30 Feline corneal sequestrum

PRESENTING SIGNS

A cat with a corneal sequestrum will be presented with a slightly uncomfortable watery eye. Thus blepharospasm will be present – the cat holds the affected eye partially closed, and the discharge is likely to be serous in nature, although sometimes it can be mucopurulent. It is not uncommon for the discharge to be dark brown in colour – owners may think that the eye has been bleeding due to the colour. The owners might also have noticed a dark discolouration on the cornea, although since this can often be central in position it is not always obvious to them against the dark background of the pupil. The position in the central or subcentral cornea is typical, and the colour can vary from mid amber to very dark brown or black. Any breed of cat can be affected, but Persians of all types and Burmese are over-represented.

CASE HISTORY

The history of previous corneal ulceration is common. Thus the cat could still be under treatment for an ulcer, and on subsequent examination is found to have the typical dark corneal deposition of a sequestrum developing. Slow to heal superficial ulcers are most likely to progress to sequestrum formation. In domestic short haired cats the ulcer is likely to be associated with a traumatic event – a cat scratch for example – while in Persians and Burmese no such history is always present. It is not uncommon for the cat to have had problems with one eye in the past and for similar ulceration and sequestrum formation to recur or to develop in the second eye. Occasionally there will be no history of ulceration and the sequestrum seems to develop spontaneously. In some cats there will be a history of previous upper respiratory disease associated with feline herpes virus (FHV-1). Indeed chronic and recurrent ulcers are frequently associated with FHV-1 infection and secondary sequestrum formation is a well-recognized complication of this.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

General clinical examination is usually unremarkable, unless an active FHV-1 infection is concurrent. Ophthalmic examination will reveal several abnormalities. The affected eye is usually wet, and Schirmer tear test readings will confirm this with a higher reading than in the normal eye. However, on occasion the opposite can be true – a sticky discharge might suggest an associated keratoconjunctivitis sicca so tear test readings should not be overlooked.

Blepharospasm is normally present. Conjunctival hyperaemia and some chemosis are common, as is superficial corneal vascularization. A darkly pigmented patch of cornea defines the sequestrum. This can be raised above the epithelium or subepithelium (the latter is less uncomfortable). The colour can vary from a mid brown to almost black. The ocular discharge is often also darkly stained; however, this is normal for many cats so should not be over-interpreted. Corneal ulceration is often superficial or mid-stromal and fluorescein dye should always be used for any suspected sequestrum. Variable amounts of corneal vascularization can be encountered – in some patients none is noted, while in others there is profuse superficial vascularization and even granulation tissue deposits at the edge of the sequestrum.

In more severe cases the pupil can be miotic, with rubeosis iridis and some aqueous flare – a reflex uveitis – which is most common if bacterial infection is present with the surface disease. In long-standing cases there might be some degree of secondary lateral lower lid entropion with the hairs rubbing on the cornea and exacerbating the problem – this is more frequent in older domestic short haired breeds and is rarely seen in Persians. However, in this latter breed a medial lower lid entropion can be present which may contribute to the problem. In addition, brachycephalic cats can suffer from a relative lagophthalmos such that the central cornea is not fully protected during blinking and tear film dynamics are abnormal (Figure 30.1). This is a serious problem in some of the ‘ultra-type’ Persians with the excessively flat face and bulging eyes – some of these poor cats even sleep with their eyes partially open and corneal health can be severely compromised as a result.

Figure 30.1 Bilateral corneal sequestrum in a Persian. The left eye has the typical central dark discolouration while the right has a superficial corneal ulcer and an amber discolouration to the exposed stroma.

Checking the frequency of blinks, and whether these are complete or partial – where the eyelids do not fully meet – is important. In some patients, particularly the predisposed breeds, both eyes can be affected although often not at the same time, and certainly rarely symmetrically if both are involved.

CASE WORK-UP

If there is any mucopurulent discharge then swabs should be taken for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing. These should be taken before the cornea is stained with fluorescein and are more accurate if the swab is gently rolled at the edge of the lesion rather than sampling the discharge on the face. Samples for FHV-1 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) should be taken if there is a suspicion of a viral component.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Corneal sequestrum is traditionally considered to be unique to the cat, although similar symptoms have been described in the horse. Most cats are young adults, but a wide age range from a few months to 17 years old has been reported. The breed predisposition to Persian types is well recognized and this could suggest an inherited component. Indeed, sometimes related cats are affected.

The presence of some form of corneal insult is thought to contribute to the development of the sequestrum. This can be an obvious incident such as a fight with another cat, but more subtle insults, such as inefficient tear dynamics due to poor eyelid conformation and lagophthalmos, or mild entropion or trichiasis can be involved. The pigment has been shown to be melanin, and probably comes from the tear film, although some corneal sources might also be involved.

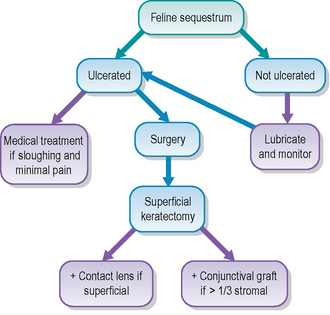

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

If the sequestrum is superficial with no obvious ocular discomfort it can be managed medically since spontaneous sloughing can occur. However, regular re-examinations are necessary to ensure that the lesion is not progressing. Medical treatment with topical lubricants such as carbomer gel are advised one to three times daily, with instructions for the owner to bring the cat back to the surgery should any blepharospasm or significant ocular discharge develop. Topical alpha interferon has been used successfully with a reduction in, or even total disappearance of, the pigment in some cases, but many ophthalmologists have been disappointed by its lack of efficacy!

Owners should be warned that it can take many months for the sequestrum to slough but providing the cat is comfortable it is acceptable to follow this management regimen. Some cats can remain comfortable for years with subepithelial pigment, i.e. the discolouration remains in the anterior stroma and does not involve the actual corneal surface. However, the risk of ulceration and exposure of the necrotic pigmented tissue is always present.

Any cat which shows signs of discomfort associated with the sequestrum should be considered for surgery. It is not advisable to just continue with medical management in these cases since the pain could go on for months, the risk of infection is present and the sequestrum could extend deeply through the corneal stroma such that perforation could occur should the lesion start to slough.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

Surgery for corneal sequestrum involves removing the abnormal tissue via superficial keratectomy. With suitable magnification and instrumentation, and the surgical training to perform such operations, it is possible to undertake this procedure in general practice. However, if any of the above requirements are not present, referral to a suitably qualified and equipped colleague is recommended.

Under general anaesthesia the abnormal cornea, including all pigmented tissue, is excised. Leaving some pigmented material behind can predispose to recurrence. A fixed-depth keratome (surgical knife) of 300 μm is useful, but a rounded Beaver blade (e.g. No. 65) can be used.

If the pigment is quite superficial, less than one-third of the stromal depth for example, then it should heal without requiring a conjunctival graft. Thus it can be left to heal by secondary intention and treated as a superficial ulcer, or a bandage contact lens can be placed to promote ocular comfort during the healing process. Third eyelid flaps can be used for the same purpose, but have the disadvantage of not being able to check on the cornea unless the flap is taken down. Postoperative medication will usually consist of a broad spectrum topical antibiotic drop, with atropine if any reflex uveitis is present. Topical NSAIDs are not usually necessary. Lubricants can also be dispensed.

A conjunctival graft should be used if the pigment extends deeper through the stroma, i.e. more than one-third to half depth. A pedicle graft is most frequently employed, and sutures of 8/0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl, Ethicon) are normally chosen. Since some sequestra can be quite large before they are presented for surgery, and their location is normally central or paracentral, a conjunctival graft can result in some reduction in vision. As an alternative a corneoconjunctival/corneoscleral transposition can be used. This is best left to a specialist but essentially involves moving a clear, partial thickness section of normal cornea from the periphery to the central keratectomy site, with its base still attached to the conjunctiva or sclera. This results in an opaque periphery where the graft is slid across, but the central visual axis is more clear than if a conjunctival graft was used. Postoperative medication is similar to the superficial keratectomy.

If a conjunctival graft has been used it is normal for the pedicle stalk to be trimmed 3–6 weeks post-surgery. However, reports suggest that it is beneficial to leave some blood supply to the grafted tissue as this seems to help prevent the recurrence of the sequestrum. It does mean that the graft will be more vascular and less transparent than if the stalk was fully transected but this is an acceptable compromise if it does provide protection from further problems (Figure 30.2).

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for corneal sequestrum is fair – many cases do require surgery and there is a risk of recurrence, especially in predisposed breeds or if FHV-1 associated. Studies have reported a recurrence rate of 20%. This risk is reduced if a conjunctival graft is used following superficial keratectomy but this has the negative effect of some reduction in central vision and permanent scarring. However, even with large grafts, which would be seriously compromising to a human, the cats seem to show no significant behavioural signs attributable to a reduction in central vision.

Owners should be warned of the risk to the fellow eye, again more of a concern in predisposed breeds compared to domestic breeds where a known traumatic incident predated the ulceration and subsequent sequestrum formation.

CLINICAL SIGNS

The right eye was unremarkable. The left was uncomfortable and a mucopurulent discharge was present. The cornea showed a dark central lesion with a surrounding gelatinous ring of abnormal cornea. Some corneal vascularization was noted (Figure 30.4). Schirmer tear test readings were 15 mm/min in this eye and 12 mm/min in the right. The pupil was slightly miotic.

WORK-UP

The clinical examination confirmed a diagnosis of corneal sequestrum. A swab was taken from the discoloured cornea at the edge of the sequestrum and sent for bacterial culture and sensitivity. Attempts at demonstrating FHV infection were not considered necessary. A profuse growth of staphylococcal spp. was isolated, resistant to chloramphenicol and fusidic acid but sensitive to cefalexin and ofloxacin.

TREATMENT

Under general anaesthesia a superficial keratectomy was performed. This removed all the pigment and surrounding abnormal cornea. A pedicle conjunctival graft was sutured into the defect, actually using two grafts – one with a lateral base and one dorsal to ensure a good blood supply to the large damaged area. Topical ofloxacin (Exocin, Alcon) was dispensed four times daily plus once daily atropine ointment and 5 days of oral cefalexin.

OUTCOME

The cat did very well. After 7 days, treatment continued with just ofloxacin four times daily. Two weeks later treatment was stopped. It was decided to leave the graft to meld into the cornea naturally and not to trim it. Two months after surgery the cornea had cleared well and vision was good (Figure 30.5). The owner was advised not to use the cat for breeding and it was neutered. Two years later a similar sequestrum developed in the right eye – the owner presented the cat quickly. Surgery was again successful.

This case is typical. The owner was a breeder and treated the cat herself prior to bringing it to the surgery. Unfortunately an infection had developed which was not sensitive to the chloramphenicol (or fusidic acid – both of which could have easily been prescribed initially by the veterinary surgeon!). A large graft was required and thankfully this cleared well such that vision was minimally affected. When the second eye developed similar problems the owner brought the cat along straight away such that a much smaller graft was required in this eye.