Sexuality and Physical Dysfunction

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Justify sexuality as a concern of the occupational therapist.

2 List at least five possible reactions of the person with physical disability to her or his sexuality.

3 List some attitudes and assumptions that the able-bodied population may make about the sexuality of people with physical disability.

4 Discuss how sexuality and sensuality are related to self-esteem and a sense of attractiveness.

5 Define sexual harassment and describe how to handle a situation in which clients harass staff members.

6 Describe the effects that such items as mobility aids and splints can have on sexuality.

7 List signs of potential sexual abuse of adults.

8 List at least two intervention goals designed to improve sexual functioning.

9 Discuss ways in which the occupational therapist can provide a safe environment for discussing sexual issues.

10 Describe how sexual values can be communicated.

11 List at least five effects that physical dysfunction can have on sexual functioning and possible solutions for each.

12 Discuss the potential hazards of birth control.

13 List the potential complications of pregnancy and childbirth for a woman with disability.

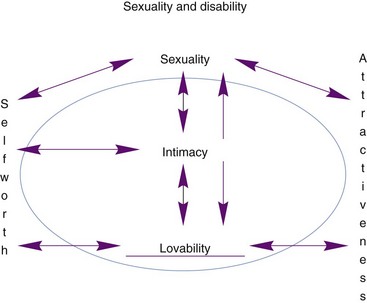

Sensuality and sexuality are important aspects of everyone’s activities of daily living (ADLs) and directly relate to the quality of each person’s life. As an ADL, sexual activity is in the domain of occupational therapy (OT).60 Occupational therapists work with clients in all areas related to sensuality and sexuality (Box 12-1). Sexuality is an integral part of the human experience and is important for self-esteem and self-concept. It includes emotions, feelings, and hopes for the future. Individuals express sexuality in different ways. Sexual expression is not only the sexual act of intercourse but may include talking, touching, hugging, kissing, or fantasizing. Engagement in sexual activities does not always take priority when individuals exhibit so many other problems and deficits related to their disabling condition (Figure 12-1).

Physical limitations may cause the client to question his or her ability to experience sexual pleasure. With the onset of physical disability, the client undergoes a significant change in the commonly held roles and practices of the able-bodied population.10,54,65 The individual with a disability may be regarded by able-bodied persons as asexual, or hypersexual, an object of pity, and unattractive.3,37,41 Being perceived as unattractive and possibly unlovable can cause the client to believe that he or she can never be intimate with anyone. Holding this belief can lead the client and related others to a sense of despair. McCabe and Taleporos44 found that “people with more severe physical impairments experienced significantly lower levels of sexual esteem and sexual satisfaction and significantly higher levels of sexual depression than people who had mild impairments or who did not report having a physical impairment.”

Low and Zubir41 and Kettl, Zarefoss, Jacoby, et al.35 found that females with acquired spinal cord injuries reported feeling less than half as attractive after they had acquired the disability, even though spinal cord injury is a disability with little observable physical change in body appearance. These studies showed a major decrease in the self-perception of attractiveness.41 Another study found that with the advent of a disability, males felt a loss of their sense of masculinity and sensed a threat to the male role.53

These are just a few examples of the feelings and perceptions that affect the sensuality and sexuality of the person who has a physical disability. To accomplish comprehensive rehabilitation with the client, the OT and other health professionals must address self-perception, beliefs, and needs related to sexuality. This chapter examines issues related to sexuality and sensuality with physical disability.

Reactions to Sexuality and Disability

The many obstacles encountered by people with disability should not interfere with the expression of sensuous and sexual needs. As an informed professional, each therapist can help the adult client eliminate unnecessary obstacles, overcome anxieties, and appreciate personal uniqueness. The expression of sexuality or sensuality is a sign of self-confidence, self-validation, and a sense of being lovable. When a person acquires a disability or is born with a disability, he or she can feel less positive about him or herself and less lovable.20,52,53

Sexuality can symbolize how a person is dealing with the world. If a person feels inadequate as a sexual, sensual, and lovable human being, the motivation to pursue other avenues of life can be affected. When an individual has a negative self-image, coping with life’s problems is difficult. Because sexuality is often used as a barometer of how one feels about oneself, it is productive for the therapist to help the client feel as positive as possible about her or his physical and personal qualities. A healthy attitude toward one’s sexuality enhances motivation for all aspects of therapy. The therapist must try to help the client adjust self-perceptions enough to function positively in life.

Sexuality has been found to be a predictor of marital satisfaction, adjustment to physical disability, and success of vocational training. In society, people are often judged by physical attractiveness.54 In Western civilization, physical intimacy is closely associated with love. Therefore, if a person perceives himself or herself as incapable of expressing sensuality or sexuality, it is possible that he or she feels incapable of loving and being loved. The majority of people who have had a stroke “reported a marked decline in all measured sexual functions.”24,36 Without the capability of loving and being loved, a sense of isolation and of being valueless may ensue.6,41,48,52 Adaptive devices such as splints, wheelchairs, and communication aids can be a detriment to one’s perceived attractiveness and sexuality. For example, it may be hard to perceive of oneself as sexual when an indwelling catheter is present or when splints are worn. By discussing the effects of these devices on social interaction, the client can get some ideas about how to handle difficult situations when they arise.1,40,48,67

OT intervention should include goals that facilitate an increase in self-esteem and enable the client to feel lovable. The therapist’s role is to foster feelings of self-worth and a positive body image to help the client engage in occupations and to minimize feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness.6,21,41,52,54 Feeling lovable engenders a sense of self-worth, attractiveness, sensuality, sexuality, and being capable of intimacy. Achieving this goal enhances the development of a healthy and realistic life balance (Figure 12-1) in which the client engages in occupations.

Whether sex is still possible is a concern that arises after the onset of physical disability. This concern is often set aside in the immediacy of coping with the adjustment to hospital life and activities that make up the daily routine. However, the concern is not forgotten. A common complaint made about members of the health care team by people with disabilities is that the staff members do not readily bring up the subject of sexuality and it’s not an integral part of the rehabilitation process, treatment plan, or medical appointment. Individuals with disabilities feel that if their sensuality and sexuality are often negated, a significant facet of their personhood is negated. This lack of acceptance causes the person with a disability to lose the feeling that he or she is treated as a whole person. Currently no single health care profession has been designated to address issues concerning the physiological and psychosocial changes related to sexuality following an injury or illness; rather, interdisciplinary team approaches are often used. However, when a single discipline is not designated, then the subject may be left unaddressed.65

Often men and women with disabilities have an increased dependence on an able-bodied partner, which results in a decrease in their sex life.18 One possible explanation is that the able-bodied partner is less inclined to be aroused when he or she has just bathed the partner or assisted the partner with toileting. It is often difficult to transition from caregiver to intimate partner. The therapist must be sensitive to the possibility of these perceptions and help the client deal appropriately with the feelings they evoke.

The client’s sense of masculinity or femininity may be threatened by the disability.42,53,56 Men who have recently acquired a disability report that they feel emasculated.53,56 Feelings of emasculation can be reinforced by physical limitations. For example, lifting weights may no longer be possible, sports participation may not be possible without adaptations, and attendance at sporting events may be limited by lack of access. The necessity to look up at others from a wheelchair and ask for assistance can engender feelings of dependency.

A man with a disability may react to feelings of dependency and emasculation53 by flirting to prove his masculinity. The client may attempt to flirt or make passes at a therapist. Because it is estimated that up to 10% of the population is homosexual,22,49 the therapist can expect that at some time clients of the same sex may make sexual advances.

Women experience many of the same feelings but probably interpret and react to them in a different way.5 Women with disabilities report feeling unattractive and undesirable. This can lead to despair if a woman feels that she cannot achieve some of her major goals in life. Thus, the female client may flirt to see if she is still attractive to others.

The therapist must realize that the client is seeking confirmation of her or his sexuality. The therapist should not be surprised by flirtations or sexual advances from clients. In response, the OT practitioner should deal with these behaviors and set therapeutic boundaries in a positive and professional manner, but the therapist should not be harassed. All of the therapist’s interactions should be directed toward creating an environment that promotes the client’s self-esteem, positive and appropriate sexuality, and adjustment to disability.

Inappropriate sexual advances, sexual harassment, or exploitation of either the therapist or the client cannot be permitted.45,59 Behavior is considered harassment when it causes the therapist to feel threatened, intimidated, or treated as a sexual object. If sexual harassment is allowed, it can be damaging to the client and to staff morale.27 The therapist should provide direct feedback explaining that he or she feels offended and that the behavior is inappropriate and must cease. All of the staff members should be informed and develop and implement a plan to modify the client’s behavior if it persists.

Therapeutic Communication

Conversations regarding sexuality can be opportunities for discussing personal feelings and perceptions. One way to approach discussion of intimate matters is by asking the female client how she will perform breast self-examination with her disability. A male client can be asked how he will perform self-examination of the testicles. If the treatment facility does not have information about these examinations, the client can obtain them from the American Cancer Society or the local Planned Parenthood Association. Each of these activities falls into the domain of health maintenance and may not have been discussed by other health team members. This interaction will set the stage for discussion of other personal matters, impress upon the client the necessity for concern about personal health, and reaffirm the client’s sexual identity.

Clients often feel safe asking the OT about sexual matters related to their disabilities, because the therapist deals with other intimate activities such as bathing, dressing, and toileting. It is also important to discuss sexual hygiene as an ADL. The trust built up in the relationship encourages this communication. The therapist should be prepared with information and resources. The therapist does not need to know everything or be a sex counselor but should see that the client gets the necessary information or referral.

The OT is the most appropriate professional to solve some problems, such as motor performance needed for sexual activity.12 For example, discussing positioning to reduce pain or hypertonicity or to enable the client to more comfortably engage in sexual relations will help the client deal with problems before they occur.15,38,48

Shivani, who has hypertonicity, particularly in hip adductors, experiences discomfort in a sexual position in which she abducts her legs during intercourse with her husband. She and her husband have not explored other positions but instead have decreased the number of times they have intercourse during the month. Shivani’s sense of failure and feelings of diminished worth as a wife have further affected the intimacy of her marriage.

Approaches to intervention can include individual, partner, or group sessions. The format in which the information is presented can also vary and is dependent on where the individual is physically, cognitively, and emotionally. It is important to provide the information in a way that can be best understood and when the individual is ready to assimilate it. Information can be presented in many ways and may include diverse media such as videos, pamphlets, or booklets. Varied media may be used to address the unique learning style and need of the individual.8

During all aspects of the rehabilitation process, the client needs to work on communication with the therapist, staff, and his or her sexual partner. The therapist can facilitate this process simply by giving the client permission to discuss feelings and potential problems, especially sexual problems. The client needs to learn how to accurately communicate sexual needs, desires, and position options to a partner, either verbally or nonverbally, to have a mutually satisfactory sexual relationship.19,35 Each client will have unique problems or issues that are related to the nature of the disability. An example is a client with Parkinson’s disease in whom the lack of facial expression impedes the nonverbal communication of intimacy. The client can be taught to communicate feelings verbally that were previously conveyed with facial expressions.

Values Clarification

Sexual values of the client, the partner, and the therapist must be examined for the therapist to interact with the client in the most effective and positive manner.3,17,42,48,54 Many professional schools do not train health care workers on the subject of sexuality and disability.3,26,56,61 In-service training can be arranged to help the staff be aware of the sexual needs of people with disability.23,35 Books, articles, videos, training packets, and online Internet resources are available for professional education.9,16,17,56 Sensitivity training for staff is imperative in creating an atmosphere of openness to discussing issues of sexuality. The sexual attitude reassessment seminar (SARS)28 uses lectures, media, and small group discussions to help participants explore their knowledge and beliefs about sexuality. This seminar also describes sexual problems, how they develop, and how education and therapy can help with their clients. At the very least, it’s helpful for therapists to participate in available in-services and role playing in order to increase knowledge and comfort in dealing with questions about sexuality from patients and families.

Unless the staff members are educated about the significance of sexuality and related issues, they could have negative feelings about dealing with these matters.3,9,61,66 If the therapist is not aware of the thoughts and feelings of all of the individuals involved, the therapist could make incorrect assumptions that have negative results.15 One of the most direct ways of gaining information is by taking a sexual history.15,56,57 The purpose of a sexual history is to learn how a person thinks and feels about sex and bodily functions and to discover the needs of those concerned.15,39,56 According to some researchers, many individuals with a disability had a sexual dysfunction before they acquired the physical disability. Taking the sexual history can help to identify such a problem.40

Sexual History

When taking a sexual history, the therapist should create an environment that will allow for confidentiality, comfort, and self-expression. In early intervention, the therapist should ask about the client’s concerns regarding contraception, safe sex, homosexuality, masturbation, sexual health, aging, menopause, and physical changes.

Box 12-2 lists some questions that could be asked. All questions should not be asked at the same time, nor would all questions be asked of every client.

After taking the sexual history, the therapist can often ascertain whether guilt is connected with the sex act, body parts, or sexual alternatives (such as masturbation, oral sex, sexual positions, or sexual devices). For example, some clients report feelings of guilt or fear in relation to having sex after a heart attack or a stroke—fear that sex can cause a stroke or guilt that it may have caused the first episode. Another fear is that the partner will not accept the presence of catheters, adaptive equipment, or scars. Performance is often an issue. Able-bodied persons and those with disabilities ask questions regarding the sexual ability of the person with disabilities.

The therapist can furnish the necessary information by (1) directing the client to other professionals, (2) providing magazines and books that discuss the subject, (3) showing movies, or (4) suggesting role models. The therapist must be tactful and remember that the client is probably questioning her or his own values and previous notions about sexuality. Personal care such as toileting, personal hygiene, menstrual hygiene, bathing, and birth control are issues that can evoke reflection on values regarding sex and body image.

Self-care issues, particularly personal hygiene and sexuality, usually are not emphasized enough during acute illness and rehabilitation. Discussing such issues once or twice is not sufficient. The circumstances and environment in which these issues are discussed should also be considered. The therapist must create an environment that will allow personal discussions to occur. A personal conversation cannot take place in a crowded therapy room, during a rushed and impersonal treatment session, or with a therapist with whom a good personal rapport does not exist. Building rapport is a problem in health care facilities in which therapists are frequently rotated or work on a per diem basis.

A discussion of feelings will also help the client explore her or his new body or adapt to ongoing degeneration of the body if there is a progressive disability. These conversations may take place while other therapeutic activities are in progress so that billing insurers for time is not a barrier.

Sexual Abuse

The sexual abuse of adults with disabilities is a considerable problem.1,58,61,66 Clients should be made aware of the possibility of exploitation, especially when using the Internet for social networking and online dating sites. Others have reported that medical staff members took inappropriate liberties with them and that personal care attendants, on whom they depended, demanded sexual favors. Clients can and should report such abuse to Adult Protective Services. The therapist also must report cases of suspected sexual abuse. The client may be reluctant to report abuse because of a concern that it will not be possible to get another aide or that, during the time it takes to hire another aide, essential assistance will not be available. These are major problems for a person who is dependent on others for care.

Therapists usually do not suspect caregivers, medical staff, aides, transportation assistants, or volunteers of sexual abuse, but the therapist should be alert to signs of possible abuse even from these sources.55 Some individuals prey on adults and children with disabilities and are drawn to the health fields with this motive.1 The therapist should watch for signs of potential abuse, such as clients usually being upset after interacting with a specific person, caregivers taking clients off alone for no apparent reason, excessive touching in a sensual manner by caregivers, the client being agitated when around a particular individual, and the client being overly compliant with a specific individual.

The therapy session should help the client develop a sense of personal ownership of her or his body. This goal may be neglected when working with adults and is often neglected in working with children. For example, a child who believes that he or she does not have the right to say no to being touched, who cannot physically resist unwanted advances, and who may not be able to communicate that abuse has taken place is in jeopardy for being a victim.1

The therapist should ask permission before touching the client and should touch with respect and maintain the client’s sense of dignity. If the therapist does not ask permission to touch a client, the client can lose the sense of control over being touched by others. The therapist should guard against communicating this notion to the client.

Naming body parts and body processes is a good way of helping clients take charge of their bodies. Once the body parts and processes are named, using correct terminology rather than slang, the possibility exists for the client to communicate and to relate in an appropriate manner.1,14,47,57 The use of the proper terms has the effect of helping the client view the body in a more positive way, whereas slang tends to communicate negative images.57

Effects of Physical Dysfunction

Specific physical problems that may create difficulties in sexual performance for people with disabilities and their partners and suggestions for management of the problems are outlined next and summarized in Table 12-1.

Hypertonia

Hypertonia can increase when muscles are quickly stretched. To prevent quick stretching of muscles involved in a movement pattern, motion should be performed slowly. It is advisable to incorporate rotation into the movement to break up the tone. Slow rocking can be used to inhibit hypertonic musculature. Gentle shaking or slow stroking (massage) can also be inhibitory. Heat or cold can also be used to inhibit tone. Clients with hypertonia should review options for different positions in which to have sexual intercourse. Alternative ways of dealing with personal hygiene (e.g., toileting, inserting tampons, gynecologic examinations, and birth control) may also need to be explored in relation to hypertonicity.

Shivani’s OT discussed strategies that could be used to relax the hypertonicity in her legs, such as gently rocking her legs side to side while she was seated. Although initially presented as a means to decrease the hypertonicity affecting Shivani’s sitting balance when toileting and for personal hygiene during menstruation, this technique also was suggested as a means to relax her legs before intercourse.

Hypotonia

Clients with low muscle tone (hypotonia) need physical support during sexual activity. Pillows, wedges, or bolsters may be used to support body parts, allowing for endurance and protecting the body from overstretching and fatigue. Sexual positions that allow support of the joints involved should be explored. The client and her or his partner should also explore their attitudes about the positions.

Low Endurance

Prolonged sexual activity can be intolerable because of low physical endurance. Some techniques for dealing with low endurance are employing principles of work simplification to sexual activity, using timing to engage in sex when the client has the most energy, and assuming positions in which sexual performance uses less energy.

Loss of Mobility and Contractures

Limited mobility and contractures prohibit many movement patterns and limit the number of positions for sex. Activity analysis must be done to find positions that will allow sexual activity. This system often requires creative problem solving on the part of the client, the partner, and the responsible professional counselor.

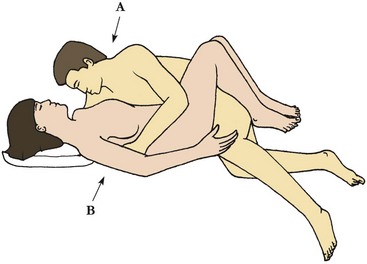

Joint Degeneration

Conditions such as arthritis can cause pain, damage to the joints, and contractures. Avoiding stress and repetitive weight bearing on the joints can decrease joint damage. Activity analysis is needed to reduce joint stress and excessive weight bearing on the joints. It is necessary to find a position, such as that shown in Figure 12-2, that takes weight and stress off the knees or hips. This position is sometimes referred to as the missionary position. A position with substantial hip abduction may not be acceptable for the client, in which case a side-lying position may be more acceptable. If hip abduction is limited, the woman should avoid positions such as those shown in Figures 12-2 as well as Figures 12-5 and 12-9, presented later in the chapter. After Shivani’s OT introduced the technique of slow rocking, Shivani asked about other positions that would be more comfortable during intercourse. The OT discussed the possibility of using the side-lying position to decrease the stress on the hip joints and discomfort Shivani experiences during intercourse.

Pain

Pain limits the enjoyment of sexual activities.31 Usually at some time of day pain is diminished and energy is at its highest. Sexual activities can be scheduled for such times. After pain medication has taken effect, many people find that sexual activity is possible. Communication between partners is especially important when pain is involved. An unaffected partner who does not understand the negative effects of pain may believe that the affected partner is not considering her or his personal needs. A referral to a counselor who understands the effects of pain or to a pain specialist can help work out emotional and physical aspects of this problem. The OT can help the client think of acceptable ways of meeting the partner’s sexual needs without causing pain. Masturbation and mutual masturbation with sexual fantasy are possible ways of meeting sexual needs in these circumstances. In this way the partners are interacting and neither person feels isolated.

Loss of Sensation

The loss of sensation can affect the sexual relationship in several ways. The lack of erogenous sensation in the affected area can block proper warning that an area is being abraded (e.g., the vagina not being sufficiently lubricated) or damaged (e.g., bladder or even bones if the partner is on top and being too forceful). A lack of sensation may be a sign of disruption of the reflex loop responsible for sensation and erections in the male and sensation and lubrication in the female.

Cognitive Impairments

Disabilities such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), multiple sclerosis (MS), and cerebrovascular accident (CVA) may affect sexual relationships and sex drive. Clients may exhibit difficulties with attention/concentration, social communication, decreased awareness, and executive functions such abstract thinking, all of which can affect relationships and successful sexual interactions.7

Aging and Sexuality

With aging, changes take place that can affect sexuality. Menopause and the resulting hormonal changes cause vaginal atrophy in women and slower reactions to sexual stimulation. In the male, greater stimulation may be needed to develop and maintain an erection, and reaction time between erections may be greater. Partners can be informed of ways to increase stimulation and can be helped to understand that it is the quality, not the quantity, of sexual activity that is important in the relationship. The client should be made aware of the maturation process and its normal effect on sexuality so that the disability is not blamed for all of the problems.

Isolation

The environment is composed of objects, persons, and events. In all activities is an interaction between the person and environment. Some of the objects with which people with disabilities interact are wheelchairs, braces, canes, crutches, and splints. These objects are all hard, cold, and angular. They can communicate a hard exterior and a fragile interior and can convey the notion that no softness exists, that it is not safe to hug, and that a person in a wheelchair or in braces or on crutches can get hurt or toppled if touched. As a result of these ideas, the individual with a disability may feel isolated by the appliances.

Some people tend to withdraw from the objects around the client. This may reinforce the client’s notion of a lack of sensuousness and increase the client’s sense of isolation. Clients often feel isolated and different from the “normal” population.17 This phenomenon is more common among clients who have been out of the health care facility for a period of time. In the early phases of the disability, the therapist and the client can role-play about how to deal with a new partner or how to explain the equipment used, such as a catheter. This approach may help ease the client’s fears and increase the client’s comfort with such issues. At the same time, the therapist is communicating that sex may be a possibility in the future. It should be pointed out to clients that at no time in human history have people with disabilities not existed in society, that they are a part of society, and that it is not “abnormal” to have disability. All people who live long enough will acquire a disability to a greater or lesser extent at some time.

Medication

Approximately 20% of individuals experience various side effects from prescription medications. Potential side effects of medication are impotence, delayed sexual response, or other problems. Diuretics and antihypertensives can cause impotence, decreased libido, and loss of orgasm. Tranquilizers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and antidepressants can contribute to decreased libido and even impotence in some individuals.56 Side effects of medication should be discussed with the physician and the pharmacist to see whether medications can be altered or changed. If they cannot, acknowledging that the problem is organic can be helpful to the client.

Street drugs also have sexual side effects and adversely affect sex drive and desire. For example, methamphetamines and cocaine may have the sexual side effect of decreased interest in sex and difficulty reaching organisms. Marijuana and alcohol can cause difficulty in obtaining and sustaining erections. Although occupational therapists do not condone usage of street drugs, it is important to consider that it may be part of our client’s life and providing education on these side effects is critical.

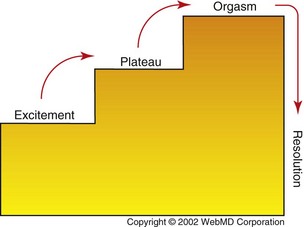

Performance Anxiety

At times of great emotional stress, a male client may find that the erection is inhibited. This problem can lead to increased anxiety in relation to sexuality and create a cycle of dysfunctional inhibition. It can be helpful for the client and his partner to take the focus off erection and genital intercourse and focus on sensuality and making each other feel good. A massage is one possibility that will allow for more normal physiological reactions. If this approach does not work, a trained counselor may be needed to help the couple deal with the problem, if it has been determined that the problem is not organic in nature.

Skin Care

The person with a disability should be informed that positioning modifications might be needed to protect the skin, prevent skin breakdown, and increase pleasure. If a sexual position causes repeated rubbing on the skin, this friction can cause abrasions and result in skin damage. The therapist and client can discuss methods to prevent the friction—through an alternative position, for example. Pressure on bony prominences or pressure exerted in a specific area by a partner can also cause problems with skin irritation and must be avoided.

Lubrication

Stimulating natural lubrication in female clients is important. It may be overlooked in a woman with paralysis because she may not be able to feel the stimulation or lack of natural lubrication. Stimulation to cause reflexive lubrication should occur even when the woman does not feel it. Without proper lubrication, damage may occur without awareness of the problem. If needed, artificial water-based lubricants (such as K-Y Jelly) should be introduced. The individual should be warned that only water-based lubricants are appropriate because petroleum-based lubricants can cause irritation and can attack latex condoms, causing condom failure. This is a major concern because the female partner is more likely than the male to become infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in any given heterosexual encounter.

Erection

Many men regard the ability to achieve an erection as one of the most significant signs of masculinity.39 If awareness of sensory stimulation to the penis is blocked by the sensory loss associated with paralysis and if the male client does not try to stimulate a reflexogenic erection, he may believe that he is impotent. This is not necessarily true, and the client may go through much needless anguish. The client should be encouraged to explore his body. Rubbing the penis, the thighs, or the anus can be effective ways to evoke a reflexogenic erection. Even rubbing the big toe has been reported by some men with quadriplegia to stimulate an erection. If the normal reflex arc is interrupted, it is usually not possible to achieve an erection, and alternative methods must be explored.

Alternative methods can be forms of sex that do not require an erect penis, such as using a vibrator or trying oral or digital sex. If the client feels that penile intercourse is the only acceptable method, other possibilities do exist.13 Injections of hormones that stimulate erections can be used, but this practice may have adverse reactions or lead to problems if the client does not have good judgment or lacks hand dexterity. The use of a vibrator or massager against the penis to help produce ejaculate is sometimes effective and is one of the less invasive techniques.57 Surgical implants can be used but have disadvantages, such as the possibility of infection and skin breakdown. With a physician’s prescription Viagra, Levitra, and Cialis are among the stimulants that are being developed and may be a possibility for some clients but have some major side effects.

Fertility

Some disabilities may directly impact an individual’s ability to biologically become a parent. For example, women who sustain a spinal cord injury (SCI) or traumatic brain injury (TBI) may experience a disruption in their menstrual cycle. This pause may last as long as 6 months after an injury. However, the ability for a woman to have children is not usually affected once her menstruation resumes. It should be noted that depending on the disability, a women may be subject to certain pregnancy-related complications, and those should be discussed with a physician prior to considering pregnancy. Men with catastrophic injuries or illnesses such as spinal cord injury also experience difficulty with fertility. Typically, the reason for this is the inability to ejaculate during intercourse. Men who wish to father a child do have options, and a fertility specialist should be consulted.

Birth Control

The client should consult with her or his physician in weighing the pros and cons of various methods of birth control. People with disabilities must consider a number of factors when planning birth control.12,13,29,38,47 Because most disabling conditions do not impair fertility (especially for women), it is important for the client to be aware of birth control and potential complications of the use of birth control.

Condoms require good use of the hands. An applicator can be adapted in some cases, but someone with good hand dexterity must assemble the device beforehand. Diaphragms are not very feasible for people who have poor hand function, unless the partner does have hand function and both parties feel comfortable about inserting the diaphragm as part of foreplay. The contraceptive sponge also requires good use of hands.

Using birth control pills can increase the risk of thrombosis, especially when the client is paralyzed or has impaired mobility. If the client has decreased sensation, the intrauterine device (IUD) can result in complications from bleeding, cramping, puncturing of the uterus, or infection. The use of spermicides requires good control of the hands or the assistance of the partner who has normal hand function. The use of nonoxynol 9 has been suspected to increase the risk of HIV transmission and should be avoided.50 The injectable type of birth control may allow for easy use but has many of the same side effects as the pill. In using any method of birth control, the client must always be concerned with decreasing the chance of infection and with practicing safe sex.

Adaptive Aids

Adaptive aids may be necessary, especially if the client lacks hand function. One aid is a vibrator for foreplay or masturbation.25 Special devices have been adapted for men and women.15,38,47 Pillows may be used for positioning, and other equipment may be used for clients who have special needs. The therapist must prepare the client for the concept of using sexual aids before suggesting the option to the client. For example, the therapist can suggest that the client privately explore the sensation that the vibrator produces in the lower extremities. The client might discover the possible use of the vibrator for sexual stimulation or at least, when told how it can be used, may be more open to the idea of using a vibrator as a sexual aid.

Safe Sex

The issue of safe sex has increased considerably since the advent of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Safe sex is important to protect against all forms of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).29 Clients need to be advised that this is an important issue. If there is a sensory impairment in and around the genital area, the person might not be aware of an abrasion or infection. Having any genital irritation or infection allows easy entrance for STDs. The person with disability must be informed of the increased risk for HIV and STDs so that extra caution can be taken.

Hygiene

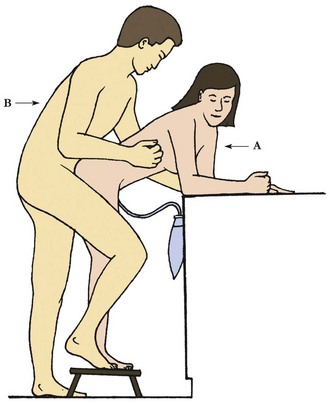

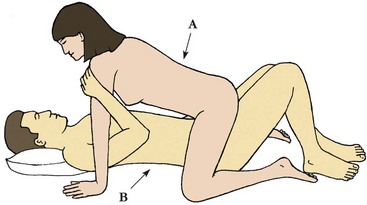

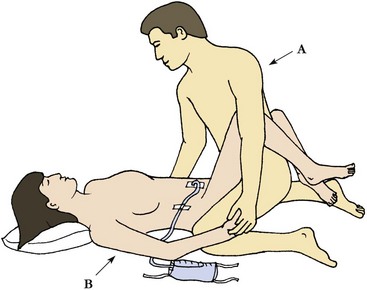

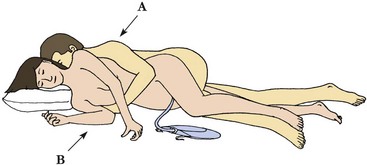

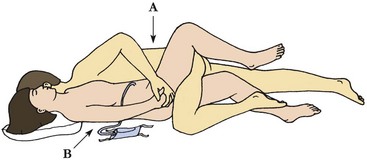

Catheter care is a concern, especially when hand function is impaired. Questions may be raised regarding how or if a person with an indwelling catheter can have sex. Sex is possible for both men and women, but some precautions should be taken. If the catheter becomes kinked or closed off (which will definitely happen in the case of a catheterized man having vaginal intercourse), pressure should not be placed on the bladder. The bladder should be fully voided before sexual activity. Urine flow should be restricted for as short a time as possible and no more than 30 minutes. Damage to the bladder and kidneys could result if these precautions are not followed. The client should not drink fluids for at least 2 hours before sex to prevent the bladder filling during this time. Sexual positions that avoid placing pressure on the bladder should be used (Figures 12-3 to 12-10). Many of the same positions can be used if the client uses a stoma appliance.

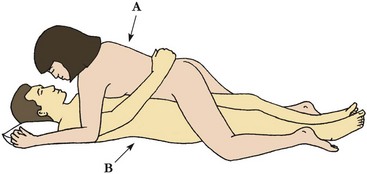

FIGURE 12-3 Vaginal entry of B requires no hip abduction, and hip flexion tightness would not impede performance. Energy requirements for both parties are minimal. Bladder pressure, catheter safety, and stoma appliance safety should not be an issue in this position for B. This position may be recommended if B has back pain or is paralyzed, especially if roll is used to support lumbar spine.

FIGURE 12-4 Partner A needs little hip abduction but good strength. Partner B may find decreased strain on his back. Hip, knee, or ankle joint degeneration would preclude this position for either partner.

FIGURE 12-5 Person A must have hip abduction, balance, and endurance but pressure is off of bladder and stoma. If a catheter is used, it would be unrestricted. Back pain may be avoided by keeping the trunk vertical. Person B’s hip flexors could be contracted. If low back pain is a problem, the legs should be flexed and the roll placed under low back. If the stoma appliance is used, this position would prevent interference. If low endurance is a problem, this position can be used effectively for B.

FIGURE 12-6 This position keeps pressure off the bladder, lessens the chance of tubing becoming bent, reduces pressure on the back (especially if a small roll is used under the low back), and does not require B to use much energy. The legs do not need to be as high as is shown, but if hip flexors are contracted, this position may be comfortable.

FIGURE 12-7 Partner B need not expend much energy in this position. Both partners may avoid swayback in this position. Either person may have hemiparesis. Person B will not need hip abduction, and pressure on the stoma bag may be avoided.

FIGURE 12-8 This position can be used if either partner has hemiparesis. If low endurance is a problem, this position can be used. Person A may avoid swayback in this position.

FIGURE 12-9 Partner B can be paralyzed or have limited range of motion. His back may need roll for support, and he must be concerned with pressure on his bladder.

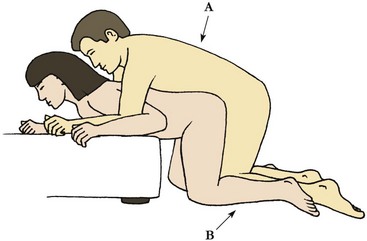

FIGURE 12-10 Rear vaginal entry of B, who does not need much energy because of support and little or no abduction of hips. Flexion tightness of hips does not affect performance. Because of the weight on B’s knees, hips, and back, as well as inevitable repetitive movement at hips, this would not be a good position for individuals with back, hip, or knee joint degeneration.

Women who have various disabling conditions have reported irregular menstrual periods and deterioration of their neurologic condition during menstruation.64 Hygiene issues may occur for several reasons. Lack of education, poor hand function, and poor sensation are conditions that may contribute to menses complications. Information regarding toxic shock syndrome should be given to clients who may not feel or be aware of infection. A sanitary napkin or pad requires less fine motor skill and is less dependent on intact sensation than a tampon. Although the client’s preferences must be considered, the therapist is responsible for educating a woman regarding the pros and cons of using either a sanitary pad or a tampon during menstruation. Menopause complications may be increased, but this area may need further research.

A person with an impairment of bowel or bladder function may have an occasional episode of incontinence during sexual activities. If the client and the therapist discuss this possibility and how to deal with it, some embarrassment can be averted when it occurs. The client and therapist can role-play to explore various scenarios, such as “You are planning intimacy with a new partner. How will you explain your catheter and appliances to the person?” These may be awkward conversations for the therapist and the client, but dealing with these issues beforehand is usually easier than waiting for the situation to arise. Such topics must be approached with caution and discretion.

Pregnancy, Delivery, and Childcare

Before becoming pregnant, women must weigh the risks and benefits of pregnancy, childbirth, and childcare. Complications of pregnancy may affect the client’s function and mobility. These include the potential for respiratory or kidney problems. The effect of the increased body weight on transfers, an increased possibility of autonomic dysreflexia, and the need for increased bladder and bowel care should all be considered when pregnancy is contemplated.63 Labor and delivery can present some special problems, such as a lack of awareness of the beginning of labor contractions. Induction of labor may be contraindicated if a person has a spinal cord injury at T6 or above and the medical staff members are not trained to deal with the respiratory problems or dysreflexia that can result. After delivery, the parent with disability will need to have modifications made to the wheelchair. The client may need consultations to achieve an optimal level of function in the parenting role.29

Using Shivani as an example, the therapist may help her with where to find information. Introducing her to sites appropriate for an online search, or encouraging her to contact Planned Parenthood or United Cerebral Palsy to gain the information to make informed decisions would help her locate necessary information. She could also ask these agencies for a list of doctors who have experience with women who were pregnant and have cerebral palsy.

The therapist may then simulate situations during the first year after birth. This may include how to transport an infant, change diapers and dress the child at different stages, play with the child, bathe the child, and deal with parenting when one has mobility impairments, just to name a few possible scenarios.

Sexual Surrogates

A sexual surrogate is someone trained to work with individuals to help them deal with sexual dysfunction or explore their sexuality. Typically a surrogate will work with a therapist and a client. A sexual surrogate will engage in sexual behaviors with the client, often using specific techniques that have been shown to be effective. The goal is to allow the client to explore aspects of sexual response, sexual feelings, and sexual techniques in a safe environment with a professional who is trained to provide feedback and offer advice.34 The main goal of the interaction is education.

Methods of Education

The following techniques or approaches have been used effectively to deal with the emotional aspects of sex education for people with disability.

Repeat Information

Mentioning sexual issues just once is not enough. Whether they have a disability or not, most people need to hear information more than once. This fact is especially true for people who are in crisis or who are in the process of adjustment to a disabling condition. Too much information, or more than is asked for, should not be offered at one time. Whenever possible, the therapist should try to say something positive in every conversation. Holding out hope for the restoration of function or alternative function is important. The therapist should not assume that the client understands all of the information. To verify that the information is understood, the therapist should invite the client to ask questions and to paraphrase what has been said.

Discovery of the “New” Body

With any disability, the client’s body image and perception of the body are altered. In effect, the client has a new body and must find altered ways of moving, interpreting sensations, and performing ADLs. A large part of the therapeutic experience is directed toward helping the client discover how to use this new body as effectively as possible. The therapist can facilitate this discovery of the new body by creating situations that encourage awareness of the body through the input of sensation and function.40 The client alone or with her or his sexual partner can accomplish this awareness through exercises that encourage exploration of the body. Exercises such as the gentle tapping or rubbing of a specific area can be developed to see if sensation exists or if the stimulation causes a change in muscle tone. Many people with a disability such as paralysis report that they have experienced nongenital orgasms12 by stimulating other new erogenous areas, often in the area just above where sensation starts to appear. The therapist may suggest ways to use this sensation or change in tone in ADLs or may ask the client to think of ways this change in tone could be used, such as triggering reflex leg extension to help with putting on pants. This discussion stimulates problem solving by the client.

PLISSIT

The acronym PLISSIT stands for permission, limited information, specific suggestions, and intensive therapy. PLISSIT is a progressive approach to guide the therapist in helping the client deal with sexual information.2 Permission refers to allowing the client to feel new feelings and experiment with new thoughts or ideas regarding sexual functioning. Limited information refers to explaining what effect the disability can have on sexual functioning. An explanation with great detail is not usually necessary early in the counseling process. The next level of information is providing specific suggestions. It may be in the therapist’s domain to give specific suggestions on dealing with specific problems that relate to the disability, such as positioning. This is the highest level of input the average occupational therapist should attempt without advanced education and training in sexual counseling. Intensive therapy should be reserved for the rare client who has an abnormal coping pattern in dealing with sexuality. An extensive counseling background is needed to provide intensive therapy.

Activity Analysis

To assess the client’s positioning needs, the therapist must analyze the demands of the particular activity. This analysis entails looking at the physical, psychological, social, cultural, and cognitive aspects of the client’s functioning. Activity analysis should be implemented using an objective and professional perspective. The therapist must realize that the sex act itself, if one exists, is only a small part of the act of making love and should be treated as just one more ADL that must be analyzed and with which the client needs professional assistance. The therapist must also remember that not all partners had sex on a daily, weekly, or even yearly basis before the onset of the disability. The therapist’s values and biases should not be imposed on the client. Same-sex partners, multiple partners, masturbation, or a preference for no sexual activities are some of the client’s practices that could evoke bias.

Basic Sex Education

Some clients need basic sex education if they didn’t have the information before the onset of disability (Box 12-3). Some clients may not have been informed because of the disability, or they may be misinformed about sexual practices.1,12,41,46 Research has shown that people with hearing impairments have substantially less information regarding sex than do those without hearing impairments.62 In one study of adolescents with congenital disabilities, it was found that they were misinformed or not informed about sexual issues and that they relied on health professionals and parents to keep them informed.4 Women who had not had sex before age 18 years may be less inclined to have sex later if they are not given sexual information.19,25,41

If the OT is not the one to educate the client or the client’s partner, the therapist should anticipate the need for information and have resources available for the client to acquire the information. It is not advisable to recommend only books about sexuality and people with disabilities. Such books are useful, but their focus on the disability may be discouraging to some. Books written for the able bodied, such as The Hite Report on Male Sexuality,33 The Hite Report,32 and How to Satisfy a Woman Every Time,30 can be helpful. These books will not only give the client an understanding of sex, but they will also show the client that he or she is normal, while minimizing the focus on the disability. Excellent books written for individuals with disabilities also can be recommended. Some of these are Choices: A Guide to Sexual Counseling with the Physically Disabled,47 Reproductive Issues for Persons with Physical Disabilities,29 The Sensuous Wheeler,51 Sexuality and the Person with Traumatic Brain Injury,27 Sex and Back Pain,31 Sexuality and Disabilities,42 Sexual Function in People with Disability and Chronic Illness,56 and Enabling Romance.38

Summary

This chapter began with the case of Shivani and examined some of the possible needs of people with disabilities that affect the ADLs of sexuality. This topic is a powerful one that the OT must deal with in a professional and sensitive manner. We have seen that Shivani can engage in sexual activity, become pregnant, and be a good parent. She may need assistance with finding the better positions to have sex, and she may learn to enjoy her body and sex even though she was abused. All of these issues may be within the role of the OT and should be dealt with to improve the quality of life for the client.

OTs are concerned with the sexuality of their clients because sexuality is related to self-esteem and influences the adjustment to disability and because sexual activity is an activity of daily living. As with other ADLs, a physical dysfunction can necessitate some change in the performance of sexual activities. Education, counseling, and activity analysis can be used to solve many common sexual problems confronted by persons with physical dysfunction.

OTs can provide information and referrals to clients who are concerned with sexual issues. Trained therapists can provide counseling. Issues of sexual function, sexual abuse, and values need to be considered in providing sex education and counseling. Through activity analysis and problem solving, physical limitations that affect sexual functioning can usually be managed. Various sexual practices, modes of sexual expression, and expressions of sensuality are possible. The client needs the opportunity to explore her or his needs and acceptable options to meet those needs. The OT is one of the members of the rehabilitation team who has something to offer the client in the area of rehabilitation and sexuality and sensuality.

1. List at least five areas related to sensuality or sexuality that are usually the concerns of the OT.

2. What are some common attitudes of the able-bodied population about the sexuality of persons with physical dysfunction?

3. How do these attitudes affect the disabled person’s perception of her or himself and attitudes toward his or her own sexuality?

4. How is sexuality related to self-esteem and a sense of attractiveness?

5. Describe some typical questions for taking a sexual history. How can these questions be used to clarify values about sexuality?

6. How do mobility aids and assistive devices affect sexual functioning? How can this concern be managed?

7. What are some signs of potential sexual abuse of adults?

8. What are some suggestions for dealing with the following physical symptoms during sexual activity: hypertonia, low endurance, joint degeneration, and loss of sensation?

9. List some medications that may cause sexual dysfunction.

10. Discuss some issues and precautions relative to birth control for the woman with a physical disability.

11. How is a catheter managed during sexual activity?

12. What are some potential problems in pregnancy, delivery, and childcare?

13. Discuss some techniques for educating a person about sexual issues.

14. How should sexual harassment of staff members by clients be handled?

References

1. Andrews, AB, Veronen, LJ. Sexual assault and people with disabilities. J Soc Work Hum Sex. 1993;8(2):137.

2. Annon, JS. The behavioral treatment of sexual problems, Honolulu, Enabling Systems, 1974;vol 1-2.

3. Becker, H, Stuifbergen, A, Tinkile, M. Reproductive health care experiences of women with physical disabilities: a qualitative study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(12 suppl 5):S26.

4. Berman, H, Harris, D, Enright, R, et al. Sexuality and the adolescent with a physical disability: understandings and misunderstandings. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1999;22(4):183.

5. Black, K, Sipski, ML, Strauss, SS. Sexual satisfaction and sexual drive in spinal cord injured women. J Spinal Cord Med. 1998;21(3):240.

6. Blum, RW. Sexual health contraceptive needs of adolescents with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(3):330–337.

7. Bombardier, CH, Ehde, DM, Stoelb, B, Molton, IR. The relationship of age-related factors to psychological functioning among people with disabilities. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21:281–297.

8. Booth, S, Kendall, M, Fronek, P, et al. Training the interdisciplinary team in sexualtiy rehabilitation following spinal cord injury: a needs assessment. Sex Disabil. 2003;21(4):249–261.

9. Boyle, PS. Training in sexuality and disability: preparing social workers to provide services to individuals with disabilities. J Soc Work Hum Sex. 1993;8(2):45.

10. Braithwaite, DO. From majority to minority: an analysis of cultural change from able-bodied to disabled. Int J Intercult Relat. 1990;14:465.

11. Chevalier, Z, Kennedy, P, Sherlock, O. Spinal cord injury, coping and psychological adjustment: a literature review. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:778–782.

12. Choquet, M, Du Pasquier Fediaevsky, L, Manfredi, R. National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), Unit 169, Villejuif, France: Sexual behavior among adolescents reporting chronic conditions: a French national survey. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20(1):62.

13. Cole, SS, Cole, TM. Sexuality, disability, and reproductive issues for persons with disabilities. In: Haseltine FP, Cole SS, Gray DB, eds. Reproductive issues for persons with physical disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H Brooks, 1993.

14. Cole, SS, Cole, TM. Sexuality, disability, and reproductive issues through the life span. Sex Disabil. 1993;11(3):189.

15. Cole, TM. Gathering a sex history from a physically disabled adult. Sex Disabil. 1991;9(1):29.

16. Cornelius, DA, Chipouras, S, Makas, E, et al. Who cares? A handbook on sex education and counseling services for disabled people. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1982.

17. Ducharme, S, Gill, KM. Sexual values, training, and professional roles. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1991;5(2):38.

18. Edwards, DF, Baum, CM. Caregivers’ burden across stages of dementia. Occup Ther Practice. 1990;2(1):13.

19. Ferreiro-Velasco, ME, Barca-Buyo, A, Salvador De La Barrera, S, et al. Sexual issues in a sample of women with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2004.

20. Fisher, TL, Laud, PW, Byfield, MG, et al. Sexual health after spinal cord injury: a longitudinal study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(8):1043.

21. Froehlich, J. Occupational therapy interventions with survivors of sexual abuse. Occup Ther in Health Care. 1992;8(2-3):1.

22. Gallup Report, August 2002.

23. Gender, AR. An overview of the nurse’s role in dealing with sexuality. Sex Disabil. 1992;10(2):71.

24. Giaquinto, S, Buzzelli, S, Di Francessco, L, et al. Evaluation of sexual changes after stroke. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(3):302.

25. Goldstein, H, Runyon, C. An occupational therapy education module to increase sensitivity about geriatric sexuality. Phys Occup Ther Geriatrics. 1993;11(2):57.

26. Greydanus, DE, Rimsza, ME, Newhouse, PA. Adolescent sexuality and disability. Adolescent Med. 2002;13(2):223.

27. Griffith, ER, Lemberg, S. Sexuality and the person with traumatic brain injury: a guide for families. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1993.

28. Halstead, LS, Halstead, MG, Salhoot, JT, et al. Sexual attitudes, behavior and satisfaction for able-bodied and disabled participants attending workshops in human sexuality. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1978;59(11):497–501.

29. Haseltine, FP, Cole, SS, Gray, DB. Reproductive issues for persons with physical disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H Brooks; 1993.

30. Hayden, N. How to satisfy a woman every time. New York: Bibli O’Phile; 1982.

31. Hebert, L. Sex and back pain. Bloomington, MN: Educational Opportunities; 1987.

32. Hite, S. The Hite Report: a nationwide study of female sexuality. New York: Seven Stories Press; 1991.

33. Hite, S. The Hite report on male sexuality. New York: Knopf; 1981.

34. Kaufman, M, Silverberg, C, Odette, F. The ultimate guide to sex and disability. San Francisco: Cleis Press; 2003.

35. Kettl, P, Zarefoss, S, Jacoby, K, et al. Female sexuality after spinal cord injury. Sex Disabil. 1991;9(4):287.

36. Korpelainen, JT, Nieminen, P, Myllyla, VV. Sexual functioning among stroke patients and their spouses. Stroke. 1999;30(4):715.

37. Krause, JS, Crewe, NM. Chronological age, time since injury, and time of measurement: effect on adjustment after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:91.

38. Kroll, K, Klein, EL. Enabling romance. New York: Harmony Books; 1992.

39. Lefebvre, KA. Sexual assessment planning. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1990;5(2):25.

40. Lemon, MA. Sexual counseling and spinal cord injury. Sex Disabil. 1993;11(1):73.

41. Low, WY, Zubir, TN. Sexual issues of the disabled: implications for public health education. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2000;12(suppl):S78.

42. Mackelprang, R, Valentine, D. Sexuality and disabilities: a guide for human service practitioners. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 1993.

43. Maller, JJ, Thomson, RHS, Lewis, PM, et al. Traumatic brain injury, major depression, and diffusion tensor imaging: making connections. Brain Res Rev. 2010;64:213–240.

44. McCabe, MP, Taleporos, G. Sexual esteem, sexual satisfaction, and sexual behavior among people with physical disability. Arch Sexual Behavior. 2003;32(4):359.

45. McComas, J, Hebert, C, Giacomin, C, et al. Experiences of students and practicing physical therapists with inappropriate patient sexual behavior. Phys Ther. 1993;73(11):762–769.

46. Neufeld, JA, Klingbeil, F, Bryen, DN, et al. Adolescent sexuality and disability. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2002;13(4):857.

47. Neistadt, ME, Freda, M. Choices: a guide to sexual counseling with physically disabled adults. Malabar, FL: Krieger; 1987.

48. Nosek, M, Rintala, D, Young, M, et al. Psychological and psychosocial disorders: sexuality issues for women with physical disabilities. Rehabil Res Development Progress Reports. 1997;34:244.

49. Pedersen, W, Kristiansen, HW. Homosexual experience, desire and identity among young adults. J Homosex. 2008;54:68–102.

50. Phillips, DM, Sudol, KM, Taylor, CL, et al. Lubricants containing N-9 may enhance rectal transmission of HIV and other STI’s. Contraception. 2004;70(2):1007.

51. Rabin, BJ. The sensuous wheeler. Long Beach, CA: Barry J Rabin; 1980.

52. Rintala, D, Howland, C, Nosek, M, et al. Dating issues for women with physical disabilities. Sex Disabil. 1997;15(4):219.

53. Romeo, AJ, Wanlass, R, Arenas, S. A profile of psychosexual functioning in males following spinal cord injury. Sex Disabil. 1993;11(4):269.

54. Sandowski, C. Responding to the sexual concerns of persons with disabilities. J Soc Work Hum Sex. 1993;8(2):29.

55. Scott, R. Sexual misconduct. PT Magazine Phys Ther. 1993;1(10):78.

56. Sipski, M, Alexander, C. Sexual function in people with disability and chronic illness. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1997.

57. Smith, M. Pediatric sexuality: promoting normal sexual development in children. Nurse Pract. 1993;18(8):37.

58. Sobsey, D, Randall, W, Parrila, RK. Gender differences in abused children with and without disabilities. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21(8):707.

59. Stockard, S. Caring for the sexually aggressive patient: you don’t have to blush and bear it. Nursing. 1991;21(11):72.

60. Sunnerville, P, McKenna, K. Sexuality education and counseling for individuals with a spinal cord injury: implications for occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 1998;61:275–279.

61. Suris, JC, Resnick, MD, Cassuto, N, et al. Sexual behavior of adolescents with chronic disease and disability. Adolesc Health. 1996;19(2):124.

62. Swartz, DB. A comparative study of sex knowledge among hearing and deaf college freshmen. Sex Disabil. 1993;11(2):129.

63. Verduyn, WH. Spinal cord injured women, pregnancy, and delivery. Sex Disabil. 1993;11(3):29.

64. Weppner, DM, Brownscheidle, CM. The evaluation of the health care needs of women with disabilities. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5(4):210.

65. Yim, SY, Lee, IY, Yoon, SH, et al. Quality of marital life in Korean spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord. 1998;36(12):826.

66. Young, ME, Nosek, MA, Howland, C, et al. Prevalence of abuse of women with physical disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(12 suppl 5):S34.

67. Zani, B. Male and female patterns in the discovery of sexuality during adolescence. J Adolesc. 1991;14:163.

Amador, MJ, Lynn, CM, Brackett, NL, A guide and resource directory to male fertility following spinal cord injury/dysfunction. Miami Project to Cure Paralysis, 2000.

Gregory, MF. Sexual adjustment: a guide for the spinal cord injured. Bloomington, IL: Accent On Living; 1993.

Greydanus, DE. Caring for your adolescent: the complete and authoritative guide. New York: Bantam Books; 2003.

Karp, G. Disability and the art of kissing. San Rafael, Calif.: Life on Wheels Press; 2006.

Kaufman, M, Silverberg, C, Odette, F. The ultimate guide to sex and disability. San Francisco: Cleis Press; 2003.

Kempton, W, Caparulo, F. Sex education for persons with disabilities that hinder learning: a teacher’s guide. Santa Barbara, CA: James Stanfield; 1989.

Leyson, JF. Sexual rehabilitation of the spinal-cord-injured patient. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1991.

Mackelprang, R, Valentine, D. Sexuality and disabilities: a guide for human service practitioners. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 1993.

Sandowski, C, Sexual concern when illness or disability strikes. Springfield, IL, 1989, Charles C Thomas. Resources for people with disabilities and chronic conditions, ed 2, Lexington, KY, Resources for Rehabilitation, 1993.

Shortridge, J, Steele-Clapp, L, Lamin, J. Sexuality and disability: a SIECUS annotated bibliography of available print materials. Sex Disabil. 1993;11(2):159.

Sipski, M, Alexander, C. Sexual function in people with disability and chronic illness. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1997.

Sobsey D, Gray S, eds. Disability, sexuality, and abuse. Baltimore: Paul H Brooks, 1991.

Video available for purchase from the Kessler Medical Rehabilitation Research & Education Center

2198 Sixth Street, Suite 100, Berkeley, CA 94710-2204

American Association of Sex Education Counselors and Therapists

435 N. Michigan Avenue, Suite 1717, Chicago, IL 60611

Association for Sexual Adjustment in Disability

Coalition on Sexuality and Disability

122 East Twenty-third Street, New York, NY 10010

Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS)

130 West Forty-second Street, Suite 2500, New York, NY 10036

Sexuality and Disability Training Center

University of Michigan Medical Center

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

1500 E. Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

The Task Force on Sexuality and Disability of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine

Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline