Chapter 11 Audit

Introduction: what is audit?

Audit concerns the quality of professional activities and services. Audit is carried out to determine whether best practice is being delivered and, equally importantly, to improve practice. Audit is part of clinical governance (see Ch. 8) – probably the key part – therefore it forms part of the quality improvement work which takes place within all NHS organizations. It can be described as ‘improving the care of patients by looking at what you do, learning from it and if necessary, changing practice’.

Audit is based around standards of practice. The hallmark of a professional is that they maintain standards of professional practice, which exist to protect the public from poor-quality services. Audit provides a method of accountability, both to the public and to government, which demonstrates that standards are being met or, if not, that action is being taken to remedy the situation. It also provides managers with information about the quality of the services their staff deliver. Although this may seem somewhat threatening, ultimately the aim of audit is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of services, to promote higher standards and to improve the outcome for patients. It also allows changes in practice to be evaluated. Therefore it is an essential component of any professional’s work and an integral part of day-to-day practice.

Most healthcare professionals’ activities have an impact on patients, either directly or indirectly, so can be described as a clinical service. Audit of these services is therefore clinical audit. Clinical audit is defined by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) as ‘a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through systematic review of care against explicit criteria and the implementation of change’. All NHS trusts in the UK must support audit, so should have a central audit office which provides training and help in designing audits and collates the results of clinical audits. All NHS staff are expected to participate in clinical audit. Community pharmacists are required to participate in two clinical audits each year, one based on their own practice and one multidisciplinary audit organized by their local primary care organization.

There are actually few instances where pharmacists provide a clinical service to patients in isolation from other healthcare professionals. The provision of advice and sale of non-prescription medicines may be one such area, but most services will impact on or be affected by service provision by other professionals, so can be regarded as multidisciplinary. The audit of these clinical services should ideally also be multidisciplinary. The users of services should also be involved in audit whenever possible, perhaps by asking patient representatives to join the audit team. They can provide important insight into what aspects of a service would benefit from audit and can help to set the criteria against which performance will be audited.

Relationship between practice research, service evaluation and audit

It is important to understand the relationship between practice research, service evaluation and audit. Practice research is designed to establish what is best practice. An example of this would be a randomized controlled trial of pharmacists undertaking a new service compared to normal care. In a controlled trial, patients are often carefully selected, using inclusion and exclusion criteria, special documentation and outcome measures are used which may differ from those used in routine practice and all aspects of the service being studied must be standardized.

To implement a new service into routine practice further development will be required. Many aspects of a new service are likely to differ from those used in a research situation and may differ between practice settings. All new services will then need to be evaluated, which may involve determining the views of service providers and users, collecting data on the outcomes for patients who use the service and finding out if publicity is adequate. Changes may be necessary if problems are identified in service evaluation.

Once a service is running smoothly it should then be subject to audit. This will involve setting standards for the service and measuring actual practice against these standards. Findings from research and service evaluations can contribute to standard setting in audit.

Although there are many similarities in the methods used to obtain data for research and for audit, there are important differences. In research, it is important to have controlled studies, to be able to extrapolate the results and to have large enough samples to demonstrate statistical significance of any differences between groups. None of these applies to audit. Audit compares actual practice to a predetermined level of best practice, not to a control. The results of audit apply to a particular situation and should not be extrapolated. Audit can be even applied to a single case; large numbers are not required.

Types of audit

Audit may be of three types, depending on who undertakes it. These are:

Self-audit is undertaken by individuals and is part of a professional work attitude in which critical appraisal of actions taken and of their results is constantly being made. While anyone can do self-audit, it is most likely to be used by pharmacists who work in isolation, such as in single-handed community pharmacies. There are many examples of self-audits, such as those on availability of leaflets, facilities within the pharmacy, owing items and patient counselling, which fulfil the requirements of the pharmacy contract. See the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) website for audit packs on these topics.

Peer audit is undertaken by people within the same peer group, which usually means the same profession. Peer audit involves joint setting of standards by an audit team. For example, pharmacists from several hospitals which provide similar services could get together and audit each other’s service. In primary care, pharmacists within or between primary care trusts (PCTs) could compare their practices. Another way of doing this is benchmarking – a process of defining a level of care set as a goal to be attained. Here standards are set against those identified by a leading centre, such as a teaching hospital.

External audit is carried out by people other than those actually providing the service and so is perceived as threatening by those whose services are being audited. It may be more objective in its criticisms than self or peer audit, but there may be less enthusiasm for corrective action to improve services. If standards are imposed, there is a perceived threat if an individual’s performance is not of the standard required. It is possible to involve those whose services are to be audited in deciding what best practice should be and in making improvements to make external audit more acceptable. NHS services are subject to external audit carried out by the Healthcare Commission, which conducts national audits in England and Wales. The data produced enable comparisons to be made between different NHS trusts and enable sharing of good practice.

Multidisciplinary audit is the most common type of group audit and is usually preferred for clinical audit, but it is essential to ensure that one subgroup is not auditing the activities of another subgroup. This would lead to tensions and be counterproductive. For example, in an audit of doctors’ prescribing errors detected by pharmacists, pharmacists cannot set the standard for an acceptable level of errors without the involvement of the doctors. If they are not part of the audit team, there is little chance of improvement. Pharmacists are often involved in carrying out audits of clinical practice, for example audit of prescribing against NICE clinical guidelines. In this situation, it is also important that the prescribers are involved in setting the standards.

What is measured in audit?

There are three aspects of any services and activities which can be audited. These are:

Structures are the resources available to help deliver services or carry out activities. Examples are staff, their expertise and knowledge, books, learning materials or training courses, drug stocks, equipment, layout of premises.

Processes are the systems and procedures which take place when carrying out an activity and may include quality assurance procedures and policies and protocols of all types. Examples are: procedures for dealing with patients’ own medicines in hospital, prescribing policies and disease management protocols.

Outcomes are the results of the activity and are arguably the most important aspect of any activity. In pharmaceutical audits such as drug procurement or distribution or standards of premises, outcomes should be easily identified and measurable. In many clinical audits, some outcomes are relatively easily measured, for example changes in parameters such as blood pressure, INR (international normalized ratio) control and serum biochemistry. Surrogate outcomes can also be used, such as the drugs or doses prescribed. However, outcomes which involve a change in health status, attitude or behaviour may be very difficult to measure.

Any individual audit can examine structures, processes and outcomes individually or together.

The audit cycle

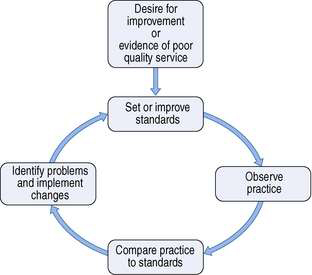

Audit is a continuous process, which follows a cycle of measurement, evaluation and improvement. The basic cycle is shown in Figure 11.1, but audit can also be seen as a spiral in which standards are continuously raised as practice improves.

Before starting an audit, first identify its purpose. This will derive from the desire to improve the quality of the service. For example, the purpose may be ‘to improve the dispensing turnround time’ or ‘to increase the proportion of patients counselled about their new medicines’. It may be appropriate to conduct a ‘baseline audit’ to find out if indeed there is a need to improve service quality. A baseline audit is a small study in which data are collected before standards are set. Once it is known that there is a need to improve services, the audit cycle incorporates:

Although the process is continuous, it is not practicable to audit all activities or services all the time. A baseline audit may help to decide whether improvements are possible and routine monitoring may be instituted instead of repeat audits to ensure that best practice, once attained, is maintained.

Setting standards

All audits should be based on standards which are widely accepted (i.e. best practice). The Medicines, Ethics and Practice guide may help to set standards for many aspects of pharmacy services. Other documents can also be used to develop standards, such as national service frameworks, practice guidelines or clinical guidelines for individual medical conditions. Several standards are usually set for any individual audit, relating to resources, processes or outcomes.

Because audit is about comparing actual practice to standards of best practice, numerical values need to be added which will allow this. A guideline may suggest a criterion, for example that patients receiving warfarin should be counselled about avoiding aspirin. For this to form a useful standard for audit, it needs to be clarified whether this applies to all patients, i.e. 100%. This numerical value is the target, which, together with the criterion, forms the standard or ‘level of performance’. It is then easy to measure whether this occurs in practice. Many clinical guidelines suggest audit standards and criteria.

A target level of 100% is termed an ideal standard but this may not be achievable. The level set may need to be a compromise between what is desirable and what is possible, since resources may be limited. This would be an optimal standard. Using the previous example, it may be considered at the outset that there are insufficient staff to ensure that 100% of patients receiving warfarin could be counselled about avoiding aspirin. A compromise could be that 100% of patients prescribed warfarin for the first time receive this advice. Another type of standard is the minimal standard, which, as its name implies, is the minimum acceptable level of service and is often used in external audits.

If there are no published guidelines or standards, they will need to be devised. This may involve searching the literature, for example recent journals, textbooks or educational material. Whether devising standards from scratch or making guidelines into standards, it is important that the whole audit team is involved in devising them. This may include doctors, nurses, health visitors, technical staff and non-medical staff, such as receptionists or porters, and patients or their carers. Inclusion avoids the potential feeling of threat which may be created by audit. Anyone excluded at this stage would perceive the audit as external, and refuse to help improve performance, which could mean the whole exercise is a waste of time.

Once standards have been set, the next stage of audit involves collecting data on actual practice.

Observing practice

Many audits require a simple form onto which data from other sources are transferred. In audits involving structures, checklists are often most useful; those involving processes may use checklists or may need space for other types of data, while auditing clinical outcomes may require additional methods such as questionnaires. As with any data collection, it is important that the information obtained is able to answer the questions asked. In the case of an audit, the question(s) may be relatively simple, such as ‘What percentage of patients receiving warfarin are counselled?’

It is often useful to incorporate some measure of potential factors which may influence practice within the data collection. So, in addition to finding out whether local clinical guidelines are being used by examining medical records, it is worth issuing a questionnaire to those expected to use the guidelines to find out their views on whether the guidelines are readily available, are in an acceptable format and meet their needs. In an audit of warfarin counselling, it is useful to collect data on how busy the pharmacy is when each patient presents their prescription and how many staff trained to provide advice were available. This may mean that the data collection procedures may need to anticipate some potential causes of failing to provide best practice.

Before setting out to devise a data collection form, it is always worth finding out whether a similar audit has been done before, so you can adapt or modify the data collection procedures used. Some useful data collection sheets for a wide range of audits are available from the RPSGB website. These include audits of pharmacy processes such as prescription waiting times, responding to symptoms and referrals to GPs. If you do need to design a new procedure, the data collection must fulfil some basic requirements (Box 11.1). First the data collected must be able to address the purpose of the audit. The method of data collection must be valid and reliable. If sampling procedures are used, they too must be appropriate, avoiding bias and, equally importantly, it must be feasible to carry them out.

Validity is the extent to which what is measured is actually what is supposed to be measured. To use the warfarin counselling example again, the standard was about advice concerning aspirin. If the only data collected involved the number of patients who were counselled and not what advice they were given about aspirin, these data would be invalid, since they did not measure what they set out to measure.

Reliability is a measure of the consistency or reproducibility of the data collection procedure. Good reliability can be difficult to achieve when trying to measure outcomes in health care. It is therefore important to use recognized measures wherever possible. Reliability may also vary among individuals collecting data, despite their using the same data collection tool. It is important to check this and ensure that they are doing the same thing before they start to collect data.

Sampling is important in collecting data for audit, because the data should be unbiased and representative of actual practice. It may be that the numbers and time involved are small enough that all examples of the activity are included in data collection procedures. In the case of large numbers, it may be easier to include just a proportion in the audit. If so, a plan is needed which ensures that those selected are representative. Many different sampling methods could be used, including random (using number tables or computer) or systematic (such as every tenth patient presenting a prescription for warfarin). Another way is to decide in advance that a certain percentage of the total population (a quota) will be sampled, usually ensuring that they will be typical of the population in important characteristics. These techniques require that the total population size within the audit period is known. A large population may also need to be stratified into subgroups first before sampling, for example patients with new prescriptions and patients with repeats.

Sampling, or even large numbers, may not always be necessary. Since audit is about a particular service or activity, carried out by one or more particular individual professionals, an audit can be carried out on a service provided to one patient. It is still the determination of whether actual practice equates to best practice.

Feasibility of data collection is very important. It must be possible to collect the data required to answer the question. It is often necessary to incorporate data collection for audit into routine work, so the time taken is an important consideration. Some data may already be collected on a routine basis, which can be used to answer audit questions. Data kept on patient medication records or on medicine use review (MUR) records may be useful for some audits. Some pharmacies routinely log the time when prescriptions are handed in and given out, so an audit of turnaround time could easily be carried out using these data. Hospitals routinely collect data on length of stay and number of admissions, discharges and deaths, which may be useful outcome measures. Often data have to be specially collected for the audit, which is where the data collection tools come in.

Data for audit can be either quantitative or qualitative in nature. Qualitative data are often useful in obtaining opinions about services or for measuring outcomes in patients. Large numbers are not required for producing qualitative data. It may be useful to undertake qualitative work which can then be used to help design a good data collection tool to be used in a quantitative way, using larger numbers. Quantitative audit may generate large amounts of data, which require subsequent analysis, usually using statistics. These may be purely descriptive or simple comparative statistics.

Whether the data collected are retrospective or prospective depends to a large extent on the topic of the audit and the data available. Retrospective audit can only be undertaken if good records of activities have been kept. Prospective audits should ensure that the data required are recorded, even if only for the audit period. There is a possibility of practice changing during the audit period simply because the audit is being undertaken. This may not always be a problem if practice is better than usual and if audit is continuous, since the ultimate aim is to improve services. It is more important to be aware of this effect if practice is measured periodically, although it is very difficult to control for.

In large audits, piloting the data collection tool using a sample similar to those to be included in the audit is a valuable way of finding out if it is suitable. This should avoid the discovery that there were difficulties in interpretation or that vital information has not been recorded after acquiring large amounts of data.

Comparing practice to standards

This is the evaluation stage of audit, in which actual practice is compared to best practice. First the data obtained must be analysed and presented. Most audit data require only descriptive analysis, such as percentages, means or medians, along with ranges and standard deviations to show the spread of the data. Comparative statistical tests are useful for looking at one or more subgroups of quantitative data. This could be for different data collection periods (audit cycles) or for subgroups within one audit. Examples where comparison may be useful are three different pharmacies’ prescription turnaround times or the counselling frequencies for patients presenting prescriptions for warfarin for the first time compared to those who have taken it before. The statistical test must be appropriate for the type of data. Chi-square is used for nonparametric data, such as frequencies. For parametric data which are normally distributed, t-tests can be used. When statistics are used in an audit, it is important to consider the practical significance of the data. An improvement which is statistically significant may not always be of practical significance and vice versa. In presenting data, graphics can be particularly useful, as tables can be discouraging to many people. This is particularly important in a group audit, where everyone needs to see the results. Simple graphics, such as pie charts or bar charts, should be adequate.

Data collected for audit purposes relate to the activities of individual professionals and to their effects on patients. It is therefore essential to maintain confidentiality. Permission is required before any information about one individual’s practice is given to other members of the audit team. Managers who may need this sort of information should be part of the audit team anyway. The general results of an audit should, however, be made available to others, after ensuring that no individual practitioner or patient can be identified. This is essential if the audit is to improve services, as it will help others to learn and allow comparisons to be made.

When comparing the results of audits between centres, there will most probably be differences – perhaps in staffing levels, population served, case mix and so on – which could account for differences in apparent performance. Any unusual situations which occurred during the audit and which may have affected performance should be highlighted. Also any errors in data collection must be identified, which may mean data have to be excluded from analysis as they could be unrepresentative of what should have happened. It is most important to remember that the results of any audit should not be extrapolated beyond the sample audited. Audit applies to a particular activity, carried out by particular individuals and involving particular patients.

Providing the standards for the audit have been set appropriately, it should be relatively easy to determine whether they have been achieved. Often the most difficult part of audit is finding out why best practice is not being delivered and ensuring that improvement occurs.

Identifying problems

It is little use simply finding out that a service fails to meet a given standard. The underlying causes of failure need to be established and the data collection procedures should have attempted to identify some of these. Suboptimal practice can arise for a variety of reasons, such as inadequate skills or knowledge, poor systems of work or the behaviour of individuals within a team. Each should be examined as a possible contributory factor to disappointing results of an audit. Simple lack of awareness, for example, about local clinical guidelines can contribute to their lack of use. Lack of skill may be related to infrequency of carrying out a particular activity. Both are relatively easily remedied. Both behaviour and the way in which work is organized are more difficult to change. The strategies adopted for effecting change will need to differ depending on which of these underlying causes is present.

Implementing changes

Achieving improvement in practice requires a change in behaviour. Change can be threatening simply because of its novelty. It may also involve increased work and is often resisted. This is why everyone whose work pattern may need to change should be active members of the audit team from the start. Change must be seen as leading to improvement in performance and ultimately patient benefit. The changes proposed to improve practice must be closely tailored to the underlying cause of the suboptimal audit results. They should be specific to the situation which has been audited, rather than general. They should be non-threatening and may need to be introduced gradually. Change may require resources, including time. It may also have other knock-on effects which need to be anticipated. The effect of changes must be monitored, to see whether they have been successful. This can be done by re-audit or by continuous monitoring if routinely collected data can be used.

Re-audit

Sometimes it may be appropriate to reconsider the standards before undertaking a further period of data collection.

Standards which were set too high may always be unattainable, although this may not have been apparent before practice was measured. It is equally possible to have used low standards and to have found they were surpassed. In this case it may be appropriate to raise them, which is a good way of improving practice. Whether or not the standards remain the same, a second period of measuring practice is needed if changes have been implemented, so that the effectiveness of these changes can be determined.

It is always difficult to change behaviour and improvements in practice may be short-lived. It may therefore be necessary to repeat audits at regular intervals to reinforce the desired practice and maintain the improvement in service.

Learning through audit

If the prevailing view of an audit which shows performance to be less than the standard set is that there are lots of reasons which could excuse this result, then little has been learned from undertaking the audit. Evaluating your service may be difficult, but it may also teach you a lot about yourself and the staff with whom you work. For example, it is of little use to suggest that the reason there were so many dispensing errors during the audit was that there was a new locum employed for part of the time. It is much more valuable to consider what information you have available for locums about your dispensing procedures and indeed whether your dispensing procedures are adequate.

If the results of an audit were suboptimal, but much as expected, is this because staff have been accepting of poor practices in the past? Have staff been aware of the need for improvements in systems but felt unable to suggest changes? Have staff been wanting more training but known that there is no money available to pay for it? All these are hypothetical situations, but you can see how conducting audit may have more learning than just what needs to be done to improve services. In this way, carrying out audit can contribute to continuous professional development and so has benefits both for you and, ultimately, for the patient.