Documentation of Occupational Therapy Services

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Identify five purposes of documentation.

2 Describe the basic technical points that should be adhered to when writing in the medical record.

3 Explain why only approved abbreviations should be used in occupational therapy documentation.

4 Describe the acceptable method of correcting an error in the medical record.

5 Explain why occupational therapy documentation should reflect the terminology outlined in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework.

6 Describe the components of a well-written progress note.

7 Identify the different places where documentation is required.

8 Briefly summarize the content of the initial evaluation.

9 Define assessments as they apply to the occupational therapy process.

10 Describe the purpose of the intervention plan.

11 Explain why establishment of goals should be a collaborative effort between the client and the therapist.

12 Explain the meaning of “client-centered goal.”

13 Describe the purpose of progress reports.

14 Explain what is meant by a skilled intervention.

15 List the components of a SOAP note and give an example of each component of the note.

16 Identify the purpose of the discharge report.

17 List the primary reimbursement systems of occupational therapy services in the physical disabilities setting.

18 Describe two ways that ensure that confidentiality in documentation is maintained (refer to the AOTA Code of Ethics and HIPAA regulations).

Documentation is an essential component of Occupational Therapy practice. It is the primary method of communication that is used to convey what was done with the client. It demonstrates to others the value of occupational therapy intervention.

Purposes of Documentation

Documentation is a permanent record of what occurred with the client. It is also a legal document and as such must follow the guidelines that will enable it to withstand a legal investigation. Reimbursement depends upon accurate, well-written documentation that provides the necessary information to justify the need for occupational therapy services.

AOTA has identified that the purposes of documentation are as follows:

• Articulate the rationale for provision of occupational therapy services and the relationship of this service to the client’s outcome

• Reflect the therapist’s clinical reasoning and professional judgment

• Communicate information about the client from the occupational therapy perspective

• Create a chronological record of client status, occupational therapy services provided to the client, and client outcomes1

Clear, concise, accurate, and objective information is essential to communicate the occupational therapy process to others. The clinical record should provide sufficient facts to support the need for occupational therapy intervention.13

Documentation is required whenever occupational therapy services are performed. This includes a record of what occurred during direct client care, as well as supportive documentation required to justify the need for occupational therapy intervention.

Best Practices

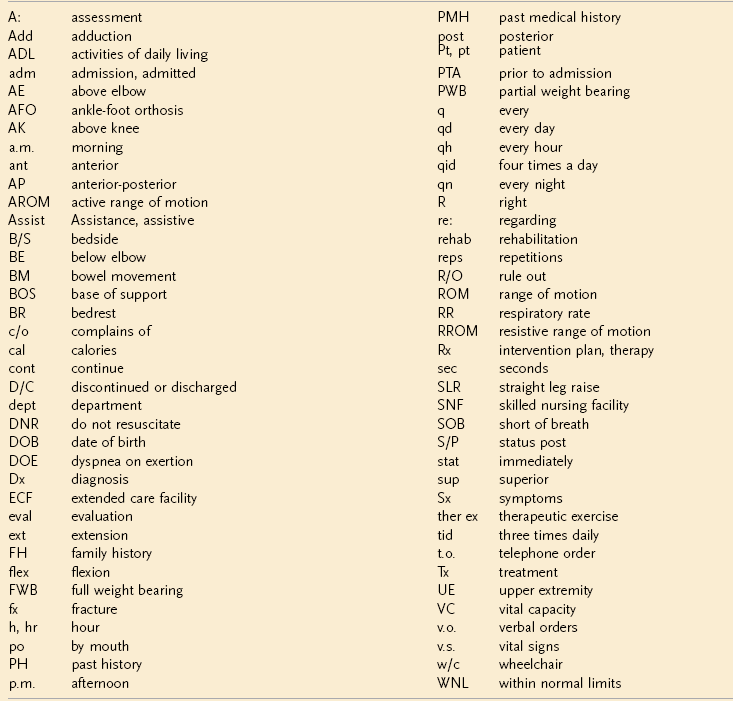

Regardless of where documentation takes place, several basic technical points are important to adhere to when writing in a medical record. Box 8-1 lists the fundamental elements of documentation as set forth by the AOTA.2 Proper grammar, correct spelling and syntax, and well-written sentences are essential components in any professional correspondence. Keeping lists of commonly used terms and using a hand-held spell-check device are two strategies that may assist with spelling difficulties. Poor grammar or inaccurate spelling can lead the reader to question the skills of the therapist. Legibility is important to ensure that misinterpretation does not occur. Only approved abbreviations are to be used in the medical record. All clinical sites should have a printed list of acceptable abbreviations that can be used at the site. It is important to obtain this list and use it as a reference when documenting. Examples of abbreviations commonly used in clinical practice are listed in Box 8-2. Misinterpretation of intended meaning can occur when unfamiliar abbreviations or casual language unsuitable for therapeutic context is used. Language particular to a profession (slang or jargon) should never be used in the client record.

All entries made into the medical record must be signed with the therapist’s legal name. Your professional initials (OTR/L, OTL) should follow your signature. Do not leave blank spaces at the end of an intervention note. Instead, draw a single line that extends from the last word to the signature. This prevents additional information from being added after the entry has been completed.

It is best practice to complete documentation as soon after the therapy session as possible. The longer the time interval between the evaluation or intervention and completion of the written record of the event, the greater the chance that details or other important information will be forgotten. Although documenting at the time of service delivery is ideal, it is not always possible. At these times, it may be beneficial for the therapist to carry a notepad or clipboard to record data that can later be included in the official write-up.

Altering, substituting, or deleting information from the client record should never take place.9 Changes made to the original documentation could be used to support allegations of tampering with the medical record, even when this was not the intent of the writer. However, at times, corrections must be made. Several principles should be followed to avoid questioning of the validity of the information. Never use correction fluid when correcting an entry in the client’s record. An acceptable method of correcting an error in the documentation is to draw a single line through the word or words, initial and date the entry, and indicate that this was an “error.” Do not try to obliterate the sentence or word, as this may appear to be an attempt to prevent others from knowing what was originally written. Late entries to the medical record cannot be backdated. If it is necessary to enter information that is out of sequence (e.g., a note that the therapist forgot to write), it must be entered into the medical record as a “late entry” and must be identified as such.9 Words or sentences cannot be squeezed into existing text “after the fact.” Attempts to do this may be interpreted as adding missing information to support something that occurred after the original documentation was completed.

Do not leave blank spaces on evaluation and preprinted forms. If it is not appropriate to complete a section, “N/A” can be inserted to indicate that the particular area was not addressed. If sections are left blank, others reading the chart may think these areas were overlooked.

Documentation should incorporate the terminology outlined in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-2 (OTPF-2). One of the purposes of the OTPF-2 is to assist therapists in communicating to other professionals, consumers of services, and third party payers the unique focus of occupational therapy on occupation and daily life activities. Documentation should reflect the emphasis of occupational therapy on supporting function and performance in daily life activities and those factors that influence performance (performance skills, performance patterns, activity demands, client factors, context and environment) during the evaluation and intervention process.4 Many practice settings that follow the medical model, such as hospitals, use the term patient to describe the recipient of services. Other settings may prefer the term resident. Although these are acceptable, the OTPF-2 advocates use of the term client. Client encompasses not only the individual receiving therapy, but also others who are involved in the person’s life, such as spouse, parent, child, caregiver, employer, and larger groups such as organizations or communities. The OTPF-2 provides terminology that can be used at each stage of the therapy process. This will be explained in further detail when the various parts of the therapy evaluation, intervention, and discharge processes are described.

Clinical Reasoning Skills

Occupational therapists must use clinical or professional reasoning throughout the occupational therapy process. For the purposes of this chapter, the more contemporary term professional reasoning will be used instead of clinical reasoning when referring to the comprehensive types of thinking and judgment used by occupational therapists in making client-related decisions. Professional reasoning also includes determining how to appropriately document information obtained during the evaluation, intervention, and discharge process. Professional reasoning is used to plan, direct, perform, and reflect upon client care.19 Documentation must demonstrate that professional reasoning was used in the decision-making process during all aspects of the client’s therapy program.

Professional reasoning (also referred to as clinical reasoning by some authors) comprises many different aspects of reasoning: scientific, diagnostic, procedural, narrative, pragmatic, ethical, interactive, and conditional.19 Scientific reasoning is used to help the therapist understand the client’s impairments, disabilities, and performance contexts and to determine how these might influence occupational performance. Diagnostic reasoning is specifically concerned with clinical problem identification related to the client diagnosis. Procedural reasoning is used when the therapist thinks about the disability or disease and decides upon intervention to remediate identified problems. Narrative reasoning guides the therapist in evaluating the meaning that occupational performance limitations might have for the client. Pragmatic reasoning is used when addressing the practical realities associated with delivery of therapy services while looking at the context or contexts within which the client must perform his/her desired occupations. The therapist’s personal situation such as clinical competencies, preferences for particular therapy techniques, commitment to the profession, and comfort level in working with certain clients/diagnoses is a part of the pragmatic reasoning process. Ethical reasoning is the process by which the therapist determines the most appropriate therapy intervention to address the client’s occupational performance needs.19 The therapist’s values and general worldview play an important role in ethical reasoning.11 Keeping these points in mind and using professional reasoning skills when determining what and how to document will facilitate client care and reimbursement for therapy services.

Clinical Reasoning in Documentation

Clinical reasoning is the process used by occupational therapists to plan, direct, perform, and reflect on client care.19 Choosing appropriate assessments based on an understanding of the client’s diagnosis and the areas of occupation that might be affected involves clinical reasoning. Skilled observations, theoretical knowledge, and clinical reasoning are used to identify, analyze, interpret, and document performance components that may contribute to the client’s engagement in occupation. Occupational therapists demonstrate clinical reasoning when they include in their documentation information that demonstrates synthesis of information from the occupational profile, interpretation of assessment data to identify facilitators and barriers to client performance, collaboration with the client to establish goals, and a clear understanding of the demands, skills, and meaning of the activities used in intervention.4 Terminology used in documentation should reflect the unique skilled services that the occupational therapist uses to address client factors, performance skills, performance patterns, context and environment, and activity demands as they relate to the client’s performance. Box 8-3 provides some examples of clinical reasoning.

One of the greatest challenges for students and new therapists is writing notes that are concise yet comprehensive, including all of the relevant information necessary to meet the goals of documentation as described earlier.6 Most third party payers do not reimburse for time spent on documentation, so efficiency becomes essential. Although it is very important to accurately describe what occurred in the therapy session, care must be taken to keep this information to the point, relevant, and specific to established goals identified in the intervention plan. A common error is to describe each event that occurred in the intervention session in a step-by-step format. This is far too time-consuming and in fact does not meet the objectives of good documentation. Rather, short statements should be used that clearly and objectively convey necessary information to the reader. Abbreviations that are approved by and appropriate for the practice setting can be used to save time and space. Customized forms and checklists that include information relevant to the practice setting help to streamline documentation and reduce time spent on narrative writing.

Legal Liability

The medical record is a legal document. All written and computerized therapy documentation must be able to endure a legal review. The medical record may be the most important document in a malpractice suit because it outlines the type and amount of care or services that were given.9 The therapist must know what information is necessary to include in the client record to reduce the risk of malpractice in a legal proceeding. All information must be accurate and based on first-hand knowledge of care. Deductions and assumptions are to be avoided; judgmental statements do not belong in the therapy notes. The therapist instead should describe the action, behavior, or signs and symptoms that are observed. As described earlier, it is considered fraudulent to alter the medical record in any way.

Initial Evaluation

The initial evaluation is a very important document in the occupational therapy process. It is the foundation upon which all other components of the client’s program (including long- and short-term goals, the intervention plan, progress notes, and therapy recommendations) are based. Evaluation is the process of obtaining and interpreting data necessary for understanding the individual, system, or situation. It includes planning for and documenting the evaluation process, results, and recommendations, including the need for intervention.5 The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-24 stresses that the evaluation process should focus on identifying what the client wants and needs to do, as well as on identifying those factors that act as supports for or barriers to performance. The client’s involvement in this process is essential in guiding the therapist in choosing appropriate tools to assess these areas. The occupational therapist takes into account the performance skills, performance patterns, context, activity demands, and client factors that are required for the client to successfully engage in occupation. This information must be articulated in the initial evaluation write-up.

A clear, accurately written accounting of the client’s current status, as well as a description of his/her prior status, is essential to justify the need for occupational therapy services. This initial report also provides necessary information to establish a baseline against which re-evaluation data and progress notes can be compared to demonstrate the efficacy of therapy intervention. The evaluation must clearly “paint a clinical picture” of the client’s current functional status, strengths, impairments, and need for occupational therapy.

The evaluation should include an occupational profile of the client. The occupational profile includes information about the client’s occupational history and experiences, patterns of daily living, interests, values, and needs.4 Information obtained from the occupational profile is essential in guiding the therapist to make clinically sound decisions about appropriate assessments, interventions, and goals.

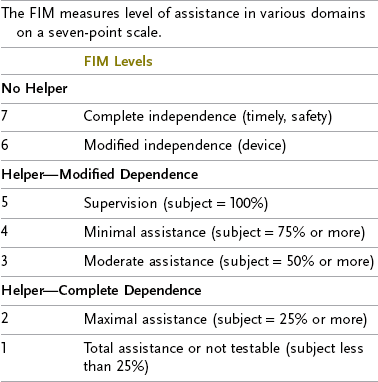

Assessments are the tools, instruments, and interactions used during the evaluation process.5 These include standardized and nonstandardized tests. They can be written tests or performance checklists. Interviews and skilled observations are examples of assessments frequently used in the evaluation process. The specific assessments used are determined by the needs of the client and the practice setting in which the client is being seen. Assessments should be chosen that will evaluate the client’s occupational needs, problems, and concerns. Clinical judgment skills are used to decide which assessments are appropriate and which areas should be evaluated. It is not necessary to evaluate every area of occupation and all performance skills for every individual. For example, it is not appropriate to assess a client’s ability to cook a meal if he/she lives in a setting where meals are provided. Results of the assessment should be clearly identifiable and stated in measurable terminology that is standardized to the practice setting. Table 8-1 shows an example of terminology that can be used to describe the level of assistance required during the performance of a functional task.

TABLE 8-1

| Independent | Client is completely independent. No physical or verbal assistance is required to complete the task. Task is completed safely. |

| Modified independence | Client is completely independent with task, but may require additional time or adaptive equipment. |

| Supervised | Client requires supervision to safely complete task. A verbal cue may be required for safety. |

| Contact guard/standby assistance | Hands-on contact guard assistance is necessary for the client to safely complete the task, or the caregiver must be within arm’s length for safety. |

| Minimum assistance | Client requires up to 25% physical or verbal assistance from one person to safely complete the task. |

| Moderate assistance | Client requires 26% to 50% physical or verbal assistance from one person to safely complete the task. |

| Maximal assistance | Client requires 51% to 75% physical or verbal assistance from one person to safely complete the task. |

| Dependent | Client requires more than 75% assistance to complete the task. Note: It is important to state whether assistance provided is physical or verbal assistance. |

AOTA has outlined the recommended components of professional documentation used in occupational therapy in Guidelines for Documentation of Occupational Therapy.1 Suggestions for what information should be included in evaluation and re-evaluation reports, intervention plans, progress reports, transition plans, and discharge reports are provided.

The evaluation report should contain the following information:

1. Client information: name/agency; date of birth; gender; applicable medical, educational, and developmental diagnosis; precautions; and contraindications

2. Referral information: date and source of referral; services requested; reason for referral; funding source; and anticipated length of service

3. Occupational profile: client’s reason for seeking occupational therapy services; current areas of occupation that are successful and areas that are problematic; contexts that support or hinder occupations; medical, educational, and work history; occupational history; client’s priorities; and targeted outcomes

4. Assessments: types of assessments used and results (e.g., interviews, record reviews, observations, standardized or nonstandardized assessments)

5. Analysis of occupational performance: description and judgment about performance skills; performance patterns; contextual or environmental aspects or features of activities; client factors that facilitate or inhibit performance; and confidence in test results

6. Summary and analysis: interpretation and summary of data as they relate to the occupational profile and referring concerns

7. Recommendation: judgment regarding appropriateness of occupational therapy services or other services

Intervention Plan

Upon completion of the assessment, the intervention plan is established. Information obtained from the occupational profile and the various assessments is analyzed, and a problem list is generated. Problem statements should include a description of the underlying factor (performance skill, performance pattern, client factor, contextual or environmental limitation, activity demand) and its impact on the related area of occupation.7 Based on the client’s specific problems, the intervention plan is developed. The therapist must use theoretical knowledge and professional reasoning skills to develop long- and short-term goals, to decide upon intervention approaches, and to determine the interventions to be used to achieve stated goals. Recommendations and referrals to other professionals or agencies are also included in the plan.1 The intervention plan is formulated on the basis of selected theories, frames of reference, practice models, and evidence.4 It is directed by the client’s goals, values, beliefs, and occupational needs.

Establishment of the intervention plan is a collaborative effort between the therapist and the client or, if the client is unable, the client’s family or caregivers. The plan is based on the client’s goals and priorities.3,4 Although the primary responsibility for development of the intervention plan and goal setting is the role of the occupational therapist, the occupational therapy assistant may contribute to the process.5 Goals must be measurable and directly related to the client’s ability to engage in desired occupations. The overarching goal of occupational therapy intervention is “engagement in occupation to support participation.”4 This must be kept in mind at all times when developing long- and short-term goals. The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-2 further identifies the outcome of occupational therapy intervention to be the method that assists the client to reach a state of physical, mental, and social well-being; to identify and attain aspirations; to satisfy needs; and to change or cope with the environment.4 Documentation that uses this terminology will support the unique focus that occupational therapy contributes to the client care plan and the rehabilitation process.

The client intervention plan contains both short- and long-term goals. Some therapists prefer to use the term objective in place of short-term goal. Short-term goals or objectives are written for specific time periods (e.g., 1 or 2 weeks) within the overall course of the client’s therapy program. They are periodically updated as the client progresses or in accordance with the guidelines of the practice setting or payer requirements. Short-term goals are the steps that lead to accomplishment of the long-term goal, which is also called the discharge goal in some settings. The long-term goal is generally considered to be the overall functional goal of the intervention plan and is broader in nature than the short-term goal. For example, the client’s long-term goal may be to become independent with dressing. One short-term goal to accomplish this might be that the client will be able to independently don and doff a simple pull-over shirt without fasteners. When this short-term goal is achieved, a subsequent goal might be for the client to be able to dress independently in a shirt with buttons. Eventually, lower extremity dressing would be added as an objective, then socks, shoes, and outerwear, until the long-term goal of independent dressing is achieved.

Establishing functional, client-centered goals that focus on engagement in occupations and activities to support participation in life is central to the philosophy of occupational therapy.4 Skillful goal writing requires practice and careful consideration of the desired outcome of therapy intervention. Client-centered goals are written to reflect what the client will accomplish or do, not what the therapist will do, and are written in collaboration with the client. An important characteristic of a goal is that it must reflect an outcome, not the process used to achieve the outcome.16 “The client will be taught energy conservation techniques to use during dressing” is an example of a poorly written goal that focuses on the process, rather than the outcome of therapy. The correct way to write the goal would be “The client will independently use three energy conservation techniques during dressing.” Goals must be objective and measurable and must include a time frame, which may be discussed in a separate section of the evaluation form. The expected behavior is clearly stated, using concrete terms that describe a specific functional task, action, behavior, or activity (the client will don pants); also, a measurable expectation of performance is identified (independently), with conditions or circumstances that support the outcome listed (using a dressing stick). Well-written goals contain all of the components listed here and avoid the use of vague or ambiguous terms that may be misunderstood by the reader (Table 8-2).

TABLE 8-2

Examples of Short- and Long-Term Goals

| Short-Term Goal (to be completed in 2 weeks) | Long-Term Goal (to be completed in 4 weeks) |

| Client will prepare a cup of tea with minimal verbal assistance for safety and technique. | Client will independently adhere to safety precautions during simple cooking tasks 100% of the time. |

| Client will brush teeth with moderate physical and verbal assistance while seated at the sink. | Client will complete morning hygiene and grooming independently after task set-up while seated at the sink. |

| Client will don socks with minimal assistance using a sock aid while seated in a wheelchair. | Client will independently complete lower body dressing without assistive devices while seated at the edge of the bed. |

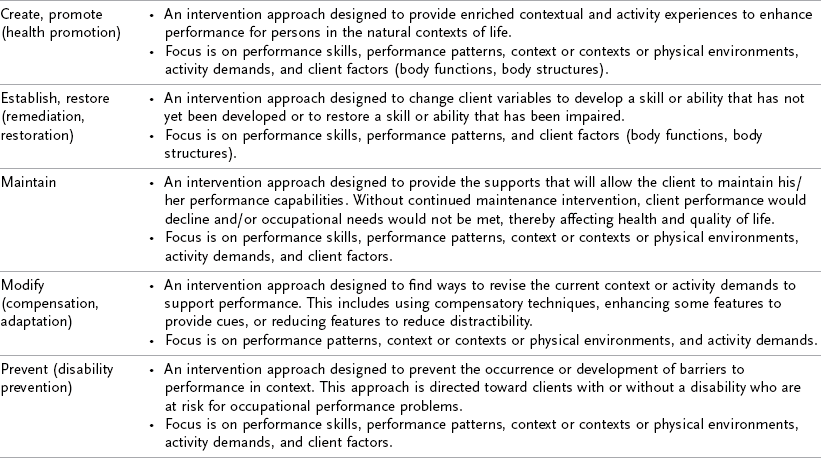

Once goals are established, the therapist, in collaboration with the client, chooses appropriate interventions that will lead to goal attainment. The plan consists of skilled interventions that the therapist will provide throughout the client’s therapy program. Interventions are chosen that involve the therapeutic use of self; the therapeutic use of occupations or activities (occupation-based activity, purposeful activity, preparatory methods); and consultation and client/caregiver education and advocacy.4 Examples of occupational therapy interventions include activities of daily living (ADL) training; instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) training; therapeutic activities; therapeutic exercises; splint/orthotic fabrication, modification, and application; neuromuscular retraining; cognitive-perceptual training; and discharge planning. The OTPF-2 outlines various approaches that may guide the intervention process (Table 8-3). These approaches are based on theory and evidence. It is expected that the intervention plan will be modified according to client needs and priorities and responses to the interventions. Modifications to the intervention plan must be documented in the client record in the weekly or monthly progress report.

Progress Reports

Progress toward goal attainment is an expected criterion for reimbursement of occupational therapy services. Documentation that demonstrates progression toward goal achievement is critical to support the need for ongoing therapy. The purposes of the progress report are to document the client’s improvement, to describe the skilled interventions provided, and to update goals. Progress reports can be written daily or weekly depending on the requirements of the work site and the payer source. Various reporting formats are used to document client progress. The most prevalent formats used in physical disabilities settings include SOAP notes, checklist notes, and narrative notes.

Regardless of the format used, progress reports should identify the following key elements of the intervention session: the client outcome (using measurable terminology from the OTPF-2); the skilled interventions provided by the occupational therapist; and progress that resulted from the occupational therapy intervention. Skilled interventions are those that require the expertise, knowledge, clinical judgment, decision making, and abilities of an occupational therapist.14 Skilled therapy services have a level of inherent complexity such that they can only be performed safely and/or effectively by or under the general supervision of a qualified therapist. Skilled services include evaluation; determination of effective goals and services in collaboration with the client and the client’s caregivers and other medical professionals; analysis and modification of functional activities and tasks; determination that the modified task obtains optimum performance through tests and measurements; client/caregiver training; and periodic re-evaluation of the client’s status with corresponding readjustment of the occupational therapy program. The therapist’s skills may be required for safety reasons, or they may be required to establish and teach the client a compensatory strategy to improve independence and safety. Box 8-4 shows examples of terminology that can be used to demonstrate provision of skilled services.

Documentation of skilled services includes a description of the type and complexity of the skilled intervention and must reflect the therapeutic rationale underlying the task. Reimbursement for clinical services provided is dependent on documentation that demonstrates the clinical reasoning that underlies the intervention. The progress note must reflect progress made toward established goals. Comparison statements are an excellent way to convey this information. Current status information is compared with baseline evaluation findings to clearly identify progress: Client now requires minimal assistance to regain sitting posture during lower body dressing (last week required moderate assistance). Documentation that includes functional assessment scores from validated tests and measurements to demonstrate client progress provides strong justification for reimbursement of therapy services. A statement explaining why additional therapy services are needed substantiates the need for ongoing therapy: Occupational therapy services are required for facilitation of balance and postural corrections during lower body dressing training. Goals are modified and updated on the basis of client progress: Client will don pants independently, without loss of balance, while seated at the edge of the bed. Upgrading of the client’s goals can consist of reducing the amount of assistance required to complete the task, increasing the complexity of the task, or introducing a new component to the activity. This is an ongoing process, and meticulous documentation is necessary to demonstrate the need for continued occupational therapy services.

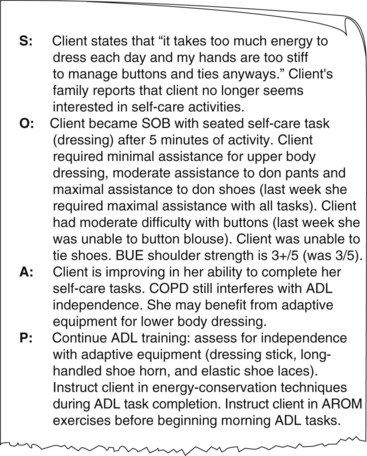

SOAP Notes

The SOAP note format was first introduced by Dr. Lawrence Weed in 1970 as a method of charting in the problem-oriented medical record (POMR).20 In the POMR, which focuses on a client’s problems instead of on his/her diagnosis, a numbered problem list is developed that becomes an important part of the medical record. Each member of the health care team writes a SOAP note to address problems in the list that are specific to his/her area of expertise. The POMR is constantly modified and updated throughout the client’s stay. The SOAP note is one of the most frequently used formats for documenting patient status. Each letter in the acronym SOAP stands for the name of a section of the note:

The subjective (S) part of the note is the section where the therapist includes information reported by the client. Information provided by the family or caregivers can also be included here. Many different types of statements can be included in the subjective section of the SOAP note. Any information that the client gives the therapist about his/her current condition, functional performance, limitations, general health status, social habits, medical history, or goals is appropriate to include in this section.12 A client’s subjective response to treatment is recorded in this section. Direct quotes can be used when appropriate. Family, caregivers and others involved in the client’s care can also provide valuable information. For example, nursing may report that the client was unable to feed himself or herself at breakfast, or a family member may supply information on the client’s normal routine before hospitalization. If the client is nonverbal, gestures, facial expressions, and other types of nonverbal responses are appropriate to include. This information can be used to demonstrate improvement, support the benefit of chosen interventions, document the client’s response, and show client compliance. However, discretion must be used when deciding what information to include. Using careful, effective communication skills during client treatment sessions will enhance the therapist’s ability to gather relevant subjective information about the client’s attitudes and concerns that can be used to ensure proper intervention and appropriate documentation.7

The Subjective section should include only relevant information that will support the therapist’s decision regarding which assessments should be used and which goals are appropriate for this client. The therapist should avoid statements that can be misinterpreted or that can jeopardize reimbursement. Subjective statements that do not relate to information in the other parts of the note are not useful. Negative quotes from the client that do not relate to the intervention session are not necessary or beneficial to include. If there is nothing relevant to report in the Subjective section, it is permissible to not include a statement. In this case, write a circle with a line through it (0) to indicate that you have intentionally left the section blank.18

In the Objective (O) section of the SOAP note, the therapist documents the results of assessments, tests, and measurements performed, as well as objective observations.12 Data that are recorded in the Objective section are measurable, quantifiable, or observable. Only factual information may be included. Results of standardized and nonstandardized tests are documented in this part of the note. Measurable performance of functional tasks (basic activities of daily living [BADL], IADL), range-of-motion (ROM) measurements, muscle grades, results of sensory evaluations, and tone assessments are examples of appropriate information for this section of the SOAP note. It is important that the therapist not interpret or analyze data in the Objective section. Rather, statements should include only concise, specific, objective recordings of the client’s performance. Simply listing the activities that the client engaged in is not sufficient. The emphasis is on the results of the interventions, not on the interventions themselves. Information in the Objective section can be organized chronologically, discussing the results of each treatment event in the order it occurred during the session, or categorically.7 Information that is organized categorically should follow the categories outlined in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-2: performance skills, performance patterns, context, activity demands, and client factors.4 Table 8-4 shows examples of documentation that can be used in the objective section.

TABLE 8-4

Examples of Categories and Documentation for Objective Section of SOAP Note

| Category | Objective Documentation |

| ADL task performance | Note how each of the performance skills and client factors affects completion of ADL tasks. Include assist levels and set-up needed, adaptive equipment required, or techniques used. Include client response to treatment. |

| Posture and balance | Note whether balance was static or dynamic. Note whether the client leans in one direction, has rotated posture, or has even or uneven weight distribution. Note the position of the head and what cues or feedback was necessary to maintain or restore balance. |

| Coordination | Include hand dominance, type of prehension used, ability to grasp and maintain grasp, reach and purposeful release, object manipulation, and gross versus fine motor ability |

| Swelling or edema | Give volumetric measurements if possible, pitting or nonpitting type. |

| Movement patterns in affected upper extremities | Note tone, tremors, synergy pattern, facilitation required, and stabilization. |

| Ability to follow directions | Note type and amount of instruction required and ability to follow one-, two-, or three-step directions. |

| Cognitive status | Report on initiation of task, verbal responses, approach to the task, ability to stay on task, sequencing, orientation, and judgment. |

| Neurologic factors | Note perseveration, sensory losses (specific), motor deficits, praxis, spasticity, flaccidity, rigidity, neglect, bilateral integration, and tremors. |

| Functional mobility | Note type of assistance required for the client to complete all types of mobility. |

| Psychosocial factors | Note client’s overall mood, affect, and ability to engage with others. Also note family support, response to changes in body image, and ability to make realistic discharge decisions. |

From Borcherding S: Documentation manual for writing SOAP notes in occupational therapy, ed 2, Thorofare, NJ, 2005, Slack.

In the Assessment (A) section of the SOAP note, the therapist draws from the subjective and objective findings and interprets the data to establish the most appropriate therapy program. In this section, impairments and functional deficits are analyzed and prioritized to determine what impact they have on the client’s occupational performance and ability to engage in meaningful occupation. Only information that was included in the Subjective or Objective section is discussed in the Assessment section. Clinical reasoning is required to analyze the information and develop the intervention plan. The Asssessment portion of the SOAP note is where the therapist demonstrates his or her ability to summarize relevant assessment findings, synthesize the information, analyze its impact on occupational performance, and utilize it to formulate the intervention plan. It requires keen observation, clinical reasoning, and judgment skills, as well as an ability to identify relevant factors that inhibit or facilitate performance. The Assessment section should end with a statement justifying the need for continued therapy services: Client would benefit from activities that encourage trunk rotation and forward lean to facilitate transfers and lower body dressing.7 Insight and skill in completing the Assessment section improve with clinical experience.

The intervention plan is outlined in the Plan (P) section. As the client achieves the short-term goals, the plan is revised and new short-term goals are established. Documentation reflects the client’s updated goals, as well as any modifications to the frequency of therapy. Suggestions for additional interventions are also included in this section. This information will guide subsequent treatment sessions. Figure 8-1 is an example of a progress note using the SOAP format.

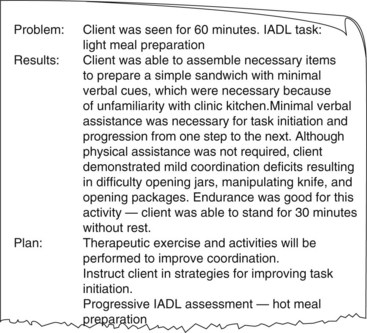

Narrative Notes

The narrative note is another format used to document daily client performance. One way to organize the narrative note is to categorize the information into the following subsections: problem, program, results/progress, and plan. The problem being addressed in the treatment intervention should be clearly identified. The impairment, as well as the functional impact, is stated. The intervention or intervention modality is identified in the program section. The results, including progress, are documented in measurable, objective terminology. Barriers to progress are included in this section. The plan for future intervention is outlined in the plan section. The need to modify goals and the rationale for this would be included here. In some practice settings, the narrative note is written directly in the medical chart. Occupational therapy may have a designated area in the medical chart to write notes, or all clinicians involved with the client may document on a single comprehensive interdisciplinary note. The date and often the beginning and ending times of the therapy session must be included in the note. The therapist’s signature follows the last word of the note. Figure 8-2 is an example of a narrative note using this format.

A narrative format may also be used to write any type of information that the therapist wishes to convey to the other team members. For example, the therapist may document that the evaluation was initiated, or that the client was unable to attend therapy because of illness. Documentation of communication between team members regarding the client’s program may be expressed in a narrative format.

Descriptive Notes

At times, a short descriptive note is useful to relay important information about the client. Although it is preferable to keep notes as objective as possible, it is sometimes appropriate to include subjective information. Judgmental comments, negative statements, comments about other staff members, and information not directly related to the client’s intervention program do not belong in the official medical record. Unobserved behaviors that are included in the client record should be recorded as such and a clear explanation provided as to who provided the information to the therapist.

Progress Checklists or Flow Sheets

Checklists or flow sheets can be used to document daily performance in a concise, efficient manner. High productivity demands in many settings, as well as lack of reimbursement for documentation, have made this type of documentation a useful option. Flow sheets typically use a table or graph format to record measurements at regular intervals, usually after each session. Advantages of using a flow sheet or a checklist to document daily performance on specific tasks include improved clarity and organization of data; reduction in the quantity of data that need to be recorded after each session; improved focus on interventions that are specific to the client’s goals; and ease in clearly identifying the client’s functional status and progress.18 A disadvantage of using this format for documentation is that often space is not sufficient for the therapist to include subjective statements to explain client performance, document the therapist’s interpretation of the objective information, or describe the client’s response to the intervention. The checklist provides a description of what the client did based on a level of assistance or an objective measurement, but it does not provide information on the quality of how the task was accomplished or modifications that were made to facilitate successful completion of the task. However, this information can be included in a narrative format on a separate note sheet. Information from the daily checklist or flow sheet is used to write a weekly progress note.

RUMBA

According to Perinchief,17 a tool such as the RUMBA (also called RHUMBA) test can be beneficial in organizing the therapist’s thought processes for effective documentation. RUMBA and RHUMBA are acronyms; each letter identifies something that the therapist should keep in mind when writing goals and documenting the therapeutic process8:

• Is the information Relevant (the outcome must be relevant)? The goal/outcome must relate to something.

• How long will it take? Indicate when the goal/outcome will be met.

• Is the information Understandable? Anyone reading it must know what it means.

• Is the information Measurable? There must be a way to know when the goal has been met.

• Is the information Behavioral (describes behaviors)? The goal/outcome must be something that is seen or heard.

• Is the outcome Achievable (realistic)? The goal/outcome must be do-able and realistic.

The therapist can review the documentation to determine whether these questions have been answered, all the while keeping the target audience in mind.

SMART

Another system that may assist the therapist in writing goals is SMART goals. SMART acronyms stand for significant (and simple), measurable, achievable, related, and time-limited.18

• Achieving this goal will make a Significant difference in the client’s life.

• You have a clear, Measurable target to aim for, and you will know when the client has reached the goal.

• It is reasonable that the client could Achieve this goal in the time allotted.

• Long- and short-term goals Relate to each other, and the goal has a clear connection to the client’s occupational needs.

• The goal is Time-limited: Short- and long-term goals have a designated chronological end point.8

Discharge Reports

Discharge reports are written at the conclusion of the therapy program. A comparison statement of functional performance from initial evaluation to discharge is documented to demonstrate progress. Emphasis should be placed on the progress the client has made in engaging in occupations. A summary of the skilled interventions provided to the client is also included. Discharge recommendations (e.g., home programs, therapy follow-up, referral to other programs) are made to facilitate a smooth transition from therapy. Clients are discharged from therapy when they have achieved established goals, have received maximal benefit from occupational therapy services, have refused to participate in further therapy, or have exceeded reimbursement allowances. The discharge summary should clearly demonstrate the efficacy of occupational therapy services and is often used to obtain information for outcome studies.

Types of Documentation Reporting Formats

Documentation can be paper based (written record) or computer generated. The written medical record is still the most widely used method for recording information; however, the electronic medical record (EMR) is becoming more common, especially in large hospital settings. Computerized documentation can be used to record all aspects of the occupational therapy process from the evaluation report to the discharge report. Reporting forms can be inputted into the computer, and results of initial evaluation and the discharge report can be typed directly onto the forms. This guarantees legibility and ensures that no areas are left uncompleted. Increased numbers of regulations, more complex reimbursement structures, and pressure to achieve increased productivity are placing pressure on our current systems; therefore, use of an electronic documentation program may improve therapists’ efficiency.10

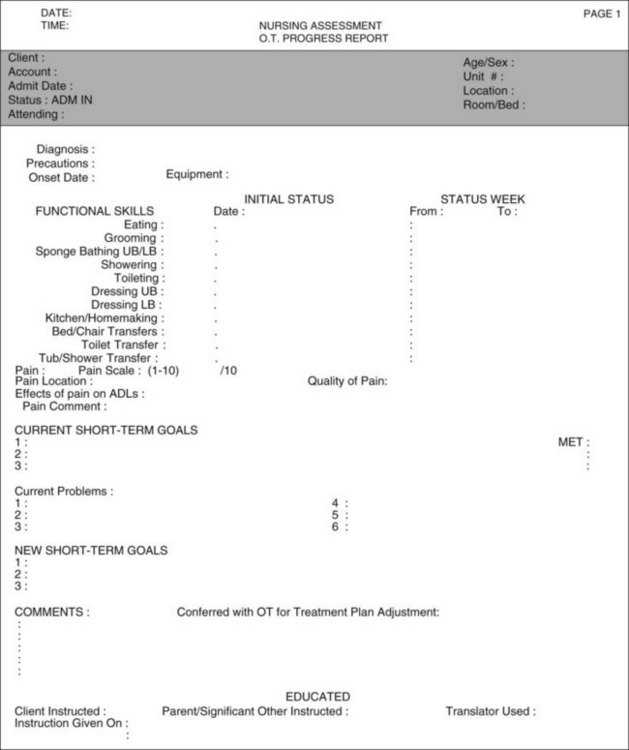

Computerized evaluation forms and progress notes are formatted to meet the needs of the facility and include information required for reimbursement (Figure 8-3). Therapists often are able to choose responses from a pull-down menu, thereby reducing time spent in deciding upon the appropriate terminology to use (Table 8-5). Space is usually available to include narrative information as well. Because all health care providers enter information on a common database, members of the team are able to quickly access information about the patient by reviewing relevant sections on the computerized medical chart. One of the problems or inconveniences that may occur with computerized documentation involves the accessibility of computers. Therapists must allow time to locate a computer that is not in use, so that they can enter their data. Because notes must be entered in chronological order, this sometimes becomes an issue if a computer is not available, as the therapist may not be able to wait until the next day to enter information. Some forms that are on the computer are very restrictive in terms of what information the therapist may enter. This may make it difficult for the therapist to adequately document the session. Often a long time lapse occurs between updates of computer programs. In general, however, computerized documentation and billing can be an asset in the therapy setting. It can enhance therapist productivity by reducing the amount of time spent writing and can guide the new therapist in choosing appropriate responses and terminology to document what occurred with the client.

Many different written formats can be used to document occupational therapy services. The content of the form used is usually determined by the requirements of the third party payer reimbursing the service and the unique needs of the practice setting. As stated before, documentation must contain the information necessary to justify the need for occupational therapy services, must demonstrate the provision of skilled therapeutic interventions, and must show client progress toward identified goals. Occupational therapy documentation should address all of these components to ensure reimbursement and to convey accurate information about client performance.

The primary reimbursement systems for occupational therapy services in the physical disabilities setting include Medicare, Medicaid, and various Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) and Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs). Each of these organizations requires specific information that must be included in the documentation for reimbursement to occur. Individual facilities (e.g., hospitals, clinics, home health agencies, skilled nursing facilities) design documentation forms to meet their specific needs and to ensure that the information necessary for reimbursement is included. Billing systems may also influence the type of documentation format that is used in a particular setting.

Medicare is a major payer source in the geriatric physical disability setting. Medicare is a national insurance program and as such has set national standards for documentation. This government agency has put forth detailed guidelines stating expectations for what information must be included in the medical record to justify the need for occupational therapy services. Intermediaries will reimburse occupational therapy services only if all of the requirements established by the Medicare guidelines and regulations have been met. The Medicare Benefit Policy Manual (www.cms.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15pdf) describes the key words and phrases medical reviewers are looking for when they review a claim for payment. Medicare requires that specific information is clearly documented for each part of the therapy process for therapy services to be reimbursed. Many other payers of therapy services in adult rehabilitation follow Medicare guidelines when establishing documentation policies for reimbursement.18 An understanding of these requirements is critical in ensuring reimbursement for services provided. The therapist working with Medicare clients must become familiar with these guidelines and regulations to prevent denial of services. Detailed information can be found at the Medicare Website.

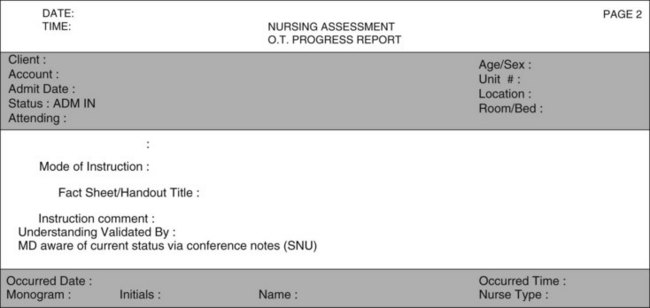

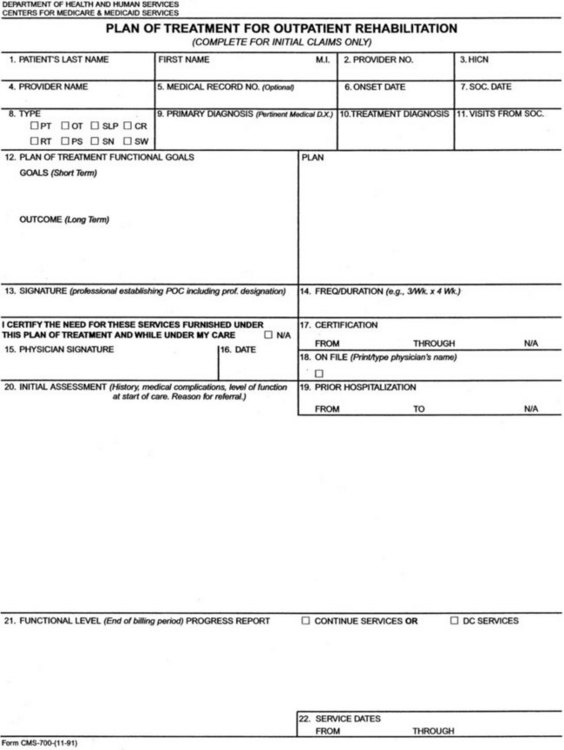

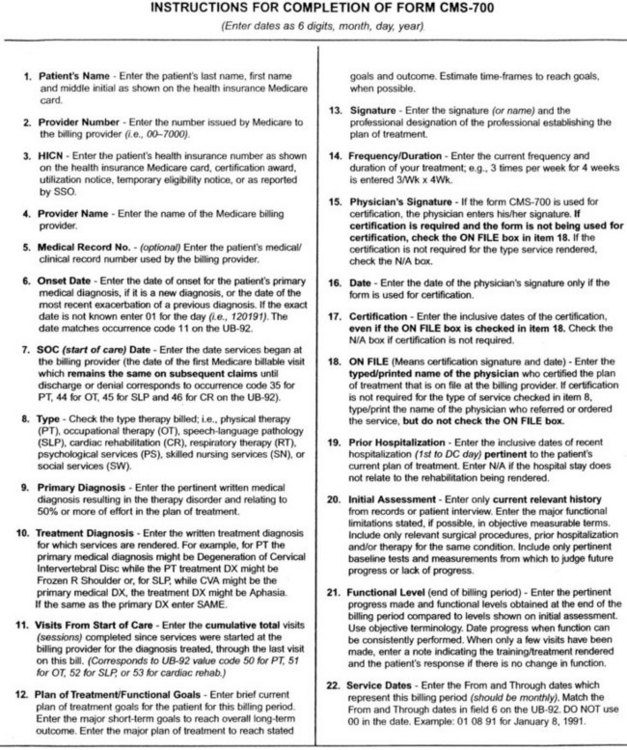

Although its exclusive use is no longer required, Medicare has designed a specific form for outpatient evaluations called the Medicare 700 form, the “Plan of Treatment for Outpatient Rehabilitation.” This form specifies the information required by Medicare. Figure 8-4 shows this form and directions for completing it. Documentation on the initial evaluation must demonstrate that it is reasonable and necessary for the therapist to complete the evaluation to determine whether restorative or maintenance services are appropriate. It is important to fill in all spaces on the 700 form. Failure to complete a section of the form could result in a technical denial. It is important to include a statement of the client’s prior level of function and the change in function that precipitated the occupational therapy referral. Results from assessments that support the need for therapy intervention are recorded in this section. Objective tests and measurements are used to establish baseline data. This information will serve as the basis for short- and long-term goals.

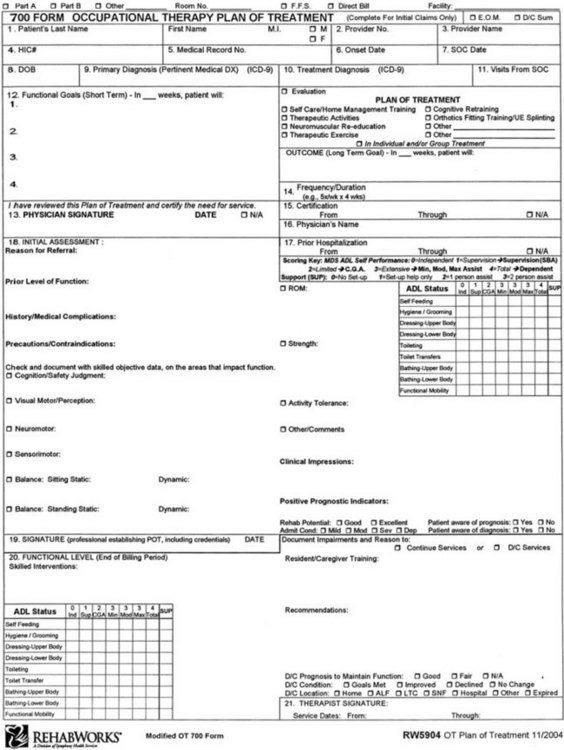

Many rehabilitation companies and hospitals have modified the 700 form with headings and checklists to assist the therapist in providing the type of information that will support the need for therapy services (Figure 8-5). Space on the 700 form is limited, and the therapist must be able to concisely present data that will clearly demonstrate the need for occupational therapy. A recent change in function (a decline or an improvement) is required to justify therapy. The plan of treatment (Section 12) includes functional, measurable goals based on assessment results as described in Section 18. Goals cannot address issues that do not have supporting baseline data in the Assessment section. The plan of treatment is the skilled intervention that the therapist will provide. The 700 form also functions as the end-of-month progress report and/or as the discharge form. Section 20 is completed at the end of the billing period. Progress, current functional status, and skilled interventions provided during the previous month are included here.

FIGURE 8-5 Modified Medicare 700 form—occupational therapy plan of treatment. (Courtesy RehabWorks, a Division of Symphony Rehabilitation, Hunt Valley, Md.)

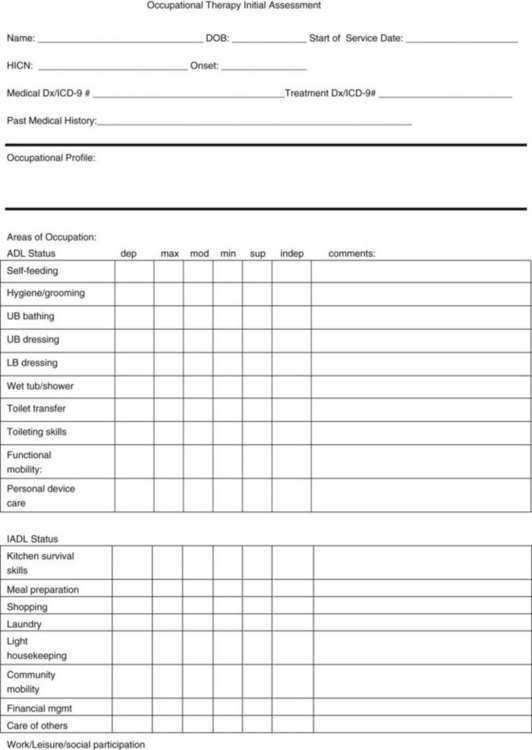

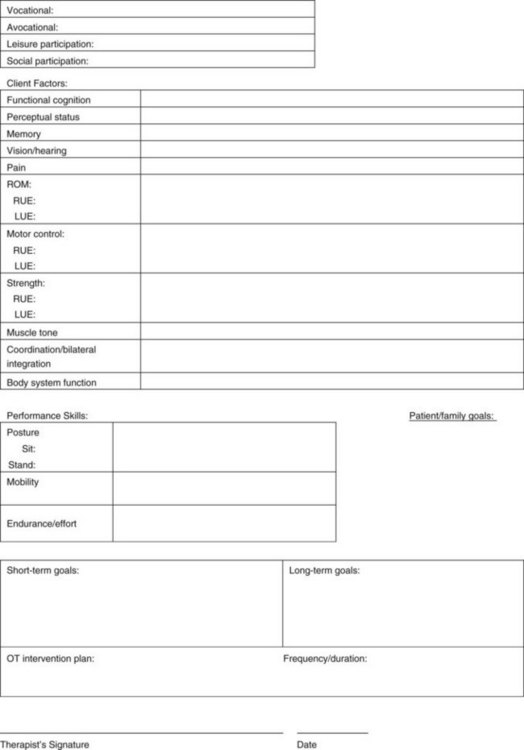

Figure 8-6 is an example of an initial evaluation form used in a rehabilitation center. It has been modified to meet the specific needs of the practice setting. Figure 8-7 shows an example of an occupational therapy evaluation report and initial intervention plan that incorporates the OTPF language and process. As facilities update evaluation forms, the OTPF language should be incorporated.

Confidentiality and Documentation

Maintaining confidentiality in documentation is the responsibility of the occupational therapist. Principle 3E of the AOTA Code of Ethics addresses the issue of privacy and confidentiality in all forms of communication, including documentation. “Occupational therapy personnel shall protect all privileged confidential forms of written, verbal, and electronic communication gained from educational, practice, research, and investigational activities unless otherwise mandated by local, state, or federal regulations.”3 Guidelines to the Code of Ethics2 speaks directly to confidentiality issues:

Information that is confidential must remain confidential. This information cannot be shared verbally, electronically, or in writing without appropriate consent. Information must be shared on a need-to-know basis only with those having primary responsibilities for decision making.

5.1 All occupational therapy personnel shall respect the confidential nature of information gained in any occupational therapy interaction.

5.3 Occupational therapy personnel shall take all due precautions to maintain the confidentiality of all verbal, written, and electronic, augmentative, and nonverbal communications (as required by HIPAA)2 (p. 655). Ethical practice demands that the therapist understand what is meant by confidential information and is knowledgeable about how to maintain client confidentiality. Information about clients, including their names, diagnoses, and intervention programs, cannot be discussed outside of the treatment environment. Client charts should not be removed from the facility. Reports containing personal information (name, social security number, medical diagnosis, etc.) cannot be left out in plain view, where others can read the information. Therapists, students, and staff cannot discuss clients in public areas where others may overhear the conversation.

Federal laws have been enacted to protect the consumer against breaches of confidentiality. The privacy sections of HIPAA clearly outline the expectations of health care professionals in issues of confidentiality. HIPAA was initially enacted in 1996 and consisted of a series of provisions that required the Department of Health and Human Services to adhere to national standards for electronic transmission of health care information. The law also required that health care providers adopt privacy and security standards by which to protect confidential medical information of patients. Beginning in April 2003, health care providers were required to adhere to the privacy standards mandated by HIPAA. Individually identifiable health information, also known as protected health information (PHI), is federally protected under HIPAA regulations. PHI is health information that relates to a past, present, or future physical or mental health condition. This rule limits the use and disclosure of PHI to the minimum necessary to carry out the intended purpose. It also gives patients the right to access their medical records. This regulation protects the medical records of clients, whether the information is written or electronic (computer) or is verbally communicated. Violations of the HIPAA rulings are subject to criminal or civil sanctions.9

The law requires that all staff be trained in HIPAA policies and procedures and understand the implications specific to the work setting. In addition to the client confidentiality procedures explained earlier, safeguards must now be adhered to for compliance with HIPAA regulations. The therapist has a responsibility to protect confidential information from unauthorized access, use, or disclosure. This includes information documented in the medical record. Papers, reports, and forms containing PHI should not be disposed of in the regular trash. Instead they must be shredded. Never leave medical records or portions of records (i.e., therapy notes) unattended in public view. Information (written, verbal, or electronic) cannot be shared with family members unless permission has been provided in writing by the client.

If documentation is done electronically, special care must be taken to prevent unauthorized persons from accessing client information. Log-in pass codes cannot be shared among staff. Therapists must take care to ensure privacy when entering information.

Summary

Documentation is a necessary part of the occupational therapy process. The occupational therapist has a responsibility to the client, to the employer, and to the profession to develop the skills that will allow him/her to accurately document the therapy process. Well-written documentation promotes the profession by providing proof of the value of occupational therapy intervention. It can provide valuable information for outcome research and evidence-based practice. It is a professional expectation that the occupational therapist will keep current on documentation requirements for his/her practice area and will acquire the skills necessary to accurately document the occupational therapy process.

References

1. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Guidelines for documentation of occupational therapy. Bethesda, Md: American Occupational Therapy Association; 2008.

2. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Guidelines to the occupational therapy code of ethics. Am J Occup Ther. 2006;60:652–658.

3. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Occupational therapy code of ethics. Am J Occup Ther. 2010:64.

4. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process ed 2. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62:625–683.

5. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Standards of practice for occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64:415–420.

6. Atler, K. Using the fieldwork performance evaluation forms: the complete guide. Bethesda, Md: American Occupational Therapy Association; 2003.

7. Borcherding, S. Documentation manual for writing SOAP notes in occupational therapy, ed 2. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2005.

8. College of St. Catherine. Goal writing: documenting outcomes (handout). St Paul, Minn: College of St. Catherine; 2001.

9. Fremgen, B. Medical law and ethics, ed 3. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2009.

10. Herz, NB, Bondoc, S. Electronic documentation: a conversation about alternatives, Administration and Management Special Interest Section Quarterly. American Occupational Therapy Association. 2007;23:1–4.

11. Hooper, B. Therapists’ assumptions as a dimension of professional reasoning. In: Schell B, Schell J, eds. Clinical and professional reasoning in occupational therapy. Baltimore, Md: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

12. Kettenbach, G. Writing SOAP notes, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2004.

13. Lloyd, LS. Documenting for patients and payers. www.aota.org/pubs/OTP/1997-2007/Columns/CapitalBriefing, 2004. [OT practice online. Available at].

14. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual. Covered medical and other health services. http://www.cms.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf, 2009. [Available at].

15. Meyer, MJ, Schiff, M. HIPAA: the questions you didn’t know to ask. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2004.

16. Quinn, L, Gordon, J. Documentation for rehabilitation. St Louis, Mo: Elsevier; 2010.

17. Perinchief, JM. Documentation and management of occupational therapy services. In: Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Schell BAB, eds. Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:897.

18. Sames, KM. Documenting occupational therapy practice, ed 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2010.

19. Schell, BAB. Clinical reasoning: the basis of practice. In Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Schell BAB, eds.: Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, ed 11, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

20. Weed, LL. Medical records, medical education and patient care. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1971.