Chapter 8 Appendix

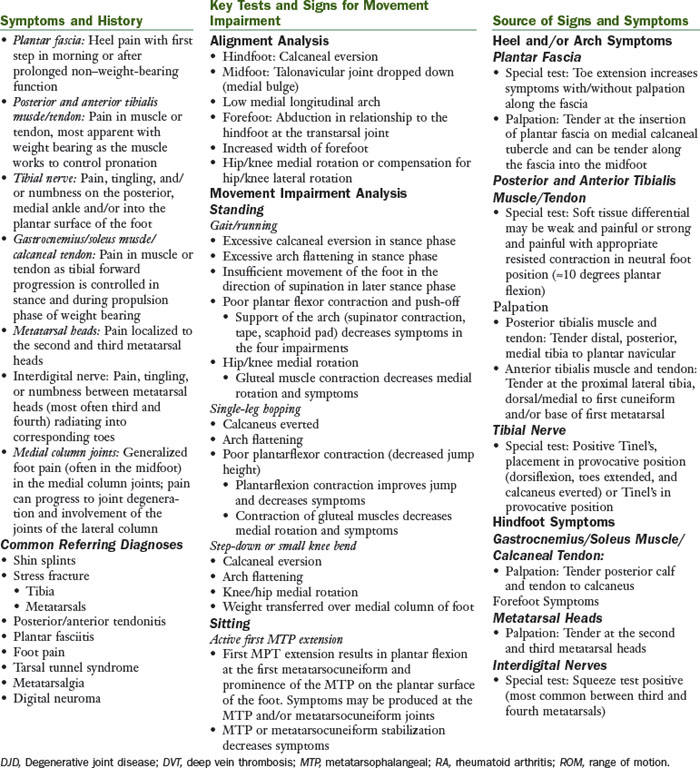

Pronation Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in pronation syndrome is pronation at the foot and ankle. Pronation is considered abnormal and an impairment when the amount of pronation during weight-bearing activities is excessive for that individual and/or when there is insufficient movement of the foot in the direction of supination in later stance phase. The pronation impairment can occur in the hindfoot, midfoot, and/or forefoot. A foot with a pronation movement impairment is a flexible foot that compensates for various structural and movement impairments within the foot and ankle, as well as those at the knee and hip.

Treatment

Walking and/or Running

The patient is instructed to work on the specific cues that assisted in symptom reduction during the examination or the cues that the physical therapist believes with practice may result in symptom reduction. The following cues are among the possibilities that may assist the patient:

Many of the changes being requested of the patient during walking and running are similar to a strengthening program. As such, the patient should be encouraged to have focused practice time and gradual implementation to avoid injury.

Muscle Performance

After the injured tissue has been protected from excessive stresses and the inflammation has subsided, the involved muscle and tendon should undergo a progressive strengthening program and a progressive return to activity. In general, exercise or activity is permissible if pain remains at 2/10 on a 0 to 10 scale. The strengthening exercise should be completed at a minimum of 70% maximal voluntary contraction for 10 repetitions, 3 sets, 3 to 5 times/week.

Decrease Range of Motion

Stretching should be held for 30 seconds, 2 to 3 repetitions, completed regularly throughout the day (5 to 8 times/day), and completed 5 to 7 days/week.

Activity

External Tissue Support

Footwear

Orthoses/Taping

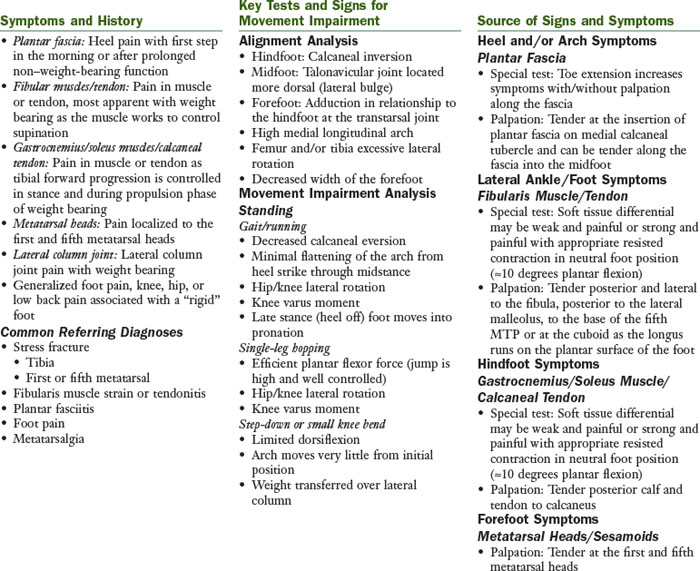

Supination Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in supination syndrome is supination at the foot and ankle. Supination is considered abnormal and an impairment when the amount of supination during weight-bearing activities is excessive for that individual or when it occurs from heel strike to midstance in the gait cycle. The supination impairment can occur in the hindfoot, midfoot, and/or forefoot. The foot with a supination impairment is generally a rigid foot with little or no ability to absorb shock and compensate for structural or movement impairments within the foot and ankle, knee, or hip.

Treatment

Walking and/or Running

The patient is instructed to work on the specific cues that assist in symptom reduction during the examination or the cues that the physical therapist believes, with practice, may result in symptom reduction. Often, the cues are related to softening the landing, hitting more centrally on the heel, and concentrating on trying to limit lateral loading through the foot.

Muscle Performance

After the tissue injury has been protected from excessive stresses and the inflammation has subsided, the involved muscle and tendon should undergo a progressive strengthening program and a progressive return to activity. In general, exercise or activity is permissible if pain remains at 2/10 on a 0 to 10 scale. The strengthening exercise should be completed at a minimum of 70% maximal voluntary contraction for 10 repetitions, 3 sets, 3 to 5 times/week.

Decreased Range of Motion

Stretching should be held for 30 seconds, 2 to 3 repetitions, completed regularly through out the day (5 to 8 times/day), and completed 5 to 7 days/week.

Activity

External Tissue Support

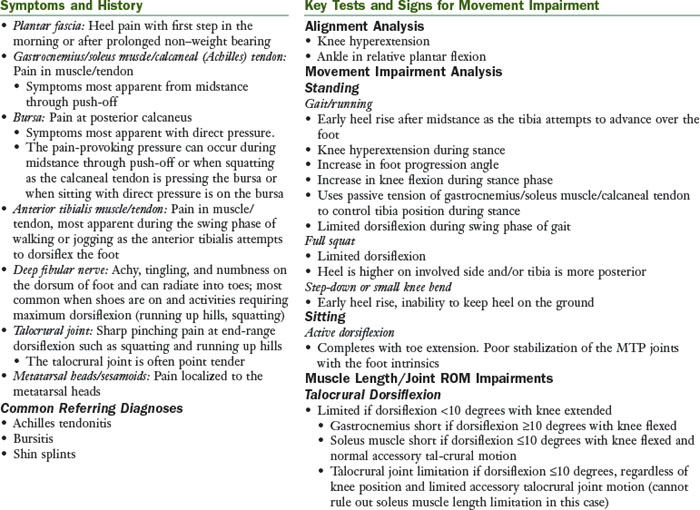

Insufficient Dorsiflexion Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in insufficient dorsiflexion syndrome is insufficient dorsiflexion. The impairment can occur during midstance to push-off or during swing phase and is not associated with excessive supination or pronation.

Treatment

Muscle Performance

After the tissue injury has been protected from excessive stresses and the inflammation has subsided, the involved muscle and tendon should undergo a progressive strengthening program and a progressive return to activity. In general, exercise or activity is permissible if pain remains at 2/10 on a 0 to 10 scale. The strengthening exercise should be completed at a minimum of 70% maximum voluntary contraction for 10 repetitions, 3 sets, 3 to 5 times/week.

Decreased Dorsiflexion

Activity

External Tissue Support

Footwear

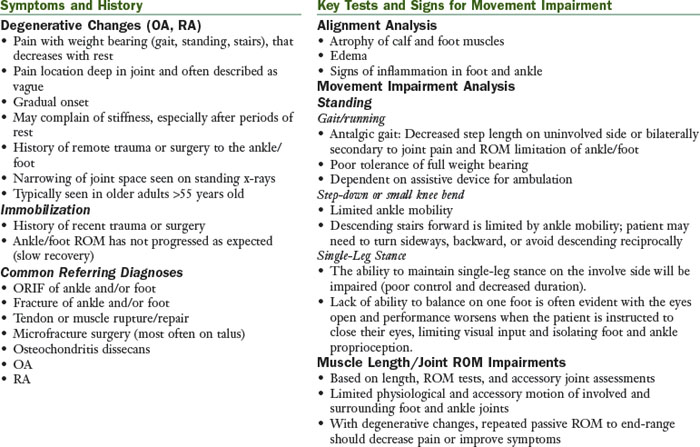

Hypomobility Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in hypomobility syndrome is associated with a limitation in the physiological and accessory motion of the foot and ankle. This may result from degenerative changes in the joint or the effects of prolonged immobilization.

Treatment

Walking and/or Running

Muscle Performance

After the tissue injury has been protected from excessive stresses and the inflammation has subsided, the involved muscle and tendon should undergo a progressive strengthening program and a progressive return to activity. In general, exercise or activity is permissible if pain remains at 2/10 on a 0 to 10 scale. The strengthening exercise should be completed at a minimum of 70% maximum voluntary contraction for 10 repetitions, 3 sets, 3 to 5 times/week.

Decreased Range of Motion

Activity

External Tissue Support

Footwear

Scar

Foot and Ankle Impairment

A key criterion for placement into the foot and ankle impairment classification is the need to protect tissue. Usually, the tissue involved is stressed by a surgical procedure or trauma and may cause significant pain at rest and during movement. The patient is unable to tolerate a typical movement system examination. The limitation in movement is not primarily related to a chronic pain condition. Tissue healing and normal movement are expected. These are general guidelines and not intended to stand alone. Consult the physician’s protocol for specific precautions and progressions. The physical therapist must be familiar with the tissues that were affected in the surgical procedure.

Physiological Factors

Factors that affect the physical stress of tissue and/or thresholds of tissue adaptation and injury1 specific to the foot are as follows.

Tissue Factors

Types of Surgeries (Indications)

Treatment for Foot and Ankle Impairment

Emphasis of treatment is to restore ROM of the ankle and strength of the lower extremity without adding excessive stresses to the injured tissues and within the precautions outlined by the physician. Underlying movement impairments should be addressed during rehabilitation and functional activities to ensure optimal stresses to the healing tissues.

Impairments

Pain

Be sure to clarify the location, quality, and intensity of the pain.

Stage 1

Surgical: Within the first 2 weeks of the postoperative period, some pain will be associated with exercises. Gradually over the next few weeks, pain associated with the exercise should lessen. Pain can be used as a guide to rehabilitation. Sharp, stabbing pain should be avoided. Mild aching is expected after exercises but should be tolerable for the patient. This postexercise discomfort should decrease within 1 to 2 hours of the rehabilitation. A sudden increase in symptoms or symptoms that last longer than 2 hours after exercise may indicate that the rehabilitation program is too aggressive. Coordinating the use of analgesics with exercise sessions is important.

Acute Injury: Despite discomfort, tests may need to be performed to rule out serious injury. Modalities and taping/bracing may be helpful to decrease pain. The patient may also require the use of an assistive device, walker, or crutches in the early phases of healing.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Pain associated with the specific tissue that was involved in the surgery should be decreased by weeks 4 to 6. As the activity level of the patient is progressed, the patient may report increased pain or discomfort with new activities such as returning to daily activities and fitness. Pain or discomfort location should be monitored closely. Muscle soreness is expected, similar to the response of muscle to overload stimulus (e.g., weight training). General muscle soreness should be allowed to resolve, usually 1 to 2 days before repeating the bout of activity. Pain described as stabbing should always be avoided.

Edema

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Edema is quite common in the foot and ankle s/p surgery or injury. The patient should be educated in use of edema-controlling techniques, such as the following:

Patient should be encouraged to keep extremity elevated as much as possible particularly in the early phases (1 to 3 weeks). Application of ice after exercise is recommended. Other methods to control edema in the foot and ankle include electrical stimulation or compression pumps.

Measurement of edema should be taken at each visit. A sudden increase in edema may indicate that the rehabilitation program is too aggressive or the patient possibly has an infection.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Time until swelling is resolved is variable among patients and surgical procedures. As the patient increases the time spent on their feet in regular daily activities or more weight-bearing exercises, the patient may experience a slight increase in edema. This is to be expected; however, the patient should be encouraged to continue to use techniques stated previously to manage the edema.

Appearance

Stage 1

Surgical: Infections should be suspected if the area around the incision or the involved joint is red, hot, and/or swollen. An increase in drainage from the incision, particularly if it has a foul odor or is no longer a clear color, is also indication of an infection. Red streaks following the lymphatic system can also appear with infection. The physician should be consulted immediately if infection is suspected. It is common to observe bruising after surgery. This should be monitored continuously for any changes; an increase in bruising during the rehabilitation phases may indicate infection. Stitches are typically removed in 7 to 14 days.

ROM

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: To prevent contracture, ROM exercises should begin as soon as possible as allowed by the precautions. In the early phases of rehabilitation, the patient should perform ROM exercises at least three times per day and all exercises should be performed within pain tolerance. All uninvolved lower extremity joints should be exercised to prevent the development of restricted ROM at those joints. The typical exercise progression begins with gentle PROM, assisted AROM, or AROM. The choice between PROM, assisted AROM, and AROM is based in part on the tissue injured or repaired. If resistance is allowed, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques, such as contract-relax or hold-relax, can assist in achieving greater ROM. During Stage 1, resistance should be very gentle and can be progressed to a submaximum level as the patient tolerates. When performing ROM exercises of the ankle in the patient with a fracture, attention to hand placement during the exercises can minimize the stresses placed on the healing fracture site. Decreasing pain and edema and improving ROM are typical signs that it is safe to progress the exercises. Refer to specific protocols for guidelines regarding progression of the exercises.

The patient may have ROM precautions per the physician. A common example is tendon transfer with no ROM of the ankle.

Mobilizations to the following specific joints may be indicated (see the next section):

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Precautions are typically lifted by the time the patient reaches this stage. ROM should be approaching normal. Exercises may need to be progressed using passive force. Patient should be instructed that a stretching discomfort is expected; however, sharp pain should be avoided. Mobilizations may be indicated in later stages of rehabilitation to improve ROM. Consult with the physician before initiating joint mobilization after surgery of the knee.

Decreased Dorsiflexion

Muscle Performance

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Strengthening often begins after the initial phase of healing (4 weeks). The emphasis should be placed on proper movement patterns in preparation for strengthening activities. After 4 weeks, strengthening may be gradually incorporated. Progression to resistive exercise is based on the patient’s ability to perform ROM with a good movement pattern and without increase in pain. Weights, Thera-Band, or isokinetic equipment may be used. Specific exercise protocols provided by physicians and physical therapists should be evaluated to ensure that all exercises are appropriate for the individual’s situation. Gastrocnemius/soleus muscles are most commonly affected with surgery or injury to the ankle; however, others may be involved. Electrical stimulation or biofeedback may be used to improve strengthening (see the “Medications, Modalities, and Additional Interventions” section). The patient may have strengthening precautions per the physician.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: After the tissue injury has been protected from excessive stresses and the inflammation has subsided, the involved muscle and tendon should undergo a progressive strengthening program and a progressive return to activity. At this stage, precautions are typically lifted. Strength activities can be progressed as tolerated by the patient. In general, exercise or activity is permissible if pain remains at 2/10 on a 0 to 10 scale. The strengthening exercise should be completed at a minimum of 70% maximum voluntary contraction for 10 repetitions, 3 sets, 3 to 5 times/week.

Proprioception and Balance5-12

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Activities to improve proprioception of the lower extremity should be incorporated as soon as possible. Begin early in treatment, using activities such as weight shifting, progressive increases in weight-bearing function on the involved lower extremity, and then eventually unilateral stance. As the patient improves, the eyes should be closed to increase the challenge for the lower extremity. As the patient can take full weight on the involved lower extremity, activities are progressed to use of a balance board and closed chained activities such as wall sits and lunges.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: In this stage, precautions are typically lifted. Activities should be progressed to prepare patient to return to daily activities, fitness routines, and work or sporting activities. As the patient progresses, proprioception can be challenged by asking the patient to stand on unstable surfaces (pillows, trampoline, or BOSU ball), perturbations can be applied through having the patient catch a ball being thrown to him or her while standing on one leg. Sliding board activities have been shown to be beneficial to patients after surgery.13 The prescription regarding frequency and duration of proprioceptive exercise training remains unclear, but research in this area supports a measurable and sustainable change in balance measures with a maximum of 10 weeks of training, 3 to 5 days/week, for 10 to 15 minutes.6-12

Cardiovascular and Muscular Endurance

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: Stationary bicycle riding can be started early in the rehabilitation if the patient’s weight-bearing precautions allow. If weight-bearing precautions prohibit riding with the involved extremity, unilateral cycling can be performed with the uninvolved extremity. The involved extremity is supported on a stationary surface, while the patient pedals with the uninvolved extremity. The individual should start with low resistance stationary cycling and as strength improves, resistance should be increased. Water walking and swimming are good substitutes for full weight-bearing activities. For swimming, if kicking against the resistance is contraindicated, the patient may participate in swim drills that mainly challenge the upper extremities for conditioning.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: The patient may be progressed to activities such as water walking, to walking on a treadmill, to an elliptical machine, to a Nordic ski machine, to a StairMaster, and then running and hopping when appropriate. The patient should be given specific instructions in gradual progression of these activities. See the “Work, School, and Higher-Level Activities” section for progression of running.

Patient Education

Scar and Sensitivity

Stage 1 to 3

Surgical: The gradual application of stress to scars, incisions, or port holes helps the scar remodel. Exercise, massage, compression, silicone gel sheets, and vibration are used in the management of scar. A hypersensitive scar requires desensitization. A dry incision that has been closed and reopens as the result of the stresses applied with scar massage indicates that the scar massage is too aggressive. Refer to specific guidelines for management of scar for more treatment suggestions. Scars may require desensitization exercises as follows:

Changes in Status

Stage 1 to 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: Consider carefully reports of increased pain or edema or significant change in ROM, especially in combination. The patient should be questioned regarding precipitating events (e.g., time of onset, activity, and so on). If the integrity of the surgery is in doubt, contact the physician promptly. If the patient has fever and erythema spreading from the incision, the physician should be contacted because of the possibility of infection.

Functional Mobility

Basic Mobility

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: The patient should be instructed in mobility while following medical precautions.

Sit to Stand: The patient should be instructed in the proper use of assistive device if a device is indicated and performance maintains prescribed weight-bearing precautions.

Ambulation: The patient may have weight-bearing precautions. The patient should be instructed in the proper use of an assistive device and proper gait pattern. Emphasis should be placed on normalizing the patient’s gait pattern. If the patient is given partial or toe-touch weight-bearing restrictions, the patient should be instructed in using a heel-to-toe pattern while restricting the amount of weight that is accepted by the lower extremity. The patient should not place his weight on the ball of his foot only.

Stairs: The patient should be instructed in the proper stair ambulation with use of an assistive device (if indicated). In the early phases of healing (s/p surgery or acute injury), the patient should be instructed to use a step-to cadence, lead with the involved lower extremity when descending stairs, and lead with the uninvolved lower extremity when ascending stairs.

Stage 2 and 3

All Mobility: As weight-bearing precautions are lifted, the patient should be instructed to gradually reduce the level or type of assistive device required. Progression away from the device depends on the ability of the patient to achieve a normal gait pattern. If the patient demonstrates a significant gait deviation secondary to pain or weakness, the patient should continue to use the device. This may prevent the adaptation of movement impairment and development of pain problems in the future. A progression may be as follows: walker to crutches to one crutch to cane to no assistive device.

Stairs: As the patient progresses through the healing stages and can accept more weight on the involved leg, he or she should be instructed in normal stair ambulation for ascending and descending.

Work, School, and Higher-Level Activities

Stage 1

Surgical/Acute Injury: The patient may be off work or school in the immediate postoperative period or after acute injury. When the patient is cleared to return to work/school, he or she should be instructed in gradual resumption of activities. Emphasis should also be placed on edema control, particularly elevation and compression.

Stage 2 and 3

Surgical/Acute Injury: The patient should be prepared to return to their previous activities. Suggestions for improving proprioception and balance are provided in a previous section. In preparation for the return to sports, sport-specific activities should be added. The initial phases of these activities will include straight plane activities at a slow pace and then gradually increase the level of difficulty. The following sections are examples of activity progression:

Agility Exercises: Emphasis is placed on proper form.

Running: Early in the phases of running, the emphasis is placed on achieving an ideal gait pattern; speed or distance should not be emphasized. Assess gait pattern and instruct as appropriate. Cues are often needed to achieve a heel-toe gait pattern. The patient should run on even and soft surfaces initially. It is expected that the patient may experience some generalized discomfort or swelling with the initiation of running. If this generalized pain and swelling persists longer than 48 hours, then the running must be decreased. If the patient describes a stabbing pain or a pain that is consistent with tissue injury, running should be stopped and the patient reevaluated.

Once the patient can run 1 mile without increasing pain or swelling, begin with other running drills such as the following:

Drills: Once the patient can complete cutting drills without pain or swelling and demonstrates good control of the lower extremity, variations can be added such as the following:

Special notes: If plyometrics and strengthening are to be performed during the same visit, plyometrics should be performed before the strengthening activities.5

Functional testing: Consider functional tests before the patient’s return to sport. There are many functional tests available. The validity of these tests is controversial; however, each test can offer some insight to how the patient may perform in their specific sport. It is recommended that a battery of tests be used to assess the aspects of balance, coordination, agility, and strength. Common test items for the ankle/foot include the following:

Support

Stage 1

Surgical: A brace may be used to protect the surgical site, depending on the procedure or type of fracture. A brace should fit comfortably. The patient should be educated in the timeline for wearing the brace. Refer to specific protocol or consult with physician if the wearing time is not clear.

Stage 2 to 3

Surgical: The recommendations concerning the need for bracing long term are varied. Communication among the team (patient, physician, and physical therapist) is necessary. Functional bracing is recommended if the patient wishes to return to high level sporting activities and demonstrates either laxity in the joint and/or performs poorly on functional tests.

Medications, Modalities, and Additional Interventions

Medications

Surgical: During the acute stage, physical therapy treatments should be timed with analgesics, typically 30 minutes after administration of oral medication. If medication is given intravenously, therapy often can occur immediately after administration. Communication with nurses and physicians is critical to provide optimal pain relief for the patient.

Acute Injury: The patient’s medications should be reviewed to ensure that the patient is taking the medications appropriately.

Modalities: Thermal

Surgical/Acute Injury: Instruct the patient in proper home use of thermal modalities to decrease pain. Ice has been shown to be beneficial, particularly in the immediate postoperative phases.22

Electrical Stimulation

Surgical/Acute Injury: Electrical stimulation can be used for three purposes: Pain relief, edema control, and strengthening. Interferential current has been shown to be helpful in decreasing pain and edema.23-25 Sensory level transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) can assist in decreasing pain.

Currently, there is no definitive answer for the use of electrical stimulation for gastrocnemius/soleus muscle strengthening. It was once believed that electrical stimulation did not provide a distinct advantage over high-intensity exercise training.26,27 However, more recent studies support the use of stimulation to improve motor recruitment and strength.27-30 When strengthening the gastrocnemius/soleus muscles, portable units may not provide adequate stimulation and wall units are preferred; however, recent advances have produced more efficient portable units.

Be sure to check for contraindications. Avoid areas where metal is in close approximation of the skin.

Aquatic Therapy

Surgical/Acute Injury: Aquatic therapy to decrease weight bearing during ambulation may be helpful in the rehabilitation of patients after fracture or surgical procedures. Often, this medium is not available but should be considered if the patient’s progress is slowed secondary to pain or the patient has difficulty maintaining weight-bearing precautions. Incisions must be healed before aquatic therapy is initiated.

Discharge Planning: Equipment

Surgical: Equipment that may be needed depends on the patient’s abilities, precautions, and home environment.

Discharge Planning: Therapy

Assess the need for physical therapy after discharge from an acute stay at a skilled nursing or rehabilitation facility, or if the patient has been discharged from a home health program or outpatient physical therapy.

After the acute phase of recovery, the patient should be reassessed to determine whether a movement impairment diagnosis exists. The patient should be given documentation for consistency of care. Documentation should include the following:

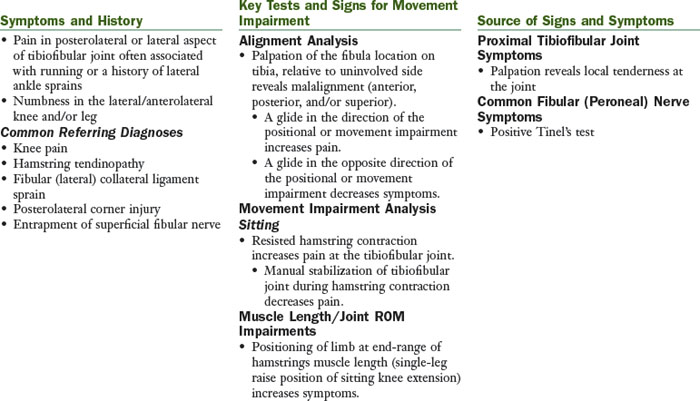

Proximal Tibiofibular Glide Syndrome

The principal movement impairment in proximal tibiofibular glide syndrome is posterior or superior motion of the fibula on the tibia during active hamstring contraction (especially during running). The principal positional impairment is the fibula located anterior, posterior, superior, or inferior to the normal position on the tibia after trauma, particularly an ankle sprain.

Treatment

Muscle Performance

Monitor that patient feels the contraction in the “seat” region; the therapist must palpate to be sure that the patient is recruiting the correct muscles. Common cues for improve performance of the hip lateral rotators include the following:

After the tissue injury has been protected from excessive stresses and the inflammation has subsided, the involved muscle and tendon should undergo a progressive strengthening program and a progressive return to activity. In general, exercise or activity is permissible if pain remains at 2/10 on a 0 to 10 scale. The strengthening exercise should be completed at a minimum of 70% maximum voluntary contraction for 10 repetitions, 3 sets, 3 to 5 times/week.

Decreased Dorsiflexion

Positional Fault

1 Mueller MJ, Maluf KS. Tissue adaptations to physical stress: a proposed “Physical Stress Theory” to guide physical therapist practice, education and research. Phys Ther. 2002;82(4):383-403.

2 Kaeding CC, Yu JR, Wright R, et al. Management and return to play of stress fractures. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(6):442-447.

3 Boytim MJ, Fischer DA, Neumann L. Syndesmotic ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):294-298.

4 Lessard L, Scudds R, Amendola A, et al. The efficacy of cryotherapy following arthroscopic knee surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26(1):14-22.

5 Hewett TE, Paterno MV, Myer GD. Strategies for enhancing proprioception and neuromuscular control of the knee. Clin Orthop. 2002;1(402):76-94.

6 Tropp H, Askling C, Gillquist J. Prevention of ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(4):259-262.

7 Bernier JN, Perrin DH. Effect of coordination training on proprioception of the functionally unstable ankle. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27(4):264-275.

8 Wester JU, Jespersen SM, Nielsen KD, et al. Wobble board training after partial sprains of the lateral ligaments of the ankle: a prospective randomized study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;23(5):332-336.

9 Rozzi SL, Lephart SM, Sterner R, et al. Balance training for persons with functionally unstable ankles. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29(8):478-486.

10 Eils E, Rosenbaum D. A multi-station proprioceptive exercise program in patients with ankle instability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(12):1991-1998.

11 Osborne MD, Chou LS, Laskowski ER, et al. The effect of ankle disk training on muscle reaction time in subjects with a history of ankle sprain. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):627-632.

12 Matsusaka N, Yokoyama S, Tsurusaki T, et al. Effect of ankle disk training combined with tactile stimulation to the leg and foot on functional instability of the ankle. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(1):25-30.

13 Blanpied P, Carroll R, Douglas T, et al. Effectiveness of lateral slide exercise in an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation home exercise program. Phys Ther. 2000;30(10):609-611.

14 Hewett TE, Lindenfeld TN, Riccobene JV, et al. The effect of neuromuscular training on the incidence of knee injury in female athletes. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):699-706.

15 Ross MD, Langford B, Whelan PJ. Test-retest reliability of 4 single-leg horizontal hop tests. J Strength Cond Res. 2002;16(4):617-622.

16 Bolgla LA, Keskula DR. Reliability of lower extremity functional performance tests. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26(3):138-142.

17 Demeritt KM, Shultz SJ, Docherty CL, et al. Chronic ankle instability does not affect lower extremity functional performance. J Athl Train. 2002;37(4):507-511.

18 Nadler SF, Malanga GA, Feinberg JH, et al. Functional performance deficits in athletes with previous lower extremity injury. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12(2):73-78.

19 Petschnig R, Baron R, Albrecht M. The relationship between isokinetic quadriceps strength test and hop tests for distance and one-legged vertical jump test following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(1):23-31.

20 Blackburn JR, Morrissey MC. The relationship between open and closed kinetic chain strength of the lower limb and jumping performance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27(6):430-435.

21 Ross M. Test-retest reliability of the lateral step-up test in young adult healthy subjects. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;25(2):128-132.

22 Lessard L, Scudds R, Amendola A, et al. The efficacy of cryotherapy following arthroscopic knee surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26(1):14-22.

23 Christie AD, Willoughby GL. The effect of interferential therapy on swelling following open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. Physiother Theory Pract. 1990;6:3-7.

24 Johnson MI, Wilson H. The analgesic effects of different swing patterns of interferential currents on cold-induced pain. Physiotherapy. 1997;83:461-467.

25 Young SL, Woodbury MG, Fryday-Field K. Efficacy of interferential current stimulation alone for pain reduction in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized placebo control clinical trial. Phys Ther. 1991;71(Suppl):252.

26 Lieber RL, Silva PD, Daniel DM. Equal effectiveness of electrical and volitional strength training for quadriceps femoris muscles after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. J Orthop Res. 1996;14(1):131-138.

27 Van Swearingen J. Electrical stimulation for improving muscle performance. In: Nelson RM, Hayes KW, Currier DP, editors. Clinical electrotherapy. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1999.

28 Delitto A, Rose SJ, Lehman RC, et al. Electrical stimulation versus voluntary exercise in strengthening the thigh musculature after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Phys Ther. 1988;68:660-663.

29 Stevens JE, Mizner RL, Snyder-Mackler L. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for quadriceps muscle strengthening after bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(1):21-29.

30 Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. A modified neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocol for quadriceps strength training following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(9):492-501.