Nuclear Medicine

Understanding the Principles and Recognizing the Basics

How It Works

A radioactive isotope (radioisotope) is an unstable form of an element that emits radiation from its nucleus as it decays. Eventually, the end product is a stable, nonradioactive isotope of another element.

A radioactive isotope (radioisotope) is an unstable form of an element that emits radiation from its nucleus as it decays. Eventually, the end product is a stable, nonradioactive isotope of another element. Radioisotopes can be produced artificially (most frequently by neutron enrichment in a nuclear reactor or in a cyclotron) or may occur naturally. Naturally occurring radioisotopes include uranium and thorium. The vast majority of radioisotopes are produced artificially.

Radioisotopes can be produced artificially (most frequently by neutron enrichment in a nuclear reactor or in a cyclotron) or may occur naturally. Naturally occurring radioisotopes include uranium and thorium. The vast majority of radioisotopes are produced artificially. Radiopharmaceuticals are combinations of radioisotopes attached (for the purposes of this chapter) to a pharmaceutical with binding properties that allow it to concentrate in certain body tissues, e.g., the lungs, thyroid, or bones. Radioisotopes used in clinical nuclear medicine are also referred to as radionuclides, radiotracers, or sometimes simply tracers.

Radiopharmaceuticals are combinations of radioisotopes attached (for the purposes of this chapter) to a pharmaceutical with binding properties that allow it to concentrate in certain body tissues, e.g., the lungs, thyroid, or bones. Radioisotopes used in clinical nuclear medicine are also referred to as radionuclides, radiotracers, or sometimes simply tracers. Various body organs have a specific affinity for, or absorption of, different biologically active chemicals. For example, the thyroid takes up iodine, the brain utilizes glucose, bones utilize phosphates, and particles of a certain size can be trapped in the lung capillaries.

Various body organs have a specific affinity for, or absorption of, different biologically active chemicals. For example, the thyroid takes up iodine, the brain utilizes glucose, bones utilize phosphates, and particles of a certain size can be trapped in the lung capillaries. After the radiopharmaceutical is carried to a tissue or organ in the body, its radioactive emissions allow it to be measured and imaged using a detection device called a gamma camera.

After the radiopharmaceutical is carried to a tissue or organ in the body, its radioactive emissions allow it to be measured and imaged using a detection device called a gamma camera.TABLE 1 RADIOPHARMACEUTICALS USED IN NUCLEAR MEDICINE

| Organ | Radioactive Isotope | Pharmaceutical |

|---|---|---|

| Brain | Technetium 99m (Tc 99m), Iodine 123 | Pertechnetate, glucoheptonate, diethylenetriaminepenta-acetic acid (DTPA) |

| Cardiac | Thallium 201, Tc 99m | Pyrophosphate, pertechnetate, sestamibi, teboroxime, labeled red blood cells |

| Lung | Xenon-127, Xenon-133, Krypton-81m, Tc 99m aerosolized | Macroaggregated albumin |

| Bone | Tc 99m | Phosphates, diphosphonates (e.g., MDP) |

| Kidney | Tc 99m, Iodine 131, Iodine 123 | Glucoheptonate, mercaptoacetyltriglycine, Hippuran, DTPA |

| Thyroid | Iodine 131, Iodine 123, Iodine 125, Tc 99m | Pertechnetate with Tc 99m |

| Multiple organs | Gallium 67 | Citrate |

| White blood cells (infection) | Indium 111, Tc 99m | White blood cells |

Radioactive Decay

Unstable isotopes attempt to reach stability by one or more of several processes. They may undergo splitting (fission), or they may emit particles (alpha or beta particles) and/or energy (gamma rays) in the form of radiation.

Unstable isotopes attempt to reach stability by one or more of several processes. They may undergo splitting (fission), or they may emit particles (alpha or beta particles) and/or energy (gamma rays) in the form of radiation.

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Physical half-life | The time required for the number of radioactive atoms in a sample to decrease by 50% |

| Biologic half-life | The time needed for half of a radiopharmaceutical to disappear from the biologic system into which it has been introduced |

| Effective half-life | Time dependent on both the physical half-life and the biological clearance |

| Isotopes | Species of atoms of a chemical element with the same atomic number (protons in nucleus) but with different numbers of neutrons and thus atomic masses (total number of protons and neutrons); every element has at least one isotope |

| Stable isotopes | Do not undergo radioactive decay |

| Unstable isotopes | Undergo spontaneous disintegration |

| Atomic number (Z) | Defines an element; all atoms with the same atomic number have nearly the same properties |

| Mass number (A) | The number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus; different numbers of neutrons is what produces isotopes |

Half-Life

In order for a radioisotope to be useful for medical diagnosis, it must be capable of emitting gamma rays of sufficient energy to be measurable outside of the body. It also must have a half-life that is long enough for it to still be radioactive after shipping and preparation, but sufficiently short so as to decay soon after it is used for imaging.

In order for a radioisotope to be useful for medical diagnosis, it must be capable of emitting gamma rays of sufficient energy to be measurable outside of the body. It also must have a half-life that is long enough for it to still be radioactive after shipping and preparation, but sufficiently short so as to decay soon after it is used for imaging. The physical half-life of a radioisotope is the time required for the number of radioactive atoms in a sample to decrease by 50%. Physical half-life is a property inherent to the radioisotope. Most radioisotopes for medical use must have half-lives of hours or days.

The physical half-life of a radioisotope is the time required for the number of radioactive atoms in a sample to decrease by 50%. Physical half-life is a property inherent to the radioisotope. Most radioisotopes for medical use must have half-lives of hours or days. Table 3 outlines the physical half-lives of some of the most commonly used radioisotopes.

Table 3 outlines the physical half-lives of some of the most commonly used radioisotopes.

TABLE 3 PHYSICAL HALF-LIVES OF COMMONLY USED RADIOISOTOPES

| Radioisotope | Physical Half-Life |

|---|---|

| Technetium 99m | 6 hours |

| Iodine 131 | 8 days |

| Iodine 123 | 13.2 hours |

| Gallium 67 | 3.3 days |

| Indium 111 | 2.8 days |

| Thallium 201 | 73 hours |

Biological half-life accounts for the biological clearance of a radiopharmaceutical from an organ or tissue. If a radiopharmaceutical is cleared from the body via the kidneys, but kidney function is impaired, the radiopharmaceutical will have a longer biological half-life than if kidney function was normal.

Biological half-life accounts for the biological clearance of a radiopharmaceutical from an organ or tissue. If a radiopharmaceutical is cleared from the body via the kidneys, but kidney function is impaired, the radiopharmaceutical will have a longer biological half-life than if kidney function was normal.Nuclear Medicine Equipment

By far, the most widely used radioisotope is technetium 99m (abbreviated Tc 99m, the “m” standing for metastable). It has a half-life of 6 hours, meaning that it loses roughly half of its radioactivity in that time. It decays by emitting low-energy gamma rays rather than higher energy beta emission and is easily combined with a wide variety of biologically active substances.

By far, the most widely used radioisotope is technetium 99m (abbreviated Tc 99m, the “m” standing for metastable). It has a half-life of 6 hours, meaning that it loses roughly half of its radioactivity in that time. It decays by emitting low-energy gamma rays rather than higher energy beta emission and is easily combined with a wide variety of biologically active substances.Detecting and Measuring the Radioactivity of an Isotope

Scintillation detectors

Scintillation detectors

Images can be acquired either as static, whole body or dynamic images (change in activity in the same location over a period of time), or SPECT images.

Images can be acquired either as static, whole body or dynamic images (change in activity in the same location over a period of time), or SPECT images. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging is a nuclear medicine study performed by using a gamma camera to acquire multiple two-dimensional (2D) images from multiple angles, which are then reconstructed by computer into a three-dimensional (3D) dataset that can be manipulated to demonstrate thin slices in any projection. To acquire SPECT scans, the gamma camera rotates around the patient.

Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging is a nuclear medicine study performed by using a gamma camera to acquire multiple two-dimensional (2D) images from multiple angles, which are then reconstructed by computer into a three-dimensional (3D) dataset that can be manipulated to demonstrate thin slices in any projection. To acquire SPECT scans, the gamma camera rotates around the patient.Nuclear Medicine Safety

Each dose has to be assayed for its radioactivity before being administered to the patient. Dose calibration is essential in assuring that a safe and effective amount of radiopharmaceutical is given. This is usually done by inserting a syringe containing the radiopharmaceutical into an ionization chamber that converts the ionization of a sample into a measurable dose, depending on the radioisotope used.

Each dose has to be assayed for its radioactivity before being administered to the patient. Dose calibration is essential in assuring that a safe and effective amount of radiopharmaceutical is given. This is usually done by inserting a syringe containing the radiopharmaceutical into an ionization chamber that converts the ionization of a sample into a measurable dose, depending on the radioisotope used. The performance of the dose calibrator itself must be evaluated at set intervals utilizing a series of tests to ensure that the calibrator is accurate and reliable.

The performance of the dose calibrator itself must be evaluated at set intervals utilizing a series of tests to ensure that the calibrator is accurate and reliable. A locked and controlled area is needed for the storage and preparation of radiopharmaceuticals. Techniques need to be in place to assure the material being injected is sterile and free of pyrogens.

A locked and controlled area is needed for the storage and preparation of radiopharmaceuticals. Techniques need to be in place to assure the material being injected is sterile and free of pyrogens. Spills of liquid radiopharmaceuticals sometimes occur accidentally; there are prescribed methods for containing and cleaning the spill as well as disposing of the material used for the cleanup. The area in which the spill has occurred may be monitored by using Geiger counters.

Spills of liquid radiopharmaceuticals sometimes occur accidentally; there are prescribed methods for containing and cleaning the spill as well as disposing of the material used for the cleanup. The area in which the spill has occurred may be monitored by using Geiger counters. While there is no absolute contraindication to the use of radiopharmaceuticals during pregnancy, some radioisotopes, e.g., radioactive iodine, can cross the placenta and be concentrated in the fetal thyroid. Similarly, women who are breastfeeding may have to suspend breastfeeding for a period of time following administration of some radiopharmaceuticals because the pharmaceutical may pass through breast milk to the child. Renal excretion of some radioisotopes means they collect and concentrate in the urinary bladder of the mother and can pose a potential risk by their proximity to the developing fetus.

While there is no absolute contraindication to the use of radiopharmaceuticals during pregnancy, some radioisotopes, e.g., radioactive iodine, can cross the placenta and be concentrated in the fetal thyroid. Similarly, women who are breastfeeding may have to suspend breastfeeding for a period of time following administration of some radiopharmaceuticals because the pharmaceutical may pass through breast milk to the child. Renal excretion of some radioisotopes means they collect and concentrate in the urinary bladder of the mother and can pose a potential risk by their proximity to the developing fetus. Adverse reactions to the radiopharmaceutical itself are extremely rare and are related to the pharmaceutical, such as those composed of human serum albumin, rather than the radioisotope.

Adverse reactions to the radiopharmaceutical itself are extremely rare and are related to the pharmaceutical, such as those composed of human serum albumin, rather than the radioisotope. Some types of radiotherapy utilizing radiopharmaceuticals administered at much higher doses than for diagnostic studies may require the patient to be hospitalized in order to assure radiation safety. Patients may be assigned to private rooms without outside visitors for 24 hours. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission no longer requires hospitalization for Iodine 131 treatment of the thyroid.

Some types of radiotherapy utilizing radiopharmaceuticals administered at much higher doses than for diagnostic studies may require the patient to be hospitalized in order to assure radiation safety. Patients may be assigned to private rooms without outside visitors for 24 hours. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission no longer requires hospitalization for Iodine 131 treatment of the thyroid.Commonly Used Nuclear Medicine Studies

Bone Scans

Bone scans are the screening method of choice for the detection of osseous metastatic disease and for diagnosing fractures before they become visible by conventional radiography.

Bone scans are the screening method of choice for the detection of osseous metastatic disease and for diagnosing fractures before they become visible by conventional radiography. Bone scans offer the advantages of being widely available and inexpensive, and they can image the entire skeleton at the same time. While MRI scans may be more sensitive in detecting osseous metastases, they are less widely available and usually much more expensive. The disadvantages of bone scanning are poor spatial and contrast resolution.

Bone scans offer the advantages of being widely available and inexpensive, and they can image the entire skeleton at the same time. While MRI scans may be more sensitive in detecting osseous metastases, they are less widely available and usually much more expensive. The disadvantages of bone scanning are poor spatial and contrast resolution. Technetium 99m (Tc 99m) methylene diphosphonate (MDP) is the radiopharmaceutical most frequently used for bone scanning. It combines a radioisotope, technetium 99m, with a pharmaceutical (MDP) that directs the isotope to bone. Diphosphonates are rapidly removed from the circulation and produce little background noise from uptake in soft tissues.

Technetium 99m (Tc 99m) methylene diphosphonate (MDP) is the radiopharmaceutical most frequently used for bone scanning. It combines a radioisotope, technetium 99m, with a pharmaceutical (MDP) that directs the isotope to bone. Diphosphonates are rapidly removed from the circulation and produce little background noise from uptake in soft tissues. After the intravenous injection of the radiopharmaceutical, most of the dose is quickly extracted by the bone. The remaining radiopharmaceutical is excreted by the kidneys and subsequently collects in the urinary bladder. Less than 5% of the injected dose remains in the blood 3 hours after injection.

After the intravenous injection of the radiopharmaceutical, most of the dose is quickly extracted by the bone. The remaining radiopharmaceutical is excreted by the kidneys and subsequently collects in the urinary bladder. Less than 5% of the injected dose remains in the blood 3 hours after injection. In most instances, the entire body is imaged about 2 to 4 hours after injection, either by producing one image of the whole body, multiple spot images of particular body parts, or both. Anterior and posterior views are frequently obtained because each view brings different structures closer to the gamma camera for optimum imaging, e.g., the sternum on the anterior view and the spine on the posterior view.

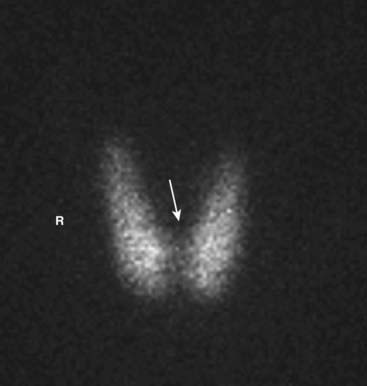

In most instances, the entire body is imaged about 2 to 4 hours after injection, either by producing one image of the whole body, multiple spot images of particular body parts, or both. Anterior and posterior views are frequently obtained because each view brings different structures closer to the gamma camera for optimum imaging, e.g., the sternum on the anterior view and the spine on the posterior view. Unlike the convention used for viewing other studies in radiology, the patient’s right side is not always on your left in nuclear scans. This can be confusing, so make sure you look for the labels on the scan (Fig. 1).

Unlike the convention used for viewing other studies in radiology, the patient’s right side is not always on your left in nuclear scans. This can be confusing, so make sure you look for the labels on the scan (Fig. 1).

Anterior and posterior views are frequently obtained, since each view brings different structures closer to the gamma camera for optimum imaging, e.g., the sternum on the anterior view (solid white arrow) and the spine on the posterior view (dotted white arrow). Notice that the kidneys are normally visible on the posterior view (white oval). Unlike the convention used in viewing other studies in radiology, the patient’s right side is not always on your left. On posterior views, the patient’s right side is on your right. This can be confusing, so make sure you look for the labels on the scan. In many cases a white marker dot will be located on the patient’s right side (white circles).

Metastases to bone

Metastases to bone

Metastatic bone disease usually presents with a pattern of multiple, asymmetric focal areas of increased uptake (hot spots) on bone scans (white arrows). Even lytic metastases, e.g., those caused by bronchogenic carcinoma, usually produce enough osteoblastic response to be positive on a bone scan. This patient had metastatic breast carcinoma and had diffuse skeletal metastases including the ribs, pelvis, and spine.

Figure 3 Multiple myeloma on conventional radiography.

Bone scans will frequently be negative in multiple myeloma because of the almost purely lytic nature of the lesions (solid black arrow) unless there is an associated pathologic fracture. Conventional radiographs of the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton (most often called a bone or metastatic survey) may be more diagnostic in this disease than a bone scan.

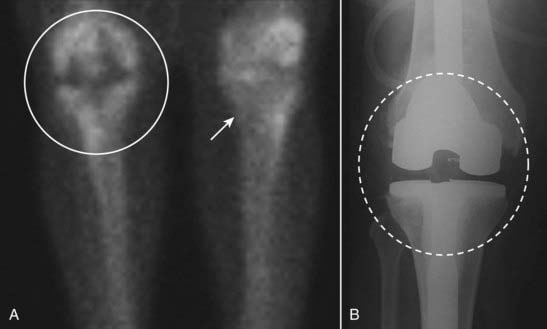

Figure 4 Photopenic abnormality.

Photopenic lesions (photon-deficient lesions, cold spots) are areas of abnormally diminished or absent radiotracer uptake on the bone scan. They can be produced by lesions such as avascular necrosis or when a process is so destructive, no bone-forming elements remain (e.g., renal or thyroid metastases). They can also be produced by a prosthesis, which can obviously not extract the radiotracer as normal bone does. In this case, a photopenic area is seen in the right knee (white circle) compared to left knee (white arrow) (A), produced by a metallic knee replacement seen better on the conventional radiograph (dashed circle in B).

Superscans are produced when there is diffuse and relatively uniform uptake of radioisotope because of a high rate of bone turnover, especially in bones extensively involved by metastatic disease. At first glance, a skeleton completely infiltrated by tumor, such as in this scan, may mimic a normal bone scan. The clue to the abnormality is decreased or absent uptake in the kidneys (white oval) because so much of the radiopharmaceutical is extracted by the bone, very little reaches the kidneys in a superscan. This patient had metastatic prostate carcinoma, which is a common cause of a superscan. The radiotracer was injected into a right antecubital vein (solid white arrow) and tracer outlines urine excreted into the patient’s Foley catheter (dotted white arrow).

A, Stress fractures may be difficult or impossible to visualize on conventional radiographs done soon after the injury (white circle shows a normal metatarsal 2 days after pain began). B, Bone scans may be positive as early as 24 hours after a fracture and can be especially helpful in detecting occult stress fractures by demonstrating markedly increased uptake in the affected bone (white arrow points to metatarsal). C, Three weeks after the injury seen in A, extensive external callous formation is seen around the healing fracture (black circle).

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis

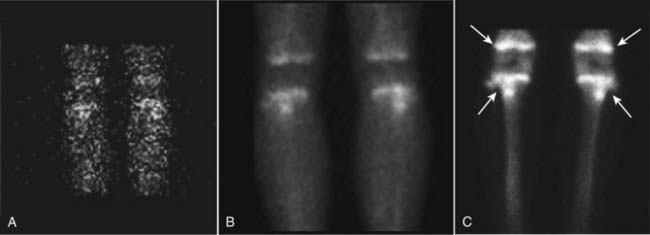

Figure 7 Normal triple phase bone scan, knees.

This is a 16-year-old patient, so the growth plates take up radiotracer normally (white arrows). Images are obtained within the first minute after injection (A, flow phase), about 5 minutes after injection (B, blood pool or tissue phase) and then 2 to 4 hours after injection (C, delayed or skeletal phase). Flow is normally equal bilaterally; the tracer then shows activity in the soft tissues and is quickly extracted by the bone, clearing from the soft tissues by the delayed images.

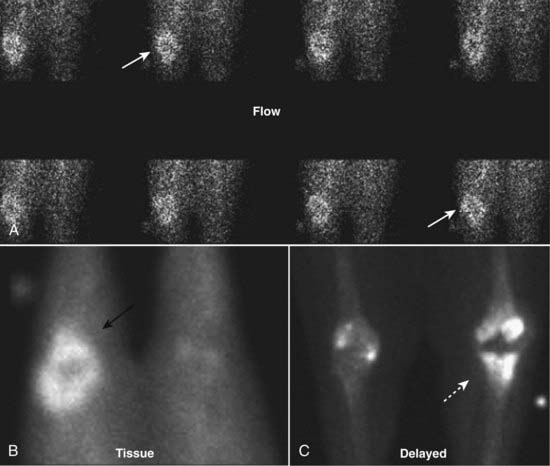

Figure 8 Triple phase bone scan, cellulitis.

A, There is increased flow to the left ankle shown on the flow phase (solid white arrows). B, Increased uptake is again seen on the blood pool phase in the soft tissues (dotted white arrows). C, On the delayed phase, the increased uptake is again seen in the soft tissues of the ankle, but is not localized to the bone itself (black arrows). Osteomyelitis would show progressive uptake in the bone and clearance from the soft tissues on the delayed phase.

Figure 9 Triple phase bone scan, osteomyelitis.

Increased radiotracer uptake is seen in sequential images of the flow phase (solid white arrows), tissue phase (solid black arrow), and localized to the bone of the knee in the delayed phase (dotted white arrow). This patient had a total knee prosthesis that had become infected.

Pulmonary Ventilation/Perfusion Scans for Pulmonary Embolism

Immobilization, usually following surgery, is the risk factor most often associated with pulmonary embolism. Other known risk factors include malignancy, thrombophlebitis, trauma to the lower extremities, and stroke.

Immobilization, usually following surgery, is the risk factor most often associated with pulmonary embolism. Other known risk factors include malignancy, thrombophlebitis, trauma to the lower extremities, and stroke. CT pulmonary angiography (CT-PA) has largely replaced nuclear medicine ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scans as the modality of choice in diagnosing pulmonary thromboembolism.

CT pulmonary angiography (CT-PA) has largely replaced nuclear medicine ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scans as the modality of choice in diagnosing pulmonary thromboembolism. Ventilation/perfusion scans are used primarily if CT-PA is not available or if the patient has a contraindication to the administration of intravenous iodinated contrast material, such as impaired renal function or severe allergy to contrast.

Ventilation/perfusion scans are used primarily if CT-PA is not available or if the patient has a contraindication to the administration of intravenous iodinated contrast material, such as impaired renal function or severe allergy to contrast. Chest radiographs should be obtained to aid in the interpretation of the V/Q scan and to rule out another cause of the patient’s symptoms besides pulmonary embolism. In most cases of pulmonary embolism, the initial chest radiograph is normal (Fig. 10).

Chest radiographs should be obtained to aid in the interpretation of the V/Q scan and to rule out another cause of the patient’s symptoms besides pulmonary embolism. In most cases of pulmonary embolism, the initial chest radiograph is normal (Fig. 10).

Figure 10 Chest radiograph in pulmonary embolism.

Chest radiographs should be obtained to rule out another cause of the patient’s symptoms besides pulmonary embolism and to aid in the interpretation of the nuclear scan. In most cases of pulmonary embolism, the initial chest radiograph is normal or demonstrates nonspecific findings such as the discoid atelectasis (subsegmental atelectasis) seen in this patient (black arrows).

If the chest radiograph is normal, then V/Q scanning may be diagnostic. If the chest radiograph is abnormal, a CT-PA is usually performed.

If the chest radiograph is normal, then V/Q scanning may be diagnostic. If the chest radiograph is abnormal, a CT-PA is usually performed. The pulmonary perfusion study is performed using technetium 99m macroaggregated albumin (MAA). The radioisotope is technetium 99m and the pharmaceutical to which it is bound is the macroaggregated albumin. The radiopharmaceutical is then injected intravenously.

The pulmonary perfusion study is performed using technetium 99m macroaggregated albumin (MAA). The radioisotope is technetium 99m and the pharmaceutical to which it is bound is the macroaggregated albumin. The radiopharmaceutical is then injected intravenously. Macroaggregated albumin is prepared by heating human serum albumin. It can be produced to a particle size that is extracted 80% or more during its passage through the pulmonary vasculature. Although an average of about 350,000 MAA particles are injected, only about 1 in a 1000 lung capillaries are occluded with a usual injection, so the patient experiences no symptoms from the injection.

Macroaggregated albumin is prepared by heating human serum albumin. It can be produced to a particle size that is extracted 80% or more during its passage through the pulmonary vasculature. Although an average of about 350,000 MAA particles are injected, only about 1 in a 1000 lung capillaries are occluded with a usual injection, so the patient experiences no symptoms from the injection. Images of the lungs are obtained in multiple positions (e.g., anterior, posterior, right and left lateral and oblique projections) as soon as the radiopharmaceutical is injected.

Images of the lungs are obtained in multiple positions (e.g., anterior, posterior, right and left lateral and oblique projections) as soon as the radiopharmaceutical is injected. The normal perfusion scan will show uniform uptake throughout the lungs with photopenic areas normally seen in the region of the hila and the heart, especially on the anterior projection (Fig. 11).

The normal perfusion scan will show uniform uptake throughout the lungs with photopenic areas normally seen in the region of the hila and the heart, especially on the anterior projection (Fig. 11).

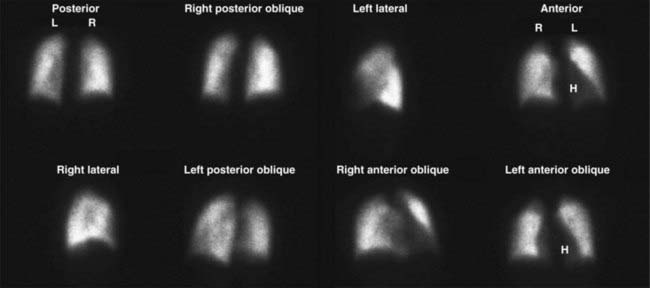

Figure 11 Normal lung perfusion scan.

The normal perfusion scan will show uniform uptake throughout the lungs with photopenic areas normally seen in the region of the hila and the heart (H), especially on the anterior projection. The lungs are imaged in multiple projections during a lung scan to better demonstrate small perfusion abnormalities.

If the perfusion study is abnormal, then the ventilation scan is performed with the patient breathing either radioactive xenon, krypton gas, or an aerosol labeled with technetium 99m.

If the perfusion study is abnormal, then the ventilation scan is performed with the patient breathing either radioactive xenon, krypton gas, or an aerosol labeled with technetium 99m. In a normal ventilation scan, the radiotracer washes into the lungs homogeneously, usually after the first deep breath. Most of the radiotracer will normally wash out of the lungs within two minutes (Fig. 12).

In a normal ventilation scan, the radiotracer washes into the lungs homogeneously, usually after the first deep breath. Most of the radiotracer will normally wash out of the lungs within two minutes (Fig. 12).

Figure 12 Normal lung ventilation scan, first breath through washout.

In a normal ventilation scan, the radiotracer washes into the lungs homogeneously, usually after one deep breath (far left image). Most of the radiotracer will normally wash out of the lungs within two minutes (far right image). These four images show normal homogeneous wash-in followed by normal rapid washout.

![]() Pulmonary emboli should produce a segmental mismatch on the V/Q scan in which ventilation is maintained but perfusion is absent. Depending on the number and size of defects, correspondence between the ventilation and perfusion scans and the appearance of the chest radiograph, the results of the lung scan are categorized as being normal, low, intermediate, or high probability for pulmonary embolism (Fig. 13).

Pulmonary emboli should produce a segmental mismatch on the V/Q scan in which ventilation is maintained but perfusion is absent. Depending on the number and size of defects, correspondence between the ventilation and perfusion scans and the appearance of the chest radiograph, the results of the lung scan are categorized as being normal, low, intermediate, or high probability for pulmonary embolism (Fig. 13).

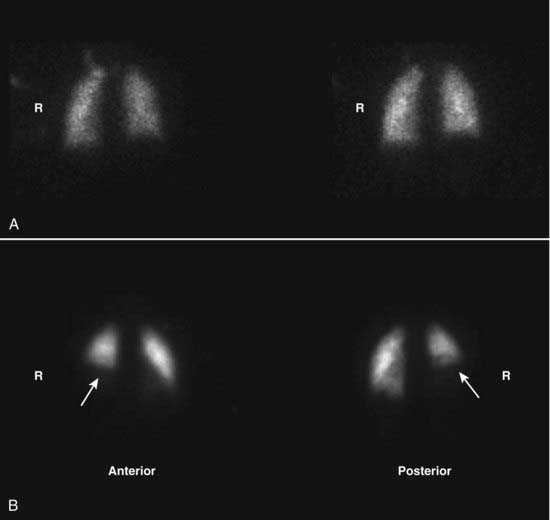

Figure 13 Pulmonary embolus on ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan.

A, The ventilation scan is normal. B, A large photopenic defect is seen at the right lung base (white arrows) on the perfusion scan. There is a mismatch between the ventilation and perfusion scans since the abnormality is present on one but not the other. Pulmonary emboli should produce a segmental mismatch like this on the V/Q scan in which ventilation is maintained but perfusion is absent.

Not surprisingly, the combination of a relatively low clinical suspicion of PE and a low probability lung scan effectively excludes PE (<5% will actually have a pulmonary embolism). The combination of a high clinical suspicion for PE and a high probability V/Q scan almost certainly indicates the presence of a PE (>95%). Unfortunately, there still is a majority of patients remaining who have an intermediate clinical likelihood of having PE and intermediate lung scan findings who may require another type of study.

Not surprisingly, the combination of a relatively low clinical suspicion of PE and a low probability lung scan effectively excludes PE (<5% will actually have a pulmonary embolism). The combination of a high clinical suspicion for PE and a high probability V/Q scan almost certainly indicates the presence of a PE (>95%). Unfortunately, there still is a majority of patients remaining who have an intermediate clinical likelihood of having PE and intermediate lung scan findings who may require another type of study.Cardiac Scans

Nuclear myocardial scans are used to detect myocardial ischemia and infarction. The examinations typically consist of both perfusion and ECG-gated, wall-motion studies. The studies can also determine left ventricular ejection fraction, regional wall motion, and end-systolic left ventricular volume.

Nuclear myocardial scans are used to detect myocardial ischemia and infarction. The examinations typically consist of both perfusion and ECG-gated, wall-motion studies. The studies can also determine left ventricular ejection fraction, regional wall motion, and end-systolic left ventricular volume. Nuclear myocardial imaging is associated with an excellent predictive value in that normal scan results are associated with an annual rate of severe cardiac events (myocardial infarction or cardiac death) of less than 1%.

Nuclear myocardial imaging is associated with an excellent predictive value in that normal scan results are associated with an annual rate of severe cardiac events (myocardial infarction or cardiac death) of less than 1%. Myocardial perfusion scanning

Myocardial perfusion scanning

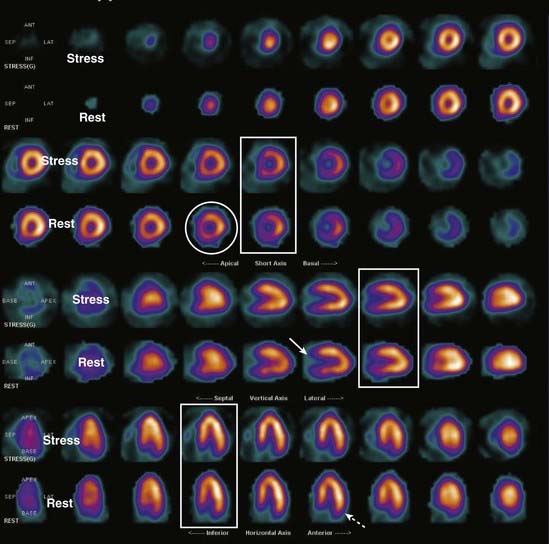

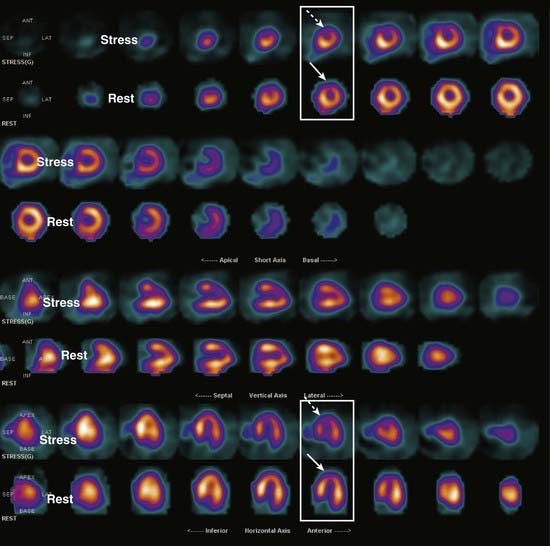

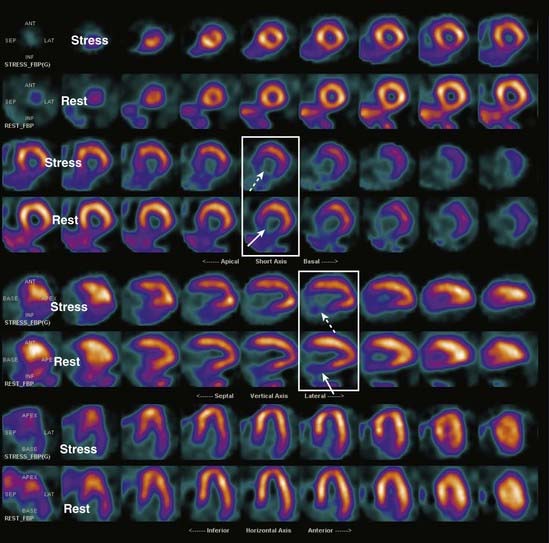

Figure 14 Normal cardiac scan.

Images are displayed in a standardized format, usually in color. In the short-axis view, the wall segments form a circle (white circle). In the vertical long-axis view, there is a U shape with the opening to the right (solid white arrow). In the horizontal long-axis view, the opening of the U points downward (dotted white arrow). In any given image, wall thickness is uniform. By convention, the first row of each set of images is the stress portion of the test and the second row is the rest portion of the test for those same images. Normally, each paired set of stress and rest images looks the same (white rectangles).

Wall motion

Wall motion

Figure 15 Left anterior descending coronary artery ischemia.

Compare the sets of images in the two rectangles. There is a wall defect on the stress portions of the test (dotted white arrows point to thinning of the wall) which improves with rest (solid white arrows). Since the defect reverses with rest, this is more characteristic of ischemia than infarct. The defect is in the distribution of the left anterior descending coronary artery.

Figure 16 Basal inferior infarct.

Once again, compare the pairs of stress and rest images in the white rectangles. There is a fixed defect in the wall which remains on both the stress (dotted white arrows) and resting images (solid white arrows). The lack of reversibility is consistent with infarction of the inferior wall.

Thyroid Scintigraphy

Thyroid scans are used to determine the functioning of thyroid nodules, to help differentiate Graves’ disease from toxic nodular goiter (Plummer’s disease), to diagnose thyrotoxicosis, to image metastases from thyroid cancer, and sometimes to establish a mediastinal mass as being thyroid in origin.

Thyroid scans are used to determine the functioning of thyroid nodules, to help differentiate Graves’ disease from toxic nodular goiter (Plummer’s disease), to diagnose thyrotoxicosis, to image metastases from thyroid cancer, and sometimes to establish a mediastinal mass as being thyroid in origin. A thyroid scan is an image of the thyroid gland. Thyroid scans can be combined with a measurement of radioactive thyroid uptake, which is a measure of the gland’s functional ability to concentrate and clear iodine.

A thyroid scan is an image of the thyroid gland. Thyroid scans can be combined with a measurement of radioactive thyroid uptake, which is a measure of the gland’s functional ability to concentrate and clear iodine. Patients with hyperthyroidism will show elevated thyroid uptakes whereas patients with hypothyroidism will show decreased uptakes. The normal range of thyroid uptake varies but is generally between 10% and 35%. Radioactive uptake studies have been largely replaced by blood tests for thyroxine (T4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

Patients with hyperthyroidism will show elevated thyroid uptakes whereas patients with hypothyroidism will show decreased uptakes. The normal range of thyroid uptake varies but is generally between 10% and 35%. Radioactive uptake studies have been largely replaced by blood tests for thyroxine (T4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Thyroid scans are done using either radioactive iodine or technetium 99m pertechnetate. Both iodine and pertechnetate are trapped in the thyroid gland. The radiopharmaceutical is most commonly administered by mouth or sometimes intravenously.

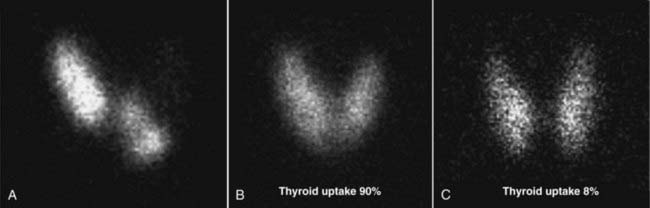

Thyroid scans are done using either radioactive iodine or technetium 99m pertechnetate. Both iodine and pertechnetate are trapped in the thyroid gland. The radiopharmaceutical is most commonly administered by mouth or sometimes intravenously. The normal thyroid gland is butterfly-shaped and is homogeneous in its uptake of radiotracer. Nodules of increased activity will show increased uptake (hot nodules) compared to the remainder of the thyroid, whose function may be suppressed by the hot nodule. Nodules of decreased activity will show decreased or no uptake (cold nodules) relative to the remainder of the thyroid gland (Fig. 17).

The normal thyroid gland is butterfly-shaped and is homogeneous in its uptake of radiotracer. Nodules of increased activity will show increased uptake (hot nodules) compared to the remainder of the thyroid, whose function may be suppressed by the hot nodule. Nodules of decreased activity will show decreased or no uptake (cold nodules) relative to the remainder of the thyroid gland (Fig. 17).

Thyroid nodules are common. They are more common in women than men. They increase in frequency with advancing age, so a solitary nodule in a younger person is of more concern than in an older individual.

Thyroid nodules are common. They are more common in women than men. They increase in frequency with advancing age, so a solitary nodule in a younger person is of more concern than in an older individual. About 85% of all thyroid nodules are cold, and 15% are hot or “warm.” The overwhelming percentage of cold nodules (85%) are benign, while 95% of hot nodules are benign. Ultrasound, combined with fine needle aspiration, is used to definitively diagnose thyroid cancer in cold nodules (Fig. 18).

About 85% of all thyroid nodules are cold, and 15% are hot or “warm.” The overwhelming percentage of cold nodules (85%) are benign, while 95% of hot nodules are benign. Ultrasound, combined with fine needle aspiration, is used to definitively diagnose thyroid cancer in cold nodules (Fig. 18).

Figure 18 Hot and cold nodules on thyroid scan.

Thyroid nodules are common, frequently multiple, and occur especially in older women. A solitary nodule in a younger person is of more concern for malignancy than in an older individual. About 85% of all thyroid nodules are cold, and 15% are hot or “warm.” This is a multinodular gland with a hot nodule (solid white arrow) in the right lobe and a cold nodule (dotted white arrow) occupying the left lobe. These lesions are benign.

An enlarged thyroid gland is called a goiter. There are many causes of a thyroid goiter, including nontoxic goiters (multinodular colloid goiters), Graves’ disease, Plummer’s disease (toxic nodular goiter), and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

An enlarged thyroid gland is called a goiter. There are many causes of a thyroid goiter, including nontoxic goiters (multinodular colloid goiters), Graves’ disease, Plummer’s disease (toxic nodular goiter), and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. In nontoxic multinodular colloid goiters, the gland is enlarged and takes up radiotracer heterogeneously. In Graves’ disease the gland is enlarged with uniform and intense increased uptake. The thyroid may also be enlarged in the early phase of thyroiditis (Fig. 19).

In nontoxic multinodular colloid goiters, the gland is enlarged and takes up radiotracer heterogeneously. In Graves’ disease the gland is enlarged with uniform and intense increased uptake. The thyroid may also be enlarged in the early phase of thyroiditis (Fig. 19).

Figure 19 Nontoxic goiter, Graves’, and thyroiditis on thyroid scans of different patients.

A, In nontoxic, multinodular colloid goiters, the gland is enlarged and takes up radiotracer heterogeneously. B, Graves’ disease demonstrates an enlarged gland with uniform and intense distribution of the tracer. The thyroid uptake is elevated due to hyperthyroidism. C, The thyroid may also be enlarged in the early phase of thyroiditis. The uptake here is low due to hypothyroidism.

Thyroid cancer typically presents as a dominant, solitary nodule. The presence of multiple nodules reduces the likelihood of malignancy (Fig. 20).

Thyroid cancer typically presents as a dominant, solitary nodule. The presence of multiple nodules reduces the likelihood of malignancy (Fig. 20).

Thyroid cancer typically presents as a dominant, solitary nodule. The presence of multiple nodules reduces the likelihood of malignancy. There is a single, large cold nodule in the right lower pole of the gland (white arrow). Since most cold nodules are benign, confirmatory ultrasound with a fine needle biopsy is frequently performed.

Radioisotope scans can also demonstrate metastases from thyroid carcinoma distant from the gland itself. Follicular and papillary thyroid carcinomas may show increased tracer uptake in the lungs, lymph nodes, and skeleton (Fig. 21).

Radioisotope scans can also demonstrate metastases from thyroid carcinoma distant from the gland itself. Follicular and papillary thyroid carcinomas may show increased tracer uptake in the lungs, lymph nodes, and skeleton (Fig. 21).

Figure 21 Pulmonary thyroid metastases visualized with radioiodine.

Radioisotope scans can demonstrate metastases from thyroid carcinoma distant from the gland itself, especially in follicular and papillary thyroid carcinomas. These images are of the chest in a patient who received radioiodine. There are multiple foci of increased radioiodine uptake in the lungs (white arrows), metastatic from a papillary carcinoma of the thyroid (not imaged here).

Radioiodine is also used in much higher doses than for diagnostic purposes for the ablation of the gland in Graves’ disease and for the treatment of thyroid cancer. Iodine 131 (I-131) is usually utilized as the radioisotope for treatment. Radioiodine is also used in the treatment of thyroid carcinoma metastases from primary tumors that demonstrate the ability to take up radioisotope.

Radioiodine is also used in much higher doses than for diagnostic purposes for the ablation of the gland in Graves’ disease and for the treatment of thyroid cancer. Iodine 131 (I-131) is usually utilized as the radioisotope for treatment. Radioiodine is also used in the treatment of thyroid carcinoma metastases from primary tumors that demonstrate the ability to take up radioisotope.HIDA Scans

Cholescintigraphy is performed using technetium 99m, which was originally coupled to iminodiacetic acid (IDA). This was referred to as a HIDA scan, in which the “H” stands for “hepatic” or “hepatobiliary.” Even though other radiopharmaceuticals besides iminodiacetic acid may now be used for the test, it is still often referred to as a HIDA scan. The HIDA scan is the most frequently used nuclear medicine liver study.

Cholescintigraphy is performed using technetium 99m, which was originally coupled to iminodiacetic acid (IDA). This was referred to as a HIDA scan, in which the “H” stands for “hepatic” or “hepatobiliary.” Even though other radiopharmaceuticals besides iminodiacetic acid may now be used for the test, it is still often referred to as a HIDA scan. The HIDA scan is the most frequently used nuclear medicine liver study. HIDA scans are generally indicated in cases of suspected acute cholecystitis in which an ultrasound examination may be equivocal. They are also used to demonstrate postoperative biliary leaks.

HIDA scans are generally indicated in cases of suspected acute cholecystitis in which an ultrasound examination may be equivocal. They are also used to demonstrate postoperative biliary leaks. The patient has nothing by mouth for 3 to 4 hours before the study. After intravenous injection, the radiopharmaceutical binds to protein, is taken up by the liver, and then rapidly excreted from the liver, similar to bile.

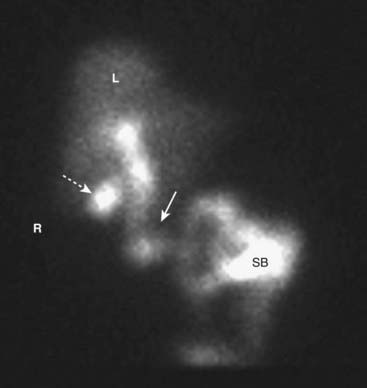

The patient has nothing by mouth for 3 to 4 hours before the study. After intravenous injection, the radiopharmaceutical binds to protein, is taken up by the liver, and then rapidly excreted from the liver, similar to bile. In a normal HIDA scan, the bile ducts contain radiotracer within 10 minutes and there is radiotracer in the duodenum by 60 minutes, indicating patency of the common bile duct. Filling of the normal gallbladder occurs within 30 to 60 minutes, which confirms the patency of the cystic duct. Delayed images in several hours are usually obtained to reduce false positive results (Fig. 22).

In a normal HIDA scan, the bile ducts contain radiotracer within 10 minutes and there is radiotracer in the duodenum by 60 minutes, indicating patency of the common bile duct. Filling of the normal gallbladder occurs within 30 to 60 minutes, which confirms the patency of the cystic duct. Delayed images in several hours are usually obtained to reduce false positive results (Fig. 22).

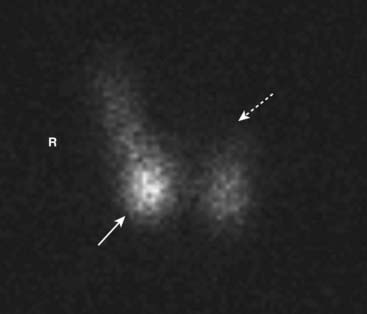

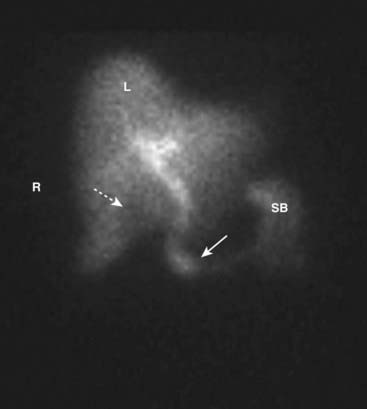

In a normal HIDA scan, the bile ducts (solid white arrow) contain radiotracer within 10 minutes, and there is radiotracer in the duodenum and small bowel (SB) by 60 minutes, indicating patency of the common bile duct. Filling of the normal gallbladder (dotted white arrow) occurs within 30 to 60 minutes, which confirms the patency of the cystic duct. Delayed images in several hours may be obtained to reduce false positive results. (R, Patient’s right side; L, liver.)

Cholescintigraphy is very sensitive and extremely specific for acute cholecystitis. One of its disadvantages is that it can take several hours to perform and an acutely ill patient may need a diagnosis sooner. To shorten the time needed to complete the study, morphine sulphate can be administered intravenously. Morphine causes constriction of the sphincter of Oddi, increasing pressure in the common duct and speeding the filling of the cystic duct. The gallbladder should fill normally within 30 minutes of morphine administration (Fig. 23).

Cholescintigraphy is very sensitive and extremely specific for acute cholecystitis. One of its disadvantages is that it can take several hours to perform and an acutely ill patient may need a diagnosis sooner. To shorten the time needed to complete the study, morphine sulphate can be administered intravenously. Morphine causes constriction of the sphincter of Oddi, increasing pressure in the common duct and speeding the filling of the cystic duct. The gallbladder should fill normally within 30 minutes of morphine administration (Fig. 23).

Figure 23 HIDA scan in cholecystitis.

The gallbladder does not fill with radiotracer. Instead there is a photopenic area of the liver (L) in the location of the gallbladder (dotted white arrow). There is no filling of the cystic duct but there is filling of the common duct (solid white arrow) and runoff into the small bowel (SB). Obstruction of the cystic duct and nonfilling of the gallbladder in a symptomatic patient is consistent with acute cholecystitis. (R, Patient’s right side.)

Cholescintigraphy is also used to demonstrate bile leaks in patients who have undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy, liver transplant, or trauma. After the radiopharmaceutical is injected, the abdomen is scanned to image radiotracer outside of the normal confines of the biliary system (Fig. 24).

Cholescintigraphy is also used to demonstrate bile leaks in patients who have undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy, liver transplant, or trauma. After the radiopharmaceutical is injected, the abdomen is scanned to image radiotracer outside of the normal confines of the biliary system (Fig. 24).

Figure 24 HIDA scan showing bile leak.

Cholescintigraphy is also used to demonstrate bile leaks in patients who have undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy, liver transplant, or trauma. After the radiopharmaceutical is injected, the abdomen is scanned to image radiotracer outside of the normal confines of the biliary system. In this patient, radiotracer is seen in the gallbladder fossa (solid white arrow) and the “bulb” of a drain inserted at the site of the cholecystectomy (dotted white arrow). Visualization of the tracer outside of the ductal system or bowel is an indication of a bile leak. (R, Patient’s right side; L, liver.)

Gastrointestinal Bleeding Scans

Localization of bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract can be problematic using either endoscopy or imaging studies.

Localization of bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract can be problematic using either endoscopy or imaging studies. Utilizing technetium 99m coupled to red blood cells (RBCs), the site of bleeding can be localized. An initial flow study is frequently performed and static imaging of the abdomen usually lasts for about 90 minutes. Only about 2-3 cc of extravasated blood is needed for detection (Fig. 25).

Utilizing technetium 99m coupled to red blood cells (RBCs), the site of bleeding can be localized. An initial flow study is frequently performed and static imaging of the abdomen usually lasts for about 90 minutes. Only about 2-3 cc of extravasated blood is needed for detection (Fig. 25).

Figure 25 Normal gastrointestinal bleeding scan.

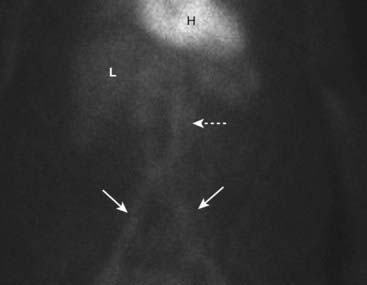

The patient’s own red blood cells are labeled with a radiotracer and the abdomen is scanned. Activity may normally be found in the heart (H), liver (L), aorta (dotted white arrow), and iliac arteries (solid white arrows). Abnormal studies will show a focus of increased activity in the bowel, which will move on serial images due to the peristaltic motion of the gut.

Abnormal studies will demonstrate an extravascular but intraluminal focus of increased radiotracer uptake that increases over time. Since blood irritates the intestine, peristalsis is more rapid than normal. The focus of increased uptake must move through the bowel over the course of serial images (Fig. 26).

Abnormal studies will demonstrate an extravascular but intraluminal focus of increased radiotracer uptake that increases over time. Since blood irritates the intestine, peristalsis is more rapid than normal. The focus of increased uptake must move through the bowel over the course of serial images (Fig. 26).

Figure 26 Abnormal bleeding scan.

An abnormal collection of radiotracer is seen in the right lower quadrant (white oval) in this patient bleeding from right-sided diverticulosis. The focus of increased uptake moved through the large bowel on serial images. Radiotracer activity is seen in the major vessels (Ao, Aorta; I, iliac arteries), the stomach (S) and the liver (L).

Positron Emission Tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans operate on a molecular level to produce three-dimensional images that depict the body’s biochemical and metabolic processes. They are performed using a positron (positive electron) producing radioisotope attached to a targeting pharmaceutical.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans operate on a molecular level to produce three-dimensional images that depict the body’s biochemical and metabolic processes. They are performed using a positron (positive electron) producing radioisotope attached to a targeting pharmaceutical. Radioisotopes used in PET imaging include fluorine-18, carbon-11, and oxygen-15. These isotopes have short half-lives (all less than 2 hours) and, since they are produced in a cyclotron, earlier PET scanners required an on-site cyclotron. Fluorine-18 has the benefit of allowing production in an off-site cyclotron.

Radioisotopes used in PET imaging include fluorine-18, carbon-11, and oxygen-15. These isotopes have short half-lives (all less than 2 hours) and, since they are produced in a cyclotron, earlier PET scanners required an on-site cyclotron. Fluorine-18 has the benefit of allowing production in an off-site cyclotron. The most commonly used target molecule in PET scanning is an analog of glucose called fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) (called FDG-PET). The concentration of this glucose analog in bodily tissues gives a measure of metabolic activity.

The most commonly used target molecule in PET scanning is an analog of glucose called fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) (called FDG-PET). The concentration of this glucose analog in bodily tissues gives a measure of metabolic activity. Many PET scanners incorporate the presence of a CT scanner, which allows for the fusion (called coregistration) of the functional PET dataset on the anatomical dataset of CT scan images. The PET and CT scans are done sequentially without moving the patient, which minimizes patient motion between the two studies and improves the quality of the image.

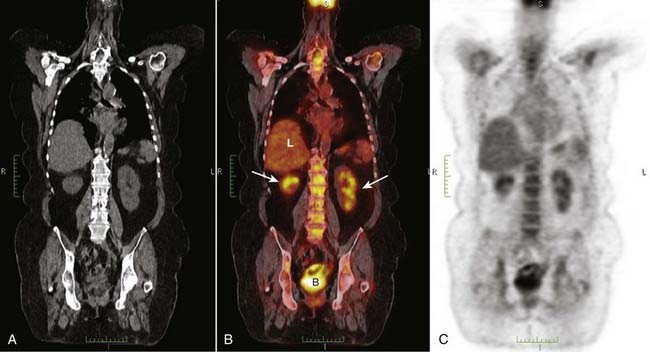

Many PET scanners incorporate the presence of a CT scanner, which allows for the fusion (called coregistration) of the functional PET dataset on the anatomical dataset of CT scan images. The PET and CT scans are done sequentially without moving the patient, which minimizes patient motion between the two studies and improves the quality of the image. By fusing the PET and CT images, the anatomical location of the functional abnormality is determined (Fig. 27).

By fusing the PET and CT images, the anatomical location of the functional abnormality is determined (Fig. 27).

Figure 27 PET/CT fusion image.

By fusing the PET and CT images, the anatomical location of the functional abnormality can be determined. The CT scan (A) is superimposed on the PET image (C) to form the PET/CT fusion image (B). Uptake of FDG is depicted by varying intensities of red. Normal uptake is seen in the liver (L) and normal excretion is through the kidneys (white arrows) into the bladder (B). The more concentrated the uptake, the more intense the red color.

Uses of Pet Scans

PET scanning is most often used in the diagnosis and treatment follow-up of cancer. It is frequently used to locate hidden metastases from a known tumor or to detect recurrence. Oncologic PET scans make up about 90% of the clinical use of PET.

PET scanning is most often used in the diagnosis and treatment follow-up of cancer. It is frequently used to locate hidden metastases from a known tumor or to detect recurrence. Oncologic PET scans make up about 90% of the clinical use of PET.

Because of their ability to measure function, PET scans are also used in analyzing brain and heart function and to measure regional blood flow. In the brain, areas of high radiotracer activity correspond to areas of increased brain activity. By using compounds that bind to certain neuroreceptors in the brain, PET has been used to study psychiatric disorders and substance abuse. It has also been used extensively in Alzheimer disease and epilepsy.

Because of their ability to measure function, PET scans are also used in analyzing brain and heart function and to measure regional blood flow. In the brain, areas of high radiotracer activity correspond to areas of increased brain activity. By using compounds that bind to certain neuroreceptors in the brain, PET has been used to study psychiatric disorders and substance abuse. It has also been used extensively in Alzheimer disease and epilepsy. In the heart, PET scans are being used in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, in part because they offer superior resolution to perfusion imaging. Completely infarcted areas can be differentiated from ischemia utilizing both perfusion and PET imaging. This differentiation is important in determining a course of treatment because there is little benefit in revascularizing completely infarcted muscle.

In the heart, PET scans are being used in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, in part because they offer superior resolution to perfusion imaging. Completely infarcted areas can be differentiated from ischemia utilizing both perfusion and PET imaging. This differentiation is important in determining a course of treatment because there is little benefit in revascularizing completely infarcted muscle.Safety Issues and Pet Scans

PET scans expose the body to ionizing radiation. When combined with a CT scan that also utilizes ionizing radiation, the radiation dose can be significant. As with all diagnostic tests that utilize ionizing radiation, the benefits provided by the data obtained from the test must be weighed against its potential risks.

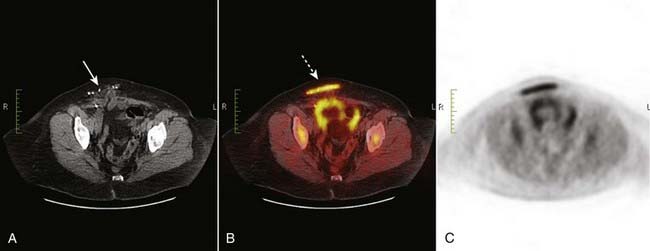

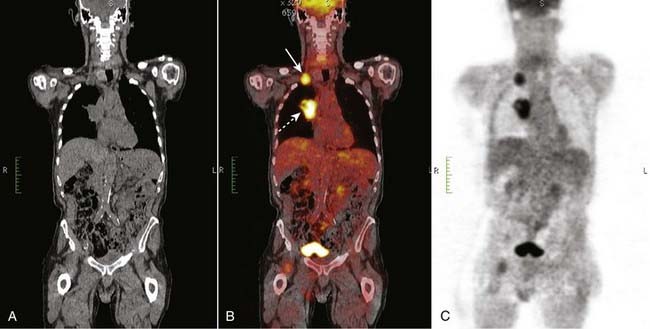

PET scans expose the body to ionizing radiation. When combined with a CT scan that also utilizes ionizing radiation, the radiation dose can be significant. As with all diagnostic tests that utilize ionizing radiation, the benefits provided by the data obtained from the test must be weighed against its potential risks. False-positive findings may occur with inflammatory processes, in benign neoplasms, and in hyperplastic but benign tissue, all of which are FDG avid (Fig. 28).

False-positive findings may occur with inflammatory processes, in benign neoplasms, and in hyperplastic but benign tissue, all of which are FDG avid (Fig. 28).

Figure 28 FGG avid scar from hernia repair.

PET scans are most often used to diagnose or confirm malignancy. False-positive findings may occur with inflammatory processes, in benign neoplasms, and in hyperplastic but benign tissue, all of which are FDG avid. (A) This patient had previously undergone a hernia repair on the right side (solid white arrow). The PET/CT fusion image (B) shows intense uptake in the inflammatory reaction surrounding the site of the repair (dotted white arrow).

Pet Scan Images

There is physiologic (normal) uptake of FDG in the salivary glands, thyroid, brown fat, thymus, the liver, GI tract, kidneys and urinary bladder, and the uterus (see Fig. 27).

There is physiologic (normal) uptake of FDG in the salivary glands, thyroid, brown fat, thymus, the liver, GI tract, kidneys and urinary bladder, and the uterus (see Fig. 27). FDG avid lesions are those that show abnormally increased uptake of the radiopharmaceutical (Figs. 29 and 30).

FDG avid lesions are those that show abnormally increased uptake of the radiopharmaceutical (Figs. 29 and 30).

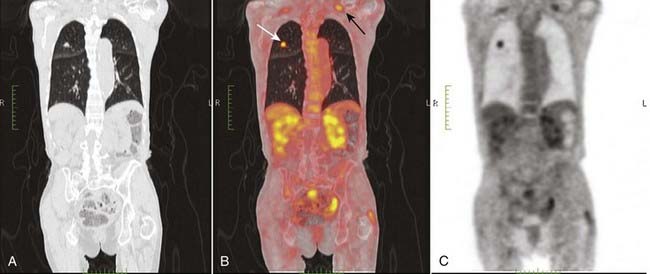

Figure 29 Positive PET scan, bronchogenic carcinoma.

An FDG avid lesion is seen in the right upper lobe (white arrow) on this coronal reformatted PET/CT scan (B) confirming what was suspected to be the malignant nature of this lesion. This was an adenocarcinoma of the lung. A metastatic lymph node is seen in the left supraclavicular region (black arrow).

Figure 30 Positive PET scan, bronchogenic carcinoma with metastases.

A large right hilar mass (dotted white arrow) is FDG avid and represented a bronchogenic carcinoma (B). Less evident was a right supraclavicular lymph node metastasis (solid white arrow). PET scans are especially helpful in detecting occult metastases.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Nuclear Medicine: Understanding the Principles and Recognizing the Basics

A radioactive isotope (radioisotope) is a naturally or artificially produced, unstable form of an element that emits radiation from its nucleus as it decays.

Radiopharmaceuticals are combinations of radioisotopes attached to a pharmaceutical that has binding properties which allow it to concentrate in certain body tissues.

Unstable isotopes attempt to reach stability by the process of splitting (fission), or by emitting particles (alpha or beta particles) and/or energy (gamma rays) in the form of radiation. Positively charged electrons are called positrons.

Physical half-life is the time required for the number of radioactive atoms in a sample to decrease by 50% and is a property inherent to the radioisotope. Most radioisotopes for medical use must have half-lives of hours or days.

The most widely used radioisotope is technetium 99m with a half-life of 6 hours. It decays by emitting low-energy gamma rays.

A gamma camera uses one or more scintillation detectors made of crystals that scintillate (luminesce) in response to gamma rays emitted from the patient.

Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging is performed by using a gamma camera to acquire multiple two-dimensional (2D) images from multiple angles, which are then reconstructed by computer into a three-dimensional (3D) dataset.

Bone scans are the screening method of choice for the detection of osseous metastatic disease. Tc 99m MDP deposits in the greatest concentration in those areas of greatest bone turnover. Radionuclide bone scanning is sensitive (60% to 90%) for metastases, but not specific.

CT pulmonary angiography (CT-PA) has largely replaced nuclear scans in the diagnosis of pulmonary thromboembolic disease. If the chest radiograph is normal, then V/Q scanning may be diagnostic. If the chest radiograph is abnormal, a CT-PA is usually performed.

Pulmonary emboli should produce a segmental mismatch on the V/Q scan in which perfusion is absent but ventilation is maintained.

Nuclear cardiac scans are used to detect myocardial ischemia and infarction and to determine left ventricular ejection fraction, regional wall motion, and end-systolic left ventricular volume.

Thyroid scans are used to determine the functioning of thyroid nodules, to help differentiate Graves’ disease from toxic nodular goiters and thyrotoxicosis, and to image metastases from thyroid cancer. Thyroid scans are frequently combined with a functional measurement of thyroid activity called thyroid uptake.

The most frequently used biliary scan is generically called a HIDA scan. HIDA scans are generally indicated in cases of suspected acute cholecystitis in which an ultrasound examination may be equivocal. They are also used to demonstrate postoperative biliary leaks.

Nuclear GI bleeding scans can help in the localization of bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract by imaging the abdomen after administering tagged red blood cells to the patient.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans operate on a molecular level to produce three-dimensional images that depict the body’s biochemical and metabolic processes. PET scanning is most often used in the diagnosis and treatment follow-up of cancer but they are also used in cardiac and brain imaging.

The most commonly used target molecule in PET scanning is an analog of glucose called fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) (called FDG-PET).

Many PET scanners incorporate the presence of a CT scanner, which allows for the fusion (called coregistration) of the functional PET dataset on the anatomical dataset of CT scan images.