Leisure Occupations

Leisure and life satisfaction for persons with physical disabilities

Benefits of play and laughter in leisure occupations

Meaningful leisure occupations: age, cultural issues, and gender

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Discuss the benefits of leisure for adults.

2 Describe the key areas in which humor can be used.

3 Understand the differing needs that people in different stages of life have.

4 Identify specific strategies to promote leisure activity for persons with disabilities.

Participating in meaningful leisure occupations is vital to a healthy, balanced lifestyle.6,41,50 As an area of occupation, leisure is defined in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework as “a nonobligatory activity that is intrinsically motivated and engaged in during discretionary time, that is, time not committed to obligatory occupations such as work, self-care, or sleep”46 (p. 632). Key phrases in the definition are that these activities are intrinsically motivated and that they are not obligatory. In other words, people participate in leisure occupations that they choose and enjoy. For instance, for some people cooking could be a chore, whereas for others it is a joyful pleasure.

Leisure time may be spent in a variety of ways indicative of an individual’s unique interests. Examples of leisure occupations are reading, playing games, participating in sports, doing arts and crafts, engaging in outdoor activities (biking, hiking, fishing), cooking, taking a yoga class, exercising at the gym, going to concerts, watching movies, and so on. Because of the uniqueness of individuals, this list is as long as there are people who participate in leisure occupations.

Leisure and Life Satisfaction for Persons with Physical Disabilities

When adults sustain injuries (e.g., traumatic brain injury, stroke, spinal cord injury, carpal tunnel syndrome), have health conditions (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, arthritis), or experience life transitions (e.g., empty nest syndrome, menopause, retirement) that disrupt normal habits and routines, they face devastating losses. Loss of work, social activities, and meaningful leisure activities may contribute to depression, and the self must be redefined.64

Occupational therapists are skilled in collaborating with people with physical disabilities to assist them in resuming a full life.62 It has been suggested that one method of measuring whether a person is fully engaged in life is to consider the individual’s participation in leisure activities.11,51 This is especially important because research indicates that the perception of leisure satisfaction by adults with physical disabilities is the most significant predictor of life satisfaction.31,33 Depressive symptoms have also been shown to decrease when the number and variety of pleasant activities increase.18,25,56 Engaging in leisure activities provides a receptive environment for opportunities for socialization and friendship making in which people with physical disabilities have a chance to demonstrate their occupational skills to others who might not otherwise view those with a disability as being capable or as a friendship candidate.53

Additionally, leisure has been shown to contribute to individual development and well-being and provides a significant mechanism of coping.46,65,66

Sadly, however, studies indicate that most leisure activities are abandoned after the onset of a physical disorder such as rheumatoid arthritis or stroke.51,69 Adults with physical disabilities seem to relinquish activities that are purely for enjoyment, especially community-based social activities, and focus their effort and time on activities of daily living and work.51 The emphasis on the physical model of recovery is most likely due to (1) health professionals who deliver treatment with a focus on mobility and independence in activities of daily living and (2) the fact that rehabilitation outcome measures are commonly based on these factors.51 Occupational therapists need to recognize that people often experience difficulty adapting their interests and activities by themselves after a physical or neurologic disorder.

A randomized, controlled study of stroke survivors supports the need for occupational therapists to address the leisure area of occupation for clients to engage in leisure interests and activities after therapy is discontinued.18 Sixty-five clients were randomly assigned to three groups: leisure rehabilitation, conventional occupational therapy treatment, and control. The baseline number and frequency of leisure activities in the three groups demonstrated no significant difference between the groups on admission to the hospital.

After discharge from the hospital, the leisure rehabilitation group and the conventional occupational therapy group were treated by the same occupational therapist for 30 minutes one time per week for 3 months and then one 30-minute session every 2 weeks for 3 months. Each person in the leisure rehabilitation group was given an individualized program that included “advice and help … in the following broad categories: treatment (e.g., practice of transfers needed for leisure pursuits); positioning; provision of equipment; adaptations; advice on obtaining financial assistance and transportation; liaison with specialist organization, and providing physical assistance (e.g., referral to voluntary agencies).”18

The occupational therapy group received individualized treatment by the same therapist for the same amount of time. Interventions included “transfers, washing and dressing practice, and, where appropriate, perceptual treatments. … No reference was made to the importance of continuing previous interests, and no help or advice was offered to encourage participation in leisure pursuits”18 (p. 285). At 3 and 6 months after discharge, an independent assessor readministered the leisure questionnaire, which showed that the leisure rehabilitation group had significantly higher leisure scores than did the conventional occupational therapy group and the control group.18

Thus, adults with physical disabilities may give up leisure activities because they are not aware of ways to adapt valued activities so that they may participate in them again, or they may not know about new hobbies or crafts that they might enjoy. Occupational therapists have an important role in helping people both explore and plan engagement in leisure occupations so that they may participate in activities that bring joy to life.12,62,64 Engagement in serious leisure (term used in the literature to indicate fulfilling leisure activities that engage the individual’s special skills, knowledge and experience) has been positively associated with positive affect.31

Benefits of Play and Laughter in Leisure Occupations

When talking about participating in leisure occupations, people often use the word play. Some examples are to play golf, play the piano, play sports, play cards, play board games, and so on. Play allows adults to escape the reality of everyday life and immerse themselves in a world of carefree spontaneity that provides meaning to their existence. Play suggests fun, and fun is often accompanied by laughter.

Many physical health benefits of laughter have been demonstrated through numerous research studies. For example, immune cells increase and stress hormones decrease, thereby possibly preventing illness or helping in recovery.10,54,63 Some people experience relief from pain and a sense of well-being after hearty laughter.1,17 Laughter also benefits people psychologically and psychosocially.19,57,60,68 Laughing together facilitates bonding, reduces anxiety, and improves coping27,38—all important factors in a therapeutic alliance between the occupational therapist and client (Box 16-1).

Facilitating psychosocial and physical adaptations is integral to occupational therapy, and given the current health care climate of high productivity and short hospital and rehabilitation stay, it is imperative that occupational therapists be able to quickly form a therapeutic alliance with their clients. Humor and laughter are natural ways that therapists and clients connect. Recent studies have found that all of the occupational therapists who were interviewed or surveyed agreed that humor has a place in occupational therapy.35,40,60,67

In a national cross-sectional randomized survey of 283 occupational therapists that examined their attitudes and use of humor in interacting with adult clients with physical disabilities, humor was classified into four key areas: (1) building relationships, (2) helping clients cope with adversity, (3) promoting clients’ physical health, and (4) facilitating compliance with treatment.60 Although therapists reported positive attitudes about humor in all four of these areas, most were actually using humor only to build relationships and to help clients cope. The majority of therapists felt comfortable using spontaneous humor with clients as part of the therapeutic use of self rather than using planned humor as a therapeutic intervention.

People who are disabled may need to learn ways to adapt to their new circumstances. Humor is a skill that can be learned and may provide the client with the ability to manage concerns related to his or her health and life situations. Within a larger relational context, humor may be modeled by occupational therapists to teach coping skills. Bandura described four essential factors for modeling to be an effective intervention.7 First, the client must have adequate attention span to focus on the modeled behavior. Second, he or she must be able to cognitively form and retain a mental image of the behavior. Third, the client must be able to recall the image and then produce the behavior. Last and perhaps most important, the client must have the motivation to engage in the behavior.

The intimacy that humor presumes may provide the client with a sense of connection with the therapist. This connection, which occurs on conscious and unconscious levels, has many positive benefits for clients. When the therapist is able to demonstrate professionalism and empathy with a touch of humor, a client may feel less alone and more cared for as an individual.26,60 An improved sense of equality with the health care provider may occur that could increase the client’s active involvement in her or his treatment.2,19

Although laughter has been shown to be beneficial, there are times when humor may not be a good choice and must be used with caution or avoided altogether. Seizures and cataleptic or narcoleptic attacks may follow a laughter episode in a small number of people.24 In addition, because laughing increases abdominal and thoracic pressure, people with recent abdominal surgery, upper body fractures, acute asthma, or “preexisting arterial hypertension and cerebral vascular fragility”24 (p. 1857) should not be encouraged to laugh.

Leisure exploration is defined in the “Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (2nd edition)”46 as “identifying interests, skills, opportunities, and appropriate leisure activities,” and leisure participation is “planning and participating in appropriate leisure activities; maintaining a balance of leisure activities with other areas of occupation; and obtaining, using, and maintaining equipment and supplies as appropriate” (p. 632). While exploring leisure with the client, the occupational therapist will be concerned with the appropriateness of such occupations with respect to age, gender, cultural fit, and meaning for the specific individual—concerns addressed in the next section.

Meaningful Leisure Occupations: Age, Cultural Issues, and Gender

Clients choose the leisure occupations that they want to pursue.46,62 Choices may be based on past experiences or on a desire to explore something new. As people move through the developmental stages of adulthood, the occupation of leisure may vary in intensity and time allotted. The continuity theory of aging suggests that personality plays a major role in adjustment to aging. Because personality does not radically change throughout life, one’s preferences, lifestyle, and activities remain relatively the same in individuals exhibiting successful aging.5,13,44,65

Age and Leisure

Knowledge of the typical progression through adulthood, common life stage choices of leisure activities, and the ways that physical disabilities may disrupt participation in leisure activities is critical for occupational therapists. Armed with this information, therapists are able to discover gaps in developmental stages and to assist clients in the mastery of valued and meaningful occupations.20

Young Adulthood (20 to 40 Years)

Young adults are typically healthy, active, working, and engaged in relationships. Erikson’s sixth stage of psychosocial development, intimacy versus isolation, describes young adulthood as a time in life when people know who they are and are ready to form intimate relationships with others.49 Inability to make commitments on an intimate level may lead to isolation. Levinson views this age period as a time of becoming independent from parents, choosing and beginning an occupation, and imagining one’s dream future.49 Young adults typically settle down and choose interests that encompass family, work, and leisure activities.

Examples of leisure activities in which young adults engage may include social and family group activities, sports (e.g., basketball, off-road biking), exercise, travel, computer games, surfing and social networking on the Internet, hobbies and crafts (e.g., scrapbooking), outdoor activities, dancing, dating, and sex.

Accidents or physical disorders affecting an individual’s areas of occupation, performance skills, and body functions can severely impede progress through the normal activities of young adulthood and may delay the development of age-related roles such as spouse, parent, employer/employee, social participant, participator in leisure occupations, and sexual being. Persons who are at the beginning stage of adulthood and who sustain an irreversible injury may need to redefine themselves to successfully navigate the aging process. Leisure problems may include social isolation and changes in relationships, lack of ability to perform favorite sports, difficulty traveling, and decreased knowledge of how to creatively express the self.28,33,64 A sense of incompetence may ensue that could lead to depression.

Middle Adulthood (40 to 65 Years)

People in this age group are typically immersed in work and family life. They have usually developed expertise in their chosen field of employment and may have risen to supervisory levels. Financial independence is attained as people purchase homes and cars and build a nest egg. Some adults in this age group experience a midlife review of self and career and may change careers or retire. This is the stage of generativity versus stagnation (Erikson’s seventh stage of psychosocial development) in which the person enjoys developing the skills and talents of younger people (e.g., serving as a sports coach or work mentor).49 Lack of generativity may lead to stagnation in life, disappointment, and burnout.20

Examples of leisure activities typical of this age group are friend and family activities, sports (e.g., golf, bowling, coaching), card games, Internet surfing, socializing and shopping, travel, pet care, gardening, movies, attending plays and concerts, boating, fishing, reading, television, bike riding, dating, and sexual activity with a spouse or partner.

Disruption caused by a physical disability can impair the individual’s ability to engage in cherished leisure occupations. Spouses or significant others are called on to be caregivers, and the relationship may undergo changes. Leisure occupations such as travel and fishing may be put aside for the more immediate concerns of learning to cope with self-care, rehabilitation exercises, and therapeutic equipment.61,69 Friend relationships often change as well. For example, if two men had a friendship based on golfing every Saturday and one of them suffers a stroke and needs to use a wheelchair, either they will have to be proactive and figure out a way to enjoy each other’s company in a new way (such as playing golf with adapted equipment or trying out a new activity that they both enjoy), or they may drift apart. Finally, changes caused by life transitions such as menopause and empty nest syndrome are ameliorated many times by engagement in leisure occupations. For example, a qualitative study of women experiencing menopause indicated that leisure activities not only provide women with a sense of familiarity, security, and continuity but also provide them with opportunities to develop new interests and to focus on themselves.52

Late Adulthood (65 Years and Older)

Occupational roles typically go through transformations during this age span. Some changes seen in older adults include a shift of emphasis from parent to grandparent and worker to retiree or volunteer. As time spent in work/career diminishes, free time increases, and leisure occupations come into full bloom. The interests and activities that were put aside during career attainment can now be given full rein.20 Erikson’s last stage of psychosocial development (stage 8, ego integrity versus despair) is described as the time when people review their lives and hopefully accept the life cycle as being complete and satisfying.49 The “use it or lose it” principle is particularly important as people age. If activity levels are not maintained, strength, coordination, and skills may deteriorate rapidly.49 Some aspects of aging that are considered fairly normal include diminishing hearing and eyesight, arthritis, and decreased sensory abilities, as well as general aches and pains.

Examples of leisure activities in which older adults engage are dining with or cooking for friends and family, social activities, card games, bingo, travel, sports (e.g., golf, game attendance or viewing on TV), walking, exercise at the gym, swimming, boating, sexual activity with a spouse or partner, reading, television, pet care, gardening, and hobbies (e.g., crafts, collecting, scrapbooking).

If a physically disabling event or disease progression occurs, spouses or significant others may be called on to assist their partners in performing daily living activities, including leisure. This can be problematic because the caregiver may also be advanced in age and may not be well suited to provide the care needed.42 Consequently, leisure activities may be forgotten except for sedentary activities such as television viewing.69

For some, isolation and depression could set in and diminish the person’s quality of life. A quantitative study of 383 retirees indicated that leisure plays a significant role in achieving a high level of life satisfaction, which the authors purport is equivalent to successful adaptation to retirement.44 In another study of 324 older Swedes living in the community, researchers discovered that people who increased participation in leisure activities reported being more satisfied with life. “The results suggest that maximizing activity participation is an adaptive strategy taken by older adults to compensate for social and physical deficits in later life”58 (p. 528). Mental acuity may also be strengthened or preserved by engaging in novel activities. Engagement with life is vital to successful aging.59

Culture and Leisure

Because of the increasing diversity of the U.S. populace, occupational therapists must have knowledge of how culture affects the choices and performance of leisure activities for clients. The U.S. Census Bureau (www.census.gov) reports that although the white population is still the majority (65%), by the year 2050, whites and minority groups overall will be roughly equal in size. Ethnic groups are currently concentrated in various areas of the country (Table 16-1). Thus, depending on where occupational therapy is delivered, therapists should make themselves familiar with leisure activities related to the culture of their clients (Table 16-2).

TABLE 16-1

Ethnic Groups in the United States, 2009 Population Estimates

| Ethnic Group | Percentage of Population | Population Centers |

| White | 65.1% | Midwest and Northeast |

| Hispanic or Latino | 15.8% | Southwest and California |

| Black or African American | 12.3% | Southeast and Mid-Atlantic |

| Asian American | 4.4% | West and Northeast |

| American Indian and Alaskan Native | 0.9% | Northwest, West, Southwest, and Midwest |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders | 0.1% | Hawaii and West |

| Two or more races reported | 1.4% |

Data from U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2009 population estimates. Available at: www.census.gov.

TABLE 16-2

Examples of Leisure Interests and Occupations by Ethnicity

| Ethnic Group | Possible Leisure Interests and Occupations |

| Hispanic/Latino | Music, dancing, video games, sports (e.g., soccer, races, arena football), needlework, concerts, movies, TV, socializing, cooking, travel to Mexico and Central/South America (minimal domestic US travel) |

| Black/African American | Socializing, sports (e.g., bowling, baseball, basketball), cooking, games (e.g., cards, gambling, board), TV, computers/Internet, running, weightlifting, woodworking, remodeling, sewing, quilting, gardening, music, dancing |

| Asian American | Board games (e.g., GO), tile games (e.g., mahjong), traditional cooking and arts, Asian language classes, gardening, sewing, tai chi, yoga, walking, computers, Internet surfing/shopping, travel to Asian destinations4 |

| American Indian | Sports (e.g., running, lacrosse, longball), outdoor traditions (e.g., canoe, kayak, archery), recreational pastimes (e.g., cup and ball, dice or deer button game, snowsnake), powwow (dancing, arts) |

Sources: www.artsedge.kennedy-center.org; www.diversitylab.uiuc.edu/shinew; www.cpanda.org; www.goldsea.com/Features2/Essays/get; Allison & Geiger (1993).

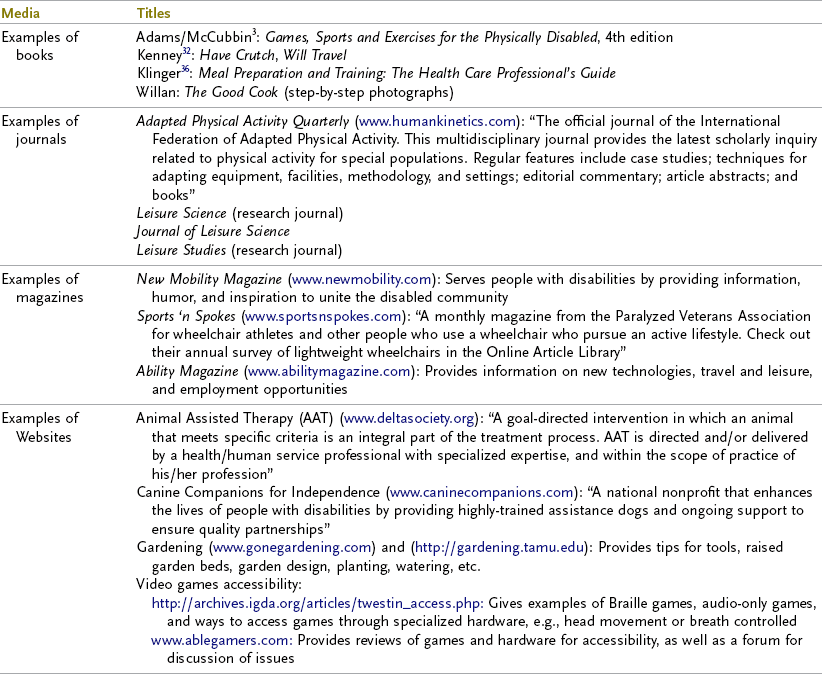

Leisure Occupations Related to Culture

Games and leisure occupations instruct, inspire, and reflect the values and beliefs of the parent cultures. For persons immigrating to a new country (e.g., Hispanics to the United States), leisure activities can be used to maintain connections with their heritage. Other possible uses of leisure that aid community integration are to (1) gain pleasure from the new environment and people and (2) learn language and customs.34 Watching television and reading are two ways that newcomers use leisure to improve conversational skills and to understand cultural features.4 Depending on the interest of the client involved, occupational therapists may offer leisure occupations that (1) reflect the client’s traditional background, thus fostering security in a new country, or (2) provide leisure experiences of the new country to increase learning, comfort, and integration (Table 16-2). Keeping the leisure interventions client centered is the critical element to a successful outcome. Table 16-3 presents ideas for leisure resources.

Leisure-Time Physical Activity by Gender, Age, and Racial/Ethnic Groups

Physical inactivity has been associated with various health risk factors such as obesity; cardiovascular disease, including stroke; diabetes; some cancers; and premature mortality.43 Occupational therapists can aid clients to live a healthy lifestyle by encouraging them to participate in some type of leisure-time occupation that involves physical exercise at least several times a week. Some examples of leisure occupations that provide physical exercise but could be more attractive alternatives to some people are dancing, swimming, boating, bowling, golfing, gardening, and yoga.

To discover trends in physical activity levels, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted a randomized telephone survey of 170,423 persons from 35 states and the District of Columbia and asked, “During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercise such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?” Analysis of the data revealed that women, older adults, and the majority of racial/ethnic groups participated the least in leisure-time physical activities.29 Blacks, Hispanics, and American Indians or Alaskan Natives more often reported fair or poor health, obesity, diabetes, and lack of leisure-time physical activity than did whites, Asians, or Pacific Islanders. Women in all cultures surveyed engaged in the least amount of physical activity.21,48

Some barriers to leisure-time physical activity have been identified. Although many people of different cultures and ages believe that movement (e.g., exercise, gardening, walking) yields positive benefits such as improved health and appearance, they do not engage in physical activities because of “self-consciousness and lack of discipline, interest, company, enjoyment and knowledge.”16 Other barriers to activity were identified, such as lack of transportation, prohibitive cost, and perceived lack of safety. Social issues such as gender roles for activity and poor support from the family were also identified by minority women. As a barrier to activity, these women additionally reported problems with (1) language, (2) isolation in the community, and (3) childcare because of lack of relatives in the area. While planning intervention, occupational therapists can collaborate with clients to address these problems, find community resources, and develop strategies to improve participation in leisure-time physical activities.

Leisure Occupations: Evaluation and Intervention

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework focuses on a client-centered approach and mandates that the first step in the process be that occupational therapists develop an occupational profile collaboratively with clients and family/caregivers.46 The profile includes the client’s occupational history, past and current interests, performance, and values. Knowledge of the problems and goals that the client and family/caregivers consider important gives the therapist a basis for a meaningful intervention plan. Evaluation includes formal and informal assessments conducted initially and over the course of the therapy process to guide the therapist in providing an individualized intervention program that meets the client’s expressed needs and desires. Examples of possible assessments that address the leisure area of occupation and a description of each are presented in Table 16-4.

TABLE 16-4

Leisure Assessments and Descriptions Used by Occupational Therapists

| Assessments | Descriptions |

| Occupational Profile46 | Interview with the client (and family/caregivers if appropriate) to gather information about demographics, language, health status, and social and medical history. Questions addressing why the client needs occupational therapy services, what his or her concerns are, the client’s occupational history (e.g., values, meanings associated with life experiences), and what the client’s priorities are |

| Canadian Occupational Performance Measure39 | Interview conducted before and after interventions to describe problems, level of satisfaction in performing activities, and level of perceived performance abilities in areas of self-care, productivity, and leisure |

| Role Checklist45 | Interview to discover past, present, and future occupational roles (including leisure roles) and their value to the client |

| Activity Card Sort8 | Picture cards of adults performing instrumental, social-cultural, and leisure activities. Client sorts them into piles depending on their interest level. Provides a “retained activity level” score indicating engagement levels of performance of past and current activities |

| Modified Interest Checklist (available from Model of Human Occupation Clearinghouse) | Checklist of 68 activity items that assesses the client’s level of interest (casual, strong, or no interest). Includes many leisure-time activities |

| Leisure Attitude Measurement Scale55 | Scale of 36 items addressing attitudes toward leisure in three areas: cognitive, affective, and behavioral. Rated on a 5-point scale from “never true” to “always true” |

| Leisure Motivation Scale9 | Scale of 48 items addressing motivation to participate in leisure in four areas: intellectual activities, social activities, mastery activities, and stimulus-avoidance activities. Rated on a 5-point scale from “never true” to “always true” |

| Quality of Life Scale14,23,69 | Perceived quality of life on a scale of 16 items (e.g., material comforts, expressing yourself creatively, socializing, participating in active recreation). Rated on a Likert scale of “very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied” |

| Play and Laughter Assessment37 | Informal interview to determine the client’s attitude toward use of humor, sense of humor, types of humor that the client has enjoyed, etc. |

| Performance Skills | Assessment of the client’s ability to perform leisure occupations, including motor skills, process skills, communication, and interaction skills. These may be assessed by formal tests and by observation and analysis of client’s performance during activity engagement in the appropriate context (e.g., analyze the client’s ability to hold and manipulate cards during a card game; analyze the client’s ability to put bait on a fish hook, manage the rod and reel, and catch and remove fish from the hook while seated by a lake) |

| Ohio Functional Assessment Battery: Standardized Tests for Leisure and Living Skills47 | Designed for use in cognitively impaired individuals. Structured interview/questionnaire assessing interests, resources, participation, motivation, and barriers to therapy. Has 3 test options: Functional Living Skills Assessment, Quick Functional Screening Test, and Recreation and Leisure Profile |

| Context | Assessment of cultural, physical, social, personal, spiritual, temporal, and virtual contexts that may influence participation in leisure occupations |

| Client Factors | Assessment of body systems that support participation in leisure occupations (e.g., mental, sensory, neuromusculoskeletal, cardiovascular, respiratory and speech functions, pain, skin) |

Intervention: Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way

Using information gathered during the evaluation process, an intervention plan incorporating leisure occupations is developed that the client and family/caregivers view as important to improving quality of life. Clients (including family or caregivers as necessary) and therapists develop goals and plan interventions together, thus ensuring that the client is motivated to engage in therapy sessions to the best of his or her ability.46 In occupational therapy, leisure occupations can be a means and an end. As a means of intervention, the client is provided with the therapeutic use of leisure that is motivating because it is chosen and fun. Leisure as an end is seen when the client voluntarily engages in leisure occupations after therapy intervention ceases.46 When developing discharge plans that include leisure, the therapist should consider “attributes of novelty and challenge, meaningful use of time, and identity construction,” which are imperative to the continued growth, adaptation, and quality of life of clients.64 Occupational therapists may offer a variety of leisure activities delivered to individuals or groups, depending on the relevance to the client’s interests, abilities, and activity demands. In the case of Kris (see Case Study: Kris), individual activities need to be mastered before group activity can be considered.

Balloon volleyball is a fun and social activity. For example, in a long-term care facility, residents with appropriate cognitive and motor skills can be organized into two teams, seated and facing each other. A real or simulated volleyball net is erected between the two teams and a balloon is hit back and forth. Music adds to the enjoyable atmosphere. This game can meet several occupational therapy goals such as improving eye pursuit, upper extremity range of motion, socialization, and cognition (keeping track of the score). In addition, because joking and laughing often occur, physical, social, and psychological benefits may be gained (see Box 16-1). The therapist must ensure that clients are interested in participating and that each person is safe, with wheelchairs locked and, if necessary, seat belts attached. Cardiac patients may not be appropriate to include because of the upper extremity workout and increased respiration, heart rate, and blood pressure that could occur.

Adapting the Activity for Success

Occupational therapists are uniquely qualified to adapt the activity, including the equipment, the environment, or the nature of the activity, to make leisure occupations accessible to clients. By participating in leisure occupations that are meaningful, clients are able to continue to make positive adaptations that lead to greater life satisfaction. Table 16-5 describes some leisure occupations and possible adaptations.

TABLE 16-5

Examples of Adapted Leisure Occupations

| Leisure Occupation | Possible Adaptations |

| Gardening | Raised flower or vegetable garden beds to be accessible from a chair or wheelchair. Nonskid surface under pots to prevent sliding during potting |

| Golf | Adapted golf clubs (e.g., constructed to be used from a seated or wheelchair position or to be used one-handed), lower-extremity prosthetics specially made for golf |

| Playing cards | Card shuffler, card holder (Figure 16-1), large-print or Braille cards |

| Computer activities or Internet surfing | Large monitor screen, large print font, voice-activated controls or software (e.g., Dragonspeak) |

| Cooking | Energy conservation techniques, sliding instead of lifting heavy pots, nonskid surface to prevent slippage, rocker knife, perching stool |

| Pets | Canine companions to manage daily tasks (e.g., open drawers and doors, acknowledge phone ringing, obtain objects), as well as provide love and licks. Therapy dogs to visit clients in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and homes to bring joy and opportunities for touch (Figure 16-2). Pets such as fish, cats, dogs, and others provide companionship and may promote motivation for engagement in caring activities |

| Bike riding | For persons with lower-extremity weakness or paralysis, handcycles may be purchased. These bikes are propelled and controlled by arm strength and coordination (Figure 16-3) |

Level of Functioning

Occupational therapists view the client as a whole person with a myriad of dimensions (e.g., physical, cognitive, spiritual, psychological). Leisure occupations are self-enhancers that add joy and pleasure to life. For effective implementation, activities need to be analyzed according to the individual’s level of functioning (e.g., performance skills, performance patterns, client factors, activity demands, and context). Examples of clients by level of function, along with leisure occupations that are meaningful to the individual, are described in the case studies examining Tina, John, and Miguel.

Summary

Occupational therapists assist clients in attaining life satisfaction through a variety of occupations that are meaningful to the individual. Engaging and re-engaging in leisure occupations, which may include social interactions, movement, playfulness, and pleasure, are important aspects of a balanced lifestyle. Realizing that lack of leisure activities may lead to isolation and depression and detrimentally affect an individual’s recovery and joy of life, occupational therapists need to include leisure evaluation, intervention planning, and implementation for persons with physical disabilities. Consideration of the client’s age, gender, culture, interests, and environment is paramount when investigating or implementing leisure so that intervention is client centered. A skilled occupational therapist can facilitate participation in meaningful leisure occupations that may lead to improved psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and quality of life.

1. What can the absence of a meaningful leisure occupation lead to for people with a physical disability?

2. List five psychosocial benefits and five physical benefits of leisure activities.

3. Why is the client’s cultural background important?

4. When should humor and laughter be used with caution?

5. What four factors are essential for modeling to be an effective intervention?

6. Why is it important for the client to be involved in setting his or her own goals?

References

1. Abel, MH. Humor, stress, and coping strategies. Humor. 2002;15(4):365.

2. Adams, P, Gesundheit!. (with Mylander M), Rochester, Vt, Healing Arts Press, 1998.

3. Adams, RC, McCubbin, JA. Games, sports and exercises for the physically disabled, ed 4. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea & Febiger; 1990.

4. Allison, MT, Geiger, CW. Nature of leisure activities among Chinese-American elderly. Leisure Sci. 1993;15(4):309.

5. Atchley, RC. Social forces and aging: an introduction to social gerontology, ed 10. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth; 2004.

6. Backman, CI. Occupational balance: exploring the relationship among daily occupations and their influence on well-being. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71(4):202.

7. Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

8. Baum, CM, Edwards, D. Activity card sort. St. Louis, Mo: Washington University at St. Louis; 2001.

9. Beard, JB, Ragheb, MG. Measuring leisure motivation. J Leisure Res. 1983;15:219.

10. Bennett, MP, Zeller, JM, Rosenberg, L, McCann, J. The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(2):38. [45].

11. Bhogal, SK, Teasell, RW, Foley, NC, Speechley, MR. Community reintegration after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2003;10(2):107.

12. Blacker, D, Broadhurst, L, Teixeira, L. The role of occupational therapy in leisure adaptation with complex neurological disability: a discussion using two case study examples. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008;23(3):313.

13. Brown, CA, McGuire, FA, Voelkl, J. The link between successful aging and serious leisure. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2008;66(1):73.

14. Burckhardt, C, Archenholtz, B, Bjelle, A. Measuring the quality of life of women with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. A Swedish version of the Quality of Life Scale (QoLS). Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;21(4):190.

15. Butler, B. Overview of sports wheelchairs. Br J Occup Ther. 1997;4(2):66.

16. Dergance, JM, Calmbach, WL, Dhanda, R, et al. Barriers to and benefits of leisure-time physical activity in the elderly: differences across cultures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(6):863.

17. Dilley DS: Effects of humor on chronic pain and its relationship to stress and mood in a chronic pain population, doctoral dissertation, 2006, Alliant International University, Available through Dissertation Abstracts International.

18. Drummond, AER, Walker, MF. A randomized controlled trial of leisure rehabilitation after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 1995;9:283.

19. Du Pre, A. Humor and the healing arts: a multimethod analysis of humor use in health care. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998.

20. Edwards, D, Christiansen, CH. Occupational development. In: Christiansen CH, Baum CM, eds. Occupational therapy: performance, participation, and well-being. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 2005.

21. Eyler, AE, Matson-Koffman, D, Evenson, KR, et al. Correlates of physical activity among women from diverse/racial groups. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(3):239.

22. Fenech, A. The benefits and barriers to leisure occupations. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008;23(3):295.

23. Flanagan, J. A research approach to improving our quality of life. Am Psychologist/J Am Psychol Assoc. 1978;33(2):138.

24. Fry, W. The physiologic effects of humor, mirth, and laughter. JAMA. 1992;267(13):1857.

25. Fullagar, S. Leisure practices as counter-depressants: emotion-work and emotion-play within women’s recovery from depression. Leisure Sci. 2008;30:35.

26. Gilfoyle, EM. Caring: a philosophy for practice. Am J Occup Ther. 1980;34(8):517.

27. Godfrey, JR. Toward optimal health: the experts discuss therapeutic humor. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2004;13(5):474.

28. Guo, L, Lee, Y. Examining the role of leisure in the process of coping with stress in adult women with rheumatoid arthritis. Annu Ther Recreation. 2010;18:100.

29. Ham, SA, et al. Centers for Disease Control Weekly: prevalence of no leisure-time physical activity—35 states and the District of Columbia, 1988-2002. http://wwwcdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5304g4.htm. [2/6/04. Available online at].

30. Hampes, WP. The relationship between humor and trust. Humor. 1999;12(3):253.

31. Heo, J, Lee, Y, McCormick, B, Pedersen, PM. Daily experience of serious leisure, flow and subjective well-being of older adults. Leisure Studies. 2010;29(2):207.

32. Kenney, C. Have crutch, will travel. Denver, Colo: Tell Tale Publications; 2002.

33. Kensinger, K, Gibson, H, Ashton-Shaefer, C. Leisure in the lives of young adults with developmental disabilities: a reflection of normalcy. Annu Ther Recreation. 2007;15:45.

34. Kim, E, Kleiber, DA, Kropf, N. Leisure activity, ethnic preservation, and cultural integration of older Korean Americans. J Gerontol Social Work. 2001;36(1/2):107.

35. Klein, A. The healing power of humor. Los Angeles, Calif: Jeremy P. Tarcher; 1989.

36. Klinger, JL. Meal preparation and training: the health care professional’s guide. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1997.

37. Kolkmeier, LG. Play and laughter: moving toward harmony. In: Dossey BM, Keegan L, Kolkmeier LG, et al, eds. Holistic health promotion: a guide for practice. Rockville, Md: Aspen Press, 1989.

38. Kuiper, NA, Martin, RA. Laughter and stress in daily life: relation to positive and negative affect. Motivation Emotion. 1998;22(2):133.

39. Law, M, et al. Canadian occupational performance measure, ed 3. Toronto: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapy; 1999.

40. Leber, DA, Vanoli, EG. Brief report: therapeutic use of humor: occupational therapy clinicians’ perceptions and practices. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;50:221.

41. Matuska, KM, Christiansen, CH. A proposed model of lifestyle balance. J Occup Sci. 2008;15(1):9.

42. Martin, P. Family leisure experiences and leisure adjustments made with a person with Alzheimer’s. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2006;22(4):309.

43. MMWR Survell Summ 24 49(SS-2):1, 2000.

44. Nimrod, G. Retiree’s leisure: activities, benefits, and their contribution to life satisfaction. Leisure Studies. 2007;26(1):65.

45. Oakley, F, Kielhofner, G, Barris, R, Reichler, RK. The Role Checklist: development and empirical assessment of reliability. Occup Ther J Res. 1986;6(3):157.

46. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process (2nd edition). Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62(6):625.

47. Olsson, RH. Ohio Functional Assessment Battery: standardized tests for leisure and living skills. San Antonio, Tex: Therapy Skill Builders; 1994.

48. Outley, CW, McKenzie, S. Older African American women: an examination of the intersections of an adult play group and life satisfaction. Activities Adaptation Aging. 2006;31(2):19.

49. Papalia, DE, et al. Human development, ed 9. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

50. Parham, LD, Fazio, LS. Play in occupational therapy for children. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997.

51. Parker, CJ, Gladman, JR, Drummond, AE. The role of leisure in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 1997;19(1):1.

52. Parry, D, Shaw, SM. The role of leisure in women’s experiences of menopause and mid-life. Leisure Sci. 1999;21:205.

53. Pendleton, HM, Establishment and sustainment of friendship of women with physical disability: the role of participation in occupation. doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 1998. [Available through Dissertation Publishing, University of Michigan].

54. Pert, C. Molecules of emotion: why you feel the way you feel. New York: Scribner; 1997.

55. Ragheb, MG, Beard, JG. Measuring leisure attitude. J Leisure Res. 1982;14:155.

56. Riley, J. Weaving an enhanced sense of self and collective sense of self through creative textile making. J Occup Sci. 2008;15(2):63.

57. Robinson, VM. Humor and the health professions: the therapeutic use of humor in health care, ed 2. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1991.

58. Silverstein, M, Parker, MG. Leisure activities and quality of life among the oldest old in Sweden. Res Aging. 2002;24(5):528.

59. Son, JS, Kerstetter, DL, Yamal, C, Baker, BL. Promoting older women’s health and well-being through social leisure environments: what we have learned from the Red Hat society. J Women Aging. 2007;19(3/4):89.

60. Southam, M. Therapeutic humor: attitudes and actions by occupational therapists in adult physical disabilities settings, Occup Ther. Health Care. 2003;17(1):23.

61. Shannon, CS. Breast cancer treatment: the effect on and therapeutic role of leisure. Am J Recreation Ther. 2005;4(3):25.

62. Suto, M. Leisure in occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1998;65(5):271.

63. Takahashi, K, Iwase, M, Yamashita, K, et al. The elevation of natural killer cell activity induced by laughter in a crossover designed study. Int J Mol Med. 2001;8(6):645.

64. Taylor, LPS, McGruder, JE. The meaning of sea kayaking for persons with spinal cord injuries. Am J Occup Ther. 1996;50(1):39.

65. Trenberth, L. The role, nature and purpose of leisure and its contribution to individual development and well-being. Br J Guidance Counseling. 2005;33(1):1.

66. Trenberth, L, Dewe, P. An exploration of the role of leisure in coping with work related stress using sequential tree analysis. Br J Guidance Counseling. 2005;33(1):101.

67. Vergeer, G, MacRae, A. Therapeutic use of humor in occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 1993;47:678.

68. Warren B, ed. Using the creative arts in therapy and healthcare: a practical introduction, ed 3, New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2008.

69. Wikström, I, Book, C, Jacobsson, LT. Leisure activities in rheumatoid arthritis: change after disease onset and associated factors. Br J Occup Ther. 2001;64(2):87.