2 Professional reasoning in context

The previous chapter explored different types of knowledge that professionals need to combine in order to make reasoned action. These include: (a) generalized, propositional knowledge that is often generated through research (episteme); (b) practical wisdom or professional craft knowledge, which is context-specific knowledge and relates to professional ‘know-how’ (phronesis); and (c) personal knowledge, which refers to a professional’s knowledge of him- or herself as a person. Sackett’s (2000) definition of evidence-based medicine was used to highlight the need to combine these different types of knowledge, which can be sourced from research, professional expertise and an awareness of patient/client values specifically and human concerns more generally, when making professional decisions.

We propose that, when combining all of these different types of knowledge to make decisions in specific contexts about particular clients (and considering their particular situations), models of practice can provide useful frameworks for organizing this varied information. As discussed in Chapter 1, occupational therapy theory is embedded within models of practice. Therefore, using them to combine information should help occupational therapists to seek and interpret information relevant to the profession’s domain of concern.

The process of making professional decisions is influenced by context. The particular information that is sought by occupational therapists as a basis for professional decision-making is not only shaped by the profession’s domain of concern but also by the organizational and sociopolitical and cultural contexts within which the occupational therapist works. In this chapter, we refer to the literature on professional reasoning to better understand how occupational therapists navigate the process of making professional decisions in context. We present professional practice as a complex endeavour that requires judgement and critical reasoning, has ethical and practical dimensions, requires the logical use of ‘facts’ and generalized theoretical principles and occurs within the context of various communities of practice (both professional and organizational).

First, we explore the nature of professional practice in terms of its roles and expectations within Western society and the implications of these for professional reasoning and judgement. Second, we look at the practice of occupational therapy and present a historical account outlining how professional reasoning of occupational therapists has been investigated. Third, we propose a model of professional reasoning in context. Finally, we discuss the role of occupational therapy practice models in supporting professional reasoning.

The nature of professional practice

Occupational therapy is an important profession to society. Therefore, we commence our investigation of occupational therapy practice by considering the nature of professional practice more generally, beginning with the question: what does it mean to be a professional? According to Coles (2002), “society asks certain of its members to be professionals – to undertake certain tasks and perform certain roles that others cannot or will not do” (p. 3). This definition associates professionalism with social roles. Blair (1998) defined social role as guiding “the behaviour expected of an individual because of the social status occupied. For example, the behaviour expected of a health professional is specific expertise and proven ability to alter the illness or problem experienced by an individual” (p. 45). The social status that Blair mentions refers to both rights and obligations that are afforded on the basis of professional status.

Professionals like occupational therapists have a particular place in the social hierarchy, in that they are expected to perform tasks that others are not expected to perform and they have certain rights and obligations that others don’t have. These rights include higher levels of financial remuneration and greater autonomy, for which society expects a higher level of expertise (obligations). This expertise relates to both skills and knowledge, in that particular professions often claim particular skills as exclusive to that profession and each profession has to demonstrate a particular and extensive knowledge base that others in society would not normally be expected to possess.

Professions also are afforded a level of autonomy, in that professions are not expected to detail everything they do and the reasoning behind those actions. This is partly because their reasoning is expected to be based on their extensive and particular knowledge base. It follows, then, that only others who have that same knowledge base can fully understand what is required of and appropriate to that particular profession. Therefore, professions are expected to engage in self-regulation (Coles, 2002).

Fish and Coles (1998) summed up well the status of professions in our society in the following statement:

Professionals are expected to be trustworthy, and in their turn they expect to receive the public’s trust in them. In return professionals were prepared to undertake a lengthy period of education, which for many was particularly protracted in order for them to gain higher professional qualifications. They were prepared to commit considerable amounts of time and effort to their work. They did not watch the clock, or do it for the money. They did more than was asked of them. They went further than their contracts of employment. All because they felt it was right to do so. They were professionals. They stood somewhat apart from the rest of society. They took on a professional role. And in recompense for their personal commitment, society gave them professional status, a greater than average income. For this society expected high ethical standards of course, and the maintenance of confidentiality. The tacit agreement was this: society would trust professionals if they could be trusted. (p. 4)

One way that professions demonstrate their trustworthiness is through the development of codes of ethics. These are statements of the types of behaviours that can be expected of members of that particular profession. Often professionals have access to privileged and sensitive information and they need to be able to assure society that they will deal with this information properly. In the context of the helping professions, this sensitive information usually relates to those receiving services, that is, clients. For example, clients often have to disclose very personal information about themselves to professionals and might have to participate in activities (such as having a person they don’t know very well toilet or shower them) which require a higher level of physical contact than they would have with many people they know very well. Therefore, the codes of ethics of the helping professions detail the nature of the relationships in which professionals will and will not engage, how the rights of those people receiving services will be upheld and protected, and how information relating to those people will be handled. Consequently, codes of ethics usually contain statements about respecting clients and their privacy, maintaining relationships that have appropriate boundaries and that acknowledge the power imbalance inherent in professional relationships, and providing competent and effective services.

The purpose of codes of ethics is associated with the autonomy afforded and self-regulation expected of professions. While codes of ethics are necessary for outlining the behaviours that society should be able to expect from professionals, they only provide the foundation for self-regulation. The reputation of a profession is dependent on the degree to which the behaviours outlined in these codes are adhered to by individual professionals and the support for professional standards that is provided by regulatory bodies.

Another distinguishing feature of professional practice is the expectation that professionals are able use judgement to determine the best course of action in any given situation. As professionals are asked to deal with complex situations and problems, professionals are expected to use their judgement to discern when to apply which procedures (and when to refrain from applying those procedures). Often, the ability to use a high level of judgement is the criterion used to distinguish between professionals and technicians, where technicians might have a high level of technical expertise but not the knowledge base required to make such judgements. For professional practice, it is not enough to have only the technical skills required to carry out a particular range of procedures, although these skills are necessary. Professionals are expected to use their extensive knowledge and apply this knowledge in different settings to address problems that present in a particular situation.

The primary purpose of this expert judgement is to make decisions about a course of action. Society expects professionals to be able to make decisions about action. Carr (1995) emphasized that professional action is not ‘right’ in an absolute sense (of there being a right thing to do) but that it is right when it is “reasoned action that can be defended discursively in argument and justified as morally appropriate to the particular circumstances in which it was taken” (p. 71, italics in original). Higgs et al. (2001) referred to professional practice as requiring “thoughtful action” (p. 5) in which professionals need to be able to take action to relieve or improve problems that clients encounter. Thus, the purpose of using professional judgement is to determine action that is reasoned and thoughtful.

Professionals are expected to use their profession’s knowledge base as a foundation for their judgements. Having a unique knowledge base is central to the notion of profession. As Higgs et al. (2001) described:

A ‘profession’ is an occupational group that is able to claim a body of knowledge distinctive to itself, whose members are able to practice competently, autonomously and with accountability, and whose members contribute to the development of the profession’s knowledge base. In the emergence of the health occupations as professions, propositional knowledge, derived from research and scholarship, was sought to provide the foundation of the professions’ knowledge base and their theory for practice, and to establish the professions’ status and credibility. (p. 4)

Traditionally, the ability to make professional judgements about appropriate action has been conceptualized as a process of applying theory, given that professionals are expected to possess extensive theoretical knowledge. However, this assumption has been questioned. Mattingly and Fleming (1994) stated of occupational therapists:

While [they] sometimes speak of clinical reasoning as the application of theory to practice, this is a deceptive statement. A grounding in theory is essential for expert practice but does not guarantee such practice. One cannot do without such grounding, but it, alone, will not yield good clinical interventions, because theoretical reasoning differs from practical reasoning. (p. 9)

If, as Mattingly and Fleming (1994) argued, theory is essential for professional practice but insufficient to guarantee expert practice, then professionals might need a range of different types of knowledge and skills to support their practice. As professionals need to both make judgements and engage in reasoned action, they need information that supports them to gain an expert understanding of the overall situation as well as information that provides the basis for judgements about action.

In Chapter 1, we discussed three different types of knowledge that professionals use, which could be categorized as either propositional or non-propositional knowledge. All three types of knowledge are necessary for expert and well-reasoned professional practice. By understanding the general principles conveyed through propositional knowledge, professionals can generate an understanding of the specific situation from a broader perspective of how things are structured and operate (e.g. using knowledge bases such as anatomy, physiology, psychology, sociology), knowledge of the general effectiveness of particular interventions (using ‘evidence’ generated from systematic research such as randomized controlled trials) and the perspective generated by theories that underpin the particular profession to which the professional belongs. However, they also need non-propositional knowledge. Context-specific professional craft knowledge underpins their ability to judge what action is required in the specific situation and to know how to carry out that action. Personal knowledge is used for the interpersonal aspects of professional action, as the ability to listen to, communicate with and develop a professional relationship with clients is well recognized as an essential component of professional practice (Price, 2009).

In summary, to be a professional means to fulfil a social role. This comes with social expectations as well as social privileges. The expectations include ethically sound behaviour and the ability to make well-reasoned and thoughtful judgements about action. These expert judgements are expected to be based on a unique and extensive base of propositional knowledge. Increasingly, it is recognized that well-reasoned judgements also rely on non-propositional knowledge such as professional craft knowledge and personal knowledge.

Communities of practice

While professional practice is situated within the context of a society that expects its professionals to be able to provide services that are not expected of others, it also exists within the historical and social context of a particular profession. Carr (1995) made the point that to practise as a professional:

is always to act within a tradition, and it is only by submitting to its authority that practitioners can begin to acquire the practical knowledge and standards of excellence by means of which their own practical competence can be judged. (pp. 68–69)

Professionals are expected to develop expertise in a particular type of practice, but how does this occur? A traditional approach to this question is to focus on the knowledge and skills that characterize the practice of a particular profession. From this perspective, teaching student and novice professionals the knowledge and skills of the profession is the logical approach to the development of expertise. The structure of many professional courses requires students to demonstrate their acquisition of the knowledge base that underpins practice as well as those skills deemed necessary for that particular kind of practice. In addition, practice educators recognize the importance of practical experience in developing expertise (Evenson, 2009). Consequently, bodies such as the World Federation of Occupational Therapists outline what they conceive as minimum standards for professional education that include a minimum number of hours of practice-based learning (Hocking & Ness, 2002). Professional expertise is based on practical experience as well as the acquisition of knowledge and skills.

Sociocultural approaches to learning provide a useful way of explaining the development of professional expertise. These approaches “explain learning and the development of expertise in terms of an individual’s enculturation into the cultural practices or activities of their society and, more particularly, into the subcultures or communities of that society” (Walker, 2001, p. 24). Lave and Wenger (1991) used the term ‘communities of practice’ (p. 29) to refer to the communities to which individuals belong and within which they engage in situated or context-specific learning. Individual professionals develop expertise by participating in the cultural practices of the community of practice (in this case the profession, but they could also refer to multidisciplinary teams that the occupational therapist works in). Cultural practices include actions that are routine within a particular group. Often the practices are so accepted and routine that they might not be noticed by the group itself. As such, these practices are often described as tacit or embedded in practice, because they are probably not usually put into words or commented on.

From this perspective, professional learning is not simply the acquisition of skills but involves a transformation in the way that an individual participates in their community of practice. This process of transformation is a mutual one. As Walker (2001) explained, “As individuals are enculturated into the practices of their society and communities, they are transformed by the experience, and simultaneously may transform the community’s practices” (p. 24). Participating in cultural practices contributes to a transformation in the professional’s identity and action. The transformation of practices that results from such participation also contributes to the growth and development of the profession. In many ways, the models reviewed in this book could be seen as cultural artefacts (Iwama, 2007, p. 185) and reviewing how they have changed over time demonstrates one type of transformation that has occurred in the profession of occupational therapy. As Walker noted, cultural practices are interconnected but “have their own histories and trajectories and are part of, and linked to, other practices” (p. 24).

Professional relationships appear to be important for learning cultural practices. Parboosingh (2002) proposed that the interactions and relationships that professionals have with each other are important to the learning that occurs through participation in communities of practice. He stated, “the experiences of practitioners suggest that interacting with peers and mentors in the workplace provides the best environment for learning that enhances professional practice and professional judgment” (p. 230). In occupational therapy, Unsworth (2001) also proposed that “novice therapists could benefit from spending more time reflecting on the therapy process, and discussing their therapy with expert colleagues” (p. 163). Coles (2002, p. 7) explained that such learning also changes practice by leading to the “critical reconstruction of practice”, that is, developing and enriching practice traditions, rather than just reproducing current practice.

In summary, practice expertise or practical wisdom is built through participation in communities of practice and enhances professional practice and professional judgement. Professional expertise requires extensive and relevant propositional knowledge bases and the ability to exercise professional judgements in order to make decisions about the best course of action in a particular situation. Practical wisdom is highly context-specific. Professionals have to combine and evaluate different types of knowledge in order to make practice decisions. A variety of terms are used to refer to the processes they use to do this. These terms include professional reasoning, clinical reasoning, professional or clinical judgement, and professional or clinical decision-making. Now we turn to an exploration of professional reasoning in occupational therapy.

Occupational therapy professional reasoning

Coles (2002) defined professional practice as “the exercise of discretion, on behalf of another, in a situation of uncertainty” (p. 4). This definition points to the requirement for professionals to make judgements that will affect their clients and that such judgements are often made in conditions of uncertainty. The uncertainty of the situations in which professional practice takes place (Coles, 2002; Hunink et al., 2001) and the need for professional judgements are well recognized (Higgs & Jones, 2008).

As professionals, occupational therapists need to be able to make well-reasoned decisions about their professional action. In this section of the chapter, we discuss professional reasoning from a historical perspective, explore the nature of occupational therapy practice as requiring art, science and action, and propose a model for conceptualizing context-specific reasoning in occupational therapy.

Historical view of professional reasoning in occupational therapy

In occupational therapy, research into the process of thinking and making judgements in practice has generally adopted the term clinical reasoning. This term was used in medicine and the early conceptualizations of occupational therapy reasoning were largely influenced by that research. The initial clinical reasoning research in occupational therapy was conducted by Joan Rogers and her colleagues in the early 1980s (Rogers, 1983; Rogers & Masagatani, 1982). At that time, clinical reasoning was generally understood from the perspective of artificial intelligence, with its focus on acquiring and managing information. Therefore, clinical reasoning was described as a process involving the acquisition and interpretation of cues (information) and the generation and testing of hypotheses (about what the cues might mean and their implications for professional action). This way of thinking often was called logico-deductive reasoning, because the emphasis was on a logical process of systematically collecting, combining and interpreting information in the light of established theories (i.e. deducing meaning).

Research funded by the AOTA and conducted by Cheryl Mattingly and Maureen Hayes Fleming in the late 1980s has dominated subsequent thinking about clinical reasoning in occupational therapy. Mattingly and Fleming (1994) presented their observations of clinical practice in a large rehabilitation facility in the United States of America. They argued that reasoning could be categorized into four different types: procedural, interactive, conditional and narrative. This work was influential, not only through the results of their methodologically rigorous research, but through introduction of the idea that occupational therapists might have multiple ways of reasoning. Prior to their work, clinical reasoning in occupational therapy had been conceptualized (in the same way as medicine) only as a hypothetico-deductive process. In contrast, Mattingly and Fleming stated that, in occupational therapy, “different modes of thinking are employed for different purposes and in response to particular features of the clinical problem complex” (p. 17).

Using the term the three track mind, Mattingly and Fleming (1994; also see Fleming, 1991) observed that occupational therapists switched between the first three of the four types so rapidly that they appeared to be using them simultaneously. First they used procedural reasoning, which relates to situations in which therapists focused on defining problems and considering intervention possibilities. They thought about the procedures they might use to remediate the person’s problems with functional performance. Second, an interactive mode of reasoning was used when the therapist wanted to “interact with and better understand the person” (p. 17). This understanding appeared to be particularly important when the therapist wanted to tailor their intervention for the particular client. The third type of reasoning that formed part of the three track mind was conditional reasoning, which is “a complex form of social reasoning, [that] is used to help the patient in the difficult process of reconstructing a life that is now permanently changed by injury or disease” (p. 17). It is interesting to read their comments about this type of reasoning because it alludes to the problems of trying to put language to practice when much of it is embedded within practice and not generally put into words. They wrote, “The concept of conditional reasoning is perhaps the most elusive notion in our proposed theory of multiple modes of thinking. Yet we are firmly, if intuitively, convinced that there is a third form of reasoning that many experienced therapists used. This reasoning style moves beyond specific concerns about the person and the physical problems and places them in broader social and temporal contexts.” (p. 18.) In addition to the three modes of reasoning that contributed to the three track mind, the final form of reasoning these authors proposed was a narrative mode of reasoning in which occupational therapists swapped stories and engaged others in discussing puzzling situations. They suggested that this storytelling also served as a way to enlarge each other’s “fund of practical knowledge” vicariously (p. 18).

In 1993, Schell and Cervero published an “integrative review” of the clinical reasoning literature at the time. As a number of terms had been used to discuss different aspects of clinical reasoning that could be categorized as predominantly hypothetico-deductive, such as diagnostic reasoning (Rogers, 1983) and procedural reasoning (Mattingly, 1991; Mattingly & Fleming, 1994), Schell and Cervero grouped these together and labelled the category “scientific reasoning”. This term was adopted by other authors and used frequently in subsequent publications relating to clinical reasoning in occupational therapy. Possibly taking Mattingly’s and Fleming’s lead of proposing that occupational therapists use multiple modes of reasoning, Schell and Cervero proposed an additional category of reasoning, which they called “pragmatic reasoning”. Pragmatic reasoning referred to those times when occupational therapists thought about what actually could be done, given the practice resources available in the situation, the broader organizational and political context and the wishes of the client. They also made reference to ethical reasoning, where occupational therapists attended to what should be done (Rogers, 1983).

These earlier studies were followed by a continued interest in clinical reasoning over the following years, with a number of journals publishing special editions on clinical reasoning in the mid 1990s. More recently, Unsworth (2005) undertook research to test the presence of the various types of reasoning that had been described. She concluded that occupational therapists do appear to use procedural, interactive, conditional and pragmatic reasoning (proposing that this last one was more related to the influence of the practice environment than to the therapist’s personal philosophy − both of which had been proposed by Schell & Cervero earlier) and that occupational therapists also seemed to use a process of linking the current situation to broader principles. She called this process “generalization reasoning” and proposed that it was a subcategory of each of the other types of reasoning. Examples of generalization reasoning included making generalizations about people with a particular medical diagnosis and general principles relating to the provision of services (both in that organization or service context and relating more specifically to occupational therapy interventions).

Art, science and action

When discussing the complexity of practice, Mattingly and Fleming (1994) observed that occupational therapy was a profession between two cultures, the culture of biomedicine and its own professional culture. As they stated, “one of the most interesting features of occupational therapy practice is that it tends to deal with functional problems that fall nicely within biomedicine (treating physical injuries with specific treatment techniques), as well as problems going far beyond the physical body, encompassing social, cultural, and psychological issues that concern the meaning of illness or injury to a person’s life” (p. 37). In labelling this observation, they referred to occupational therapy as a “two-body practice” (p. 37) where occupational therapists attend to both physical and phenomenological bodies.

As discussed in the Introduction, a biomedical perspective most highly values the scientific method as a way of generating knowledge. It is characterized by a focus on the physical body and dominated by the body-as-machine metaphor. Mattingly and Fleming (1994) contrasted this with a phenomenological perspective, which focuses on the experience of illness rather than the physical impairment. This experiential dimension is often referred to as the lived body (referring to the body as it is lived or experienced) and is consistent with the concept of subjective experience, which is part of a biopsychosocial approach.

While different professions attend to both perspectives to various degrees, Mattingly and Fleming (1994) commented that occupational therapists are seemingly unique among the health professions by attending to both features equally. Similarly, Blair and Robertson (2005) claimed that occupational therapy lies on “what might be considered to be a ‘professional fault line’ between health and social care” (p. 272), whereby they seemed to be equating healthcare with a scientific, biomedical approach and social care with a perspective more concerned with people’s social and personal welfare. This dual orientation might contribute to the complexity of reasoning required in occupational therapy.

In occupational therapy, the process required for such dual attention has long been referred to as art and science. A familiar definition of occupational therapy refers to the “art and science of man’s [sic] participation…” (AOTA, 1972, p. 204). The equal importance of both perspectives was emphasized by Turpin (2007), who stated, “When occupational therapists refer to the paired concepts of art and science, they express their moral dissatisfaction with being constrained by either. In isolation, art somehow seems too soft and unquantifiable and science too hard and unyielding. The pairing of art and science expresses the complexity of occupational therapy; we are not one thing, but many” (p. 482). Kielhofner (1997) explained the implications of this dual perspective for clinical reasoning by saying, “Managing the intersection of scientific understanding and judgement with artful practice is challenging work. It requires occupational therapists to balance different ways of knowing and thinking in action” (p. 88).

Also contributing to an understanding of its complexity is the observation that action, observation and interpretation are integral to occupational therapy reasoning. Mattingly and Fleming (1994) observed that occupational therapists don’t just reason and then act but reason through action and observation. They ask their clients to do certain things in order to observe them (to collect or interpret information) and they engage in action themselves in order to collect information to help them understand how people are performing their everyday occupations. This understanding then informs further action to collect more specific information or to test their judgements about interventions or their understanding of the situation.

Reasoning in action is not simply a process of trial and error, but a specific and targeted process. Mattingly and Fleming (1994) concluded that occupational therapists compare their observations with their pre-existing “stock of basic knowledge” (p. 322) in order to make interpretations and inferences. As they stated, “observations become information only if they can be used against a backdrop of prior knowledge” (p. 322). It may be that the process Unsworth (2005) called “generalization reasoning” is the same as the linking of observations made in specific situations to a stock of prior knowledge. All three types of knowledge outlined by Higgs et al. (2001) – propositional, professional craft and personal knowledge – can contribute to this stock of prior knowledge. As occupational therapists gain experience, learning from these experiences is added to this stock of knowledge. This explains why expert occupational therapists form their judgements on the basis of “smaller bits of information” (Mattingly & Fleming, p. 323) and less (but more targeted) action than novice occupational therapists. They have a more extensive (and probably more organized) stock of knowledge from which to draw when planning action.

A model for professional reasoning in context

While models of practice provide a broad framework to assist occupational therapists in conceptualizing their work, professional reasoning is needed to determine what to do in a particular practice situation with a particular client. In order to support the use of models in practice, in this section, we present the Model of Context-specific Professional Reasoning (MCPR), a model for conceptualizing occupational therapy reasoning in context. While there are other models of professional reasoning (e.g. see Schell, 2009), we propose that other models pay insufficient explicit attention to context. For example, in describing her ecological model of professional reasoning (Schell, 2009), the only statement pertaining to context was Schell’s statement, “the therapist and the client function within a community of practice that shapes the nature, scope, and trajectory of the therapy process” (p. 324). In this chapter, we have discussed how a community of practice influences practice. However, the encounter between both clients (whether individuals or collectives) and therapists occurs within a broader organizational, legislative and policy, and cultural context. The Model of Context-specific Professional Reasoning conceptualizes professional reasoning as highly contextualized.

As discussed in the chapter so far, occupational therapists, as professionals, fulfil socially recognized roles. Within these roles, they have to make complex professional judgements under conditions of uncertainty. In occupational therapy, the complexity of decision-making relates to both the complex reasoning required of professionals in general and to the equal attention that occupational therapists pay to both physical and lived bodies.

Occupational therapy professional practice also requires both thinking and action. Occupational therapy practice includes a process of reasoned action, in which practitioners act and ask others to act in order to observe and collect information. They interpret this information using their stock of prior knowledge, which includes both context-specific information and generalized knowledge. This information is collected in a range of different ways (e.g. formal and informal assessments, interviews and discussions with clients, accessing medical information and reports from other professionals) and, as Mattingly and Fleming (1994) noted, occupational therapists seem to observe constantly. Diverse information needs to be integrated and synthesized to enable practitioners to make judgements about the services they might offer. This synthesis is not necessarily easy as the information practitioners collect can be conflicting and difficult to interpret and combine.

Occupational therapy reasoning shares features with the reasoning of other health professionals. Turpin and Higgs (2010) stated that professional reasoning: (1) is inherently complex in nature; (2) is embedded within decision−action cycles; (3) is influenced by contextual factors; (4) requires collaborative decision-making; and (5) evolves into multiple ways of reasoning as expertise increases.

Higgs and Jones (2008) also identified three core dimensions of clinical reasoning and three interactive/contextual dimensions. The core dimensions are: (1) discipline-specific knowledge, both propositional and non-propositional; (2) cognition, whereby practitioners compare more objective clinical information with their existing stock of discipline-specific and personal knowledge and interpret it with regard to client needs and preferences; and (3) metacognition. In discussing metacognition, they stated, “[practitioners] identify limitations in the quality of information obtained, inconsistencies or unexpected findings; it [metacognition] enables them to monitor their reasoning and practice, seeking errors and credibility; it prompts them to recognize when their knowledge or skills are insufficient and remedial action is needed” (p. 5). In recognition of the increasing emphasis on client-centred practice and consumer engagement in health, they included the additional dimensions of mutual decision-making, the decision-maker’s interaction with the context and the impact of the task or problem on the reasoning.

While professionals acquire discipline-specific knowledge, it is well recognized that they also develop a stock of context-specific knowledge the longer they work in one place or area of practice. This was outlined in work on the development of expertise (Benner, 1984; Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986), which proposes that professionals develop expertise through experience in particular contexts. Consequently, when they practice in a different area, people with expertise in a previous area use the thinking strategies associated with the less experienced stages until they develop experience in the new area. This suggests that context-specific knowledge is fundamental to expertise.

To summarize, the work on professional reasoning generally (and that of occupational therapists more specifically) suggests that professionals:

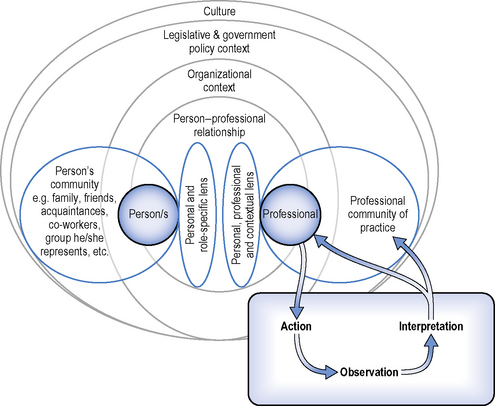

Figure 2.1 is a diagrammatic representation of our Model of Context-specific Professional Reasoning (MCPR). In this model, we have purposely centred the reasoning on the interaction between a professional and another person, to emphasize that professional reasoning is ultimately context- and person-specific. That is, it occurs in a particular time and place, with particular people and in the context of particular relationships. It may include direct contact with a person or reference to the image of a type of person (e.g. when preparing resources for populations and subpopulations).

The choice of the word person/s might appear to invite the criticism that the model only applies to work with individual clients, but this is not the case. The term person was selected, rather than ‘client’, because the model distinguished between the focus of the work (which often relates to clients) and the interaction with particular people (or images). Regarding the focus of the work, clients can include large and small groups or collectives of individuals as well as individuals and formal entities. For example, professionals such as occupational therapists might work with individual clients and their families, groups of individuals or entities such as organizations (e.g. government and non-government agencies) and companies (e.g. seeking to increase the safety of their employees). In some cases, the groups to which occupational therapists target work are whole populations or subpopulations (in such cases, these collectives are not generally referred to as clients). For example, an occupational therapist might be advocating for or engaged in developing policy that will provide needed resources to facilitate the participation of individuals with a disability (where they are working with images of people rather than specific clients).

Regardless of where the work is focused, it requires the professional to interact with particular people. These people might be clients themselves, people who have concerns for or connections with individual clients, or people who represent or are responsible for others in formal organizations such as an agency or corporation. The ultimate purpose of this interaction is for the professional to engage in action directly or to facilitate the action of others.

Regardless of whether occupational therapists are working directly with individuals, groups of individuals or through larger entities and collectives, they aim to make a positive impact upon the health and well-being of particular people − whether those people can be identified individually or are just seen as part of a larger group, entity or population. For example, an occupational therapist might be working on rehabilitation with Mary Smith to reduce impairments or promote adaptation of aspects of her environment to improve wanted participation in life roles. Alternately, the occupational therapist might be working on a population-based health promotion campaign with the aim of improving the lives of people like Mary Smith (i.e. they can’t identify which specific persons will benefit from the project).With these examples in mind, we conceptualize professional reasoning as aiming to impact upon particular people. We have used the term ‘person’ in the model to denote this.

Embedded within the model is the assumption that individuals exist within the context of relationships with others (both formal and informal). In that respect, the Model of Context-specific Professional Reasoning can be seen as influenced by a sociocultural approach. People live within broader social and cultural contexts. They are influenced by the people with whom they have direct relationships, larger communities of people and the ideas that are debated or taken-for-granted by those communities (often referred to as culture in its broader sense), and various ways that the society in which they live is structured and organized.

The model provides a diagrammatic representation of some of the contexts that surround the professional and the person/s with whom they are interacting to develop or provide a service. To simplify discussion of this complex situation, the diagram is divided into foreground and background. In the foreground of the diagram, are professionals and persons who bring particular perspectives to the encounter. Borrowing from Schell (2009), these are represented in the diagram as “lenses”. Surrounding each person engaged in the encounter is a particular community that also influences his or her perspective. For all people, these include other people that influence their lives and perspectives. In addition, surrounding professionals are professional “communities of practice” (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

In the background of this encounter, there are various layers of social context that influence the encounter. In the diagram, these are represented as: (a) the person−professional relationship, which denotes the concept that relationships between people are more than the sum of the interactions of which they are constituted; (b) the organizational context, which aims to denote the particular practice environments in which the encounter occurs; (c) the context of legislation and policy that surrounds the encounter and within which all of the key characters in the encounter live; and (d) the culture of the society.

Figure 2.1 also includes a blue box with arrows. This component of the model makes explicit the reasoning in action that occupational therapists have been observed to use. Each aspect of the diagram is discussed in more detail.

Foreground features

In most practice scenarios, occupational therapists and persons/clients engage in some sort of relationship organized around the provision of a specific service. Both professionals and the person/s with whom they work bring their own particular perspectives to the encounter. We have borrowed the concepts of the personal and professional lenses from Schell (2009, p. 324) and added our own concept of the various roles the person and professional might be fulfilling and the professional’s understanding of the specific context in which the encounter is taking place. Therefore, we have called these perspectives ‘personal and role-specific’ and ‘personal, professional and contextual’ lenses. The former role-specific lens might refer to lenses such as client, carer or policy developer. The latter denotes that professionals’ perspectives are influenced by: (a) personal experiences and ways of understanding the world; (b) their identity and experience as a member of a particular profession (e.g. an occupational therapist) and the way they have internalized the values and beliefs of their professional community; and (c) their understanding and experience of their particular role within a specific practice context and the culture of that practice context.

These perspectives will be influenced by the personal qualities of each person. This ‘personal lens’ includes each person’s beliefs, values, intelligence, embodied sense and abilities, and life experiences and living situation (Schell, 2009, p. 324). In addition, people bring perspectives that are shaped by their roles within the encounter. In many occupational therapy scenarios, the people engaging in the encounter in the role of client will bring particular expectations related to that role. For example, they might have particular expectations for the professional’s level of expertise and the degree of collaboration that should occur. The occupational therapist will also bring expectations relating to his or her own behaviour and that of clients within the particular practice context in which the encounter is taking place. In addition, a professional’s role will be shaped by the particular practice context in which the encounter occurs. How they approach and perceive the specific situation will be influenced by their knowledge of what is done in that organization and how.

Both the person and the professional are also influenced by their respective communities. In the case of people receiving services (clients), they will have a range of experiences and formal and informal relationships with the people connected to them. These will all influence the perspectives they bring to the encounter – both their personal perspective and their expectations relating to the role of client – and the degree to which they are likely to follow recommendations that the professional might make. These relationships will also influence the personal and material resources that are available to clients and will impact upon what can be done (pragmatic reasoning regarding intervention/service delivery options). For example, the number of people a family’s financial resources needs to support will impact upon whether services that carry a financial cost can be offered and how often the relevant family members can afford to attend the service (i.e. cost of service, transport, time off from work, etc.). An intervention for a disabled person living in a group home might need commitment from support workers to carry out or supervise what has been recommended. Any recommendations for change to workplaces will need to be appropriate to the culture of the workplace (management and workers) and the processes required to undertake their core business.

As with their clients, professionals are also surrounded by their own communities, which will influence their personal perspectives. In addition to this, they are part of communities of practice, such as the local, national and international community of occupational therapists, which influence their professional perspective. As a profession, occupational therapy has its own unique knowledge base, values and perspectives and these influence the perspectives each professional will bring to an encounter with clients. It influences what kinds of information they seek and how they collect it, how they interpret information, and what kinds of interventions and services they feel they can offer.

Background features

So far we have discussed the part of the diagram that is foregrounded. Now we turn to the background of a broader, multilayered context within which an encounter occurs. In the model, we have identified four of the major layers of context that surround any encounter between professionals and service users.

The first is the relationship between the people involved in the encounter. While each individual will bring their particular lens to the encounter, the relationships that develop between the various people involved will also influence the process and outcome of the encounter. Relationship is specified as a particular background feature because the relationships that people develop can influence the decisions that are able to be made. For example, an occupational therapist might be working with a particular organizational client. He or she might have built a facilitatory relationship with a particular manager and be able to make certain recommendations and have a high level of confidence that they would be implemented. However, if a new person came into that position, because they would have a different relationship, the recommendations the occupational therapist might make are likely to differ.

The importance of relationships between professionals and clients is well recognized as affecting the outcome of their encounters (Price, 2009). Examples of these person−professional relationships include relationships with individual clients and their significant others, with groups of clients, with people in management or supervisory positions who are responsible for a group of workers or the management practices of a company, and with elders or leaders of particular community groups. These relationships are central to occupational therapy philosophy as occupational therapists aim to work with people rather than doing things to them. It is through these different types of relationships that they aim to influence the health and well-being of individuals, groups and populations.

The next layer of context relates to the organization in which the person–professional interaction occurs. We have called it organizational context because most occupational therapy work is undertaken within a particular practice context. Whether the occupational therapist is being paid or doing the work in a voluntary capacity, they are usually either providing services directly through particular organizations or working with particular organizations to influence their provision of services and resources. The term organization is defined as “a body of persons organized for some end or work” (Macquarie Dictionary, 1985, p. 1202). We are using the term in this broad way to denote a range of different types of organizations such as government and non-government agencies, corporations, service delivery organizations, incorporated bodies, etc.

Organizations are important to consider as a context in which the person–professional encounter occurs (and therefore where professional reasoning is required) because they have a particular culture that influences what work is done and how it is done. This culture shapes occupational therapy practice at subconscious and conscious levels. That is, occupational therapists might develop routine ways of seeing and doing things in a particular context or they might be consciously aware of the constraints and demands that the practice environment places on their practice. Organizations are established for a particular purpose and there is an expectation that the people working for them or with them will be instrumental in fulfilling that purpose. These expectations will help shape the professional lens. Similarly, clients and others will come with particular expectations about that organization regarding the type and quality of services or assistance provided. These expectations form part of their role–specific lens.

The next layer of context relates to the society in which the encounter takes place. Larger societies have formal legislative and government processes that determine the rules of that society. In parliamentary democracies, laws are made through acts of Parliament and enforced by legal processes (e.g. courts) and regulators, and organizations such as police forces. Subgroups might also exist in societies, in which persons hold recognized positions and provide leadership and governance to that subgroup such as elders of indigenous groups. Both professionals and the people they work with have to abide by the laws of the society and will be influenced by the policies (and subsequent services and practices) developed and/or funded by the government.

The final layer, which influences all of those layers within it, is the culture of the society. Cultural (and subcultural) beliefs and practices pervade the lives of people and influence their behaviour. They also influence the expectations and social mores relating to relationships between professionals and clients, as well as the organizations that are developed (and allowed) and the laws and policies that are created. Cultural beliefs and practices are often held and enacted at a subconscious level, as people who have grown up in those cultural contexts will have internalized many values and beliefs. They become taken-for-granted assumptions. Often, people only become aware of those values and beliefs when they are confronted with situations that do not align with those values and beliefs. This might occur because of a particular event or circumstance, through moving from one culture to another, or when subcultural values do not align with those of the dominant culture or other subcultures.

Occupational therapy reasoning and action

In addition to the multiple layers that surround person and professional, specific features of occupational therapy reasoning are included. This is presented in an additional box in the lower right of the diagram in Figure 2.1. This box is informed by Mattingly and Fleming’s (1994) observations and interpretations of occupational therapy clinical reasoning. They emphasized that action is an integral part of occupational therapists’ clinical reasoning and linked this to the profession’s roots in the philosophical perspective of pragmatism (see the work of John Dewey, William James and Charles Sanders-Pierce). Other authors have also noted the influence of this tradition (Ikiugu, 2007).

Mattingly and Fleming (1994) noted that occupational therapists often reason through action – both their own and the action of others. Their study participants (occupational therapists) asked their clients to do something so that they could observe, with precision, how the client undertook these tasks. They also acted themselves (e.g. performed a formal assessment), in order to observe the outcome and, on the basis of their interpretations of those observations, make judgements. Consistent with the work of Higgs and colleagues, Mattingly and Fleming found that occupational therapists interpreted their observations by comparing them with their stock of knowledge (both theoretical and practice-based). This process of interpretation enabled them to make judgements about the clinical situation and to plan further action. The experience gained from these cycles of action, observation and interpretation was added to the professional’s stock of knowledge and became part of the information against which further action cycles were interpreted.

The knowledge gained from these action cycles can also be used to change practice for more than just the individual practitioner. Walker (2001) emphasized that communities of practice both influence and are influenced by their members. This influence might occur in a formal sense as occupational therapists publish their work for others to read but it can also influence practice at the local level. Referring to physicians, Parboosingh (2002) claimed that these professionals “naturally form COP [communities of practice]” when working in the same area and that members of this community “contribute to the collective pool of evidence-based knowledge, drawn from the peer-reviewed literature, as well as tacit knowledge and practical wisdom derived from practice experience” (p. 231). The same could be said of occupational therapists. They spend time (formally and informally) sharing their knowledge and experiences and engaging in joint problem solving. Mattingly and Fleming (1994) stated that these processes expanded their stock of knowledge vicariously.

Occupational therapy professional reasoning and models of practice

The Model of Context-specific Professional Reasoning highlights the complexity of factors that influence professional reasoning. These factors can relate to the personal qualities and experiences of the professional and his or her expectations about their professional role, the perspective of the discipline to which the professional belongs, personal aspects of the client/s and the expectations of the professional’s role that they bring to the encounter, the nature of the encounter between clients and professionals and the organizational, legislative and government policy, and cultural contexts in which the client−professional encounter occurs (which all shape professional role expectations). All of these factors interact to create a unique situation for every client−professional encounter.

An important aspect of the model is the professional community of practice (which can be discipline-specific or multidisciplinary, e.g. multi- or transdisciplinary teams). Professionals develop their understanding of their particular professional discipline through professional socialization and the acquisition of the specific knowledge base unique to each profession. Professionals maintain their professional identities through access to and identification with their community of practice. This could be done directly by having contact with other members of the community of practice (e.g. through workshops and special interest groups or just through contact with co-workers) or less directly by reading publications produced by members of the community of practice and identifying with that community (e.g. by working with members of other professions and defining oneself as an occupational therapist and, therefore, different from the other professions because of particular professional values and perspectives that one shares with occupational therapy).

While professionals also belong to other communities of practice, such as multidisciplinary teams working together to provide a service to a particular subpopulation or group, the values and perspectives of the professional group to which they belong often shape their understandings in a variety of ways, of which they might not be aware because it “represents the unquestioned norm” (Trede & Higgs, 2008, p. 32) of their professional group. Unless they are able to make these assumptions overt, these norms can be difficult to examine and critique. Without such examination, the value of such norms cannot be established (either positively or negatively).

One of the ways that a shared vision of the occupational therapy community of practice is available is through its conceptual models of practice. Each of the models of practice discussed in this book presents a particular way of organizing and describing occupational therapy theoretical assumptions and values (the shared vision) for the purpose of guiding practice. In this regard they all share the perspectives and values that characterize occupational therapy as a profession and distinguish it from other professions. Therefore, the core of occupational therapy is encapsulated within the commonalities of the models. However, each model also emphasizes different aspects of the shared vision to different degrees. This variation probably relates to a combination of the different practice environments for which some of the models were originally developed, sociocultural differences relating to the country in which or for which they were developed, the time in occupational therapy’s history in which they were developed or revised, and the particular philosophical perspectives that the authors chose to present or emphasize.

Trede and Higgs (2008) stated that, “models can be thought of as mental maps that assist practitioners to understand their practice” (p. 32). This is the way that we are conceptualizing them in this book. By exploring the different models of practice in detail in the one text, we hope to provide readers with a resource that helps them to compare and contrast the different occupational therapy models and to select models that support the professional reasoning they need to do in specific contexts at specific historical times. We also hope that this condensed presentation of occupational therapy models of practice helps readers to distil the essence of occupational therapy philosophy.

The chapters that follow present nine occupational therapy conceptual models of practice. They were all developed to guide practice by providing a systematic way to organize many of the core concepts of occupational therapy. The advantage of using conceptual models to guide practice is that they provide a systematic and comprehensive way to conceptualize practice. Often they are used in conjunction with other frameworks, which mostly provide greater detail about interventions and techniques relevant to a particular practice area. As discussed in Chapter 1, these are often referred to as frames of reference and frequently contain information that is not specific to occupational therapy. Conceptual models of practice, however, are specific to occupational therapy and contain the profession’s core concepts. For each model, the core concepts and an overview of its history are described, and a memory aid is provided to facilitate use of the model in practice. In addition, the major references for each model are also provided As this book aims to provide an overview of some of the major occupational therapy conceptual models of practice, readers are encouraged to develop a more in-depth understanding of the models that they feel are most relevant to their own practices.

Summary

In this chapter, we discussed the nature of professional practice. We presented professions as groups that are recognized within society and are provided both obligations and privileges. Professions are afforded autonomy and, often, higher levels or remuneration whilst being expected to have a unique knowledge base, a code of ethics and engage in self-regulation. The profession to which an individual belongs operates as a community of practice in which the individual is surrounded by a larger professional body that shapes and is shaped by their learning about the culture of the profession.

Professionals are expected to fulfil particular roles in society. They generally work under conditions of uncertainty and are required to engage in professional reasoning to make judgements about what action/s to take in a particular circumstance. Occupational therapists value both art and science in their understanding of the needs of clients and their expectations about the interventions or services that they can offer. They place equal value on both when making decisions about what to do in their professional role.

Action is central to occupational therapy practice and an integral part of occupational therapists’ decision-making. That is, they often think in and through action. Such action always occurs within a particular context, which shapes and is shaped by these decisions and actions. Thus, occupational therapy reasoning and decision-making is always context based.

In this chapter, we presented a model for understanding the context-specific nature of occupational therapy professional reasoning. The Model of Context-specific Professional Reasoning aims to assist occupational therapists to consider the range of contextual features that impact upon their reasoning. This model conceptualizes occupational therapy professional reasoning as:

One of the ways that the occupational therapy community of practice shapes practice is through models of practice. These models are a level of theory that specifically aims to guide practice. In the chapters that follow, we present nine occupational therapy models of practice. For each, we present the major concepts as outlined in their most recent form, a discussion of their historical development, a list of major publications (these are not meant to be exhaustive but to provide a starting point for readers who wish to investigate the model in more detail), and a memory aid to assist occupational therapists when using the model in their practice.

AOTA. Occupational therapy: Its definition and function. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1972;26:204.

Benner P. From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1984.

Blair S.E.E. Role. In: Jones D., Blair S.E.E., Hartery T., Jones R.K., editors. Sociology and occupational therapy: An integrated approach. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998:41-53.

Blair S.E.E., Robertson L. Hard complexities – soft complexities: An exploration of philosophical positions related to evidence in occupational therapy. Br. J. Occup. Ther.. 2005;68(6):269-276.

Carr W. For education: Towards critical educational inquiry. Buckingham, UK: The Open University, 1995.

Coles C. Developing professional judgement. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof.. 2002;22:3-10.

Dreyfus H., Dreyfus S. Mind over machine: the power of human intuition and expertise in the era of the computer. New York: The Free Press, 1986.

Evenson M. Fieldwork: The transition from student to professional. In: Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Boyt Schell B.A., editors. Willard & Spackman’s occupational therapy. eleventh ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:252-261.

Fish D., Coles C. Developing professional judgement in health care: Learning through the critical appreciation of practice. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 1998.

Fleming M.H. The therapist with the three-track mind. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1991;45:1007-1014.

Higgs J., Jones M. Clinical decision making and multiple problem spaces. In: Higgs J., Jones M., Loftus S., Christensen N., editors. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. Philadephia, PA: Butterworth Heinemann; 2008:3-17.

Higgs J., Titchen A., Neville V. Professional practice and knowledge. In: Higgs J., Titchen A., editors. Practice knowledge and expertise in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 2001:3-9.

Hocking C., Ness N.E. Minimum standards for the education of occupational therapists. Forrestfield, Australia: World Federation of Occupational Therapists, 2002.

Hunink M.G.M., Glasziou P.P., Siegel J.E., Weeks J.C., Pliskin J.S., Elstein A., et al. Decision making in health and medicine: Integrating evidence and values. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Ikiugu M.N. Psychosocial conceptual practice models in occupational therapy: Building adaptive capability. St Louis, MI: Mosby, 2007.

Iwama M. Culture and occupational therapy: meeting the challenge of relevance in a global world. Occup. Ther. Int.. 2007;4(4):183-187.

Kielhofner G. Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy, second ed. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis, 1997.

Lave J., Wenger E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Macquarie Dictionary. Revised ed. Macquarie Library, Dee Why, NSW. 1985.

Mattingly C. The narrative nature of clinical reasoning. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1991;45(11):998-1005.

Mattingly C., Fleming M.H. Clinical reasoning: forms of inquiry in a therapeutic practice. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis, 1994.

Parboosingh J.T. Physician communities of practice: Where learning and practice are inseparable. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof.. 2002;22:230-236.

Price P. The therapeutic relationship. In: Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Boyt Schell B.A., editors. Willard & Spackman’s occupational therapy. eleventh ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:328-341.

Rogers J.C. Clinical reasoning: The ethics, science, and art. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1983;37:601-616.

Rogers J.C., Masagatani G. Clinical reasoning of occupational therapists during the inital assessment of physically disabled patients. Occup. Ther. J. Res.. 1982;2:195-219.

Sackett D.L. Evidence based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Schell B. Professional reasoning in practice. In: Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Boyt Schell B.A., editors. Willard & Spackman’s occupational therapy. eleventh ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:314-327.

Schell B., Cervero R. Clinical reasoning in occupational therapy: An integrative review. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1993;47:605-610.

Trede F., Higgs J. Collaborative decision making. In: Higgs J., Jones M., Loftus S., Christensen N., editors. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. third ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 2008:31-41.

Turpin M. The issue is… Recovery of our phenomenological knowledge in occupational therapy. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 2007;61(4):481-485.

Turpin M., Higgs J. Clinical reasoning and EBP. In: Hoffman T., Bennett S., Bennett J., Del Mar C., editors. Evidence-based practice across the health professions. Melbourne, VIC: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:300-317.

Unsworth C. The clinical reasoning of novice and expert occupational therapists. Scand. J. Occup. Ther.. 2001;8:163-173.

Unsworth C. Using a head-mounted video camera to explore current conceptualizations of clinical reasoning in occupational therapy. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 2005;59:31-40.

Walker R. Social and cultural perspectives on professional knowledge and expertise. In: Higgs J., Titchen A., editors. Practice knowledge and expertise in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 2001:22-28.