Chapter 23 Obstetric Emergencies

Vasa praevia

The term vasa praevia is used when a fetal blood vessel lies over the os, in front of the presenting part. This occurs when fetal vessels from a velamentous insertion of the cord cross the area of the internal os to the placenta. Vasa praevia may sometimes be palpated on vaginal examination when the membranes are still intact. It may also be visualised on ultrasound. If it is suspected, a speculum examination should be made.

Ruptured vasa praevia

When the membranes rupture in a case of vasa praevia, a fetal vessel may also rupture. This leads to exsanguination of the fetus unless birth occurs within minutes.

Management

See Box 23.1.

Box 23.1 Management of vasa praevia

• Monitor the fetal heart rate

• If the mother is in the first stage of labour and the fetus is still alive, an emergency caesarean section is carried out

• If in the second stage of labour, delivery should be expedited and a vaginal birth may be achieved

• A paediatrician should be present at delivery. If the baby is alive, haemoglobin (Hb) estimation will be necessary after resuscitation

Presentation and prolapse of the umbilical cord

See Box 23.2 for definitions.

Cord presentation

This is diagnosed on vaginal examination when the cord is felt behind intact membranes. It is, however, rarely detected but may be associated with aberrations in fetal heart monitoring such as decelerations, which occur if the cord becomes compressed.

Cord prolapse

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made when the cord is felt below or beside the presenting part on vaginal examination.

Diagnosis is made when the cord is felt below or beside the presenting part on vaginal examination.

A loop of cord may be visible at the vulva.

A loop of cord may be visible at the vulva.

Whenever there are factors present that predispose to cord prolapse, a vaginal examination should be performed immediately on spontaneous rupture of membranes. Variable decelerations and prolonged decelerations of the fetal heart are associated with cord compression, which may be caused by cord prolapse.

Whenever there are factors present that predispose to cord prolapse, a vaginal examination should be performed immediately on spontaneous rupture of membranes. Variable decelerations and prolonged decelerations of the fetal heart are associated with cord compression, which may be caused by cord prolapse.

Immediate action and management

See Box 23.4.

Box 23.4 Management of cord prolapse

Immediate action

• If an oxytocin infusion is in progress, this should be stopped

• A vaginal examination is performed to assess the degree of cervical dilatation and identify the presenting part and station. If the cord can be felt pulsating, it should be handled as little as possible

• If the cord lies outside the vagina, replace it gently to try to maintain temperature

• Auscultate the fetal heart rate

• Relieve pressure on the cord

• Keep your fingers in the woman’s vagina and, especially during a contraction, hold the presenting part off the umbilical cord

• Help the mother to change position so that her pelvis and buttocks are raised. The knee–chest position causes the fetus to gravitate towards the diaphragm, relieving the compression on the cord

• Alternatively, help the mother to lie on her left side, with a wedge or pillow elevating her hips (exaggerated Sims’ position)

• The foot of the bed may be raised

• These measures need to be maintained until the delivery of the baby, either vaginally or by caesarean section

• Consider inserting 500 ml of warm saline into the bladder to relieve the pressure if transfer to an obstetric unit is required

Treatment

• Delivery must be expedited with the greatest possible speed

• Caesarean section is the treatment of choice if the fetus is still alive and delivery is not imminent, or vaginal birth cannot be indicated

• In the second stage of labour the mother may be able to push and you may perform an episiotomy to expedite the birth

• Where the presentation is cephalic, assisted birth may be achieved through ventouse or forceps

Shoulder dystocia

Definition

The term ‘shoulder dystocia’ is used to describe failure of the shoulders to traverse the pelvis spontaneously after delivery of the head. The anterior shoulder becomes trapped behind or on the symphysis pubis, while the posterior shoulder may be in the hollow of the sacrum or high above the sacral promontory. This is, therefore, a bony dystocia, and traction at this point will further impact the anterior shoulder, impeding attempts at delivery.

Warning signs and diagnosis

The birth may have been uncomplicated initially, but the head may have advanced slowly and the chin may have had difficulty in sweeping over the perineum. Once the head is born, it may look as if it is trying to return into the vagina.

Shoulder dystocia is diagnosed when manoeuvres normally used by the midwife fail to accomplish birth.

Management

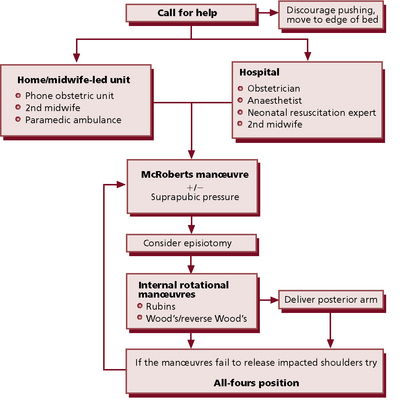

See Box 23.5 and Figs 23.1–23.3.

Box 23.5 Management of shoulder dystocia

• Summon help – an obstetrician, an anaesthetist and a person proficient in neonatal resuscitation

• Attempt to disimpact the shoulders and accomplish delivery. An accurate and detailed record of the type of manoeuvre(s) used, the time taken, the amount of force used and the outcome of each attempted manoeuvre should be made

• Try the procedures for 30–60 seconds; if the baby is not born, move on to the next procedure

Non-invasive procedures

• McRoberts manœuvre. Involves helping the woman to lie flat and to bring her knees up to her chest as far as possible to rotate the angle of the symphysis pubis superiorly and use the weight of her legs to create gentle pressure on her abdomen, releasing the impaction of the anterior shoulder

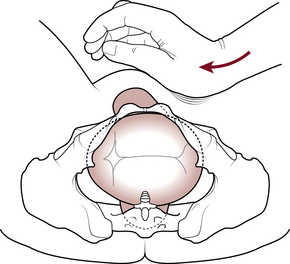

• Suprapubic pressure (Fig. 23.1). Pressure is exerted on the side of the fetal back and towards the fetal chest to adduct the shoulders and push the anterior shoulder away from the symphysis pubis. Can be used with the McRoberts manoeuvre.

Manipulative procedures

Where non-invasive procedures have not been successful, direct manipulation of the fetus must now be attempted:

• Positioning of the mother. McRoberts or the all-fours position may be used

• Episiotomy. May be necessary to gain access to the fetus and reduce maternal trauma

• Rubin’s manoeuvre. The posterior shoulder is pushed in the direction of the fetal chest, thus rotating the anterior shoulder away from the symphysis pubis into the oblique diameter

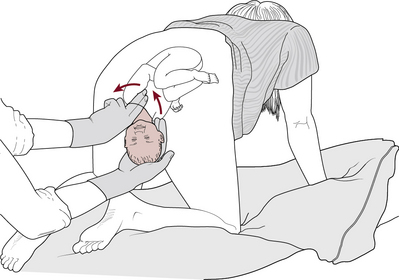

• Wood’s manoeuvre (Fig. 23.2). A hand is inserted into the vagina, pressure is exerted on the posterior fetal shoulder, and rotation is achieved

• Reverse Wood’s manoeuvre. Fingers on the back of the posterior shoulder apply pressure to rotate in opposite direction

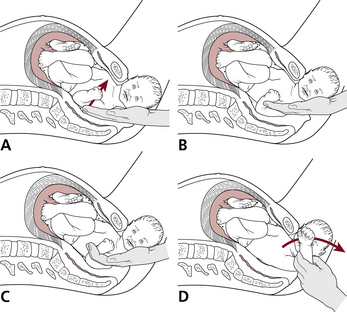

• Delivery of the posterior arm (Fig. 23.3). A hand is inserted into the vagina, and two fingers splint the humerus of the posterior arm, flex the elbow and sweep the forearm over the chest to deliver the hand. If the rest of the delivery is not then accomplished, the second arm can be delivered following rotation of the shoulder using either Wood’s or Rubin’s manoeuvre or by reversing the Løvset manoeuvre. Has a high complication rate

• Zavanelli manoeuvre. If the manoeuvres described above have been unsuccessful, the obstetrician may consider the Zavanelli manoeuvre. Requires the reversal of the mechanisms of delivery so far and success rates vary

Fig. 23.1 Correct application of suprapubic pressure for shoulder dystocia.

(After Pauerstein C 1987, with permission.)

Fig. 23.3 Delivery of the posterior arm. (A) Location of the posterior arm. (B) Directing the arm into the hollow of the sacrum. (C) Grasping and splinting the wrist and forearm. (D) Sweeping the arm over the chest and delivering the hand.

The mnemonic HELPERR is widely used in obstetric drills (Box 23.6). An algorithm (Fig. 23.4) can also be helpful.

Rupture of the uterus

Rupture of the uterus is defined as:

complete rupture – involves a tear in the wall of the uterus with or without expulsion of the fetus.

complete rupture – involves a tear in the wall of the uterus with or without expulsion of the fetus.

incomplete rupture – involves tearing of the uterine wall but not the perimetrium.

incomplete rupture – involves tearing of the uterine wall but not the perimetrium.

The life of both mother and fetus may be endangered in either situation.

Dehiscence of an existing uterine scar may also occur.

Causes

Injudicious use of oxytocin, particularly where the mother is of high parity.

Injudicious use of oxytocin, particularly where the mother is of high parity.

Neglected labour, where there is previous history of caesarean section.

Neglected labour, where there is previous history of caesarean section.

Extension of severe cervical laceration upwards into the lower uterine segment.

Extension of severe cervical laceration upwards into the lower uterine segment.

Trauma, as a result of a blast injury or an accident.

Trauma, as a result of a blast injury or an accident.

Antenatal rupture of the uterus, where there has been a history of previous classical caesarean section.

Antenatal rupture of the uterus, where there has been a history of previous classical caesarean section.

Amniotic fluid embolism/anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy

This rare but potentially catastrophic condition occurs when amniotic fluid enters the maternal circulation via the uterus or placental site. The presence of amniotic fluid in the maternal circulation triggers an anaphylactoid response and the term ‘embolus’ is a misnomer.

The body responds in two phases:

The initial phase is one of pulmonary vasospasm causing hypoxia, hypotension, pulmonary oedema and cardiovascular collapse.

The initial phase is one of pulmonary vasospasm causing hypoxia, hypotension, pulmonary oedema and cardiovascular collapse.

The second phase sees the development of left ventricular failure, with haemorrhage and coagulation disorder and further uncontrollable haemorrhage.

The second phase sees the development of left ventricular failure, with haemorrhage and coagulation disorder and further uncontrollable haemorrhage.

Amniotic fluid embolism can occur at any time, but during labour and its immediate aftermath is most common. It should be suspected in cases of sudden collapse or uncontrollable bleeding. Maternal and fetal/neonatal mortality and morbidity are high.

Acute inversion of the uterus

This is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of the third stage of labour.

Causes

Causes of acute inversion are associated with uterine atony and cervical dilatation, and include:

mismanagement in the third stage of labour, involving excessive cord traction to manage the delivery of the placenta actively

mismanagement in the third stage of labour, involving excessive cord traction to manage the delivery of the placenta actively

combining fundal pressure and cord traction to deliver the placenta

combining fundal pressure and cord traction to deliver the placenta

use of fundal pressure while the uterus is atonic, to deliver the placenta

use of fundal pressure while the uterus is atonic, to deliver the placenta

pathologically adherent placenta

pathologically adherent placenta

Management

See Box 23.7.

Box 23.7 Management of acute inversion of the uterus

Immediate action

• Summon appropriate medical support

• Attempt to replace the uterus by pushing the fundus with the palm of the hand, along the direction of the vagina, towards the posterior fornix. The uterus is then lifted towards the umbilicus and returned to position with a steady pressure (Johnson’s manoeuvre)

• Give hydrostatic pressure with warm saline

• Insert an intravenous cannula and commence fluids. Take blood for cross-matching prior to starting the infusion

• If the placenta is still attached, it should be left in situ as attempts to remove it at this stage may result in uncontrollable haemorrhage

• Once the uterus is repositioned, the operator should keep the hand in situ until a firm contraction is palpated. Oxytocics should be given to maintain the contraction

Basic life-support measures

Before starting any resuscitation, assessment of any risk to the carer and the patient is needed. The basic principles of life support are:

The level of consciousness is established by shaking the woman’s shoulders and enquiring whether she can hear.

Lie the woman flat; if she is pregnant, position with a left lateral tilt to prevent aortocaval compression.

Lie the woman flat; if she is pregnant, position with a left lateral tilt to prevent aortocaval compression.

Airway check – remove obstructions, tilt head back and lift chin upwards.

Airway check – remove obstructions, tilt head back and lift chin upwards.

Breathing – look, listen and feel for up to 10 seconds.

Breathing – look, listen and feel for up to 10 seconds.

Circulation – check carotid pulse; if no pulse felt, commence cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Circulation – check carotid pulse; if no pulse felt, commence cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Shock

Shock can be classified as follows:

Hypovolaemic – the result of a reduction in intravascular volume.

Hypovolaemic – the result of a reduction in intravascular volume.

Cardiogenic – impaired ability of the heart to pump blood.

Cardiogenic – impaired ability of the heart to pump blood.

Distributive – an abnormality in the vascular system that produces a maldistribution of the circulatory system; this includes septic and anaphylactic shock.

Distributive – an abnormality in the vascular system that produces a maldistribution of the circulatory system; this includes septic and anaphylactic shock.

Hypovolaemic shock

This is caused by any loss of circulating fluid volume that is not compensated for, as in haemorrhage, but may also occur when there is severe vomiting. The body reacts to the loss of circulating fluid in stages, as described below.

Initial stage

The reduction in fluid or blood decreases the venous return to the heart. The ventricles of the heart are inadequately filled, causing a reduction in stroke volume and cardiac output. As cardiac output and venous return fall, the blood pressure is reduced. The drop in blood pressure decreases the supply of oxygen to the tissues and cell function is affected.

Compensatory stage

The drop in cardiac output produces a response from the sympathetic nervous system through the activation of receptors in the aorta and carotid arteries. Blood is redistributed to the vital organs. Vessels in the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, skin and lungs constrict. This response is seen as the skin becomes pale and cool. Peristalsis slows, urinary output is reduced and exchange of gas in the lungs is impaired as blood flow diminishes. The heart rate increases in an attempt to improve cardiac output and blood pressure. The pupils of the eyes dilate. The sweat glands are stimulated and the skin becomes moist and clammy. Adrenaline (epinephrine) is released from the adrenal medulla and aldosterone from the adrenal cortex. Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) is secreted from the posterior lobe of the pituitary. Their combined effect is to cause vasoconstriction, an increased cardiac output and a decrease in urinary output. Venous return to the heart will increase but, unless the fluid loss is replaced, will not be sustained.

Progressive stage

This stage leads to multisystem failure. Compensatory mechanisms begin to fail, with vital organs lacking adequate perfusion. Volume depletion causes a further fall in blood pressure and cardiac output. The coronary arteries suffer lack of supply. Peripheral circulation is poor, with weak or absent pulses.

Management

The priorities are listed in Box 23.8.

Box 23.8 Priorities in the management of hypovolaemic shock

Shock is a progressive condition and delay in correcting hypovolaemia can ultimately lead to maternal death

If the mother is severely collapsed, she should be turned on to her side and 40% oxygen administered at a rate of 4–6 l per minute

If she is unconscious, an airway should be inserted

Two wide-bore intravenous cannulae should be inserted to enable fluids and drugs to be administered swiftly

Blood should be taken for cross-matching prior to commencing intravenous fluids

A crystalloid solution such as Hartmann’s or Ringer’s lactate is given until the woman’s condition has improved

To maintain intravascular volume, colloids (e.g. Gelofusine, Haemaccel) are recommended

It is important to keep the woman warm, but not overwarmed or warmed too quickly, as this will cause peripheral vasodilatation and result in hypotension

The source of the bleeding needs to be identified and stopped

Septic shock

The most common form of sepsis in childbearing in the UK is reported to be that caused by beta-haemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (Lancefield group A). This is a Gram-positive organism, responding to intravenous antibiotics, specifically those that are penicillin based. In the general population, infections from Gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli, Proteus or Pseudomonas pyocyaneus are predominant; these are common pathogens in the female genital tract.

The placental site is the main point of entry for an infection associated with pregnancy and childbirth. This may occur following prolonged rupture of fetal membranes, obstetric trauma or septic abortion, or in the presence of retained placental tissue. Endotoxins present in the organisms release components that trigger the body’s immune response, culminating in multiple organ failure.

Clinical presentation

The mother may present with a sudden onset of tachycardia, pyrexia, rigors and tachypnoea. She may also exhibit a change in her mental state. Signs of shock, including hypotension, develop as the condition takes hold. Haemorrhage may develop as a result of disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Management

This is based on preventing further deterioration by restoring circulatory volume and eradication of the infection (Box 23.9).

Box 23.9 Management of septic shock

• Replacement of fluid volume will restore perfusion of the vital organs

• Satisfactory oxygenation is also needed

• Rigorous treatment with intravenous antibiotics, after blood cultures have been taken, is necessary to halt the illness

• Retained products of conception can be detected on ultrasound, and these can then be removed