chapter 25 Sexual function and intimacy

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following:

1. Identify and describe the normal human sexual response cycle and the changes that occur during the aging process.

2. Understand the effects of stroke on sexual function.

3. Identify the occupational therapist’s role in sexuality intervention.

4. Understand and apply the levels of the PLISSIT model that are appropriate for occupational therapists.

5. Identify sexual impairments and how they affect function.

6. Plan treatment interventions for impairments affecting sexual function.

A discussion of sexuality includes not only specific sexual practices but also the attitudes, behaviors, thoughts, and feelings associated with sex and sexuality. These include an individual’s perception of self as a sexual being, body image, self-esteem, participation and roles in relationships (sexual and other), sexual orientation, and beliefs and attitudes toward a wide range of sexual behaviors, including masturbation, coitus, oral-genital sex, cuddling, and sensuality. Romano66 defined sexuality expertly: “Sexuality is more than the art of sexual intercourse. It involves for most . . . the whole business of relating to another person; the tenderness, the desire to give as well as take, the compliments, casual caresses, reciprocal concerns, tolerance, the forms of communication that both include and go beyond words . . . sexuality includes a range of behavior from smiling through orgasm; it is not just what happens between two people in bed.”

Everyone can enjoy sex. Health care professionals must be aware of their own attitudes toward sexuality. Our patients may be different from ourselves: they may be older, may be of a different sexual orientation, or may have permanent or temporary disabilities. Just as differences among human beings are inherent, therapists must consider and respect the variances in sexual behaviors, preferences, and beliefs among individuals.

Normal human sexual response

One must have an understanding of the normal human sexual response cycle before one can explore the relationship between sexuality and disability. Masters and Johnson48 divided the human sexual response cycle into four segments: (1) excitement, (2) plateau, (3) orgasm, and (4) resolution. In each phase, definite physical changes occur in both sexes. During the excitement phase, physiological reactions occur because of somatosensory or psychogenic stimulation. In females, the nipples become erect, the vagina swells and becomes lubricated, the clitoris and the labia minora and majora swell, and the uterus and cervix retract. In males, the penis grows erect and the testes rise. In both sexes, blood pressure and heart rate increase.

During the plateau phase, respiration increases and blood pressure and heart rate escalate further. In females, the areola surrounding the nipple swells, the orgasmic platform forms (vasocongestion of the outer two thirds of the vagina), and the color of the labia minora deepens from pink to red. In males, a full erection is achieved as the testes elevate further and the Cowper gland secretes preejaculatory fluid.

Orgasms differ between the sexes; some women can achieve multiple orgasms. In both sexes, peak pulse rate, blood pressure, and respiration increase, as does muscle tone. Rhythmic contractions of the orgasmic platform and the uterus occur in women, and rhythmic contractions of the penis project semen forward in males.

Masters and Johnson48 recorded cardiac response and found peak heart rates of 110 to 180 beats per minute during orgasm. However, the mean maximum heart rate during sexual activity was 117.4 beats per minute in a study of middle-aged men with postcoronary disease.34 During sexual activity, systolic and diastolic pressure increase (from 30 to 80 and 20 to 40 mm Hg, respectively). Respiration rates of up to 40 breaths per minute have been recorded, depending on the level of intensity and duration of sexual activity.48

The resolution phase is characterized by the return to preexcitement status, including reductions in blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration. The genitals and breasts return to preexcitement size.

Aging and the human sexual response cycle

In normal human development, changes occur during the aging process. Such changes affect sexuality61 in males and females and already may affect patients who have sustained cerebrovascular accidents.

Women

Generally women experience menopause between the ages of 40- and 50-years old; the cessation of menstruation is caused by a lack of production of estrogen that occurs over a period of several months to a few years.43 The major effects of menopause are as follows:

Vasomotor syndrome (hot flashes)43

Vasomotor syndrome (hot flashes)43

Atrophic vaginitis (thinning of the vaginal walls)43

Atrophic vaginitis (thinning of the vaginal walls)43

Osteoporosis43

Osteoporosis43

A decrease in the rate, amount, and type of vaginal fluid, which can cause pain during intercourse and may lead to infection74

A decrease in the rate, amount, and type of vaginal fluid, which can cause pain during intercourse and may lead to infection74

Loss of contractility of vaginal muscles, which can cause shorter orgasms74

Loss of contractility of vaginal muscles, which can cause shorter orgasms74

Decreased size of the uterus and clitoris and atrophy of the clitoral hood43

Decreased size of the uterus and clitoris and atrophy of the clitoral hood43

According to Laflin,43 regular muscle contractions help maintain the integrity of vaginal muscle tone, and “contact with the penis helps preserve the shape and size of the vaginal space.” Therefore, an active sex life can have a positive effect on genital function.

Men

As men grow older, the following changes occur:

Erections are often less full, take longer to achieve, and may require direct stimulation.74

Erections are often less full, take longer to achieve, and may require direct stimulation.74

Ejaculatory control increases, ejaculation may only occur every third sexual episode and is less forceful, and loss of erection after orgasm may occur faster.43,74

Ejaculatory control increases, ejaculation may only occur every third sexual episode and is less forceful, and loss of erection after orgasm may occur faster.43,74

The man may not be able to achieve another erection for 12 to 24 hours after orgasm.39

The man may not be able to achieve another erection for 12 to 24 hours after orgasm.39

Sperm volume decreases and the ejaculation may be less intense, which may affect the intensity of orgasm.43,74

Sperm volume decreases and the ejaculation may be less intense, which may affect the intensity of orgasm.43,74

Many elderly persons continue to enjoy sexual activity; however, a decline in sexual activity among elderly persons is common. Older persons do not necessarily lose their desire for sex, but circumstances can make it difficult for them to engage in active sexual relationships. Leading causes of altered sexual activity in the older adult include difficulty finding partners, illness, medication effects, widowhood, divorce, biases about masturbation, societal attitudes about sex and the elderly, and even their own biases and prejudices toward sexuality.65 Elderly persons may view sex as something that only young, attractive persons do.

Sexuality and neurological function

Sexual function is controlled by the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves, whereas control of libido and sexual pleasure are mediated by several areas in the cortex, midbrain, and brainstem.56 Men experience reflexogenic and psychogenic erections. Reflexogenic erections are caused by direct stimulation to the penis and may occur without conscious awareness, even in the absence of penile sensation. Psychogenic erections originate from mental activity such as sexual fantasies and stimulating visual input and do not require direct penile stimulation. Reflexogenic erections are controlled by the nervous system through the sacral roots, and psychogenic erections involve the sympathetic nerves between T11 and L2. Female sexual function is similar to that of males regarding nerve innervation.77 The parasympathetic nerves S2 to S4 influence the clitoris and vaginal lubrication. “Contraction of the vaginal sphincter and pelvic floor occur with stimulation of the somatic aspect of the pudendal nerves (S2-S4),” according to Zasler.77 Neurological disability can cause organic impotence by altering the blood flow needed for penile erection and can cause problems with emission and ejaculation in males and with lubrication, clitoral engorgement, and orgasm in females. Some of the subcortical structures theorized to be involved in the neurology of sexuality are the reticular activating system and the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus. According to Zasler,77 the thalamus and basal ganglia are hypothesized to be involved with the mediation of sexual function. Some of the cortical areas involved are the frontal lobes and the nondominant temporal lobe. “Lesions in the dominant hemisphere may produce aphasia or apraxia, both of which could impede sexual activity. Nondominant hemisphere injury may result in . . . visuoperceptual deficits, denial, and impulsiveness, all of which could impede expression of sexuality,” according to Zasler.77 Sexual stimulation is caused by stimulation of the brain or peripheral nerves, the former of which results from thoughts and psychological processes and the latter of which results from direct physical stimulation.54,72

Effects of stroke on sexual function

The literature shows that common effects of stroke on sexual function are decreased libido, impaired erectile and ejaculatory function, decreased vaginal lubrication, impaired ego and self-esteem, and depression. The motor, sensory, cognitive, and physiological effects of stroke have been shown to affect the desire and ability to engage in sexual activities in many ways. Some research has been focused on relating sexual dysfunction to the location of the lesion. Some of the scientific literature recommends counseling for patients following stroke but does not provide specific interventions.* As a result, therapists are left with insufficient information to treat sexual dysfunction adequately.

Numerous studies have found that among men and women who had sustained strokes, libido was decreased, abilities to achieve erection and vaginal lubrication were impaired, and the frequency of intercourse was diminished.11,38,40,41,53,73 In contrast, at least one study documented that a small group of stroke survivors (19 of 192 patients studied) indicated an increase in libido following stroke.41 Isolated cases of hypersexuality and abnormal sexual behavior have been found to occur in individuals with temporal lobe lesions and concurrent histories of poststroke seizure activity.28,54 In a study of 13 female stroke survivors, the most common complaint was found to be a decreased desire for sexual activity after the stroke; only 5% of the women reported actual impairment in the production of vaginal secretions after the stroke.2 Most of the women reported no changes in their abilities to achieve orgasm or in their menstrual periods. In addition, although the stroke impaired sexual desire, physiological function remained unimpaired. The authors concluded that nondominant hemispheric stroke is related to decreased desire; five of seven patients with decreased desire had right brain involvement.

The authors of several studies have attempted to determine cerebral hemisphere dominance related to sexual function. Although some investigators found a greater decline in sexual function with left-sided cerebrovascular accident, others found little or no difference between right and left cerebral hemisphere strokes.* One study of 109 men poststroke revealed that lesions in the right hemisphere resulted in a significant decline in sexuality functioning poststroke, including desire and frequency.36 Garden25 concluded, “There seems to be an overall consensus that stroke patients maintain prestroke sexual desire but commonly experience sexual dysfunction including erectile and libido problems. Changes in coital frequency and libido are also common. As a result there can be great potential for depression and loss of self esteem.”

The individual’s prestroke sexual activity is usually a better indicator of poststroke activity.7,26,29,33,42,73 If the individual was leading an active sex life before a stroke, the likelihood of returning to sexual activities is good. Younger age is also a predictor of resumption of sexual activity, although less so.33 Individuals who were without a partner before a stroke have less opportunity to develop new partnerships and resume sexual activity after a stroke. This decreased opportunity has to do with the effects of stroke itself and an individual’s impaired social contact, possible placement in a nursing home or other long-term setting, depression, altered self-image, and the multitude of psychological effects caused by stroke. In a study of 192 stroke survivors and 94 spouses, the decline in sexual activity after stroke was associated largely with individuals’ attitude toward sexuality, fears including erectile dysfunction, and the inability to discuss sexuality issues.41

Erectile dysfunction may occur as a direct result of stroke* and also may occur in men whose sexual partners have sustained strokes because of fear of causing another stroke or hurting the partner or averse feelings toward the disabled partner.26,28,29,30 In women, vaginal lubrication may be insufficient, causing painful intercourse.2,11,25,26,40,73

The presence of nocturnal erections indicates psychological versus organic reasons for erectile dysfunction. In a study by Korpelainen, Nieminen, and Myllyla,41 all of the male subjects did experience nocturnal erections after stroke, although 55% had impaired nocturnal erections. Individuals with a history of taking cardiovascular medications and those who had diabetes mellitus exhibited a greater frequency of erectile dysfunction after stroke than those without. Bener and colleagues5 found similar results in a study of 605 men following stroke; the likelihood of erectile dysfunction increased with cardiovascular medications and comorbities including hypertension, hypercholestermia, and diabetes. Similarly, impaired vaginal lubrication was more common in women who had taken cardiovascular medications prestroke.41

Initiation of sexual activity after discharge from the hospital may be difficult. A couple may delay sexual activity because each partner waits for the other to initiate sex.29,30 In a study by Goddess, Wagner, and Silverman,29 one couple put off sexual activity for 15 months after the husband’s stroke. The man was unsure whether his wife would find him attractive or a suitable partner, and the wife was concerned that sexual play for her husband may be unsafe.

Sensory impairment is common after stroke. Considering the significant role of touch in sexual expression, its dysfunction also may contribute to sexual dysfunction.24,40 In subjective reports of 50 stroke survivors, 19% of the subjects reported sensory deficits as the reason for diminished sexual activity.40 However, the research is inconclusive; a study by Aloni and colleagues1 of 15 male stroke patients showed that disturbed superficial and deep sensation were not correlated with decreased desire.

Motor impairment can affect sexual function. Decreased range of motion, strength, endurance, balance, abnormal skeletal muscle activity, impaired coordination, and oral motor dysfunction may interfere with intercourse or other sexual activities. However, some research suggests that the degree of hemiplegic impairment is not a major factor in sexual dysfunction.24,26

Cognitive deficits also may affect the stroke survivor’s social and sexual function. Fundamental cognitive abilities such as attention and concentration are prerequisites for social and sexual activities; distractibility and overstimulation may cause anxiety and agitation, which prevent interaction. Decreased initiation, impulsivity, poor memory, decreased speed of processing, and impaired executive functions are possible effects of neurological dysfunction and clearly can affect sexual relations.71

McCormick, Riffer, and Thompson51 noted that sexual activity is itself a form of human communication. When verbal or nonverbal communication is impaired, sexual activity may be affected.77 One study found that sexual adjustment was easiest for physically intact individuals with aphasia with spared comprehension and nonverbal communication.76 However, in one study involving 110 subjects, no correlation between aphasia and poststroke sexual activity was found.70 Lemieux, Cohen-Schneider, and Holzapfel44 reported that individuals with moderate and severe aphasia are not included in most studies because they are difficult to interview, so little is known about their sexuality after stroke. In their small study of aphasia and sexuality in six couples, the researchers developed pictograms to facilitate communication with aphasic respondents. Although the effects of stroke on sexuality in this study were similar to those of previous studies, almost all the aphasic persons and their partners reported that aphasia had a negative effect on their sex lives.

The effect of stroke on psychological function is enormous11,28,36,42 (see Chapter 2). Studies by Giaquinto and colleagues28 and Korpelainen and colleagues40 found that the psychological impact of stroke was a greater factor in sexual function after stroke than associated neurological deficits. The loss of function, including hemiparesis, sensory and balance disorders, pain, and cognitive, perceptual, and impaired communication skills may have an enormous negative effect on an individual’s self-image. As Strauss71 noted, the formulation of relationships, sexual or other, requires some level of self-esteem. An impaired image of one’s body and appearance can affect the ability to make new relationships or maintain existing ones. Loss of confidence and decreased self-esteem may result from the following:

Changes in appearance, including facial asymmetries and diminished facial expression

Changes in appearance, including facial asymmetries and diminished facial expression

Changes in clothing style (inability to don pantyhose or walk in high heels due to required ankle-foot orthosis)

Changes in clothing style (inability to don pantyhose or walk in high heels due to required ankle-foot orthosis)

Need for adaptive equipment or assistive devices such as a splint, wheelchair, or cane

Need for adaptive equipment or assistive devices such as a splint, wheelchair, or cane

Dependence in activities of daily living (ADL), such as the need to have food cut and to have assistance with toileting

Dependence in activities of daily living (ADL), such as the need to have food cut and to have assistance with toileting

In addition to changes in self-perception, the stroke survivor suddenly may find a new role in relationships. For instance, a wife may discover that she is no longer able to carry out the functions related to her role as wife because of the effects of a stroke. The stroke survivor may depend more on other family members. Role changes could affect the quality of an existing relationship.9,65 Such changes may be confusing and stressful for the patient and the partner, particularly if the stroke survivor requires assistance with self-care activities such as toileting or bathing. Dependence in ADL is a major predictor of decreased sexual activity level after a stroke. In a study by Kimura and colleagues,38 subjects who demonstrated ADL impairments also exhibited a decline in sexual activity. Sjogren and Fugl-Meyer reported similar findings as early as 1982.70

Impaired bladder function also may affect sexual activity. Stroke often occurs in the elderly who may have underlying genitourinary dysfunction (prostatic hypertrophy, stress incontinence). Proper evaluation by a urologist is indicated.47,62 Marinkovic and Badlani47 recommended treatment of incontinence before addressing sexual dysfunction. Medications used to treat incontinence have side effects such as dry mouth, which can make kissing or other oral activities unpleasant. If the individual takes additional medication for other reasons (for example, diuretic agents), urine output may be increased. For the individual with mobility impairments, quick and frequent access to the bathroom may be difficult, resulting in episodes of incontinence. Incontinence may affect self-esteem and may be a source of embarrassment.37 Bowel incontinence is less common after cerebrovascular accident because stroke patients typically are constipated because of immobility, inactivity, and poor food and fluid intake, which can cause bloating and discomfort.75

Hypertension is a major risk factor for stroke, and research indicates that hypertension is associated with sexual dysfunction in men and women. Burchardt and colleagues8 reported a higher incidence and greater severity of erectile dysfunction in men with hypertension compared with an age-matched population without hypertension. The study also suggested that the erectile dysfunction was linked to the hypertension and not to side effects of antihypertensive medications. Grimm and colleagues31 also found that “sexual dysfunction in hypertensive individuals may be related more to hypertension level than to drug treatment.” Hypertensive women also report decreased lubrication, less frequent orgasm, and more frequent pain with sexual activity than women without hypertension; again, the effects were not related to the type of treatment.19

Individuals who have had strokes often have a history of other medical problems, including heart disease, which alone can cause functional impairments related to sexual activities. Often individuals with a history of myocardial infarction or bypass surgery fear the resumption of sexual activities.31,45,55 Muller and colleagues55 studied 858 patients who were sexually active in the year preceding myocardial infarction and found that although the risk of myocardial infarction increases in the two hours following sexual activity, the risk is almost equivalent in patients with and without heart disease. The research indicated that the risk of myocardial infarction caused by sexual activity is two in one million for a person with heart disease and that individuals who experience periods of anger or heavy exertion have a greater increase in actual risk because these behaviors occur with more frequency than sexual activity. However, the overall risk of myocardial infarction is lower for patients who engage in regular exercise, which has been shown to decrease the amount of cardiac work required during sexual activity.

“At its peak, sexual activity is about as physically strenuous as walking two to four miles per hour. The greatest levels of ‘exertion’ actually occur during orgasm, which lasts only a brief amount of time.”67 Studies to determine cardiac expenditure are often performed on treadmills. Palmeri and colleagues60 compared cardiac response during sexual activity to treadmill testing; results indicated that the amount of “work” during sexual activity was half the maximal found on treadmill testing and that there are different physiological responses to upright (i.e., treadmill testing) versus supine activity (i.e., sexual activity). Average heart rates ranged from 108 to 128 beats per minute. From a cardiac rehabilitation perspective, a patient is “safe” to resume sexual activity when the person can climb two flights of stairs or walk the length of a city block or its equivalent at a brisk pace with no discomfort.34,45 This parameter may be difficult to assess in some stroke patients because of mobility deficits, and alternative activities may have to be explored (for example, propelling a wheelchair at a brisk pace with the use of unaffected arms and legs). The effect of stroke on sexual function is difficult to assess without examining the types of medications patients are taking. Antihypertensive agents have been found to cause erectile dysfunction, impede ejaculation, and decrease libido.10,13,23,24,26 Some β-blockers are known to affect erectile function and cause depression. One antihypertensive diuretic medication, spironolactone, is known to cause breast tenderness, galactorrhea (excessive secretion of the mammary glands), and gynecomastia (overdevelopment of the mammary glands), which is not always reversible in men.13 In a study by Aloni, Schwartz, and Ring,2 six of the seven women who reported decreased sexual desire were taking anticoagulant drugs, suggesting that the medications may affect sexual function. Medications other than those prescribed for stroke management or hypertension may have additional side effects such as rashes and feelings of fatigue that may affect a patient’s desire to participate in sexual activities. Considering the potential side effects of various medications on sexual function and informing patients as necessary is the rehabilitation team’s responsibility.

Societal attitudes

Attitudes on the part of the public or the patient’s family members also may affect the patient emotionally or psychologically. Although the Americans with Disabilities Act has resulted in some improvement in public attitude, the fact remains that many persons still harshly judge individuals who appear “different” from the rest of society and regard disabled individuals with fear and shame. Stroke survivors and persons with other disabilities perceive these attitudes and, as a result, avoid social or public situations. The media seldom depict persons with disabilities as full partners in sexual relationships. The stroke patient and partner, family members, and others may share the view that persons with disabilities are sexless, “different,” and undeserving of social and sexual fulfillment. These attitudes can affect patients’ existing relationships and their willingness to pursue new relationships.

Role of occupational therapy

When persons experience changes in sexual function, they may require professional intervention to cope with these changes in sexual function and sexuality. What is the role of occupational therapy in sexuality intervention for these patients, and what is required to fulfill this role?

Sexuality long has been considered an appropriate area for occupational therapy intervention. Andamo3 stated that “sexual function should be included in the occupational therapy evaluation as it relates to the identification of the patient’s abilities and limitations in his daily living necessary for the resumption of his various roles.” Neistadt56 noted that as “holistic caregivers, dedicated to facilitating quality lives, occupational therapists should be prepared to address sexuality issues with their adolescent and adult patients.” Couldrick15 argued that “with awareness and skill development, occupational therapists can affirm sexual identity, they can listen, and, with sometimes simple measures, they an address issues that fall within their professional roles.” The American Occupational Therapy Association has continued to confirm the role of occupational therapy by including sexual activity as an ADL within the areas of occupation in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework.59

Occupational therapists are well-prepared to address sexuality problems in stroke patients; the sensory, motor, cognitive, and psychosocial impairments that interfere with sexual function are the same ones that affect other performance areas addressed by occupational therapy, including other ADL and work and leisure activities. Occupational therapists’ skills of activity analysis and adaptation, holistic orientation, and knowledge of biological and behavioral sciences help them deal effectively with patients’ sexual difficulties.21 Research indicates that dependence in ADL is a major factor in decreased sexual activity after stroke,38,70 further supporting the role of occupational therapists in sexual rehabilitation by restoring patients to the highest possible level of independence and role function.

Most occupational therapists receive some training in sexuality intervention. Even before the American Occupational Therapy Association listed sexual activity as an ADL, the authors of a 1988 study reported that 88% of 50 occupational therapy programs included formal classroom training about sexual function, with an average of three and a half hours of class time devoted to this subject.63

Team approach

Although occupational therapists must be involved in sexual health care, effective sexual rehabilitation, like all rehabilitation, requires a team approach. The rehabilitation team must address all the individual’s problems in a holistic way, and all team members should be knowledgeable about sexual issues and treatment options.46,77 If each member of the treatment team is educated and skilled in this area, the patient can choose the team member with whom he or she is most comfortable to address sexual issues. In addition, each team member has different expertise from which the patient may benefit. The physician may best address problems related to erectile dysfunction, relationship changes may require social work intervention, and the speech and language pathologist may best address communication difficulties.

In reality, the health care team often ignores sexuality issues, especially for the stroke population. A support group of 37 wives of stroke patients at a Veterans Administration center reported that no one had spoken to them about poststroke sexuality.51 In a 1988 study of sexuality counseling in an inpatient rehabilitation program, only 20% of non–spinal cord injured patients (55% of whom had a diagnosis of stroke) had received written materials on sex. Sexuality information was given voluntarily to 32%.16 Rehabilitation professionals cite various reasons for not addressing sexuality with their patients, with the most common responses being that another team member is responsible for this intervention and that their knowledge is inadequate.51,57 In a pilot study of health care professionals who treat stroke patients, including occupational and physical therapists, lack of training and experience were cited as reasons to not address sexuality. Over half felt that they would be inhibited by either potentially offending or embarrassing the patient. Perceptions of which team member is responsible for addressing sexual function varied.51 The physician, social worker, and psychologist most often are cited as responsible for sexuality intervention.

In yet another study on sexuality counseling following spinal cord injury, patients indicated a preference to speak with their occupational or physical therapist or nurse about their sexual concerns. Participants reported a positive response to therapists who used an open and direct style of communicating and otherwise were frustrated, embarrassed, or intimidated by therapists who did not. Although many of the subjects were not ready to discuss sexuality early in their rehabilitation, they concurred that knowing resources were available when they needed them was vital.49

Besides being neglected in the clinic, sexual rehabilitation has received little attention in research. However, a general positive correlation has been found between successful sexual rehabilitation and positive adjustment to disability. The literature shows that patients with disabilities are interested in the inclusion of sexuality in rehabilitation and give sexuality a high priority.27 Studies confirm that stroke survivors and their partners are interested in information and/or counseling about sexuality after stroke.20,41

In clinical rehabilitation, “a job title does not always define competencies,” and “no job title . . . excludes discussion of sexuality,” according to Chipouras and colleagues.12 The qualities necessary in a competent sexuality counselor for persons with disabilities have been described variously. Chipouras and colleagues12 emphasize comfort with sexuality, including one’s own, comfort with disability, empathy, nonprojection of one’s own morals onto the patient, awareness of available resources, basic knowledge of human sexuality, and awareness of one’s own competency and willingness to refer to others as necessary. The foundation of sexuality counseling consists of awareness and knowledge, which one can gain through reading, in-service education, coursework, and workshops. Therapists must develop skill in sexuality counseling through practice, as for all clinical skills. Discomfort in dealing with sexuality need be no different from discomfort with other difficult disability issues. Occupational therapists address many personal and sometimes painful issues with their patients. Increased competency, skill, and comfort comes with practice. Practice of sexuality interventions through role play with other staff members may be helpful in achieving greater comfort in conducting sexuality interventions.

Permission, limited information, specific suggestions, and intensive therapy

The therapist may use various frameworks and models to address sexuality issues in health care. Among the earliest and most prevalent is the PLISSIT model, developed by psychologist Annon.4 PLISSIT is an acronym for four levels of intervention: Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy (Fig. 25-1). Using this model, the practitioner can determine the type and extent of sexuality intervention needed, whether he or she has the skills to perform the intervention, and whether to refer to a more qualified counselor.

Figure 25-1 The PLISSIT model. PLISSIT, Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy.

Permission

Permission is the most basic and most frequently required intervention. Permission consists of reassuring patients that their actions and feelings are normal and acceptable. All occupational therapists should strive to perform permission-level sexuality interventions. Recognizing that sexual behavior varies widely and not projecting one’s own values or morals onto the patient is most important.

The practitioner must be proactive to provide patients with permission. Waiting for the patient to bring up sexual issues is not enough; the therapist must let the patient know that expressing sexual concerns is acceptable. The simplest way to do this is to ask, “People who have had strokes sometimes have concerns or questions about how they will be affected sexually. Do you have any concerns or questions in this area?” This line of questioning serves to normalize the concerns and gives patients the opportunity to say “no” if they are not comfortable discussing sexuality with that person at that time. Asking also lets patients know that sexual concerns are considered legitimate and gives them permission to bring up sexual issues again if their needs change. The therapist should ask questions in a language appropriate for the patient’s understanding, including the use of slang terms if necessary.

The best time to bring up sexuality is usually at the initial evaluation, when other ADL issues also are being addressed. If this is not feasible because of time constraints or because the evaluating therapist will not be treating the patient, sexuality should be brought up as soon as is comfortable. Sexual concerns should be explored before home visits and in the formulation of discharge plans because the patient’s needs and concerns change throughout rehabilitation.

Opportunities to give patients permission to express themselves as sexual beings often occur spontaneously. On one rehabilitation unit, a 38-year-old Hispanic man with a diagnosis of right cerebrovascular accident was playing a getting-to-know-you game with the other patients, all of whom were older women. As part of the activity, each member of the group was asked to name something he or she liked. The women named things such as chocolate, flowers, and pets. The man said, “I like women.” After a few seconds of silence, the occupational therapist running the group said, “Of course you do; what could be more natural?” The group members all nodded, and the activity continued.

Limited information

Sometimes simply reassuring patients about sexuality is not enough. If patients do have concerns or questions, they may require specific information related to their stated concerns. Most occupational therapists are qualified to provide patients with limited information. This level of intervention often is concerned with dispelling myths or misconceptions about sexuality. Limited information may be related to facts about the effect of disability on sexuality and sexual function. Handouts, pamphlets, and group education programs are good ways to provide limited information. The patients may read and absorb information on their own and ask the practitioner for clarification as needed. The important issue is to limit the information to the patient’s specific concerns. The accuracy of the information is also paramount. If the therapist does not have the information, he or she should help the patient get it before making a referral to another practitioner. For example, a patient with a recent stroke and complex cardiac history asks whether it is safe to have sex. Although the patient’s physician can provide the answer, it is not enough for the therapist to say, “Ask your physician.” By bringing up the concern to the therapist, the patient has chosen that person as an advocate. The therapist might respond, “Your physician is best equipped to answer that question. Would you feel comfortable asking him or her yourself, or would you like me to contact him or her for you?”

Specific suggestions

If a patient is experiencing a sexual problem, limited information may not be enough to solve it. The next level of intervention is specific suggestions aimed at solving the specific problem. This type of intervention requires more knowledge, time, and skill from the therapist but is appropriate for some occupational therapists (Box 25-1). The therapist should meet with the patient (and partner, if appropriate) in a comfortable, private setting and obtain a sexual problem history. This history should include the following:

The patient’s assessment of the problem and its cause, onset, and course

The patient’s assessment of the problem and its cause, onset, and course

Box 25-1 Competencies for Sexuality Interventions at Each PLISSIT Level

Permission

To perform this level of sexuality intervention, the therapist should do the following:

Acknowledge the sexuality of all persons.

Acknowledge the sexuality of all persons.

Be comfortable with his or her own sexuality.

Be comfortable with his or her own sexuality.

Believe that interest in sexuality is appropriate for everyone.

Believe that interest in sexuality is appropriate for everyone.

Be comfortable speaking directly about sexual issues (or be willing to overcome discomfort).

Be comfortable speaking directly about sexual issues (or be willing to overcome discomfort).

Refrain from projecting personal sexual morals and values onto others.

Refrain from projecting personal sexual morals and values onto others.

Limited information

To provide this level of intervention, the therapist should fulfill the criteria listed for Permission and do the following:

Have a basic understanding of human sexuality and its many variations.

Have a basic understanding of human sexuality and its many variations.

Understand the physiology of human sexual response.

Understand the physiology of human sexual response.

Be able to analyze the effects of physical disability on various sexual activities.

Be able to analyze the effects of physical disability on various sexual activities.

Be willing to seek and provide accurate sexual information.

Be willing to seek and provide accurate sexual information.

Be aware of the limitations of his or her own knowledge base.

Be aware of the limitations of his or her own knowledge base.

Just as the occupational therapist would not initiate treatment of other problems without a full evaluation, the therapist must understand the sexual problem fully before making specific suggestions. After obtaining the sexual problem history, the therapist should develop treatment goals in collaboration with the patient. These goals may address learning the effects of stroke on sexual function; adapting to changes in sensory, motor, or cognitive function; adapting to psychosocial and role changes; and improving sexual communication.

One male stroke patient reported sexual problems after a weekend visit home. A sexual problem history revealed that he had always preferred the male-superior position for intercourse. Since his cerebrovascular accident, increased leg extensor skeletal muscle activity and weakness had prevented adequate pelvic thrusting in this position. With his occupational therapist, the patient discussed various new positions to increase mobility: lying on the affected side with knees bent or sitting in a chair with his partner seated facing him.

Intensive therapy

If the patient’s problems are beyond the scope of goal-oriented specific suggestions, he or she may require intensive therapy. This level of intervention is based on specialized treatment skills and is beyond the scope of most occupational therapists. Finding an appropriate referral for such patients, such as a psychologist, social worker, or sex therapist, is advisable. If the sexual problems predate or are not related to the onset of disability, the patient may require referral.

The PLISSIT model enables the health care professional to adapt a sexuality program to the needs of the setting and the population served. Although permission to express sexual concern is universal, the need for limited information and specific suggestions varies. The best way to assess the need for sexuality intervention is to ask patients about their concerns. Occupational therapist Andamo’s treatment model3 uses a written problem checklist in which the patient is asked to identify problems in whatever role he or she fills, including that of sexual partner. By addressing sexuality in a multiproblem context, this model helps normalize sexual concerns. The checklist includes two items related to sexual problems and concerns about sexual activity. Patients who check either item receive further intervention as needed, including problem clarification, sexual history taking, and the development of treatment goals and planning. Therapists can adapt any evaluation to include verbal questions about sexual concerns and can repeat questions before home visits or as discharge approaches because patients’ concerns change over time.

Underlying some health care workers’ reluctance to address sexuality may be a fear of opening a Pandora’s box of issues too difficult or intimate for them to handle. This is seldom the case. Most persons do not wish to disclose their sexual problems or to include strangers in their intimate relationships. They want and benefit from the least intervention possible to help them solve their sexual problems and deal with their concerns. Other therapists fear that providing permission to discuss sexual concerns will facilitate inappropriate patient sexual behavior. Recent literature indicates that many health care workers are exposed to inappropriate sexual behavior on the part of patients during their careers, and they often lack training in dealing with these behaviors. Less experienced therapists and students tend to ignore the behaviors even when they are severe, which may result in high stress and difficult working conditions.35,50 Of course, any therapist who is exposed to sexual or other inappropriate behavior by anyone should address the problem immediately. Patient behaviors should be documented in the medical records; other staff members also may be affected. All new therapists and students should be encouraged to report harassment and seek help with difficult situations.

Providing permission to patients to address sexual issues directly actually decreases inappropriate behaviors. Flirting, sexual jokes, and innuendos are often a patient’s way of indirectly expressing doubts and concerns about sexuality after disability. One stroke patient, M.G., overheard his occupational therapist inviting some coworkers to her home and asked, “When are you going to invite me over?” The therapist replied, “You know, M.G., that I am your therapist, and although you’re a really nice person, it would be unethical for us to have a social relationship. But tell me, are you interested in developing new social relationships?” This question led to a lively discussion about M.G.’s returning interest in women and sex. The therapist was understanding and supportive. The patient made no further advances to her. By refocusing attention on the patient, the therapist deflected the unwanted attention and responded to the patient’s real need for permission to acknowledge his returning sexual feelings.

Developing competency

Competency in sexuality intervention comprises three elements (see Box 25-1): comfort, knowledge, and skill. These elements are interrelated; individuals are more comfortable with things they know well (knowledge) and do well (skill). Suggestions for improving these competencies follow.

Specific suggestions for treatment

Many impairments that occur after cerebrovascular accident may affect sexual function and sexuality. These deficits include sensorimotor, cognitive, communication, and psychosocial changes. With sexuality, as with other ADL, determining the underlying causes of the performance problem can be challenging. The following section comprises a list of suggestions one may use during treatment.

Hemiparesis/sensory loss

Patients with hemiparesis or sensory loss and their partners may try the following suggestions:

Having the hemiplegic partner lie on the affected side frees the uninvolved side for touching; this position also provides support, permits active movement, and focuses attention on the intact side. Early treatment by the rehabilitation team (occupational and physical therapy) should include instructing the patient to lie comfortably on the affected side (Fig. 25-2).

Having the hemiplegic partner lie on the affected side frees the uninvolved side for touching; this position also provides support, permits active movement, and focuses attention on the intact side. Early treatment by the rehabilitation team (occupational and physical therapy) should include instructing the patient to lie comfortably on the affected side (Fig. 25-2).

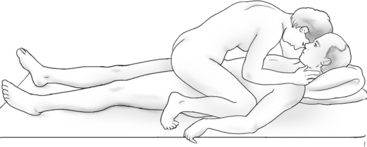

Impaired motor control (limb and trunk) may require a change in coital positioning because the hemiplegic partner may find it difficult to assume certain positions. Alternatively, the unaffected partner may assume the superior position in bed or on a chair or lying on his or her side (Figs. 25-3 to 25-5).

Impaired motor control (limb and trunk) may require a change in coital positioning because the hemiplegic partner may find it difficult to assume certain positions. Alternatively, the unaffected partner may assume the superior position in bed or on a chair or lying on his or her side (Figs. 25-3 to 25-5).

Positioning for comfort with the use of pillows can be incorporated into foreplay.

Positioning for comfort with the use of pillows can be incorporated into foreplay.

Partners should discuss sensory loss beforehand; in hemiplegia, there may be absent or diminished light touch, impaired proprioception, kinesthesia, or loss of stereognosis. Stimulation on areas of intact sensation and incorporation of stimuli to intact senses (e.g., using scents, keeping lights on for visual stimulation, music, and stimulating language) may help improve sensory abilities.

Partners should discuss sensory loss beforehand; in hemiplegia, there may be absent or diminished light touch, impaired proprioception, kinesthesia, or loss of stereognosis. Stimulation on areas of intact sensation and incorporation of stimuli to intact senses (e.g., using scents, keeping lights on for visual stimulation, music, and stimulating language) may help improve sensory abilities.

Individuals with severe sensory deficits must consider skin protection during sexual activity to prevent skin breakdown.

Individuals with severe sensory deficits must consider skin protection during sexual activity to prevent skin breakdown.

In the case of impaired hand function, a vibrator can be attached with the use of Velcro to enable stimulation.

In the case of impaired hand function, a vibrator can be attached with the use of Velcro to enable stimulation.

Treatment of weakened muscles of facial expression to improve body image and facial expression and strengthening of oral-motor muscles may enhance oral sexual activities such as kissing and oral-genital sex.

Treatment of weakened muscles of facial expression to improve body image and facial expression and strengthening of oral-motor muscles may enhance oral sexual activities such as kissing and oral-genital sex.

Figure 25-2 This position allows for genital fondling during rear entry vaginal or anal penetration and is appropriate for opposite or same-sex couples. Either partner can participate fully if lying on the hemiplegic side.

Cognitive/perceptual/neurobehavorial impairments

Patients with cognitive/perceptual/neurobehavioral impairments and their partners may try the following suggestions:

Simple positions are recommended (see Figs. 25-4 and 25-5). Achieving a routine of sexual activity may be helpful if the person has difficulty moving spontaneously. When the brain becomes used to a routine, it does not have to work as hard to plan movements and the patient does not have to concentrate on how he or she is moving.57

Simple positions are recommended (see Figs. 25-4 and 25-5). Achieving a routine of sexual activity may be helpful if the person has difficulty moving spontaneously. When the brain becomes used to a routine, it does not have to work as hard to plan movements and the patient does not have to concentrate on how he or she is moving.57

Hemianopsia or unilateral neglect may cause a person to ignore parts of the partner’s body or not respond when approached from the affected side. The unaffected partner must be sensitive to these deficits.

Hemianopsia or unilateral neglect may cause a person to ignore parts of the partner’s body or not respond when approached from the affected side. The unaffected partner must be sensitive to these deficits.

Nonverbal communication such as touching and gesturing are encouraged with partners who may have speech or language disorders.57

Nonverbal communication such as touching and gesturing are encouraged with partners who may have speech or language disorders.57

Distractions such as loud music should be kept to a minimum.57

Distractions such as loud music should be kept to a minimum.57

Individuals with memory impairment should keep a log of daily activities, including sexual activities, in an effort to remain oriented.57

Individuals with memory impairment should keep a log of daily activities, including sexual activities, in an effort to remain oriented.57

Sexual role changes such as increased sexual initiation by the nondisabled partner can help minimize the effects of cognitive changes on sexual function.

Sexual role changes such as increased sexual initiation by the nondisabled partner can help minimize the effects of cognitive changes on sexual function.

Partners may share fantasies or intimate thoughts in writing or by using augmentative communication devices before and after sexual activity.57

Partners may share fantasies or intimate thoughts in writing or by using augmentative communication devices before and after sexual activity.57

A team approach may be helpful. Speech and language pathologists can help the patient improve or compensate for verbal and nonverbal communication deficits.

A team approach may be helpful. Speech and language pathologists can help the patient improve or compensate for verbal and nonverbal communication deficits.

Decreased endurance

Patients with decreased endurance and their partners may try the following suggestions:

Sexual activities should be planned. The patient should wait three hours after meals before engaging in activities and avoid sex when fatigued. Instead, this may be a good time for intimate cuddling, hugging, or participating in massage.

Sexual activities should be planned. The patient should wait three hours after meals before engaging in activities and avoid sex when fatigued. Instead, this may be a good time for intimate cuddling, hugging, or participating in massage.

Partners can deemphasize intercourse through exploration of other sexual activities such as mutual masturbation and oral-genital sex.

Partners can deemphasize intercourse through exploration of other sexual activities such as mutual masturbation and oral-genital sex.

Partners should consider sexual positions that use less energy (see Figs. 25-4 and Fig. 25-5).

Partners should consider sexual positions that use less energy (see Figs. 25-4 and Fig. 25-5).

Sexual activities may be easier to do in the morning, when energy may be greater, instead of the evening.

Sexual activities may be easier to do in the morning, when energy may be greater, instead of the evening.

Inadequate vaginal lubrication

Patients with inadequate vaginal lubrication and their partners may try the following suggestions:

Erectile dysfunction

Patients with erectile dysfunction and their partners may try the following suggestions:

Medications for erectile dysfunction may be indicated, which include Sildenafil citrate (Viagra), Vardenafil (Levitra), and Tadalafil (Cialis).67 They are considered safe in combination with most cardiac medications and can be “safely recommended in all patients with stable cardiac conditions.”67 However, they all come with warnings about use in patients with history of stroke.64 Although inconclusive, sildenafil citrate has been reported to have potentially positive effects in the treatment of neurological disease, including stroke.22 For any person with stroke and/or cardiovascular disease, a physician should assess the safety of sexual activity and use of these medications.

Medications for erectile dysfunction may be indicated, which include Sildenafil citrate (Viagra), Vardenafil (Levitra), and Tadalafil (Cialis).67 They are considered safe in combination with most cardiac medications and can be “safely recommended in all patients with stable cardiac conditions.”67 However, they all come with warnings about use in patients with history of stroke.64 Although inconclusive, sildenafil citrate has been reported to have potentially positive effects in the treatment of neurological disease, including stroke.22 For any person with stroke and/or cardiovascular disease, a physician should assess the safety of sexual activity and use of these medications.

Certain medications may have an effect on erection in addition to the stroke itself. The patient and physician should discuss this possibility.

Certain medications may have an effect on erection in addition to the stroke itself. The patient and physician should discuss this possibility.

The patient and partner should consider alternatives to intercourse.

The patient and partner should consider alternatives to intercourse.

If erectile dysfunction is related to depression or another psychological issue, the therapist should suggest that the patient discuss it with the appropriate team member, such as the psychologist or psychiatrist.

If erectile dysfunction is related to depression or another psychological issue, the therapist should suggest that the patient discuss it with the appropriate team member, such as the psychologist or psychiatrist.

A ring placed on the base of the penis may help maintain blood flow into the penis and help the patient maintain an erection.

A ring placed on the base of the penis may help maintain blood flow into the penis and help the patient maintain an erection.

Other treatment options for erectile dysfunction require consultation with a urologist. These include vacuum constrictor devices, injection of vasoactive agents, and penile prosthesis implantation.32 Use of these therapies has not been studied in stroke survivors52 and has decreased greatly since the advent of sildenafil.18

Other treatment options for erectile dysfunction require consultation with a urologist. These include vacuum constrictor devices, injection of vasoactive agents, and penile prosthesis implantation.32 Use of these therapies has not been studied in stroke survivors52 and has decreased greatly since the advent of sildenafil.18

Incontinence

Patients with incontinence and their partners may try the following suggestions:

The patient should avoid fluids before engaging in sexual activity.40

The patient should avoid fluids before engaging in sexual activity.40

Men may wear a condom to prevent leakage onto the partner.

Men may wear a condom to prevent leakage onto the partner.

Patients on a voiding schedule should be encouraged to adhere to the schedule to prevent accidents.

Patients on a voiding schedule should be encouraged to adhere to the schedule to prevent accidents.

Towels should be available in case of accidents, and the patient should discuss his or her situation before engaging in sexual activity to prevent embarrassment.

Towels should be available in case of accidents, and the patient should discuss his or her situation before engaging in sexual activity to prevent embarrassment.

The patient should empty his or her bladder before engaging in sexual activity.

The patient should empty his or her bladder before engaging in sexual activity.

Pelvic muscle reeducation (with or without biofeedback) to improve strength and control of pelvic floor muscles may be indicated.58

Pelvic muscle reeducation (with or without biofeedback) to improve strength and control of pelvic floor muscles may be indicated.58

Contraception and safer sex

Most stroke patients are past the childbearing years; however, contraception remains an issue for those who are still fertile. Menses may be affected after a stroke, although studies are inconclusive.48 However, the exploration of contraceptive methods may be necessary, depending on the patient’s impairments. The functional abilities needed to use condoms, a diaphragm, or a cervical cap include fine motor abilities, motor praxis, and intact cognitive and perceptual function.57 However, in some cases, the nondisabled partner can assist with contraception and work it into the sexual repertoire. For example, if a woman had a stroke and her contraception of choice is the diaphragm but she cannot insert the device because of hemiplegia, her partner might do this for her. If the couple prefers, they can explore alternative methods of contraception. A review of other methods may be warranted, particularly if the patient previously used the pill or other contraceptive hormones, which have side effects, some of which affect circulation.72

Latex condoms are preferred for safer sexual practices against sexually transmitted diseases; however, an erect penis is required. If the male has difficulty maintaining or achieving an erection, it may not be possible for him to use condoms effectively. Female condoms or alternative sexual practices minimizing contact with body fluids may be explored, and individuals and couples should be educated on options such as mutual masturbation and oral sex with the use of a dental dam, which is a latex sheet placed over the vulva during cunnilingus. The therapist is responsible for staying updated on current guidelines related to safer sex practices if education on safer sex will be included in treatment.

CASE STUDY 1 “When Will My Husband’s Sex Drive Return?”

P.R. is a 52-year-old married man who previously suffered a hemorrhagic left basal ganglia stroke. He was admitted to a subacute rehabilitation center with right hemiplegia and language and short-term memory deficits. His right upper and lower extremity sensation was absent for tactile stimulation. He demonstrated increased flexor activity and had no active arm movement. P.R. required maximal assistance with all transfers and ADL, and his activity tolerance was poor. Before admission he had lived with his wife of 1½ years and ran a business requiring frequent travel. P.R.’s wife also worked full-time and taught women’s exercise classes in her free time.

By his 18-day team conference, P.R. had made substantial gains. He was independent in stand-pivot transfers and required minimal assistance in dressing. He demonstrated emerging sensation and motor control in his right arm and lower extremities. He was able to walk during physical therapy with a cane and assistance from a therapist. His language function had improved, with only some word-finding deficits remaining. He and his wife attended the team meeting. Her last question to the team was, “When will his sex drive return?” P.R. said, “Don’t worry, Honey, it will come back like everything else.” The staff recommended discussing this issue with the new neurologist, with whom the couple had an appointment the following day.

On return from his neurologist, P.R. reported to his speech therapist that he and his wife had “forgotten” to bring up sexuality. He reported achieving only partial erections. The therapist offered him a consultation with an occupational therapist on staff who was knowledgeable about sexuality and disability, and he agreed. The speech therapist had received no training or information about sexuality and had no experience in this area. P.R.’s treating occupational therapist, who was not present at the team meeting, was willing to use part of P.R.’s scheduled treatment time for the sexuality intervention.

The occupational therapist who specialized in sexuality issues introduced herself to P.R. and made an appointment to meet with him the next week in his private room. She asked whether he had any specific questions or concerns so she could prepare information for their meeting. He said the concerns were mostly his wife’s and that he was confident his sex drive would “return just like use of my arm and leg are going to return.” The occupational therapist suggested including P.R.’s wife in the meeting, but P.R. said she was unavailable during the daytime so the occupational therapist might as well speak to him alone.

A brief sexual history revealed that P.R. had been single for 11 years before this second marriage and that he had been sexually active with a variety of women during that time. He and his wife considered sex an extremely important part of their relationship. “People can be very sexy even though they don’t look it,” he explained. P.R. volunteered that he and his wife would not need help with sexual positioning for intercourse because they preferred the female-superior position. P.R. admitted to decreased sexual desire, which he attributed to fatigue, separation, and the nonconducive environment. He reported having erections that he estimated at “three quarters of normal hardness,” which was an improvement. He reiterated that he was sure everything would come back.

The intervention included three levels of the PLISSIT model.

Permission

The therapist assured P.R. that concern about sexuality was common among stroke survivors and their sex partners and that, after a life-threatening event, sexual concerns are a sign of returning health. They discussed the myth that middle-aged persons are not attractive and society’s insistence in portraying only young, thin, beautiful persons as “sexy.” The therapist explained that although health care workers are sometimes reluctant to bring up sexuality, P.R. had the right to be assertive in getting any assistance he needed in this area.

Limited information

P.R. was provided a verbal summary of the research on stroke and sex. He was informed that some persons experience sexual dysfunction after stroke and that desire, libido, erection, ejaculation, and orgasm might be affected. The therapist emphasized the lack of correlation of sexual dysfunction to motor or sensory deficits and the high correlation between prestroke and poststroke sexual function. The therapist and P.R. discussed the effect of antihypertensive medications on sexual function. P.R. reported telling his physician that he would not take any medication that had side effects on sexual function. The physician prescribed a medication without sexual side effects.

Specific suggestions

Although P.R. reported no need for ideas to improve his sexual function, a level of denial was evident in his assurances that “everything would come back.” The occupational therapist said, “Just as you’re participating in therapy to improve your arm, leg, and speech, your sexual function will improve faster if you don’t just sit around waiting for its return.” P.R. agreed that he felt as if he had a new, different body and that he would find it helpful to explore and learn the responses of the new body. They discussed including his wife in the sexual explorations, but she was uncomfortable with the lack of privacy in the facility.

Because P.R. would be unlikely to have sexual relations with his wife before discharge, strategies were discussed for initiating sexual activity in a positive, nonthreatening way because early problems with erectile function are not necessarily predictive of continuing problems. Alternative sexual activities also are considered “real sex.”

Because of their prestroke sexual function, motivation, interest, maturity, and willingness to communicate, P.R. and his wife were likely to make a good sexual adjustment to the effects of stroke. However, the therapist did offer information on treatment of erectile or other sexual dysfunction, for in the future, if problems arose, she would not be available to P.R. after discharge. She also reported the latest medical interventions for erectile dysfunction, which would be familiar to any urologist. Although he felt he would not need it, P.R. seemed glad to know that treatment was readily available.

At this facility, sexual concerns were not addressed by any rehabilitation discipline. While treating P.R., the therapist had provided written information on the sexual effects of cerebrovascular accident and the role of speech and language therapists in sexuality counseling to the speech therapist who referred him and summarized the results of the counseling session. Staff members became aware that other patients might have sexual concerns but lacked the comfort level or assertiveness to initiate the communication. The therapist was asked to provide an in-service on sexuality, which was well-attended by members of the occupational therapy department and other interested staff.

CASE STUDY 2 “I Want to Get Out of the Wheelchair So I Can Chase a Man”

W.A. is a 62-year-old woman who previously suffered a right middle cerebral artery stroke with resulting left hemiparesis. After her initial and rehabilitation hospitalizations, she was discharged home for continued occupational and physical therapy. She lived in a senior housing development, which had a social room on the premises. W.A. had been widowed for more than 15 years and reported that her husband had been an alcoholic and a “terrible man.” During W.A.’s initial evaluation at home, the occupational therapist asked what her goals for rehabilitation were. W.A. was quick to reply, “I want to be able to get out of the wheelchair so I can chase a man.” Sexuality had not been addressed until this point in the evaluation. The therapist took the opportunity to ask W.A. whether she had a significant man in her life, to which W.A. replied “no.” The therapist asked W.A. whether she had any concerns about resuming sexual activities after the stroke; again W.A. replied “no.” She explained that she was not looking to marry again and simply wanted to be exposed to others so she could flirt. During this conservation, the therapist realized that further exploration of sexual function was geared toward getting W.A. out into the community again. W.A. had been limited in this endeavor because of poor mobility and wheelchair dependency.

In this example, the therapist used the permission level of the PLISSIT model. The patient brought up the topic herself, and it was discovered through further questioning that W.A. was really referring to a need to socialize, not so much as to act on her sexual desires. In subsequent conversations, W.A.’s occupational therapist reassessed this situation, particularly as W.A. made progress with ADL and functional mobility. After six months of treatment, W.A. was getting back out into the community, attending an adult day care center, and participating in bingo games in her building. She was taught how to transfer on and off the furniture in the social room to allow greater independence and a sense of normalcy. All areas of function, including sexuality, were reevaluated periodically during W.A.’s treatment program, and her goals remained unchanged from her initial evaluation.

In this example, the issue of sexuality was related less directly to actual sexual activities than to socialization and flirting. Had the therapist neglected to pursue W.A.’s early statement about wanting to “chase a man,” the patient’s needs might never have been met.

CASE STUDY 3 “Will I Ever Have Sex Again?”

L.E. was a 57-year-old woman with an unknown social history who was admitted to a rehabilitation hospital and who previously suffered a right cerebrovascular accident with left hemiplegia and perceptual deficits. At the initial evaluation, the occupational therapist asked whether L.E. had any sexual concerns. “Yes, I want to know whether I’ll ever have sex again,” she said tearfully. The occupational therapist realized that such a question could not be answered and that the patient’s concerns needed clarification. Was L.E. concerned about being able to find a partner? About “performing” sexually? The therapist helped L.E. clarify her question with some probing, “What are you concerned about specifically? What do you think might get in the way of your having sex again?” L.E. reported having a male friend with whom she had an active sex life. Her major concerns were whether she would regain enough function to return home and whether sexual activity would provoke further strokes. The occupational therapist reassured L.E. that most persons can resume sexual activity safely after a stroke and offered to help her consult her physician for medical clearance. The therapist provided the limited information L.E. was looking for through reassurance and by obtaining medical clearance through another team member (that is, the physician). The therapist was able to tie in all the rehabilitation goals with the patient’s desire to return to her home and previous lifestyle, which strengthened the collaboration between L.E. and the rehabilitation staff.

Program development

The therapist should have support, resources, and referrals available when addressing sexual issues. The therapist should inform supervisors and others on the rehabilitation staff of activities. Resources and referral services should be identified in other departments and outside the facility, if appropriate. The therapist should check the existing policies on sexuality (if any) at the facility and strive to be in compliance. The therapist should report experiences and provide education to others. If possible, an interdisciplinary committee should be formed to address sexual issues and develop appropriate programs.

Documentation and billing

Sexuality interventions may be billed and documented in various ways, depending on the billing system and the issues discussed. Appropriate categories include ADL training, patient and family education, discharge planning, and psychosocial training.

As in treatment, sexuality is best addressed in a multiproblem context. Patient privacy and confidentiality must be maintained. Examples of goals include the following:

Summary

All persons are sexual, and sexual activity is important to most persons throughout their lives. Interest in or desire for sexual activity does not necessarily diminish as persons grow older. Stroke may interfere with sexual expression by affecting the survivor’s desire, libido, erectile or lubrication response, orgasm or ejaculation, and sensorimotor, cognitive, psychosocial, ADL, and role function. Stroke also may affect the partner’s response or the patient’s ability to find a sexual partner. Research has shown that sexual desire most often is affected; however, prestroke sexual activity is the strongest predictor of poststroke sexual activity. Occupational therapists can use a holistic approach and training in activity analysis and adaptation to assist persons who have had strokes to regain their desired sexual function. A team model is best for sexual rehabilitation, with each team member knowledgeable about sexuality and providing special expertise. The PLISSIT model helps the practitioner identify the type of sexuality intervention required. All occupational therapists should be able to provide patients with permission, limited information, and specific suggestions and should be able to make appropriate referrals for sexual concerns related to stroke. Therapists must be sensitive to the multiple components of sex.

Review questions

1. What are the stages of the sexual response cycle and the associated physiological changes in males and females?

2. What are some of the normal changes in sexual function in aging men and women?

3. Why does sexual activity decline among older persons?

4. What are the four levels of sexuality intervention in the PLISSIT model? Which may be performed by occupational therapists?

5. What skills are needed to provide sexuality counseling to patients who have had strokes?

6. What common effects of stroke interfere with sexual function and sexuality? What are the best predictors of poststroke sexual function?

1. Aloni R, Ring H, Rosenthal N, et al. Sexual function in male patients after stroke a follow up study. Sex Disabil. 1993;11(2):121.

2. Aloni R, Schwartz J, Ring J. Sexual function in post-stroke female patients. Sex Disabil. 1994;12(3):3.

3. Andamo EM. Treatment model. occupational therapy for sexual dysfunction. Sex Disabil. 1980:3;1:26.

4. Annon JS. The PLISSIT model. a proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. J Sex Educ Ther. 1976:2;1:1-15.

5. Bener A, Al-Hamaq A O A A, Kamran S, Al-Ansari A. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction in male stroke patients, and associated co-morbidities and risk factors. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40(3):701-708.

6. Boldrini P, Basaglia N, Calanca MC. Sexual changes in hemiparetic patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72(3):202-207.

7. Bray GP, DeFrank RS, Wolfe TL. Sexual functioning in stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1981;62(6):286-288.

8. Burchardt M, Burchardt T, Baer L, et al. Hypertension is associated with severe erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2000;164(4):1188-1191.

9. Burgener S, Logan G. Sexuality concerns of the post-stroke patient. Rehabil Nurs. 1989;14(4):178-181.

10. Chen K, Chiou CF, Plauschinat CA, et al. Patient satisfaction with antihypertensive therapy. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19(10):793-799.

11. Cheung RTF. Sexual functioning in Chinese stroke patients with mild or no disability. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;14(2):122-128.

12. Chipouras S, Cornelius DA, Makas E, et al. Who cares? A handbook on sex education and counseling services for disabled people, ed 2. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press; 1982.

13. Cole TM, Cole SS. Rehabilitation of problems of sexuality in physical disability. In Kottke FJ, Lehman JF, editors: Krusen’s handbook of physical medicine and rehabilitation, ed 4, Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990.

14. Coslett HB, Heilman KM. Male sexual function. impairment after right hemisphere stroke. Arch Neurol. 1986:43;10:1036-1039.

15. Couldrick L. Sexual expression and occupational therapy. British Journal of occupational Therapy. 2005;68(7):315-318.

16. Cushman LA. Sexual counseling in a rehabilitation program. a patient perspective. J Rehabil. 1988:54;2:65-69.

17. DeBusk R, Drory Y, Goldstein I, et al. Management of sexual dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease. recommendations of the Princeton Consensus Panel. Am J Cardiol. 2000:86;2:175-181.

18. Ducharme S. From the editor. Sex Disabil. 2002;20(2):105-107.

19. Duncan LE, Lewis C, Jenkins P, et al. Does hypertension and its pharmacotherapy affect the quality of sexual function in women. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13(6 pt 1):640-647.

20. Edmans J. An investigation of stroke patients resuming sexual activity. Br J Occup Ther. 2002;61(1):8-36.

21. Evans J. Sexual consequences of disability. activity analysis and performance adaptation. Occup Ther Health Care. 1987:4;1:1.

22. Farooq MU, Naravetla B, Moore PW, et al. Role of sildenafil in neurological disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2008;31(6):353-362.

23. Francis ME, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Eggers PW. The contribution of common medical conditions and drug exposures to erectile dysfunction in adult males. J Urol. 2007;178(2):591-596.

24. Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L. Post-stroke hemiplegia and sexual intercourse. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1980;7:158-166.

25. Garden FH. Incidence of sexual dysfunction in neurologic disability. Sex Disabil. 1991;9(1):1.

26. Garden FH, Smith BS. Sexual function after cerebrovascular accident. Curr Concepts Rehabil Med. 1990;5:2.

27. Gatens C. Sexuality and disability. In Woods NF, editor: Human sexuality in health and illness, ed 3, St Louis: Mosby, 1984.

28. Giaquinto S, Buzelli S, DiFrancesco L, et al. Evaluation of sexual changes after stroke. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(3):302-307.

29. Goddess ED, Wagner NN, Silverman DR. Poststroke sexual activity of CVA patients. Med Aspects Hum Sex. 1979;13:16.