CHAPTER 30 Pediatric Undernutrition

CHAPTER 30 Pediatric Undernutrition

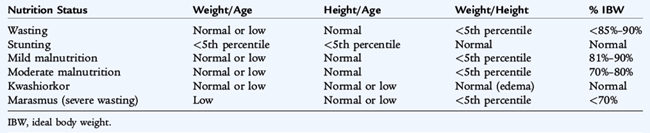

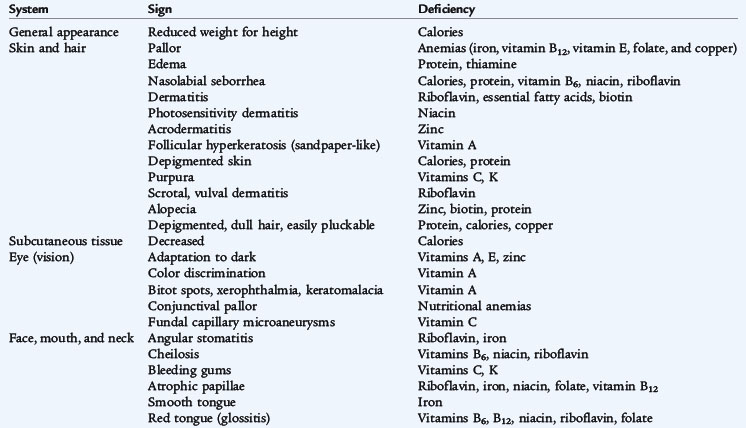

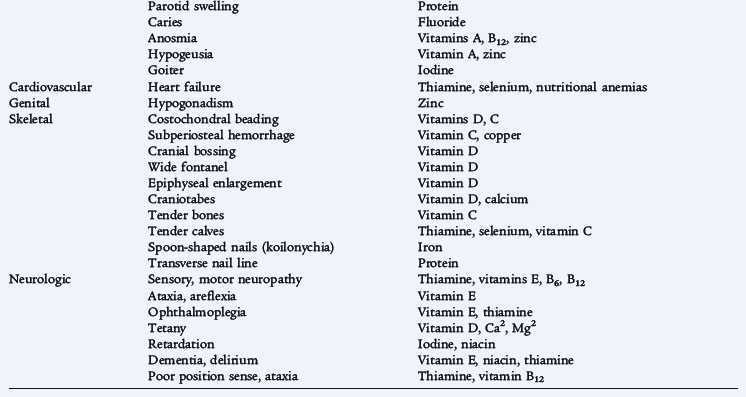

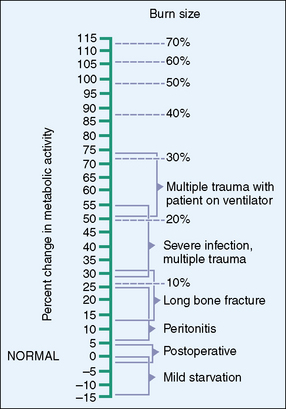

Worldwide, protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) is a leading cause of death in children younger than 5 years of age. PEM is a spectrum of conditions caused by varying levels of protein and calorie deficiencies. Primary PEM is caused by social or economic factors that result in a lack of food. Secondary PEM occurs in children with various conditions associated with increased caloric requirements (infection, trauma, cancer) (Fig. 30-1), increased caloric loss (malabsorption), reduced caloric intake (anorexia, cancer, oral intake restriction, social factors), or a combination of these three variables. See Table 30-1 for guidelines on the classification of pediatric undernutrition. Protein and calorie malnutrition may be associated with other nutrient deficiencies, which may be evident on the physical examination (Table 30-2).

Figure 30-1 Increased energy needs with stress.

(Adapted from Wilmore D: The metabolic management of the critically ill, New York, 1977, Plenum Publishing. Revised in Walker W, Watkins J, editors: Nutrition in pediatrics: basic science and clinical application. Boston, 1985, Little, Brown.)

FAILURE TO THRIVE

The most common diagnosis of pediatric undernutrition in the United States is often termed failure to thrive and is estimated to have a prevalence of 5% to 10% in young children (see Chapter 21). Psychosocial risk factors may develop as a result of medical problems or may be a primary cause of undernutrition. In the United States, most factors that contribute to poor growth are likely to be due to behavioral and psychosocial factors. The terms organic and nonorganic failure to thrive have lost favor in recognition of the frequent interplay between underlying medical conditions that may cause maladaptive behaviors. Similarly, social and behavioral factors that initially may have been associated with feeding problems and poor growth also may be associated with medical problems, including frequent minor acute illnesses.

MARASMUS

Marasmus is the term used for severe PEM and wasting (low wt/ht). Many secondary forms of marasmic PEM are associated with chronic diseases (cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis, cancer, acquired immunodeficiency virus, celiac disease). The principal clinical manifestation in a child with severe malnutrition is emaciation with a body weight less than 60% of the median (50th percentile) for age or less than 70% of the ideal weight for height and depleted body fat stores. Loss of muscle mass and subcutaneous fat stores are confirmed by inspection or palpation and quantified by anthropometric measurements. The head may appear large but generally is proportional to the body length. Edema usually is absent. The skin is dry and thin, and the hair may be thin, sparse, and easily pulled out. Marasmic children may be apathetic and weak. Bradycardia and hypothermia signify severe and life-threatening malnutrition. Atrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue is common, and monilial stomatitis is frequent. Inappropriate or inadequate weaning practices and chronic diarrhea are common findings in developing countries. Stunting (impaired linear growth (Table 30-1)) results from a combination of malnutrition, especially micronutrients, and recurrent infections. Stunting is more prevalent than wasting.

KWASHIORKOR

Kwashiorkor is hypoalbuminemic, edematous malnutrition and presents with pitting edema that starts in the lower extremities and ascends with increasing severity. It is classically described as being caused by inadequate protein intake in the presence of fair to good caloric intake. Other factors, such as acute infection, toxins, and possibly specific micronutrient or amino acid imbalances, are likely to contribute to the etiology. The major clinical manifestation of kwashiorkor is that the body weight of the child ranges from 60% to 80% of the expected weight for age; weight alone may not accurately reflect the nutritional status because of edema. Physical examination reveals a relative maintenance of subcutaneous adipose tissue and a marked atrophy of muscle mass. Edema varies from a minor pitting of the dorsum of the foot to generalized edema with involvement of the eyelids and scrotum. The hair is sparse; is easily plucked; and appears dull brown, red, or yellow-white. Nutritional repletion restores hair color, leaving a band of hair with altered pigmentation followed by a band with normal pigmentation (flag sign). Skin changes are common and range from hyperpigmented hyperkeratosis to an erythematous macular rash (pellagroid) on the trunk and extremities. In the most severe form of kwashiorkor, a superficial desquamation occurs over pressure surfaces (“flaky paint” rash). Angular cheilosis, atrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue, and monilial stomatitis are common. Enlarged parotid glands and facial edema result in moon facies; apathy and disinterest in eating are typical of kwashiorkor. Examination of the abdomen may reveal an enlarged, soft liver with an indefinite edge. Lymphatic tissue commonly is atrophic. Chest examination may reveal basilar rales. The abdomen is distended, and bowel sounds tend to be hypoactive.

TREATMENT OF MALNUTRITION

The basal metabolic rate and immediate nutrient needs decrease in cases of malnutrition. When nutrients are provided, the metabolic rate increases, stimulating anabolism and increasing nutrient requirements. The body of the malnourished child may have compensated for micronutrient deficiencies with lower metabolic and growth rates; refeeding may unmask these deficiencies. The gastrointestinal tract may not tolerate a rapid increase in intake. Nutritional rehabilitation should be initiated and advanced slowly to minimize these complications. Intravenous fluid should be avoided if possible to avoid excessive fluid and solute load and resultant heart or renal failure. If edema develops in the child during refeeding, caloric intake should be kept stable until the edema begins to resolve.

When nutritional rehabilitation is initiated, calories can be safely started at 20% above the child’s recent intake. If no estimate of the caloric intake is available, 50% to 75% of the normal energy requirement is safe. Following these guidelines should help avoid the refeeding syndrome, which is characterized by fluid retention, hypophosphatemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypokalemia. Careful monitoring of laboratory values and clinical status with severe malnutrition is essential.

When nutritional rehabilitation has begun, caloric intake can be increased 10% to 20% per day, monitoring for electrolyte imbalances, poor cardiac function, edema, or feeding intolerance. If any of these occurs, further caloric increases are not made until the child’s status stabilizes. Caloric intake is increased until appropriate regrowth or catch-up growth is initiated. Catch-up growth refers to gaining weight at greater than 50th percentile for age and may require 150% or more of the recommended calories for an age-matched, well-nourished child. A general rule of thumb for infants and children up to 3 years of age is to provide 100 to 120 kcal/kg based on ideal weight for height. Protein needs also are increased as anabolism begins and are provided in proportion to the caloric intake. Vitamin and mineral intake in excess of the daily recommended intake is provided to account for the increased requirements; this is frequently accomplished by giving an age-appropriate daily multiple vitamin, with other individual micronutrient supplements as warranted by history, physical examination, or laboratory studies. Iron supplements are not recommended during the acute rehabilitation phase, especially for children with kwashiorkor, for whom ferritin levels are often high. Additional iron may pose an oxidative stress; iron supplementation is associated with higher morbidity and mortality.

In most cases, cow’s milk–based formulas are tolerated and provide an appropriate mix of nutrients. Other easily digested foods, appropriate for the age, also may be introduced slowly. If feeding intolerance occurs, lactose-free or semielemental formulas should be considered.

COMPLICATIONS OF MALNUTRITION

Malnourished children are more susceptible to infection, especially sepsis, pneumonia, and gastroenteritis. Hypoglycemia is common after periods of severe fasting but also may be a sign of sepsis. Hypothermia may signify infection or, with bradycardia, may signify a decreased metabolic rate to conserve energy. Bradycardia and poor cardiac output predispose the malnourished child to heart failure, which is exacerbated by acute fluid or solute loads. Micronutrient deficiencies also can complicate malnutrition. Vitamin A and zinc deficiencies are common in the developing world and are an important cause of altered immune response and increased morbidity and mortality. Depending on the age at onset and the duration of the malnutrition, malnourished children may have permanent growth stunting (from malnutrition in utero, infancy, or adolescence) and delayed development (from malnutrition in infancy or adolescence). Environmental (social) deprivation may interact with the effects of the malnutrition to impair further development and cognitive function.