42 Canine lens luxation

PRESENTING SIGNS

Dogs are presented with a painful eye when suffering from acute anterior lens luxation, the most frequently encountered form in dogs. Normally the owner notices a sudden onset of blepharospasm and increased lacrimation and the eye also appears both red and cloudy. Vision is frequently reduced but owners might not be aware of this if the other eye is normal. Terriers are most commonly affected and young adults, 4–6 years, are most at risk. Affected animals can be depressed and unwilling to eat due to the pain from the condition. Most owners realize that there is something wrong and bring their pet to the surgery quickly, but unfortunately this is not always the case. Breeders will be aware of the condition and as such are more likely to present affected dogs as a matter or urgency.

CASE HISTORY

In most cases there is no previous history of ocular disease, or relevant systemic disease. The dog might have been out playing, such that the owner suspects a traumatic incident, but this is rarely witnessed (and usually has not occurred!). Sometimes the owner will have been aware that the eye was a bit red and watery for a few days before it suddenly became acutely worse.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

On general clinical examination the patient might be subdued and unwilling for the face to be touched – especially on the affected side. Mild pyrexia can be present due to the pain of the condition but otherwise the examination is unremarkable.

Ophthalmic examination is likely to reveal reduced vision on the affected side. A moderate serous ocular discharge might be present, along with blepharospasm and photophobia. It might be difficult to open the eye for examination, especially in moderately enophthalmic breeds such as the miniature English bull terrier. Application of topical anaesthetic drops might assist the examination. Corneal oedema is frequently present, sometimes affecting the whole of the eye (when severe secondary glaucoma has set in) or just in the subcentral area, with a cloudy patch visible. Episcleral congestion will be present. Ulceration is not normally a feature unless the patient has self-traumatized.

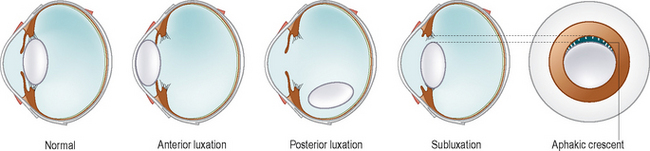

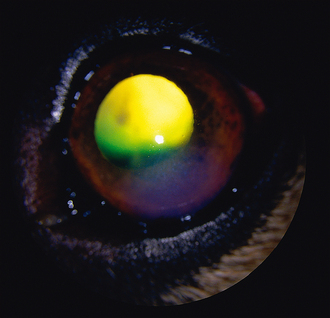

The lens can be visualized in the anterior chamber between the back of the cornea and the front of the iris (Figure 42.1). By viewing the patient from the side it should be possible to see the iris bowing back away from the cornea and the structure of the lens should be apparent. The size of the pupil is variable (if visible!) but is normally mid sized or dilated, and often fixed or poorly responsive to light. If fundus examination is possible it could be normal, or optic disc cupping might be noted (discussed further in the cases on glaucoma). Intraocular pressure measurement should be undertaken if possible, since this will have an important effect on the prognosis and management of the cases.

Figure 42.1 Anterior lens luxation in a 4-year-old Jack Russell terrier. The lens can be seen sitting in the anterior chamber and a subcentral patch of corneal oedema is present where the lens is resting against the corneal endothelium.

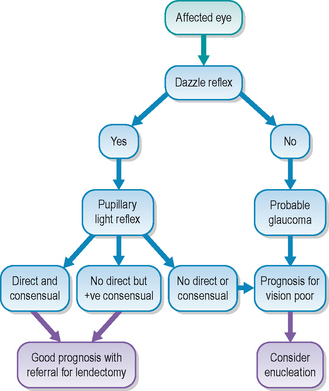

Positive diagnostic tests which can be performed in practice are simple – if there is a positive dazzle reflex in the affected eye, and a consensual pupillary light response in the unaffected eye, i.e. on shining a light into the affected eye the fellow pupil constricts, these both indicate that vision might be preserved with rapid referral for lendectomy. If neither test is positive, then the prognosis for vision is very poor, and any emergency surgery is only likely to salvage the globe.

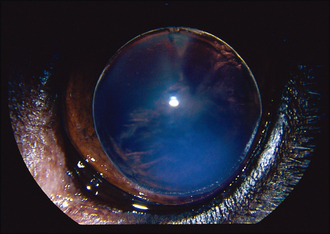

The fellow eye should be very carefully evaluated since primary lens luxation is a bilateral condition, although it is rare for both lenses to luxate simultaneously. The contralateral lens is frequently subluxated – this can be appreciated as iris wobble (iridodonesis) or lens wobble (phacodonesis) as the eye moves. The anterior chamber might be deep or shallow, depending on where the lens has slipped, and strands of vitreous are frequently visible in the anterior chamber. Pupillary dilation with tropicamide might allow the edge of the lens to be visualized – normally it slips slightly ventrolaterally, and stretched lens zonules can sometimes be noted (Figure 42.2). The worse affected eye (with the full anterior luxation) should not be dilated with tropicamide since this could both exacerbate any glaucoma and allow the lens to fall into the vitreous, making surgical retrieval much more difficult.

Figure 42.2 Subluxated lens in a 5-year-old miniature English bull terrier. An aphakic crescent can be seen dorsomedially with stretched lens zonules just visible in this area. The pupil has been fully dilated to appreciate this lens instability although iridodonesis was present clinically.

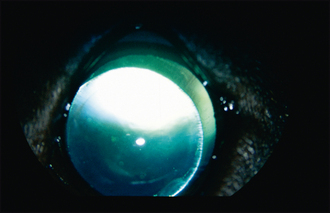

Some patients will not have an anterior but a posterior lens luxation. Typically with these the owner reports the eye was very sore and cloudy, but then became more comfortable, although it still did not look normal. In such cases the subcentral patch of corneal oedema will still be present but the lens is not visible in the anterior chamber (Figure 42.3). The iris normally wobbles (iridodonesis) on globe movement and the anterior chamber is often deep. By looking though the pupil from above, the lens can normally be seen lying in the ventral posterior segment. The different subtypes of lens luxation are shown in Figure 42.4.

Figure 42.3 Posterior lens luxation in an elderly German shepherd dog. There is a patch of corneal oedema but no lens in the anterior chamber or pupil – with careful examination it will be found ventrally in the vitreous.

It should be remembered that chronic glaucoma will cause globe enlargement and can result in lens subluxation or complete luxation. This needs to be differentiated from primary lens luxation. Consideration of the breed, previous ocular history and careful evaluation of the fellow eye should assist.

CASE WORK-UP

Since many cases of primary lens luxation will require referral for emergency surgery, there is little work-up required once the diagnosis has been reached. If the corneal oedema is so severe that intraocular contents cannot be examined, ocular ultrasonography will delineate the abnormal lens position.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Primary lens luxation does have an underlying inherited basis. In the Tibetan terrier it has been shown to be an autosomal recessive form of inheritance, and this is assumed for other breeds as well. Eye testing for prospective breeding animals is recommended for at-risk breeds under the British Veterinary Association/Kennel Club/International Sheep Dog Society (BVA/KC/ISDS) scheme. Similar schemes exist in Europe, USA and Australia. The condition should always be considered in any young adult terrier presenting with an acutely painful eye.

Breeds affected by primary lens luxation include:

The condition is bilateral, and owners must be warned that similar problems are likely in the fellow eye. Indeed it is very common to find abnormalities in the supposedly ‘normal’ eye on examination. The lens zonules are weak and abnormal, and, with time, they fracture, allowing the lens to wobble before it dislocates completely. Unfortunately, the condition is not as straightforward as initially assumed – lens luxation leading to secondary glaucoma. Intraocular pressure (IOP) is frequently elevated before the lens luxates completely, suggesting that there are drainage problems present even when the lens is subluxated. Indeed, careful ophthalmoscopy of the fundus in subluxated cases will frequently reveal optic disc damage associated with high pressures (either pressure spikes or sustained elevations). As such, vision can be reduced well before the lens dislocates completely, meaning that even with early surgical intervention sight is not preserved. The exact mechanisms for this complex problem are not fully understood, but do make the condition very serious for the patient and sometimes frustrating to manage.

Once the lens luxates fully into the anterior chamber a pupil block occurs whereby aqueous cannot flow from the posterior chamber through the pupil and out through the drainage angle. This results in a sudden rise in IOP which causes the acute pain, and can result in permanent blindness. The presence of the lens also directly blocks the drainage angle, and any vitreous which moves forward with the lens further reduces drainage. The lens touches the cornea, and the pressure from it on the corneal endothelium results in local damage to the endothelial pump and a patch of oedema. As the IOP rises, this oedema spreads to include the entire cornea and the whole surface becomes cloudy. If the lens falls into the posterior segment, the pressure will reduce somewhat as the aqueous can flow once more, providing the drainage angle or pupil is not still blocked with vitreous. Repeated episodes of the lens moving anterior then posterior will cause an inflammatory reaction and this can further trigger the secondary glaucoma.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – MEDICAL

Emergency medical management aims to lower the IOP such that permanent damage can be reduced, and to alleviate pain prior to referral for lendectomy.

Posterior lens luxation cases can be managed medically – sometimes successfully for a long time. Treatment here aims to keep the pupil miotic, thus reducing the risk of the lens falling forwards again by providing a solid diaphragm with the iris, and also in maintaining IOP within the normal range. Pilocarpine has been used in the past but has mainly been superseded by prostaglandin analogues such as latanoprost and travoprost. Although expensive, these drugs are effective at maintaining a miotic pupil and increase uveoscleral outflow, thus lowering IOP. The miosis can be profound, such that tunnel vision is all the animal has, but compared to being totally blind (or even enucleated) this is an acceptable compromise. Some patients with subluxated lenses can also benefit from this approach to treatment, particularly if surgery is not wanted.

Any patient on such medication requires frequent re-examination and IOP measurement, and continued liaison with a veterinary ophthalmologist will offer the best long-term prognosis for these patients. If the lens does move anteriorly despite the medication, then surgical removal is required. Some ophthalmologists prefer to remove posteriorly luxated lenses as well as those in the anterior chamber but the risk of complications both during and after surgery is higher with posterior rather than anterior luxations.

TREATMENT OPTIONS – SURGICAL

In general, emergency lendectomy is the only treatment for primary lens luxation if there is any chance of maintaining or regaining vision. This will require referral to a suitably qualified colleague as a matter of urgency. An open sky intracapsular extraction remains the most frequently performed method of lens extraction, but phacoemulsification with vitrectomy is possible in some cases, providing the lens can be stabilized sufficiently to allow the phacoemulsification (which is a less traumatic method of surgery and seems to carry a slightly improved prognosis).

If the eye has been painful for more than 1–2 days it is likely that the secondary glaucoma will have caused excessive damage such that vision has been permanently lost. The absence of a dazzle response in the affected eye and of a consensual pupillary light reflex to the fellow eye are both negative prognostic indicators, and enucleation might be necessary if the IOP is high and the eye irreparably blind. Referral for evaluation of the contralateral eye is still advised in such cases. Some owners will request lendectomy, even knowing that no vision can be restored (particularly to avoid enucleation of the second eye). Frequently patients with lens luxation require life-long medication, hopefully to maintain vision but also to prevent the pain associated with the glaucoma, and owners should be fully aware of the fact that the dog will never be normal.

PROGNOSIS

Primary lens luxation is a horrible disease and the prognosis is guarded in every case. Early diagnosis and rapid removal of the anteriorly luxated lens can maintain vision but topical therapy with anti-glaucoma ± anti-inflammatory medication will be necessary long term. Unfortunately, risks of blinding glaucoma still exist even with early lendectomy. Retinal detachment is the other main complication – as the lens falls forwards and pulls the vitreous with it, this in turn pulls the neurosensory retina away from the retinal pigment epithelium. The resulting retinal detachment is not treatable and results in permanent blindness. Some ophthalmologists perform laser or cryoretinopexy prior to lendectomy in an attempt to ‘spot weld’ the retina in position but the effectiveness of this procedure remains to be established. Dogs with retinal detachment are normally comfortable albeit blind.

Some surgeons will advocate surgery on subluxated lenses but others prefer monitoring since the risk of retinal detachment is present with surgery on these eyes. Many eyes with primary lens luxation end up being enucleated. Frequently owners will accept this with the first eye, but when the second eye becomes affected wish to try all treatment options before resorting to enucleation (or intraocular prosthesis). In general, the prognosis for the second eye is slightly better than for the first, since the diagnosis is made earlier and the owner is more aware of what signs to look for and is usually committed to saving the eye.

With primary lens luxation, prevention is definitely preferred. Owners of affected dogs should inform the breeder in all cases, and the health officer for the breed club as well if possible. Only by avoiding breeding from affected or at-risk animals can we reduce the incidence of this debilitating disease. Genetic testing should be available in the future.