CHAPTER 8 Disorders of Development

CHAPTER 8 Disorders of Development

DEVELOPMENTAL SURVEILLANCE AND SCREENING

Developmental and behavioral problems are more common than any category of problems in pediatrics except acute infections and trauma. Approximately 15% to 18% of children in the United States have developmental or behavioral disabilities. As many as 25% of children have serious psychosocial problems. Parents often neglect to mention these problems because they think the physician is uninterested or cannot help. It is necessary to monitor development and screen for the presence of such problems at health supervision visits, particularly in the preschool years, when the pediatrician may be the only professional to evaluate the child.

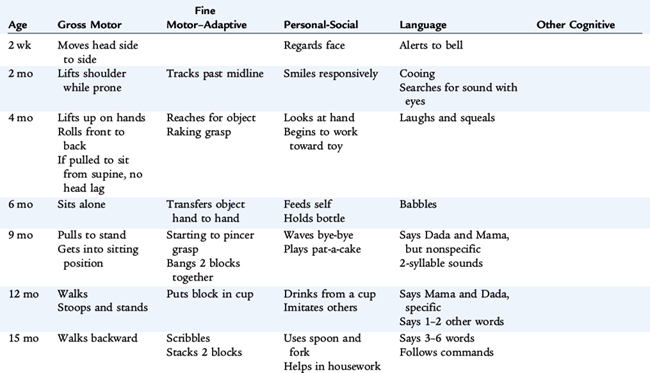

Development surveillance, done at every office visit, is an informal process comparing skill levels to lists of milestones. If suspicion of developmental or behavioral issues recurs, further evaluation is warranted (Table 8-1)

Developmental screening involves the use of standardized screening tests and a brief evaluation comparing the developmental skills of a particular child with a population of children to identify children who require further diagnostic assessment. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends the use of validated standardized screening tools at three of the health maintenance visits—9 months, 18 months, and 30 months. Clinics and offices that serve a higher risk patient population (children living in poverty) often perform a screening test at every health maintenance visit. A failed developmental screening test requires more comprehensive evaluation. Developmental evaluations for children with suspected delays and intervention services for children with diagnosed disabilities are available free to families. A combination of U.S. state and federal funds provide these services.

Screening tests can be categorized as general screening tests that cover all behavioral domains or as targeted screens that focus on one area of development. Some may be administered in the office by professionals, and others may be completed at home (or in a waiting room) by parents. Good developmental/behavioral screening instruments have sensitivity of 70% to 80% to detect suspected problems and specificity of 70% to 80% to detect normal development. Although 30% of children screened may be over-referred, this group also includes children whose skills are below average and who may benefit from definitive testing that may help address relative developmental deficits. The 20% to 30% of children who have disabilities that are not detected by the single administration of a screening instrument are likely to be identified on repeat screening at subsequent health maintenance visits.

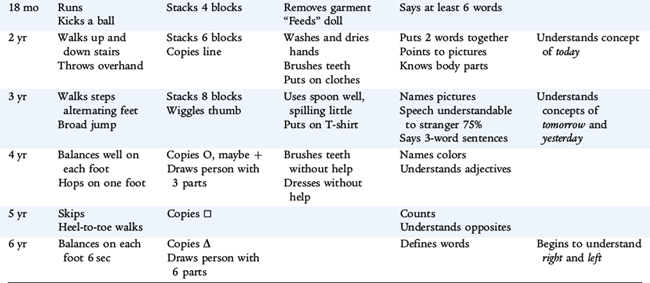

The Denver Developmental Screening Test II is commonly used by general pediatricians (Figs. 8-1 and 8-2). The Denver II assesses the development of children from birth to 6 years of age in four domains:

FIGURE 8-1 Scoring form for Denver II.

(From Frankenburg WK: Denver II Developmental Screening Test Training Manual, 2nd ed, Denver, Denver Developmental Materials, 1992.)

FIGURE 8-2 Instructions for the Denver II. Numbers are coded to scoring form (Fig. 8-1). “Abnormal” is defined as two or more delays (failure of an item passed by 90% at that age) in two or more categories or two or more delays in one category with one other category having one delay and an age line that does not intersect one item that is passed.

(From Frankenburg WK: Denver II Developmental Screening Test Training Manual, 2nd ed, Denver, Denver Developmental Materials, 1992.)

Items on the Denver II are carefully selected for their reliability and consistency of norms across subgroups and cultures. The Denver II is a useful screening instrument, but it cannot assess adequately the complexities of socioemotional development. Children with suspect or untestable scores must be followed carefully.

The pediatrician asks questions (items labeled with an “R” may be asked of parents to document the task “by report”) or directly observes behaviors. On the scoring sheet, a line is drawn at the child’s chronologic age. All tasks that are entirely to the left of the line that the child has not accomplished are considered delayed (at least 90% of the population accomplished the task). If the test instructions are not followed accurately or if items are omitted, the validity of the test becomes much poorer. To assist physicians in using the Denver II, the scoring sheet also features a table to document confounding behaviors, such as interest, fearfulness, or apparent short attention span. Repeat screening at subsequent health maintenance visits often detects abnormalities that a single screen was unable to detect.

Other developmental screening tools include parent-completed Ages and Stages Questionnaires, Child Development Inventories, and Parents’ Evaluations of Developmental Status. The last is a simple, 10-item questionnaire that parents complete between birth and 8 years. Parent-reported screens have good validity compared with office-based screening measures. In addition to these full screens, there may be a concern about only one area of development identified by parents or by an abnormal screen on the Denver II or other standardized screening tool.

Autism screening is recommended for all children at 18 and 24 months of age. Although there are several tools, many pediatricians use the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT). M-CHAT is an office-based questionnaire that asks parents about 23 typical behaviors, some of which are more predictive than others for autism or other pervasive developmental disorders. If the child demonstrates more than two predictive or three total behaviors, further assessment with an interview algorithm is indicated to distinguish normal variant behaviors from those children needing referral for definitive testing (see Chapter 20).

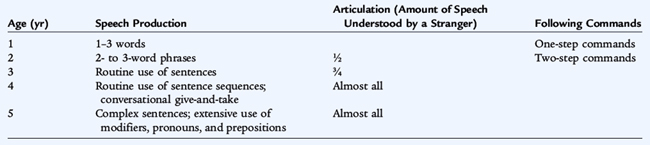

Language screening correlates best with cognitive development in the early years. Table 8-2 provides some rules of thumb for language development that focus on speech production (expressive language). Although expressive language (speech) is the most obvious language element, the most dramatic changes in language development in the first years involve recognition and understanding (receptive language).

Whenever there is a language delay, a hearing deficit must be considered. The implementation of universal newborn hearing screening detects many, if not most, of these children in the newborn period, and appropriate early intervention services may be provided. Conditions that present a high risk of an associated hearing deficit are listed in Table 8-3. Dysfluency (stuttering) is common in 3- and 4-year-olds. Unless the dysfluency is severe, is accompanied by tics or unusual posturing, or occurs after 4 years of age, parents should be counseled that it is normal and transient and to accept it calmly and patiently.

After the child’s sixth birthday and until adolescence, developmental assessment is initially done by inquiring about school performance (academic achievement and behavior). Inquiring about concerns raised by teachers or other adults who care for the child (after-school program counselor, coach, religious leader) is prudent. Formal developmental testing of these older children is beyond the scope of the primary care pediatrician. Nonetheless, the health care provider should be the coordinator of testing and evaluation performed by other specialists (e.g., psychologists, educational professionals).

OTHER ISSUES IN ASSESSING DEVELOPMENT AND BEHAVIOR

Ignorance of the environmental influences on child behavior may result in ineffective or inappropriate management (or both). Table 8-4 lists some contextual factors that should be considered in the etiology of a child’s behavioral or developmental problem.

TABLE 8-4 Context of Behavioral Problems

CHILD FACTORS

PARENTAL FACTORS

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS

Building rapport with the parents and the child is a prerequisite for obtaining the often-sensitive information that is essential for understanding a behavioral or developmental issue. Rapport usually can be established quickly if the parents sense that the clinician respects them and is genuinely interested in listening to their concerns. The clinician develops rapport with the child by engaging the child in developmentally appropriate conversation or play, providing toys while interviewing the parents, and being sensitive to the fears the child may have. Too often, the child is ignored until it is time for the physical examination. Similar to their parents, children feel more comfortable if they are greeted by name and involved in pleasant interactions before they are asked sensitive questions or threatened with examinations. Young children can be engaged in conversation on the parent’s lap, which provides security and places the child at the eye level of the examiner.

With adolescents, emphasis should be placed on building a physician-patient relationship that is distinct from the relationship with the parents. The parents should not be excluded; however, the adolescent should have the opportunity to express concerns to and ask questions of the physician in confidence. Two intertwined issues must be taken into consideration—consent and confidentiality. Although laws vary from state to state, in general, adolescents who are able to give informed consent (mature minors) may consent to visits and care related to high-risk behaviors (i.e., substance abuse; sexual health, including prevention, detection, and treatment of sexually transmitted infections; and pregnancy). Pediatricians should become familiar with the governing law in the state where they practice (see http://www.guttmacher.com/statecenter/updates/index.html). Most physicians who regularly work with adolescents believe that confidentiality is crucial to providing adolescents with optimal care (especially for obtaining a history of risk behaviors). States vary in the law governing confidentiality rights for adolescents, although most states support the physician who wishes the visit to be confidential. When assessing development and behavior, confidentiality can be achieved by meeting with the adolescent alone for at least part of each visit. However, parents must be informed when the clinician has significant concerns about the health and safety of the child. Often the clinician can convince the adolescent to inform the parents directly about a problem or can reach an agreement with the adolescent about how the parents will be informed by the physician.

EVALUATING DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL ISSUES

In an initial health supervision visit, the time to assess development is often short, and the assessment usually is only part of what needs to be accomplished during that office visit. Therefore, it may be best to explore developmental and behavioral problems during subsequent visits, when more comprehensive information and observations can be obtained. Responses to open-ended questions often provide clues to underlying, unstated problems and identify the appropriate direction for further, more directed questions. Histories about developmental and behavioral problems are often vague and confusing; to reconcile apparent contradictions, the interviewer frequently must request clarification, more detail, or mere repetition. By summarizing an understanding of the information at frequent intervals and by recapitulating at the close of the visit, the interviewer and patient and family can ensure that they understand each other.

If the clinician’s impression of the child differs markedly from the parent’s description, there may be a crucial parental concern or issue that has not yet been expressed either because it may be difficult to talk about (e.g., marital problems), because it is unconscious, or because the parent overlooks its relevance to the child’s behavior. Alternatively the physician’s observations may be atypical, even with multiple visits. The observations of teachers, relatives, and other regular caregivers may be crucial in sorting out this possibility. The parent also may have a distorted image of the child, rooted in parental psychopathology. A sensitive, supportive, and noncritical approach to the parent is crucial to appropriate intervention.