Eating and Swallowing

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Name and locate oral structures concerned with eating and swallowing.

2 Name and describe the stages of normal eating and swallowing.

3 List the components of the swallowing assessment.

4 Name and describe normal and abnormal oral reflexes.

5 Describe the role of the occupational therapist in the clinical assessment of eating and swallowing.

6 Describe four steps in the swallowing assessment.

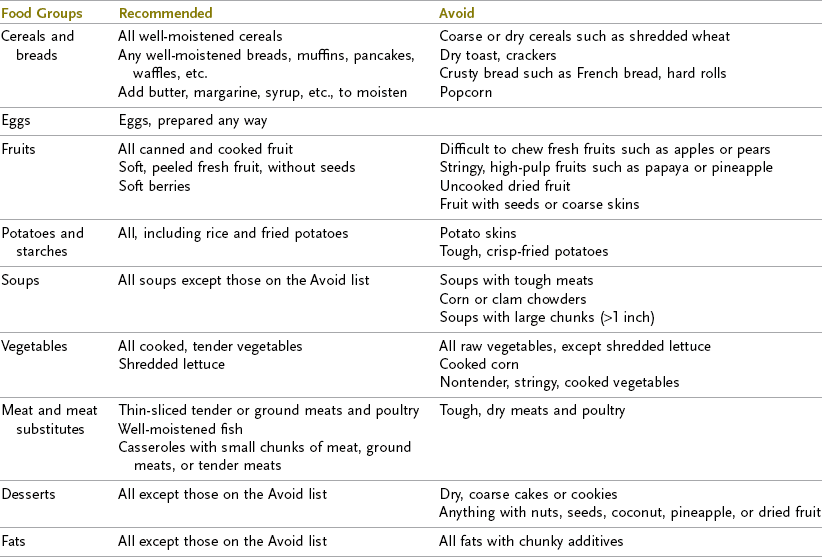

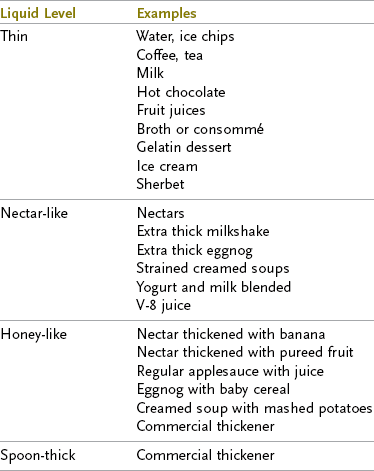

7 Describe the appropriate progression of foods and liquids in the assessment and intervention of deglutition and dysphagia.

8 Name two types of tracheostomy tubes, and list the advantages and disadvantages of each.

9 List symptoms of swallowing dysfunction.

10 Identify basic intervention goals for clients with eating and swallowing dysfunction.

11 Describe the roles of the dysphagia team members.

12 Describe proper positioning for safe feeding and swallowing.

13 Describe two methods of non-oral feeding.

14 List principles of oral feeding.

15 List and describe intervention techniques for management of eating and swallowing dysfunction.

Eating is the most basic activity of daily living, necessary for survival from birth until death. Eating occurs throughout life development in a variety of contexts and in every culture and is an essential activity of daily living that facilitates an individual’s basic survival and well-being.3,8 Although eating and feeding are closely related, these terms are not synonymous. The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, Second Edition (OTPF-2) defines feeding as “the process of setting up, arranging, and bringing food (fluids) from the plate or cup to the mouth; sometimes called self feeding” and eating or deglutition as “the ability to keep and manipulate food/fluid in the mouth and swallow it; eating and swallowing are often used interchangeably” (p. 631).3 Swallowing is a complicated act that involves moving food, fluid, medication, or saliva through the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus into the stomach.5,43 Feeding, eating, and swallowing are influenced by contextual issues, including psychosocial, cultural, and environmental factors.5 Dysphagia is difficulty with swallowing or the inability to swallow.

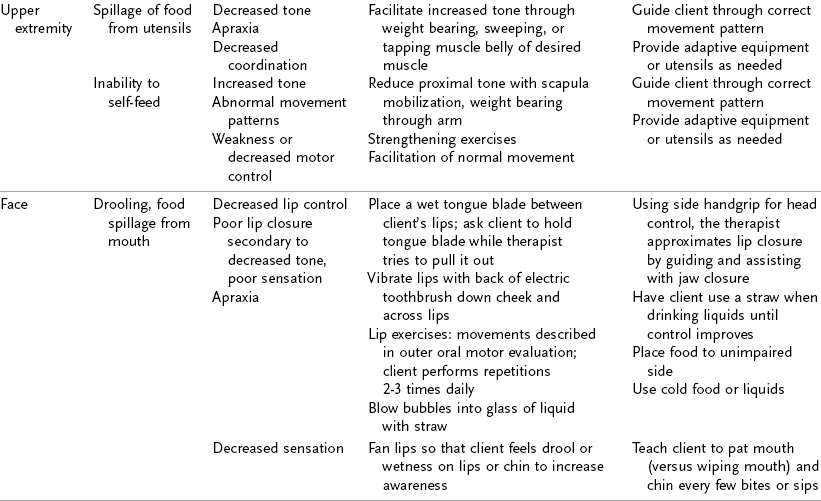

Feeding, eating, and swallowing are within the domain and scope of practice of occupational therapy, and occupational therapists are trained to assess and provide intervention for the performance issues involved in these activities.3,4 Performance skills such as motor and praxis, sensory-perceptual, emotional regulation, and cognitive skills; client factors such as muscle strength, endurance and motor control, muscle tone, normal and abnormal motor reflexes, respiratory system function, and digestive system function; activity demands such as social demands relating to the social environment and cultural contexts, sequence and timing, and required body functions and structures; and performance patterns including the habits, routines, and rituals that may interfere with the eating process are assessed. The contexts and environments, including those that are cultural, personal, and social, that may influence the client’s successful engagement in eating are also assessed.5

This chapter provides the occupational therapist with a foundation for the assessment and intervention process of the adult client with eating and swallowing dysfunction. Conditions that can result in eating and swallowing problems include cerebral vascular accident (CVA), traumatic brain injury, brain tumor, anoxia, Guillain-Barré syndrome, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, myasthenia gravis, poliomyelitis, post-polio syndrome/muscular atrophy, and quadriplegia.22 Anatomic or developmental dysphagia is not included in this chapter.

Anatomy and Physiology of Normal Eating Swallow

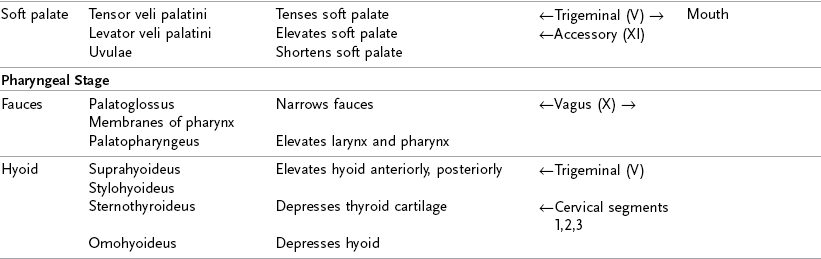

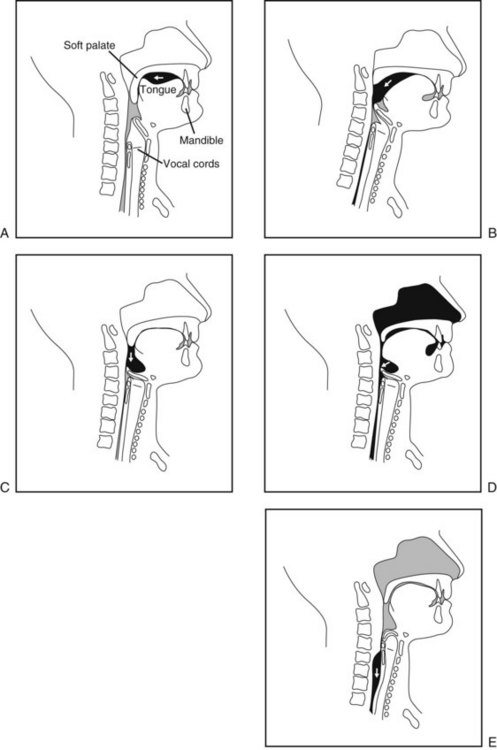

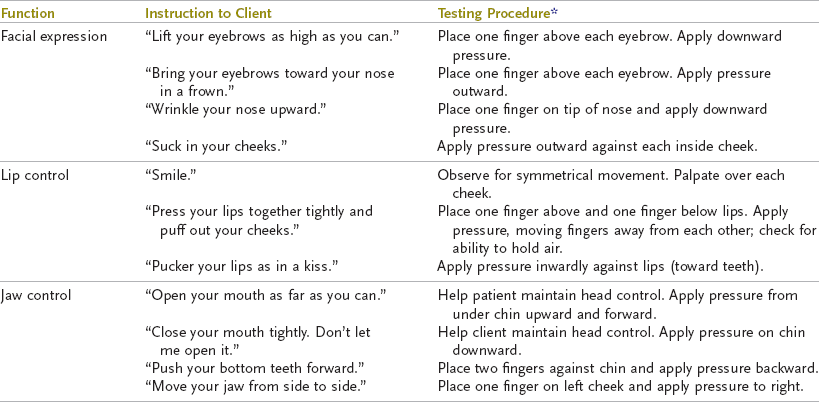

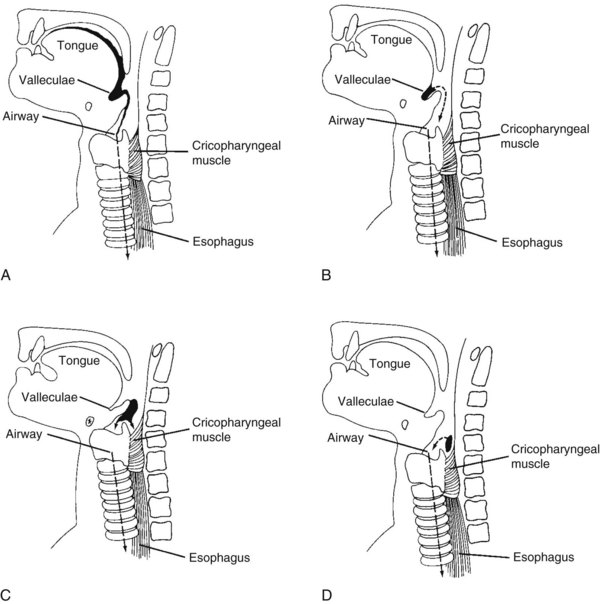

Deglutition, the normal consumption of solids or liquids, is a complex sensorimotor process involving the brain stem, the cerebral cortex, six cranial nerves, the first three cervical nerve segments, and 48 pairs of muscles.28,43 A normal swallow requires that all these structures to be intact (Figure 27-1). Therefore, occupational therapists who work with clients with eating and swallowing problems must have a thorough understanding of the anatomy and physiology of all phases of the swallow (Table 27-1). The eating and swallowing process can be divided into four stages: oral preparatory phase, oral phase, pharyngeal phase, and esophageal phase (Figure 27-2).5,43 An additional phase, the anticipatory phase, will also be discussed.

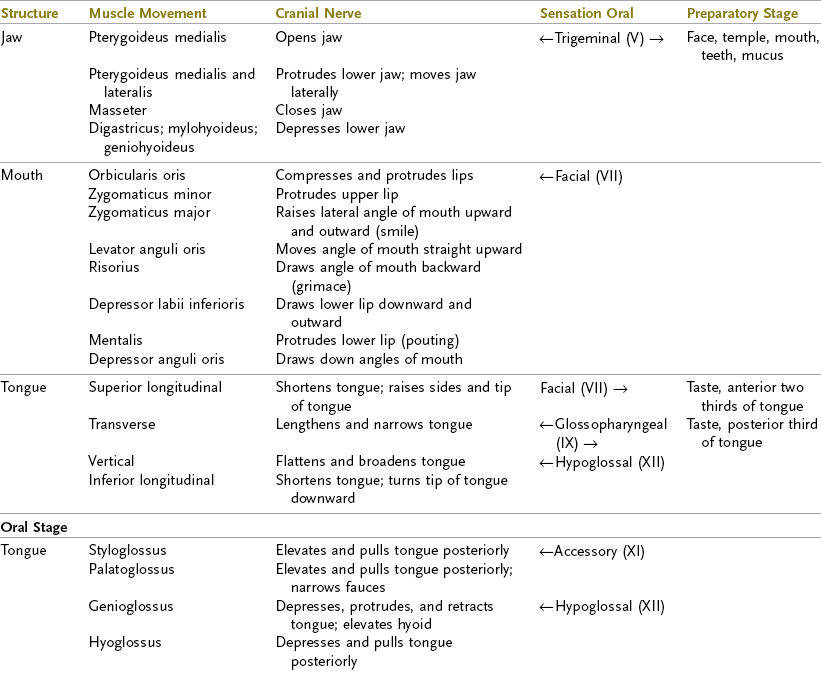

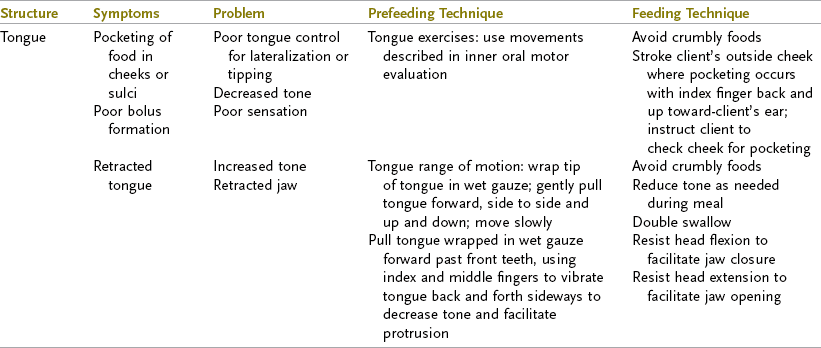

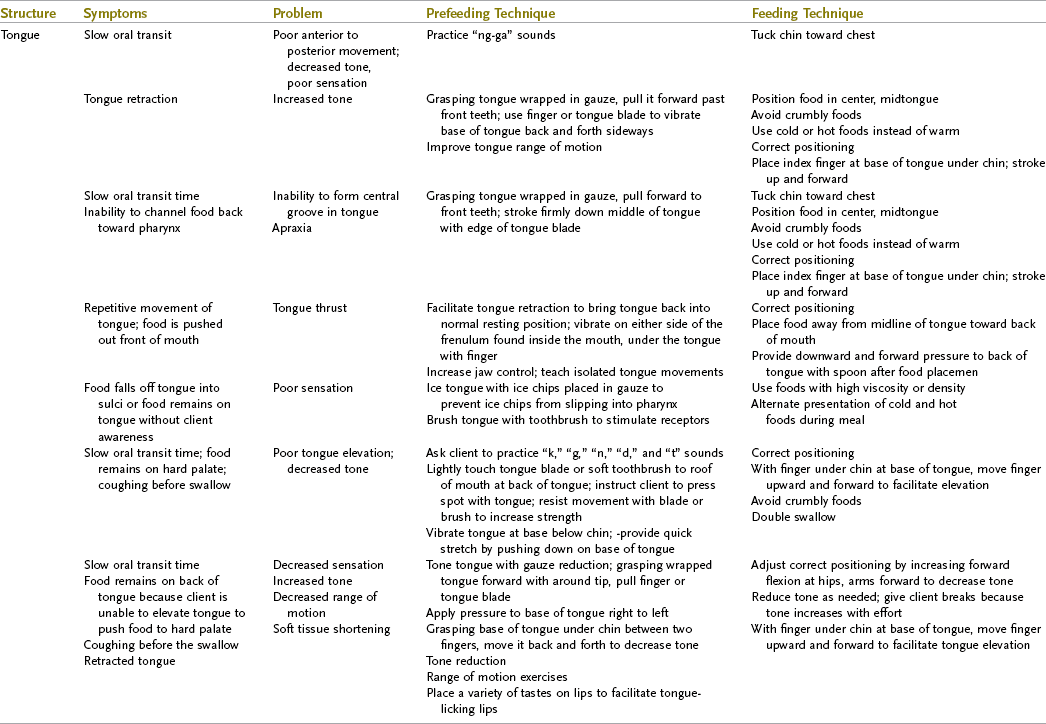

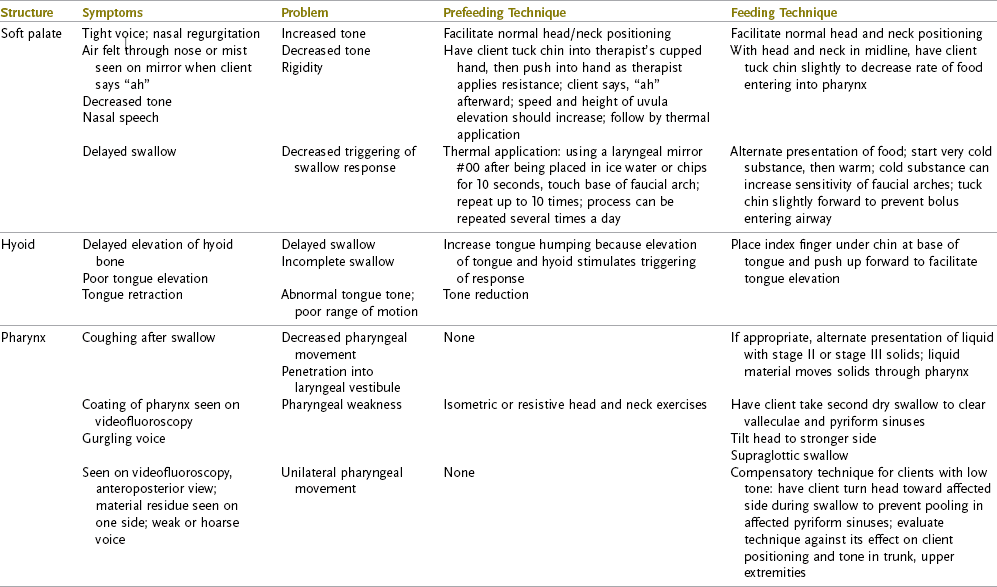

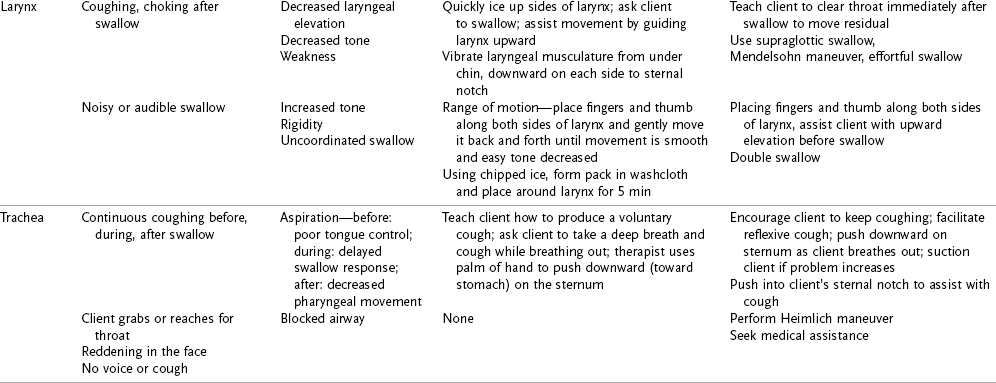

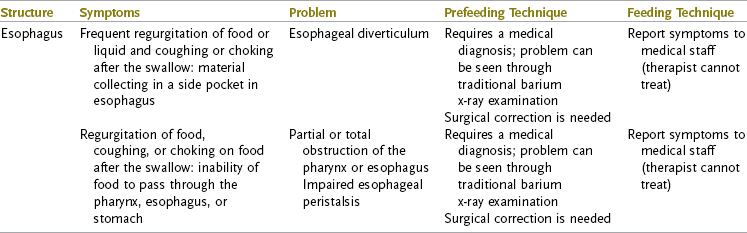

TABLE 27-1

From Bass N: The neurology of swallowing. In Groher M, editor: Dysphagia: diagnosis and management, ed 3, Newton, MA, 1997, Butterworth-Heinemann; Davies P: Steps to follow, New York, 1985, Springer-Verlag; Hislop H, Montgomery J, Connelly B: Daniels & Worthington’s muscle testing: techniques of manual examination, ed 6, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders; Liebman M: Neuroanatomy made easy and understandable, Rockville, MD, 1986, Aspen; Netter F, Dalley A: Atlas of human anatomy, ed 2, 1998, Ciba-Geigy, New Jersey: ←, movement function; →, sensory function.

FIGURE 27-1 Oral structures, swallowing mechanism at rest. (Courtesy Rene Padilla, Occupational Therapy Department, Creighton University, 1994.)

FIGURE 27-2 The normal swallow. A, Lateral view of bolus propulsion during the swallow, beginning with the voluntary initiation of the swallow by the oral tongue. B, Triggering of the pharyngeal swallow. C, Arrival of the bolus in the vallecula. D, Tongue base retraction to the anteriorly moving pharyngeal wall. E, Bolus in the cervical esophagus and the cricopharyngeal region. (From Logemann J: Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders, Austin, TX, 1998, Pro-Ed.)

Anticipatory Phase

Psychological factors, social interactions, a poor dining environment, and cultural differences contribute to feeding difficulties.12 The psychological, emotional, and social aspects surrounding mealtime can have a huge impact on an elderly individual’s participation in the feeding process and oral intake. Factors to be considered that may have an effect on the anticipatory phase include the variety of foods offered, presentation of food, seating during meals, mealtime atmosphere, respect of caregivers for food preferences (Carrier, West, & Ouellet, 2009), and mealtime habits and routines.

The anticipatory phase begins even before the client enters the dining area. The client’s expectations of the eating experience will influence his or her reaction to the dining environment and to the foods presented. Appetite/hunger; the sensory qualities of the food; the sensory qualities of the utensils, cups, and plates; the client’s motivation to eat; and cognitive awareness of the eating activity will all have an impact on the degree to which the client engages in the feeding process. The anticipatory phase is an important precursor to successful eating. The occupational therapist can be instrumental in identifying environmental modifications that can positively influence the client’s response to the eating experience.

Oral Preparatory Phase

In the oral preparatory phase of the swallow, food is masticated by the teeth and gums (if necessary) and manipulated by the lips, cheek, and tongue to form a bolus of appropriate texture for swallowing.5,46 Visual and olfactory information stimulates salivary secretions from three pairs of salivary glands. Saliva is mixed with the food to prepare the bolus for the swallow.29 As tactile contact is made with the food, the jaw comes forward to open. The lips close around the glass or utensil to remove the food or liquid. The labial musculature forms a seal to prevent any material from leaking out of the oral cavity. This phase reflects the close relationship between feeding and eating. As Mattias brought food to his mouth, he did not have symmetrical lip closure on utensils or a glass and often food or fluid would dribble from the left side of his mouth.

As chewing begins, the mandible and tongue move in a strong, combined rotary and lateral direction. The upper and lower teeth shear and crush the food. The tongue moves laterally to push the food between the teeth. The buccinator muscles of the cheeks contract to act as lateral retainers, to prevent food particles from falling into the sulcus between the jaw and cheek.43 The tongue sweeps through the mouth, gathering food particles and mixing them with saliva. Recall that Mattias frequently had food remaining in his cheek after swallowing. This pocketing of food in the cheek may occur from diminished motor control of the tongue to manipulate the bolus or may indicate diminished sensory appreciation for food remaining in the sulcus. Sensory receptors throughout the oral cavity carry information of taste, texture, and temperature of the food or liquid through the seventh and ninth cranial nerves to the brain stem. The chewing action of the mandible and tongue is repeated rhythmically, repositioning the food until a cohesive bolus is formed. The length of time needed to form a bolus one can safely swallow varies with the viscosity of the food. A short time is needed for soft foods, and a longer time is needed for more textured or dense foods.32,53 Large amounts of thick liquids or thick and dense foods require the tongue to divide the food into smaller parts to be swallowed one at a time. The posterior portion of the tongue forms a tight seal with the velum, preventing slippage of the bolus or liquid into the pharynx.43 Foods that are a mixture of liquid and solids (such as soup with chunks of vegetables) require greater oral motor control and often present a difficulty for clients with oral preparatory phase swallowing problems.

In preparation for the next stage, the solid or liquid bolus, having been formed into a cohesive and swallowable mass, may be held between the anterior tongue and palate, with the tongue tip either elevated or dipped toward the floor of the mouth.43 The tongue cups around the bolus to seal it against the hard palate. The larynx and the pharynx are at rest during this phase of the swallowing process, and the airway is open.

Problems at the oral preparatory phase can lead to a disruption in the normal swallow sequence. Mattias has problems with this phase of the eating process. Of additional concern to Mattias is the embarrassment of having food or fluid dribble from the left side of his mouth. His decreased sensory awareness compromises his ability to notice foods/fluids and use a napkin to wipe the remaining food from his face.

Oral Phase

The oral phase of swallowing begins when the tongue initiates posterior movement of the bolus toward the pharynx.37 The tongue elevates to squeeze the bolus up against the hard palate and forms a central groove to funnel the bolus posteriorly. As the viscosity of the food increases, the amount of pressure created by the tongue against the palate increases. Thicker foods require more pressure to propel them efficiently through the oral cavity.43

The oral phase of the swallow is voluntary, requiring the person to be alert and involved in the process. A normal voluntary oral phase is necessary to elicit a strong swallow response during the pharyngeal stage that follows. This stage of the swallow requires intact labial musculature to maintain food or liquid inside of the oral cavity, intact lingual movement to propel the bolus toward the pharynx, intact buccal musculature to prevent material from falling into the lateral sulci, and the ability to comfortably breathe through the nose.19 The oral phase takes approximately 1 second to complete with thin liquids and slightly longer with thick liquids and textured foods.

Mattias is alert but has difficulties maneuvering food within his mouth during the oral phase. His ability to chew textured foods is compromised, and he requires additional time to chew foods. This contributes to the decreased oral intake.

Pharyngeal Phase

Voluntary and involuntary components are necessary for a normal swallow. Neither mechanism alone is sufficient to produce the immediate, consistent swallow necessary for normal eating.43 The pharyngeal phase marks the beginning of the involuntary portion of the swallowing process.

This phase of swallowing begins when the bolus passes any point between the anterior faucial arches and where the tongue base crosses the lower rim of the mandible into the pharynx, marking the start of the involuntary component of the swallow.43,61 After the swallow response has been triggered, it continues with no pause in bolus movement until the total act has been completed. The pharyngeal swallow is controlled by central pattern-generating (CPG) circuitry of the brain stem and peripheral reflexes.37 Within the medulla oblongata the medullary reticular formation is responsible for screening out all extraneous sensory patterns and for responding only to those patterns that indicate the need to swallow. The reticular formation also assumes control of all motor neurons and related muscles needed to complete the swallow. Higher brain functions such as speech and respiration are preempted.48

When the swallow response is triggered, several physiologic functions occur simultaneously. The velum elevates and retracts, closing the velopharyngeal port to prevent regurgitation of material into the nasal cavity. The tongue base elevates to direct the bolus into the pharynx. The hyoid and the larynx elevate and move anteriorly. There is closure of the larynx at the vocal folds, the laryngeal entrance and the epiglottis to prevent material from entering the airway. The pharyngeal tube elevates and contracts from the top to the bottom in the pharyngeal constrictors using a squeezing motion to move the bolus through the pharynx toward the esophagus. The bolus passes through the pharynx, dividing in half at the valleculae and moving down each side through the pyriform sinuses toward the esophagus. The upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxes and opens, allowing the material to enter the esophagus.29,43 This movement must be rapid and efficient so that respiration is interrupted only briefly. The pharyngeal phase of the swallow takes approximately 1 second to complete for thin liquids.

Mattias frequently coughs, indicating difficulties with the timing and coordination of the pharyngeal phase. His problems swallowing water may indicate diminished laryngeal elevation and decreased airway protection during the swallow.

Esophageal Phase

The esophageal phase of the swallow starts when the bolus enters the esophagus through the cricopharyngeal juncture or upper esophageal sphincter (UES). The esophagus is a straight tube, approximately 10 inches long, that connects the pharynx to the stomach. The pharynx is separated from the esophagus by the UES. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) separates the esophagus from the stomach. During the swallow, the strong muscles of the esophagus contract and the bolus is transported through the esophagus by peristaltic wave contractions. The overall transit time needed for the bolus to reach the stomach varies from 8 to 20 seconds. As the food enters the esophagus, the epiglottis returns to the relaxed position, and the airway opens.29,43

Mattias complains of frequently coughing and choking on food and fluid. This may be due to problems with the preoral, oral, pharyngeal, or esophageal phase of eating. As you read the following section, use the case presentation of Mattias and consider what assessment results you would look for to identify which phase is producing the episodes of coughing and choking.

Eating and Swallowing Assessment

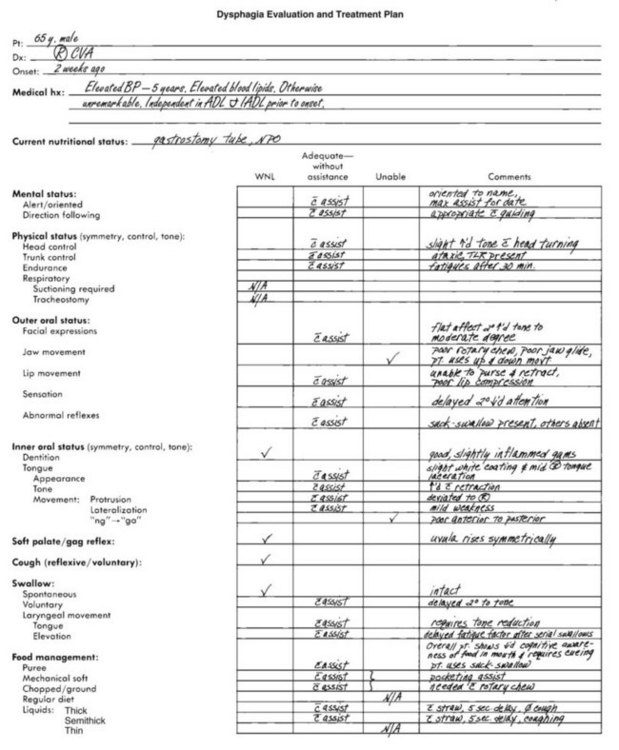

When a referral is received from a physician, a thorough eating and swallowing assessment for possible dysfunction must be completed. The occupational therapist reviews the client’s medical history and assesses the client’s perceptual, and cognitive skills; physical control of head, trunk, and extremities; oral structures; sensation and swallowing ability.

Medical Chart Review

A review of the client’s medical chart before initiating the bedside assessment reveals important information. The therapist should take note of the client’s diagnosis, pertinent medical history (including prior incidents of aspiration), prescribed medications, and current hydration and nutritional status.

The medical diagnosis may indicate the etiology or cause of the client’s eating or swallowing problems. For example, a diagnosis of a neurologic disorder such as a CVA should alert the therapist that eating or swallowing problems may exist.22 It is important to know whether problems developed suddenly or gradually. The therapist should seek information regarding the duration of the client’s swallowing difficulties and note any secondary diagnoses that could contribute to dysphagia such as gastrointestinal or respiratory problems or changes in medication. A diagnosis of dehydration, weight loss, or malnutrition may indicate a chronic problem with deglutition.

Particular attention should be paid to reported episodes of pneumonia or aspiration (entry of food or material into the airway below the level of the true vocal folds).28 Aspiration pneumonia occurs when food or material enters into the lung and can be a serious medical complication that is identified by x-ray and treated with antibiotics. Possible predictors of pneumonia include the need for frequent suctioning, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), use of a feeding tube, weight loss, swallowing problems, multiple medications, and eating dependence.38 An elevated temperature may also indicate that a client is aspirating.

An examination of the client’s current hydration and nutritional status provides valuable information about the client’s ability to manage oral intake. This information can be found in the dietary section of the chart or in the nursing progress notes in the intake and output (I & O) record. An altered diet texture (pureed food or thickened liquids) alerts the therapist to a potential problem with the client’s ability to safely eat a regular diet. The presence of an intravenous (IV) fluid may indicate dehydration. Weight loss is frequently a result of a swallowing problem. Consideration should be given to prescribed medications that may alter the client’s alertness, orientation, saliva production, appetite, and muscle control. The nursing notes may also indicate whether the client coughs or chokes when taking medications. How the client is receiving nutrition is also important—for example, the presence of a non-oral feeding device such as a nasogastric tube (NG tube) or gastrostomy tube (G tube) is often an indication of a serious dysphagia problem.

Occupational Profile

In the beginning of the evaluation process, the therapist obtains information from the client to develop the occupational profile. Information gathered for the profile is designed to help the therapist understand what is meaningful and important to the client.3 Prior eating habits and routines and the importance of eating to the client (and the client’s family or significant other) are essential to know so that interventions can be established to meet the client’s needs. The occupational therapist must take into consideration the cultural values, beliefs, habits, and routines of the client revolving around food and eating. The client may have strong feelings about particular foods, food temperatures, or food textures. Food and food preparation methods may be symbolically meaningful to clients and may have a strong impact on the client’s oral intake. The presentation of food may have a significant influence on the individual’s desire to participate in eating. Most adults have firmly rooted routines surrounding the activity of eating. For example, an elderly person may eat a late breakfast, a larger meal at midday, and only a light meal in the evening. He or she may watch TV while eating. This routine can be severely interrupted in an institutionalized setting.

The intervention program is developed based on information provided to the therapist in the occupational profile. Mattias clearly identified his intervention priorities and discussed his concerns about participating in his daughter’s wedding. The issues related to eating and drinking are closely tied to the cultural and social expectations for the father of the bride.

Cognitive-Perceptual Status

The client’s cognitive and perceptual abilities are assessed to determine if the client can actively participate in an eating and swallowing assessment and intervention program. The therapist should establish whether the client is alert, oriented, and able to follow simple directions, either verbal, with demonstration, or with manual guidance. It is important to assess the client’s memory to determine if he or she will be able to recall strategies for safe eating. The therapist should also evaluate the client’s visual function, visual-perceptual skills, and motor planning skills, as they are important for independent feeding. An individual who exhibits confusion, dementia, poor awareness of the eating task, poor attention span, or impaired perception or memory will require close supervision during eating for safe consumption.10,12,49

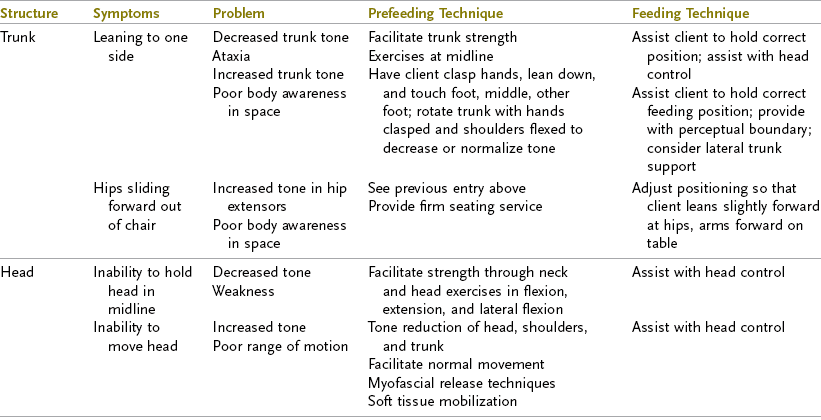

Physical Status

Control of head and trunk is an important component of a safe swallow. To assess head control, the therapist asks the client to turn the head from side to side and up and down. The therapist assesses the client’s range of motion and motor control. Assessment should include the quality of head movement without physical assistance or support initially and with assistance, if needed. The therapist should also gently move the client’s head passively from side to side and up and down to look for stiffness or abnormal muscle tone. Poor head control may indicate decreased strength, decreased or increased muscle tone, or decreased awareness of posture. Appropriate head control is necessary to provide a stable base for adequate jaw and tongue movement, allowing an optimal swallow response. Head control is also necessary to anatomically position the client in the safest posture to reduce the risk of aspiration.

In assessing the client’s trunk control, the therapist observes whether the client is sitting in midline with equal weight bearing on both hips. The therapist assesses the client’s ability to maintain the midline position independently when involved in eating or whether he or she requires the use of postural supports (such as wheelchair trunk supports or a lap board) or physical assistance. It is also important to determine if the client can return to midline if a loss of balance occurs. To participate in an eating and swallowing intervention program, the client must maintain an upright position with the head and trunk in midline to provide correct alignment of the swallowing structures and reduce the risk of aspiration caused by poor positioning.

Mattias is able to independently sit in a chair and at the side of the bed. His head control appears adequate, but he tends to sit shifted to his right side, and his head is most often facing to the right side instead of positioned in midline. This indicates poor trunk and head alignment and can impact eating.

Oral Assessment

The face and mouth are sensitive areas to assess. Most adults are cautious about or even threatened by having another person touch their face. Therefore, each step of the assessment process should be carefully explained prior to touching the client, using terms that the individual understands. The therapist also should tell the client how long he or she will be touching the face—for example, “For a count of three.” The therapist assesses the outer oral structures, including the facial musculature and mobility of the cheeks, jaw, and lips. Working within the client’s visual field, the therapist moves his or her hand(s) slowly toward the client’s face. This allows the individual time to process and acknowledge the approach.

Sensation: Indications of poor oral sensation include drooling, food remaining on the lips, and food falling out of the mouth without the client being aware of these events. To assess the client’s awareness of touch, the therapist occludes the client’s vision and uses a cotton-tipped swab to touch the client gently with a quick stroke to different areas of the face. The individual is asked to point to where he or she was touched. If pointing is difficult, the client is asked to nod or say yes or no when touched. The client with intact sensation responds accurately and quickly.

The client’s ability to sense hot and cold should be assessed. The therapist may use two test tubes, one filled with hot water and one with cold water. A laryngeal mirror that is first heated and then cooled using hot and cold water may also be used. The client’s face or lips are touched in several places, and the client is asked to indicate whether the touch was hot or cold. An aphasic client or an client with cognitive impairment may have difficulty responding accurately. In this instance, the therapist must make an assessment from clinical observations.

Poor sensory awareness affects the client’s ability to move facial musculature appropriately. The client’s self-esteem may be affected, especially in social situations, if decreased awareness causes the client to ignore saliva, food, or liquids remaining on the face or lips.

Consider Mattias and his personal goal of eating at his daughter’s wedding rehearsal dinner. The diminished sensation around Mattias’ face will need to be addressed to avoid his embarrassment during this important event. Strategies that promote compensatory habit formation should be used, such as having Mattias wipe his face after every second or third bite of food to remove any food on his face. This strategy provides additional sensory input to the face in addition to decreasing the potential embarrassment of having food remain on his face.

Musculature: An assessment of the facial muscles provides the therapist with information about the movement, strength, and tone available to the client for chewing and swallowing. The therapist first observes the client’s face at rest and notes any visible asymmetry. If a facial droop is obvious, the therapist should observe whether the muscles feel slack or taut. A masked appearance, with little change in facial expression, may also be observed. The therapist should observe whether the client appears to be frowning or grimacing with the jaw clenched and the mouth pulled back. This facial posture may indicate increased or decreased muscle tone.

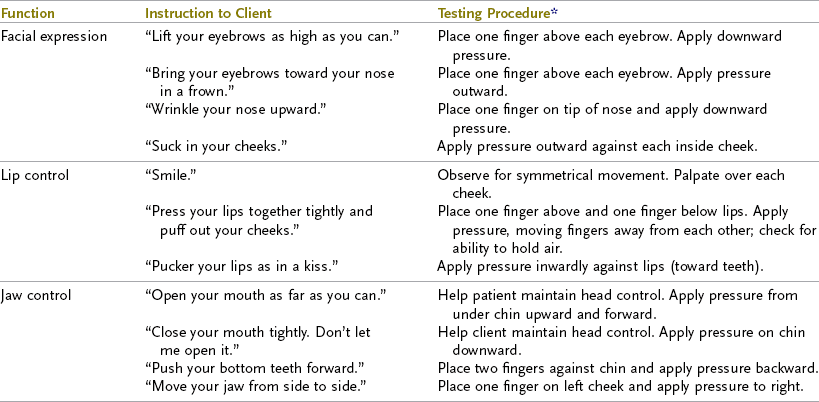

The therapist tests the facial musculature by asking the client to perform the movements listed in Table 27-2. The therapist should note how much assistance the client needs to perform these movements. As the client moves through each task, symmetry of movement is assessed. Asymmetry could indicate weakness or increased tone. Musculature is palpated for abnormal resistance to the movement.

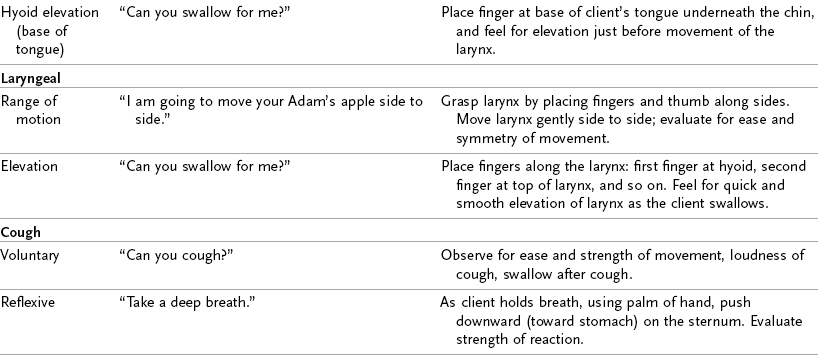

TABLE 27-2

*Apply resistance only in the absence of abnormal muscle tone.

Data from Alta Bates Hospital Rehabilitation Services: Bedside dysphagia evaluation protocol, Berkeley, CA, 1999; Community Hospital of Los Gatos, Rehabilitation Services: Dysphagia protocol, Los Gatos, CA, 1999; Logemann J: Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders, Austin, TX, 1998, Pro-Ed; Miller R: Clinical examination for dysphagia. In Groher M: Dysphagia diagnosis and management, ed 3, Newton, MA, 1997, Butterworth-Heinemann.

If the client is able to hold the position at the end of the movement, the therapist applies gentle pressure against the muscle to determine strength. An individual with normal strength is able to hold the position throughout the applied resistance. The person who is able to hold the position briefly against pressure may have adequate strength for chewing and swallowing but may require an altered diet.

Oral Reflexes: A client who has sustained damage to brain stem or cortical structures may demonstrate primitive oral reflexes that interfere with a dysphagia-retraining program. The presence of the rooting, bite, or suck-swallow reflex, normal from 0 to 5 months of age, will interfere with oral motor control in adults. Persistence of these primitive oral reflexes interferes with the client’s isolated oral motor control, which is needed for chewing and swallowing. The gag, palatal, and cough reflexes should be present in adults and contribute to airway protection. The absence or impairment of these important reflexes may interfere with a safe swallow. Specific assessment techniques are presented in Table 27-3.

TABLE 27-3

Data from Avery-Smith W: Management of neurologic disorders: the first feeding session. In Groher M, editor: Dysphagia: diagnosis and management, ed 3, Newton, MA, 1997, Butterworth-Heinemann; Farber S: Neurorehabilitation: a multisensory approach, Philadelphia, 1982, WB Saunders; Logemann J: Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders, Austin, TX, 1998, Pro-Ed; Schulze-Delrieu K, Miller R: Clinical assessment of dysphagia. In Perlman A, Schulze-Delrieu K, editors: Deglutition and its disorders: anatomy, physiology, clinical diagnosis and management, San Diego, CA, 1997, Singular.

Intraoral Status

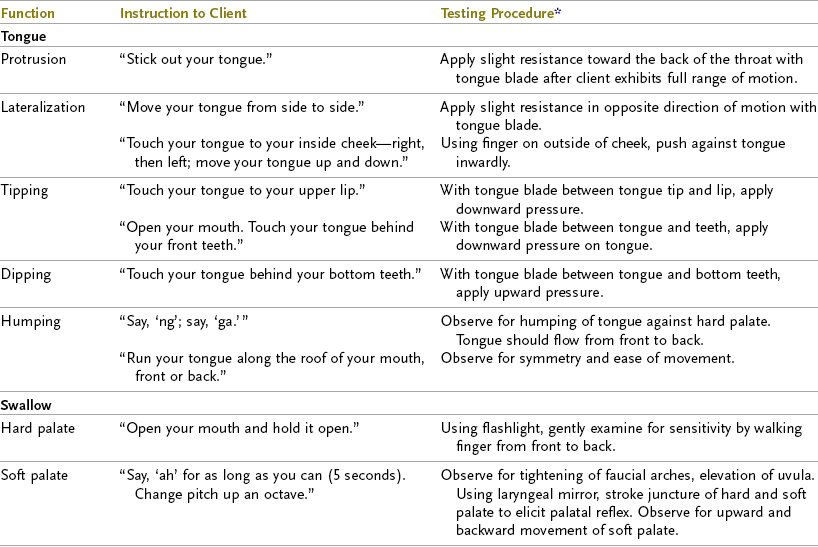

An assessment of the client’s intraoral status includes an examination of oral structures, including the tongue and palatal function. Each procedure is first explained to the client. The therapist works within the client’s visual field and gives the person time to process the instructions found in Table 27-4.

TABLE 27-4

*Apply resistance in absence of abnormal muscle tone.

Data from Community Hospital of Los Gatos, Rehabilitation Services: Dysphagia protocol, Los Gatos, CA, 1999; Coombes K: Swallowing dysfunction in hemiplegia and head injury, course presented by International Clinical Educators, Aug 24-27, 1986, and Aug 24-28, 1987, Los Gatos, CA; Hislop H, Montgomery J, Connelly B: Daniels & Worthington’s muscle testing: techniques of manual examination, ed 6, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders; Miller R: Clinical examination for dysphagia. In Groher M: Dysphagia diagnosis and management, ed 3, Newton, MA, 1997, Butterworth-Heinemann; Schulze-Delrieu K, Miller R: Clinical assessment of dysphagia. In Perlman A, Schulze-Delrieu K, editors: Deglutition and its disorders: anatomy, physiology, clinical diagnosis and management, San Diego, CA, 1997, Singular.

Standard precaution techniques are used throughout the assessment and include the use of examination gloves and careful hand washing. The therapist should check for allergies to latex before examining the person’s mouth and use an examination glove of appropriate material for an intraoral examination. The therapist must place only a wet, gloved finger or dampened tongue blade into the client’s mouth. The mouth is normally a wet environment and a dry finger or tongue blade can be uncomfortable. After a count of three, the therapist removes the finger and allows the client to swallow the secretions that may have accumulated.

Dentition: Because the adult uses teeth to shear and grind food during bolus formation, it is important for the therapist to assess the condition and quality of the client’s teeth and gums. Poor dental status or inadequate denture fit can contribute to dysphagia, discomfort or pain with swallowing, dehydration, malnutrition, low dietary intake, poor nutritional status, and weight loss.49,54,55

For assessment purposes, the mouth is divided into four quadrants: right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower. Each quadrant is assessed separately, as is each side (e.g., assess the right upper side, then the right lower side). First the therapist slides a wet fifth finger under the client’s upper lip and moves it back toward the cheek, rubbing the gums three times.16 The therapist notes whether the client’s gums are bleeding, tender, or inflamed and whether the gums feel spongy or firm. Loose teeth and sensitive or missing teeth are also noted.

After assessing the gums, the therapist turns over his or her finger, slides the pad of the finger against the inside of the client’s cheek, and gently pushes the cheek outward to feel the tone of the buccal musculature. The therapist notes whether the cheek is firm with an elastic quality, too easy to stretch, or tight without any stretch. The therapist observes the condition of the inside of the client’s mouth, checking for bite marks on the tongue, cheeks, and lips. Next, the therapist should remove the finger from the client’s mouth, allow or assist the client to swallow saliva, and assist the client to move the lip and cheek musculature into the normal resting position. This procedure is repeated for each quadrant.

If the client has dentures, the therapist must determine whether the fit is adequate for chewing. Because dentures are held in place and controlled by normal musculature and sensation, changes in these areas, or marked weight loss, affect the client’s ability to use dentures effectively for eating. Dentures should fit over the gums without slipping or sliding during eating or talking. Well-fitting dentures should be worn during all oral intake. A dental consultation may be needed to ensure appropriate fit if dentures cannot be held firmly with commercial adhesive creams or powders. Loose dentures or teeth may necessitate changes in food consistencies that the client may have otherwise managed. Clients who have gum or dental problems require appropriate follow-up and excellent oral hygiene to participate in a feeding and eating program. Poor oral hygiene can lead to the development of bacteria, which, if aspirated, contributes to the increased risk of pneumonia.6,21,27,47,57

Tongue Movement: The tongue has a critical role in the normal chewing and swallowing process. Controlled lingual movement is necessary to assist in the preparation and movement of food in the mouth.19 The extrinsic muscles of the tongue control the position of the tongue in the oral cavity, and the intrinsic muscles are responsible for changing the shape of the tongue, which is necessary in propelling the bolus posteriorly.60 Lingual discoordination is one of the most commonly reported problems affecting the oral stage of swallowing.66 A thorough assessment of the tongue’s strength, range of motion, control, and tone is an important component of the swallowing assessment.

The client is asked to open the mouth, and the therapist assesses the appearance of the tongue using a flashlight and notes whether the tongue is pink and moist, red, or heavily coated and white. A heavily coated tongue decreases the client’s sensations of taste, temperature, and texture and may indicate poor tongue movement or may be a sign of infection.

When examining the shape of the tongue, the therapist notes whether it is flattened, bunched, or rounded. Normally, the tongue is slightly concave with a groove running down the middle. The therapist observes the tongue at rest in the mouth and determines whether it is in the normal position of midline, resting just behind the front teeth, retracted or pulled back away from the front teeth, or deviated to the right or left side. A retracted tongue may indicate an increase of abnormal muscle tone or a loss of range of motion as a result of soft-tissue shortening. The client exhibiting tongue deviation with protrusion may have muscle weakness on the affected side, causing the tongue to deviate toward the unaffected side because the stronger muscles dominate. The client also may have abnormal tone, which results in the tongue deviating toward the affected side.

Using a wet gauze pad to grasp the tongue gently between the forefinger and thumb, the therapist pulls the tongue slowly forward. Next, the therapist walks a wet finger along the tongue from front to back to determine whether the tongue feels hard, firm, or mushy. The tongue should feel firm. An abnormally hard tongue may be the result of increased muscle tone, and a “mushy” tongue is associated with low muscle tone. The right side of the tongue is compared with the left side for symmetry.

While continuing to grip the tongue between forefinger and thumb, the therapist assesses the client’s range of motion by moving the tongue forward, side to side, and up and down. The tongue with normal range will move freely in all directions without resistance. Moving the tongue through its range, the therapist can simultaneously evaluate tone. As the therapist gently pulls the tongue forward, he or she determines whether it is easily moved or whether resistance is noted. A tongue pulling back against the movement indicates increased tone. A tongue that seems to stretch too far beyond the front teeth indicates decreased tone. When moving the tongue side to side, the therapist notes whether it is easier to move in one direction or the other direction. Increased tone makes it difficult for the therapist to move the tongue in any direction without feeling resistance against the movement. Clients who are confused or apraxic may resist this passive motion but not have an actual increase in tone.

To assess the tongue’s motor control (strength and coordination), the therapist asks the client to elevate, stick out, and move the tongue laterally (see Table 27-4). If the client has difficulty understanding verbal directions, the therapist can use a wet tongue blade to guide the client through the desired movements.

Poor muscle strength or abnormal tone decreases the ability of the tongue to sweep the mouth and gather food particles to form a cohesive bolus. If the tongue loses even partial control of the bolus, food may fall into the valleculae, the pyriform sinuses, or the airway, possibly leading to aspiration before the actual swallow.43 The back of the tongue must also elevate quickly and strongly to propel the bolus past the faucial arch into the pharynx to trigger the swallow response.28 The therapist must carefully assess the tongue’s function. The client with poor tongue control may not be a candidate for eating or may need altered food textures. The therapist must first normalize tone and improve tongue movement before attempting to introduce food to the client. The correct selection of appropriate food textures also facilitates motor control when the client is ready for eating. Close supervision by an experienced therapist is required for this type of client to participate in eating.

Mattias had decreased tongue mobility and control. When he protruded his tongue, it was deviated toward the left, which indicates diminished motor control on the left side of his tongue. An additional indication of diminished tongue control is the pocketing of food in his mouth following a swallow.

Clinical Assessment of Swallowing

Because aspiration is a primary concern in swallowing, the occupational therapist must carefully assess the client’s ability to swallow safely. Before the therapist presents the client with material to swallow, he or she should assess the client’s ability to protect the airway. The client must have an intact palatal reflex, elevation of the larynx, and a productive cough. The purpose of a productive cough is to remove any food or liquid from the airway.29,43 Directions for assessing all the components of the swallow are described in Table 27-4. The therapist should note the speed and strength of each component. The client with intact cognitive skills may accurately report to the therapist where and when difficulty occurs with the swallow.

The occupational therapist integrates all the information from the assessment process. Clinical judgment plays an important role in the accurate assessment of dysphagia.5,13 The following questions should be asked:

1. Is the client alert and able to participate in a swallowing assessment?

2. Does the client maintain adequate trunk and head control, with or without assistance?

3. Does the client display adequate tongue control to form a cohesive bolus and move the bolus through the oral cavity?

4. Is the larynx mobile enough to elevate quickly and with sufficient force during the swallow?

5. Can the client handle the saliva with minimal drooling?

6. Does the client have a productive cough, strong enough to expel any material that may enter the airway?

If the answer is yes to all of these questions, the therapist may assess the client’s oral and swallow control with a variety of food consistencies.

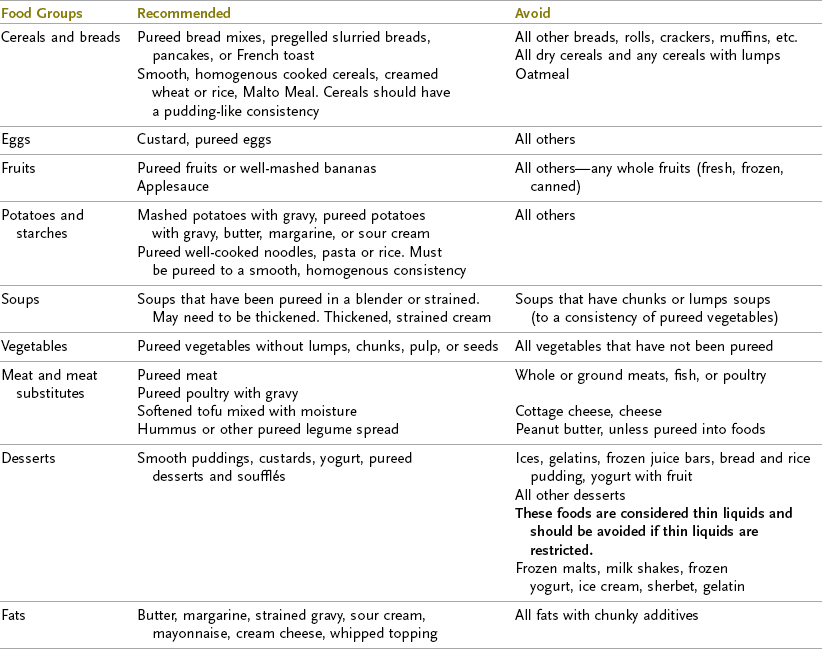

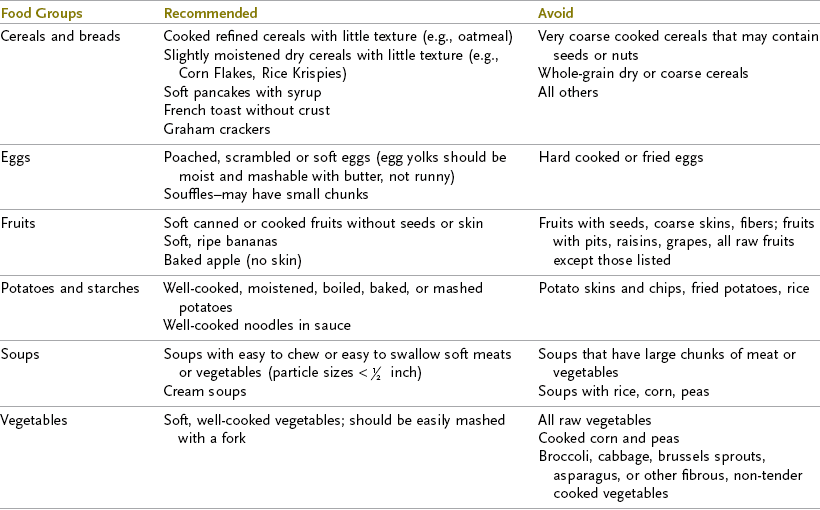

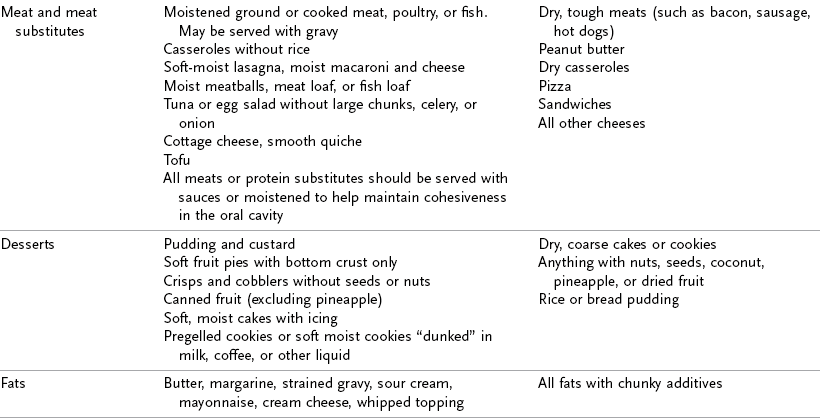

The therapist should request an assessment tray from dietary services. The following foods are merely suggestions and the therapist must consider cultural factors and medical conditions that influence the selection of foods. For example, a vegetarian or a person who is lactose intolerant will require an appropriate selection of foods. The tray should contain a sample of foods of various textures including pureed food such as pudding or applesauce, soft foods such as a banana or macaroni and cheese, and a mechanical soft-textured food such as ground tuna with mayonnaise or chopped meat with gravy. The tray should also include a thick drink such as nectar blended with half of a banana for a 7-ounce drink, a semithick drink such as fruit nectar or a yogurt drink, and a thin, flavored liquid such as juice and water.

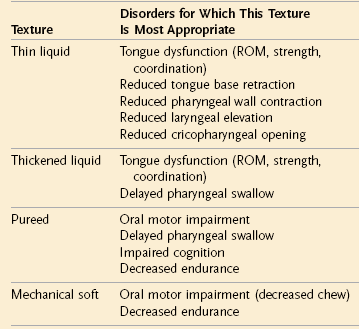

To minimize the risk of aspiration, pureed foods are chosen for clients with decreased oral motor control and chewing difficulties or apraxia. Clients who have poor endurance or have difficulty attending to the task of eating may also require pureed foods. Soft foods are more easily formed into a bolus and require less chewing than regular or ground textures for clients who have impaired oral motor control. Soft foods are also easier for the client to keep in a cohesive bolus as they are moved through the oral cavity. Ground foods allow the therapist to assess a client’s ability to chew, form a cohesive bolus, and move it in the mouth. Thick liquids move more slowly from the front of the mouth to back, giving the client with a delayed swallow or impaired oral motor skills more time to control the liquid until the swallow response is triggered. Thin liquids are the most difficult to control because they require intact oral motor strength and coordination, and an intact swallow to prevent aspiration.

For the client who appears to have some ability to chew, the therapist should start with pureed and soft textures. Solid textures may be introduced next if the client is able to safely and efficiently swallow the pureed and soft food textures. The following procedures should be completed after each swallow of food or liquid:

1. The therapist places a small amount ( teaspoon) of food or liquid on the middle of the client’s tongue. The client is asked to swallow. Two to three bites are presented of each texture to check for fatigue in controlling that texture.

teaspoon) of food or liquid on the middle of the client’s tongue. The client is asked to swallow. Two to three bites are presented of each texture to check for fatigue in controlling that texture.

2. The therapist palpates for the swallow by placing the index finger at the hyoid notch, the second finger at the top of the larynx, and the third finger along the midlarynx. The therapist can feel the strength and smoothness of the swallow and can note whether the client requires subsequent or additional swallows to clear the bolus.43 The therapist evaluates oral transit time by noting when food entered the mouth, when tongue movement was initiated, and when the elevation of the hyoid notch was felt, which indicates the beginning of the swallow process. The therapist can time the swallow from the time that hyoid movement begins to when laryngeal elevation occurs, indicating triggering of the swallow response.43 A normal swallow takes only 1 second to complete for thin liquids and slightly longer for textured foods.

3. The therapist asks the client to open the mouth to check for remaining food. Food is commonly seen in the lateral sulci, under the tongue, on the base of the tongue, and against the hard palate.43 Food remaining in the mouth indicates decreased or impaired oral transit skills. The client who exhibits oral motor deficits has increasing difficulty with chewing, shaping a bolus, and moving the bolus in the oral cavity as textured foods are introduced.

4. The therapist asks the client to say “ah.” By listening carefully, the therapist can assess the client’s voice quality and classify the sound production as strong, clear, gurgly, or gargling.43

A gurgly voice may result from a delayed swallow response, which allows material to collect in the larynx prior to the initiation of the swallow. The therapist asks the client to take a second “dry” swallow to clear any pooling of material. Asking the client to say “ah” again enables the therapist to assess whether the voice quality remains gurgly or gargling for any length of time after the dry swallow. In addition, the therapist asks the client to pant for a few seconds. This will shake loose any material that may remain in the pyriform sinuses or valleculae. If the voice is still gurgly, the therapist should be concerned with the possibility that material has come into contact with or is sitting on the vocal cords.43

If the client has significant coughing episodes, particularly before the therapist feels the initiation of the swallow (elevation of hyoid notch) with all consistencies, the presentation of food should not be continued. Strategies and techniques to facilitate a safe swallow are appropriate to introduce at this point. If the client continues to have significant coughing or other signs that may suggest aspiration, a videofluoroscopy swallow study is indicated.35,50

Although Mattias had frequent episodes of coughing during the bedside evaluation, no gurgly or raspy vocal quality was noted during speech. He is able to clear material from his vocal folds with a strong protective cough. He is able to swallow his secretions, but drooling was noted from the left corner of his mouth, which indicates diminished sensation.

A client with central nervous system damage and impaired sensation may have difficulty with a pureed food because it does not stay together as a bolus. The weight of soft foods, denser than a pureed food, may facilitate the triggering of the swallow response. If the client continues to cough even with soft foods, the swallow assessment should be discontinued. In this instance, a videofluoroscopy swallow study is indicated. If a client is having difficulty at this level, only a prefeeding intervention program should be considered.

Because Mattias is able to safely manage a modified diet texture using positioning strategies and does not have signs and symptoms of aspiration, a videofluoroscopy was not deemed necessary.

A client who has difficulty managing solid consistencies may or may not have difficulty with liquids. To assess the client’s swallow with liquids, the therapist starts with a thickened (thick) nectar, then a pure nectar (semithick), and finally a thin liquid such as water or juice (see Table 27-8, presented later in the chapter). Small amounts of the liquid are placed on the middle of the client’s tongue with a spoon. The therapist proceeds by following the four-step sequence described earlier for solid foods. The therapist assesses the client’s skill at moving material from front to back, the time of oral transit and swallow, and the voice quality after each swallow. Each liquid consistency is assessed for two or three swallows to check for fatigability. If the client tolerates and swallows liquids by spoon without difficulty, the therapist assesses the client’s ability to tolerate liquids from a cup or with a straw. The client’s voice quality is checked following each swallow.

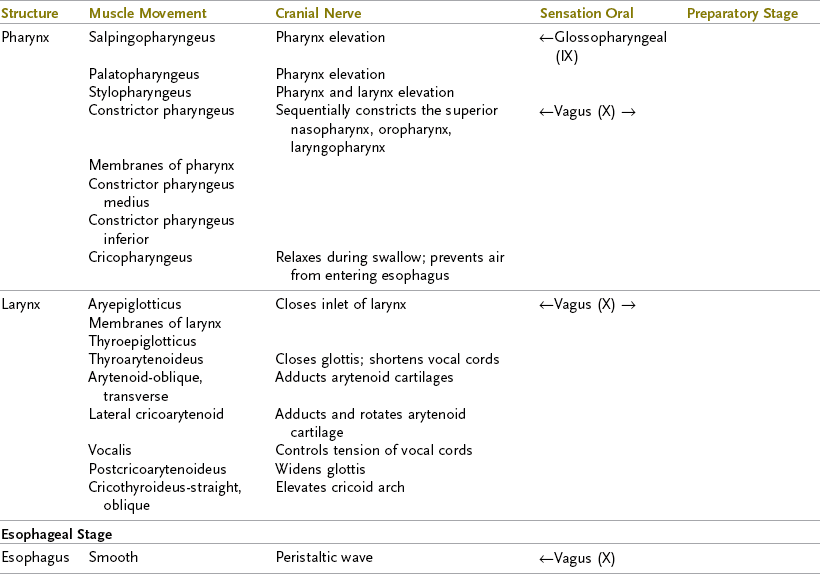

A client with a poor swallow may aspirate immediately or may pool liquids in the pyriform sinuses and valleculae, which, when full, overflow into the laryngeal vestibule and down into the trachea. If a client continues to have a gurgling or gargling voice after a second dry swallow or has substantial coughing with any of the liquid consistencies, the assessment should be discontinued (Figure 27-3).

FIGURE 27-3 Types of aspiration. A, Aspiration before swallow caused by reduced tongue control. B, Aspiration before swallow caused by absent swallow response. C, Aspiration during swallow caused by reduced laryngeal closure. D, Aspiration after swallow caused by pooled material in pyriform sinuses overflowing into airway. (From Logemann J: Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders, San Diego, 1983, College-Hill Press.)

The therapist must also assess the client’s ability to alternate between liquids and solids, which occurs naturally during meals. The therapist presents the client with an easily managed food bolus, followed by the safest type of liquid tolerated, and then assesses the client for coughing when the consistency of the food is changed.

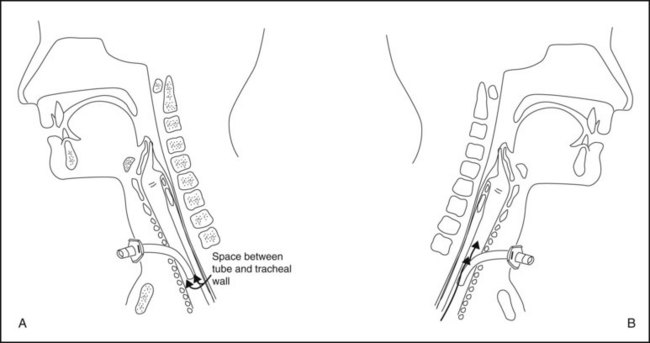

A client with a tracheostomy tube in place can be assessed as previously described. The same criteria must be met before the therapist assesses the client’s eating and swallowing of food or liquids. The therapist must have a thorough understanding of the types of tracheostomy tubes and varied functions. The therapist must also be aware that clients who have had a tracheostomy tube, especially those on ventilation for any length of time, may experience changes in the swallowing mechanism such as muscle atrophy, decreased sensation, and laryngeal damage.15

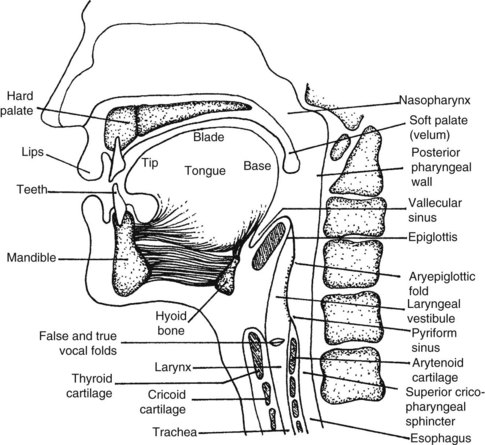

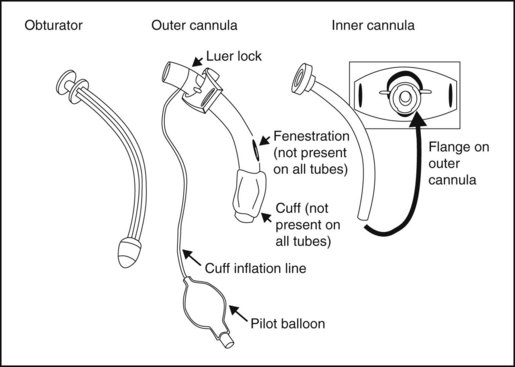

Two main types of tracheostomy tubes exist: fenestrated and nonfenestrated (Figures 27-4 and 27-5).43 A fenestrated tube is designed with an opening in the middle to allow increased air flow. This type of tube is frequently used for clients being weaned from a tube because it allows a client to breathe nasally as he or she relearns a normal breathing pattern. Placement of an inner cannula piece into the tracheostomy tube allows the fenestrated opening to be closed off. With the inner cannula removed, a trachea button may be used to allow the client to talk. A nonfenestrated tube has no opening. A fenestrated tube is preferred for treating a client with dysphagia.

FIGURE 27-4 Tracheostomy tube components. (From Logemann J: Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders, Austin, TX, 1998, Pro-Ed.)

FIGURE 27-5 A, Midsagittal section of the head and neck showing the position of an uncuffed tracheostomy tube. B, Midsagittal section of the head and neck showing the passage of air between the tracheostomy tube and the tracheal wall. (From Logemann J: Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders, Austin, TX, 1998, Pro-Ed.)

A tracheostomy tube may be cuffed or uncuffed. A cuffed tube has a balloon-like cuff surrounding the bottom of the tube.28,43 When inflated, the cuff comes into contact with the trachea wall, preventing the aspiration of secretions into the airway. A cuffed tube is used in cases in which aspiration has occurred. The therapist should consult with the client’s attending physician to see whether the client is still at risk of aspiration or if it is safe to deflate the cuff for an eating and swallowing assessment.

The presence of a tracheostomy tube may affect a client’s swallow because secretions increase, laryngeal mobility decreases, the oropharynx and larynx are desensitized, cough effectiveness is reduced, subglottal air pressure is reduced, and there is disuse atrophy of the laryngeal muscles.63 However, a tracheostomy in and of itself has not been proven to increase the risk for aspiration.40,62

Before the therapist presents food or liquid to the client with a tracheostomy who has a fenestrated tube, the inner cannula should be in place. If the client has a cuffed tube, the therapist should thoroughly suction orally and around the cuff, present food, and slowly deflate the cuff while suctioning to prevent substances from penetrating the airway. The airway again needs to be suctioned orally and through the tracheostomy to ensure that all secretions have been cleared.43 The nursing staff or a therapist who has been trained and is considered competent can perform the suctioning procedure.

After presenting food or liquids, the therapist should assess oral transit skills and the pharyngeal swallow as previously described. Blue food coloring may be added to food or liquids presented orally if the client is not allergic to dyes.20 This can help the therapist identify aspirated material in the trachea. Use of blue food coloring is contraindicated for critically ill clients.35a,44a The client or the therapist can use a gloved finger to cover the trachea opening and thereby achieve a more normal tracheal pressure,2 which has been shown to improve the pharyngeal swallow.31,63 The effect of tracheostomy occlusion (which must be accompanied by cuff deflation) on reducing aspiration is inconclusive.63

If the tracheostomy tube is cuffed and inflated during the assessment, the cuff is slowly deflated after the client has swallowed. The airway is suctioned through the tracheostomy tube to determine whether any material entered the airway. The swallow assessment should not be continued if material is found in the trachea.43 When the assessment is complete, the airway is thoroughly suctioned. The inner cannula is removed from the fenestrated tube, or the cuff is inflated to the level prescribed by the physician.

The client’s performance on the swallowing assessment determines whether the client is able to participate in a feeding program and which diet texture is the most appropriate to ensure a safe, efficient swallow. The safest consistency is that which the client is able to chew, move through the oral cavity, and swallow with the least risk of aspiration.

Indicators of Eating and Swallowing Dysfunction

Symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia include (but are not limited to) the following:21,42

1. Difficulty with bringing food to the mouth

2. Difficulty or inability to shape food into a cohesive bolus-prolonged chewing

3. Coughing or frequent throat clearing before, during, or after the swallow

4. Wet or gurgling voice quality after eating or drinking

5. Changes in mealtime behaviors

Food residue remaining in the mouth (cheeks, gums, teeth, tongue)

Loss of appetite; dehydration or weight loss

Discomfort or pain when swallowing

The presence of any swallowing dysfunction can lead to aspiration pneumonia. The following are acute symptoms of aspiration occurring immediately after the swallow:28

During the 24 hours immediately after the swallow, the therapist and medical staff must observe the client for additional signs of aspiration. These may be a nasal drip, an increase in profuse drooling of a clear liquid, and temperatures of 100° F or greater, which may not have been evident during the clinical examination.28 If aspiration pneumonia develops, the client must be reevaluated for a change in diet levels or taken off the feeding program, if necessary. An alternative feeding method may be necessary to ensure adequate hydration and nutrition.

Instrumental Assessment

Instrumental assessments are important techniques for evaluating biomechanic and physiologic function and for determining swallow safety as well as assessing the effects of compensatory strategies (i.e., posture and bolus texture) on swallowing. They are performed in conjunction with the clinical bedside assessment to rule out or identify silent aspiration. Silent aspiration may not always be accurately identified solely through a clinical bedside assessment. Studies have shown that 2% to 25% of clients with acute stroke52 and up to 50% or more with neurologic impairment11,25 are found to be silent aspirators during instrumental assessment. Aspiration can occur before the swallow because of poor tongue control, pooled material in the valleculae, or a delayed or absent swallow response. Poor laryngeal closure can result in aspiration during the swallow. Aspiration after the swallow is the result of pooled material in the pyriform sinuses or in the valleculae overflowing into the trachea. Understanding why a client is aspirating can help the occupational therapist plan appropriate intervention. Instrumental evaluations provide valuable information about a client’s swallow during a specific period of time, under specific conditions. This information must be considered as part of the complete evaluation process, which includes the bedside assessment and client performance during intervention sessions and meal activities.58,59

The two most common instrumental evaluations used, videofluoroscopy (VFSS) and fiberoptic endoscopy (FEES), are described next.

Assessment with Videofluoroscopy

The videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) is the most commonly used instrumental assessment tool to examine oropharyngeal swallowing disorders. This assessment uses fluoroscopy to capture the client’s swallow with a variety of foods and textures. The VFSS allows the therapist to see the client’s jaw and tongue movement, measure the transit times of the oral and pharyngeal stages, observe the stages of the swallow, note any residue in the valleculae and the pyriform sinuses after the swallow, and identify aspiration. With videofluoroscopy, the therapist can determine the anatomic or physiologic cause of aspiration. Various compensatory techniques may also be assessed to determine if the airway can be protected and if swallow function can be improved, which may allow the therapist to initiate a feeding program.35,43,44 Videofluoroscopy, in conjunction with the clinical assessment, may be used to select appropriate intervention techniques and assist the therapist in determining the safest diet level to help the client achieve a safe swallow.

The VFSS is conducted in the hospital radiology department. Present during the evaluation is the radiologist, the radiology technician, and the swallowing therapist. Equipment necessary for the VFSS includes the fluoroscopy x-ray machine, a monitor for viewing the movement of the bolus in real time. The images are usually videotaped or digitally recorded to allow the radiologist and the therapist to review the recording in slow motion or frame by frame for more in-depth analysis. Other equipment normally available in a radiology department are lead-lined aprons, lead-lined gloves, and foam positioning wedges. Although this VFSS subjects the client to radiation, videofluoroscopy can be performed using minimal radiation doses, with the benefits of assessing oropharyngeal swallow biomechanics and intervention strategies outweighing any risk of exposure to radiation.67

The client is positioned to allow a lateral view, with the fluoroscopy tube focused on the lips, hard palate, and posterior pharyngeal wall. The lateral view is most frequently used because it allows the therapist to evaluate all four stages of the swallow. This view clearly shows the presence of aspiration. A posterior-anterior view also may be needed to evaluate asymmetry in the vocal cords and pooling of the valleculae or pyriform sinuses.

During the VFSS, the therapist presents the client with food or liquid to which barium paste or powder has been added.43,44 The barium contrast allows the bolus to be visible on videofluoroscopy. The therapist mixes or spreads small amounts of paste or powder onto or into each food or liquid consistency. Premixing the consistencies with the barium paste or powder prevents time-consuming interruptions during the actual assessment procedure.

Food and liquids are presented in the same sequence used for the clinical assessment. Starting with pureed foods, the client is given  teaspoon at a time of each consistency and asked to swallow when instructed. Liquids are tested separately, beginning with the thickened substance. Material is given in small amounts to reduce the risks of aspiration. An experienced dysphagia therapist may choose to use only foods or liquids that the client had difficulty with during the clinical examination, rather than to proceed through the entire sequence. The therapist continues to present each consistency to determine if the client can swallow safely and efficiently without aspirating. If aspiration occurs, the therapist should try compensatory strategies and reassess with the same texture. If aspiration occurs while using the strategies, the assessment with this texture is discontinued.

teaspoon at a time of each consistency and asked to swallow when instructed. Liquids are tested separately, beginning with the thickened substance. Material is given in small amounts to reduce the risks of aspiration. An experienced dysphagia therapist may choose to use only foods or liquids that the client had difficulty with during the clinical examination, rather than to proceed through the entire sequence. The therapist continues to present each consistency to determine if the client can swallow safely and efficiently without aspirating. If aspiration occurs, the therapist should try compensatory strategies and reassess with the same texture. If aspiration occurs while using the strategies, the assessment with this texture is discontinued.

The videofluoroscopy procedure can also be used to observe for fatigue of the oral or pharyngeal musculature or the swallow reflex. The client is asked to take repeated, or serial swallows of solids and liquids. The therapist also assesses the client’s ability to control mixed consistencies of solids and liquids such as soups with broth and bits of vegetables, as well as the client’s ability to alternate between solids and liquids. The solid and liquid consistency that the client manages without aspiration is selected as the starting point for eating and swallowing intervention. A client aspirating on pureed or soft foods is not suited for an oral program. The client who is aspirating thick liquids is not a candidate for liquid intake.

VFSS is a valuable tool to be used in conjunction with the clinical examination. It can provide the therapist with additional information regarding the client’s difficulties. By identifying silent aspiration, the therapist can feel comfortable with the decisions made in determining a course of treatment. The therapist must keep in mind that VFSS records the client’s performance in an isolated instance and is not a conclusive indicator of the client’s potential ability in a feeding program.45 If a client continues to progress without difficulty, a second study may not be necessary. A second VFSS may be needed, however, to reevaluate a client who previously was unable to safely swallow on video but now shows signs of readiness to participate in a feeding program.43 Contraindications to performing VFSS include a poor level of awareness or poor cognitive status, oral stage problems only, and the physical inability of the client to undergo the test.

When the results of a VFSS test are documented, foods that were presented, problems that occurred at each stage, and the number of swallows taken to clear the food or liquid are recorded. The therapist also should document compensatory strategies or facilitation techniques that worked effectively to elicit a safe swallow or reduce aspiration risk.

Assessment with Fiberoptic Endoscopy

Fiberoptic endoscopy (FEES) is a nonradioactive alternative to the VFSS. FEES allows for direct assessment of the motor and sensory aspects of the swallow. It can be repeated as often as necessary without exposure to radiation. FEES has been shown to be highly effective in detecting aspiration and critical features of pharyngeal dysphagia.17,39,41,56,64

The equipment needed for a FEES includes a flexible fiberoptic nasopharyngolaryngoscope, a portable light source, a video camera, a video recorder, and a monitor. Placed on a rolling cart, this system can be brought directly to the client’s bedside. The therapist passes a flexible fiberoptic tube through the nasal fossa, along the floor of the nose through the velopharyngeal port, ending in the hypopharynx. 65 The scope allows the therapist to observe the oral cavity, the base of the tongue, and the swallowing structures. The client is given foods and liquids. As the client the swallows, the therapist is able to observe on the monitor tongue movement, pharyngeal and laryngeal function both before and after the swallow, and assess for penetration and aspiration.34,41 The results of a thorough assessment determine the course of intervention to increase a client’s ability to safely eat. Upon completion of the entire dysphagia assessment, the therapist should clearly document the client’s strengths, major problems, goals and objectives, and intervention plan. The objectives should be concise and measurable. The intervention plan should include the type of diet needed, the training and facilitation that the client requires, positioning techniques to be used during feeding, and the type of supervision that must be provided. Recommendations should be communicated to the appropriate nursing and medical staff.

Intervention

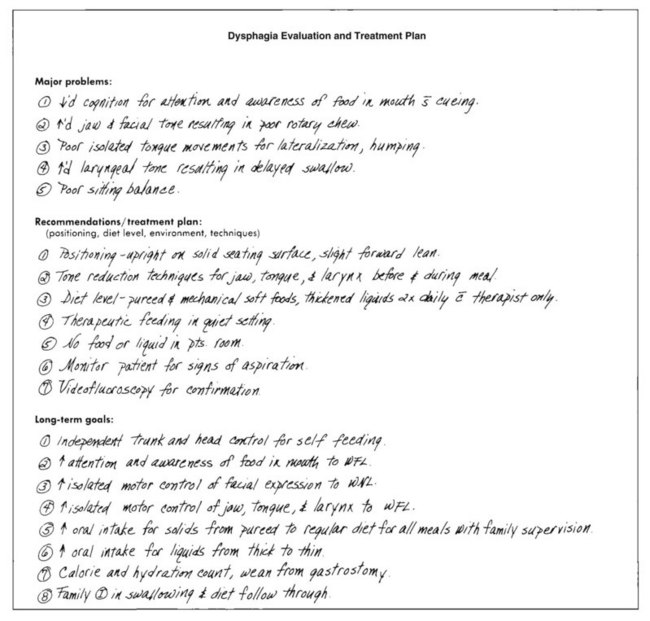

Because a client may display more than one problem at each stage of deglutition, the intervention program for eating and swallowing problems is multifaceted. Intervention for the client with dysphagia involves trunk and head positioning techniques to facilitate oral performance, improve pharyngeal swallow, and reduce the risk of aspiration. The occupational therapist uses clinical reasoning skills to evaluate the interplay of physical, cognitive, environmental, and sociocultural factors that have an impact on feeding, eating, and swallowing.5 Clients with severe problems can require a prolonged course of intervention before they reach optimal recovery.

Intervention falls into two broad categories: rehabilitation techniques and compensatory strategies. Rehabilitation techniques include the use of exercise to improve strength and function. Oral motor exercises are specifically designed to improve the strength and coordination of facial musculature, the tongue and jaw. An effortful swallow in which the client is instructed to swallow with maximal effort either with or without food has been shown to increase tongue base retraction and oral and pharyngeal pressure to improve the swallow.11a Other swallowing maneuvers such as the Mendelsohn maneuver, the Masako maneuver, and the Shaker head lift are rehabilitative techniques used to physically change swallow function. Compensatory swallowing strategies increase swallow safety and decrease the client’s symptoms, such as aspiration, but do not change the physiology of the swallow. Postural techniques such as those listed in Table 27-5 have been found to be effective in redirecting bolus flow and reducing aspiration risk.5,7 Rehabilitative techniques and compensatory strategies are often both used during the client’s therapy program.

TABLE 27-5

Postural Techniques Used in Dysphagia Management

| Problem | Posture | Rationale |

| Impaired oral transit | Head back | Utilizes gravity to clear oral cavity |

| Delay in triggering of pharyngeal swallow | Chin down | Widens valleculae to prevent bolus from entering airway; narrows airway entrance; pushes epiglottis posteriorly |

| Residue in valleculae after the swallow | Chin down | Pushes tongue base backward |

| Reduced laryngeal closure | Chin down, head rotated to weak side | Narrows laryngeal entrance, increases vocal fold closure |

| Reduced pharyngeal contraction (residue in pharynx) | Lying down on side | Eliminates gravitational effect in pharynx |

| Unilateral oral and pharyngeal weakness | Head tilt to stronger side | Directs bolus down stronger side |

| Cricopharyngeal dysfunction (residue in pyriform sinuses) | Head rotated | Pulls cricoid cartilage away from posterior pharyngeal wall, reducing resting pressure in cricopharyngeal sphincter |

Adapted from Logemann J: Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders, Austin, TX, 1998, Pro-Ed.

Goals: The overall goals of OT in the remediation of eating and swallowing dysfunction are as follows:*

1. Facilitation of appropriate positioning during eating

2. Improvement of motor control at each stage of swallow, through normalization of tone and the facilitation of quality movement

3. Maintenance of an adequate hydration and nutritional intake

5. Reestablishment of oral eating to the safest, optimum level on the least restrictive diet

Team Management

Because of the complex nature of dysphagia treatment, the client’s optimal progress is facilitated by the use of a team approach.16,28,42 The dysphagia team should include the client’s attending physician, the occupational therapist, the dietitian, the nurse, the physical therapist, the speech-language pathologist, the radiologist, and the client’s family. Each professional contributes expertise to facilitate client improvement. All members of the dysphagia team should have training and knowledge for working with clients with dysphagia. Interdepartmental in-service education is frequently required so that team members have a similar frame of reference.

The occupational therapist’s role is to select, administer, and interpret assessment measures; develop specific intervention plans; and provide therapeutic interventions.5 The American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA] has prepared a document, Specialized Knowledge and Skills in Feeding, Eating, and Swallowing for Occupational Therapy Practice, that describes the knowledge and skills that occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants should have to provide comprehensive feeding, eating, and swallowing management and services.5 The occupational therapist may also be responsible for coordinating the team effort, which includes obtaining physician’s orders as needed, communicating with other team members and staff, providing family education to ensure proper follow-through, and selecting the appropriate diet.

The attending physician’s role involves the medical management of the client’s health and safety. The physician gives the orders for clinical and instrumental assessments and approves intervention and program recommendations. He or she oversees all decisions regarding treatment for diet level selection, oral and non-oral feeding procedures, and the progression of treatment as recommended by the team. The physician also reinforces the course of treatment with the client and the family.28,30

The dietitian is responsible for monitoring the client’s caloric intake. He or she makes recommendations to ensure that the client receives a balanced, nutritional diet in accordance with the medical condition. The dietitian is involved in suggesting types of feeding formulas for the non-oral client. Diet supplements to augment oral intake may be recommended. In conjunction with the dysphagia team, the dietitian ensures that the client receives the proper food and liquid consistencies. Additional training may be necessary for the dietary staff, because dysphagia diets vary from traditional medical diets.

The client’s physical therapist is involved in muscle reeducation and tone normalization techniques. The client receives treatment in balance, strength, and control. The physical therapist and the occupational therapist collaborate on positioning options. The physical therapist is involved in increasing the client’s pulmonary status for breath support, chest expansion, and cough.

The role of the speech-language pathologist (SLP) involves reeducating the oral and laryngeal musculature used in speaking, voice production, and swallowing. The SLP is a key member of the dysphagia team.7

The nurse is another important member of the dysphagia team. The nursing staff is responsible for monitoring the client’s medical and nutritional status. Nurses who are available on a 24 hour basis in the hospital setting and who are trained in dsyphagia screening are in a key position to administer initial swallowing screenings.33 The nurse usually is the first to notice changes in the client’s condition, such as an elevated temperature; an increase in pulmonary congestion; and an increase in secretions, which indicates swallowing dysfunction.28 The nurse informs the physician and the dysphagia team of these changes. The client’s oral and fluid intake is recorded in the nursing notes, and the nurse notifies the dysphagia team when the client’s nutritional status is adequate or inadequate. The nursing staff members administer supplemental tube feedings that have been ordered by the physician; the staff also provides oral hygiene, tracheostomy care, and supervision for appropriate clients during meals.28,33

The client’s family is included on the team to act as program supporters. Families frequently underestimate the danger of aspiration. Therefore, both the family and the client must be educated, beginning with the first day of assessment. The family and client should understand which food consistencies are safe to eat and which foods must be avoided.2,4

The roles of the team members may vary from one treatment facility to another. Designated roles must be clearly defined to ensure a coordinated team approach. Therapists who are responsible for direct treatment should have advanced knowledge and training in dysphagia treatment procedures.

Positioning

Proper positioning is essential when working with the client who has dysphagia.28 The client should be positioned symmetrically with normal alignment between the head, neck, trunk, and pelvis. The ideal position is as follows:

1. The client is seated on a firm surface, such as a chair.

2. The client’s feet are flat on the floor.

3. The client’s knees are at 90-degree flexion.

4. There is equal weight bearing on both ischial tuberosities of the hips.

5. The client’s trunk is flexed slightly forward (100-degree hip flexion) with the back straight.

6. Both of the client’s arms are placed forward on the table.

7. The head is erect, in midline, and the chin is slightly tucked.

For the client who may be restricted to bed but is able to sit in a semireclined position, the same positioning principles apply: equal weight bearing on both ischial tuberosities for the hips, the trunk flexed slightly forward (100-degree hip flexion) with the back straight, knees slightly flexed, and both arms placed forward on a bedside table. The head and neck should be aligned appropriately to reduce the risk of aspiration.

For the client who must remain completely supine in bed, oral feeding is generally contraindicated. If the client can be positioned sidelying in bed, appropriate head and neck alignment must be achieved before the assessment of feeding skills. The client’s knees and hips should be slightly flexed and trunk aligned while supported in the sidelying position. The use of additional pillows, rolls, and supports may be required to maintain the appropriate alignment.

Mattias was able to sit in a chair and responded well to physical prompts to sit aligned with both arms supported on the tabletop. Although he was concerned that resting his arms on the table was impolite, his therapist suggested using a chair with armrests. He typically would slightly extend his neck when attempting to swallow foods, and using the technique of a slight chin tuck diminished the coughing and choking episodes when he ate textured foods.

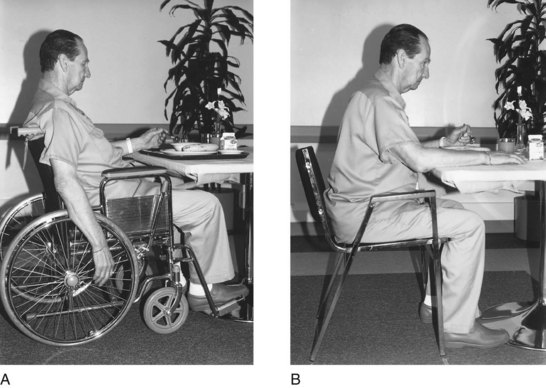

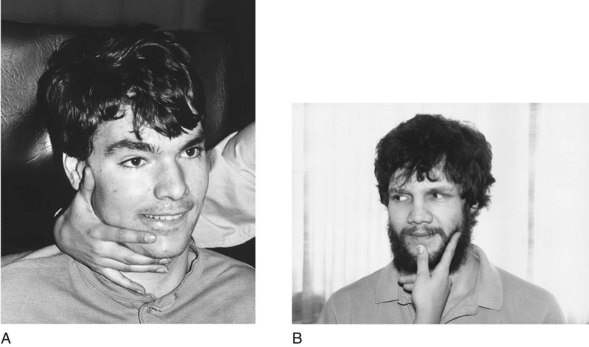

Figure 27-6 shows two different supportive positions that allow the therapist to help the client maintain head control. Correct positioning allows more appropriate muscular action, which thereby facilitates quality motor control and function of the facial musculature, jaw and tongue movement, and the swallowing process, all of which minimize the potential for aspiration.

FIGURE 27-6 Head control. A, Side hold position for clients requiring maximum to moderate assistance. B, Front hold position for clients requiring minimal assistance. (Courtesy Meadowbrook Neurological Care Center, San Jose, CA, 1988.)

A client who has difficulty moving into the correct position or maintaining the position presents a challenge to the occupational therapist. A careful analysis of the client is needed to determine the major problem preventing proper positioning. Poor positioning may be a result of decreased control, strength or balance secondary to hypertonicity, hypotonicity, or weakness or poor body awareness in space secondary to perceptual dysfunction (Figure 27-7).26 After the cause is identified, the therapist develops intervention to address the specific problems. Treatment suggestions are described later in this chapter. To assist in maintaining trunk position, the therapist may consider the use of an adaptive lateral trunk support. Seating the client at a table provides forward trunk support.

Oral Hygiene

Oral care by nursing and therapy team members prevents gum disease, the accumulation of secretions, the development of plaque, and the aspiration of food particles that remain after eating. Poor or inadequate oral hygiene has been linked with healthcare-associated pneumonia, respiratory tract infections, and influenza in elderly people.27,47,57 The client who is hypersensitive or resistant to having anything in the mouth may require intervention from the occupational therapist. Preparation steps may include firmly stroking outside the client’s mouth or lips with the client’s or therapist’s finger. Sensitive gums can also be firmly rubbed, preparing the client for the toothbrush.

For cleaning purposes, the mouth can be divided into four quadrants. A toothbrush with a small head and soft bristles is used to clean each quadrant, starting with the top teeth and moving from front to back. When brushing the bottom teeth, the therapist brushes from back to front. Next, holding the toothbrush at a vertical angle, the therapist brushes the inside teeth downward from gums to teeth. Finally, the cutting surfaces of the teeth are brushed. An electric toothbrush can be more effective, if the client can tolerate it.

After each procedure the client is allowed to dispose of secretions. After brushing, the client is carefully assisted in rinsing the mouth. If the client can tolerate thin liquids, small amounts of water can be given. Having the client flex the chin slightly toward the chest helps prevent the water from being swallowed. The therapist can help the client expel the water by placing one hand on each cheek and simultaneously pushing inward on the cheeks while the chin remains slightly tucked. If the client has no ability to manipulate liquids, a dampened sponge toothette can be used.