CHAPTER 124 Tuberculosis

CHAPTER 124 Tuberculosis

ETIOLOGY

The agent of human tuberculosis is Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The tubercle bacilli are pleomorphic, weakly gram-positive curved rods 2 to 4 μm long. Mycobacteria are acid fast, which is the capacity to form stable mycolate complexes with arylmethane dyes. The term acid-fast bacilli is practically synonymous with mycobacteria. Mycobacteria grow slowly and culture from clinical specimens on solid synthetic media usually takes 3 to 6 weeks. Drug-susceptibility testing requires an additional 4 weeks. Growth can be detected in 1 to 3 weeks in selective liquid media using radiolabeled nutrients. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of clinical specimens allows rapid diagnosis in many laboratories.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Susceptibility to infection with M. tuberculosis disease depends on the likelihood of exposure to an individual with infectious tuberculosis and the ability of the person's immune system to control the initial infection and keep it latent. An estimated 10 to 15 million persons in the United States have latent tuberculosis infection. Without treatment, tuberculosis disease develops in 5% to 10% of immunologically normal adults with tuberculosis infection at some time during their lives. An estimated 8 million new cases of tuberculosis occur each year among adults worldwide, and 3 million deaths are attributed to the disease annually. In developing countries, 1.3 million new cases of the disease occur in children under 15 years of age, and 450,000 children die each year of tuberculosis. Most children with tuberculosis infection and disease acquire M. tuberculosis from an infectious adult.

Transmission of M. tuberculosis is from person to person, usually by respiratory droplets that become airborne when the ill individual coughs, sneezes, laughs, sighs, or breathes. Infected droplets dry and become droplet nuclei, which may remain suspended in the air for hours, long after the infectious person has left the environment. Only particles less than 10 μm in diameter can reach the alveoli and establish infection.

Several patient-related factors are associated with an increased chance of transmission. Of these, a positive acid-fast smear of the sputum most closely correlates with infectivity. Children with primary pulmonary tuberculosis disease rarely, if ever, infect other children or adults. Tubercle bacilli are relatively sparse in the endobronchial secretions of children with primary pulmonary tuberculosis, and a significant cough is usually lacking. When young children cough, they rarely produce sputum, lacking the tussive force necessary to project and suspend infectious particles of the requisite size. Hospitalized children with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis are placed in respiratory isolation initially. Most infectious patients become noninfectious within 2 weeks of starting effective treatment, and many become noninfectious within several days.

In North America, tuberculosis rates are highest in foreign-born persons from high-prevalence countries, residents of prisons, residents of nursing homes, homeless persons, users of illegal drugs, persons who are poor and medically indigent, health care workers, and children exposed to adults in high-risk groups. Among U.S. urban dwellers with tuberculosis, persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and racial minorities are overrepresented. Most children are infected with M. tuberculosis from household contacts, but outbreaks of childhood tuberculosis centered in elementary and high schools, nursery schools, family day care homes, churches, school buses, and stores still occur. A high-risk adult working in the area has been the source of the outbreak in most cases.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Tuberculosis infection describes the asymptomatic stage of infection with M. tuberculosis, also termed latent tuberculosis. The tuberculin skin test (TST) is positive but the chest radiograph is normal and there are no signs or symptoms of illness. Tuberculosis disease occurs when there are clinical signs and symptoms or an abnormal chest radiograph. The term tuberculosis usually refers to the disease. The interval between latent tuberculosis and the onset of disease may be several weeks or many decades in adults. In young children, tuberculosis usually develops as an immediate complication of the primary infection, and the distinction between infection and disease may be less obvious.

Primary pulmonary tuberculosis in older infants and children is usually an asymptomatic infection. Often the disease is manifested by a positive TST with minimal abnormalities on the chest radiograph, such as an infiltrate with hilar lymphadenopathy or Ghon complex. Malaise, low-grade fever, erythema nodosum, or symptoms resulting from lymph node enlargement may occur after the development of delayed hypersensitivity.

Progressive primary disease is characterized by a primary pneumonia that develops shortly after initial infection. Progression to pulmonary disease or disseminated miliary disease, or progression of central nervous system (CNS) granulomas to meningitis occurs most commonly in the first year of life. Hilar lymphadenopathy may compress the bronchi or trachea.

Tuberculous pleural effusion, which may accompany primary infection, generally represents the immune response to the organisms and most commonly occurs in older children or adolescents. Pleurocentesis reveals lymphocytes and an increased protein level, but the pleural fluid usually does not contain bacilli. A pleural biopsy may be necessary to obtain tissue to confirm the diagnosis by showing the expected granuloma formation and acid-fast organisms.

Reactivation pulmonary tuberculosis, common in adolescents and typical in adults with tuberculosis, usually is confined to apical segments of upper lobes or superior segments of lower lobes. There is usually little lymphadenopathy and no extrathoracic infection because of established hypersensitivity. This is a manifestation of a secondary expansion of infection at a site seeded years previously during primary infection. Advanced disease is associated with cavitation and endobronchial spread of bacilli. Symptoms include fever, night sweats, malaise, and weight loss. A productive cough and hemoptysis often herald cavitation and bronchial erosion.

Tuberculous pericarditis usually occurs when organisms from the lung or pleura spread to the contiguous surfaces of the pericardium. Accumulation of fluid with lymphocytic infiltration occurs in the pericardial space. Persistent inflammation may result in a cellular immune response with rupture of granulomas into the pericardial space and the development of constrictive pericarditis. In addition to antimycobacterial therapy, tuberculous pericarditis is managed with corticosteroids to decrease inflammation.

Lymphadenopathy is common in primary pulmonary disease. The most common extrathoracic sites of lymphadenitis are the cervical, supraclavicular, and submandibular areas (scrofula). Enlargement may cause compression of adjacent structures. Miliary tuberculosis refers to widespread hematogenous dissemination to multiple organs. The lesions are of roughly the same size as a millet seed, from which the name miliary is derived. Miliary tuberculosis is characterized by fever, general malaise, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, night sweats, and hepatosplenomegaly. Diffuse bilateral pneumonitis is common, and meningitis may be present. The chest radiograph reveals bilateral miliary infiltrates, showing overwhelming infection. The TST may be nonreactive as a result of anergy. Liver or bone marrow biopsy is useful for the diagnosis.

Tuberculous meningitis most commonly occurs in children under 5 years old and often within 6 months of primary infection. Tubercle bacilli that seed the meninges during the primary infection replicate, triggering an inflammatory response. This condition may have an insidious onset, initially characterized by low-grade fever, headache, and subtle personality change. Progression of the infection results in basilar meningitis with impingement of the cranial nerves and is manifested by meningeal irritation and eventually increased intracranial pressure, deterioration of mental status, and coma. Computed tomography (CT) scans show hydrocephalus, edema, periventricular lucencies, and infarctions. CSF analysis reveals pleocytosis (50–500 leukocytes/mm3), which early in the course of disease may be either lymphocytes or polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Glucose is low, and protein is significantly elevated. Acid-fast bacilli are not detected frequently in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by either routine or fluorescent staining procedures. Although culture is the standard for diagnosis, PCR for M. tuberculosis is useful to confirm meningitis. Treatment regimens for tuberculous meningitis generally include four antituberculosis drugs and corticosteroids.

Skeletal tuberculosis results from either hematogenous seeding or direct extension from a caseous lymph node. This is usually a chronic disease with an insidious onset that may be mistaken for chronic osteomyelitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Radiographs reveal cortical destruction. Biopsy and culture are essential for proper diagnosis. Tuberculosis of the spine, Pott’s disease, is the most common skeletal site followed by the hip and the fingers and toes (dactylitis).

Other forms of tuberculosis include abdominal tuberculosis that occurs from swallowing infected material. This is a relatively uncommon complication in developed nations where dairy herds are inspected for bovine tuberculosis. Tuberculous peritonitis is associated with abdominal tuberculosis and presents as fever, anorexia, ascites, and abdominal pain. Urogenital tuberculosis is a late reactivation complication and is rare in children. Symptomatic illness presents as dysuria, frequency, urgency, hematuria, and sterile pyuria.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

Tuberculin Skin Test

The TST response to tuberculin antigen is a manifestation of a T cell–mediated delayed hypersensitivity and is the most important diagnostic tool for tuberculosis. It is usually positive 2 to 6 weeks after onset of infection (occasionally 3 months) and at the time of symptomatic illness. The Mantoux test, an intradermal injection of 5 TU (tuberculin units) (intermediate test strength) of Tween-stabilized purified tuberculous antigen (purified protein derivative standard [PPD-S]) usually on the volar surface of the forearm, is the standard for screening high-risk populations and for diagnosis ill patients or contacts. False negative responses may occur early in the illness, with use of inactivated antigen (as a result of poor storage practice or inadequate administration), or as a result of immunosuppression (secondary to underlying illness, AIDS, malnutrition, or overwhelming tuberculosis). Tests with questionable results should be repeated after several weeks of therapy and adequate nutrition. Because of poor nutrition, a high proportion of internationally adopted children arriving in the United States have an initial false positive tuberculin skin test. All internationally adopted children with an initially negative tuberculin skin test should have a repeat tuberculin skin test after 3 months in the United States.

The only TST that should be used in ordinary practice is the 5-TU test (Mantoux test). It is interpreted based on the host status and size of induration (Table 124-1). Only persons at high risk should be offered a Mantoux test (Table 124-2). When persons at low risk are given the TST, the positive predictive value of a positive test decreases, and persons with active tuberculosis (mainly those with asymptomatic infection with atypical mycobacteria) are subjected to unnecessary treatment.

TABLE 124-1 Criteria for Positive Tuberculin Skin Test Results in Clinically Defined Pediatric Populations*

| Positive Result | Population(s) |

|---|---|

| Induration ≥5 mm |

Children receiving immunosuppressive therapy‡ or with immunosuppressive conditions, including HIV infection

|

| Induration ≥10 mm | |

| Induration ≥15 mm | Children ≥4 years of age without any risk factors |

* These criteria apply regardless of previous bacille Calmette-Guérin immunization. Erythema at tuberculin skin test site does not indicate a positive test result. Tuberculin reactions should be read at 48 to 72 hours after placement.

† Evidence by physical examination or laboratory assessment that would include tuberculosis in the working differential diagnosis (e.g., meningitis).

‡ Including immunosuppressive doses of corticosteroids.

TABLE 124-2 Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) Recommendations for Infants, Children, and Adolescentsa

Children for Whom Immediate TST or IGRA is Indicated:b

Children Who Should Have Annual TST or IGRA:c

Children at Increased Risk of Progression of LTBI to Tuberculosis Disease:

Children with other medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, malnutrition, and congenital or acquired immunodeficiencies deserve special consideration. Without recent exposure, these people are not at increased risk of acquiring tuberculosis infection. Underlying immune deficiencies associated with these conditions theoretically would enhance the possibility for progression to severe disease. Initial histories of potential exposure to tuberculosis should be included for all of these patients. If these histories or local epidemiologic factors suggest a possibility of exposure, immediate and periodic TST or IGRA should be considered. An initial TST or IGRA should be performed before initiation of immunosuppressive therapy, including prolonged steroid administration, use of tumor necrosis factor–alpha antagonists, or other immunosuppressive therapy in any child requiring these treatments.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection.

a Bacille Calmette-Guérin immunization is not a contraindication to a TST.

b Beginning as early as 3 months of age.

c If the child is well, the TST or IGRA should be delayed for up to 10 weeks after return.

Recommendations from American Academy of Pediatrics. Tuberculosis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009: page 684.

A whole blood test of interferon-gamma (INF-γ) (Quanitferon gold), a cytokine elaborated by lymphocytes in response to tuberculosis antigens, is currently the recommended diagnostic test for persons older than 5 years of age in the United States. It has similar sensitivity as the TST but improved specificity as it is unaffected by prior bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination or exposure to nontuberculous mycobacterial antigens.

Culture

The ultimate diagnostic confirmation relies on culture of the organism, a process that usually is more successful with tissue, such as pleura or pericardial membrane from biopsy rather than only pleural or pericardial fluid. Sputum is an excellent source for diagnosis in adults but is difficult to obtain in young children. Induced sputum or gastric fluid obtained via an indwelling nasogastric tube with samples taken before or immediately on waking contains swallowed sputum and provides appropriate samples in young children. Large volumes of fluid (CSF, pericardial fluid) yield a higher rate of recovery of organisms, but slow growth of the mycobacteria makes culture less helpful in very ill children. When the organism is grown, drug susceptibilities should be determined because of the increasing incidence of resistant organisms. Antigen detection and DNA probes have expedited diagnosis, especially with CNS disease.

Diagnostic Imaging

Because many cases of pulmonary tuberculosis in children are clinically relatively silent, radiography is a cornerstone for the diagnosis of disease. The initial parenchymal inflammation is not visible radiographically. A localized, nonspecific infiltrate with an overlying pleural reaction may be seen, however. This lesion usually resolves within 1 to 2 weeks. All lobar segments of the lung are at equal risk of being the focus of the initial infection. In 25% of cases, two or more lobes of the lungs are involved, although disease usually occurs at only one site. Spread of infection to regional lymph nodes occurs early.

The hallmark of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis is the relatively large size and importance of the hilar lymphadenitis compared with the less significant size of the initial parenchymal focus, together historically referred to as the Ghon complex (with or without calcification of the lymph nodes). Hilar lymphadenopathy is inevitably present with childhood tuberculosis but it may not be detected on a plain radiograph if calcification is not present. Partial bronchial obstruction caused by external compression from the enlarging nodes can cause air trapping, hyperinflation, and lobar emphysema. Occasionally, children have a picture of lobar pneumonia without impressive hilar lymphadenopathy. If the infection is progressively destructive, liquefaction of the lung parenchyma leads to formation of a thin-walled primary tuberculous cavity. Adolescents with pulmonary tuberculosis may develop segmental lesions with hilar lymphadenopathy or the apical infiltrates, with or without cavitation, that are typical of adult reactivation tuberculosis.

Radiographic studies aid greatly in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in children. Plain radiographs, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the tuberculous spine usually show collapse and destruction of the vertebral body with narrowing of the involved disk spaces. Radiographic findings in bone and joint tuberculosis range from mild joint effusions and small lytic lesions to massive destruction of the bone.

In tuberculosis of the CNS, CT or MRI of the brains of patients with tuberculous meningitis may be normal during early stages of the infection. As disease progresses, basilar enhancement and communicating hydrocephalus with signs of cerebral edema or early focal ischemia are the most common findings. In children with renal tuberculosis, intravenous (IV) pyelograms may reveal mass lesions, dilation of the proximal ureters, multiple small filling defects, and hydronephrosis if ureteral stricture is present.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of tuberculosis includes a multitude of diagnoses because tuberculosis may affect any organ and in early disease the symptoms and signs may be nonspecific. In pulmonary disease, tuberculosis may appear similar to pneumonia, malignancy, and any systemic disease in which generalized lymphadenopathy occurs. The diagnosis of tuberculosis should be suspected if the TST is positive or if there is history of tuberculosis in a close contact.

The differential diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenopathy includes infections caused by atypical mycobacteria, cat-scratch disease, fungal infection, viral or bacterial disease, toxoplasmosis, sarcoidosis, drug reactions, and malignancy. The diagnosis may be confirmed by fine needle aspiration but may necessitate excisional biopsy accompanied by appropriate histologic and microbiologic studies.

TREATMENT

The treatment of tuberculosis is affected by the presence of naturally occurring drug-resistant organisms in large bacterial populations, even before therapy is initiated, and the fact that mycobacteria replicate slowly and can remain dormant in the body for prolonged periods. Although a population of bacilli as a whole may be considered drug susceptible, a subpopulation of drug-resistant organisms occurs at fairly predictable frequencies of 105 to 107, depending on the drug. Cavities may contain 109 tubercle bacilli with thousands of organisms resistant to any one drug, but only rare organisms that are resistant to multiple drugs. The chance that an organism is naturally resistant to two drugs is on the order of 1011 to 1013. Because populations of this number rarely occur in patients, organisms naturally resistant to two drugs are essentially nonexistent.

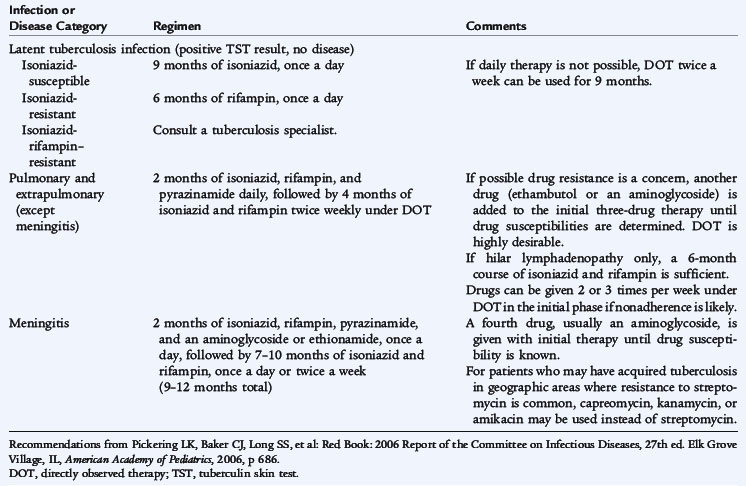

For patients with large populations of bacilli, such as adults with cavities or extensive infiltrates, at least two antituberculosis drugs must be given. For patients with tuberculosis infection but no disease, the bacterial population is small and a single drug, such as isoniazid, can be given. Therapy for latent infection is aimed at eradicating the presumably small inoculum of organisms sequestered within macrophages and suppressed by normal T cell activity. To prevent reactivation of these latent bacilli, therapy with a single agent (usually isoniazid for 9 months) is suggested. Children with primary pulmonary tuberculosis and patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis have medium-sized populations in which significant numbers of drug-resistant organisms may or may not be present. In general, these patients are treated with at least two drugs (Table 124-3) for a prolonged course, typically 9 to 12 months, depending on the type of disease. Isoniazid and rifampin are bactericidal for M. tuberculosis and are effective against all populations of mycobacteria. Along with pyrazinamide, they form the backbone of the antimicrobial treatment of tuberculosis. Other drugs are used in special circumstances, such as tuberculous meningitis and antibiotic-resistant tuberculosis. Ethambutol, ethionamide, streptomycin, and cycloserine are bacteriostatic and are used with bactericidal antituberculosis agents to prevent emergence of resistance.

TABLE 124-3 Recommended Treatment Regimens for Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis in Infants, Children, and Adolescents

A 9-month regimen of isoniazid and rifampin cures greater than 98% of cases of drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis. After daily administration for the first 1 to 2 months, both drugs can be given daily or twice weekly for the remaining 7 to 8 months, with equivalent results and low rates of adverse reactions. The addition of pyrazinamide for the first 2 months of the regimen reduces the total duration of treatment to 6 months and has similar efficacy. Noncompliance, or nonadherence, is a major problem in tuberculosis control because of the long-term nature of treatment and the sometimes difficult social circumstances of the patients. As treatment regimens become shorter, adherence assumes an even greater importance. Improvement in compliance occurs with directly observed therapy, which means that the health care worker is physically present when the medications are administered, and is the standard of care in most settings.

COMPLICATIONS AND PROGNOSIS

Tuberculosis of the spine may result in angulation or gibbus formation that requires surgical correction after the infection is cured. With extrapulmonary tuberculosis, the major problem is often delayed recognition of the cause of disease and delayed initiation of treatment. Most childhood tuberculous meningitis occurs in developing countries, where the prognosis is poor.

In general, the prognosis of tuberculosis in infants, children, and adolescents is excellent with early recognition and effective chemotherapy. In most children with pulmonary tuberculosis, the disease completely resolves, and ultimately radiographic findings are normal. The prognosis for children with bone and joint tuberculosis and tuberculous meningitis depends directly on the stage of disease at the time antituberculosis medications are started.

PREVENTION

Tuberculosis control programs involve case finding and treatment, which interrupts secondary transmission of infection from close contacts. Infected close contacts are identified by positive TST reactions and can be started on appropriate treatment to prevent transmission.

Prevention of transmission in health care settings involves appropriate physical ventilation of the air around the source case. Offices, clinics, and hospital rooms used by adults with possible tuberculosis should have adequate ventilation, with air exhausted to the outside (negative-pressure ventilation). Health care providers should have annual TSTs.

The only available vaccine against tuberculosis is the BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin) vaccine. The original vaccine organism was a strain of Mycobacterium bovis attenuated by subculture every 3 weeks for 13 years. The preferred route of administration is intradermal injection with a syringe and needle because this is the only method that permits accurate measurement of an individual dose. The official recommendation of the World Health Organization is a single dose administered during infancy. In the United Kingdom, a single dose is administered during adolescence following a negative TST. In many countries, the first dose is given in infancy and then one or more additional vaccinations are given during childhood. In some countries, repeat vaccination is universal; in others, it is based either on tuberculin negativity or on the absence of a typical scar. This vaccine is not routinely used in the United States. Some studies show BCG to provide 80% to 90% protection from tuberculosis, and other studies show no protective efficacy at all. Many infants who receive BCG vaccine never have a positive TST reaction. When a reaction does occur, the induration size is usually less than 10 mm, and the reaction wanes after several years.