Chapter 8 Musculoskeletal disorders

Benign familial joint hypermobility syndrome

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

Regional examination of the musculoskeletal system (REMS)

Rigid/semi-rigid, functional orthoses

Seropositive inflammatory arthritis

INTRODUCTION

This chapter is intended to provide an introduction for readers either potentially or actually involved in the care of the foot in patients with rheumatic conditions. An overview of the medical management is provided because foot pathologies do not normally present in isolation in these patients and so the systemic context is important. However, the chapter is about the foot and so focuses mainly on the foot conditions, the processes underlying them and the treatment options available. The evidence supporting many of the therapies for disorders of the foot in rheumatology is often weaker than would be desirable. This chapter represents, therefore, a digest of available literature, combined with the authors’ experience of clinical practice and research within an academic multidisciplinary rheumatology team supported by a comprehensive foot health service.

DEFINING RHEUMATOLOGY AND THE MUSCULOSKELETAL DISEASES

Rheumatology practice covers a heterogeneous range of more than 200 disorders with varied aetiologies, and which affect joints, bones, muscles and soft tissues (Linaker et al 1999, Symmons et al 2002). The rheumatic disorders have a variety of systemic features, but their common feature is their effect on the musculoskeletal system. Those working with foot problems are probably familiar with disorders arising from purely biomechanical and local factors, and these disorders are dealt with elsewhere in this book. This chapter focuses on the broader rheumatic diseases affecting the feet and their associated systemic or extended local disease processes. Many of the disorders seen in rheumatology practice are the consequence of a disordered immune response, and are therefore sometimes referred to as immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Typical examples of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases are RA, the spondyloarthropathies, and the connective tissue diseases such as lupus and scleroderma (described later). Other systemic presentations include diseases caused by disordered metabolism, such as gout and osteoporosis; and complex, multifactorial disorders such as OA.

GENERAL EPIDEMIOLOGY OF RHEUMATIC CONDITIONS

Approximately 1 in 7 adults in the UK has ongoing musculoskeletal symptoms, with some 1 in 20 people suffering moderate to severe disability secondary to a musculoskeletal disorder (Symmons et al 2002). The prevalence of musculoskeletal disease increases steadily with age, and by the age of 75 years can be as high as one person in three (Urwin et al 1998, Symmons et al 2002). Musculoskeletal pain also presents in multiple sites, and only one-third of people report their musculoskeletal pain to be confined to a single joint (Urwin et al 1998). Unsurprisingly, the degree of impact on quality of life increases as the number of affected sites increases (Urwin et al 1998).

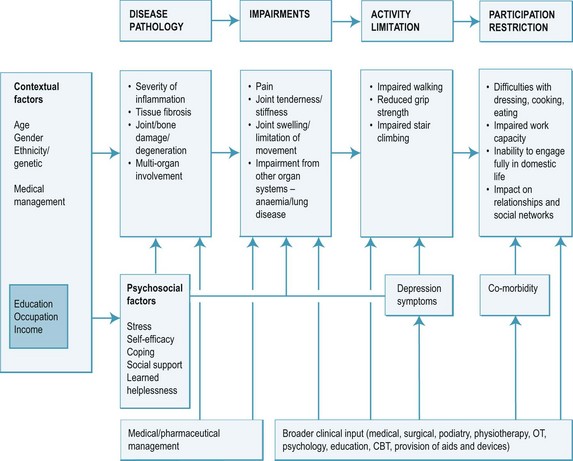

The disability pathway from the underpinning local joint inflammation through to the impact on quality of life is well described for arthritis, and is summarised in Figure 8.1. Controlling symptoms and the effects of disease on quality of life are the focus of much of the therapeutic process. It should be remembered, however, that the disability pathway is influenced not only by disease factors, and that approximately one-quarter of disability is predicted by a range of modifying factors such as age, gender, lifestyle, work demands and psychological status (Escalante & Del Rincon 1999, 2002).

BURDEN OF DISEASE

The burden of musculoskeletal disability to the health system is significant, with musculoskeletal conditions accounting for about one in five of all GP consultations, a proportion that continues to increase (Arthritis Research Campaign 2002, Symmons et al 2002). The musculoskeletal diseases are to some degree a social problem, because the prevalence is significantly higher in more deprived socio-economic groups and in workers engaged in more physical activities (Arthritis Research Campaign 2002, Urwin et al 1998).

The direct cost to the UK health service is approximately £5.5 billion each year, but indirect costs (such as the 206 million days a year lost to work, reduced incomes, social security and mortality) raise the total cost to the UK economy to £18 billion per year (Arthritis Research Campaign 2002).

THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF FOOT PROBLEMS GENERALLY AND IN RHEUMATOLOGY

Nearly one-quarter of all people aged over 55 years report ongoing foot pain, which in the majority of cases leads to impairment to daily activities (Benvenuti et al 1995, Chen et al 2003, Gorter et al 2001, Leveille et al 1998, Thomas et al 2004). Some 20–24% of all adults have had foot pain in the past month and some 60% have had foot pain in the past 6 months, with the foot pain causing measurable disability in half of these cases (Garrow et al 2004). Musculoskeletal disorders account for more than three-quarters of all foot pain (Gorter et al 2000) or, in other words, for foot pain in up to 7% of the total population (Cunningham & Kelsey 1984).

The incidence of foot problems is known to increase with age, and to be as much as five times higher in females than males (Benvenuti et al 1995, Black & Hale 1987, Dunn et al 2004, Garrow et al 2004, Leveille et al 1998, Munro & Steele 1998). Foot pathology often also coexists with other musculoskeletal morbidity such as knee or hip pain (Gorter et al 2000, Leveille et al 1998, Munro & Steele 1998, Odding et al 1995), and this should be considered in assessment and treatment planning. As well as the musculoskeletal manifestations themselves, plantar hyperkeratoses have been found in 66% of people with musculoskeletal or connective tissue disease, digital lesions in 24% and ulcerations in as many as 17% (Port et al 1980).

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF DEVELOPMENTS IN MEDICAL RHEUMATOLOGY

In many rheumatic diseases, the classical approach of slowly escalating drug therapy has been superseded by a new paradigm of early and aggressive treatment, and combination therapies using disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). This change in approach has been further enhanced in recent years by the development of a new range of pharmaceuticals, the so-called ‘biological’ immunotherapies, which provide a highly effective treatment option for patients who do not respond adequately to conventional therapies. The significant medical advances are also reflected in the management of rheumatology patients by allied health professionals, as the emphasis moves from compassionate management of physical decline to more dynamic and proactive approaches.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT IN RHEUMATOLOGY – OVERVIEW ACROSS DISEASES

Medical management in rheumatology has undergone nothing short of a revolution in recent years. While the non-inflammatory conditions such as OA continue to be managed according to fairly traditional principles, treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases has been, quite literally, turned on its head.

Between the 1950s and the mid-1990s, patients with inflammatory arthritis would be managed according to the severity of presenting symptoms, using what was described as a ‘treatment pyramid’, where drug therapy was escalated slowly and incrementally in response to treatment failure (Cannella & O’Dell 2003, Fries et al 1996, Pincus et al 1999). High doses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) would be used, with doses increasing until patients were no longer able to tolerate therapy. When disease control was inadequate using NSAIDS, other disease-modifying drugs such as the antimalarials, gold, penicillamine and sulfasalazine would be introduced sequentially to try to suppress the inflammation as far as practicable. These second-line DMARDs were often not introduced until 5–10 years of disease duration had passed and, as we now know, damage had already accrued (Wolfe et al 2001). In the 1990s, methotrexate came to prominence such that it became the recommended DMARD to be given early in the course of the disease, with rapidly escalating doses if response was suboptimal.

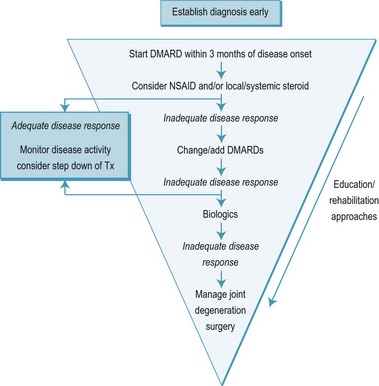

Furthermore, better understanding of the pathological processes involved, the discovery of the role of cytokines in the early 1980s, and the development of anti cytokine drugs in the past 10 years (Feldmann 2002) have led to a total paradigm shift. The new paradigm is known as the ‘inverted pyramid’ or ‘step-down bridge’ approach (Fries et al 1996, Pincus et al 1999) (Figure 8.2).

In the step-down approach early management is aggressive and combinations of DMARDs are used to suppress inflammation nearer to disease onset, so limiting irreversible joint damage (O’Dell 2004). There is compelling evidence that the new approach improves outcomes substantially in a range of immune-mediated arthropathies (Cannella & O’Dell 2003, Rao & Hootman 2004) and that the earlier that treatment is instigated the better (Bukhari et al 2003, Hazes 2003, Lard et al 2001, Puolakka et al 2004). The Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA) national standards of care for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) require that all patients with suspected inflammatory arthritis are seen by a rheumatology specialist within 12 weeks of first presentation, and preferably within 6 weeks (Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance 2004a).

In inflammatory arthritis, the goal at first presentation is to establish and maintain disease remission, and this can often be achieved with standard (i.e. traditional non-biological) therapies (Bukhari et al 2003). Patients are started on NSAIDs (ibuprofen, diclofenac, indometacin or cyclo-oxygenase-2 (cox-2) inhibitors, according to risk factors), which provide immediate reduction in pain and stiffness (O’Dell 2004). NSAIDs are not used in isolation, however, as they do not prevent erosions and joint damage and so do not alter long-term prognosis (Aletaha & Smolen 2002, American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002, Choy et al 2002, Fries et al 1996). Much has been made of the potential benefits offered by the new cox-2 selective NSAIDS, although the objective evidence suggests that the effectiveness of the cox-2 inhibitors is no greater than traditional (and cheaper) NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, naproxen and diclofenac, with benefits confined to slightly better tolerance (Garner et al 2004a,b). Importantly, new data emerging have indicated a potential for increasing the risk of cardiovascular events with cox-2 drugs, and one of this new class of NSAIDs (rofecoxib) has already been withdrawn from the market (Juni et al 2004). Prescribers are therefore advised to be cautious and to avoid these drugs in anyone with a high risk, or history, of cardiovascular disease (Fitzgerald 2004). Furthermore, it is now becoming clear that even traditional NSAIDs carry an increased risk of vascular disease. These developments have led to an aversion by physicians to prescribing NSAIDs – if they are prescribed the recommendation is for the smallest possible dose for the shortest possible time.

There is good evidence that instigation of DMARD therapy within 3 months of disease onset is highly effective in controlling immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002, O’Dell 2004), and so patients are normally started on a suitable DMARD immediately. The most commonly used DMARDs at present are methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine, with sulfasalazine becoming increasingly marginalised. Leflunomide is a new DMARD with good tolerability, which can be used in conjunction with methotrexate or as a fallback when patients cannot use methotrexate (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002, Olsen & Stein 2004; Osiri et al 2004). Methotrexate is usually the DMARD of first choice because of its significant therapeutic effects when used in isolation, and because of its adjunctive effects when used in combination with other DMARDs (O’Dell 2004, Verstappen et al 2003a,b). Methotrexate is the best tolerated DMARD for long-term therapy, and many patients use methotrexate for many years (O’Dell 1997, Rau et al 1997, Verstappen et al 2003). Used in this way, methotrexate is often referred to as an ‘anchor drug’ (Pincus et al 1999).

There is some controversy on the use of oral corticosteroids as a first-line treatment because of their wide ranging systemic side-effects. Recent high-profile studies on intensive treatment regimens have used oral steroids (BeST and TICORA) but their use is not widespread in the UK. Oral steroids are useful in early disease as a ‘bridging therapy’ before the DMARDs take effect, and, given systemically, for short-term suppression of disease flares (O’Dell 2004). Low-dose systemic steroid therapy may be required on an ongoing basis in some patients but the dose is kept to a minimum (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002).

The new, biological DMARDs inhibit cytokine activity high up in the inflammatory pathway and can be highly effective even in patients who have failed on conventional DMARD therapy (O’Dell 2004, Olsen & Stein 2004). The most common ‘biologicals’ are the agents active against tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) (etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade) and adalimumab (Humira)), although new ones are now appearing (Olsen & Stein 2004). The effect of anti-TNF therapy is often striking, with some patients showing a positive response within days or even hours. Biological DMARDs are expensive, however, costing £8,000 to £10,000 for a year of treatment, and so their publicly funded use is restricted to those patients with active disease who have already failed on conventional DMARDs. Because they demonstrate better efficacy than conventional DMARDS, a case is being made for their use in early disease (Emery & Seto 2003, Breedveld et al 2004), where it is contended that the significant reduction in (work-related) disability associated with biological therapy makes these therapies cost effective when viewed in the context of savings to the country from lost work days (9.4 million days, equivalent to £833 million a year for RA alone) (Arthritis Research Campaign 2002) and decreased dependence on the state benefits system.

Another family of therapies are drugs aimed at reducing the activity and number of B-cells, which are important mediators of the immune-mediated inflammatory response. Rituximab is now well established as a therapy for RA and connective tissue diseases, and good results are reported up to 30 weeks after initial injection without short-term immunocompromise (Edwards et al 2004, Tsokos 2004). Other biological therapies are emerging every year. Currently, the T-cell costimulation blocker abatacept is licensed for use in RA and the anti-interleukin-6 (anti-IL6) compound toclizumab newly available. It is likely that all these therapies will be restricted to those people who have failed on conventional (and cheaper) DMARDs but, common to all, there is an increased risk of infection and practitioners must keep this in mind when caring for patients on these drugs. We still do not know whether drugs such as those in the anti-TNF class will cause an increased tumour incidence with long-term therapy, but the initial indications are good (see box 8.1).

It is essential that those involved in the care of the feet of people with inflammatory arthritis are aware of the medication being taken by their patients, and the implications of the drug therapy. Patients with inflammatory arthritis are twice as likely as the general population to develop an infection, and there is a further increase in infection risk in patients taking DMARDs (Edwards et al 2004, Olsen & Stein 2004). Although hard evidence is conflicting there is a suggestion that patients undergoing biologic immunotherapy may be particularly at risk from infection, as they appear to be susceptible to unusually rapid progression. It is absolutely essential that the foot health clinician liaises with the rheumatologist where there is any risk of infection (e.g. from ulceration, or prior to minor surgery). Otter and Cryer (2004) have made the point well that this should not erode the practitioner’s autonomy, but it does allow the appropriate precautions to be taken – including antibiotic cover and, if necessary, temporary alteration of antirheumatic therapy (Olsen & Stein 2004).

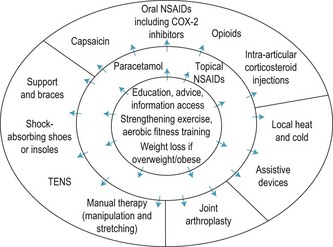

Medical management is usually combined with other approaches such as physical and occupational therapies. Exercise programmes have been found to improve outcomes in a range of rheumatological conditions, including low back pain, lupus, fibromyalgia and ankylosing spondylitis (Rao & Hootman 2004). Other physical therapies in widespread use are heat and cold therapies (baths, thermal packs etc.), therapeutic ultrasound, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), mobilisation and massage.

Patients with rheumatological disorders often have to live with chronic pain. It is important to recognise the limitations of medical management, and to ensure that the standard approaches are supplemented with specific strategies directed towards living with chronic pain or disability (Rao & Hootman 2004). Cognitive–behavioural strategies are important in enabling patients to understand the condition, and moderate their beliefs and behaviours (Rao & Hootman 2004).

THE FOOT IN RHEUMATOLOGY – OVERVIEW ACROSS DISEASES

Assessing the foot

There is no validated, standardised assessment for the foot in musculoskeletal conditions. A number of validated assessments that include the foot are used in medical practice, but podiatrists tend to use more individualised assessments.

The GALS (gait, arms, legs, spine) screen is now considered a minimum standard for all musculoskeletal assessments in medical rheumatology, and this includes at least an observational assessment of the feet. Where lower-limb involvement is suspected, this may be followed up using a new validated assessment, the REMS (regional examination of the musculoskeletal system) assessment, which is being introduced to the rheumatology community (Coady et al 2004). REMS includes a fairly detailed assessment of the feet, although it must be remembered that the GALS and REMS approaches are intended to be part of a general medical work-up and are inadequate for detailed assessment of the foot.

In the absence of a standardised foot assessment, we have developed a preferred protocol for foot assessment at the Leeds centre, which is based on a history–observation–examination (or look–feel–move) model (Box 8.2).

Box 8.2 The preferred protocol for assessing the foot in rheumatology at the authors’ centre

History

This assessment protocol provides most of the information required to inform a diagnosis and management plan. However, it is sometimes helpful to supplement this assessment with objective data from more ‘high-tech’ investigations, and patients may also be referred for objective, dynamic functional assessments, such as plantar pressure evaluations, or for radiographic imaging. Gait laboratory assessments are not mainstream outside of teaching centres and are not detailed here, but radiographic imaging is central to rheumatology practice and will be accessed widely by foot practitioners.

The plain radiograph is usually still the imaging modality of first choice, although it is increasingly being supplemented by a range of alternatives. Plain films will differentiate gross radiographic features, such as joint-space narrowing, osteophyte formation or periarticular erosion, but the images are limited to two dimensions. Menz et al (2007) have produced a useful atlas of radiographic classification of joint disease in the foot which may help to standardise interpretation. Plain films are limited in the new paradigm of early and aggressive intervention, however, because they are not sensitive to many of the changes that often occur early in the disease process (Devauchelle-Pensec et al 2002, Ostergaard & Szkudlarek 2003). To image more subtle pathologies of the musculoskeletal system, other modalities are coming to prominence. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows good visualisation of soft-tissue structures such as ligaments, tendons and synovium. Methods such as T1- and T2-weighted sequences and STIR, particularly if enhanced with a contrast agent such as gadolinium-DTPA, allow for good differentiation of healthy and inflamed soft tissues, and identification of bony oedema and erosions (Bouysset et al 1995, Ostergaard & Szkudlarek 2003). Advances in imaging technology allow for sophisticated three-dimensional reconstructions that can be used to provide valuable visual and quantitative data on the severity of disease activity locally (Woodburn et al 2002a,c). MRI is expensive and time consuming, however, and cannot be considered a first resort. For high-resolution imaging of bony structures, computed tomography (CT) remains the modality of choice. However, CT requires exposure to ionising radiation and is unsuitable for screening or repeated use.

High-resolution ultrasound (HRUS) is becoming increasingly popular as a ‘bedside’ modality in rheumatology, as it is low risk, differentiates soft tissues structures well and involves no exposure to ionising radiation (Ostergaard & Szkudlarek 2003, Wakefield et al 2000). It is possible using HRUS, to reliably differentiate between inflamed and healthy soft tissues, identify erosions that are undetectable on a plain radiograph and also to investigate structures dynamically (Olivieri et al 1998, Ostergaard & Szkudlarek 2003, Szkudlarek et al 2003, Wakefield et al 2000). There are some limits to HRUS imaging where features of interest, such as those within larger joints such as the ankle, lie too deep to the surface to be imaged, or lie in the ultrasound shadow of structures that form a barrier to the imaging signal. More validation studies are needed, but HRUS imaging is an area of rapid development in musculoskeletal radiology and is proving of considerable clinical use (Riente et al 2006).

Management principles

In a dedicated rheumatology foot health service, callus reduction, footwear advice and provision, and orthosis prescription are mainstays of management. In a Bradford multidisciplinary rheumatology clinic, some 76% of patients required foot orthoses and 43% required replacement footwear (Helliwell 2003), while in a Rochdale audit the requirement (not the provision) for orthoses and footwear was estimated to be 60% and 10%, respectively. An audit of our Leeds clinic indicates that just over one-quarter of our patients are referred on for footwear intervention, with another quarter receiving orthoses. General foot care (nails, corns and callus) also accounts for one-third of our caseload, a figure lying between those reported separately by Williams & Bowden (2002) and Helliwell (2003), and illustrating the variability in caseloads between services.

Injectable steroid is useful in many cases for controlling local areas of inflammatory activity such as articular synovitis or tenosynovitis. Injection of corticosteroid has been shown to be effective in relieving plantar heel pain in the short term (Mulherin & Price 2009) and is used widely to control local sites of inflammation associated with inflammatory arthritis (Cardone & Tallia 2002, Crawford et al 1999). Local injection of corticosteroid now falls within the extended scope of practice of a number of allied health professionals and can be a valuable adjunct to traditional conservative therapies for pain in the foot. It is generally recommended that steroid injections are used sparingly because of the degenerative effects on tissues following repeated injection. Patients also need to rest the body part for 24–48 hours after injection because of the risk of local tissue damage while there are high concentrations of steroid present in the tissues and to limit dispersion of the agent (Cardone & Tallia 2002).

Traditionally, most injections of local corticosteroid have been administered ‘blind’, that is without the aid of radiographic imaging to direct the needle accurately to the desired point of deposition. Recently, the wider availability of ultrasound imaging in musculoskeletal practice has led to a move towards using ‘guided’ injections, where the agent can be delivered more accurately to the required site.

Provision of foot health services – current provision, multidisciplinary involvement, surgery

There is a clear gap between the need for foot health services generally and the provision of these services in the UK. Approximately 1 in 10 people with foot pain have nothing at all done about it, and a further 40% self-manage their painful foot problems (Gorter et al 2001). However, the fact that foot problems are substantially underreported (Gorter et al 2000, Munro & Steele 1998) makes services planning and evaluation difficult.

Only one-quarter of those needing foot health services have adequate access provided by NHS services (White & Mulley 1989) and 30–40% of people needing access to foot care services simply do not have services available to them from any source (Garrow et al 2004, Harvey et al 1997). The discrepancy is greater still in the rheumatology population, with a recent survey of 139 patients attending rheumatology outpatients at a North of England hospital finding that 89% of patients had foot problems. Sixty per cent of these patients had no access to foot care services on clinical examination (Williams & Bowden 2002). The inequity in foot health provision to patients with rheumatic disorders has been noted by rheumatologists and podiatrists alike (Helliwell 2003, Michelson et al 1994, Otter 2004).

Multidisciplinary care is important in managing rheumatology patients, and there are two sides to this. On the one hand, rheumatology patients are often complex medically, and it is essential that the practitioner managing the foot problems has a dialogue with, and good back up from, the patient’s rheumatology physician. Conversely, expertise in dealing with foot problems is often limited among rheumatologists, and a strong case can be made for better integration of foot health services into rheumatology (Korda & Balint 2004).

While multidisciplinary care is well established and of proven benefit in other disciplines such as diabetology, provision of multidisciplinary foot health services in rheumatology is highly variable. Multidisciplinary clinics will often cover the medical basics, education and coping strategies, but it is less common to find podiatry included as a core part of the team despite the level of need in this patient group nearing 80% (Prier et al 1997). We surveyed rheumatology departments in the UK and established that, while 85% of rheumatology departments include rheumatology specialist nurses in the team and 44% include physiotherapy, only 27.1% include podiatry (Redmond & Helliwell 2005). The provision of foot health services also varies widely geographically, ranging from 65% in Yorkshire and the North East; to 50% in London and the South East, to 25% and 33% in Scotland and Wales, respectively.

Only half the rheumatology departments in our survey reported having access to foot heath services for important functions such as nail care and corn/callus reduction. We have criticised the lack of coordination of foot services in rheumatology previously, noting the problems that are created with patient dissatisfaction, and impediment to the development of the service within the medical teams (Helliwell 2003). We have suggested, from local experience, that a multidisciplinary foot team should consist of at least a rheumatologist, a podiatrist and an orthotist, and it would be quite appropriate to extend team membership to orthopaedics and physiotherapy as resources permit. The Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA) and Podiatry Rheumatic Care Association (PRCA) Standards of Care (2008) provide a useful mechanism for evaluating musculoskeletal foot health services and planning strategically to best integrate medical and foot health teams. Succession planning is imperative, as small teams such as these can be highly dependent on individual people for their success, and it is all too easy for a successful service to run into problems if one of the team leaves and his or her replacement is unable to participate at the same level. To ensure a level of professional development appropriate to a specialist team it is advisable that arrangements are made for continuing professional development, and for update courses to be undertaken jointly with the rest of the rheumatology team (Otter 2004).

A good multidisciplinary rheumatology foot health service is likely to tap into considerable unmet need for foot health services (Prier et al 1997) and it is our and others’ experience that the service will expand rapidly and attract referrals for a range of conditions (Helliwell 2003, Prier et al 1997). A robust business plan should be devised prior to initiating a service in order to pre-empt these potential problems and to ensure the long-term success of such a venture. The initial business plan should also be supplemented with careful documentation of patient outcomes (Prier et al 1997) so that the merits of the service can be quantified and the cost effectiveness evaluated in the long term.

Within a rheumatology multidisciplinary team, rheumatology specialist nurses play an increasingly central role, responsible for administering, monitoring and modifying patients’ medication, education, and a valuable psychosocial support role (NICE 2009). The therapy professions, specifically physiotherapy and occupational therapy, are also important in the overall management of the symptoms associated with inflammatory arthritis, and NICE (2008, 2009) has produced explicit guidance on these roles in rheumatology. The main roles for rehabilitation therapies are to help people limit disability through skills training, exercise training, pain management, joint protection programmes, and provision of splints and orthoses (Steultjens et al 2004). The merit of providing splints as part of a regimen of occupational therapy has been demonstrated, and echoes the data for foot orthoses provided as part of podiatric management (Budiman-Mak et al 1995, Steultjens et al 2004, Woodburn et al 2002a).

Service provision

The foot health services that should be provided as part of a multidisciplinary foot health team in rheumatology fall into five categories.

Education and self-management advice

In an era of increased patient empowerment, education programmes have become more commonplace. Self-management is known to result in improved health status (Rao & Hootman 2004), but there is conflicting evidence over the merit of formal education programmes for patients with rheumatic disorders. Education is the mainstay of management in non-systemic conditions such as chronic mechanical low back pain, and provides demonstrable benefits over traditional medical management of this condition (Rao & Hootman 2004). In the inflammatory diseases the picture is less clear, however, and the measurable benefits are probably confined to short-term effects on the psychological factors and impact of disability (Riemsma et al 2004). Education in RA provides measurable improvement in knowledge but only small and non-significant changes in objective and health-related quality of life measures (Helliwell et al 1999). In OA, a small reduction in the use of healthcare services was reported after individualised education, but again no changes in patient outcomes have been found (Riemsma et al 2004, Ward 2000). Rheumatology patients can be overwhelmed with information at diagnosis, however, and it may be best to introduce education selectively, focusing on issues of particular relevance at any given time. This is equally true for foot health advice, and clear guidance on the provision of information has been provided in the ARMA/PRCA Standards of Care (2008).

General foot care, nail cutting, corn and callus reduction, provision of padding

Patients with musculoskeletal conditions have an increased need for a range of basic foot care services. Deformities of the foot associated with joint changes and soft-tissue lesions create areas of pressure that result in callus and corn formation. Arthritis in the hands may make foot care and hygiene tasks difficult, and spinal involvement can make bending to attend to basic foot care tasks impossible.

It is well accepted anecdotally and in simple cohort studies (Redmond et al 1999, Woodburn et al 2000) that debridement of symptomatic callosities and removal of cornified nuclei reduces pain in the short term. One randomised trial has provided contradictory evidence, however, suggesting that callus debridement was no better than placebo at reducing pain scores in patients with RA (Davys et al 2004). The study authors do not recommend abandoning callus debridement because the anecdotal evidence and patient demand is so overwhelming, but it is clear that more research is needed into this important area of podiatric practice. Offloading strategies are essential for managing the deformed rheumatic foot, and podiatrists can be useful in providing orthoses and/ or footwear (Korda & Balint 2004).

High-risk management of the vasculitic or ulcerative foot

This is a sometimes neglected aspect of rheumatology practice. Risk of ulceration is raised in a number of musculoskeletal diseases, such as RA, in which the point prevalence is about 3% (Firth et al 2008). Management of the high-risk foot accounts for approximately one-quarter of the Leeds foot health appointments, and in one report of the case profile of multisystem wound care service rheumatology patients made up 6% of the total caseload (Steed et al 1993). Prevention and management of the high-risk foot is an important part of the foot health service in rheumatology (Korda & Balint 2004) (Figure 8.3).

Extended scope practice and surgery

The advent of the extended scope practitioner (ESP) has created the opportunity for foot health services to be more responsive to patients’ needs. The new ESPs are able to access enhanced investigations and can intervene more proactively, making amendments to patients’ pharmacological management and using injectable steroids. More sophisticated surgical techniques and better integration of surgeons into the early management have also improved the surgical management of the foot in rheumatology.

SPECIFIC DISEASES

Seropositive inflammatory arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Definition

RA is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory disease with polyarthritis as its main feature. Chronic inflammation leads to joint damage and functional impairment (van Gestel et al 1996). Rheumatoid factors are detectable by serological testing in a large proportion of cases.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of RA in the population is approximately 7.7 per 1000 (0.8%), a risk that is doubled for relatives of confirmed cases (Hawker 1997). Approximately two-thirds of new cases arise in females, and mostly in the fourth and fifth decades of life, although there is wide variation and some suggestion that the age of onset is increasing. In one large UK cohort reported recently, the average age at onset was 55 years (Young et al 2000).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made according to diagnostic criteria defined by the American College of Rheumatology (Box 8.3). Key serological markers for the systemic inflammatory response are a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Testing for rheumatoid factor aids in diagnosis and estimating the prognosis (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002). Rheumatoid factor is present in 65–80% of patients with RA, and those who are rheumatoid factor positive are predisposed to more severe disease. Radiographic changes are often not present in early disease or on plain film. Radiography may not help with diagnosis, although it does provide a useful baseline for future assessment (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002). Enhanced visualisation of inflamed synovium is possible with modern HRUS, and this modality may be helpful in early cases.

Box 8.3 American College of Rheumatology 1987 criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis

Four or more of the following criteria must be present:

There is an important role for primary care practitioners in aiding with the early recognition of as yet undiagnosed inflammatory arthritis (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002). The foot is the first site of involvement in about 1 in 8 cases of RA, and some 20% of patients report foot pain before any other manifestation of the disease (O’Brien et al 1997).

A consensus-based referral recommendation for primary care practitioners (Emery et al 2002) states that inflammatory (rheumatoid) arthritis should be considered, and patients referred rapidly for a rheumatology opinion if they demonstrate:

Pathology

The underlying histopathology is of an immune-mediated synovitis caused by a faulty autoimmune response to proteins such as immunoglobulin G. The synovial membrane of the affected joint becomes hyperplastic, and infiltrated with inflammatory cells that promote secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (including TNFα) (Feldman & Maini 2008). The synovial membrane proliferates further, forming a pannus, which increasingly intrudes into the joint space (Choy & Panayi 2001). Cells in the pannus release enzymes that degrade cartilage and the connective tissue matrix (Choy & Panayi 2001). Erosion is more extensive around the margins of joints, because the articular cartilage affords some initial protection to the subchondral bone (Gold et al 1988).

Clinical course

The disability pathway for inflammatory arthritis and the specific factors affecting the clinical course in RA are summarised in Figure 8.1. Modifiers include endogenous factors that affect the underlying pathology, biopsychosocial factors and exogenous factors.

The presence of rheumatoid factor is a key marker for subsequent disease severity and is found in about 60% of new cases (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002, Young et al 2000). Modern antibody testing, including for anti-CCP antibodies, has further improved diagnostic specificity and prognostic prediction (van Venrooij et al 2008). Other important prognostic factors include HAQ score, delay in instigating therapy, smoking, and the presence of certain immunogenetic markers (Sanmarti et al 2003, Young et al 2000).

There appears to be some shortening of the lifespan because of the disease course itself and also because of the risks associated with therapies such as oral steroids and DMARDs (Hawker 1997). RA is associated with decreased ability to undertake both paid work, and unpaid work such as domestic duties (Backman et al 2004), and everyday activities of work and leisure take longer to perform (March & Lapsley 2001). Work disability increases with disease duration. Approximately 20% of people with RA report significant work disability within a year of diagnosis, one-third by 2 years and up to 60% within 10 years of onset (Barrett et al 2000). A third of people with RA will leave the workforce permanently within 3 years of diagnosis (Barrett et al 2000).

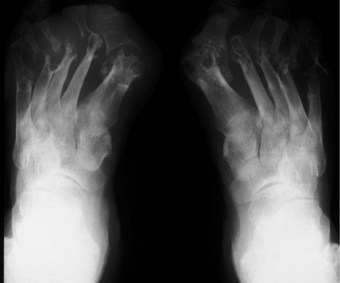

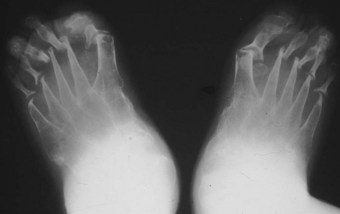

The clinical course of the disease improved markedly with improvements in DMARD therapy in the 1980s and 1990s, and more recently with the advent of biological immunotherapy. Patients treated with conventional DMARDs will typically do moderately well, with some 13% going into long-term remission, and just under one-half following a moderated disease course with episodes of remission and relapse (Young et al 2000). Patients following this disease course will do better than those untreated or on NSAIDs only, but joint degeneration does accrue in the long term (>10 years) and disability remains a factor in established RA (Gordon et al 2001). Joint-space narrowing occurs early in RA, and is initially symmetrical and uniform, although it becomes less regular as the joint degenerates (Kumar & Madewell 1987). Some ongoing joint degeneration will occur in all but the mildest or best-controlled cases, and joint replacement remains a mainstay of management in end-stage disease. Currently, some 1 in 10 people will require at least one joint replacement within 5 years of diagnosis (Young et al 2000), although it might be expected that this number will fall as early DMARD therapy starts to improve prognosis.

Medical management

The outline of medical management in rheumatology described in the earlier section of this chapter is derived primarily from the principles of management of RA and needs no repetition here. There are clear guidelines provided by the American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis (2002) and in the UK by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE 2009). An abridged schema adapted from the American College of Rheumatology guidelines for the medical management of RA can be seen in Figure 8.2.

It should be noted that while this schema represents an ideal clinical pathway, complete remission is still unusual (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002), and some patients respond particularly poorly to specific DMARDs, even to new biological agents (Feldmann 2002). Where full remission is not achieved, the management goals become symptom relief and maximisation of quality of life (American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis 2002). Medical treatment should thus be undertaken within a multidisciplinary setting, with other disciplines providing valuable input to the chronic disease process (NICE 2009).

The foot in rheumatoid arthritis

The prevalence and impact of foot problems is strongly related to disease duration (Michelson et al 1994) and the foot is eventually affected in nearly all people with RA, usually in a symmetrical pattern. Joint pain and stiffness is the most common initial presentation, but a range of other features may also be found, including tenosynovitis, nodule formation and tarsal tunnel syndrome, reflecting the widespread soft-tissue involvement. Foot-related impact is a consequence of a combination of factors, including pain, inflammation and mechanics (Turner et al 2008), with involvement of the feet both contributing to (van der Leeden et al 2008a) and representing a marker for impaired mobility and functional capacity in RA (Wickman et al 2004). In about three-quarters of people with RA, the foot contributes to difficulty with walking, and the foot is the main or only cause of walking impairment in one-quarter (Kerry et al 1994).

Some 20–25% of all surgical operations for RA relate to manifestations of the disease in the feet (Hamalainen & Raunio 1997). Despite this high demand, the success of surgical interventions is only moderate. Fewer than 50% of patients undergoing forefoot surgery for RA report ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ outcomes. Indeed, 13% of patients undergoing foot surgery for inflammatory arthropathy require subsequent reoperation because of poor outcomes (Hamalainen & Raunio 1997).

Hindfoot

Retrocalcaneal bursitis is common in RA, and often coexists with inflammation of the Achilles tendon and long flexor and extensor tendon sheaths (Stiskal et al 1997). This in turn leads to the development of longitudinal tendon tears and structural degeneration, which in the long term can occasionally lead to complete rupture of the tendon, especially in high-load tendons such as the tendon of tibialis posterior (Bouysset et al 1995, Kumar & Madewell 1987). Tendinopathy is best imaged using HRUS or gadolinium-enhanced MRI (see earlier), which will show a greater frequency of involvement than the clinical examination (Bouysset et al 1995). Lesions were found in the posterior tibial tendons of 53/67 patients in one recent study (Bouysset et al 2003), but complete rupture of the tendon is uncommon, even in severely deformed feet (Jernberg et al 1999, Masterton et al 1995). Spurs can be found on the plantar surface of the calcaneus in about one-third of established RA cases, with a similar prevalence of posterior spurs at the insertion of the Achilles tendon, although posterior spurs tend to be smaller and are often asymptomatic (Bouysset et al 1989). The degree of soft-tissue involvement is largely dependent on the systemic disease activity, but local areas of severe inflammation may respond to infiltration of steroid into joints or soft tissues (McGuire 2003).

Ankle (talocrural) joint degeneration occurs relatively rarely in RA, and is confined to severe and late-stage disease (1 in 10 patients after 20 years). Ankle-joint change is almost always preceded by subtalar joint involvement (Belt et al 2001), and may therefore be a consequence of altered hindfoot alignment (Cimino & O’Malley 1999). Subtalar joint disease is suggested where there is pain on walking over uneven ground and swelling posterior to the medial malleolus or in the sinus tarsi (Bouysset et al 1995). The subtalar joint is affected in about a quarter of long-standing RA patients (Bouysset et al 1987) but rarely in early disease.

In the longer term, synovitis in the hindfoot joints leads to systematic changes in hindfoot structure and function (Woodburn et al 2002). The altered function, combined with the effect of load bearing and increased soft-tissue laxity, lead the hindfoot to function in a progressively more pronated position, with the heel becoming more inclined into valgus and the tibia more internally rotated (Bouysset et al 1987, Keenan et al 1991, Woodburn et al 2002b) (Figure 8.4).

Initially, the deformities are largely reducible, and the elastic response of the soft tissues allows for correction. Rigid functional orthoses have been shown to restore normal function at this early stage, and to slow the progression of fixed deformity (Woodburn et al 1999). If uncorrected, bony adaptation and disease-related changes in soft-tissue histology will lead to irreducible structural changes.

Varus deformities of the hindfoot occur in fewer than 1 in 30 people with RA (Kerry et al 1994, Vidigal et al 1975), and usually as a direct consequence of compensation strategies such as inversion of the forefoot to offload painful medial metatarsophalangeal joints (MTPJs).

It is important to note that health-related quality of life is better related to rearfoot pain than rearfoot deformity (Platto et al 1991), and so interventions should be provided on the basis of patient reports of impairment rather than reserved for those with the appearance of worse foot deformity.

In the valgus rheumatoid foot, synovitis and compression of tissues on the medial aspect of the hindfoot can lead to tarsal tunnel syndrome (Jernberg et al 1999). This manifests as a paraesthesia or as a burning sensation over the distribution of the tibial nerve on the plantar surface of the foot. Tarsal tunnel syndrome may respond to local injection of corticosteroid, but may require surgical decompression.

Surgical procedures most commonly performed on the rheumatoid hindfoot include tarsal tunnel decompression, and ankle, subtalar or talonavicular arthrodesis (McGuire 2003). There have been calls for surgical interventions to be considered earlier, as it is proposed that an early correction may improve local mechanics and minimise subsequent degeneration in neighbouring joints (Cimino & O’Malley 1999, Cracchiolo 1993). At present, however, most surgical interventions in the rheumatoid hindfoot are performed on feet in the late stages of disease.

Subtalar arthrodesis is often indicated following rupture of the tendon of tibialis posterior, where tendon repair is often not possible because of the degenerate nature of the tissue. In the absence of repair, the continued lack of medial stability leads to a poor prognosis unless the joint is fused surgically (Bouysset et al 1995). The salvage procedure for severe cases of hindfoot structural change is triple arthrodesis following corrective wedge osteotomies to restore better alignment (Cimino & O’Malley 1999). Ankle and hindfoot arthroplasty in RA is directed toward addressing the degenerative joint changes, and so these procedures are discussed more fully in the later section on OA.

In the presence of significant deformity, adaptive footwear might be necessary. The addition of external flanges to the heel, along with reinforcement of the heel counter and medial arch of the upper of the shoes can aid with hindfoot stability. Extra-depth shoes allow for an orthosis to be better accommodated.

Midfoot

The joints of the midfoot are affected widely, with the talonavicular joint and Lisfranc’s joints affected in 15–30% of cases (Bouysset et al 1987). Diffuse joint degeneration may occur, although the characteristic erosions seen in the forefoot (Figure 8.5) are generally less common in the rheumatoid midfoot.

Forefoot

The MTPJs are the joints most commonly affected in RA (Weinfeld & Schon 1998), and MTPJ involvement often precedes that of any other joints, again with a symmetrical distribution (Pensec et al 2004, Priolo et al 1997). Early synovitis can lead to swelling of the digits (Kumar & Madewell 1987), and MTPJ synovitis, which is noted clinically as a warm boggy feeling to the joint on palpation, can lead to separation of neighbouring toes (the so-called ‘daylight sign’).

In the longer term, the acute phase will reduce (van der Leeden et al 2008b) and the rheumatoid forefoot will develop a typical marked hallux-valgus-type presentation and hammer toe deformities of the lesser toes (Figure 8.6). The hallux valgus deformity of RA is severe, with a large medial eminence, and it often results in first MTPJ subluxation (Weinfeld & Schon 1998). The second, third and fourth toes will typically exhibit lateral drift in addition to the hammer toe deformity, while the fifth toe will often be directed toward the midline, coming to lie over or under the fourth toe. It is common for the lesser digits to cease weight bearing entirely, and in combination with anterior displacement and atrophy of the plantar fat pads this leads to significantly increased pressure under the MTPJs (Turner & Helliwel 2003), which in turn is associated with greater impairment (Schmiegel et al 2008). Prominent adventitious bursae develop under the metatarsal heads, and these are frequently overlaid with callus (Figure 8.7). Bursitis at this site will be painful, and localised areas of skin ulceration are not uncommon (Figure 8.8). Plantar pressure data show the areas of increased pressure to be highly localised, and patients often describe a feeling of ‘walking on pebbles’.

The pain from the forefoot, and to a lesser extent the midfoot and hindfoot joints leads to characteristic changes in the gait of people with RA. Gait velocity decreases, as both the cadence and stride length are reduced. The double-support period extends to minimise the forces applied to the foot, and a reluctance to load the forefoot leads to delay in loading and a change in the velocity of centre-of-pressure profile (Hamilton et al 2001, Keenan et al 1991, O’Connell et al 1998, Turner & Helliwel 2003).

The severity of the changes that occur in the rheumatoid forefoot can often lead to a requirement for non-standard footwear (Figure 8.9). Traditionally, prescription footwear was bespoke (i.e. shoes were made to an individual cast or model) and were intended to account for specific individual features. Long-standing dissatisfaction with this approach, due to the high costs and unacceptable levels of patient (and practitioner) satisfaction (Williams et al 2007) has seen a change in approach in more recent years (Herold & Palmer 1992, Lord & Foulston 1989). One recent Dutch study indicated that about one-third of RA patients had been provided with orthopaedic footwear and, in an encouraging trend, 80% of this was in daily use (de Boer et al 2009).

Accommodative footwear can be provided off-the-shelf if the requirement is simply for extra depth or soft uppers in the toe box. The patient’s own shoes may be adapted in some cases, or bespoke shoes may still be made. Off-the-shelf shoes have been shown to provide significant improvements in pain, quality of life and gait parameters (Fransen & Edmonds 1997, Williams et al 2007), and are especially effective when combined with semi-rigid orthoses (Egan et al 2003). There is evidence for similar levels of satisfaction with bespoke and off-the-shelf shoes for people with RA (Kerry et al 1994).

Prescription footwear is usually provided in the NHS by orthotists working to a consultant prescription, but commercial alternatives provide other avenues that are increasingly available. Patient compliance is often problematic, and there is increasing evidence for benefits associated with better consideration of patient choice in the design and provision of bespoke footwear (Williams et al 2007).

Soft, flexible uppers made of soft leathers or stretchable textile can be very helpful in reducing the pressure on deformed digits (Figure 8.10), and in accommodating the increased width of the rheumatoid forefoot. The material characteristics and the presence of seams also warrant extra consideration where there is a risk of ulceration secondary to impaired arterial supply or vasculitis. The increased pressure found under the rheumatoid forefoot is aided by the addition of cushioning, and this can be provided separately or incorporated into prescription footwear (Egan et al 2003, Hodge et al 1999).

Rigid or semi-rigid, functional orthoses are known to be effective in limiting the rate of hindfoot and forefoot deformity, and in redistributing load away from the forefoot (Budiman-Mak et al 1995, Redmond et al 2004, Woodburn et al 2003), and contrary to past anecdotal opinion are well tolerated by people with RA (Woodburn et al 2002a). This approach, combined with forefoot cushioning, is effective at reducing pressure and pain in the painful forefoot (Chalmers et al 2000, Hodge et al 1999, Redmond et al 2004) and improving basic gait parameters (Kavlak et al 2003).

When joint pain is severe, the demand for painful motion in the forefoot joints during walking can be reduced by the provision of shoes with a rocker sole (Figure 8.11). A rocker sole is a straightforward adaptation little used in podiatry generally, but which can be quite effective in patients with RA.

Figure 8.11 A shoe with a rocker sole. Note: The patient had cut the heel counter of the shoe away herself to reduce pressure and discomfort.

Patients with RA affecting their back and/or hands may experience difficulties with shoe fastenings. Advice can be given when people are purchasing shoes to minimise this problem. Standard laces can be changed for elastic laces in existing shoes, removing the need for the wearer to bend and tie them. Alternative fastenings such as Velcro or elastic should be considered when choosing or prescribing orthopaedic footwear.

Many people with forefoot involvement require surgery and, because the forefoot is more affected by RA, forefoot procedures are generally performed before the hindfoot is operated on. However, if there is severe concomitant hindfoot involvement, stabilisation of the hindfoot does take precedence (Cracchiolo 1993).

The surgical approach to the forefoot joints is normally via dorsal incisions, as scarring on the weight-bearing plantar surface of the foot can lead to painful callus formation later. Plantar incisions are used when the skin quality on the dorsum of the foot might lead to problems with healing. Because of the severity of the joint degeneration in RA, excision arthroplasty is a part of most procedures, and the metatarsal heads, the base of the phalanges, or both are usually excised. Different procedures are used for the first MTPJ and lesser MTPJs. First MTPJ procedures, such as Keller’s excision arthroplasty, joint arthrodesis and replacement arthrodeses, are described elsewhere and will not be detailed here. For a severe lesser toe deformity, such as seen in RA, there are many procedures available, with those described by authors such as Clayton, Kates and Fowler forming the mainstay of rheumatoid foot surgery through the latter half of the 20th century. All lesser MTPJs are usually operated on simultaneously, because more conservative approaches involving surgery on only one of the most affected joints tend to have poorer long-term results in people with RA (Hughes et al 1991). Metatarsal head resection provides significant reduction in pain and forefoot pressure (Bitzan et al 1997, Rosenberg et al 2000), although the postoperative function cannot be considered normal and results tend to worsen in the longer term (Toolan & Hansen 1998). Modern variations, including techniques involving interposition of the plantar plate and preservation of the metatarsal head, are gradually supplanting the more traditional approaches (Cracchiolo 1993).

Subcutaneous lesions

Subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules are thought to arise in about one-quarter of patients with RA, usually those who are rheumatoid-factor positive and who have more severe disease (Gilkes 1987). The fibrotic nodules are associated with subcutaneous vasculitis and subsequent fibrosis, and arise at points of high stress, such as the extensor surfaces of elbows or knees. One study detected histological signs of rheumatoid necrosis (nodules) in the forefeet of 65% of a sample of people with RA, although most were subclinical (Berger et al 2004). Clinically evident nodules are not common in the feet, but affected sites include the posterior aspect of the heel and the dorsum of the forefoot. Rarely, nodules may break down or cause ulceration of overlying skin. If rheumatoid nodules are causing problems with shoe fitting or weight bearing, they may require surgical excision.

Skin and nails

Patients with RA of long disease duration will develop significant skin atrophy, with the skin taking on a pale, translucent quality (Gilkes 1987). The nails may be thickened and ridged, but are not usually symptomatic. The involvement of the hand, and difficulties with bending over for people with RA, mean that many patients need help with general foot health tasks such as nail cutting and maintenance of foot hygiene.

Vasculitis

Although better disease control appears to be reducing the prevalence of RA-related vasculitis (Turesson & Matteson 2009), it is not uncommon for vasculitis and ulceration to affect the rheumatoid foot, especially in patients who are rheumatoid-factor positive or have other signs of severe disease such as rheumatoid nodules (Cawley 1987). Usually, the pedal pulses are unaffected and the vasculitis is localised, affecting only part of the foot. The most common vasculitis in RA is endarteritis obliterans, in which inflammation of the intimal layer of the small blood vessels leads to occlusion of blood flow (Cawley 1987). The clinical features of endarteritis obliterans are infarcts in the nail beds and/or toe pulps. These are initially red and uncomfortable, but often turn black and painless within a few days, although in some cases the infarct progresses to form an ulcer. A second form, necrotising vasculitis, is caused by vessel-wall destruction (Genta et al 2006). If necrotising vasculitis affects the venules, it leads to local exsanguinations under the skin (palpable purpura). Necrotising vasculitis affecting arterioles leads to larger areas of ulceration, usually on the dorsum of the foot and toes (Cawley 1987) (Figure 8.12). Vasculitis can affect the vasa nervorum, leading to peripheral sensory neuropathy in some people with RA.

The foot is at high risk of ulceration in people with RA (Genta et al 2006). The risk is elevated because of the tendency to vasculitis and the thinning of the skin, and also because of the deformity accompanying the disease, which leads to the development of areas of high pressure, both on the dorsal and on the plantar aspects of the foot (Firth et al 2008). These risk factors are also present in addition to the usual cardiovascular risk factors present in an older population. In the Leeds rheumatology foot health clinic some 15% of the patients have vascular/high-risk presentations, and they account for over a quarter of appointment slots.

The site of the ulcer will give clues as to the important underlying pathology; breakdown over obvious pressure sites, such as the dorsum of deformed interphalangeal joints, might be expected to respond well to offloading of pressure. Breakdowns on the dorsum of the foot and lower leg are more likely to be of predominantly vasculitic origin (Cawley 1987) and need multidisciplinary management, including review of antirheumatic medication and possible supplementary therapy with agents such as Iloprost (Kay & Nancarrow 1984). The vasculitis associated with RA is also reported to respond well to anti-TNF therapy (Olsen & Stein 2004).

The increased susceptibility of many rheumatology patients to infection has been discussed previously, and must be considered in the care of this group.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Definition

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is a heterogeneous group of inflammatory arthropathies indicated by the presence of an inflammatory arthropathy, with an onset at less than 16 years of age, affecting one or more joints for longer than 6 weeks.

Epidemiology

Around 12 000 children in the UK have juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and girls are almost three times more likely to be affected than boys (Arthritis Research Campaign 2002).

Classification

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis has undergone a number of different classifications in the last 20 years. Each new classification is based on emerging knowledge of the taxonomy, natural history and immunopathology of the condition. The latest classification was decided upon in Durban in 2000 and suggests seven classes for children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: systemic arthritis, oligoarthritis, polyarthritis (two classes depending on rheumatoid factor status), psoriatic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis and ‘undifferentiated’ (Petty et al 1991). Better information on treatment and prognosis will be forthcoming as further studies of these groups are published.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis is based on the exclusion of other provisional diagnoses, such as infection and trauma. The history is usually of a chronic idiopathic synovitis, with onset in a single joint, typically the knee, ankle, hip or wrist (oligoarticular onset). Blood tests are less helpful in diagnosis than in adult-onset arthritis, but can help the clinician to decide to which subgroup the patient belongs.

Pathology

The pathophysiology is specific to the subgroup, but is essentially that of a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory synovitis. The enthesis, however, is the primary site of inflammation in enthesitis-related arthritis and psoriatic arthritis (see the section on adult seronegative arthropathy later in this chapter). The inflammatory pathways are similar in children and adults, and so the driving cytokine in many of the groups is TNFα.

Clinical course

Onset is often before 4 years of age, and the clinical course is variable and dependent on the clinical subgroup. In a good proportion of cases of oligoarticular disease, the disease may remit spontaneously with no long-term joint damage. In the majority of cases of polyarticular arthritis, the disease will continue for many years, sometimes without remission throughout the lifespan. Many cases positive for rheumatoid factor go on to a clinical course similar to RA.

Medical management

The general principle is of support rather than cure, and management is aimed at limiting symptoms, maintaining function and minimising permanent changes. NSAIDs will be the initial intervention. Intra-articular steroids are often used in severe monoarticular or oligoarticular forms. Disease-modifying drugs are used in cases with a poor prognosis, which will include those in the polyarticular group, the juvenile RA group and the systemic onset group.

The principal drugs used are methotrexate, corticosteroids and biological drugs such as anti-TNFα (Olsen & Stein 2004).

The local management of the foot and legs in these children will complement these therapies, as in the adult. It is, however, important to note the differences between children and adults with arthritis. Children are naturally stoic and will get on with their life as long as the symptoms are tolerable. Consequently, they are also more prone to loading inflamed joints and have little sense of joint protection.

The foot in juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Polyarticular type

The foot, especially the hindfoot and ankle, is involved in some two-thirds of polyarticular cases (Hendry et al 2008). Involvement of centres of ossification can lead to alterations in the shape of the growing bones and may cause deformity and brachydactyly (Moll 1987). Pes planus or pes cavus deformities may develop, as can the hallux-valgus-type picture seen in adult RA (Chen 1996).

Enthesitis-related arthritis and psoriatic arthritis

As noted previously, this presentation mirrors that of the adult seronegative arthropathies. The joints most affected in the foot are the hindfoot and interphalangeal joints, and entheseal inflammation at the insertion of the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia is common. Spinal involvement is common as the disease progresses. Inflammation in the mid- and hindfoot joints may lead to subsequent ankylosis, a not infrequent end point in this subgroup.

Particular attention should be given to the feet in juvenile idiopathic arthritis, as deformity will occur quickly. Better therapies have improved prognosis generally, but foot involvement remains common (Hendry et al 2008). Children are usually very accepting of in-shoe orthoses, but these must be reviewed annually, and more frequently during growth spurts. Joint inflammation may cause overgrowth or undergrowth of the adjacent long bones, so a careful watch for limb-length discrepancy should be maintained.

Seronegative inflammatory arthritis:

Introduction – common features

The seronegative arthritides are again a diverse group of conditions with a number of common features. There is a known association with the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) B27, and some 90% of patients with seronegative arthropathy of various types test positive for this antigen. Clinically, there is frequent involvement of the spine (axial involvement) in the seronegative arthritides, and many will first present as back pain before differentiating later. The inflammatory process in the seronegative arthropathies is also associated with enthesopathy – inflammation at the insertion of ligaments or tendons (Olivieri et al 1998). The most common sites for enthesopathy in the foot are the posterior calcaneus at the insertion of the Achilles tendon, the plantar calcaneus (the plantar fascia and the short flexor muscles), the base of the fifth metatarsal and the forefoot (McGonagle et al 2002, Olivieri et al 1998). There may be localised swelling at superficial insertions such as that of the Achilles tendon (Figure 8.13), and swellings can be especially pronounced when the enthesopathy extends to involve local bursae. In the fingers and toes the enthesitis and synovitis can present with marked dactylitis or ‘sausage digits’ (Figure 8.14). More widespread inflammation can lead to noticeable general swelling in the foot.

On radiography there may be periarticular proliferation of periosteum and bone, usually whiskery or fluffy in character, which contrasts with the bony erosions seen in RA. New bone formation may also be seen at the entheses as a consequence of the inflammatory process. It is uncommon for the foot in the seronegative arthropathies to be associated with vasculitis (Cawley 1987).

Ankylosing spondylitis (inflammatory back pain)

Definition

Ankylosing spondylitis is a progressive seronegative spondyloarthropathy that affects the axial skeleton (the spine and surrounding structures) predominantly, but which also has peripheral features that can involve the foot.

Epidemiology

The incidence of AS is approximately 1%, with men affected by AS three times as frequently as women (Braun & Sieper 2007). The ankle is affected in one-quarter of people with AS, and the forefoot in about 10% (Moll 1987). The inflammatory spondyloarthropathies cause 1.4 million working days to be lost each year, costing the UK economy some £122 million.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the modified New York criteria of the presence of one of:

However, these criteria have been criticised for having limited sensitivity (van der Heijde 2004).

Pathology

The pathology is not well understood overall, but appears to be driven by enthesitis. The sacroiliac joints are the worst affected, and initial inflammation can give way to ossification of the joints. TNF appears important in the pathological process, and overexpression of TNF precipitates an ankylosing-spondylitis-type presentation in transgenic mice. Preliminary findings from treatment studies suggest that TNF blockade appears even more beneficial in people with ankylosing spondylitis than in those with RA (Marzo-Ortega et al 2001).

Clinical course

Ankylosing spondylitis tends to manifest itself initially as low back or buttock pain because of sacroiliitis. Peripheral symptoms (including those in the foot) occur early in the disease but become less problematic over time, leaving the spondyloarthropathy as the main feature of long-standing disease. Spinal curvature increases over time as the long-standing inflammatory process leads to ankylosis and bone formation. The clinical course is generally less severe than in RA, and some cases will remit spontaneously. One notable feature of ankylosing spondylitis is the presence of fatigue as a significant factor for patients (van der Heijde 2004).

Medical management

NSAIDs are the mainstay of medical management in ankylosing spondylitis, although DMARDs, such as sulfasalazine, are also beneficial for the peripheral arthritis (DeJesus & Tsuchiya 1999, Olivieri et al 1998). Anti-TNF drugs are now established as major symptom-modifying drugs in ankylosing spondylitis. In one study of patients who had already failed to respond to conventional DMARD therapy, TNFα blockade caused complete resolution of 86% of entheseal lesions and led to substantial improvement in pain and quality of life (Marzo-Ortega et al 2001). Even supposedly end-stage ‘fixed’ spinal kyphoses can show some restoration of function once the inflammatory process has been suppressed. The Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS) group have defined response criteria similar to those used for RA, which have allowed for better evaluation of therapies (Lukas et al 2009).

The foot in ankylosing spondylitis

About 20% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis will have enthesitis in the feet, although any involvement of the foot in ankylosing spondylitis is usually transient and tends not to progress to severe degenerative joint disease (Kumar & Madewell 1987, Olivieri et al 1998). Involvement of the enthesis of the plantar fascia is accompanied by soft-tissue oedema in most cases and also by bone oedema in many (McGonagle et al 2002). Retrocalcaneal bursitis occurs fairly frequently in ankylosing spondylitis (Moll 1987).

If the foot is involved more extensively, the presentation has much in common with the other seronegative arthropathies, and erosions, periosteal proliferation and, characteristically, joint ankylosis are all seen. Affected joints will be swollen and tender, and radiographic investigation reveals that initial periarticular erosion is followed by bony proliferation and bone spur formation (Kumar & Madewell 1987).

The management of ankylosing spondylitis in the foot centres on systemic disease control supplemented by local measures. Where isolated sites in the foot are symptomatic, local injection of corticosteroid may reduce inflammation, and padding or orthoses may provide mechanical relief. Achilles tendon insertional enthesitis in seronegative spondyloarthropathy can, unfortunately, be intractable, although there is promise of effective therapy with anti-TNF drugs (Olivieri et al 2007).

Psoriatic arthritis

Definition

The diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis is usually used to refer to an inflammatory arthropathy occurring in the presence of psoriasis and in the absence of rheumatoid factor. In practice, it is not always possible to be so precise about the definition, as the joint involvement may be variable, and in some cases may even pre-date the development of skin lesions. Spinal involvement is characteristic, but peripheral joint involvement may range from the widespread and severe arthritis seen in the form arthritis mutilans (Figure 8.15), to a relatively mild monoarthritis. One form of psoriatic arthritis follows a disease course almost indistinguishable from that of RA.

Epidemiology

Psoriasis of the skin or nails affects 2–3% of the population, with approximately 12% of dermatological cases developing arthritis. There is no association between joint involvement and type of psoriatic presentation in the skin. Psoriatic arthritis is the second most common inflammatory arthropathy after RA (Veale & FitzGerald 2002).

Diagnosis

There are no widely agreed diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis, and so diagnosis is based on clinical features and the often difficult exclusion of other inflammatory arthritides such as RA and ankylosing spondylitis (Brockbank & Gladman 2002). Serology is not as useful as in RA, because the association between inflammatory markers and disease activity is less clear (Brockbank & Gladman 2002). Recently, new classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis have been developed by a large international group, and it appears that these criteria may also function well as diagnostic criteria (Taylor et al 2006).

Pathology

The immunogenetics of skin psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are complex, and at present seem only marginally interrelated, although the cellular features of inflammatory cell infiltration and membrane hyperplasia show some similarities (Veale & FitzGerald 2002). The precise pathological pathway leading to psoriatic arthritis is not well understood, although it is known that the process relates to enthesitis as well as the synovitis seen in RA. TNFα is expressed at higher levels than normal, but the relative proportions of other cytokines in psoriatic synovium are different to those seen in RA (Veale & FitzGerald 2002).

Clinical course

The textbook presentation is of a unilateral dactylitis (a ‘sausage digit’), although in reality the initial presentations are diverse. Early axial involvement is found in 40% of people with psoriatic arthritis. Case reports have suggested a temporal association between the onset of psoriatic arthritis and joint trauma in some cases, mimicking the Köebner phenomenon seen in psoriatic skin (Veale & FitzGerald 2002). Distal interphalangeal joint involvement is characteristic, contrasting with the proximal interphalangeal joint presentation seen in RA (Brockbank & Gladman 2002). Metacarpal or metatarsal joints can be affected, and again it is most common for the early presentation to be asymmetrical (Gold et al 1988).

The presence of arthritis in four or more joints is a significant predictor of a worse prognosis (Brockbank & Gladman 2002).

If the disease follows the arthritis mutilans course, the digital deformities tend to occur in haphazard directions, contrasting with the classic lateral drift seen in RA (Gold et al 1988). Ankylosis of affected joints is common and results in rigid deformity. Alternatively, where erosions predominate, flail digits may develop (Brockbank & Gladman 2002).

Medical management

Medical management of psoriatic arthritis is often similar to that of RA, with methotrexate and other DMARDs proving effective in combination with NSAIDs and exercise (Brockbank & Gladman 2002, DeJesus & Tsuchiya 1999). Psoriatic arthritis has proven highly responsive to anti-TNFα therapy in recent trials (Olsen & Stein 2004), and etanercept and infliximab suppress both the joint disease and the skin presentations (Leonardi et al 2003). Local corticosteroid injection into affected joints or tendon sheaths may be helpful (Brockbank & Gladman 2002). Treatment recommendations have recently been published by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis, which provides guidance on effective treatments for the different disease manifestations (Ritchlin et al 2009).

The foot in psoriatic arthritis

The foot may show the changes typical of psoriatic skin disease, with erythematous patches on the extensor surfaces, or plantar hyperkeratosis or pustule formation on the plantar surfaces. Pitting, discoloration, hyperkeratosis and lysis of the nails may occur, and splinter haemorrhages may be found around the apices of the toes.

Psoriatic arthritis will often present initially in the interphalangeal and then the metatarsophalangeal joints of the feet or hands (Gold et al 1988), although other joints may be affected, sometimes in a single ray pattern (Brockbank & Gladman 2002, Kumar & Madewell 1987).

Inflammation at the entheses results in bony erosions, and on radiographic investigation non-marginal erosions are evident early, with subchondral bone involved soon afterwards (Kumar & Madewell 1987). Reactive new bone formation around affected joints is characteristic, leading to a fuzzy appearance on the radiograph. Endosteal sclerosis will occasionally lead to a substantial increase in density of the shaft, the so-called ‘ivory phalanx’. The highly erosive pathology leads to a whittling of the joint margins and an unusual ‘pencil in cup’ appearance in advanced cases, where the distal end of the affected phalanx is cupped within an excessively concave surface at the proximal end of the more distal phalanx (Gold et al 1988, Kumar & Madewell 1987). Conversely, bony ankylosis can occur instead. Resorption of the distal phalanx occurs in about 5% of patients, resulting in a characteristic, pointed toe pulp (Gold et al 1988, Moll 1987).