Performance Skills

Definitions and Evaluation in the Context of the Occupational Therapy Framework

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Describe the difference between a performance skill and a client factor.

2 Explain client-centered occupation-based performance.

3 Relate how improvements in performance skills may influence habits, roles, and routines.

4 Define impairment, strategy, and function.

5 Identify principles that may affect client outcomes.

6 Explain how a skilled intervention with clients facilitates cortical reorganization.

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-2

The revised Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-2 (OTPF-2) was designed to guide occupational therapy practice and to convey to others the complexity of the profession.1 The revisions were offered to “refine the document and include language and concepts relevant to current and emerging occupational therapy practice” (p. 625). This chapter will review the connection of performance skills and client factors as applied to a client case presentation.

Connection of Performance Skills and Client Factors With Occupational Performance

Performance skills and client factors influence a client’s occupational performance. Occupational performance is engagement in meaningful and purposeful activities that relate to habits, routines, and roles. Active client engagement in occupation-based evaluation and intervention can facilitate changes in performance skills and performance patterns, which may influence habits, roles, and routines, and ultimately occupational performance. This chapter will address how these elements relate to any client throughout the lifespan and will describe how neuroscientific research suggests that an occupation-based approach can facilitate changes in the central nervous system that directly correlate with improvements in occupational performance and client-centered outcomes.

The importance of client-centered interactions in the selection of specific occupations as a means to helping clients progress through the occupational therapy (OT) process is a concept endorsed by the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA)1 and several leaders in the OT profession.7,9,16,24 This process may occur in various ways—via the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS),7 an occupational functioning model,24 or a task-oriented approach16; in all cases, the message is similar. Analysis of client performance provides the OT practitioner with a means by which to understand what is observed. These authors identify with a common thread consistent with the World Health Organization definition and classification of disability26: that performance analysis is important. This analysis may be formal or informal. One particular caution is to make sure that during any informal analysis, the intended outcome is specifically identified. This will allow the OT practitioner to anchor what was expected with what is actually performed and observed. Thus, the focus remains on the tasks and corresponding performance skills; the client factor does not serve as the key determining variable in the OT process.

Occupation-Based Approaches and Neuroscientific Evidence

Connecting occupation-based approaches to the neuroscientific realm provides a framework by which to consider these concepts as they relate to learning. Learning, as defined in this context, theoretically occurs as a result of neuroplasticity, and it is assumed that new neuronal connections and axonal sprouting occur within the central nervous system through multisensory input.23 Application of this concept may be seen with clients who have sustained upper motor neuron (UMN) injuries. Current trends in occupational therapy to ameliorate upper extremity hemiparesis as a result of UMN lesions are varied, yet research indicates that a potentially beneficial way to achieve a successful client-centered outcome is to include those interventions that address how the client interacts with the task and the environment.25 This particular approach is supported by basic and applied neuroscience concepts that imply that skilled interaction associated with a client’s task performance in a particular environment may direct cortical changes and facilitate neuromuscular recovery. Consequently, this type of approach may improve completion of activities of daily living (ADLs) by improving performance skills11 via engagement in occupational performance–based activities. Occupational performance, as such, often is observed when a person performs a particular task in a particular environment.27 This dynamic interaction among the individual, the task, and the environment is consistent with the foundational framework provided by the task-oriented approach (TOA).16

The TOA is one of a variety of approaches to evaluation and intervention that incorporates an underlying understanding of a variety of concepts. Among these is the ecologic approach to the performance of functional tasks (and purposeful movements). This approach emphasizes interactions among the person, the environment, and task performance.16 The term task is not equivalent to occupation.7 Although several definitions of the term occupation have been offered, the elements that distinguish occupations from tasks include the specific meaning to the occupational performance and the occupational performance within a context or environment.6 A task is often a small portion of an occupation, such as the task of cutting with a knife and fork within the occupation of self-feeding. Yet an appreciation for the task-oriented approach is associated with an understanding of the potential impact that the task may have upon occupational engagement. The OT practitioner may apply motor learning concepts and may adapt, modify, or otherwise facilitate successful completion of an occupation-based goal.

Application of the TOA directs occupational therapy practitioners to address the performance skill11 deficits of clients while simultaneously incorporating current understanding of neuroscientific concepts. Both the process and the outcome are important in this approach. The net result of this approach is that the client may benefit through improved performance of ADLs. Ultimately, this may support the practice of habits and routines and eventually may facilitate a return to desired, client-centered roles.

Performance Skills and Client Factors

The OTPF-2 identifies client factors and performance skills as separate elements and describes how they impact and are impacted by client interaction with the task and the environment in the performance of ADLs.1 Fisher provides a background on the process of how to formally and informally assess performance skills and patterns in relation to occupations.7 She states that to understand how client factors influence occupational performance, it is important to thoroughly determine how these components affect performance skills during occupational performance.7 Thus, it could be inferred that any attempt to assess this relationship without an appreciation for and an understanding of this dynamic process may lead to potentially “misdirected” conclusions. In other words, the OT practitioner may make clinical decisions that are not in the best interests of the client and will not reflect “best practice.”

Table 18-1 identifies performance skills from the OTPF-2.

TABLE 18-1

| Performance Skills | Definition |

| Sensory perceptual skills | The ability to receive sensory information and interpret that information while engaged in occupational performance. |

| Motor and praxis skills | The skilled motor behaviors displayed by the individual in interacting with objects, tasks, and environments while engaged in occupational performance.7 |

| Emotional regulation skills | The client’s ability to express, manage, and identify feelings while engaged in occupational performance. |

| Cognitive skills | The ability of the client to plan, organize, and monitor occupational performance. |

| Communication and social skills | The client’s actions and behaviors in communicating and interacting with others.7 |

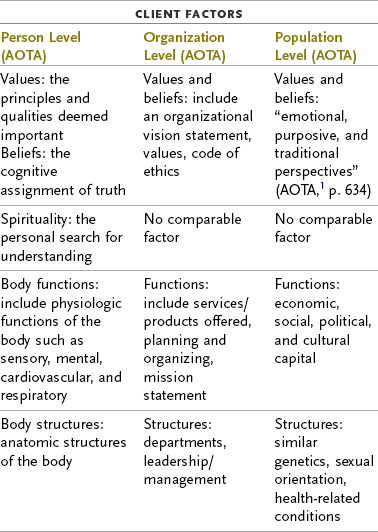

Table 18-2 identifies client factors from the OTPF-2.

In what way can the occupational therapy practitioner evaluate John to identify what assets and deficits this client may be able to utilize?

It is necessary to understand current client abilities relative to specified task performance. This can be done by measuring particular client factors such as John’s left upper limb active range of motion (ROM) and strength. As discussed in the chapter, it is important to have an understanding of particular areas of deficit before initiating occupational therapy services. This understanding should be combined with observations of John’s participation in certain activities, which may include performance of his morning routine such as dressing, brushing teeth, and shaving. The OT practitioner would observe what specific strategies are utilized. If John turned his body to the side to position his left arm across his lap to then place his left arm into the sleeve of a shirt, it is likely that this particular strategy maximizes his performance skill. The evaluation process would be a combination of client factor measurement with occupational performance assessment, which would most likely reflect John’s abilities to perform these ADLs.

Client factors related to body and structure function are important because they inform the OT process and ultimately contribute to an understanding of how these functions (or lack thereof) contribute to the evaluation process and the development of an intervention plan. Additionally, values, beliefs, and spirituality are included as client factors in the OTPF-2.1 Within the OTPF-2,1 client factors are differentiated at the person, organization, and population levels; this chapter will primarily address client factors applied at the level of the person. Specific client factors identified at the level of the person may include neuromusculoskeletal functions related to strength, muscle tone, motor reflexes, and voluntary and/or involuntary movement. Global and specific mental functions are important client factors that support incorporation of input gained by one’s interaction with a task within the environment. These mental functions, collectively termed cognition, are required for a person to make sense of sensorimotor input from the environment. They are important to overall functional ability. Also, the degree to which the central nervous system is intact following damage or the appearance of a lesion will affect a client’s occupational performance.

As they relate to UMN cortical lesions, these client factors may result in peripheral soft tissue changes, hypertonia, spasticity, and changes in range of motion. Any combination of these changes will likely influence how a client participates in a particular task. These client factors remain relevant and supportive in their role in the overall OT process. In other words, they are a means to understanding an end that focuses on performance skills, as these skills support the performance of occupations.

Client factors differ from performance skills in that they represent responses to system control. Client factors often can be measured and quantified and include strength, range of motion, visual acuity, muscle tone, and attention. Client factors represent bodily functions and what the “body” does, rather than what the “person” does. This distinction is made clear by Fisher,7 who stated that client factors are the actual body structures and basic body functions. Additionally, client factors represent what a person can utilize to perform a particular task. Thus, client factors facilitate performance skills, but merely assessing available client factors is not predictive of occupational performance.1

Performance skills include the motor and praxis, sensory-perceptual, emotional regulation, and cognitive and communication/social skills required to perform specific tasks (i.e., ADLs, instrumental ADLs [IADLs], and work). Fisher7 described performance skills as “small units of action [that] are always goal-directed because they are enacted in the context of carrying out and completing a daily life task” (p. 375). Therefore, performance skills are not assessed in the absence of occupational performance but must be assessed while the client is engaged in an occupation. For example, John would like to be able to prepare a dinner that includes cooking on the stove, specifically, cooking pasta and spaghetti sauce. Although assessment of specific body functions may reveal limited isolated active range of motion (AROM) of his left arm, making it difficult for him to hold the handle of the sauce pan while stirring the sauce with his right hand, during the actual task performance, the OT practitioner would also note difficulties in positioning his body appropriately to the stove and poor pacing of actions in the performance skill categories of sensory-perceptual and motor and praxis skills. Motor and praxis skills along with sensory-perceptual skills are required in adequate and appropriate amounts for an individual to interact with an object in the environment during performance of a task in an accurate and efficient manner. This process can be dynamic and complex, and understanding this interaction informs and directs the OT evaluation and intervention. The ability to judge and respond to task demands is an aspect of cognitive performance skills linked to overall occupational performance. If John were to cook pasta and spaghetti sauce for dinner, he would have to sequence the task appropriately by starting spaghetti sauce, then placing water on the stove for the pasta, and, as the sauce simmers, adding pasta to the boiling water. He would need to time all these events appropriately to avoid serving cold pasta with overcooked sauce. Given John’s difficulties in attention (a client factor), an OT practitioner may assume that the complex task of cooking spaghetti and sauce would be a challenge. Without observing the actual performance, the therapist may have suggested a checklist as an intervention method without understanding how the sensory-perceptual and motor and praxis performance skills interact with cognitive skills during the occupation of meal preparation. Thus, a person presents with specific deficits (client factors) that affect performance skills, and this may affect occupational performance.

Significant changes/impairments with these client factors may sufficiently influence a client’s performance patterns and skills and eventually (adversely) may influence occupational roles. Research indicates that the TOA is more likely to positively influence outcomes when compared with treatment that addresses only client factors.19 Neuroscientific research is pointing toward the possibility that the central nervous system is organized in such a way that tasks can be addressed through interaction with the environment rather than with specific muscle groups meant to perform specific tasks. This is consistent with the TOA. Thus, understanding of a client’s roles and routines will guide an OT practitioner’s ability to address performance skills as they relate to occupational performance. In summary, performance skills are required for interaction with task, object, and environment.20

How would John benefit most from occupational therapy intervention with a focus on performance skills to support improvements in client-chosen activities?

John is motivated to improve his self-care and home management skills. He is able to complete his morning routine and self-care activities with limited physical assistance from another person. He has a supportive family that provides assistance as needed. He stated that he wants to be able to improve his ability to complete his morning routine, self-care activities, and home management tasks. If the OT practitioner were to focus on prioritizing these activities, it would be possible to determine the best way to address reacquisition of these abilities. Although multiple control parameters (a control parameter refers to the motor element that influences performance) can influence successful task completion, it is likely that in any particular activity, at least one key parameter may be the most limiting factor to successful task completion. For example, with the shaving activity, John’s impaired movement in his left hand compromises bilateral task performance and serves as the control parameter. This impairment, as described in the case illustration, is a result of the inability to have sufficient distal control. It is important to observe the actual performance of the shaving activity when possible to avoid any contrived situations. Merely having John use a safety razor with the cover in place to simulate the act of shaving would not accurately replicate the actual performance of shaving. In this instance, it needs to be determined whether focusing on how the performance skill of bilateral control can be achieved will improve shaving, or if the task needs to be adapted to maximize independence. The OT practitioner can validate these approaches by observing John during the actual task of shaving. This same approach may be taken with each activity to be addressed.

Motor Control Theory

Interaction among the task, the person, and the environment represents important aspects of motor control. Motor control theory, that is, the ability to make dynamic changes in/responses of body and limb to complete a purposeful activity,23 has undergone much development in recent years. This development has expanded our knowledge base, has answered some questions, has introduced other questions, and has permitted a greater appreciation than ever of the complexity of cortical function as it relates to motor performance.

A variety of sources indicate that multisensory input will provide the nervous system with input, which ultimately will lead to improved quality of movement performance and decreased error, and will support more efficient movement patterns.4,18,19 These multiple sensory inputs to learning (or relearning), whether intact or not intact, will work together to contribute to our understanding of interaction with the environment. When one sensory input (or system) is impaired, others may need to compensate. When one part of a system is impaired, the performance pattern is affected. For example, if a person presents with impaired ability to perform dynamic distal (hand and finger) movements as the result of decreased motor control, then he or she may move the proximal upper limb in such a manner as to compensate for this impairment.17 The net result of this compensatory movement may present as “shoulder hiking” and may include other movements such as lateral trunk flexion or even shortening of the lever arm (i.e., elbow flexion) to control degrees of freedom.22

John likely “hikes” (abnormally elevates) his left shoulder when movement is initiated as he attempts to reach for objects such as his razor or toothbrush. Doing so allows him to be able to get his left arm to a position from which he can access these items. John may be aware of the fact that he might have reached differently before the CVA. The OT practitioner may ask John to reach for these items with his right hand for comparison (recall that John is right hand dominant). This serves as an informal task analysis. If the position of the items and how John interacts with the objects in the environment are changed, analysis reveals how this may affect the strategy, given available skills.

It is possible that this inefficient movement pattern could be repeated and might eventually develop into a new adapted or maladapted pattern. Unless this process is properly analyzed, the client is more likely to “learn” and repeatedly use this inefficient movement pattern to accomplish a task. Poor and ineffective patterns may emerge, overuse syndromes may occur, and the net result is potentially poor self-efficacy with occupational performance.

Repetition alone as part of a neuromuscular rehabilitation approach is insufficient to create and reinforce cortical reorganization.2,11,22 This statement is neither novel nor ground-breaking in its meaning, yet its intent is shared by multiple researchers in a variety of arenas from basic neuroscience to the field of occupational therapy.2,11,12,18 It is a well-established hallmark of occupational therapy to develop an occupational profile and to engage the client in meaningful and purposeful activities. Additionally, intense task-oriented training of the sensorimotor cortex is believed to lead to cortical reorganization. Bayona and associates reported that rehabilitation outcomes have greater success when the tasks are meaningful to the patient.2 Volpe and colleagues reached this same conclusion.25

Client-centered, therapist-driven, task-oriented approaches may not directly translate to anecdotal or clinically measurable/significant before and after changes. Motor learning concepts25 indicate that the degree to which a task is learned is positively correlated with the “depth” of the “well” in which it is kept. In other words, the more ingrained a task is to a person, the more challenging it may be to change, or transition, the movement or behavior. The key point at which this transition occurs may also be influenced by control parameters.

Control parameter is a motor control term that pertains to anything that shifts a motor behavior from one manner of performance to another type of performance. Control parameters can be internal to the person (such as strength, vision, for example, John’s left visual field deficit) or external (such as location of an object, lighting). Consider the task of washing your back; the length of your arm, the size of your back, and established habits from training all serve as control parameters. Do you attempt to wash your left scapular area with your right or left hand? When the control parameter is a client factor, the occupational therapy practitioner may attempt to address/remediate the client factor.16 This approach to the OT process, often termed a “bottom-up” approach, assumes that addressing the fundamental client factors will allow the OT practitioner to interact with the client to improve the client’s occupational performance. Yet doing so may not translate to improved performance skills or occupational performance. In fact, it is likely that the further the intervention for the client factor is from the actual occupational activity, the less likely it is that there will be a positive correlation between these two items. Ultimately, the degree to which the client factor is impaired will affect the end result and compensatory or adaptive interventions provided by the OT practitioner to the client.

These concepts could provide at least part of the explanation as to why improvements have been measured as clinical outcomes in some well-developed studies in this arena, although limited long-term improvements have been noted. Consequently, it may be challenging to overcome (sometimes poorly) practiced performance skills and patterns. Return to the example of John cooking dinner. He has a left visual field cut, which compromises his ability to obtain visual information, and when the pot with pasta (located on the left side of the stove) begins to boil over, John is not receiving that visual input. He could be trained to visually scan the environment to compensate for the visual field cut; it would be most appropriate to provide this training within a natural environment and with preferred occupations.

Fundamentals of experience-driven neuroplasticity include the adaptive capacity of the central nervous system to make fundamental changes and alterations on the cellular and eventually the systems level, which can lead to new learned/adapted behaviors. Key critical “signals” can facilitate such recovery.12 Additionally, the brain continually reorganizes itself, with or without damage.10,12 This process of learning will occur spontaneously, with no explicit learning or formal rehabilitation. Lack of skilled therapeutic intervention may lead to maladaptive behavioral responses. It is skilled learning that occurs through the use of strategies and adaptations to facilitate this adaptive response. This has been shown to occur with the use of the TOA and task-specific techniques. Focus on the performance skill in therapy allows the opportunity for skilled learning to occur. A person may present with compensatory movements or adaptations to control parameters such as decreased agonist strength. The TOA, with a focus on the person interacting with the task in the environment, can address this limiting performance client factor (compensation), in part by guiding the performance skill via skilled management of the dynamic interaction of these items. Compensatory behavioral changes are a regular part of this process.12

John has been attempting to move his left arm as much as possible since the CVA. He tells family and caregivers frequently that he wants to do as much as possible for himself. He is motivated to make improvements. When he attempts to complete self-care activities on his own, he does not make adjustments in the environment. He interacts with objects with poor movement patterns. His performance skills are relative to how he uses objects. The OT practitioner can maximize the quality of the performance skills with a focus on how John brushes his teeth or shaves. This would serve as the foundation for how to modify the task or the environment.

Kleim and Jones12 identified 10 principles that fit this process: (1) use it or lose it, (2) use it and improve it, (3) specificity, (4) repetition matters, (5) intensity matters, (6) time matters, (7) salience matters, (8) age matters, (9) transference, and (10) interference. These principles come from basic and applied neuroscience research concepts, which have shown that they can influence outcomes. These principles can support evaluation and treatment.

Effective evaluation of the client who presents with upper limb hemiparesis, as has been described in this chapter, should be based on a thorough understanding of the specific impairments (client factors) that affect the performance of occupation-based, client-centered tasks. Although specific client factors may be addressed as part of treatment, this may not necessarily reflect changes in occupational performance. A client may need to improve biceps strength to complete a hand-to-mouth pattern, yet improving biceps strength to a point where the strength is sufficient to facilitate the movement does not guarantee that the task can be completed successfully. Thus, the focus should be on the performance skills and patterns. Observation of the client strategy with use of remaining abilities as it relates to overall function is an important part of the evaluation process. This should occur with respect for current understanding of how skilled interventions by the occupational therapy practitioner may direct learning/relearning and lead to neuroplastic cortical changes. These changes in performance skills can lead to improvements in occupational performance.

Comprehensive evaluation with respect for the TOA requires a thorough assessment of impairment, strategy, and function. As stated earlier in this chapter, the specific impairments are those that occur as a consequence of the UMN lesion. These impairments may include but are not limited to weakness (of the agonist), decreased coordination, decreased in-hand manipulation, inability to manage agonist and agonist efficiently, impaired/absent sensation, proprioception, impaired vision, and decreased overall cognitive ability. These impairments may be measured via traditional OT assessment approaches such as manual muscle testing, range-of-motion testing, sensation testing, vision testing, strength (grip) testing (e.g., via a dynamometer), coordination testing (e.g., via the Nine Hole Peg Test), and so on. The appropriate standardized test may be determined in part by the site/setting. The benefit of these assessments is that they provide a pretest foundation from which to measure progress. Yet, these client factors remain relevant in so much as they influence occupational performance via performance skills. Thus, it is important for the OT practitioner to have an appreciation of the strategies and performance patterns utilized by the client.

John has less than five pounds of grip strength in his left hand as measured by the dynamometer. He has impaired sensation of the dorsal aspect of his left hand. He does not visually attend to the environment in his left peripheral visual field. These are client factors. John grasps onto objects such as eating utensils with insufficient strength when he attempts to use his left hand to hold a fork while cutting foods with the knife in his right hand. He is unable to judge the water temperature from a faucet on his left hand before shaving. He does not always attend to the left side of his environment when he is attempting to cook. These are performance skills. He requires assistance and verbal cues to complete his morning routine with good quality. This is occupational performance.

Ultimately, it is the occupational performance that arises from performance skills and patterns supported by clinical observations and leads to clinical decisions for “best practice.” The benefit derived from use of the TOA with respect for current neuroscientific concepts such as cortical neuroplasticity is that the OT practitioner addresses a client’s needs from a “top-down” approach rather than from a “bottom-up” approach. The top-down approach directs the OT practitioner to work with the client from the view of actual occupational performance. Fisher7 described these approaches, along with the benefits and potential pitfalls of each. It is possible to complete the impairment-based measurements and progress to function or to start with functional performance and to utilize these observations to guide assessment and treatment, yet caution is suggested when a “motor behavior perspective”7 is solely utilized.

John has decreased strength and range of motion throughout his left upper limb. This impairment is observable and measurable. Sole measurement of these items is insufficient to create a client-centered occupation-based treatment plan. It might be possible to measure these client factors. Improvement in strength or range of motion may not reflect improvement in John’s ability to raise his left arm to apply shaving cream to his face. It is important for the OT to understand deficits as they relate to real performance through some client-identified, clinician-driven approach.

Neuroscience Research Related to Practice

Recent research relating neuroscientific concepts from the animal model (rodent and primate) to the human model provides evidence of the potential benefit of providing skilled learning opportunities to direct cortical reorganization.18,19,21 Cortical reorganization is the concept that the adult brain has a neuroplastic ability to alter or modify its synaptic connections in the context of performance of a skilled activity—whether or not the brain and the central nervous system are intact. Nudo and coworkers18,19 completed ground-breaking research, which demonstrated that by applying skilled learning principles, it is possible to create topographic cortical map changes that directly correspond to specific “pellet retrieval” (distal forelimb) tasks after focally induced cortical lesions appear in these particular representative areas in squirrel monkeys. Task-specific training can lead to increased cortical representation of the trained areas, along with decreased representation of the previously post-infarct compensatory areas. The net result of acquiring performance skills in these primates was improved quality of movement. Most of the “improved performance patterns” occurred via observation and interpretation of behavior by the researcher before and after intervention assessment. This demonstrates the ability of the cortical region to reorganize when demands are placed upon it to function. Of course the process of reorganization is limited, particularly if large sections of the cortex are damaged.

It has been suggested that the OT practitioner should apply these principles from the animal models with caution, because some variables remain to be clarified. Animal (primate) model research in this area has provided invaluable information, yet these conclusions have resulted from specific, focally induced lesions21 with clear boundaries as to the lesioned areas. In many instances, adjacent tissue is undamaged.21 In humans, research has demonstrated that peri-infarct (cortical) reorganization may occur. Additionally, in humans, the “edges” of the lesioned area are not always clear.21 Aside from the clinical implications of these variances, other potential issues may arise from more complex cortical damage. These may include medical complexity, family/caregiver support, comorbidity, cultural expectations, or other client-specific variables. These challenges have not been the focus of study, nor have they been addressed, in the animal model.

What would be the best fit for treatment interventions to facilitate occupational performance for John, given the current available evidence and understanding of neuroscience?

Current research indicates that it may be most beneficial to observe how John participates in particular daily activities. This allows the OT practitioner to understand what repeated behaviors are used and where new strategies may be effective in assisting John in his desired occupational outcomes. Through this approach, it may be possible for the OT to better fit treatment to John’s needs. This also allows the possibility to focus on activities that are of interest to John and to apply concepts related to the task-oriented approach (TOA). This approach is both client centered and occupation based. Specific treatment activities will focus on matching the client performance patterns.

Data from both animal and human models point to the likelihood that client-centered, client-specific intervention plans and approaches may constitute “best practice.” This, of course, may introduce challenges regarding how to implement such approaches into the current standard of care. Regardless, the distinction between animal and human models likely will continue to be a topic of discussion. This discussion is relevant when we attempt to consider what defines the aforementioned “best practice.” Birkenmeier and associates3 attempted to address this translation from neuroscientific concepts to animal model research to clinical research implementation. Their description of how they made these decisions is one of the most comprehensive presentations on this issue.

The Northstar Neuroscience Phase III Clinical Trial14 has taken these neuroplastic concepts and knowledge from animal models and applied them to a treatment protocol based on occupational therapy concepts of client-centeredness. This randomized controlled trial included nearly 150 subjects from close to 20 sites. The study was undertaken to investigate the potential benefits of subthreshold cortical stimulation in combination with “skilled” (already defined in this chapter) learning via a therapy protocol grounded in the TOA. Similar investigations have identified benefits that may be derived from subthreshold (i.e., nonevoked potentials) cortical stimulation to support synaptic connections and dendritic density, and to facilitate overall cortical reorganization.21 Although the exact dosage of the stimulation and whether or not specific cortical stimulation to the region responsible for post-lesion upper limb (distal) control or another approach such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) remain unclear at this time, this area offers potential future benefit.21

The treatment protocol for the Northstar Neuroscience Phase III Clinical Trial14 incorporated the approach of evaluation (and corresponding intervention) of impairment, strategy, and function within the realm of the TOA. The impairment corresponds to the client factor. The strategy corresponds to how the person attempts to perform a task as it relates to occupation, given specific impairments. Function corresponds to how the impairment and corresponding strategy relate to performance skills and patterns. Ultimately, subjects in this clinical trial were evaluated and treated within this framework.

Research therapists evaluated and treated subjects with a focus on performance skills. This focus arose from client-centered occupation-based tasks that were determined for each participant via the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM).15 Clients’ self-perceived changes in performance patterns for ADLs were measured by the COPM. Other assessments utilized as outcome measures included the Fugl-Meyer8 and the Arm Motor Ability Test.13 These latter two are well established, and validated clinical measures were primary outcome measures for this particular study. Clients demonstrated improvement in COPM outcome measures, but significant changes were not noted on the other two measures. Evaluation of clients was carried out according to the principles outlined by the TOA. Treating therapists were trained and followed standardized procedures to focus with the client on client-centered goals. Once an individual improved on a client factor or performance skill, the treating therapist reviewed how that change affected the performance pattern and what this represented in terms of occupational performance. Changes in performance skills noted among participants in this study—addressed through utilization of client-centered functional activities focused on the use of strategies related to task performance—corresponded to changes in client factors. This treatment approach and protocol are consistent with neuroscience concepts of skilled learning supporting cortical changes that may lead to changes (improvements) in occupational performance, performance patterns, habits, routines, and roles. A portion of this protocol included evaluation and understanding of the impact of client factors upon performance skills.

Muscle strength, range of motion, sensation, and a variety of other client factors are necessary to engage in functional activities and therefore are important to measure in a quantifiable manner. An adequate amount of strength, for example, is necessary to grip an eating utensil, and sufficient active range of motion is necessary to complete a hand-to-mouth pattern. Yet the key with this protocol was that neuroplastic concepts were used to link client factors to performance skills to facilitate adaptive plasticity. Isolated work on the client factors of muscle strength and range of motion was not part of the protocol. Adaptive plasticity (the innate ability of the central nervous system to adapt or modify behavioral responses after exposure to a challenge to the system) implies that by addressing the performance skill, direct change toward improved quality of occupational performance will occur. As defined, the performance skill occurs in the process of engaging in the occupation and cannot be separated from the occupation.

The examples provided in this chapter reflect neuroscientific knowledge as it relates to how OT practitioners work with the neurologically impaired client; these same fundamental concepts can guide clinical interventions with a variety of other clients across the lifespan.

Although the approach discussed in this chapter may relate to any client, a few other examples have been provided for consideration. This list is not exhaustive. For the sake of this chapter, the focus is on adults. For example, a client who has cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), total knee replacement (TKR), or Parkinson’s disease may benefit from the approach discussed in this chapter. The condition will inform the OT practitioner as to origin, clinical and medical presentations, prognosis, and other valuable information. Client factors affected by any condition, such as the ones previously listed, may influence performance skills and possibly performance patterns. Ultimately, this leads to the possibility that habits, routines, and roles may also be affected. Observation and assessment of performance skills may still guide the OT practitioner to a client-centered occupation-based intervention.

John has sustained a right MCA CVA. This condition informs the OT practitioner that he is likely to have left upper limb motor impairment. Additionally, other consequences may result from the CVA. John may have decreased attention and decreased visual attention to the left side. It is important to be aware that John is also a parent and a housekeeper. He wants to return to these roles. Thus, mere measurement of the specific client factors that have resulted from the CVA will not explicitly return him to these roles and routines.

The older client with the TKR may present with decreased bilateral upper extremity strength, not as a result of the TKR but because of deconditioning from diminished activity secondary to knee problems. This decreased bilateral upper extremity strength will limit the ability to efficiently utilize a walker for functional mobility around the home. This client may also have a history of cognitive impairments that affect the ability to learn new concepts. The OT practitioner may have to consider these items in developing a client-centered intervention plan. The framework provided in this chapter indicates that the OT practitioner will likely assess upper limb strength and range of motion. The OT intervention may even include exercises and activities that may improve these client factors. Yet this does not mean that in doing so, the client will improve the performance skill involved in, for example, a morning routine. Nor does it imply that engaging a client in a purposeful activity will translate to improved occupational performance. How a task is practiced in the clinic may not translate to the home environment. Thus, the formal or informal occupational profile and analysis will provide the foundation from which the OT practitioner may link current status to desired outcomes.

Best Practice Occupational Therapy Service

It is important to bring this discussion back to clients who have acquired neurologic deficits to identify how this particular group of clients can best be treated by occupational therapy practitioners. As occupational therapy practice for the adult neurologic practice moves further from an “expert opinion” approach and toward one that is grounded in evidence (whether that evidence supports or refutes traditional practice approaches), much more remains to be learned to determine “best practice.” Attempts have been made to pinpoint both current trends and task-specific training to identify what defines “best practice.” In support of this comment, Carter and colleagues5 described that much of the effort in rehabilitation research is going in the direction of “motor restoration.” Additionally, they stated that the quality of the research is more rigorous than it has ever been in the past.

When it comes to measuring performance and improvements in clients with neuro-insults, it may be true that previous outcome measures used to identify improvements are insufficient at this point in time. For example, some standardized and validated measures that address activities of daily living do so with contrived ADLs. Contrived activities are those that are artificially created often in an attempt to re-create real scenarios. Although potential benefits may be derived from using a standardized ADL assessment as a common, consistent approach to measuring performance and conveying performance information that is clearly recognized because of the standardization process, if this standardized process lacks the fundamental elements of the task or is too “contrived,” it may affect performance and corresponding measurement of performance. An example of a contrived situation would involve a client “spreading” butter on bread by using a knife on a plate in the spreading motion without the actual bread or butter. In this example, the client may possess the motor control needed for the task, but in the actual task (real-world experience) of spreading butter on the bread, the client may fail to notice that all the butter is located on one corner of the bread, or may use excessive force and tear the bread. These observations would not be possible with a contrived activity but would be immediately noticed if the client is given an actual piece of bread and butter. Wu and coworkers28 described that “real” performance of activities leads to different and “better” results than are attained through imagined or contrived activities. Additionally, a variety of means can be used to measure performance, including time to complete portions of a task, time to complete the entire task, and subjective observations of quality of performance. Further research may advance newer ways to measure performance skills and occupational performance. This does not mean that we, as occupational therapy practitioners, should not attempt to incorporate current trends, concepts, measures/assessments, and techniques.

Other considerations pertain to the impact of how we intervene with clients such as John. Timing, dosage, and method of delivery are important variables needing control in clinical studies, and these variables should also be considered in clinical practice. Although evidence-based practice is expected, using data from an investigation that did not attempt to control these factors needs to be considered with some caution.5 Given the competition for space in the cortex after UMN damage,16 it is necessary for OT practitioners to respond immediately and effectively to client needs. This clinical reasoning process may affect how performance “plateaus” are determined in clinical practice.

Plateau is a term that is all too common in the realm of current rehabilitation practice with persons with upper limb hemiparesis, as well as other conditions across the lifespan. Page and associates20 suggested that the way in which therapists frame the upper limb hemiparetic population may need to be reconsidered. They stated that what defines (1) motor recovery plateau, (2) ability to recover motor function, and (3) when to use different modalities may have to be reconsidered. “Traditional” expectations of most (motor) recovery occurring in 6 to 12 months often guide insurance and are tied into clinical practice. This chapter identifies the reasons why this may not necessarily be the case.

Immediately after a CVA, some clients may be able to participate in a rehabilitative program designed to foster self-care skills, but other clients may be far too ill. The timing, intensity (dosage), and method of delivery for these two clients most likely will vary, but a similar functional outcome may ultimately be met. Hubbard and colleagues11 summarized principles that should be considered for incorporation of task-specific interventions. These suggestions may serve as a guide for “best practice,” while addressing the potential for improvement in performance skills. They suggested that such training/intervention should “be relevant to the patient/client and to the context; be randomly assigned; be repetitive and involve massed practice; aim toward[s] reconstruction of the whole task; and be reinforced with positive and timely feedback.”11 They further concluded that although, as noted in this chapter, much evidence points toward the benefit of task-oriented or task-specific training techniques, “common” practice approaches are grounded in “accepted practice or custom” and may be beneficial at specific points in time. An appreciation for this conclusion and the current state of neuroscience as it relates to this population can serve to transform clinical practice. Given the complexity of human beings, what emerges as “best practice” may incorporate a multifactorial approach to guide client-centered evaluation and treatment, maximize outcomes, and facilitate client habits, routines, and roles.

Summary

It is possible to address client-centered, occupation-based needs with a focus on performance skills. Neuroscientific research indicates that this approach can be applied with the use of certain approaches such as the TOA. The TOA emphasizes a dynamic interaction between the person, the task, and the environment. OT practitioners are trained and able to address control parameters and complete performance analyses to maximize overall occupational performance.

1. What are the advantages of using “real situations” instead of “contrived situations” when assessing clients?

2. What are the advantages of using “contrived situations” instead of “real situations” when assessing clients?

3. What does the term plateau mean in reference to clients who have sustained neurologic insults?

4. What is the difference between a client factor and a performance skill?

5. Using the task of brushing your teeth as part of your morning routine, identify two client factors and two performance skills that influence engaging in this task.

6. What does the term control parameter mean in working with clients who have sustained neurologic insults?

7. Explain the term neuroplasticity.

8. Explain the term cortical reorganization.

9. How do the terms neuroplasticity and cortical reorganization support occupation-based interventions?

References

1. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process, 2nd edition. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62:625–683.

2. Bayona, NA, Bitensky, J, Salter, K, Teasell, R. The role of task-specific training in rehabilitation therapies. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2005;12:58–65.

3. Birkenmeier, RL, Prager, EM, Lang, CE. Translating animal doses of task-specific training to people with chronic stroke in 1-hour therapy sessions: a proof-of-concept study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;20:1–16.

4. Carr, J, Shepherd, R. The adaptive system: plasticity and recovery. In: Carr J, Shepherd R, eds. Neurological rehabilitation: optimizing motor performance. ed 2. Oxford, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:3–14.

5. Carter, AR, Connor, LT, Dromerick, AW. Rehabilitation after stroke: current state of the science. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:158–166.

6. Dickie, V. What is occupation? In: Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Schell BAB, eds. Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy. ed 11. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:15–21.

7. Fisher, A. Overview of performance skills and client factors. In: Pendleton H, Schultz-Krohn W, eds. Pedretti’s occupational therapy for physical dysfunction. ed 6. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2006:372–402.

8. Fugl-Meyer, AR, Jääskö, L, Leyman, I, et al. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient: a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7:13–31.

9. Gillen, G. Stroke rehabilitation: a functional approach. St Louis, Mo: Elsevier; 2011.

10. Hebb, DO. The organization of behavior: a neuropsychological theory. New York: Wiley; 1949.

11. Hubbard, IJ, Parsons, MW, Neilson, C, Carey, LM. Task-specific training: evidence for translation to clinical practice. Occup Ther Int. 2009;16:175–189.

12. Kleim, JA, Jones, TA. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:S225–S239.

13. Kopp, B, Kunkel, A, Flor, H, et al. The Arm Motor Ability Test: reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of an instrument for assessing disabilities in activities of daily living. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:615–620.

14. Kovic M, Stoykov ME: A multi-site study for cortical stimulation and occupational therapy. Presented at: 15th Congress for the World Federation of Occupational Therapists, May 2010, Santiago, Chile.

15. Law, M, Baptiste, S, Carswell, A, et al. Canadian occupational performance measures, ed 3. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 1998.

16. Mathiowetz, V. Task-oriented approach to stroke rehabilitation. In: Gillen G, ed. Stroke rehabilitation: a function-based approach. ed 3. St Louis: Mosby; 2011:80–99.

17. Muellbacher, W, Richards, C, Ziemann, U, et al. Improving hand function in chronic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1278–1282.

18. Nudo, RJ, Milliken, GW. Reorganization of movement representations in primary motor cortex following focal ischemic infarcts in adult squirrel monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2144–2149.

19. Nudo, RJ, Milliken, GW, Jenkins, WM, Merzenich, MM. Use-dependent alterations of movement representations in primary motor cortex of adult squirrel monkeys. J Neurosci. 1996;16:785–807.

20. Page, SJ, Gater, DR, Bach-Y-Rita, P. Reconsidering the motor recovery plateau in stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1377–1381.

21. Plow, EB, Carey, JR, Nudo, RJ, Pascual-Leone, A. Invasive cortical stimulation to promote recovery of function after stroke: a critical appraisal. Stroke. 2009;40:1926–1931.

22. Rossini, PM, Calautti, C, Pauri, F, Baron, JC. Post-stroke plastic reorganisation in the adult brain. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:493–502.

23. Shumway-Cook, A, Woollacott, MH. Motor control: translating research into clinical practice, ed 3. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

24. Trombly, CA. Occupation: purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms. Am J Occup Ther. 1995;49:960–972.

25. Volpe, BT, Lynch, D, Ferraro, M, et al. Intensive sensorimotor arm training improves hemiparesis in patients with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22:305–310.

26. World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability, and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

27. Wu, C, Trombly, CA, Lin, K, Tickle-Degnen, L. Effects of object affordances on reaching performance in persons with and without cerebrovascular accident. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52:447–456.

28. Wu, CY, Trombly, CA, Lin, K-C, Tickle-Degnen, L. A kinematic study of contextual effects on reaching performance in persons with and without stroke: influences of object availability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:95–101.