12 Medial canthal pocket syndrome

PRESENTING SIGNS

Medial canthal pocket syndrome (MCPS) is a very common, but rarely diagnosed, conjunctival condition. Typically it presents as a chronic or recurrent conjunctivitis, manifested by a thick mucoid or mucopurulent discharge and moderate conjunctival hyperaemia. Owners complain that the discharge is most noticeable in the morning but can recur later in the day, especially after sleeping, and that it is thick and tenacious. The dog rarely shows any signs of discomfort, despite the ‘red eye’, although occasionally can rub the eyes on waking – presumably to dislodge the discharge. The most frequently presented breeds include the Dobermann, standard poodle, Afghan hound, rough collie and lurchers. Other breeds with broad heads and deep set eyes such as the Weimaraner, golden and Labrador retriever, great Dane and Rottweiler can be affected.

CASE HISTORY

Typically the patient will be a young (6–18 months old), clinically well dog of dolichocephalic conformation. A chronic mucoid or mucopurulent discharge will be reported, centred medially, which does not seem to bother the dog unless it becomes copious. The patient normally improves on topical antibiotic medication, although the discharge is quick to reform as soon as the course of treatment is finished. Often the patient undergoes several treatment periods before careful examination leads to the diagnosis.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

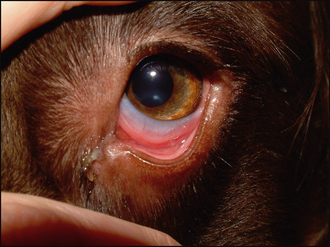

General clinical examination is normal. On ophthalmic examination all neurological tests are normal and the eyes are open and comfortable. Schirmer tear test readings are normal. The most obvious feature is a discharge at the medial canthus and some localized conjunctival hyperaemia (Figure 12.1). The bulbar conjunctiva is normally only very slightly hyperaemic whereas the ventral palpebral and nictitans conjunctiva can appear very inflamed. The discharge is bilateral but not necessarily totally symmetrical. Some discharge is seen within the ventral fornix, in a pocket formed by the gap between the eyeball and the lids (due to the relative enophthalmos inherent in the breed conformation). Follicles can be noted within the conjunctiva close to the discharge on cleaning it away. No corneal pathology is normally encountered but a mild ventral entropion is sometimes seen. Intraocular examination is unremarkable.

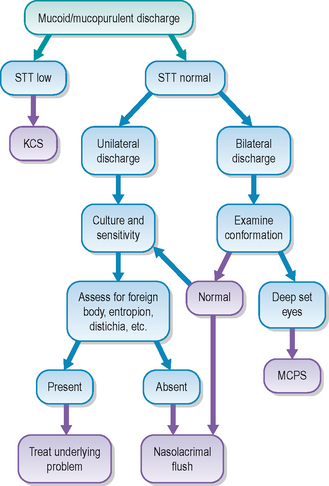

CASE WORK-UP

A thorough ophthalmic examination is essential, and normally this will lead to the diagnosis of MCPS. Careful evaluation of the globe – lid positioning, together with an appreciation of the exact location of the discharge – will help. If the discharge appears purely mucoid in nature then sample collection is not warranted; however, if any purulent component is noted then a swab should be sent for culture and sensitivity testing. Cytology samples are not usually required. It is sensible to flush the nasolacrimal ducts – normally this can be done under topical anaesthesia or light sedation – since a dacryocystitis will be one main differential (although the discharge is likely to be purulent, some discomfort is likely and the distribution is more commonly unilateral than bilateral in the case of dacryocystitis).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Breeds affected with medial canthal pocket syndrome include:

Medial canthal pocket syndrome is caused by anatomical/conformational abnormalities. The common feature of affected breeds is a relatively small globe in a deep set orbit – specific breeding has led to these dogs being slightly enophthalmic. This leads to a gap between the eyeball and the eyelids ventrally – a pocket in the ventral fornix. In addition, mild entropion might be present together with poor tear dynamics. All of this results in a build up of normal ocular secretions at the medial canthus. This is purely mucoid in nature initially, but quickly becomes contaminated by secondary bacterial opportunists. The warm, moist, protected fornix provides an ideal medium for bacterial overgrowth. Thus isolates are normally Gram-positive agents such as Staphylococcus, Bacillus and Corynebacterium spp. Gram-negative bacteria and primary pathogens are rarely isolated. Dust, dirt and general debris can also accumulate in the medial pocket, exacerbating the condition and contributing to the conjunctival hyperaemia and follicle formation. In some young male dogs which are neutered young, the skull never grows to its full maturation. Since broadening of the skull occurs quite late in development, they can be left with a slightly narrower shape which on occasion can exacerbate the tendency for MCPS to develop. The condition is not contagious.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY REFRESHER

Normally the globe should sit snugly in the orbit and the lids glide smoothly over the cornea on blinking. However, pedigree dogs have been bred for a specific appearance over generations and this has led to many conformational abnormalities in numerous breeds. Thus the breeds of dog with a long nose, narrow skull and relatively small eyes, together with those with a broad skull and deep set eyes, are prone to MCPS. The presence of a pocket at the medial canthus – the gap between the cornea and lower eyelid – is abnormal, and allows ocular secretions to build up. The palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva should be adjacent such that there is no gap to allow this accumulation. A relative entropion can develop either medially, functionally reducing nasolacrimal drainage, or laterally, contributing to increased tear production, and both of these alter the local tear dynamics. Failure to naturally remove the accumulated secretions leads to chronic, low grade irritation – manifested by localized conjunctival hyperaemia and follicle formation – together with opportunistic bacterial infection.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

Hygiene is the key to managing this condition. Thus the owners are instructed to bathe the discharge, using sterile saline solution, removing it on a twice daily basis initially. Once under control they should continue with daily cleansing in the morning, plus additional bathing should the dog have been in an environment that could cause irritation – in a dusty area or on the beach for example. Working dogs should have their eyes bathed on returning from the day’s work.

If a purulent discharge is present, then a topical antibiotic agent such as fusidic acid or chloramphenicol should be chosen, pending culture and sensitivity. In general, drops are advised rather than ointments since the latter can contribute to the accumulation of material. However, many cases do not require a topical antibiotic and, as such, several days of regular bathing are advised before opting for antimicrobial treatment. Topical steroids are not normally required. If significant conjunctival follicle formation (lymphoid follicles) has occurred with chronicity these normally resolve following frequent bathing.

Owners should be made aware that the condition is due to the conformation of their pet, and as such can be controlled but not fully cured. Failure to follow the hygiene guidelines will result in repeated bacterial infections, possibly involving eyelid as well as the nasolacrimal system; since these are more serious for the dog, it is important that they are avoided.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

Unless a significant entropion or ectropion is present, surgery is not usually necessary for this condition.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for MCPS is good. Thankfully, corneal involvement is rare and with careful flushing and general ocular hygiene the condition is readily managed. Occasional bacterial infections can occur but these normally respond well to a few days of topical antibiotic drops. Thus, in most cases, it is just a question of owner education and reassurance that is required.

The owner was very frustrated and presented the dog with a history of recurrent conjunctivitis. It was always bilateral, but sometimes one eye was worse than the other. She had treated the dog with a variety of topical antibiotics, both drops and ointments, on numerous occasions, and whilst the dog improved while on treatment, the problem recurred within a few days of cessation. Swabs had been taken for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing and a mixed population of normal commensals, sensitive to all antibiotics tested, had been isolated. The owner was most concerned about the stringy discharge followed by the redness of the eyes. The discharge was always worse in the morning, and sometimes accumulated during the day, especially after he had been asleep. The dog was not at all bothered by his eyes.

CLINICAL SIGNS

General examination was normal. On ophthalmic examination a mild mucoid ocular discharge was present bilaterally. This was centred at the medial canthus. The leading edges of both third eyelids were non-pigmented. Mild conjunctival hyperaemia was present affecting the ventral palpebral conjunctiva and that over the palpebral surface of the nictitans membrane only (Figure 12.3). Eyelid position was normal. No corneal ulceration was noted and intraocular contents were unremarkable.

WORK-UP

The history and clinical examination were typical for MCPS and so no work-up was undertaken.

TREATMENT

It was explained to the owner that the recurrent conjunctivitis present in her dog was very mild and a result of his conformation. She was reassured that the eyes were not particularly red – the non-pigmented third eyelid is a normal variation and she was shown that the colour was the same as the dog’s gums – bright pink but not really inflamed. Once she understood that the discharge was purely a build up of what is normally produced, but that it was not draining normally because of the presence of the medial canthal pocket, she was happy to clean and bathe this twice daily and not to use any further topical medications.

OUTCOME

The outcome was good – only one episode of true bacterial conjunctivitis occurred 3 months later when the dog had been staying with friends who had another dog for a few days, and they did not clean the eyes at all. It was likely that the build up of mucus and change in environment allowed bacterial overgrowth which responded very quickly to chloramphenicol drops. As the dog matured, the amount of discharge present in the morning reduced – presumably as a result of a change in conformation affecting tear dynamics – and the owner only needed to clean the eyes every couple of days.