CHAPTER 125 HIV and AIDS

CHAPTER 125 HIV and AIDS

ETIOLOGY

The cause of AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) is HIV (human immunodrficiency virus), a single-stranded RNA virus of the retrovirus family that produces a reverse transcriptase enabling the viral RNA to act as a template for DNA transcription and integration into the host genome. HIV-1 causes 99% of all human cases. HIV-2, which is less virulent, causes 1% to 9% of cases in parts of Africa and is very rare in the United States.

HIV infects human helper T cells (CD4 cells) and cells of monocyte-macrophage lineage via interaction of viral protein gp120 with the CD4 molecule and chemokines (CXCR4 and CCR5) that serve as coreceptors, facilitating membrane fusion and cell entry. Because helper T cells are important for delayed hypersensitivity, T cell–dependent B cell antibody production, and T cell–mediated lymphokine activation of macrophages, their destruction produces a profound combined (B and T cell) immunodeficiency. A lack of T cell regulation and unrestrained antigenic stimulation result in polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia with nonspecific and ineffective globulins. Other cells bearing CD4, such as microglia, astrocytes, oligodendroglia, and placental tissues also may be infected with HIV.

HIV infection is a continuously progressive process with a variable period of clinical latency before development of AIDS-defining conditions. All untreated patients have evidence of ongoing viral replication and progressive CD4 lymphocyte depletion. There are no overt manifestations of immunodeficiency until CD4 cell numbers decline to critical threshold levels. Quantitation of the viral load has become an important parameter in management.

Horizontal transmission of HIV is by sexual contact (vaginal, anal, or orogenital), percutaneous contact (from contaminated needles or other sharp objects), or mucous membrane exposure to contaminated blood or body fluid. Transmission by contaminated blood and blood products has been eliminated in developed countries, but still occurs in developing countries. Vertical transmission of HIV from mother to infant may occur transplacentally in utero, during birth, or by breastfeeding. Risk factors for perinatal transmission include prematurity, rupture of membranes more than 4 hours, and high maternal circulating levels of HIV at delivery. Perinatal transmission can be decreased from approximately 25% to less than 8% with antiretroviral treatment of the mother before and during delivery and postnatal treatment of the infant. Breastfeeding by HIV-infected mothers increases the risk of vertical transmission by 30% to 50%. In untreated infants, the mean incubation interval for development of an AIDS-defining condition after vertical transmission is 5 months (range, 1 to 24 months) compared with an incubation period after horizontal transmission of generally 7 to 10 years.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Worldwide, as of 2007, approximately 35 million persons have been infected with HIV, including 2.5 million children. More than 25 million persons have died of AIDS, with 80% of the deaths in Africa. An estimated 2.5 million persons worldwide acquired HIV in 2007. In areas of Africa and Asia, infection rates of 40% are largely the result of heterosexual transmission. There are more than 900,000 persons who have been diagnosed with AIDS in the United States, including 9300 children less than 13 years of age. In 2006, approximately 435,000 people were living with HIV/AIDS including approximately 6000 children who were infected perinatally. There were an estimated 56,300 new HIV infections in the United States in 2006.

Vertical transmission accounts for more than 90% of all cases of AIDS in children in the United States. Currently, approximately 100 to 200 infants are born with HIV infection each year in the United States. The effectiveness of perinatal prophylaxis has reduced dramatically the numbers of new cases of pediatric AIDS in the United States and developed countries. Most pediatric cases now occur in adolescents who engage in unprotected sexual activities.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

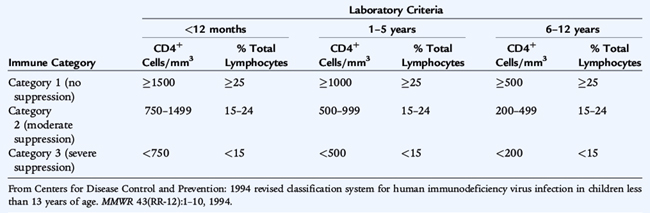

In adolescents and adults, primary infection results in the acute retroviral syndrome that develops after an incubation period of 2 to 6 weeks and consists of fever, malaise, weight loss, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, and often a maculopapular rash. The risk of opportunistic infections and other AIDS-defining conditions is related to the depletion of CD4 T cells. A combination of CD4 cell count and percentage and clinical manifestations is used to classify HIV infection in children (Tables 125-1, 125-2). Initial symptoms with vertical transmission vary and may include failure to thrive, neurodevelopmental delay, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, chronic or recurrent diarrhea, interstitial pneumonia, or oral thrush. These findings may be subtle and remarkable only by their persistence. Manifestations that are more common in children than adults with HIV infection include recurrent bacterial infections, lymphoid hyperplasia, chronic parotid swelling, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, and earlier onset of progressive neurologic deterioration. Pulmonary manifestations of HIV infection are common and include Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, which can present early in infancy as a primary pneumonia characterized by hypoxia, tachypnea, retractions, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase, and fever.

TABLE 125-2 1994 Revised HIV Pediatric Classification System: Clinical Categories

Category N: Not Symptomatic

Category A: Mildly Symptomatic

Category B: Moderately Symptomatic

Category C: Severely Symptomatic

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus infection; HSV, herpes simplex virus; LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia.

From the Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children: Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. Department of Health and Human Services. February 23, 2009. Available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/PediatricGuidelines.pdf. Updated from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1994 revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age. MMWR 43(RR-12):1–10, 1994.

In the United States, most pregnant women are screened and, if indicated, treated for HIV infection. Infants born to HIV-infected mothers receive prophylaxis and are prospectively tested for infection. The diagnosis of HIV infection in most infants born in the United States is confirmed before development of clinical signs of infection.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

HIV infection can be diagnosed definitively by 1 month of age and in virtually all infected infants by 6 months of age using viral diagnostic assays (RNA polymerase chain reaction [PCR], DNA PCR, or virus culture). Maternal antibodies may be detectable until 12 to 15 months of age, and a positive serologic test is not considered diagnostic until 18 months of age.

HIV DNA PCR is the preferred virologic method for diagnosing HIV infection during infancy and identifies 38% of infected infants at 48 hours and 96% at 28 days. Diagnostic viral testing should be performed by 48 hours of age, at 1 to 2 months of age, and at 3 to 6 months of age. An additional test at 14 days of age is often performed because the diagnostic sensitivity increases rapidly by 2 weeks of age. HIV RNA PCR has 25% to 40% sensitivity during the first weeks of life, increasing to 90% to 100% by 2 to 3 months of age. However, a negative HIV RNA PCR cannot be used to exclude infection and, thus, is not recommended as first-line testing. HIV culture is complicated and not routinely performed.

HIV infection of an exposed infant is confirmed if virologic tests are positive on two separate occasions. HIV infection can be reasonably excluded in nonbreastfed infants with at least two virologic tests performed at older than 1 month of age, with one test being performed after 4 months of age, or at least two negative antibody tests performed after 6 months of age, with an interval of at least 1 month between the tests. Loss of HIV antibody combined with negative HIV DNA PCR confirms absence of HIV infection. Persistence of a positive HIV antibody test after 18 months of age indicates HIV infection.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of AIDS in infants includes primary immunodeficiency syndromes and intrauterine infections with cytomegalovirus (CMV) and syphilis. Prominence of individual symptoms, such as diarrhea, may suggest other etiologies.

TREATMENT

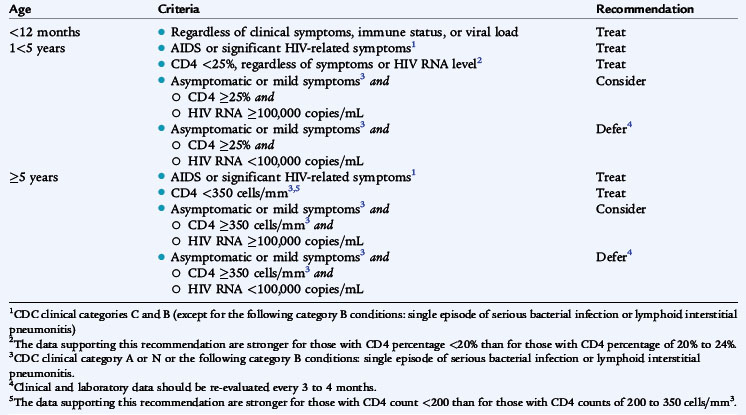

Management of HIV infection in children and adolescents is rapidly evolving and becoming increasingly complex. It should be directed by a specialist in the treatment of HIV infection. Therapy is initiated based on the severity of HIV disease, as indicated by AIDS-defining conditions, and the risk of disease progression, as indicated by CD4 cell count and plasma HIV RNA level (Table 125-3). Initiation of antiretroviral therapy while the patient is still asymptomatic may preserve immune function and prevent clinical progression, but incurs the adverse effects of therapy and may facilitate emergence of drug-resistant virus. Because the risk of HIV progression is fourfold to sixfold greater in infants and very young children, treatment recommendations for children are more aggressive than for adults. All age groups show rapid increases in risk as CD4 cell percentage declines to less than 15%.

Initiation of therapy (Table 125-4) is recommended for infants less than 12 months of age regardless of symptoms of HIV disease or HIV RNA level. Initiation of therapy is recommended for all children 1 to 5 years of age with AIDS or significant HIV-related symptoms or CD4 below 25% (clinical category C or most clinical category B) regardless of symptoms or HIV RNA level. For children older than 5 years with AIDS or significant HIV-related symptoms, CD4 count below 350/mm3 should be treated. Indications for treatment of adolescents and adults include CD4 cell count less than 200 to 350/mm3 or plasma HIV RNA levels above 55,000 copies/mL.

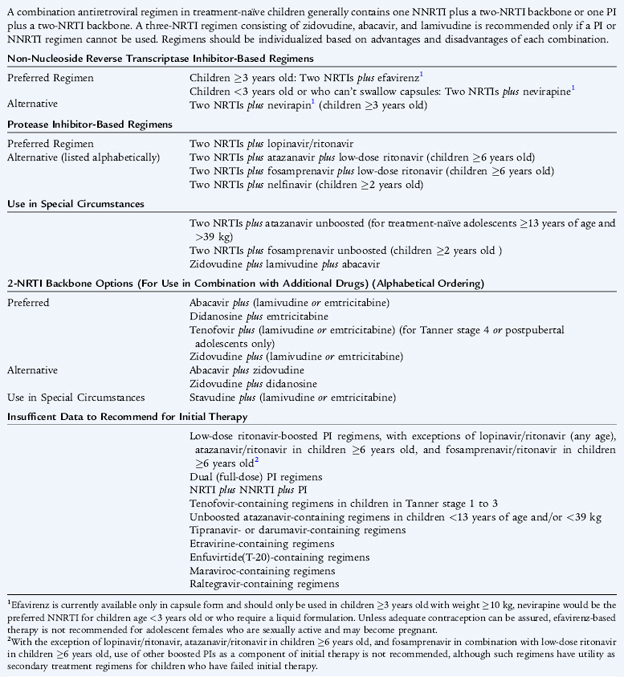

Combination therapy with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is recommended based on the risk of disease progression as determined by CD4 percentage or count and plasma HIV RNA copy number; the potential benefits and risks of therapy; and the ability of the caregiver to adhere to administration of the therapeutic regimen. Antiretroviral regimens include nucleoside analog or nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, and fusion inhibitors (see Table 125-4). Effective combination therapy significantly reduces viral loads and leads to the amelioration of clinical symptoms and opportunistic infections. Combination therapy with dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (zidovudine-lamivudine, zidovudine-didanosine, or stavudine-lamivudine) and a protease inhibitor is a common initial regimen for children.

The ability of HIV to develop resistance to antiretroviral agents rapidly and the development of cross-resistance to several classes of agents simultaneously are major problems. Determination of HIV RNA, CD4 cell count and HIV phenotype and genotype is essential for monitoring and modifying antiretroviral treatment.

Routine immunizations are recommended to prevent vaccine-preventable infections, but may result in suboptimal immune responses. In addition to heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine is recommended for HIV-infected children at 2 years of age, and adolescents and adults with CD4 counts at or above 200/mm3. Because of the risk of fatal measles in children with AIDS, children without severe immunosuppression should receive their first dose of MMR at 12 months of age and may receive the booster as soon as 4 weeks later. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) vaccine should be given only to asymptomatic, nonimmunosuppressed children beginning at 12 months of age as two doses of vaccine at least 3 months apart. Inactivated split influenza virus vaccine should be administered annually to all HIV-infected children at or after 6 months of age. HIV-infected children exposed to varicella or measles should receive varicella zoster immune globulin (VZIG) or immunoglobulin prophylaxis.

COMPLICATIONS

The approach to the numerous opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients involves treatment and prophylaxis for infections likely to occur as CD4 cells are depleted. With potent antiretroviral therapy and immune reconstitution, routine prophylaxis for common opportunistic infections depends on the child’s age and CD4 count. Infants born to HIV-infected mothers receive prophylaxis for P. jirovecii pneumonia with TMP-SMZ (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) beginning at 4 to 6 weeks of age and continued for the first year of life or discontinued if HIV infection is subsequently excluded. TMP-SMZ prophylaxis for P. jirovecii pneumonia for older children and adolescents is provided if CD4 cell counts are less than 200/mm3 or there is history of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Clarithromycin prophylaxis for Mycobacterium avium-complex infection is provided if CD4 cell counts are below 50/mm3. P. jirovecii pneumonia is treated with high-dose TMP-SMZ and corticosteroids. Oral and gastrointestinal candidiasis is common in children and usually responds to imidazole therapy. VZV infection may be severe and should be treated with acyclovir or other antivirals. Recurrent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections also may require long-term antiviral prophylaxis. Other common infections in HIV-infected patients include toxoplasmosis, CMV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, salmonellosis, and tuberculosis.

Children and adults with HIV are prone to malignancies, especially non-Hodgkin lymphomas, with the gastrointestinal tract being the most common site. Leiomyosarcomas are the second most common tumors among HIV-infected children. Kaposi sarcoma, caused by HHV-8, is distinctly rare in children with HIV. It was once common among adults with AIDS and is now infrequent with HAART.

PROGNOSIS

The availability of HAART has improved the prognosis for HIV and AIDS dramatically. Children with opportunistic infections, especially P. jirovecii pneumonia, encephalopathy, or wasting syndrome have the poorest prognosis, with 75% dying before 3 years of age.

PREVENTION

Identification of HIV-infected women before or during pregnancy is crucial to providing optimal therapy for infected women and their infants and to preventing perinatal transmission. Prenatal HIV counseling and testing with consent should be provided for all pregnant women in the United States. Women who use illicit drugs during pregnancy pose special concerns because they are least likely to obtain prenatal care.

The rate of vertical transmission is reduced to less than 8% by chemoprophylaxis with a regimen of zidovudine to the mother (100 mg five times/24 hours orally) started by 4 weeks gestation, continued during delivery (2 mg/kg loading dose intravenously followed by 1 mg/kg/hour intravenously), and then administered to the newborn for the first 6 weeks of life (2 mg/kg every 6 hours orally). Other regimens incorporating single-dose nevirapine for infants have been shown to be similarly effective and are used in developing countries. Currently, combination drug regimens tailored to whether the mother has previously received HIV therapy are recommended. Scheduled cesarean section at 38 weeks to prevent vertical transmission is recommended for women with HIV RNA levels greater than 1000 copies/mL, but it is unclear if cesarean section is beneficial if viral load is less than 1000 copies/mL or when membranes have already ruptured.

Preventing HIV infection in adults decreases the incidence of infection in children. Adult prevention results from behavior changes such as “safe sex” practices, decrease in intravenous drug use, and needle exchange programs. Prevention of pediatric AIDS includes avoidance of pregnancy and breastfeeding (in developed countries) in high-risk women. Screening of blood donors has almost eliminated the risk of HIV transmission from blood products. HIV infection almost never is transmitted in a casual or nonsexual household setting.

Feigin R.D., Cherry J., Demmler G.J., et al. Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2009.

Isaacs D. Evidence-based Pediatric Infectious Disease. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Kliegman R.B., Behrman R.E., Jenson H.B., et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2007.

Long S.S., Pickering L.K., Prober C.G. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E., Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

Pickering L.K., Baker C.J., Long S.S., et al. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006.

Plotkin S.A., Orenstein W.A., Offit P.A. Vaccines, 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2008.