CHAPTER 45 Poisoning

CHAPTER 45 Poisoning

ETIOLOGY

The most common agents ingested by young children include cosmetics, personal hair products, cleaning solutions, and analgesics. The most common poisonings that lead to hospitalization involve acetaminophen, lead, and antidepressant medications. Fatal childhood poisonings are commonly caused by carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, medications (analgesics, iron, cardiovascular drugs, cyclic antidepressants), drugs of abuse, and caustic ingestions.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Poisoning and ingestions account for more than 130,000 visits to emergency departments and approximately 1% of all pediatric hospitalizations each year. Unintentional ingestions are most common in the 1- to 5-year-old age group. In older children, drug overdoses (poisonings) most often are associated with suicide attempts. Most ingestions are unintentional (83%), occur in the home (90%), and result in no toxicity (72%) or minor toxicity (15%). Only 0.1% of cases are fatal.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Unless the ingested drug is revealed, poisoning is often a diagnosis of exclusion. A comatose child should be considered to have ingested a poison until proven otherwise. The history and physical examination by someone who understands the signs and symptoms of various ingestions often provide sufficient clues to distinguish between toxic ingestion and organic disease (Table 45-1). Determination of all substances that the child was exposed to, type of medication, amount of medication, and time of exposure is crucial in directing interventions. Available data often are incomplete or inaccurate, requiring a careful physical examination and laboratory approach. A complete physical examination, including vital signs, is necessary. Certain complexes of symptoms and signs are relatively specific to a given class of drugs (toxidrome) (Table 45-2).

TABLE 45-1 Historical and Physical Findings in Poisoning

| ODOR | |

| Bitter almonds | Cyanide |

| Acetone | Isopropyl alcohol, methanol, paraldehyde, salicylate |

| Alcohol | Ethanol |

| Wintergreen | Methyl salicylate |

| Garlic | Arsenic, thallium, organophosphates |

| Violets | Turpentine |

| OCULAR SIGNS | |

| Miosis | Narcotics (except meperidine), organophosphates, muscarinic mushrooms, clonidine, phenothiazines, chloral hydrate, barbiturates (late), PCP |

| Mydriasis | Atropine, alcohol, cocaine, amphetamines, antihistamines, cyclic antidepressants, cyanide, carbon monoxide |

| Nystagmus | Phenytoin, barbiturates, ethanol, carbon monoxide |

| Lacrimation | Organophosphates, irritant gas or vapors |

| Retinal hyperemia | Methanol |

| Poor vision | Methanol, botulism, carbon monoxide |

| CUTANEOUS SIGNS | |

| Needle tracks | Heroin, PCP, amphetamine |

| Bullae | Carbon monoxide, barbiturates |

| Dry, hot skin | Anticholinergic agents, botulism |

| Diaphoresis | Organophosphates, nitrates, muscarinic mushrooms, aspirin, cocaine |

| Alopecia | Thallium, arsenic, lead, mercury |

| Erythema | Boric acid, mercury, cyanide, anticholinergics |

| ORAL SIGNS | |

| Salivation | Organophosphates, salicylate, corrosives, strychnine |

| Dry mouth | Amphetamine, anticholinergics, antihistamine |

| Burns | Corrosives, oxalate-containing plants |

| Gum lines | Lead, mercury, arsenic |

| Dysphagia | Corrosives, botulism |

| INTESTINAL SIGNS | |

| Cramps | Arsenic, lead, thallium, organophosphates |

| Diarrhea | Antimicrobials, arsenic, iron, boric acid |

| Constipation | Lead, narcotics, botulism |

| Hematemesis | Aminophylline, corrosives, iron, salicylates |

| CARDIAC SIGNS | |

| Tachycardia | Atropine, aspirin, amphetamine, cocaine, cyclic antidepressants, theophylline |

| Bradycardia | Digitalis, narcotics, mushrooms, clonidine, organophosphates, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers |

| Hypertension | Amphetamine, LSD, cocaine, PCP |

| Hypotension | Phenothiazines, barbiturates, cyclic antidepressants, iron, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers |

| RESPIRATORY SIGNS | |

| Depressed respiration | Alcohol, narcotics, barbiturates |

| Increased respiration | Amphetamines, aspirin, ethylene glycol, carbon monoxide, cyanide |

| Pulmonary edema | Hydrocarbons, heroin, organophosphates, aspirin |

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM SIGNS | |

| Ataxia | Alcohol, antidepressants, barbiturates, anticholinergics, phenytoin, narcotics |

| Coma | Sedatives, narcotics, barbiturates, PCP, organophosphates, salicylate, cyanide, carbon monoxide, cyclic antidepressants, lead |

| Hyperpyrexia | Anticholinergics, quinine, salicylates, LSD, phenothiazines, amphetamine, cocaine |

| Muscle fasciculation | Organophosphates, theophylline |

| Muscle rigidity | Cyclic antidepressants, PCP, phenothiazines, haloperidol |

| Paresthesia | Cocaine, camphor, PCP, MSG |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Lead, arsenic, mercury, organophosphates |

| Altered behavior | LSD, PCP, amphetamines, cocaine, alcohol, anticholinergics, camphor |

LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MSG, monosodium glutamate; PCP, phencyclidine.

| Agent | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | Nausea, vomiting, pallor, delayed jaundice–hepatic failure (72–96 hr) |

| Amphetamine, cocaine, and sympathomimetics | Tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, psychosis and paranoia, seizures, mydriasis, diaphoresis, piloerection, aggressive behavior |

| Anticholinergics | Mania, delirium, fever, red dry skin, dry mouth, tachycardia, mydriasis, urinary retention |

| Carbon monoxide | Headache, dizziness, coma, skin bullae, other systems affected |

| Cyanide | Coma, convulsions, hyperpnea, bitter almond odor |

| Ethylene glycol (antifreeze) | Metabolic acidosis, hyperosmolarity, hypocalcemia, oxalate crystalluria |

| Iron | Vomiting (bloody), diarrhea, hypotension, hepatic failure, leukocytosis, hyperglycemia, radiopaque pills on KUB, late intestinal stricture, Yersinia sepsis |

| Narcotics | Coma, respiratory depression, hypotension, pinpoint pupils, hyporeflexia |

| Cholinergics (organophosphates, nicotine) | Miosis, salivation, urination, diaphoresis, lacrimation, bronchospasm (bronchorrhea), muscle weakness and fasciculations, emesis, defecation, coma, confusion, pulmonary edema, bradycardia, reduced erythrocyte and serum cholinesterase, late peripheral neuropathy |

| Phenothiazines | Tachycardia, hypotension, muscle rigidity, coma, ataxia, oculogyric crisis, miosis, radiopaque pills on KUB |

| Salicylates | Tachypnea, fever, lethargy, coma, vomiting, diaphoresis, alkalosis (early), acidosis (late) |

| Cyclic antidepressants | Coma, convulsions, mydriasis, hyperreflexia, arrhythmia (prolonged Q-T interval), cardiac arrest, shock |

KUB, kidney-ureter-bladder radiograph.

COMPLICATIONS

A poisoned child can exhibit any one of six basic clinical patterns: coma, toxicity, metabolic acidosis, heart rhythm aberrations, gastrointestinal symptoms, and seizures.

Coma

Coma is perhaps the most striking symptom of a poison ingestion, but it also may be seen as a result of trauma, a cerebrovascular accident, asphyxia, or meningitis. A careful history and clinical examination are needed to distinguish among these alternatives.

Systemic and Pulmonary Toxicity

Hydrocarbon ingestion occasionally may result in systemic toxicity, but more often it leads to pulmonary toxicity. Hydrocarbons with low viscosity, low surface tension, and high volatility pose the greatest risk of producing aspiration pneumonia; however, when swallowed, they pose no risk unless emesis is induced. Emesis or lavage should not be initiated in a child who has ingested volatile hydrocarbons.

Caustic ingestions may cause dysphagia, epigastric pain, oral mucosal burns, and low-grade fever. Patients with esophageal lesions may have no oral burns or may have significant signs and symptoms. Treatment depends on the agent ingested and the presence or absence of esophageal injury. Alkali agents may be solid, granular, or liquid. Liquid agents are tasteless and produce full-thickness liquefaction necrosis of the esophagus or oropharynx. When the esophageal lesions heal, strictures form. Ingestion of these agents also creates a long-term risk of esophageal carcinoma. Treatment includes antibiotics if there are signs of infection and dilation of late-forming (2 to 3 weeks later) strictures.

Ingested button batteries also may produce a caustic mucosal injury. Batteries that remain in the esophagus may cause esophageal burns and erosion and should be removed with an endoscope. Acid agents can injure the lungs (with hydrochloric acid fumes), oral mucosa, esophagus, and stomach. Because acids taste sour, children usually stop drinking the solution, limiting the injury. Acids produce a coagulation necrosis, which limits the chemical from penetrating into deeper layers of the mucosa and damages tissue less severely than alkali. The signs, symptoms, and therapeutic measures are similar to those for alkali ingestion.

Metabolic Acidosis

A poisoned child may also have a high anion gap metabolic acidosis (mnemonic MUDPIES) (Table 45-3), which is assessed easily by measuring arterial blood gases, serum electrolyte levels, and urine pH. An osmolar gap, if present, strongly suggests the presence of an unmeasured component, such as methanol or ethylene glycol. These ingestions require thorough assessment and prompt intervention.

TABLE 45-3 Screening Laboratory Clues in Toxicologic Diagnosis

METABOLIC ACIDOSIS (MNEMONIC = MUDPIES)

Methanol,* carbon monoxide

Uremia*

Diabetes mellitus*

Paraldehyde,* phenformin

Isoniazid, iron

Salicylates, starvation, seizures

HYPOGLYCEMIA

Ethanol

Isoniazid

Insulin

Propranolol

Oral hypoglycemic agents

HYPERGLYCEMIA

Salicylates

Isoniazid

Iron

Phenothiazines

Sympathomimetics

HYPOCALCEMIA

Oxalate

Ethylene glycol

Fluoride

RADIOPAQUE SUBSTANCE ON KUB (MNEMONIC = CHIPPED)

Chloral hydrate, calcium carbonate

Heavy metals (lead, zinc, barium, arsenic, lithium, bismuth as in Pepto-Bismol)

Iron

Phenothiazines

Play-Doh, potassium chloride

Enteric-coated pills

Dental amalgam

KUB, kidney-ureter-bladder radiograph.

Dysrhythmias

Dysrhythmias may be prominent signs of a variety of toxic ingestions, although ventricular arrhythmias are rare. Prolonged Q-T intervals may suggest phenothiazine or antihistamine ingestion, and widened QRS complexes are seen with ingestions of cyclic antidepressants and quinidine. Because many drug and chemical overdoses may lead to sinus tachycardia, this is not a useful or discriminating sign; however, sinus bradycardia suggests digoxin, cyanide, a cholinergic agent, or β-blocker ingestion (Table 45-4).

TABLE 45-4 Drugs Associated with Major Modes of Presentation

COMMON TOXIC CAUSES OF CARDIAC ARRHYTHMIA

Amphetamine

Antiarrhythmics

Anticholinergics

Antihistamines

Arsenic

Carbon monoxide

Chloral hydrate

Cocaine

Cyanide

Cyclic antidepressants

Digitalis

Freon

Phenothiazines

Physostigmine

Propranolol

Quinine, quinidine

Theophylline

CAUSES OF COMA

Alcohol

Anticholinergics

Antihistamines

Barbiturates

Carbon monoxide

Clonidine

Cyanide

Cyclic antidepressants

Hypoglycemic agents

Lead

Lithium

Methemoglobinemia*

Methyldopa

Narcotics

Phencyclidine

Phenothiazines

Salicylates

COMMON AGENTS CAUSING SEIZURES (MNEMONIC = CAPS)

Camphor

Carbamazepine

Carbon monoxide

Cocaine

Cyanide

Aminophylline

Amphetamine

Anticholinergics

Antidepressants (cyclic)

Pb (lead) (also lithium)

Pesticide (organophosphate)

Phencyclidine

Phenol

Phenothiazines

Propoxyphene

Salicylates

Strychnine

* Causes of methemoglobinemia: amyl nitrite, aniline dyes, benzocaine, bismuth subnitrate, dapsone, primaquine, quinones, spinach, sulfonamides.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

Laboratory studies helpful in initial management include specific toxin-drug assays; measurement of arterial blood gases and electrolytes, osmoles, and glucose; and calculation of the anion or osmolar gap. A full 12-lead electrocardiogram should be part of the initial evaluation in all patients suspected of ingesting toxic substances. Urine screens for drugs of abuse or to confirm suspected ingestion of medications in the home may be revealing.

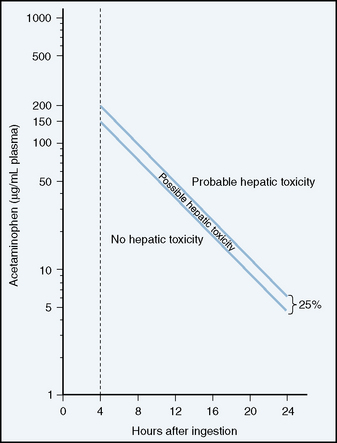

Quantitative toxicology assays are important for some agents (Table 45-5), not only for identifying the specific drug, but also for providing guidance for therapy, anticipating complications, and estimating the prognosis. The timing of measurement of the plasma level relative to the time of the patient’s ingestion of the drug also is useful in predicting the severity of illness for acetaminophen (Fig. 45-1). Patients with drug levels (related to the time after ingestion) in the serious zone require immediate treatment.

TABLE 45-5 Drugs Amenable to Therapeutic Monitoring for Drug Toxicity

ANTIBIOTICS

Aminoglycosides—gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin

Chloramphenicol

Vancomycin

IMMUNOSUPPRESSION

Methotrexate

Cyclosporine

ANTIPYRETICS

Acetaminophen

Salicylate

OTHER

Digoxin

Lithium

Theophylline

Anticonvulsant drugs

Serotonin uptake inhibitor agent

FIGURE 45-1 Semilogarithmic plot of plasma acetaminophen levels versus time. Rumack-Matthews nomogram for acetaminophen poisoning. Cautions for use of this chart are as follows: (1) The time coordinates refer to time of ingestion; (2) serum levels drawn before 4 hours may not represent peak levels; (3) the graph should be used only in relation to a single, acute ingestion; and (4) the lower solid line, 25% below the standard nomogram, is included to allow for possible errors in acetaminophen plasma assays and estimated time from ingestion of an overdose.

(Adapted from Rumack BH, Matthew H: Acetaminophen poisoning and toxicity. Pediatrics 55:871–876, 1975.)

TREATMENT

Supportive Care

Prompt attention must be given to protecting and maintaining the airway, establishing effective breathing, and supporting the circulation. This management sequence takes precedence over other diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. If the level of consciousness is depressed, and a toxic substance is suspected, glucose (1 g/kg intravenously), 100% oxygen, and naloxone should be administered.

Gastrointestinal Decontamination

The intent of gastrointestinal decontamination is to prevent the absorption of a potentially toxic ingested substance and, in theory, to prevent the poisoning. There has been great controversy about which methods are the safest and most efficacious. In light of this controversy, the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (AACT) and the European Association of Poison Centres and Clinical Toxicologists (EAPCCT) have written several position papers on the subject. Their most recent recommendations (2004) follow. Syrup of ipecac should not be administered routinely to poisoned patients because of potential complications and lack of evidence that it improves outcome. Likewise, gastric lavage should not be used routinely, if ever, in the management of poisoned patients because of lack of efficacy and potential complications. Single-dose activated charcoal decreases drug absorption when used within 1 hour of ingestion; however, it has not been shown to improve outcome. Thus, it should be used selectively in the management of a poisoned patient. Charcoal is ineffective against caustic or corrosive agents, hydrocarbons, heavy metals (arsenic, lead, mercury, iron, lithium), glycols, and water-insoluble compounds. Multiple-dose activated charcoal should be considered only if a patient has ingested a life-threatening amount of carbamazepine, dapsone, phenobarbital, quinine, or theophylline.

Also, the administration of a cathartic (sorbitol or magnesium citrate) alone has no role in the management of the poisoned patient. The AACT has stated that based on available data, the use of a cathartic in combination with activated charcoal is not recommended.

In addition, whole bowel irrigation using polyethylene glycol (GoLYTELY) as a nonabsorbable cathartic may be effective for toxic ingestion of sustained-release or enteric-coated drugs. The AACT does not recommend the routine use of whole bowel irrigation. However, there is theoretical benefit in its use for potentially toxic ingestions of iron, lead, zinc, or packets of illicit drugs.

Additional Therapy

After initial resuscitation and gastrointestinal decontamination (if indicated) have been achieved, determining whether further therapy is needed is often difficult. There are three basic choices in the subsequent care of a child with a significant ingestion:

To make a rational decision regarding these options, a judgment should be made as to whether the drug causes tissue damage (e.g., methyl alcohol, aspirin, acetaminophen, theophylline, iron, ethylene glycol). Tissue damage is defined as an irreversible or slowly reversible structural or functional change in an organ system as a direct result of ingestion of a poison; this definition precludes indirect effects, such as respiratory depression or hypotension.

The decision about further therapy should take into consideration the amount of poison ingested; the diagnostic assessment, including the condition of the patient at the time of presentation; and the natural history of the suspected type of ingestion. All of these variables may be influenced by the child’s prior clinical status or underlying medical problems (e.g., underlying hepatic or renal impairment). In the presence of a chronic ingestion, an acute overdose may cause significant clinical toxicity with a lower dose of the drug.

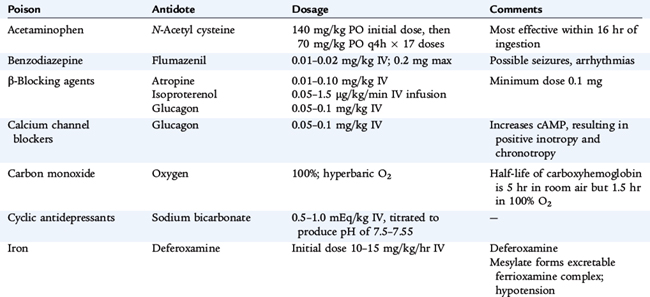

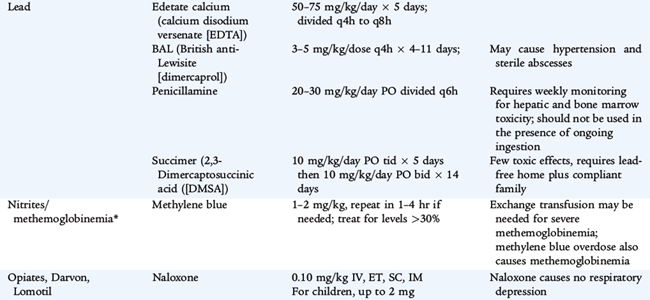

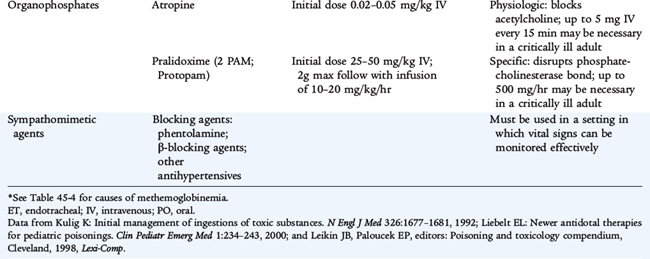

For most common ingestions in healthy individuals, continued supportive care and treatment directed toward specific complications are appropriate. Specific antidotes should be used according to prescribed guidelines (see Table 45-6). Active removal (hemoperfusion or dialysis) should be undertaken only for toxins that may cause tissue damage, for toxins that have been ingested by a patient already exhibiting confounding medical problems or to avoid prolonged supportive care. When in doubt, contacting one of the U.S. Poison Control Centers (1-800-222-1222) can help determine what additional treatment is necessary.

PROGNOSIS

Mortality from poisoning is rare. The most common exposures resulting in death include carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, and opioids (all of which interfere with oxygen delivery to tissues). Medications that affect cardiac function (calcium channel antagonists, β-adrenergic sustained-release medications, tricyclic antidepressants, and adrenergic ingestions) also are in the top 10 causes of death from poisoning.