders associated with gross cerebral atrophy are also associated with dementia, Alzheimer disease being one of the most common. Atrophy implies a loss of both gray and white matter.

Disorders associated with gross cerebral atrophy are also associated with dementia, Alzheimer disease being one of the most common. Atrophy implies a loss of both gray and white matter.

![]() As in hydrocephalus, the ventricles dilate in cerebral atrophy but do so because a loss of normal cerebral tissue produces a vacant space that is filled passively with CSF. Unlike hydrocephalus, the dynamics of CSF production and absorption are normal in atrophy.

As in hydrocephalus, the ventricles dilate in cerebral atrophy but do so because a loss of normal cerebral tissue produces a vacant space that is filled passively with CSF. Unlike hydrocephalus, the dynamics of CSF production and absorption are normal in atrophy.

In general, cerebral atrophy leads to proportionate enlargement of both the ventricles and the sulci (Fig. 25-26).

In general, cerebral atrophy leads to proportionate enlargement of both the ventricles and the sulci (Fig. 25-26).

Figure 25-26 Diffuse cortical atrophy.

In general, cerebral atrophy produces enlargement of the sulci and the ventricles secondarily. CSF dynamics are normal in atrophy, compared to hydrocephalus. Disorders that cause gross cerebral atrophy are also associated with dementia, Alzheimer disease being one of the most common. A, The lateral ventricles (dotted white arrow) are enlarged. B, Unlike hydrocephalus, the sulci are also enlarged (solid white arrows).

Brain Tumors

Gliomas of the Brain

Gliomas are the most common primary, supratentorial, intraaxial mass in an adult. They account for 35% to 45% of all intracranial tumors. Glioblastoma multiforme accounts for more than half of all gliomas, astrocytomas about 20%, with the remainder split between ependymoma, medulloblastoma, and oligodendroglioma.

Gliomas are the most common primary, supratentorial, intraaxial mass in an adult. They account for 35% to 45% of all intracranial tumors. Glioblastoma multiforme accounts for more than half of all gliomas, astrocytomas about 20%, with the remainder split between ependymoma, medulloblastoma, and oligodendroglioma. Glioblastoma multiforme occurs more commonly in males between 65 and 75 years of age, especially in the frontal and temporal lobes. It has the worst prognosis of all gliomas.

Glioblastoma multiforme occurs more commonly in males between 65 and 75 years of age, especially in the frontal and temporal lobes. It has the worst prognosis of all gliomas. It infiltrates adjacent areas of the brain along white matter tracts making it difficult to resect, but, like most brain tumors, it does not produce extracerebral metastases.

It infiltrates adjacent areas of the brain along white matter tracts making it difficult to resect, but, like most brain tumors, it does not produce extracerebral metastases.

As the most aggressive of tumors, glioblastoma multiforme frequently demonstrates necrosis within the tumor.

As the most aggressive of tumors, glioblastoma multiforme frequently demonstrates necrosis within the tumor. The tumor infiltrates the surrounding brain tissue, frequently crossing the white matter tracts of the corpus callosum to the opposite cerebral hemisphere producing a pattern called a butterfly glioma.

The tumor infiltrates the surrounding brain tissue, frequently crossing the white matter tracts of the corpus callosum to the opposite cerebral hemisphere producing a pattern called a butterfly glioma. It tends to produce considerable vasogenic edema and mass effect and enhances with contrast, at least in part (Fig. 25-27).

It tends to produce considerable vasogenic edema and mass effect and enhances with contrast, at least in part (Fig. 25-27).

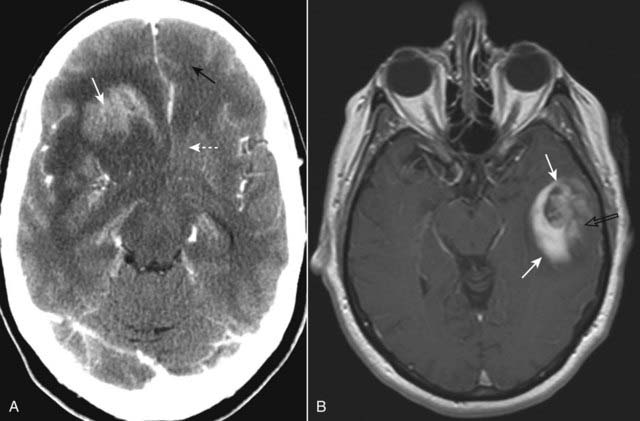

Figure 25-27 Glioblastoma multiforme, CT and MRI, two different patients.

A, In this contrast-enhanced CT, the tumor enhances (solid white arrow), produces considerable vasogenic edema (dotted white arrow), and infiltrates the surrounding brain tissue. There is either edema or tumor that has crossed over to the left frontal lobe (solid black arrow). B, Axial T1-weighted postgadolinium image in another patient demonstrates an enhancing mass in the left temporal lobe (solid white arrows). The internal enhancement of the mass is somewhat heterogeneous (open black arrow), which implies intratumoral necrosis or cystic change.

Metastases

Solitary intraaxial masses are about evenly split between solitary metastases and primary brain tumors. About 40% of all intracranial neoplasms are metastases. Lung, breast, and melanoma are the most common primary malignancies to produce brain metastases.

Solitary intraaxial masses are about evenly split between solitary metastases and primary brain tumors. About 40% of all intracranial neoplasms are metastases. Lung, breast, and melanoma are the most common primary malignancies to produce brain metastases.

Figure 25-28 Metastases, contrast-enhanced CT.

About 40% of all intracranial neoplasms are metastases. They typically produce well-defined, round masses near the gray-white junction and are usually multiple. With intravenous contrast, they can enhance, sometimes demonstrating ring enhancement (solid white arrows). Lung, breast, and melanoma are the most common primary malignancies to produce brain metastases. This patient had lung cancer.

Meningioma

Meningiomas are the most common extraaxial mass, usually occurring in middle-aged women. Their most common locations are parasaggital, over the convexities, the sphenoid wing, and the cerebellopontine angle cistern, in decreasing frequency.

Meningiomas are the most common extraaxial mass, usually occurring in middle-aged women. Their most common locations are parasaggital, over the convexities, the sphenoid wing, and the cerebellopontine angle cistern, in decreasing frequency. On unenhanced CT, over half are hyperdense to normal brain and about 20% contain calcification (Fig. 25-29).

On unenhanced CT, over half are hyperdense to normal brain and about 20% contain calcification (Fig. 25-29).

Figure 25-29 Meningioma, nonenhanced CT.

Meningiomas usually occur in middle-aged women and are the most common extraaxial mass. This meningioma is arising from the right sphenoid wing, a relatively common site of origin. On unenhanced CT, over half are hyperdense to normal brain and about 20% contain calcification, as does this lesion that appears as a dense mass (solid white arrow). On contrast-enhanced studies, meningiomas markedly enhance.

Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic Neuroma)

Vestibular schwannomas are the most common schwannomas of all of the cranial nerves. Their most common symptom is hearing loss, but they also produce tinnitus and disturbances in equilibrium.

Vestibular schwannomas are the most common schwannomas of all of the cranial nerves. Their most common symptom is hearing loss, but they also produce tinnitus and disturbances in equilibrium. They occur most commonly along the course of the 8th nerve within the internal auditory canal at the cerebellopontine angle (Fig. 25-30).

They occur most commonly along the course of the 8th nerve within the internal auditory canal at the cerebellopontine angle (Fig. 25-30). Like meningiomas, they can be multiple (i.e., bilateral) and associated with neurofibromatosis type 2.

Like meningiomas, they can be multiple (i.e., bilateral) and associated with neurofibromatosis type 2.

Figure 25-30 Vestibular schwannoma, T1-weighted MRI with contrast.

There is a homogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass at the right cerebellopontine angle (solid white arrow), classical for a vestibular schwannoma. These tumors occur most commonly along the course of the 8th nerve. Hearing loss is the most common presenting symptom.

![]() Contrast-enhanced MRI is the most sensitive imaging study for detecting vestibular schwannomas which virtually always enhance, usually homogeneously. On nonenhanced MR, they may be of the same density as the adjacent pontine tissue and difficult to detect.

Contrast-enhanced MRI is the most sensitive imaging study for detecting vestibular schwannomas which virtually always enhance, usually homogeneously. On nonenhanced MR, they may be of the same density as the adjacent pontine tissue and difficult to detect.

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is considered to be autoimmune in origin and is the most common demyelinating disease. Any neurologic function can be affected by the disease, with some patients having mostly cognitive changes, while others present with ataxia, paresis, or visual symptoms.

Multiple sclerosis is considered to be autoimmune in origin and is the most common demyelinating disease. Any neurologic function can be affected by the disease, with some patients having mostly cognitive changes, while others present with ataxia, paresis, or visual symptoms. MS is characterized by a relapsing and remitting course. There are specific clinical criteria that must be met for establishing this diagnosis, but imaging by MRI along with ancillary tests now permit the diagnosis to be made after a single episode.

MS is characterized by a relapsing and remitting course. There are specific clinical criteria that must be met for establishing this diagnosis, but imaging by MRI along with ancillary tests now permit the diagnosis to be made after a single episode. It characteristically affects myelinated (white matter) tracks with lesions known as plaques. Lesions of multiple sclerosis have a predilection for the periventricular area, corpus callosum, and optic nerves.

It characteristically affects myelinated (white matter) tracks with lesions known as plaques. Lesions of multiple sclerosis have a predilection for the periventricular area, corpus callosum, and optic nerves.

![]() MRI is the study of choice in imaging multiple sclerosis because of its greater sensitivity than CT in demonstrating plaques both in the brain and spinal cord.

MRI is the study of choice in imaging multiple sclerosis because of its greater sensitivity than CT in demonstrating plaques both in the brain and spinal cord.

On T1-weighted, nonenhanced images, they are isointense to hypointense, but in acute MS, the lesions enhance with gadolinium on T1-weighted images.

On T1-weighted, nonenhanced images, they are isointense to hypointense, but in acute MS, the lesions enhance with gadolinium on T1-weighted images. The lesions tend to be oriented with their long axes perpendicular to the ventricular walls (Fig. 25-31).

The lesions tend to be oriented with their long axes perpendicular to the ventricular walls (Fig. 25-31).

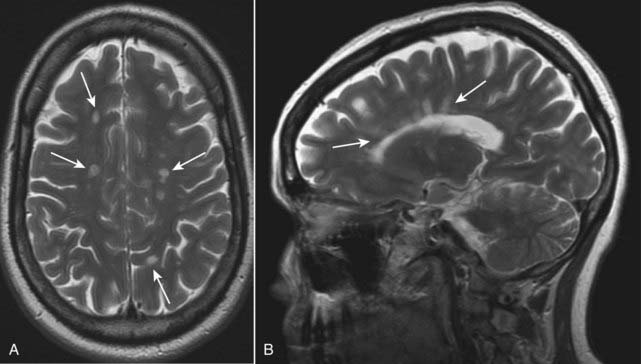

Figure 25-31 Multiple sclerosis, axial and sagittal MRI.

Lesions of multiple sclerosis have a predilection for the periventricular area, corpus callosum, and optic nerves (solid white arrows). A, The lesions produce discrete, globular foci of high-signal intensity (white) on T2-weighted images. B, Ovoid lesions with their long axis perpendicular to the ventricular surface seen in multiple sclerosis are called Dawson fingers (solid white arrows). MRI is the study of choice in imaging multiple sclerosis because of its greater sensitivity than CT in demonstrating plaques both in the brain and spinal cord.

Terminology

| Term | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Intraaxial/extraaxial | Intraaxial lesions originate in the brain parenchyma; extraaxial lesions originate outside of the brain substance (i.e., meninges, intraventricular) |

| Infratentorial | Beneath the tentorium cerebelli that includes the cerebellum, brain stem, 4th ventricle, and cerebellopontine angles |

| Supratentorial | Above the tentorium cerebelli which includes the cerebral hemispheres (frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes) and the sella |

| Transient ischemic attack (TIA) | Sudden neurologic loss that persists for a short time and resolves within 24 hours |

| Completed stroke | Neurologic deficit lasts for >21 days |

| Open versus closed head injuries | Open: communication of intracranial material outside of the skull Closed: no external communication |

| Increased attenuation/hyperattenuation/ hyperdense/hyperintense | Terms that might be used to describe any tissue brighter than its surrounding tissues |

| Decreased attenuation/hypoattenuation/ hypodense/hypointense | Terms that might be used to describe any tissue darker than its surrounding tissues |

| Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) | An MRI sequence that can be rapidly acquired and which is extremely sensitive to detecting abnormalities in normal water movement in the brain so that it can identify a stroke within minutes after the event. DWI also helps differentiate acute infarction from more chronic infarction |

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Some Common Causes of Intracranial Pathology on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Some Common Causes of Intracranial Pathology

The normal anatomy of the brain is more easily recognized on CT scans, although MRI is generally the study of choice for detecting and staging intracranial and spinal cord abnormalities because of its superior contrast and soft tissue resolution.

Unenhanced CT is usually the study of first choice in acute head trauma. The search for findings should initially focus on finding mass effect or blood.

Linear skull fractures are important mainly for the intracranial abnormalities that may have occurred at the time of the fracture; depressed skull fractures can be associated with underlying brain injury and may require elevation of the fragment; basilar skull fractures are more serious and can be associated with CSF leaks.

Blow-out fractures of the orbit result from a direct blow and may present with orbital emphysema, fracture through either the floor or medial wall of the orbit, and entrapment of fat and extraocular muscles in the fracture.

There are four types of intracranial hemorrhages that may be associated with trauma: epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Epidural hematomas represent hemorrhage into the potential space between the dura mater and the inner table of the skull and are usually due to injuries to the middle meningeal artery or vein from blunt head trauma; almost all (95%) have an associated skull fracture. When acute, epidural hematomas appear as hyperintense collections of blood that typically have a lenticular shape; as they age, they become hypodense to normal brain.

Subdural hematomas most commonly result from deceleration injuries or falls; they represent hemorrhage into the potential space between the dura mater and the arachnoid; acute subdural hematomas portend the presence of more severe brain injury. Subdural hematomas are crescent-shaped bands of blood that may cross suture lines and enter the interhemispheric fissure although they do not cross the midline; they are typically concave inward to the brain and may appear isointense (isodense) to the remainder of the brain as they become subacute and hypodense when chronic.

Traumatic intracerebral hematomas are frequently from shearing injuries and present as petechial or larger hemorrhages in the frontal or temporal lobes; they may be associated with increased intracranial pressure and brain herniation.

Brain herniations include subfalcine, transtentorial, foramen magnum/tonsillar, sphenoid, and extracranial herniations.

Diffuse axonal injury is a serious consequence of trauma in which the corpus callosum is most commonly affected; CT findings are similar to those for intracerebral hemorrhage following head trauma; MRI is the study of choice in identifying diffuse axonal injury.

In general, increased intracranial pressure is due to either increased volume of the brain (cerebral edema) or increased size of the ventricles (hydrocephalus).

There are two major categories of cerebral edema: vasogenic and cytotoxic.

Vasogenic edema represents extracellular accumulation of fluid and is the type that occurs with malignancy and infection and affects the white matter more.

Cytotoxic edema represents cellular edema, is due to cell death, and affects both the gray and white matter; cytotoxic edema is associated with cerebral ischemia.

Stroke denotes an acute loss of neurologic function that occurs when the blood supply to an area of the brain is lost or compromised. MRI is more sensitive to the early diagnosis of stroke than CT. There are certain patterns of ischemia that develop depending on which vascular territory is involved.

Strokes are usually due to embolic (more common) or thrombotic events and are typically divided into ischemic (more common) and hemorrhagic varieties (poorer prognosis); hypertension is frequently associated.

Intracerebral hemorrhage will display increased density on nonenhanced CT scans of the brain; as the clot begins to form, the blood becomes denser for about 3 days because of dehydration of the clot and then decreases in density, becoming invisible over the next several weeks; after about 2 months, only a small hypodensity may remain.

Berry aneurysms are usually formed from congenital weakening in the arterial wall; when they rupture, the blood typically enters the subarachnoid space presenting in the basilar cisterns and in the sulci. The aneurysm itself can be detected on either CTA or MRA.

Hydrocephalus represents an increased volume of CSF in the ventricular system and may be due to overproduction of cerebrospinal fluid (rare), underabsorption of cerebrospinal fluid at the level of the arachnoid villi (communicating), or obstruction of the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid from the ventricles (noncommunicating).

Normal-pressure hydrocephalus is a form of communicating hydrocephalus characterized by a classical triad of abnormalities of gait, dementia, and urinary incontinence that may be improved by insertion of a ventricular shunt.

Cerebral atrophy is a loss of both gray and white matter that may resemble hydrocephalus except that the CSF fluid dynamics are normal in atrophy and, in general, cerebral atrophy produces proportionate enlargement of both the ventricles and the sulci; there is diffuse cerebral atrophy associated with Alzheimer disease.

Glioblastoma multiforme is a highly malignant glioma that occurs most commonly in the frontal and temporal lobes producing a very aggressive, infiltrating, partially enhancing, sometimes necrotic mass that may cross the corpus callosum to the opposite cerebral hemisphere.

Metastases to the brain are frequently well-defined, round masses near the gray-white junction, usually multiple, typically hypodense or isodense on nonenhanced CT that enhance with contrast; they can provoke vasogenic edema out of proportion to the size of the mass; lung, breast, and melanoma are the most frequent sources of brain metastases.

Meningiomas usually occur in middle-aged women in a parasaggital location; they tend to be slow-growing with an excellent prognosis if surgically excised; on CT, they characteristically can be dense without contrast because of calcification within the tumor and may enhance dramatically.

Vestibular schwannomas occur most commonly along the course of the 8th cranial nerve within the internal auditory canal at the cerebellopontine angle and are best identified on MRI, where they homogeneously enhance.

Multiple sclerosis is the most common demyelinating disease, characterized by a relapsing and remitting course and a predilection for the periventricular area, corpus callosum, and optic nerves; it is best visualized on MRI and produces discrete, globular foci of high-signal intensity (white) on T2-weighted images.