chapter 21 Enhancing performance of activities of daily living

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following:

1. Understand the occupational therapy process using a client-centered top-down approach.

2. Recognize the effect of a stroke on a person’s engagement in activities of daily living.

3. Discuss the occupational therapy reasoning process for enhancing engagement in activities of daily living.

4. Understand the basics for documentation and goal writing during the whole intervention process.

5. Understand the different models of interventions used for instrumental activities of daily living.

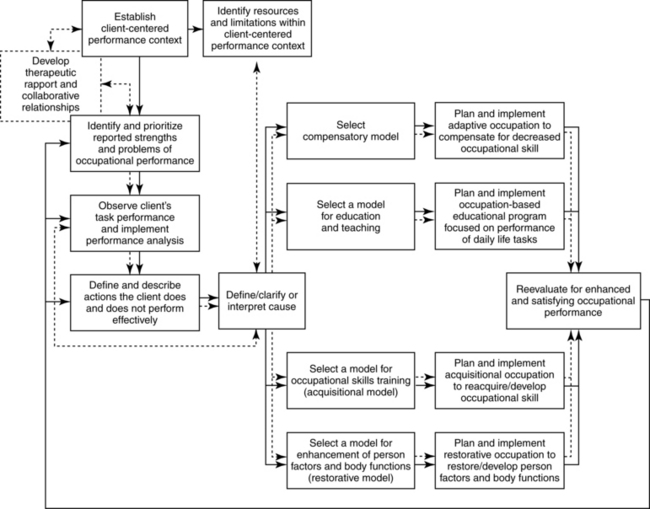

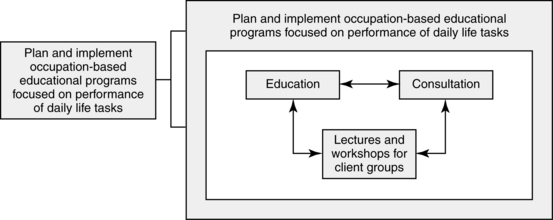

In this chapter, two cases will be presented where the occupational therapist has used an intervention process to enhance the performance of activities of daily living (ADL) after stroke. The process model used is occupation-based, top-down, and client-centered. The Occupational Therapy Intervention Process Model (OTIPM)3 has been used at the hospital where the two cases are being treated for over ten years and is the base for a general program used for all patients at the occupational therapy (OT) department. The complete process model is shown in Fig. 21-1, and all steps will be described in the two cases, Astrid and August. This chapter focuses on leading the reader through the client-centered intervention process and on showing how the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) can be used as a guide in planning OT interventions.

Figure 21-1 Occupational Therapy Intervention Process Model.

(From Fisher AG: Occupational therapy intervention process model, Fort Collins, Colo, 2009, Three Star Press.)

Within stroke rehabilitation, there is a growing body of knowledge that patients will benefit from a team approach to rehabilitation, from the acute to the later stages of the rehabilitation.9 At the rehabilitation department where the cases in this chapter participated, the team works with an interdisciplinary view where the client is included in the team as a member. Together with the client, all team members participate and formulate the goals at the initial planning meeting. The occupational therapist’s contribution to this team approach has a clear focus on the client’s ability to perform those daily tasks that he or she wants the ability to do and that hold meaning given the circumstances in which the client lives.15 It is, therefore, important that the occupational therapist start the intervention process by finding out the areas of interest and meaning for each individual client. To do so means that the occupational therapist uses so called top-down reasoning, which immediately gives the occupational therapist knowledge about the areas in the client’s everyday life that he or she views as most important, given the current situation. Top-down reasoning is separated from bottom-up reasoning, where the occupational therapist initially focuses on evaluating the client’s body functions and/or environmental factors. The identified decreased functions are then viewed as the cause of the client’s problems in the everyday doings.

In Sweden, where these cases take place, it is common practice to develop an OT program that describes the services that OT may provide to a specific client group in a particular setting. In Västerbotten County, a group of occupational therapists developed a general program from which more specific programs can be developed. These programs are based on Fisher’s OTIPM;3 the general OT program developed in Sweden is also included in Fisher’s text.3 The OTIPM describes the process from the first meeting with the client and the different OT interventions and through the whole rehabilitation process until the final meeting with the client. The description of the two cases will use this model to clarify the process and to suggest interventions for the specific cases. The OTIPM will be used to demonstrate how OT services can be provided in a manner that is top-down, client-centered, and occupation-based.

The cases will be described according to the OTIPM model and, according to the OT program used at this particular rehabilitation unit (see Fig. 21-1).

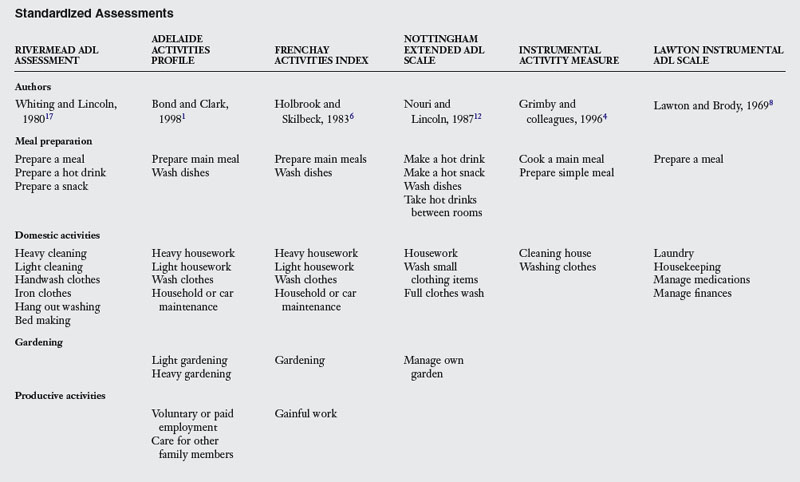

As the intervention process progresses, evaluations will be used to help each step of the process. One of the main sources of information gathering on the actual ability to perform daily tasks is the AMPS.2 Other standardized assessments can also be used to document the status of performance of ADL after stroke and are summarized in Table 21-1.

The AMPS is a standardized evaluation of personal and instrumental ADL, which can be performed with persons with any diagnosis and at any age from 2-years-old to over 100-years-old, as long as the person is interested in and has experience doing daily tasks. To become a trained and calibrated AMPS rater, the occupational therapist must attend a five-day training course and test 10 people after the course. When the potential rater demonstrates the ability to score AMPS in a valid and reliable manner, he or she becomes a calibrated AMPS rater and has full access to reports generated by the AMPS computer scoring program. The use of these reports in practice will be demonstrated in this chapter.

The AMPS is an observational method of evaluating a person’s skills in daily tasks. In all, 36 skills are evaluated: 16 ADL motor skills and 20 ADL process skills (Box 21-1). There are 86 different standardized tasks that are standardized in the AMPS. Both personal and instrumental ADL tasks are included. The tasks represent several different cultures and levels of difficulties. Each person is observed doing two or more tasks and is scored on each of the 36 items for each task. Examples of standardized tasks are listed in Box 21-2. To implement an AMPS observation, the process includes finding out relevant and challenging tasks for the client to perform in order to get the most complete and comprehensive evaluation of the client’s performance. Several steps are required in order to conduct an AMPS evaluation according to the standardized procedures.2 After the observation, the scores are then entered into the AMPS software, and several reports can be generated that will assist the occupational therapist in the intervention planning process.

Box 21-1 The Items Observed and Evaluated in the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS)

List of the motor and process skills observed during task performance:

From Fisher AG: Assessment of motor and process skills, ed 6, Fort Collins, Colo, 2006, Three Star Press.

* Paces is considered both a motor and a process skill

When the AMPS is used in its full potential as a standardized tool, it will generate two ability measures that will inform the therapist and the client about ADL ability in relation to effort, efficiency, safety, and independence. Occasionally, the occupational therapist calibrated as an AMPS user meets a client where none of the 85 tasks are relevant to the client. In those occasions, the occupational therapist can perform a nonstandardized AMPS evaluation by observing the client doing a task of relevance that is an appropriate challenge and chosen by the client. During this instance, the therapist cannot use the AMPS software, but can get detailed information on which of the skill items the client has problems performing and can use that information in the documentation and the continuing process of planning and implementing interventions.

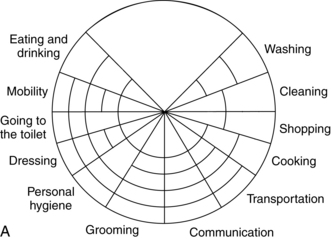

There is also another ADL assessment available to use as a structure during a first meeting with a client.”14,16 This ADL-taxonomy is conceptualized as a divided large circle where each area of daily tasks has its own slice (Fig. 21-2, A and B). All slices are then divided into the actions included in each task domain according to a hierarchy of difficulty. The areas include eating and drinking, mobility, going to the toilet, dressing, personal hygiene, grooming, communication, transportation, cooking, shopping, cleaning, and washing. Located at the top of the circle is a blank slice where the occupational therapist can add areas of importance to the client that are not included in the listed areas (i.e., leisure tasks).

Figure 21-2 A, The ADL Taxonomy. B, Operational Definitions of Activities and Actions included in the ADL Taxonomy.

(A is from Törnqvist K, Sonn U: Towards an ADL taxonomy for occupational therapists, Scand J Occup Ther 1[2], 69-76, 1994. B is from Sonn U, Törnqvist K, Svensson E: The ADL taxonomy - from individual categorical data to ordinal categorical data. Scand J Occup Ther 6[1]:11-20, 1999.)

In rehabilitation departments in Sweden and elsewhere, it is common to work with interdisciplinary teams.5 This means that several professions are involved in the whole rehabilitation process, and members contribute their specific expertise to the team through their profession specific assessments, which allows them to get the full picture of the patient needs. The team members collaborate closely and assist each other in solving problems that arise during the rehabilitation process. The patient is a member of the team. The patient’s rehabilitation goals are the basis for the goals of the team, and they guide the decision about which team members to involve in the rehabilitation process, a decision that can also change over time as the goals change.5,11 The following two cases show when and how this interdisciplinary teamwork is implemented in the rehabilitation process.

Geriatric day rehabilitation: client living in comfort (assisted) living

Astrid is a 72-year-old woman who had a stroke eight months ago. The computerized tomography (CT) scan showed a cerebral hemorrhage in the basal ganglia through to the ventricles on the left side of the brain. She had a right-sided hemiparesis, aphasia, and she was substantially depressed. Initially, she had low arousal due to the cerebral edema and received rehabilitation for two weeks on the stroke unit in the hospital.

She required substantial assistance to transfer into her recliner wheelchair. The staff used a sling attached to the ceiling to move her from bed to chair.

She required substantial assistance to transfer into her recliner wheelchair. The staff used a sling attached to the ceiling to move her from bed to chair.

She required a two person assist for her hygiene and dressing, which was done bedside, although she did try to participate when she was able.

She required a two person assist for her hygiene and dressing, which was done bedside, although she did try to participate when she was able.

She had aphasia, but she could answer yes and no to questions, and she did understand simple encouragements.

She had aphasia, but she could answer yes and no to questions, and she did understand simple encouragements.

Two weeks after her stroke, she was moved to the geriatric rehabilitation unit and met an occupational therapist the first day. Since Astrid had difficulty speaking and was easily fatigued, the main information was gathered via medical records and through telephone contact with one of Astrid’s daughters.

The rehabilitation goals at this subacute stage included:

1. To be able to propel independently in the wheelchair on a flat surface

2. To transfer from wheelchair to bed or toilet with verbal instructions and support handles

3. To know the day of the week, time of day, and the date

4. To adjust the temperature of the water from the faucet

5. To manage upper body grooming and dressing independently

6. To make own breakfast (i.e., make cooked oatmeal independently)

At the time for discharge from the geriatric rehabilitation unit three months later, the first four goals were met. Tasks included in goal numbers five and six still required physical assistance. A referral was sent to the geriatric day rehabilitation unit for continuing rehabilitation. Astrid moved to a “comfort living” complex for elderly and had access to home care 24 hours a day. Comfort living is the client’s own apartment in a complex for older persons with access to jointly owned areas and dining room.

Establish client-centered performance context

About two months later and now five months after the stroke, Astrid was admitted to the geriatric day rehabilitation unit. She arrived with her ex-husband Emil at the first visit with the occupational therapist. The occupational therapist, Maria, carried out an initial interview to establish the client-centered performance context, and she asked Astrid to describe for her how a usual day was laid out. For guidance in the first step, Maria used the OTIPM and ADL-taxonomy, which helped her visualize the daily tasks for the client. Maria summarized Astrid’s occupational performance context according to the ten dimensions in the process model, OTIPM.

Environmental dimension

Astrid had recently moved to a comfort living complex for elderly persons (55+). Her apartment has two rooms and a kitchen, and it is adapted for functional limitations. The bedroom has a bed with rails, a book shelf, and a bedside table close by with a telephone, a digital day and night calendar. The living room has a sofa, armchairs, a TV, and a dining room table with two chairs close to the kitchen area. In the kitchen, there is a refrigerator and microwave oven located high up. Astrid can reach the lowest shelf in the refrigerator from her wheelchair. The apartment has a large bathroom with a shower, including a shower stool and toilet with a raised seat and armrests. The bathroom also has a washing machine and tumbler. In her current living arrangement, Astrid has access to home care staff 24 hours and can also use the jointly owned areas of the living complex, i.e., dining room, library, TV room, and spa unit. Astrid does not use these areas because of her current problems with mobility, and she cannot propel the distance required for this.

Social dimension

Astrid has a lot of support from her ex-husband Emil, who is now responsible for her finances. She has some close friends as well. Prior to her stroke, she lived alone in her own apartment and managed all her daily tasks on her own. Astrid is divorced and has two grown daughters, one in the south of the country and one abroad. Earlier she often traveled to her daughters and their families and spent a lot of time with her grandchildren. Now they will have to travel to her instead.

Role dimension

Astrid is a mother and caretaker. Previously Astrid spent a lot of time in the forest, picking wild berries and mushrooms, and enjoying walks. She also has a great interest in gardening. Being together with friends and participating in the city’s culture such as theatre, concerts, and movies have also been important interests of hers.

Cultural dimension

Astrid is a typical Swedish woman, and her cultural beliefs, values, customs and where and how she performs her daily life tasks are similar to other persons in Sweden of the same age.

Motivational dimension

Astrid enjoyed keeping her home nice and tidy. She has also read several journals about gardening and home decorating and fictional books. She is motivated to invite her friends to her apartment and wants to be able to do that independently. When she currently has visitors, the guests have to make their own coffee. She also wishes to be able to eat a meal using the usual utensils, since it bothers her that others see her using only her fork while eating (in Sweden it is customary to use both knife and fork during a meal, with knife in right hand and fork in left hand during the whole eating process). Because of this, she does not want to eat in the dining room but instead chooses to have the staff prepare her food for her in her apartment. Due to the same reason, she would like to be able to walk without assistive devices.

Astrid would like to be able to manage her daily tasks herself again, such as inviting her friends for coffee, make her own breakfast, make her own sandwich, and manage going to the toilet by herself and safely.

Institutional dimension

Astrid has several resources available to her of which she now needs to make use:

The home help staff to help with her personal hygiene, dressing, and toileting. The staff also helps her to prepare her meals, and they supervise transfers among wheelchair, bed, and toilet. She also receives help with cleaning and shopping.

The home help staff to help with her personal hygiene, dressing, and toileting. The staff also helps her to prepare her meals, and they supervise transfers among wheelchair, bed, and toilet. She also receives help with cleaning and shopping.

Her ex-husband and daughters are responsible for her finances, and her ex-husband supports her in other situations.

Her ex-husband and daughters are responsible for her finances, and her ex-husband supports her in other situations.

Currently she also has support from the team at geriatric day rehabilitation.

Currently she also has support from the team at geriatric day rehabilitation.

Body function dimension

Astrid presents with right-sided hemiparesis and aphasia. She initially presented with low arousal secondary to cerebral edema. Right after the stroke, she sat in a recliner wheelchair and was lifted with a mechanical lift. She also presented with fatigue and depression (which was treated medically). Currently, Astrid’s memory problems and decreased ability to use her right arm and hand are her biggest problems. She has pain in her right shoulder, causing her to have problems moving her arm effectively, although she has good ability to grip with her right hand. Some of her problems can also be related to her apraxia. Astrid wants to be able to walk independently and safely with her rolling walker. Astrid usually sits in her wheelchair and has problems propelling herself, as the chair is too high for her to strike her heel.

Task dimension

Astrid expressed that her greatest problem today is to move herself. She would like to be able to safely walk with her rolling walker. She also thinks it is important to manage by herself as much as possible during her daily tasks. She would like to manage to perform simple everyday tasks on her own, and her highest priority is to again be able to make coffee with cookies for her friends, make her breakfast (oatmeal), make an open-faced sandwich, and eat with knife and fork. She also wishes to be able to write with her right hand again.

Temporal dimension

One ordinary day in Astrid’s life starts when the staff at her living complex comes in and wakes her up at 7:30 am. They help her to her wheelchair, into the bathroom, and onto the toilet. Astrid can do these actions herself with supervision and verbal assistance. She transfers herself to the shower stool and receives help with showering and dressing. She tries to participate as much as possible. After the morning hygiene routine, the staff makes her breakfast. She eats and reads the daily newspaper. She then lies down to rest until lunchtime. The staff then returns, helps her to the bathroom, and makes her lunch. Presently, the staff needs to cut the food into small pieces, so that she can eat with her fork in the left hand. After lunch, Astrid usually has a session of practicing walking with the staff. She will use her rolling walker, and the staff uses a gait belt. In the afternoons, she will often have visitors, who will prepare the afternoon snack for themselves and her. Astrid will rest again before dinner, when the staff comes to her room and helps her to the bathroom and to prepare dinner. In the evening, she watches TV and reads the newspaper. She goes to bed around 9:00 pm. Astrid still fatigues during the day and needs to rest several times. But in between her rests, she would like to manage more daily tasks herself.

Astrid lives at home in the comfort living complex and uses the option to take a taxi (mobility service) to the geriatric day rehabilitation two afternoons every week (between 1:00 and 3:00 pm). She will continue to do so until she meets her rehabilitation goals.

Adaptation dimension

Astrid has difficulty fully participating in an effective manner due to her lack of initiative. Her fatigue also limits her today. Therefore, she needs support from the staff at her living complex and from relatives, so that the rehabilitation can continue during the whole day. The helping staff need to be familiar with Astrid’s problems, so they can best supervise and support Astrid in her daily tasks.

Develop therapeutic rapport and collaborative relationships

When Maria, the occupational therapist, met Astrid, and Emil, they started to develop rapport and identified persons to include in the collaborative relationship during the intervention process.

During this first meeting, Astrid had Emil as a support. His role was to confirm what she tried to say and to provide moral support for her, and as such, he is involved in the collaborative relationship. Astrid managed the interview to a great extent by herself and only occasionally looked at her ex-husband for support when she was unsure. Maria tried to identify the problems that Astrid described as they discussed her everyday habits. Maria also was keen to listen and to show empathy for the situation that Astrid described.

Identify resources and limitations within client-centered performance context

Due to their first meeting, Maria has gathered the information from Astrid that she herself can identify and consider as current resources and limitations. This information will be important for the occupational therapist as background information that she can use throughout the intervention process. The occupational therapist tries to have a focus on occupations as she documents the information that she has gathered from Astrid.

Documentation of initial OT evaluation:

Background Information and Reason for Referral

Background: Astrid is a 72-year-old retired woman that lives in a small apartment in a comfort living complex for elderly and has around the clock service. A rehabilitation plan is made together with the team and Astrid. She uses a wheelchair and would like to be able to walk independently with a rolling walker and to manage simple daily chores herself (i.e., to make her own breakfast, invite friends for a coffee snack, eat with cutlery). She also wishes to be able to use the toilet independently. She survived a left-sided stroke about 5 months ago. She is weaker in the right hand and leg, still has some aphasia (she can make herself understood and understands most conversations), and has impaired memory, impaired initiative, and fatigue.

Reason for referral: Referred to the geriatric day rehabilitation for rehabilitation by the interdisciplinary team. Will be evaluated and receive interventions in daily tasks by the occupational therapist.

Identify and prioritize reported strengths and problems of occupational performance.

Another outcome from the first meeting between the client and the occupational therapist is the client’s self-reported strengths and problems of performance. At this meeting, the occupational therapist can use the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM),7 ADL taxonomy14,16 or other available instruments that guide the interview and give a structure that can support the client in identifying and prioritizing important limitations with daily occupations. Since Astrid has both aphasia and some memory loss, it was difficult to use the COPM. The ADL taxonomy was easier to use with Astrid during this first time, and one of Astrid’s daughters was contacted for further information.

Documentation from initial OT evaluation, part II: reported level of performance and prioritized task performance.

Maria documented the identified strengths and problems according to Astrid’s information as follows:

Self-Reported Level of Performance

Astrid describes that she feels dependent on other persons around her all the time. As she currently requires substantial assistance for her everyday doings, she would like to be able to perform some everyday tasks herself. She prioritizes highest to be able to make coffee and snacks for her friends, to make her own breakfast, eat with cutlery, make an open-faced sandwich, and write with the right hand again.

Observe client’s task performance and implement performance analysis

Presently in the rehabilitation process, it was time for Maria to observe Astrid’s actual performance before they decide about which intervention to initiate. At the next visit, Maria thus had planned for an observation of Astrid’s performance. Astrid chose to make her breakfast. There was no formal AMPS evaluation made at this time, and Astrid chose to make cooked oatmeal for one person, since she usually ate that for breakfast. Although the AMPS was not used as a standardized tool, the occupational therapist could still use the skills of the AMPS to describe the performance. The AMPS skills observed during the performance are inserted in the next section in parentheses.

Observation in prioritized task

To make breakfast.

Astrid was observed in the clinic kitchen as she cooked oatmeal and served jam, milk, and oats. As they set up the environment before the performance of the task, they decided to move the objects that were located high in the cupboards down to the lower shelf so Astrid could reach them. Before the observation, Maria and Astrid located all the tools and materials needed in the task. Astrid started to perform the task and collected all the materials and tools that she needed to make the oatmeal, but she does not gather the salt (initiates, search/locates, gathers). She had an ineffective ability to move herself in the wheelchair in the kitchen, since the wheelchair was too high for her (moves, reaches, bends). She also took a lot of time and effort to gather the objects and to place them for easy access (paces, endures, organizes). She was ineffective as she scooped the oats from the bag with a measuring cup as she held the measuring cup with her right hand and could not reach the oats in the bag that she held with her left hand (grips, coordinates, navigates, handles). She stopped, hesitated, and then moved the bag of oats to her right hand and the measuring cup to her left hand (continues, notice/responds, accommodates). She was now able to gather the amount of oats that she needed from the bag. Astrid then asked for salt, and the therapist gave her a general cue/clue where to find it (inquires, search/locates). Astrid did not organize the materials in an effective manner on her workspace, and there was a risk that she would knock over the milk carton with her left elbow when she reached over to pick up the jam jar (organizes, navigates). She tried to open the jar, but did not have enough strength to open the lid and asked for needed help (coordinates, calibrates, accommodates). She also needed verbal assistance to keep the pan on counter while she scooped the oats into the bowl; she tried with her right hand and then with her left hand, but needed assistance to scoop the oats in a safe manner (coordinates, handles). She served the oats in the bowl at the kitchen table, and restored all items to their original storage place. This task took 45 minutes to complete.

Initial evaluation: observed current level of performance

Global baseline: cooking oatmeal.

Astrid was moderately inefficient and showed moderate increase in effort, from being able to firmly touch the floor with her feet to move a wheelchair properly. She also had a minimal need for verbal assistance for finding the salt, and a moderate degree of physical assistance to open the jam jar and scoop the cooked oats into bowl.

Specific baseline.

Astrid moved herself in her wheelchair with moderate effort, which affected her ability to position herself in relation to the task in order to enhance task performance (e.g., she sat with her left side toward the workplace where her right side was too far away to reach effectively with her right hand). Her awkward sitting affected her ability to organize the tools and material on the workplace. All task objects were placed very close together, and she then bumped into the milk carton with the elbow when she reached for jam. She also had limited ability to safely scoop the oatmeal from the pan. Astrid mobilized herself and task objects in an ineffective manner.

When Astrid was made familiar with the environment in the kitchen, Maria completed a standardized AMPS evaluation to evaluate her OT in an effective manner. The standardized ADL assessment will help the occupational therapist get more detailed information on actions problematic for Astrid. The AMPS is well-suited for the evaluation phase since it will define and describe the actions of performance that Astrid performs effectively or not.

Amps evaluation

The stroke affects Astrid in many aspects of her everyday life and to a great extent. The occupational therapist uses the information she has about Astrid to decide that Astrid must choose tasks that are calibrated as average or easier than average in the AMPS process task hierarchy. Drawing on the list of prioritized tasks that Astrid made earlier, the occupational therapist presented a list of five possible task choices: sweeping the floor, folding laundry, setting a table for four persons, making an open-faced sandwich with meat and a vegetable, and handwashing dishes. Astrid prioritized some of these tasks and wanted to be able to do them independently again.

Astrid chose to make a sandwich with cheese and sliced vegetable (average task difficulty) and to sweep the floor (easier than average task). She decided to start her performance making the sandwich, since she now felt familiar in the kitchen and had knowledge of the location of things she would need. Before the observation, the occupational therapist and Astrid set up the environment to make sure that Astrid had tried to open all cupboards and drawers, including the refrigerator door, and knew the location of all the things she needed. The setting up of the environment is also done prior to each task, so the client has an environment that is as similar to her own home as possible to perform the task. The objects needed in this task were moved from the upper cupboards down into drawers within reach for Astrid sitting in her wheelchair. The actions marked in parentheses in the following text are actions that were recorded as ineffective or markedly deficit according to AMPS criteria.

Astrid chose to start with the task of making a sandwich and decided to make a cheese sandwich with sliced cucumber on top. Astrid demonstrated an inefficient ability to reach into the refrigerator for needed objects, as she placed herself far from the refrigerator with her wheelchair and sat leaning back in the wheelchair (stabilize, reach, bend). She was ineffective in transporting herself in the wheelchair as the chair is too high for her. She placed herself diagonally in relation to the work area, which led to an ineffective way to use her right hand. She tried to spread the butter on the sandwich with the knife in the right hand. She lost her grip on the knife, and, after sometime, she switched to the other hand (grips, manipulates, coordinates, calibrates, flows). The objects in the task were organized close together, leading to problems for her to navigate the workspace. She also had a decreased ability to accommodate and adjust to the situations during the task (organize, navigate, accommodate, adjust). She showed a decreased ability to use objects, as she chose a knife to pick up a slice of cheese and then continued to use the knife to pick up slices of cucumber as well. The task took about 20 minutes for her to accomplish, primarily due to her limited ability to transport herself with the wheelchair in the kitchen.

Since Astrid still had energy, she also wanted to do the second task, sweeping the floor of the kitchen. The verbal contract was that she should sweep the whole floor in the kitchen and move lightweight furniture that were in her way. During this task, she had the same inefficient way of transporting herself (moves), and she tried but was not able to move chairs, which meant that she did not reach (reach) visible crumbs, although she tried to bend forward (markedly decreased ability to adjust). She gripped the brush with her right hand but changed to the left hand and swept with the left hand instead (manipulates, coordinates, accommodates). She navigated inefficiently, and her wheelchair became stuck on a chair that she was not able to move in order to sweep the floor (organize). She did not sweep the whole floor and did not restore until a verbal cue (restore, heed) was given. She asked if she should restore the brush to original place and was scored down for the item terminates.

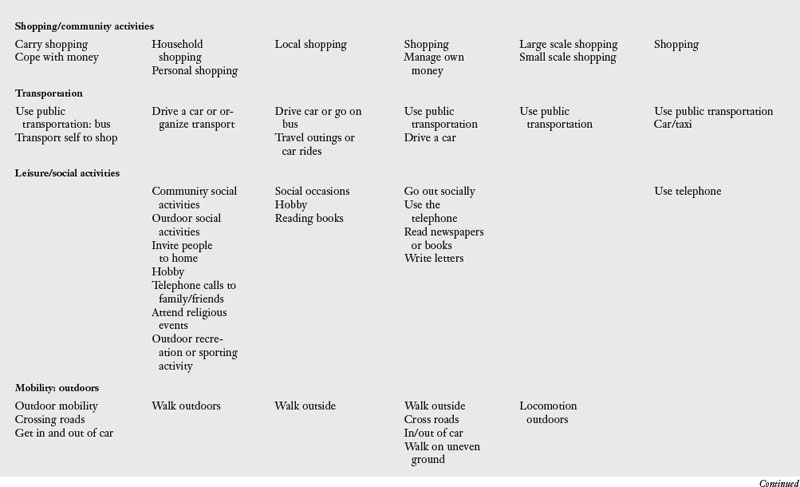

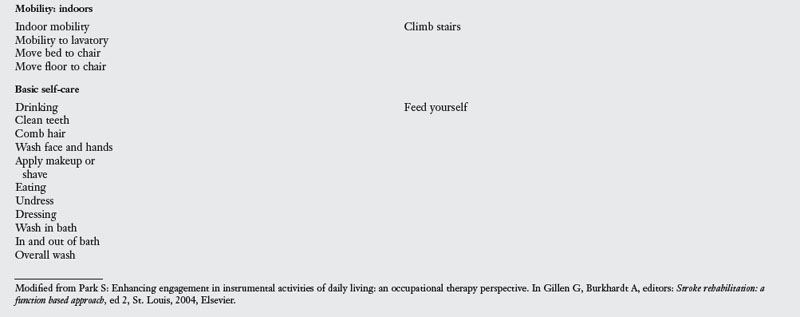

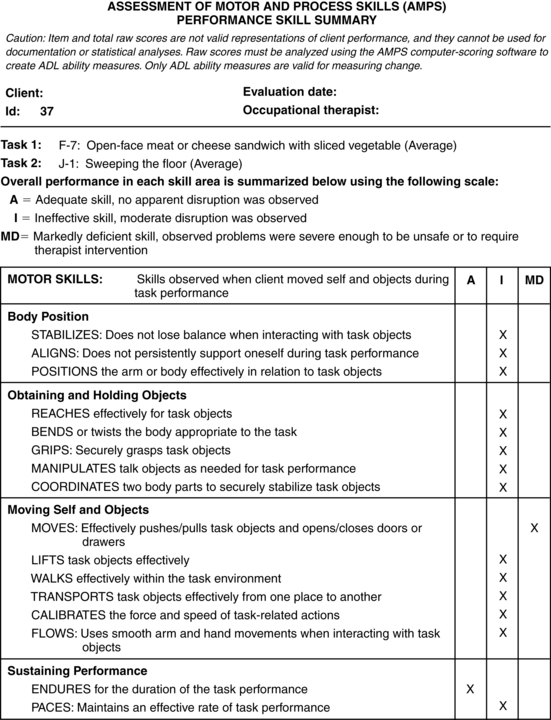

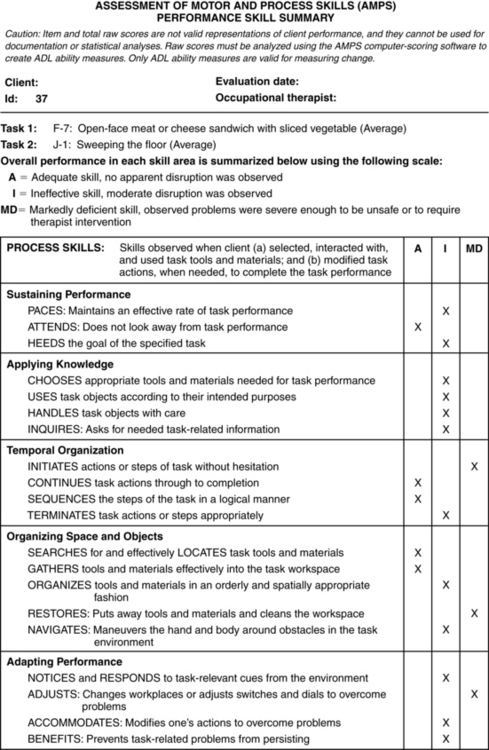

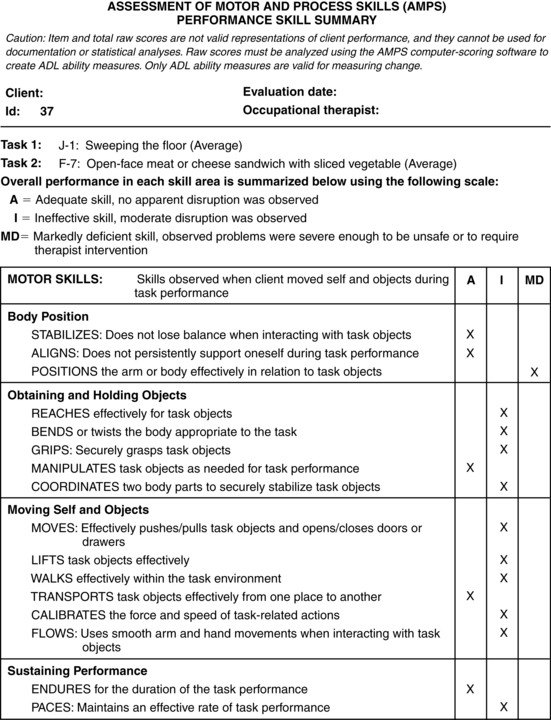

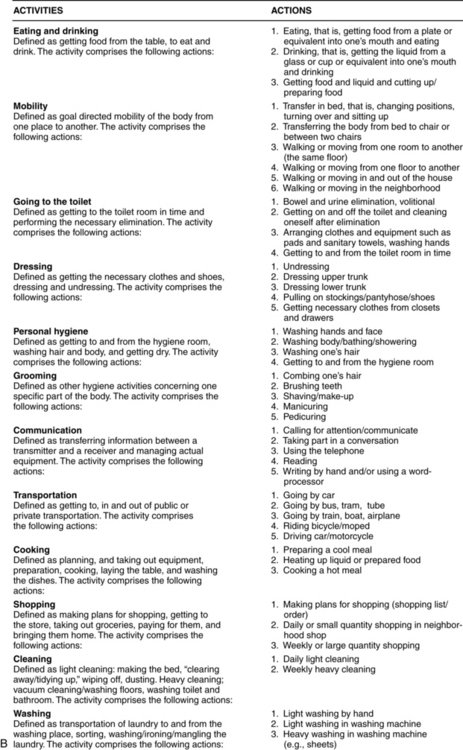

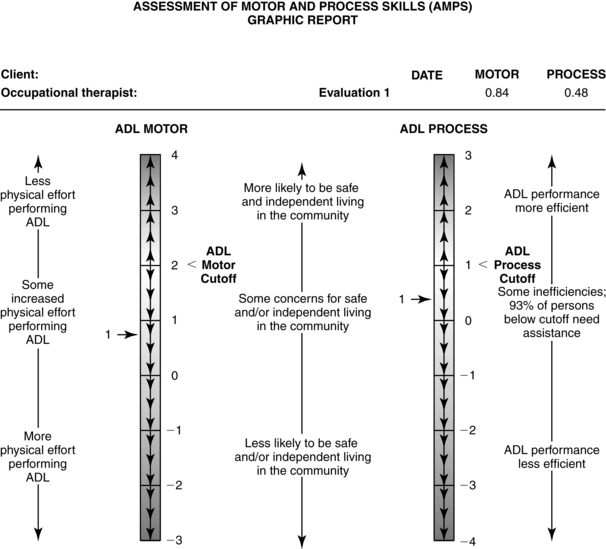

The occupational therapist, Maria, then filled in the AMPS score form and entered the results into the AMPS computer software. See a summary of Astrid’s Motor and Process Skills from the Summary report in Figs. 21-3 and 21-4.

The AMPS software also generates a graphic report (Fig. 21-5) of the motor and process skills indicated on linear measures. Each scale also has a cutoff, where a score below the cutoff indicates problems of performance in terms of effort, efficiency, safety, or need for assistance. The graphic report shows that Astrid’s motor ability is below the cutoff on the motor scale. Astrid’s motor ability indicates that she has increased effort when performing ADL tasks. Approximately 95% of well, elderly persons of her age have ADL motor ability between 1.07 and 3.27 logits, and her ability at 0.01 logits is thus lower than age expectations. Astrid’s process ability is also below the cutoff on the process scale. This indicates that she experiences decreased safety, independence, and/or efficiency when she performs familiar ADL tasks. About 95% of healthy persons of Astrid’s age have an ADL process ability measure between 0.59 and 2.55 logits, thus her ADL process ability at 0.45 logits is lower than age expectations. An ADL process ability measure below 1.0 logits indicates that the person needs assistance. Approximately 93% of persons below the ADL process cutoff need assistance to live in the community. Both Astrid’s cognitive and motor impairments after her stroke affects her ADL performance. More information about the AMPS scales and cutoff can be found in the AMPS manual.2

Figure 21-5 AMPS graphic report of Astrid’s performance at baseline. The numbers on the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) motor and ADL process scales are units of ADL ability (logits). The results are reported as ADL motor and ADL process measures plotted in relation to the AMPS scale cutoffs. Measures below the cutoffs indicate that there was diminished quality or effectiveness of performance of instrumental and/or personal ADL. See the AMPS Narrative Report for further information regarding the interpretation of a single AMPS evaluation.

After the observation using the standardized AMPS, the occupational therapist can also look at the hierarchy of the standardized tasks in the AMPS manual and make assumptions about other tasks in the hierarchy that will be easier or harder for Astrid to perform. For example, since she showed increased effort and decreased efficiency making a sandwich and sweeping the floor, she would have fewer problems with tasks such as folding laundry or making the bed.

Define and describe the actions of performance the client does and does not perform effectively.

Also available from the AMPS software is the possibility to print a narrative report of the observed performance. This report gives information about the AMPS, the observed tasks, and some information about the strengths of the performance. It also includes information on how well the performance compares to persons in the same age group.

Grouping skills of most concern into meaningful clusters.

The next step was to group the skills found to be of most concern into meaningful clusters. These clusters can help document the problems observed in Astrid’s performance. Astrid’s limitations could thus be summarized into the following clusters:

Cluster 1: moves and positions.

Astrid had problems related to moving around in the task environment in an effective manner, which resulted in problems related to positioning herself in an effective way to use the task objects.

Cluster 2: reaches and bends.

She had problems reaching for and reaching into the refrigerator, despite the fact that she tried to bend forward (also due to cluster 1).

Cluster 3: grips and coordinates.

Astrid tried to sweep the floor with the broom in her right hand, but could not hold her grip effectively, and had problems getting the dirt onto the dust-pan.

Cluster 4: paces.

Due to problems in moving herself effectively, she had problems maintaining an acceptable tempo throughout the task. Every task took a long time to finish.

Cluster 5: organizes.

Astrid placed the objects too close to each other, which resulted in problems (i.e., in spreading the butter on the bread as the container was too close to the bread).

The strengths of Astrid’s performance are also summarized, since her strengths could be used as interventions were planned with Astrid during her rehabilitation period. Astrid’s strengths could be summarized into the following cluster.

Cluster 6: endures, attends, continues, sequences, searches/locates, gathers.

Astrid was motivated and endured through both tasks. She stayed focused and continued the performance to the end of the tasks. She completed all of the actions in the correct order and had no problems finding and gathering the tools and materials she needed for the tasks.

Define/clarify or interpret cause

When the occupational therapist has evaluated the quality of the performance of the client, the occupational therapist is ready to clarify or interpret the cause of the problems of occupational performance. When the occupational therapist looked through her notes that summarized the ten dimensions, what she had documented in the patient files, and the information gathered from the other members of the team, it became clear that Astrid’s problems were due to both her limited motor skills and the cognitive impairments that she had acquired from her stroke eight months earlier (body function dimension).

Astrid also demonstrated problems related to organizing the tools and materials in the environment, such as moving the furniture, organization in kitchen, and wheelchair use (environmental dimension). Currently she also did not receive the support to be as independent as possible that she needed from the staff at her living complex.

Documentation from initial occupational therapy evaluation: interpretation of cause

This is what Maria documented in Astrid’s files:

Interpretation

Limited motor skills and cognitive impairments limit the quality of ADL task performance. Lack of sufficient support from others and limited possibility to try and perform daily tasks after stroke further hinder ADL task performance.

Document client’s baseline and goals.

From the AMPS results, it might be important to verify and maybe change some of the rehabilitation goals set together with Astrid. Thus, Maria reasoned together with Astrid that a more realistic goal was to manage some of the tasks with supervision instead of a goal of being independent. She wanted, for example, to make coffee for her friends, and after having observed Astrid, the occupational therapist was aware that it might be more realistic for her to aim to perform this task with some supervision. With the support from her daughter, Astrid was very clear in what she wished to accomplish during her rehabilitation. After the initial evaluation phase, it was time for the team to have a joint meeting and to plan the continuous care and rehabilitation for Astrid. This happened as Astrid arrived for her fifth meeting at the geriatric day rehabilitation. The goals that Astrid and the occupational therapist had agreed upon, and were prioritized by Astrid, are written below. These tasks will be the focus during the following OT visits at the geriatric day rehabilitation two times a week for some time. The following goals were also included in the common team goals.

Goal 1.

Astrid will, with supervision, safely manage to serve coffee and cookies to her friends. This includes brewing coffee, taking out cookies and placing on a plate, setting the table with coffee cups and saucers, and serving at a table (Fig. 21-6).

Goal 2.

Astrid will, with verbal support from the staff at her living complex, initiate and, in an effective and safe way, make herself a portion of warm oatmeal using an adapted work chair (the chair will allow her to reach her cupboards and at the same time allow her to propel her chair in an effective manner).

Goal 3.

Astrid will independently and efficiently make her own sandwich with one spread (i.e. easy spread butter), sliced cheese, and pre-sliced vegetable, using a nonslip device and a rolling work chair.

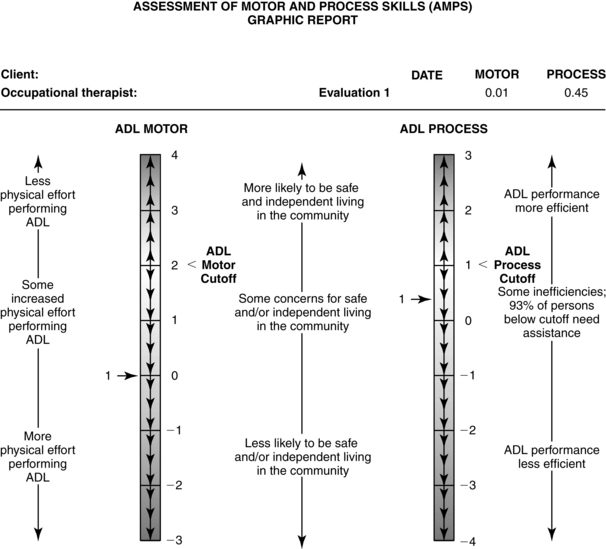

Select intervention model and plan and implement occupation-based interventions

As this step in the OT process is reached, it is now time to select the interventions, as described in the OTIPM. The four models suggested include: the restorative occupation model, the acquisitional occupation model (Fig. 21-7), the adaptive occupation model (Fig. 21-8), and the occupation-based educational programs (Fig. 21-9).

Figure 21-7 Acquisitional and restorative occupation.

(From Fisher AG: Occupational therapy intervention process model, Fort Collins, CO, 2009, Three Star Press.)

Figure 21-8 Adaptive occupation.

(From Fisher AG: Occupational therapy intervention process model, Fort Collins, CO, 2009, Three Star Press.)

Figure 21-9 Occupation-based educational programs.

(From Fisher AG: Occupational therapy intervention process model, Fort Collins, CO, 2009, Three Star Press.)

Together with Astrid, the team discussed how to prioritize the goals and with which goal to start the intervention. Before each intervention session, the occupational therapist observed the client doing each of the prioritized tasks to evaluate the resources and limitations of the performance, according to the process model in OTIPM.

Implementing occupation-based interventions

In the OTIPM, four different models of interventions are described, which all have a focus on occupation. The four models of praxis are: (1) Adaptive Occupation to compensate for decreased occupational skill; (2) Acquisitional Occupation to reacquire, develop, or maintain occupational skill; (3) Restorative Occupation to restore, develop, or maintain person factors or body functions; and (4) Occupation-Based Educational Programs focused on performance of daily life tasks. Astrid’s occupational therapist used three of the models, and the plan in each area is described below:

Intervention Plan

After reading through the notes that she had taken so far, the occupational therapist, together with Astrid, reached the conclusion that they would start by making adjustments to the wheelchair that was far too high for Astrid to propel herself effectively. This had consistently been the biggest struggle for her in all observed tasks and was a prerequisite to reach her goals. Therefore, the occupational therapist chose the model of adaptive compensation at this stage.

Adaptive occupation

Wheelchair.

The occupational therapist arranged for Astrid to change her seat cushion to one that was not so thick, which meant that Astrid was immediately able to propel herself forward both effectively and quickly by using her feet. After trying this cushion for a few days, Astrid still wanted to change back to the higher cushion. The occupational therapist then tried to find a wheelchair that had a lower seat, but was not successful. At the same time, Astrid made progress with the physiotherapist and started to be able to walk with a rolling walker and an assistant. Since the occupational therapist wanted to take this into account, she thought through Astrid’s situation once again (through all the steps in OTIPM) and reached the conclusion that Astrid might be able to use a rolling work chair, with a brake and adjustable height seat, for her to use at home instead of a wheelchair (see Fig. 21-6). This chair would make reaching easier for Astrid, since she also had difficulty reaching up to the fridge and upper cupboards. It was still hard to imagine how safely Astrid would learn to walk in the future, so for the time being, Astrid could have this chair on loan. Astrid thought that this was a good idea, and the occupational therapist ordered the chair from the technical aides department. When she received the chair, it needed to be adjusted to fit Astrid, and she needed training in how to maneuver and use it in a safe manner (i.e., locking the brakes before sitting down onto the chair, before standing up, or raising it to the highest level [maximum seat height 75 cm]). After this initial practice, she also needed supervision in how to use it in the tasks that she had prioritized (i.e., making warm oats, making coffee for her friends, or making a sandwich). Simultaneously the staff at her living complex received supervision from the occupational therapist on how to support Astrid when she used the chair, how to tend to the chair, and how to use it in a safe manner.

Goal: to make a sandwich

Assistive devices/domestic technical aides.

During the observation of Astrid when she prepared a sandwich, it became clear that she had problems gripping the sandwich in an effective way; the sandwich was close to falling off the table into her lap, and it slid over the table while she was spreading the butter. Astrid tried a nonslip mat used to hold the bread in the same place as she spread the butter. She was very satisfied after she had tried it. With this mat under her sandwich, she could safely spread butter. After this purchase, Astrid practiced with the occupational therapist a few times, and within two weeks, Astrid could make her own sandwich with presliced cheese and cucumber for her afternoon snack at the day rehab.

After this goal was met, the occupational therapist and Astrid continued working on the next goal (to make coffee and cookies for her friends and make cooked oats). To reach these goals, the occupational therapist reasoned that she would need to use two different models. She decided to use the compensatory model and the model for education and teaching.

Goals: make coffee and cookies for her friends and make cooked oats for breakfast

Environmental adaptation.

Since it is not possible to carry out all of the rehabilitation initiated at the geriatric day rehabilitation in the clients home, the occupational therapist, together with the client, will adapt the kitchen in the clinic to be as similar to the client’s home as possible (i.e., the objects needed in the different tasks were placed in a way to imitate the situation in Astrid’s home). This was possible to accomplish after the home visit that the occupational therapist had done earlier and became aware of how Astrid had her home organized. While the rehabilitation sessions mostly took place at the clinic, the occupational therapist had a few opportunities during the rehabilitation period to evaluate the progress in Astrid’s home. In Astrid’s home, it became obvious that Astrid needed to reorganize some of the kitchen cupboards to enhance her ability to reach the objects she wanted to use more frequently (either as she was using the wheelchair or the work chair). In both the clinic and Astrid’s home, there was limited ability to adapt all; for example, the coffee maker was not possible to move at both locations, since it must be close to an electric outlet and to the sink.

Occupation-based education program

The occupational therapist continued to reason in relation to the results from the AMPS observation. Since Astrid had process skill ability at 0.45 logits, which indicates a need for assistance, the occupational therapist considered her need for help to safely make coffee (decreased ability to reach, place, use, handle, organize, accommodate, adjust) by educating the staff in how to best support Astrid without doing the task for her. The occupational therapist informed the staff that it is important that Astrid performs as many actions as possible by herself in each task. At the same time, the staff would need watch over and intervene in case of safety risks. The occupational therapist thus used educational principles.

Acquisitional occupation

After some time in the day rehabilitation program, Astrid had reached her first goals, and they now started to work on goals 4 and 5. To reach these goals, the occupational therapist chose the acquisitional model, which is used for occupational skills training.

Goal: to eat with knife and fork again.

Initially the occupational therapist simulated the task of eating with knife and fork using a slice of bread to imitate a thin slice of beef, and Astrid tried to cut it up using the cutlery and then eat it. They practiced this situation once every time they met for two weeks. When Astrid mastered this simulated task, the occupational therapist went to Astrid’s home to observe her during a meal. The staff at her living complex let Astrid cut her own food herself in order for her to practice in a natural (ecologically relevant) condition.

Goal: to write with her right hand.

Astrid had some remaining aphasia and apraxia and had a hard time writing spontaneously, which was revealed already as the occupational therapist observed her. The occupational therapist started with simple writing exercises, like writing a word to describe a picture. Astrid also wanted to have homework that she could do in between the times at the clinic. Initially during the practice, Astrid had a hard time holding the pen, and the occupational therapist had to place it in her hand for her to be able to use it. Maria gave her simple crosswords to solve at home. As soon as she could hold the pen herself, it was also easier for her to write. First she used block letters, and after about three weeks of training, she was able to write script again with some effort. While she was able to manage to copy text or solve a simple crossword, it was not possible for Astrid to write spontaneously, due to her aphasia.

Reevaluate for enhanced and satisfying occupational performance

The next section will describe the change in occupational performance for some of the goals that Astrid had set together with the occupational therapist.

Baseline: make a portion of hot oatmeal independently.

Astrid needed both verbal support in finding the salt and holding the pan to serve the oats and physical assistance to open the jam jar when she made cooked oats. Her performance was moderately ineffective, and she performed the task with moderate effort and needed supervision.

Astrid will, with verbal support from the staff at her living complex, initiate and, in an effective and safe way, make herself a portion of warm oatmeal using an adapted work chair.

Baseline: make an open-faced sandwich independently.

Astrid managed to make a sandwich with presliced cheese and cucumber if the objects were located within reach for her in the chair. It was with great effort that she could transport herself and place herself appropriately in relation to the actions required for the task. The task took a long time for her to accomplish, and she was moderately ineffective.

Astrid will independently and efficiently make her own sandwich with one spread (i.e., easy spread butter), sliced cheese, and presliced vegetable, using a nonslip device and a rolling work chair.

Reevaluation using the amps

As the goals that Astrid set together with Maria, the occupational therapist, have been reached, it is important to notice the changes that have occurred and to document these changes. To do so, both formal standardized evaluations of performance and of the client’s satisfaction with the results can be used. Since Maria used the AMPS initially to observe and evaluate the performance skills initially, it is appropriate to use the AMPS at the end of the treatment period to find out if ability has increased during the rehabilitation period.

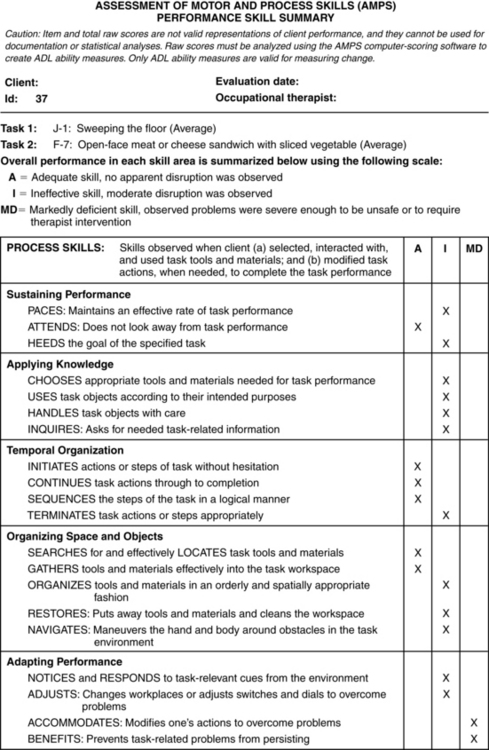

Five days before Astrid was discharged, Maria completed a new AMPS evaluation. Astrid chose the same tasks that she performed at the first evaluation: sweeping the floor and making a sandwich with cheese and a vegetable. The AMPS summary report showed the scoring of the motor and process skills for the two observed tasks and documents if the performance was adequate, ineffective, or markedly deficient (Figs. 21-10 and 21-11). The AMPS graphic report showed a significant change in her motor skills, from 0.01 logits to 0.84 logits. No significant change was noted on process skills. See the graphic report in Fig. 21-12.

Figure 21-12 AMPS graphic report for Astrid at discharge. The numbers on the activities of daily living (ADL) motor and ADL process scales are units of ADL ability (logits). The results are reported as ADL motor and ADL process measures plotted in relation to the AMPS scale cutoffs. Measures below the cutoffs indicate that there was diminished quality or effectiveness of performance of instrumental and/or personal ADL. See the AMPS Narrative Report for further information regarding the interpretation of a single AMPS evaluation.

Astrid reached all her goals according to the plan and was discharged knowing she would be able to manage the tasks she wanted with the support from the staff at her living complex.

Geriatric day rehabilitation: client living at home

In the second case, the focus will be on the day rehabilitation services for the client, August. Initially some background will be given.

Acute

August, 66-years-old, woke up in the morning four months ago with a left-sided hemiparesis. CT showed “demarked ischemic areas on the right side temporal and frontal in the basal ganglia.” He was admitted as an inpatient to the hospital’s stroke unit. During the stay at the hospital, August suffered from fatigue and memory impairments. After inpatient rehabilitation, he was able to walk with the support of two persons and needed help with personal ADL.

Subacute

After the acute phase of the stroke, he was moved to a geriatric stroke rehabilitation ward two weeks after his stroke and met an occupational therapist the same day. Together the occupational therapist and August set the goals for the rehabilitation, and those goals were:

Six weeks later August was discharged, having met his goals. August was also able to walk independently with a rolling walker. August was discharged to his home, and was placed on a waiting list for continuous training at the geriatric day rehabilitation unit.

In the beginning of the following year, about four months after his stroke, August started at the geriatric day rehabilitation unit. At his first visit, he met the occupational therapist, Maria, who conducted an interview with him. She had prepared herself by reading the referral and earlier patient files from when he was an inpatient. Maria worked with the OTIPM as her frame of reference, which guided her work as an occupational therapist. At this first meeting, August informed her about his illness and described a typical day for him at this stage. The occupational therapist listened for the daily life tasks that he described as problematic, and she asked him several questions to clarify his strengths and problems in ADL. After their meeting, to get a clear picture of August and his circumstances and concerns, she documented the key information she collected from the patient files, according to the ten dimensions described in the OTIPM. As August became a day patient at the geriatric day rehabilitation unit, he met with all the professionals in the team to establish the focus of the rehabilitation at the time. The team worked interdisciplinary, as suggested in the literature, in order to deliver quality geriatric care.10 To work interdisciplinary means that the patient is a natural member of the team, and the patient’s goals are formulated as common team goals for the rehabilitation of the patient. The needs of the patient dictate which members of the team will be involved and participate in the rehabilitation of the patient. The members of the team can shift during the rehabilitation process. The occupational therapist on the team will use the patient’s prioritized tasks as her focus during rehabilitation.

Beginning of the occupational therapy intervention process model

Establish client-centered performance context

When his occupational therapist, Maria, began the intervention process with August, she first met him for an interview to find out August’s current situation/status and his goals for the future. During this interview, the client and the therapist also developed a therapeutic rapport and a collaborative relationship. The information that the therapist gathered during this first meeting were used to identify and prioritize strengths and problems with occupational performance, and hindrances and resources in the client-centered performance context that supported and limited his occupational performance. Some information was also “stored” for use later in the process, especially information about resources and limitations within the client-centered performance context. She learned the following information as she established a global picture of the client-centered performance context.

Environmental dimension

August lives with his wife and dog in a house with three bedrooms, kitchen, and living room, in a farming village outside the main city in northern Sweden. They have three adult children and two grandchildren. Their house is on one level; the toilet has a raised seat with armrests, and the shower has a shower stool. There are no thresholds in the house, but there is a small level change (one step is 45 cm) at the main entrance, where August usually enters the house. He has received supportive railings on both sides of the entrance to manage the different levels.

There is a home office with a computer, office chair (no brakes), and a telephone. He manages most of his company’s bookkeeping in this office. He can manage the office chair safely. It is hard for him to manage the telephone with his left hand, but he can manage the computer with his right hand. His house is located nearby the forest, and there are a bicycle and a car parked in front of the house.

Social dimension

August’s wife is supportive, and she and August seem to have a good relationship. The three children are also available in times of need. August also has many friends and relatives that he frequently visits during his leisure time.

Role dimension

August and his wife have a traditional, Swedish role distribution in the home (i.e., August takes care of the maintenance of the house and the outdoors, and his wife is responsible for the domestic care). August’s role is to maintain the outside of their house. During winter, that means snow shoveling, but now he gets help with snow-clearance from a neighbor. August would like to manage this independently. In the summer, maintaining the house means mowing the lawn, which August would like to manage by himself. August will prepare simple ready-made food and also makes “fika” (coffee and cookies), while his wife cooks food from scratch.

Before his stroke, August worked in his own company together with his wife. His main tasks were bookkeeping. He is worried about what will happen to the company in the future, and if he will be able to manage as before.

August identifies himself as a traditional man in the village where he lives (i.e., as a hunter and fisherman, and “knowledgeable in most things”). He also worries about being able to hunt again or taking the dogs for walks in the forest. Currently he cannot perform these tasks.

Cultural dimension

August lives in a farmer village where “everybody knows everybody else.” He shares the customs, habits, values, and beliefs with the other people in the area, a traditional village in the north of Sweden. August had a hard time initially as he was not able to manage his “typical male” tasks in the home: snow clearance, walking the dog, driving the car/motorbike, and mowing the lawn.

Motivational dimension

In his leisure time, August spends a lot of time in nature, mainly hunting and fishing. He hunts mainly for moose and small game. This is something that he enjoys, and he would like to regain this ability. He was also responsible, together with a friend, for managing the local shooting range. He hopes to be able to continue this during the upcoming hunting season. August used to make daily walks together with his hunting dog, walking in the forest or biking, and he wants to pursue this again. He is also interested in motors and has his own motorbike and has enjoyed ballroom dancing.

Institutional dimension

August’s wife supports him, and he has no demands from society to go back to work since he had planned to retire during this year. He has the whole team at the day rehabilitation unit supporting him for the time during his rehabilitation. There are no medical restrictions related to August’s impairments that limit him from doing the tasks that he has done before.

Body function dimension

August survived a right-sided stroke about four months ago. He has a weakness in both left hand/arm and leg, but can walk safely and independently with a rolling walker. August feels depressed and has a hard time sleeping at night. He is easily fatigued.

Task dimension

August describes his biggest problems, which are his highest priorities. He wants to manage to hold a telephone receiver with left hand at the same time as he makes notes with his right hand. He also wants to hold his hunting weapon in a correct way, and hopefully later he would like to continue to hunt. He also mentions wanting to hold a potato on the fork with one hand and peel it with the knife in the other hand. Another task that he wishes to do is walking the dog. For him to do this, he needs to be able to walk safely with a walking stick and manage to lead the dog on a leash without the dog pulling him. Due to his decreased balance and gait, this is currently not possible.

Temporal dimension

A usual day in August’s life right now is that he rises up early in the morning, completes his bathroom routine, gets dressed, eats breakfast, and reads the daily newspaper. He then exercises for one hour, eats another small snack in midmorning, and then takes a rest and watches TV. He has a coffee midday and exercises for another half hour. Afterwards he cooks/warms dinner and watches TV in the evening. He goes to bed around 10:00 pm.

August lives at home during the outpatient rehabilitation and goes by taxi the 30 km into town two mornings a week between 9:00 and 11:30 am. This will continue until he meets the rehabilitation goals documented together with the team, in about two to four months. August has progressed well during his rehabilitation mainly because he is motivated and is in otherwise very good physical condition.

Adaptation dimension

August has the ability to adjust to his current circumstances and takes in instructions for exercise/training and continues the training at home by himself in between the rehabilitation visits.

He uses his wife and friends to increase his activity repertoire in his everyday life and makes sure that he can try to regain activities/tasks that he has done earlier himself (i.e., walking the dog and mending inventories at the shooting range).

Develop therapeutic rapport and collaborative relationships

August was motivated for the continuous rehabilitation and positive that he would be able to practice more at the rehabilitation unit. He told the occupational therapist, Maria, how he managed during the days at home and reviewed areas of difficulty. Maria listened carefully and asked follow-up questions as needed, so that she would get a complete picture of August’s performance context. They both felt they had a nice therapeutic relation after this conversation.

Identify and prioritize reported strengths and problems of occupational performance

After the collection of information on the ten dimensions needed to establish the client-centered performance context, the occupational therapist needs to summarize the information. As the OTIPM is followed, two parts are documented: (1) resources and limitations within the client-centered performance context, and (2) self-reported strengths and problems of occupational performance.

The documentation at this stage is described below.

Background information: August is 66-years-old and lives in a village outside a major city with his wife. They run a company together. August is responsible for the bookkeeping. The rehabilitation starts by the team developing a rehabilitation plan together. August’s main interests are hunting, caring for his dog, and being outside in the forest. August expresses problems using his left hand the way he wants to (i.e., holding his hunting rifle), and his weak left leg interferes with performing his other interests.

Reason for initial referral: August was referred to day rehabilitation unit in the geriatric department for interdisciplinary team rehabilitation. August will meet with Maria, the occupational therapist, for evaluation and intervention.

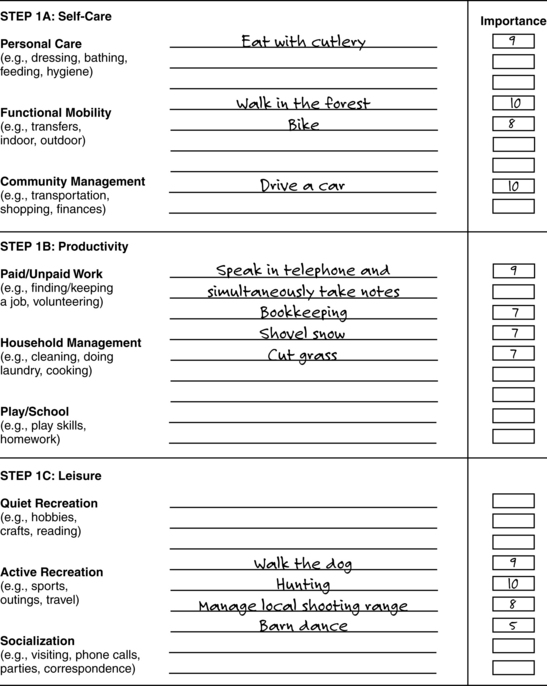

The first part is to identify the resources and limitations within this client’s performance context, and how the limitations hinder the client’s engagement in his life roles. From the list of tasks discussed, the client prioritizes which he finds to be most important. The performance of tasks that support the clients engagement in life roles are the strengths, while those tasks that the client experience as problems to perform and that hinder the engagement in life roles are limitations. At this stage, it might be appropriate to use another instrument to verbalize the strengths and limitations and to prioritize them. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)7 is a tool that can be used, since it will clarify and describe the strengths and limitations of the client. Maria administered the COPM at the beginning of the rehabilitation period. The COPM helped Maria and August priorities for intervention. See August’s COPM results in Fig. 21-13.

Figure 21-13 Results from August’s interview using step 1 of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure.

(Modified from Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al: Canadian occupational performance measure, Toronto, Ontorio 1994, CAOT Publications ACE.)

August also put priority on driving again, but in Sweden there is a common rule that each person who has a stroke is not allowed to drive during the first six months after the stroke.

Identified Level of Performance:

August manages his morning routines and simple domestic chores independently, although he cannot manage peeling his potatoes at mealtime since he cannot grasp the fork in his left hand.* He has problems talking on the phone and simultaneously taking notes, which he needs to do to run his company. August is unable to walk his dog in the forest, which was his duty earlier. He also reports that he is not able to attend to his house and garden chores in a safe manner, due to his limited balance and limited grip with his left hand. He also wants to be able to hold his rifle in a correct way and, if possible, also hunt during the fall again.

Being able to eat with both cutlery again (knife and fork)

Being able to eat with both cutlery again (knife and fork)

Talk in the telephone and simultaneously take notes

Talk in the telephone and simultaneously take notes

* In Swedish culture, it is common for each person to peel boiled potatoes by holding the potato in the air, supported on a fork held in one hand, while the person simultaneously removes the peel using a knife held in the other hand (Fig. 21-14).

Observe client’s task performance and implement performance analysis

As the OTIPM is followed, it is time for Maria to observe August doing some of the tasks that he identified as being problematic for him. This first performance analysis will give Maria the opportunity to evaluate the quality of the client’s performance when executing a chosen task. Maria planned to use a standardized instrument to evaluate August’s performance, and she decided to use the AMPS, for her performance analysis. Since the tasks that August had problems performing were not available as task choices in the AMPS, she did the observation with her “AMPS eyes” and could thus describe his performance using the AMPS vocabulary, but she was not able to enter the information into the AMPS software. The information was still very valuable and helped her in her documentation of August’s performance.

Make a phone call and take notes.

In August’s case, the occupational therapist wanted to observe the client perform some daily tasks that he experienced difficulties performing and that he had prioritized. August chose to start by showing how he used the telephone. The observation was carried out at the OT department, using the telephone of the occupational therapist. It became obvious that August was not able to hold the receiver in an effective manner, as it slid out of his hand. He was not able to hold it long enough, so that he would be able to make notes at the same time with the pen in his right hand.

After the observation, Maria and August discussed how he had experienced the task, and the occupational therapist told him what she had observed as his strengths and limitations during his performance. Maria also suggested that he could do the task by leaning the elbow on the table, but August expressed a need to do the task without elbow support.

Peel boiled potatoes with knife and fork.

At the third observation, August performed the task of peeling a boiled potato on a plate in front of him at the kitchen table. He sat on a chair by the table and had the plate with potatoes in front of him, with cutlery on the side of the plate (fork to the right and knife to the left of the plate). It was hard for August to turn his left hand in an effective manner to put the fork into the potatoes. As he pierced the potato on the fork, he had difficulty holding it to peel the skin off with the knife in his right hand. His arm was unsteady, and he was not able to hold the position for the amount of time needed to peel the whole potato. He managed slightly better when he leaned his left lower arm on the table, but still did not have an effective performance.

Define and describe actions the client does and does not perform effectively

The occupational therapist made a note in the patient file about the observed and measured baseline.

Baseline: August managed to perform the task “making a phone call” with a mild degree of effort (the grip on the receiver), a modest degree of disorganization, and an undesirable use of time (he lost his grip and needed to use his right hand instead), which resulted in the inability to make notes at the same time as he spoke on the phone.

Grouping skills of most concern into meaningful clusters.

August’s limitations can be summarized into the following clusters:

Cluster 1: positions and coordinates.

August needs to place the arm in a position that facilitates continuation of the task and coordinate both limbs. August has limited ability to hold the arm in the needed position long enough to make notes with his right hand.

Cluster 2: grips, manipulates with his left hand, and lifts.

August has a limitation in holding the fork in his left hand in a position to facilitate peeling with the knife in the right hand.

Cluster 3: attends and organizes.

August showed limitations in listening to the conversation on the telephone at the same time as he took notes. The limitation was increased as the pen and paper were placed too far away at the desk

Cluster 4: paces, heeds, chooses, continues, and sequences.

August also had strengths. August shows a nice pace as he performs the tasks, and he also works toward completion of the task. He chooses the tools and materials, and works continuously without interruption and completes both tasks in an orderly sequence.

Initial evaluation

Baseline: observed.

When Maria, the occupational therapist, has summarized the strengths and limitations, she continues to document August’s baseline, both the global baseline and the specific baseline. Both these baselines will be documented in the patient files and will be used as the base as the team plans the rehabilitation, including setting the goals with August.

Global baseline: making phone call.

The occupational therapist documented in the files the observed and measurable global baseline: August managed the task of making a phone call with mild degree of effort and was moderately effective, which limited him to make the notes at the same time.

Specific baseline: making phone call.

August had the pens far away from his sitting position, which made him have to reach far to pick one up in order to make notes. This provided some limitation since he had trouble holding the receiver with his left hand at the same time. He had limited ability to grip and coordinate. He was also limited in attending to the task of talking in the phone, since he needed to concentrate on holding the receiver in his left hand and simultaneously making notes with his right hand. August was ineffective in accommodating his actions and his work area.

Global baseline: peeling potato.

August performed the task of peeling the potatoes using cutlery with moderate effort and a mild degree of disorganization.

Specific baseline: peeling potato.

August had problems manipulating the fork in a necessary way with his left hand, which resulted in limitations in the ability to pierce the fork into the potato and position it for ease of peeling with the knife in the right hand. His elbow was angled out from the body as he performed the task. He hesitated before he accommodated by putting the arm onto the table for support.

In the same manner, Maria evaluated the other highly prioritized tasks: to shoot with a hunting rifle and to walk the dog. These observations were made at a shooting range and at home as he walked his dog.

Define/clarify or interpret the cause.

When Maria had evaluated the quality of her client’s performance, she continued to clarify or interpret the cause of the limitations observed. This can be done by taking into account all information collected during the establishment of the client-centered performance context, by thinking about that the observations made on the client’s performance, and by administering other evaluations through interviews and nonstandardized or standardized evaluations. To underscore the unique focus in OT on activity and participation, activity and participation must be documented.

When Maria looked through her notes from the ten dimensions, she saw that August’s problem was mainly related to his hemiparetic left arm and leg. Maria also noted that August had a swollen left hand, increased spasticity, and decreased coordination in the elbow and hand. This influenced his occupational performance and primarily the fine motor aspects of the performance. Due to his left-sided weakness, he also had problems with balance; however, Maria did not need to investigate that further, since she had information from the interdisciplinary team members to confirm these observations. During the team conference held once a week, the whole team received a very thorough picture of the client, as all members of the team presented their results of evaluations and tests to the other team members.

Initial occupational therapy evaluation and interpretation of cause

Decreased motor function in the left side, increased tone, and decreased balance influenced how August performed his prioritized daily tasks. Decreased fine motor control, a swollen hand, and decreased strength in his left hand had disrupted his ability to grip and manipulate objects. Attending to two things simultaneously was also limited. The decreased balance and muscle weakness in his leg affected his ability to walk in the forest and walk the dog.

Document client’s baseline and goals

The interdisciplinary team met with August to plan and set goals to reach during the rehabilitation period. Maria brought her notes of the global and specific baselines, and together they set the following goals:

To eat a meal using both knife and fork without effort and in an efficient manner

To eat a meal using both knife and fork without effort and in an efficient manner

To talk on the phone and make simultaneous notes effectively and with minimal effort

To talk on the phone and make simultaneous notes effectively and with minimal effort

Maria needed to select an intervention model, and plan and implement occupation-based interventions. Each member of the team worked according to his or her specific focus and towards those goals. For example, the physiotherapist worked with training of underlying body functions (i.e., increase balance, muscle strength, endurance, fine motor) to strengthen August’s body, so that he could meet his goals. The occupational therapist continued her process in line with OTIPM and now the time had come to choose a model for intervention that would cover the goals and focus on occupations.

Occupation-based interventions in instrumental activities of daily life

Intervention Plan

Acquisitional occupation: making phone calls, eating with cutlery

Adaptive occupation: using the air gun (available in OT department), sitting at a table with support under arm, taking the dog for a walk, and doing “Nordic walking” with poles with supervision from wife

Restorative occupation: introduced to a program to practice training with affected hand using therapeutic putty at home. Received a glove for compression of hand to prevent edema of the hand