chapter 17 How therapists think: exploring therapists’ reasoning when working with patients who have cognitive and perceptual problems following stroke

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following:

Define clinical reasoning, and identify and define the main forms of clinical reasoning.

Define clinical reasoning, and identify and define the main forms of clinical reasoning.

Describe the differences between a more phenomenological approach versus a more biomedical approach to patient care.

Describe the differences between a more phenomenological approach versus a more biomedical approach to patient care.

Describe how an understanding of clinical reasoning can enhance practice in the area of cognitive and perceptual dysfunction with patients following stroke.

Describe how an understanding of clinical reasoning can enhance practice in the area of cognitive and perceptual dysfunction with patients following stroke.

Provide examples of situations in which a therapist might use procedural, interactive, conditional, and pragmatic reasoning.

Provide examples of situations in which a therapist might use procedural, interactive, conditional, and pragmatic reasoning.

List the five stages in the development of expertise and the key features of each phase.

List the five stages in the development of expertise and the key features of each phase.

Successfully work through the Review Questions at the conclusion of this chapter.

Successfully work through the Review Questions at the conclusion of this chapter.

This chapter reviews how a therapist uses clinical reasoning in the context of practice with patients who have cognitive and perceptual problems following stroke. Because this chapter provides an overview of research literature in the field of clinical reasoning, the content relates to therapists working with all patient groups. However, the case example that illustrates the text is specific to patients with cognitive and perceptual problems following stroke. The chapter examines the different forms of clinical thinking such as scientific versus the phenomenological approaches to patient care and then explores in detail the kinds of reasoning popularly identified in occupational therapy literature, including narrative, procedural, interactive, conditional, and pragmatic reasoning. Influences on clinical reasoning also are explored, such as the therapist’s worldview. Because many academics and therapists agree that the use of case studies that demonstrate expert reasoning provides excellent opportunities for students to develop their own reasoning skills, the reasoning processes of an expert therapist obtained during the author’s research in this field are used to illustrate the text. The final section of the chapter examines how clinical reasoning skills develop as students or new graduates progress over time from novice to expert. Occupational therapists can use this information to make expert clinical reasoning more explicit and therefore easier for students and novice therapists to learn and incorporate in their practice. Throughout the chapter, the term clinical reasoning is used. However, more recently, occupational therapists are adopting the term professional reasoning since clinical reasoning may be associated with a more medically based approach.57

What is clinical reasoning?

Definition of clinical reasoning

Clinical reasoning may be defined as the thinking processes of therapists when undertaking a therapeutic practice. Although occupational therapists have written extensively about clinical reasoning over the past 20 years, they are still just beginning to understand what clinical reasoning is and its importance to practice. Mattingly and Fleming44 described clinical reasoning as a practical know-how that puts theoretical knowledge into practice and a complex (yet often commonsense) way of thinking to find what is best for each patient.

Unsworth66 stated, “To me, clinical reasoning is how I think and make decisions when I’m planning to be with a client, when I’m with a client, and afterwards when I reflect on therapy. It involves intuition, judgment, empathy, and common sense.

. . . how I think about what the client is telling me and what I observe.

. . . what I pay attention to and ignore.

. . . what I respond to immediately or note for future reference.

. . . the way I try to understand my client as a human being.

. . . how I draw on my knowledge of previous clients, their difficulties and successful and unsuccessful solutions.

. . . the way I draw on my theoretical knowledge and apply this in practice.

. . . the stories I share with other therapists about our clients, the therapy we provide and how we feel about it.

. . . the way I consider the total picture including how much therapy time I can spend with the client, financial reimbursement issues, and the support available from the client’s family.

. . . the process of deciding what course of action to take with the client, and how I modify or change this over time.

The way I reason has changed over time, due to greater experience and mentoring from expert occupational therapists and other health professionals. The way I reason in my OT [occupational therapy] practice makes me different from other health professionals.”*

Development of clinical reasoning in occupational therapy

Rogers and Masagatani55 conducted the first empirical study of clinical reasoning in occupational therapy in 1982. The following year, Rogers53 delivered an Eleanor Clarke Slagle lecture that focused on clinical reasoning. This lecture, coupled with a presentation by Donald Schön (an expert in the analysis of professional practice) to the American Occupational Therapy Association Commission on Education, stimulated the American Occupational Therapy Research Foundation to set up the Clinical Reasoning Study. The study was designed by an anthropologist (Mattingly) and several occupational therapists including Fleming, Gillette, and Cohen and was influenced greatly by Schön as the consultant on the project.45 The study ran between 1986 and 1990 and was reported extensively in the special issue on clinical reasoning of the American Journal of Occupational Therapy in November 1991. In 1994, Mattingly and Fleming44 published this work in a book. The content of this chapter draws on the foundation laid by Mattingly and Fleming in the Clinical Reasoning Study and extends these ideas using research and theoretical literature from the past 10 years from Sweden, the United Kingdom, Australia, and North America.

Clinical reasoning and theory

The first consideration is the use of clinical reasoning to explore the practical theories of the profession. One of the aims of the Clinical Reasoning Study was to make explicit the tacit knowledge contained in the practical theories used by the therapists studied. The study argued that this tacit knowledge could be shared if a language to describe therapists’ reasoning could be developed. Hence the study aimed to examine the types of reasoning processes used by therapists to use their many practical theories.

Mattingly and Fleming44 made the distinction between espoused theories and theories-in-use. Espoused theories are those held true by the discipline. These theories are intelligent speculations about the workings of a particular phenomenon, which then usually are tested out and refined through research. Theories-in-use, or practical theories, are those generated by practice. Although many scientists do not support the notion that theory can arise from practice, researchers such as Mattingly and Fleming44 and Schön61 believe this is possible. Many of these practical theories pass verbally among therapists when working together, and they often guide therapists in their day-to-day practice. Theories-in-use generally are accompanied by a large fund of tacit knowledge. Often therapists cannot describe what they are doing or why; their expert knowledge is tacit. While this knowledge remains undocumented, it cannot be used to contribute to the fund of knowledge for the profession. Hence a language to describe how and why therapists use certain techniques or communicate in particular ways is needed.

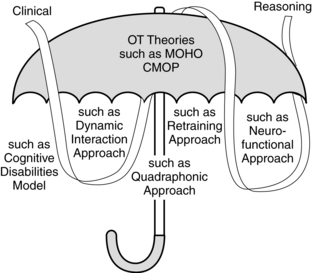

In addition to the way clinical reasoning can be used to explore the practical theories of the profession, one also must consider that the construct of clinical reasoning is itself developing into a theory. Knowledge of clinical reasoning has been growing steadily over the past 20 years and is evolving slowly into a theory derived from practice. If clinical reasoning surfaces into a theory, what is the relationship between this and other theories or frameworks that guide occupational therapy practice? Kielhofner35 described conceptual practice models as bodies of knowledge developed in occupational therapy for its practice. However, whereas some models can be applied to many patient groups, some are more targeted for patients with particular problems. Hence, Stanton, Thompson-Franson, and Kramer63 described some conceptual practice models as generic and others as specific to the patients’ problem areas. To think about these generic models as umbrella models, such as the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance11,38 or the Model of Human Occupation,34 is useful. In the field of cognitive and perceptual dysfunction, an umbrella conceptual practice model is used with a specific practice model such as the Cognitive Disabilities Model,2 the dynamic interaction approach,32 the quadraphonic approach,1 the retraining approach,32 the neurofunctional approach,26 or the compensatory or rehabilitation approach.21,74 The evolving theory of clinical reasoning seems to interface smoothly with all of these conceptual practice models. A clinical reasoning approach cannot replace any model, and yet such an approach can be used to complement these models and add a different perspective to clinical work. Using a clinical reasoning approach with an umbrella and specific practice model ensures that the therapist acknowledges and can describe scientific and phenomenological approaches to patient care (as are described next) and has a language to describe the kinds of thinking that guides practice, including why one chooses a particular practice model. Fig. 17-1 depicts this relationship between a generic occupational therapy (umbrella) conceptual practice model, specific conceptual practice models, and clinical reasoning.

Clinical reasoning with patients who have cognitive and perceptual problems following stroke

At some point in their careers most occupational therapists work with patients who have cognitive and perceptual problems. One of the largest groups of patients with such problems is the group of stroke survivors. The American Heart Association4 estimates that each year approximately 795,000 Americans will have a stroke. Documented evidence indicates that at any one time over three million persons in the United States have a stroke-related disability that requires ongoing management and care.4 Global estimates of incidence of cognitive and perceptual problems following stroke vary enormously because of differences in assessments used, populations studied, and time since stroke onset. However, Kong, Chua, and Tow36 estimate that approximately 41.5% of persons who experience stroke and are more than 75-years-old experience some deficit in this area. Closer examination of specific impairments shows that up to two thirds of individuals with acute right-hemisphere stroke demonstrate signs of unilateral neglect50 and that 23% of patients have more lasting experience of this problem.51 The incidence of apraxia is reported to be lower, with estimates of approximately 30% of patients with left hemisphere damage experiencing problems.17 When occupational therapists work with patients after stroke, the language of clinical reasoning can aid them in describing their practical and espoused theories (and how these translate into day-to-day therapy) to colleagues, students, and the patient and patient’s family. Descriptions of the key types of reasoning that form this language are described in the next section.

The conceptual practice model that the therapist adopts guides the kinds of evaluations and interventions that the therapist will undertake,66,71 and the section on Procedural Reasoning describes this in more detail. For example, a therapist who uses a remedial or bottom-up approach such as the retraining approach32 assumes that remediation of function is possible, and this fundamental belief helps shape all the reasoning that follows. Such therapists believe that reorganization of brain activity is possible following stroke. Reorganization refers to the ability of the central nervous system to reconfigure and adapt itself in various biological and functional ways to perform an activity. In contrast, a therapist who uses an adaptive, or top-down, framework such as the compensatory or rehabilitation approach21,74 to patient care believes that the therapist needs to work with patients in the everyday occupations the patients want and need to do and that the environment can be modified or that compensatory strategies can be used to assist patients to complete tasks. The therapist starts at the top, which is the desired occupation rather than working with the patient on the underlying performance components. When using a top-down approach, the therapist does not assume generalization of compensation strategies taught from one activity to another.66

Theoretical information provides only the starting point for therapy. Many writers suggest that only through clinical practice can clinical practice develop and creative solutions be found for problems that are not mentioned in texts.12,60 When problems or obstacles arise in therapy, occupational therapists need to be able to reason to reach a solution. For example, theoretically, therapists know to assess the patient’s sensation to exclude these problems before the assessment of complex perceptual problems. But what if the patient has insufficient or unreliable language, making sensory testing impossible? What if the patient is depressed and refuses to undergo sensory testing? Only through learning about clinical reasoning and developing a language to help therapists reason through these problems and seek answers with colleagues can practice develop.

Case study: sally and sam

The next section deals specifically with the different types of clinical reasoning therapists use. To illustrate these different types of thinking, clinical reasoning examples from Sally are provided. Sally is an expert occupational therapist working with a 28-year-old male patient, Sam, who experienced cognitive and perceptual problems along with motor weakness on his right side following a left-sided anterior communicating artery stroke. Sally is the senior therapist in a team of eight therapists at a rehabilitation facility with 60 beds. She manages a caseload of patients with neurological problems following stroke, head injury, or disease processes such as Parkinson. The examples of Sally’s reasoning are based on research transcripts in which Sally retrospectively described her therapy sessions with Sam.68 Three transcripts were recorded, one following an initial outpatient evaluation session with Sam, another following a typical treatment session, and a third when Sam was being discharged from regular outpatient services. Hence transcript excerpts are headed with Evaluation, Intervention, or Discharge Session. These transcripts have been modified (and pseudonyms used) to protect the identity of the patient and therapist or more clearly to illustrate a particular form of reasoning. Sally’s description of Sam together with details of his impairments, therapy goals, and the occupational issues he faces are outlined in the following section, which examines the difference between chart talk and narrative reasoning.

A language to describe the types of clinical reasoning

This section explores the different types or modes of clinical reasoning. Although several different types of reasoning are described, these types fit into a more biomedical or a more phenomenological approach to patient care. As described by Mattingly,41 the profession of occupational therapy deals in two practice spheres, the biomedical sphere that focuses on the mechanical body and the social, cultural, and psychological sphere that concerns the meaning of the illness to the person. Hence, Mattingly referred to occupational therapy as the two-body practice. Usually, these more scientific versus more phenomenological approaches to patient care coexist uneasily. However, Mattingly noted that many occupational therapists seem to be able to shift rapidly and easily between thinking about the patient’s disease processes (body as a machine or the physical body) and the patient’s illness experience (the lived body). Mattingly described how some therapists can integrate these two approaches so seamlessly that “biomechanical means may be used to achieve phenomenological ends or the reverse.” The synthesis of these two perspectives into what is called best practice in occupational therapy also reflects the paradigm shifts the professions has undergone over the past 40 years.

Therapists require different types of reasoning when working in these two different spheres and need different ways of communicating this reasoning. When occupational therapists are talking about the patient’s medical problem, they are more likely to use a kind of language that Mattingly and Fleming44 described as chart talk. In contrast, when the therapist thinks about the patient as a person who also has a medical problem, the therapist is more likely to reason in what Mattingly and Fleming described as the narrative form. Mattingly42 described occupational therapy clinical reasoning as being “largely tacit, highly imagistic, and deeply phenomenological mode of thinking.” Mattingly therefore suggested that narrative reasoning is the best basis for most clinical reasoning in occupational therapy. Narrative reasoning means that stories are told or created to assist the therapist to make sense of what is happening with the patient. When thinking about the patient as a person, his or her illness experience, and what therapy will mean for the patient’s present life and future, therapists commonly think and talk in the narrative form. These two ways of communicating clinical reasoning are described next.

Narrative reasoning and chart talk

Therapists use narratives or stories to convey their thinking to other professionals, students and novice therapists, and patients. Viewed in this light, narrative reasoning is a way of reporting or giving words to the other forms of clinical reasoning, which are discussed later in this section.64 Narrative reasoning is also a form of phenomenological understanding. Narratives can take the form of storytelling or story creation. Storytelling can reveal how the therapist treats and interacts with the patient and can be used to explain how the therapist perceives the patient to be managing the disability. Storytelling is most predominant when therapists are carrying out the day-to-day procedures of evaluating and treating patients, trying to understand the patient as a person, and what is happening in therapy.3 Story creation, however, involves creating a picture of the future with the patient that includes setting goals to work toward in therapy. Story creation is more common when therapists envision a future for the patient, or engage in conditional reasoning (described in detail later). However, the story created for therapy usually does not proceed without the need for revision, and experienced therapists are adept in changing the therapeutic story midstream.40 In the following example, Sally tells the story of Sam to the researcher. The emphasis of this narrative is on Sam as a person rather than the medical aspects of Sam’s stroke.

Evaluation session, part 1.

“Basically the idea behind this initial outpatient session is just looking at basic home independence for Sam. He was discharged home a couple of days ago, so he is back here every day at the moment as an outpatient. It was actually a self-discharge. We were heading toward that anyway, and the plan was for Sam to live in a bungalow or trailer on his family’s property. He used to live in a trailer at the back of their property, but this has rotted out and they’ve pulled it down. They [his family] actually have a very small house, and it’s just not really appropriate for him to be living there since he has teenage stepsiblings, and he is a very independent young man; he wants to have his own space, which you can really understand for a young man, so the idea for him is either to get a bungalow at the back of his family property again or go to a community-based group home. However, that hasn’t worked out yet, and so Sam is in the family home for the moment. Sam had his stroke six weeks ago. He was in intensive care for three days, indicating the severity of the infarct, which was in the left anterior communicating artery. The CT [computerized tomography] scan revealed a reasonably large lesion area, and, consistent with his lesion, Sam experiences difficulties with walking, and he is using a 3-point stick. He also has reduced movement in his right arm, and particularly, he has difficulty using his hand since the movements are slowed and his grasp is reduced. He’s also got some moderately severe cognitive problems.

“Sam, prior to his stroke, was unemployed, was a drug user, and didn’t have a lot that interested him in his life other than playing the guitar, so in terms of finding activities that are meaningful for him, it’s been quite hard, and we spent some really worthwhile time in therapy using the Interest Checklist and found that cooking is one activity he loves. He is really motivated; he is a terrific guy; he’s really cooperative and tries really hard and seems to always understand the rationale, even though I always explain to him why we are doing what we are doing. So I suppose the two reasons why we chose this cooking activity for today are one, looking toward him in the long-term developing a repertoire of basic meals he can prepare in his own place, and also because it specifically works on improving his planning and problem-solving skills, attention, and his standing tolerance.”

In contrast to narrative, reasoning is the kind of language therapists use when speaking with colleagues about a patient’s biomedical problems. Although the foregoing example is largely in the narrative form, Sally does slip into another kind or more factual description when she talks about Sam’s medical problems. Mattingly and Fleming44 reported that when therapists discussed procedural aspects of the patient’s physical condition, shared treatment goals, and planned evaluations and interventions, they were more likely to use chart talk and scientific forms of reasoning. During these discussions, therapists tended to use a biomechanical way of understanding the patient’s problems. For example, in the following excerpt, Sally discusses aspects of Sam’s splinting regimen using chart talk.

Intervention session, part 1.

“A lot of the focus with Sam in the past few weeks has been on him getting functional use of his right hand, which is his dominant hand. He’s actually got quite increased muscle tone as you can see there. He has a night splinting regimen, and going back a few weeks ago, he basically forgot he had a right hand; he just wasn’t initiating using it, and he quickly taught himself to be left dominant. So we’re really pleased with the progress he’s making in extending his wrist and MCP [metacarpophalangeal] and PIP [proximal interphalangeal] finger joints. We are talking about his splint at the moment because I did quite a radical change to the splint last Friday, and I was asking him if it was giving him any pain because it does give him a little bit of pain as we have been gradually increasing the extension of his wrist and of his fingers. He told me he took it off midway through the first night, but that he has been able to wear it through the last couple of nights.”

Although therapists usually write case notes in the brief and factual language of chart talk, chart talk and narrative reasoning possibly may be interwoven when therapists describe the patient. This idea was suggested previously when noting that occupational therapists seem to be able to weave between a biomedical and phenomenological understanding of the patient. In the first transcripts from Sally, one can see how she slips between discussing Sam as a person and describing the facts of his stroke. Research evidence also supports that therapists interweave these forms of reasoning when discussing and describing their patients.67,69-70

The therapist with the three-track mind

Mattingly and Fleming44 suggested that when describing the patient’s biomedical problems, therapists tended to use chart talk. The kind of reasoning that supports this sphere of patient care draws on scientific reasoning. More specifically, Fleming23 referred to this kind of thinking in occupational therapy as procedural reasoning. When reasoning in the narrative form and considering the meaning of the illness for the patient (when using a phenomenological perspective to patient care), occupational therapists use two other types of reasoning, which Fleming labeled interactive and conditional reasoning.

Fleming23 also suggested that therapists seem to be able to think in these reasoning tracks simultaneously. Hence the phrase, “the therapist with the three-track mind” was coined. Therapists seem to monitor the procedural aspects of the treatment, such as the evaluations and interventions to be used with the patient and how the patient is performing, while being able to elicit the patient’s cooperation and understand the person’s response to the treatment using interactive reasoning.22 Therapists also seem to engage in considering the patient’s condition and how it could alter over time and to imagine how the patient’s past, present, and future could be facilitated by occupational therapy intervention. Fleming and Mattingly25 argued that experienced therapists were able to use these forms of reasoning in rapid succession or use different forms almost simultaneously. Fleming22 suggested that “Reasoning styles changed as the therapist’s attention was drawn from the clinical condition to another feature of the problem, and to how the person feels about the problem, almost simultaneously, using different thinking styles; and they did not ‘lose track of’ their thoughts about aspects of a problem as those components were temporarily shifted to be the background while another aspect was brought into the foreground.”

Although Mattingly and Fleming44 identified these three modes of reasoning together with narrative reasoning, subsequent theoretical and empirical publications have suggested that these might not be the only forms of reasoning used. In fact, occupational therapists and other allied health scientists have now documented multiple types of clinical reasoning including scientific, diagnostic, pragmatic, management, collaborative, predictive, ethical, intuitive, propositional, and patient-centered.30,39,54,56 In this chapter, only the most commonly described forms of reasoning are presented, together with comments on their interrelationship. Hence, this chapter explores narrative, scientific, procedural, interactive, conditional, pragmatic reasoning, and a newly identified form of reasoning termed generalization reasoning.

Procedural reasoning.

Therapists use procedural reasoning when thinking about the patient’s problems and the kinds of evaluation, intervention, and outcome measurement procedures to use. Whereas interactive and conditional reasoning are based more in the phenomenological sphere and therefore are narrative forms of reasoning, procedural reasoning is based more in the biomedical sphere and therefore draws on scientific reasoning. Scientific reasoning almost exclusively forms the basis for medical reasoning and decision-making. Scientific reasoning is the process of hypothesis generation and testing that generally is referred to as hypothetico-deductive reasoning. This form of reasoning most often is used to make a diagnosis of the patient’s medical condition. Although occupational therapists are more concerned with identifying the patient’s occupational problems rather than the medical diagnosis, therapists do draw on the ideas of scientific reasoning when reasoning procedurally.

In the medical decision-making literature, terms such as diagnosis, prognosis and prescription, cue identification, hypothesis generation, cue interpretation, and hypothesis evaluation are used commonly.20 However, in the occupational therapy literature, terms such as problem identification and goal setting are more common. When determining what the patient’s problems might be and selecting appropriate interventions, Fleming22 identified that therapists were involved in a variety of procedural reasoning strategies and methods of thinking. These methods of thinking include the four-stage model of problem-solving, which is based on the hypothetico-deductive reasoning, goal-oriented problem-solving, task environment, and pattern recognition of the medical model. Each of these methods of thinking is described briefly.

Procedural reasoning generally begins with problem identification, and Elstein, Shulman, and Sprafka20 developed a four-stage model of problem-solving that focuses on problem identification. Fleming suggests that therapists may use this model when determining the patient’s occupational problems.

The four stages in this model are as follows:

1. Cue acquisition: The therapist gathers cues or pieces of information about the patient and the patient’s difficulties.

2. Hypothesis generation: The therapist generates several plausible explanations for the observed cues.

3. Cue interpretation: The therapist compares each hypothesis with the cue set and selects the most logical or best hypotheses to explain the cues.

4. Hypothesis evaluation: Finally, the therapist asks what the best hypothesis is by evaluating which cues generally are thought to be necessary for selecting each hypothesis and for the presence of critical cues for selecting each hypothesis. In this way, one hypothesis should be identified as the best.

All problem-solving in occupational therapy is goal directed so that therapists and patients work together to ensure the patient can participate in desired and needed occupations. Although therapy is conducted mostly in clinical environments, therapists think constantly about translating what is being accomplished into the patient’s home environments. Hence procedural reasoning also is concerned with considering the environment in which the task is conducted. Pattern recognition refers to a therapist’s ability to identify the kinds of patient cues and features that occur together. For example, a therapist who observes a patient go several times to get the necessary toiletries for the morning bathroom routine may question whether the patient has a planning and organization problem or difficulties with memory. However, adding this information to many other observations of difficulties with planning, judgment, and problem-solving prompts the therapist to consider difficulties with executive functions. The ability to recognize patterns of cues and behaviors becomes part of the therapist’s tacit knowledge.22 The therapist recognizes these patterns without needing actually to think through or articulate the emerging trend. Finally, current practice culture is driven by providing evidence to support the evaluations and interventions therapists select to use with patients. Therefore, an occupational therapist reasons procedurally when asking, “What evidence is there to support the treatments I offer?”

In the following example that illustrates procedural reasoning, Sally describes setting up a cooking task with Sam.

Intervention session, part 2

Interviewer: I notice you just set up the fry pan, so tell me about that.

Sally: Yes. I basically set it up due to the timeframe for this session and the demands on Sam. We’ve been gradually upgrading the task demands on Sam, but today I said to Sam that I would set the fry pan up and also because reaching that would be extremely hard for him. He would have to lean right over the table, and also I was planning to put the rice on to cook, just to let him focus on the one task today.

Interviewer: So, you would do the rice, and he would do the stir-fry vegetables in the pan?

Sally: Yes and that’s sort of been from past experience because when he has to attend to two things, he will forget one of them, like the rice. So once we sort of feel that he’s managing cooking one dish well, then we’ll upgrade it and include the second dish, the rice, and we would probably have something like a prompt sign on the table for him to remind him to check the rice and also the timer, which we always use.

In the example of procedural reasoning, Sally talks about some of the difficulties that Sam has with the cooking task because of his memory and planning difficulties. However, more that just looking at Sam’s problems, in this transcript excerpt, Sally goes on to incorporate into the activity her understanding of how Sam learns. This kind of reasoning is referred to as interactive reasoning and is described in the next section.

Intervention session, part 3

Sally: I think with Sam, he’s the sort of guy that learns from repetition. So, by letting him go in and make mistakes—you will see later, he comes back to the table and I’ve actually let him come back without the can opener and all those things—so that’s a way for him to stop and think what he needs.

Interactive reasoning

Therapists use interactive reasoning to consider the best approach to communicate with the patient and to understand the patient as a person. In the Clinical Reasoning Study, Mattingly and Fleming44 found that although therapists reported their procedural practices, they did not report their interactions with the patient. Hence, the authors referred to interactive reasoning as the underground practice. Therapists often see patients at difficult times in their lives; their health or well-being is challenged, and they may be experiencing their body in a new way. This can be frightening for the patient, who may respond with confusion or anger. The skilled therapist needs the ability to communicate effectively with the patient so as to share information about the patient’s progress and prognosis, and the therapist can gain an understanding of how the patient perceives the disability and views the future.44 However, because many patients who experience stroke also have a clinical lack of insight to their problems, the therapist faces the additional difficulty of collaborating with patients who may not have any understanding of their problems. Therapists need to take extra care with these patients to establish meaningful and realistic goals.

In its most simple form, interactive reasoning is concerned with how the therapist communicates with the patient. In the following example, Sally reasons about the way she interacts with Sam to make sure he can follow through with what she wants him to do.

Evaluation session, part 2

“I’m just sort of basically explaining to Sam the actual movement I want him to do. Often, if I can, I try to decrease the verbal cues and actually look at giving some physical cues as well. That carries right over to all of his program. So, for example, when we do personal care, I really have to use a combination of both physical cues and verbal prompting. I’m certainly trying to decrease that. I think with Sam and a lot of patients with stroke or brain injuries, it just takes much longer for them to respond. It just doesn’t go in as quickly as it does with us. My strategy with Sam at the moment is give him the instruction or prompt him and then give him some time to respond, and then go on to give him some physical guidance as well.”

More than just basic communication, interactive reasoning is also about understanding the patient as a person who has interests, needs, values, and problems, so that the therapist can understand the disability from the patient’s perspective. Interactive reasoning stems from the way therapists value the patient as an individual and the therapist’s deeply held humanistic beliefs. In the following example, Sally indicates that she understands Sam as an easygoing person who might want to take the easy way, even though he often can achieve more than he thinks.

Intervention session, part 4

Sally: That’s another one of the jokes we have. He’s been asking me for months about having elastic shoelaces, and I just said, “No way, you’re not having elastic shoelaces. You don’t need them.”

Interviewer: How does he know about them?

Sally: I don’t know. He just came out of the blue one day, and I said, “Who told you about those?” And he is the kind of guy that will say to you, “Anything to make my life easier, I will do.” He will say, “I’m a bit slack,” and that’s his personality. I was having a joke with him before saying, “At least I believed in you,” because now he’s doing his shoelaces independently. I just said to him, “Imagine if we got you elastic shoelaces. You would look a bit silly out there with these big elastic shoelaces.” So joking around with him has worked really well.

In this example, Sally talks about joking around with Sam as a way of building a shared language between them and gaining his cooperation in therapy. In the following example, Sally elaborates further on this use of humor in therapy.

Intervention session, part 5.

“Yes, and I use humor as well. That’s the approach I often take with people but especially with people like Sam, who are really laid back and low key; that really works well. Sam responds much better to a friendship sort of approach, just encouragement, rather than the dictator sort of approach. That’s not something Sam goes for. In fact, he bumps up against that approach, and I think that’s been a pattern throughout his life. . . . With Sam in particular, like I said, sort of having our own private joke, like I say, “I’m the hand police,” and so if I see him not using his hand, I only have to say “hand police,” and we can have a bit of a laugh. And we can also laugh a bit at some of the failures he’s had, and you obviously have to pick the people you do that with. You wouldn’t do that with someone who has got poor insight, but Sam has excellent insight. But, like I said, that’s my approach with a lot of people, but with other people you just don’t use it because it’s not appropriate, and they get very upset if you sort of stir them up a little bit, but with Sam, no, he’s not problem at all.”

Using a variety of authors’ works, Mattingly and Fleming44 put together a list of purposes for which interactive reasoning is used:

1. Engage the patient in therapy.43

2. Know the patient as a person.13

3. Understand the patient’s disability from the patient’s point of view.43

4. Individualize the therapy for the patient to match the treatment goals with the person, disability, and experience of the disability.24

5. Convey a sense of acceptance/trust/hope to the patient.37

6. Break tension through humor.62

7. Build a shared language of actions and meanings.15

8. Monitor how the treatment session goes24 and demonstrate interest in the patient and the patient’s concerns without indicating disapproval or distaste of the condition.10

Hence, interactive reasoning is concerned with collaborating with the patient as a partner in the therapy process. Together the therapist and patient must devise goals that are meaningful to the patient and that also serve to promote the patient’s occupational functioning. Humor seems to be one way to facilitate patients to collaborate in the therapy process, and Mattingly and Fleming44 discussed several other strategies that therapists use to engage patients in this collaboration. These strategies include the following:

“1. Creating choices. Therapists try to engage clients in therapy by providing choices in relation to problem areas the client wants to work on, and the specific occupations or activities they might use in therapy.

“2. Individualizing treatment. A therapy program that is uniquely tailored for the client, through both the ingenuity of the therapist and the involvement of the client, generally keeps the client engaged in therapy. While the goals of therapy for a client with a memory problem may be quite similar, the way the therapy program is structured, and the activities that the client and therapist choose are usually different for each client.

“3. Structuring success. Therapists often structure, or manipulate therapy to provide the client with opportunities for success, and thus promote their alliance. Therapists are often in the business of revealing problems, and then working with the client to reduce their impact. Unless the client has some successes along the way, it is very hard to keep the client motivated, or to maintain a positive relationship with the client. Therapists often talk about keeping the client optimally challenged. This includes pushing the client to achieve, but not so far that he fails. This has been described as the ‘just right challenge.’[9,16]

“4. Joint problem solving. Another approach therapists use to facilitate client engagement in therapy is to ask the client to help them in the problem solving process. For example, if the therapist has difficulty in using a piece of equipment, or in devising a strategy for a transfer, calling on the client for his input enables him to take a strong and active role in therapy if only for a short time.

“5. Gift exchange. The final two strategies that Mattingly and Fleming[44] found [that] therapists use to build an alliance with their clients were more personal in nature. The researchers found that therapists would go out of their way, or their formal roles to do something nice for the client such as bake a cake for a client’s birthday. In this way the therapist shows a willingness to care for the client in a more personal way. In exchange, clients often feel more committed to co-operate in therapy. Clients may also give gifts to the therapist. These may be as simple as a flower, a few words of thanks or a hug, all of which demonstrate their personal thanks for the therapists’ involvement in their treatment.

“6. Exchanging personal stories. Exchanging personal experiences is another powerful way to develop a bond with a client. Mattingly and Fleming[44] found this was commonly used by clinicians to engage the clients in therapy, and that clinicians were usually aware of the value of this strategy.”*

Sally talks about the importance of patients choosing their own therapy activity. This illustrates the point made before about creating choices for the patient and supports the idea of a patient-centered practice.

Intervention session, part 6.

“Now we’re upgrading his program, and we have a hand function group that Sam will start coming to. In this group we are looking at a lot of active wrist and finger extension because that’s what he really needs to work on, and a lot of gross grasp because he really has trouble extending his third, fourth, and fifth fingers at this stage. Even in the hand function group, although I don’t actually run it, two of the other OTs [occupational therapists] do; it’s actually fantastic, and the therapists find out what it is the person who wants to do. We have had people in the group eating using chopsticks in their other hand or practicing putting CDs in and out of their player. We really try and keep people motivated by choosing their own therapy activities, and it’s a really great fun group that people get a lot out of, I think, more than doing therapy on a one-to-one basis. A lot of my patients, from my experience working here, if they can’t see or understand why they are doing a stupid exercise, you just lose them. As I said, we really try to emphasize here that patients choose meaningful activities.”

Finally, the following transcript excerpt shows an example of how Sally structures the therapy session to ensure that Sam has some success. The motivating effect of this success pushes patients forward in their therapy programs.

Evaluation session, part 3.

“We’ve just finished making toasted cheese sandwiches with Sam, and he did so well. And I made sure that Sam could do nearly all of this activity, since I’m challenging him with the stir-fried vegetables, so its good to balance this a bit with a cooking task that he can complete successfully. I was telling him how well his right hand is working now, and he was like so many other patients who say. ‘Gosh, couldn’t I use my hand at the start?’ and we’ll say, ‘No,’ and they’ll just be amazed, so yes, having this success in an activity just keeps them going, I think.”

Conditional reasoning.

Conditional reasoning was the last mode identified in the Clinical Reasoning Study. In describing the emergence of this mode, Fleming22 wrote, “Later we realized that there was a third type of reasoning that therapists employed when they thought of the whole problem within the context of the person’s past, present, and future; and within personal, social and cultural contexts. This was an especially useful form of reasoning, which therapists used when they wanted to, as they say, ‘individualize’ the treatment for the particular person. We called this ‘conditional reasoning’ because it took the whole condition into account.”

Conditional reasoning takes the whole of the patient’s condition into account as the therapist considers the patient’s temporal contexts (past, present, and future), and his personal, cultural, and social contexts. Fleming22 proposed that this form of reasoning is based in the cultural and social processes of understanding one’s self and others and is used when the therapist wishes to understand the patient from a phenomenological perspective. A therapist uses this form of reasoning in trying to understand what is meaningful to patients in their world by imagining what their life was like before the illness or disability, what it is like now, and what it could be like in the future. In the following transcript excerpt, Sally thinks through the issues surrounding Sam’s life at home and what the future holds. This example not only illustrates conditional reasoning (e.g., discussing how Sam’s condition has changed and on what his residential care situation is conditioned) but also shows aspects of what some authors describe as ethical reasoning,5 where Sally imagines how Sam might behave in different residential settings and how his drug use may affect other residents.

Discharge session, part 1.

“Now, we’re talking about a big issue for Sam at the moment; it’s the breakdown of his residential situation at home. He’s still in his parents’ house, but he can’t stay there much longer, and they want him out. It’s really hard because a lot of the residential settings [supervised housing such as nursing homes] are too low level for him, or the ones that he could live in and have day-to-day contact with someone in attending care support, there’s no vacancies or he doesn’t like them, and the other issue with him is if he goes into a group home, other people are at risk. He actually, unfortunately, shares his drugs around, and most of these houses have young men with brain injuries, and so we have a responsibility to ensure, you know—they can’t obviously make an informed decision about whether to take the drugs Sam offers them. With Sam it’s a premorbid thing, and essentially we have come to the realization he is not going to change. He’s tried drug counseling, then we had a consultant, then social workers have tried, his mum has tried, and she is tearing her hair out, but he just—it’s something he likes to do no matter what we say. He acknowledges there is a high risk of psychotic incidences and all these things, but he just doesn’t really budge from that. You know, when it comes down to the crunch, he just can’t resist the temptation.

“So, essentially the two things we are trying to do at the moment is one, structure all of his time, since its when he’s bored that he starts smoking drugs and things. Secondly, looking into attendant care so that he has someone helping him to live in a shared house, because if we look at him coming to our transitional living house, which is just across the road here, and I was also, at the end of the session, discussing with him the increased responsibilities that would be on him, and he is a very capable young man. He can make basic meals for himself now. Like, you didn’t see him walk in, but he is now mobile with a stick, which he is hardly using. He has really well exceeded all of our expectations for someone with such a serious stroke. He still has ongoing cognitive impairments with things like memory and problem-solving and planning, but with repetition and things, he can really learn to do things himself. It’s really hard at the moment until we find out whether there’s a bed available in one of the nearby group share houses. He is quite keen about that idea, but still his favored option is for himself to get a trailer or a bungalow on his family block.”

Fleming22 described the third form of reasoning as the most elusive. Conditional reasoning is not always conscious and therefore is more difficult to get at, understand, and describe. Conditional reasoning requires more than a simple knowledge of the patient’s condition; it also calls for an understanding of how the condition has affected the individual’s work, social situation and leisure, and view of self. Fleming22 reported that therapists who were more interested in patients’ medical conditions or occupational therapy treatment procedures than the patients themselves did not seem to use conditional reasoning. This is often the case with less experienced therapists who are still grappling with the patients’ medical conditions and are still learning about putting an occupational therapy treatment program together. Hence conditional reasoning seems to be more pervasive in the thinking of experts rather than novice therapists.28,67

To convey a sense of the patient’s past, present, and future and to map out how therapy is progressing, the therapist may remind the patient (and self) of a time when the patient could not do a task or activity. This may be particularly useful when therapy is progressing slowly or some of the routine aspects have become boring. Importantly, these reminders show the patient and therapist how the condition is progressing and that together they may yet reach their shared vision of the future.22 For example, to encourage Sam, Sally talks about how much improvement he has made and how this helps him toward his goal of independent living.

Intervention session, part 7.

“I’m just saying to him, ‘Sam, you’ve made such great progress.’ I remind him of when he first started in the kitchen and his endurance really limited how long he could work, and we used to make really simple meals like toasted sandwiches. And now he can make a stir-fry, and he can use his right hand to stabilize very effectively when he chops vegetables, and how he can concentrate for much longer on the job. I find Sam responds really well to reminders of how far he’s come and how far this will get him in the future in terms of living in a more independent home environment, and that’s a real motivator to keep going in therapy.”

To summarize, Mattingly and Fleming44 use the term conditional in three different ways. In its most simple form, the therapist thinks about the patient’s whole condition and the meaning attached to this. The therapist also thinks about how the patient’s condition could change and what this would mean for the patient, and finally the therapist thinks about whether the imagined life will be achieved and realizes that this is conditioned on the patient’s participation in the therapy program and the shared image of the future.

Pragmatic reasoning

Schell and Cervero56 reviewed Fleming’s23 conceptualization of the three tracks of clinical reasoning and postulated theoretically that this account of reasoning neglected the reasoning surrounding the environmental influences that affect thinking and the therapist’s personal context. They referred to these kinds of reasoning as pragmatic reasoning. They suggested that organizational, political, and economical constraints and opportunities affect a therapist’s ability to provide an occupational therapy service, as do personal motivation, values, and beliefs. In the following example, Sally describes how at the facility in which she works, she must use the Functional Independence Measure (Adult FIM, 1995) as an outcome measure.27

Evaluation session, part 4.

“Last week just before Sam’s discharge from inpatient care, I rescored his FIM and discussed that with the team as well. We use FIM as one of our outcome measures here. I don’t really mind doing it, but like I have no choice anyway since that’s what management has said we’ll do.”

Therapy often is constrained or promoted by issues over which the therapist may have little control, such as reimbursement for service, the kinds of services and equipment that can be provided given the patient’s length of stay, whether the patient can afford to purchase equipment, and the kinds of services available in the community for the patient on discharge.69 Another important note is that pragmatic reasoning as influenced by the environmental/practice context appears to interface directly with therapists’ procedural, interactive, and conditional reasoning. In the earlier example, when reasoning conditionally, Sally also reasoned pragmatically about how Sam’s residential options were constrained by the number of available supported community housing places.

Time pressures are another common source of pragmatic reasoning. Therapists must consider what can be achieved in one session or across the patient’s admission. Therapists feel the pressure of patients waiting for them and having to treat more than one patient at a time. Sally also talks about having to share therapy time when the patient is at his or her best.

Evaluation session, part 5.

“We are trying to gradually increase his endurance, but you get to the stage where his face is going to fall into his cereal, [and] there’s no point. You just have to sort of respect that fatigue and also respect the role of the other therapists, because if I see him first, it’s not fair if I exhaust the guy, and everyone else gets nothing out of him, either in physical therapy or neuropsych. assessment or whatever it may be.”

The author’s empirical research has shown that although many instances of pragmatic reasoning were found in the transcripts relating to the therapist’s practice context, few related to the therapist’s personal context.69 Hence one really must question whether pragmatic reasoning is in fact only concerned with the practice context and whether the therapist’s personal context is not related to clinical reasoning but to something else.

Worldview

Worldview is a useful term to describe the influence of the therapists’ personal views about life on their thinking and reasoning. Although Schell and Cervero56 proposed that these personal belief and values form the personal context component of pragmatic reasoning, one has difficulty imagining that therapists could reason actively with their deeply held sociocultural beliefs.69 Rather, personal context seems to be something that influences clinical reasoning. The term worldview seems to be the best way to describe the factors that make up one’s personal context.72,76 Worldview commonly is understood as an individual’s underlying assumptions about life and reality.31 Hence it encompasses the therapist’s ethics, values, beliefs, faith and spirituality, and motivation. If the therapist’s worldview influences reasoning, then the therapist also must acknowledge that this may be a positive or negative influence. Therapists also must recognize that they have varying degrees of insight to the influence of their worldviews on reasoning and therefore varying ability to modulate this influence if desired. The most popular method of researching clinical reasoning is for the researcher to ask the therapist to tell what he or she is thinking about after a therapy session has ended.68 As mentioned previously, in the author’s research, it was discovered that therapists rarely if ever revealed any information about their worldviews or how this influenced their reasoning. This is not surprising given that worldview beliefs are deeply held and that individuals find that they cannot, or may not want to, articulate these beliefs. Hence, it is difficult to research and gain an understanding of the influence of worldview on clinical reasoning.69 However, in some brief glimpses to her worldview, Sally’s transcripts did reveal the personal satisfaction she gains from working with patients who have neurological problems.

Evaluation session, part 6.

“I think OTs [occupational therapists] are really great at empowering people and help them to feel they are in control and they have some say. I think OTs do that better than a lot of other professions. . . . I love to work with people with disabilities, so I think if you actually enjoy the contact and seeing people achieve things, it’s such a rewarding job. That comes across in your approach.”

The transcripts also revealed Sally’s disappointment that Sam cannot achieve what she considers his potential because of drug use.

Discharge session, part 2.

“Even though he’s motivated and you can say, ‘Sam, you’ve just made such amazing gains,’ when he does use drugs, he just loses all his cognition basically. He sits there, and his mother reports he spaces out for 24 hours at a time, and it’s a real shame. I have seen this fellow going from being full assistance in absolutely every activity of daily living to being fully independent in personal care, basic domestic activities, and basic community activities, so he really has done remarkably well, so it’s a bit disappointing. You try not to dwell on it too much, but it is disappointing from a therapist’s point of view because you think he could just keep on improving, but the drug use is holding him back, but at the same time that’s his life.”

Although Mattingly and Fleming44 did not describe worldview specifically or its relationship to clinical reasoning, their text is rich with descriptions of how the therapist’s personal qualities, abilities, or style influences therapy. Further research is required, perhaps using interview techniques, to explore the relationship of therapists’ worldview to clinical reasoning.69

Generalizing form of reasoning

Finally, in each of the forms of reasoning discussed before (procedural, interactive, conditional, and pragmatic), research has shown that therapists seem to draw on their experiences to enrich the kind of reasoning in which they are engaged.70 Rather than being described as a separate form of reasoning, this form of reasoning seems to be an extension of the other forms. The author calls this generalization reasoning. Although generalization reasoning has similarities to simple pattern recognition (as described in relation to pragmatic reasoning), it appears to go beyond simple pattern recognition of a set of cues. Therapists seem to reason initially about a particular issue or scenario with a patient, then reflect on their general experiences related to the situation (i.e., making generalizations), and then refocus the reasoning on the patient. This seems to occur in rapid succession, as in the following excerpt in which Sally reasons interactively about how she is communicating with the patient.

Intervention session, part 8.

“Often, if I can, I try to decrease the verbal cues and actually look at giving some physical cues as well. That carries right over to all of his program. Physically, even though he has significant problems in all areas in terms of transfers and bed mobility and everything. So, for example, when we do personal care, I really have to use a combination of both physical cues and verbal prompting. I’m trying to certainly decrease that. I think with Sam and a lot of patients with stroke or brain injuries, it just takes much longer for them to respond. It just doesn’t go in a quickly as it does with us. My strategy with Sam at the moment is give him the instruction or prompt him and then give him some time to respond, and then go on to give him some physical guidance as well.”

In summary, this generalization form of reasoning seems to enrich the other reasoning modes and also seems to be used more frequently by expert rather than novice therapists.70

Embodied knowledge

This chapter has explored the clinical reasoning and thinking that underpins occupational therapy practice. However, this reasoning is a product of cognitive or mental processes and body experiences. Therapists’ bodies obtain a great deal of information as they work with clients. For example, their bodies tell them about the client’s smell, and the feel of their muscles and how their body moves in ways that the therapists’ own bodies recognize or “know” but that they might not be able to put into words. This is referred to as embodied knowledge.58 In the case study illustrating this chapter, Sally described how she would automatically smell Sam as soon as he arrived at therapy to help determine if he had been smoking drugs. Although occupational therapists have long recognized the importance of information from their bodies about their clients, the embodied nature of clinical reasoning is a relatively new area for research in occupational therapy.

Putting it all together: a summary of the different modes of reasoning

Before summarizing the different kinds of clinical reasoning and influences on reasoning such as worldview, exploration of the interaction of the three tracks of clinical reasoning is important. Although some researchers examine procedural, interactive, and conditional reasoning in isolation from each other,28 it seems that these forms of reasoning can occur in rapid succession or even simultaneously. As described earlier, Fleming22 described how therapists can think in “many tracks simultaneously.” For example, Fleming23 writes “in using conditional reasoning, the therapist appears to reflect on the success or failure of the clinical encounter from both the procedural and interactive standpoints and attempts to integrate the two.” Although the notion of the simultaneous use of the three tracks should not be taken too literally, therapists certainly can see evidence in their clinical reasoning transcripts of the rapid blending of different modes of reasoning. For example, Sally uses all three forms of reasoning in the following brief explanation of one aspect of her therapy session. Procedural reasoning is underlined, conditional reasoning is in bold, and interactive reasoning is italicized.

Intervention session, part 9.

“Another thing I’m working on with Sam is his speed. He’s very slow to process information and therefore slow in executing tasks, and I find that he also tends to self-distract a fair bit by chatting. But at the same time that’s hard because I’m Sam’s case manager, which means that I monitor his whole program, and since he’s just gone home, we have been having long chats about how he was coping at home since I want to find out how he’s doing and what he’s having difficulty with, whether he’s following through by making his own breakfast and using his dressing aids and things like that, so in a way I’m distracting him a little bit, but he has to learn to cope with distractions in his environment.”

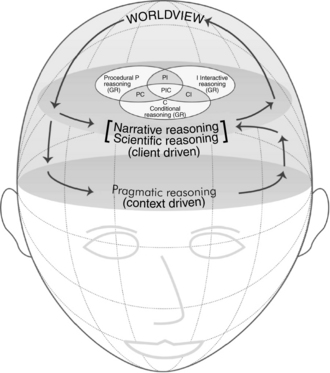

The relationship between the three main modes of reasoning can be illustrated by the use of a Venn diagram in which the three circles each represent a different mode of reasoning and yet show that each mode does not occur in isolation from the others.70 These three forms of reasoning are related to the other modes described in this chapter, as illustrated in Fig. 17-2.69 Fig. 17-2 presents the relationships between the different forms of reasoning, or influences on clinical reasoning, using the analogy of the basic structures of the brain. Starting at the top of this figure is worldview. This was described previously in the chapter as an influence on reasoning rather than a form of reasoning. Worldview is at the top of the diagram because it influences all the modes of reasoning, and like the idea of higher cortical function, worldview represents fairly sophisticated thinking that includes one’s morals, ethics, and sociocultural perspective. The next level of the brain can be described crudely as the engine or working areas. Hence, this is where the main forms of reasoning (procedural, interactive, and conditional) occur, as illustrated using a Venn diagram. These forms of reasoning are more scientific (such as procedural reasoning) or draw more on phenomenological forms of thinking and therefore can be described as narrative forms of reasoning (such as interactive and conditional reasoning). At this level, the therapist’s reasoning is basically driven by the patient (such as the patient’s strengths and weaknesses, goals, and desires). Finally, at the most basic level of operation, which is similar to the brainstem, is pragmatic reasoning. Similar to fundamental brain functions such as breathing, pragmatic reasoning involves thinking related to things over which therapists often do not have much control. For example, the therapist reasons pragmatically about what might be achieved with a particular patient given the patient’s maximum length of stay, which often is dictated by the payment or reimbursement system. In contrast to the patient-driven forms of reasoning described previously, pragmatic reasoning is context driven. Generalized reasoning can occur in connection with procedural, interactive, conditional, and pragmatic reasoning. The arrows that flow around Fig. 17-2 indicate that each influence on reasoning or form of reasoning influences the others to a greater or lesser extent. Finally, one must acknowledge that this representation of clinical reasoning operates within the patient-centered practice of occupational therapy. In other words, this diagram assumes that therapists practice within a patient-centered framework. Hence, the client’s goals, values, beliefs, and life experience are at the forefront of the therapist’s reasoning and drive the therapy process.

Figure 17-2 The relationship between the different forms of clinical reasoning within the patient-centered practice of occupational therapy. GR, Generalized reasoning.

(From Unsworth CA: Clinical reasoning: how do pragmatic reasoning, worldview and client-centredness fit? Br J Occup Ther 67[1], 10-19, 2004.)

Clinical reasoning and expertise

Differences between the clinical reasoning of novice and expert therapists

Over the past 15 years, research in health sciences has shown consistently that experts have better general problem-solving and clinical reasoning skills than novice therapists.65 The occupational therapy literature contains a wealth of information about the differences in the clinical reasoning of novice and expert therapists14,28,52,64 and how students can improve their reasoning skills.12,33,46-49 The purpose of this section is to review what is known about the clinical reasoning of expert therapists and strategies to enhance clinical reasoning so that students and novice therapist can hasten their own journey to expert status.

Like most skills, clinical reasoning can be graded along a continuum. Different points along the continuum are marked by certain characteristics that indicate an individual’s skill level. Dreyfus and Dreyfus18,19 presented a five-stage model of skill acquisition based on their study of chess players and airline pilots. They suggested that as students develop a skill, they pass through five stages of proficiency: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert. Benner6 and Benner and Tanner8 incorporated this model in their studies of the acquisition of skill in nursing, and since that time, most health science research regarding clinical reasoning incorporates the Dreyfus and Dreyfus model. Benner6 suggested that as a therapist passes through the five stages of proficiency, changes in three aspects of skilled performance occur. A shift in reliance from abstract principles to past experiences occurs, a change in perception of the situation occurs (i.e., a shift from perceiving all parts of the picture equally to viewing the whole situation in which only parts are relevant), and a change from detached observer to involved performer occurs. Based on the work of Dreyfus and Dreyfus,18 Benner,6 and Benner and Tanner,8 Table 17-1 outlines the stages in the development of expertise and some of the characteristics of therapists at each stage.

Table 17-1 Stages and Characteristics in the Development of Expertise

| STAGE | THERAPIST CHARACTERISTICS |

| Novices do not have experience of the situations in which they will be involved. To enter the clinic and gain experience in these areas, students are taught about theories, principles, and specific patient attributes. A novice is usually rigid in the application of these rules, principles, and theories. However, rules cannot guide the therapist to do all the things that need to be done in the multitude of situations and contexts in which the therapist works.6 A clinician can acquire only “context-dependent judgment” through participation in real situations.49 |

|

| Advanced beginners have been involved in enough clinical situations to realize, or to have had pointed out to them, the recurring themes and information on which reasoning is based. An advanced beginner may begin to modify rules, principles, and theories to adapt them to the specific situation. Advanced beginners do what they are told or what the text dictates as the correct procedure but may have difficulty prioritizing in more unusual circumstances those parts of the procedure that are least important or those aspects that are vital. Advanced beginners have to concentrate on remembering the rules and therefore have less ability to apply them flexibly. Dreyfus and Dreyfus18 suggest that an awareness of the client as a person beyond the technical concerns does not usually develop until the student has advanced to this stage. |

|

| Competent therapists are able to adjust the therapy to the specific needs of the patient and the situation but may have difficulty altering initial treatment plans. Benner6 suggests that therapists are competent once they are consciously aware of the outcome of their actions. This is typical of a therapist who has been in the job for 2 to 3 years. However, a competent therapist is said to lack the speed and flexibility of the proficient therapist. Efficiency and organization are achieved at this stage through conscious or deliberate planning. | |

| Proficient therapists are flexible and are able to alter treatment plans as needed. Proficient therapists have a clear understanding of the patient’s whole situation rather than an understanding of the components alone. Proficient practitioners have a perception of the situation based on experience rather than deliberation. Given that the proficient therapist has a perspective of the overall situation, components that are more and less important stand out, and the therapist can focus on the problem areas. | |

| Expert therapists approach therapy from patient-generated cues rather than preconceived therapeutic plans. Experts anticipate and quickly recognize patient strengths and weaknesses based on their experience with other patients. The expert therapist does not need to rely on rules and guidelines to take appropriate action but rather has an intuitive grasp of the situation. Experts often find it difficult to explain this intuition.49 |

From Unsworth CA: Cognitive and perceptual disorders: a clinical reasoning approach to evaluation and intervention, Philadelphia, 1999, FA Davis.

Research with occupational therapists and other allied health professions has revealed a variety of aspects of clinical reasoning processes that differ between novices and experts. For example, Collins and Affeldt14 suggested that whereas novices tend to focus on one aspect of a situation and one observation triggers one association, experts can focus on many aspects of a situation and a single observation can trigger multiple associations. Although a more experienced therapist may reason holistically and react quickly to a problem with a total solution, a novice may reason step by step and react more slowly to a problem with only a partial solution. Robertson52 supported this empirically through research that found that more experienced therapists had more integrated problem representations (that is, a well-organized body of knowledge). In addition, because occupational therapists reason in narratives, therapy is like telling or creating a story.44 Mattingly and Fleming44 suggested that expert therapists have a greater capacity than novices to make revisions to the story as therapy progresses.

Other differences between novices and experts include the way experts reason intuitively and have more tacit knowledge. This contrasts to the reasoning of a new practitioner, which seems to require conscious effort. Strong and colleagues64 reported that experts viewed gaining an understanding of their patients in terms of their illness and disability and of patients’ perceptions of the effect of these on their lives as more important than did student therapists. Students placed a higher value on knowledge and understanding of the patient’s problems, whereas expert therapists placed more emphasis on good communication skills. Hallin and Sviden28 also found that expert therapists seemed to have an excellent understanding of the patient.

Finally, my research on the differences between the clinical reasoning of novices and experts67 found that experts make complex skills look simple. The experts in this study were articulate and able to present the clinical reasoning that supported their therapy with confidence. Similar to the findings of Mattingly and Fleming,44 Hallin and Sviden,28 and Benner, Hooper-Kyriakidis, and Stanard,7 experts seem to draw on their past experiences when planning and executing therapy and use this knowledge to anticipate patient performance and modify or change the therapy plan as needed. In addition, although the students in this study had had recent exposure to literature on patient-centered practice, the expert therapists appeared to have embraced this concept and were incorporating this approach in their work. Robertson52 also noted this trend. Finally, expert therapists seemed to have a greater capacity to undertake an activity that met several patient goals or were more likely to be doing several things with the patient at once. Rather than suggesting that they were impatient or pressured by time, this finding indicated an efficiency of time use that novices had not yet developed.

Enhancing the student’s clinical reasoning skills

The progression of a therapist from novice to expertise is not assured. Although some therapists reach competent or proficient practice levels of expertise, they may never attain expert status. In addition, as can be understood from the foregoing examples, expertise is not necessarily reflected in the depth or breadth of experience nor years of practice. Therefore, a relatively young therapist might possibly possess an intuitive grasp of the situation, generate therapy from patient-generated cues, recognize patient strengths and weaknesses based on past experience, and thus be considered an expert. This section presents a summary of ideas from occupational therapy literature that examines how students and novice therapists can improve their clinical reasoning and thus hasten their journey from novice to expert. More specific details of teaching strategies to enhance student’s development of clinical reasoning skills may be found in Higgs29 and Neistadt.46

The following list provides example strategies for novice and student therapists to try that will assist them better in honing clinical reasoning skills.

Learn about clinical reasoning and the different modes of reasoning. When undertaking cognitive and perceptual dysfunction coursework, try to integrate this with knowledge of clinical reasoning techniques.46,66 In these courses, scientific and procedural forms of reasoning can dominate to the extent that insufficient attention is paid to the patient’s experience of the disability, priorities, and life story.49

Learn about clinical reasoning and the different modes of reasoning. When undertaking cognitive and perceptual dysfunction coursework, try to integrate this with knowledge of clinical reasoning techniques.46,66 In these courses, scientific and procedural forms of reasoning can dominate to the extent that insufficient attention is paid to the patient’s experience of the disability, priorities, and life story.49

Spend time reflecting on the patient’s experience of the illness and disability and the patient’s perceptions of how these affect his or her life. One might achieve this after a patient interview in which the student/therapist asks the patient about what the disability means to him or her and its effect on life.59,64

Spend time reflecting on the patient’s experience of the illness and disability and the patient’s perceptions of how these affect his or her life. One might achieve this after a patient interview in which the student/therapist asks the patient about what the disability means to him or her and its effect on life.59,64

Use case scenarios from experts to make expert therapist reasoning and hypothesis generation more explicit. In this way, students can learn to model their practice on an expert’s.52 Students can generate their own case studies and work in pairs to describe evaluation and treatment processes and thus facilitate self-evaluation and critical reflection.46 As Mattingly and Fleming’s study44 revealed, mentoring from an expert therapist is just as influential as formal education is on a novice’s practice.