4 Person-environment-occupation models

As with most occupational therapy models, the models reviewed in this chapter centre on the influence of person, environment and occupation on people’s abilities to act in the everyday world. However, these models emphasize the importance of the environment to a greater extent than the models reviewed in the previous chapter (with the proviso that the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (OPMA) could have been placed in this chapter). Baum and Christiansen (2005) identified these types of models as person, environment, occupation or PEO models and Brown (2009) described them as ecological models. They have also been described as transactional models as they emphasize the mutually influencing transaction that occurs between person and environment when engaged in occupation. The three models reviewed in this chapter are the Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model by Christiansen and Baum, the Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) model by Law and others, and the Ecology of Human Performance (EHP) by Dunn and others.

Person-Environment-Occupation- Performance (Peop) Model

We have placed this model first in the chapter as it appears to provide a bridge between the Occupational Performance (OP) model and ecological models. It acts as a bridge in sharing a trend with OP to analyze in detail the capacities of the individual. However, whereas OP provides comparatively little attention to the environment, the PEOP model provides a similar level of detail for analyzing the environment as it does for the person. The PEOP model was listed as an ecological model by Brown (2009). However, as discussed later in this chapter, this model differs from the other two models presented in this chapter through its conceptualization of the relationship between person, environment and occupation. In discussing this relationship, the other two models emphasize that person, environment and occupation should not be considered separately. The PEO emphasizes a transactive relationship between the three (rather than interactive) and EHP presents context as something through which person and occupation should be seen. Although similar to some of the other occupational therapy models, PEOP conceptualizes person and environment as joined by occupation (and performance and participation). That is, occupation is the medium through which person and occupation connect. In comparison with PEO, this model is interactive rather than transactive.

Main concepts and definitions of terms

The PEOP model is described as “a client-centred model organized to improve the everyday performance of necessary and valued occupations of individuals, organizations, and populations and their meaningful participation in the world around them” (Baum & Christiansen, 2005, p. 244). This definition demonstrates the importance of two concepts: occupational performance and participation in daily life. While many occupational therapy models explicitly focus on the enhancement of occupational performance as their main goal, this model explicitly identifies enhancing participation as a second primary goal. This model makes explicit that the goal of occupational performance is to enable participation in the social, cultural, financial and political world in which people and organizations exist. Therefore, a major contribution of the model is its acknowledgement that occupational performance might not be an end in itself but might gain meaning through its role in facilitating participation.

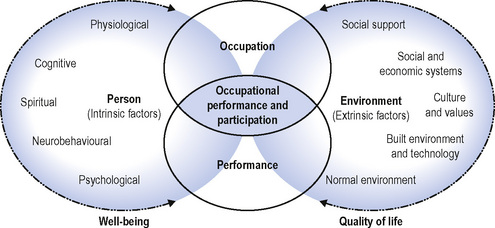

The focus of the model is the complex interaction between a person and his or her environment, which influences occupational performance and participation. This interaction forms the basis for occupation, in that intrinsic and extrinsic factors, respectively, form the foundation for what people do. Intrinsic factors (neurobehavioural, physiological, cognitive, psychological and emotional, and spiritual factors) and extrinsic factors (built, natural and cultural environments; societal factors; social interactions and social and economic systems) can “support, enable or restrict” (Baum & Christiansen, 2005, p. 244) performance by individuals, organizations and communities.

As suggested by its title, the four components of the model are person, environment, occupation and performance. Figure 4.1 shows the most recent diagram available at the time of publication. One useful way to think about this model is to interpret the four components (and diagram) as if lying in three dimensions. Upon a foundation of person and environment (first layer) lies occupation and performance (second layer) and on top of these are occupational performance and participation (third layer). First, person and environment, which interact in a mutually influencing way, form the foundation for what people do. The concept of ‘person’ includes the various capacities (neurobehavioural, psychological, etc.) that a person might have, which can influence what a person can and is inclined to do. These are referred to as intrinsic factors. The environment also has features that can affect performance (extrinsic factors). The extrinsic factors include physical, cultural and societal aspects of the context that surrounds them.

FIG 4.1 Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model.

Christiansen CH, Baum CM, Bass-Haugen J. Occupational Therapy: Performance, Participation and Well-Being, Third Edition, Thorofare, NJ: SLACK Incorporated; 2005. Reprinted with permission from SLACK Incorporated.

The second layer in the PEOP model comprises the components of occupational performance, that is, occupation and performance. The model makes clear distinctions between the concepts of occupation, performance and occupational performance, the last located in the third layer. Occupations were defined by Christiansen and Baum (2005) as “human pursuits that (a) are goal-directed or purposeful, (b) are performed in situations or contexts that influence how and with whom they are done, (c) can be identified by the doer and others, and (d) have individual meaning for the doer as well as shared meaning with others” (p. 5). They proposed that occupations can be classified according to what is done and how, why, where and when it is done. However, it is important to note here that occupation is not the same as performance. Where occupations and actions are done, performance refers to the actual doing of them. As Baum and Christiansen (2005) stated, “To be able to do requires that an action or a task be performed. Performance can come from either capacity intrinsic to the individual or by support provided by the environment or a combination of both.” (p. 246.)

The top layer of the model, and the culmination of the previous layers, comprises occupational performance and participation. In the diagram provided, occupational performance and participation result where occupation and performance overlap. As Baum and Christiansen (2005) stated, “when occupation and performance are joined in the term occupational performance, it describes the actions that are meaningful to the individual as he or she cares for him- or herself, cares for others, works, plays, and participates fully in home and community life” (p. 246). In making the distinction between occupation, performance and occupational performance, they emphasized the meaning and purpose of occupational performance in the context of people’s roles. Therefore, their statement that occupational performance is “the central construct of participation” (p. 246) places occupational performance within the context of meaningful and purposeful participation in an individual’s broader societal context.

Baum and Christiansen’s hierarchy of occupation-related behaviours and supportive abilities (2005; Christiansen & Baum, 1997a) is central to understanding the distinction between occupation and performance and occupational performance. This hierarchy places roles, occupations, tasks, actions and abilities in order from highest to lowest in complexity. As “occupations have a purpose” (Baum & Christiansen, 2005, p. 252), the top three levels on the hierarchy – roles, occupations and tasks – would be conceptualized in the occupation part of the model because they are linked to purpose. The next level in the hierarchy – actions – would be attended to in the performance part of the model, because they do not have a separate purpose. The lowest level of the hierarchy – abilities – would be considered in the person part of the model, as they lie within the person (as intrinsic factors). All of these occupation-related behaviours occur within a specific context or environment, which can support, enable or restrict the performance of occupations and tasks and, hence, affect participation in everyday life.

The model provides details of both person and environment, located in the first layer. A major technique in occupational therapy practice is the analysis of both person and environment for the purpose of facilitating occupational performance and participation. Therefore, this model provides substantial detail to guide occupational therapists in undertaking such analysis. The factors that contribute to a person’s capacities are called intrinsic factors and those factors that relate to the context of occupational performance and participation are called extrinsic factors.

Intrinsic and extrinsic factors

The intrinsic factors listed in the model (Baum & Christiansen, 2005) are physiological, cognitive, spiritual, neurobehavioural and psychological.

The external factors listed are social support, social and economic systems, culture and values, the built environment and technology, and the natural environment. The various external factors influence occupational performance and participation by placing demands or providing affordances.

The internal and external environments are not inherently facilitatory or inhibitory. Occupational performance and participation are dependent upon the interaction between the internal and external factors in relation to the demands of the occupation being performed. This model provides substantial detail about both internal and external factors to support occupational therapists to analyze the interests, skills and capacities of the person, the demands of the environment and how they interact to facilitate or inhibit occupational performance and participation.

Historical description of model’s development

The PEOP is presented within the context of a larger text (as with CMOP-E, presented in the next chapter). The text, called Occupational Therapy: Performance, Participation and Well-being (Christiansen et al., 2005) relates to occupational therapy more generally and takes the reader through the fundamental assumptions of the profession relating to occupation before presenting the model. Thus, the PEOP forms one part of Christiansen’s and Baum’s broader conceptualization of occupation and occupational therapy.

This model commenced its development in 1985 (Baum & Christiansen, 2005). In 2005 the model was called Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) and it has undergone substantial changes and development in the three editions that were available at the time of publication. In each edition, it was called something different. The 1991 version was called a “Person-Environment-Performance” framework (Christiansen, 1991, p. 18) and was not referred to as a model. In 1997, it was called the “Person-Environment Occupational Performance Model” (Christiansen & Baum, 1997a). In 2005, it was called the “Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance Model” and provided with the acronym PEOP. The concepts of person, environment and performance appear to have remained the fundamental components of the model but the emphasis on occupation in the title as a separate concept has only recently emerged.

The distinction between occupation, performance and occupational performance is evident in all three editions of the model. The distinction between these concepts can be traced back to the model’s use of Nelson’s 1988 work, in which he distinguished between occupational form and performance. Christiansen (1991) stated, “all the elements comprising the context of the occupation are what Nelson (1988) terms the form of occupation. Occupational performance consists of the doing of occupation.” (p. 27, italics in original.) In an adaptation of Nelson’s work, Christiansen conceptualized occupational form as “the objective context of occupation consisting of: materials, environmental surround, other humans involved, temporal dimension, and sociocultural reality derived from social or cultural consensus” (p. 26).

In the first version, a binary distinction appears to have been made between the doing (performance) and a second concept (Christiansen’s adaptation of occupational form) that includes what is done, the context in which it is done and the meaning of the doing to an individual. In this way, the first edition appears to have distinguished between performance and a broad conceptualization of occupational form, with the latter being ascribed meaning by an individual and occurring within a particular content.

In the second edition, a trio of concepts was presented. These were person, environment and occupational performance. This version emphasized that the performance of occupation is affected by a complex array of factors that influence performance, “as well as the many dimensions of occupation” (Christiansen & Baum, 1997a, p. 49). Christiansen and Baum stated, “Occupational performance consists of the ‘doing’ of occupation; whereas occupational form concerns the context of the doing” (1997b, p. 6). In the second edition, the concept of occupational form has been explicitly presented as involving the interaction between person and environment. This is consistent with Christiansen’s earlier interpretation of Nelson’s concept of occupational form to include the meaning that the occupation has for an individual. In the second edition, the concept of occupation is like the invisible focus of the model. Using the metaphor of the window presented in the Introduction, occupation is like the window through which one might look without making the window itself explicit in the description of what one sees. Consequently, the concept of occupation was not specifically included in the diagrammatic representations of the model but was integral to it, in that it was present in all three parts of the model – person, environment and occupational performance.

In the first and second editions, the concept of occupational form appears to have been separated into person and environment (conceptualized as mutually influencing) and contrasted with performance. By the third edition of the model, the separation of concepts is most obvious. In that version, the capacities of an individual and the context in which something is done (sociocultural and physical environment) are presented as separate but mutually influencing. They provide the background to the occupation and its performance, which combine to result in occupational performance and participation.

In the second edition, the model emphasized the importance of occupational performance to self-identity and a sense of fulfilment. (However, this emphasis might have become lost in the most recent edition or at least become subsumed under the concept of participation.) In the second edition, Christiansen and Baum (1997a) stated, “over time, these meaningful experiences permit people to develop an understanding of who they are and what their place is in the world” (p. 48).

This focus on self-identity, combined with the detailed explication of personal factors such as motivation, values and meaning, emphasizes the biopsychosocial nature of occupational therapy practice, as conveyed in this edition of the model. This focus is consistent with the link that is made between occupational performance (highlighted as function rather than impairment) and well-being (rather than just health), which are also consistent with a biopsychosocial approach to health. The second edition also provided a table showing the relationship between the “intrinsic performance enablers” that the model conceptualized as factors intrinsic to the person and the well-accepted occupational therapy concept of “performance components”. These intrinsic factors remained present in the third edition of the model and distinguish it from other PEO models such as the model published by Law et al., described later in this chapter.

In all three versions of the PEOP model (with various different names), the model is linked to both a hierarchy of occupational performance and the WHO classification of the time. In the 1991 version, this hierarchy is presented (from lowest to highest) as activities, tasks and roles. In the second and third editions (1997 & 2005), the hierarchy presents abilities, actions, tasks, occupations and roles. The first and second editions of the model are linked to the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH) and the third edition to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

Summary

The PEOP is the third edition of the model of practice created by Charles Christiansen and Carolyn Baum. The model conceptualizes the focus of occupational therapy as occupational performance and participation. It provides guidance for practice by breaking down these concepts into the components of occupation and performance and by identifying the factors internal to the person and within the environment that influence occupational performance and participation. All four components of the model are seen as separate but interacting. The PEOP model has similarities with the OP model through the way it breaks down factors internal to the person. However, its focus on the environment and the external factors that influence occupational performance and participation are more extensive than in the OP model. Therefore, it has been described as a person, environment, occupation model.

Memory aid

See Box 4.1.

BOX 4.1 Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model memory aid

What do these people want or need to do in their daily lives (occupation) and can these tasks, occupations and roles be done (performance) successfully by these people in the current context (occupational performance and participation)?

What do these people want or need to do in their daily lives (occupation) and can these tasks, occupations and roles be done (performance) successfully by these people in the current context (occupational performance and participation)? What roles (social responsibilities & privileges) do these people have and want to or intend to continue with?

What roles (social responsibilities & privileges) do these people have and want to or intend to continue with? What occupations have meaning for these people and how would it affect their roles if they were unable to perform them?

What occupations have meaning for these people and how would it affect their roles if they were unable to perform them?| Intrinsic factors | Extrinsic factors |

|---|---|

| What factors (performance enablers) intrinsic to these people (person) affect their capability to perform specific occupations in context? | What factors extrinsic to these people (environment) affect their capacity to perform specific occupations in context? |

| How do these factors support, enable or restrict the performance of roles, occupations, tasks & actions? | |

| Checklist | Checklist |

| Neurobehavioural factors | The built environment |

| Physiological factors | The natural environment |

| Cognitive factors | The cultural environment |

| Psychological and emotional factors | Societal factors |

| Spiritual factors | Social interaction |

| Social and economic systems |

Baum C., Christiansen C. Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance: An occupation-based framework for practice. In: Christiansen C.H., Baum C.M., Bass-Haugen J., editors. Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being. third ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2005:243-259.

Christiansen C. Occupational therapy: Intervention for life performance. In: Christiansen C., Baum C., editors. Occupational therapy: Overcoming human performance deficits. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1991:3-43.

Christiansen C., Baum C. Person-Environment-Occupational Performance: A conceptual model for practice. In: Christiansen C., Baum C., editors. Occupational therapy: Enabling function and well-being. second ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1997:47-70.

Christiansen C., Baum C. Understanding occupation: Definitions and concepts. In: Christiansen C., Baum C., editors. Occupational therapy: Enabling function and well-being. second ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1997:3-25.

Person-Environment-Occupation Model of Occupational Performance

The next two models presented in this chapter are informed by the concepts relating to human ecology. Both models were published in the mid-1990s, within 2 years of each other. The first model of practice presented is the Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) model (Law et al., 1996). As the name suggests, the major concepts in this model of practice are person, environment and occupation, which provide a way of understanding occupational performance when considered together. The concept of person-environment-occupation fit is used to outline the relationship between these different elements. When the three ‘fit’ together well, it enhances occupational performance. However, when there is a poor alignment between the three, occupational performance is reduced.

Main concepts and definitions of terms

This model of practice was based on the literature on human ecology at the time of its publication. Human ecology is concerned with the relationship between human beings and their environment. As is evident in the models reviewed in this book, attention to the relationship between person and environment was a consistent feature in publications about occupational therapy models during the 1990s (both those developed during this time and the 1990s versions of those with multiple editions). This 1990s emphasis on understanding the person in the context of their environments probably represents the crystallizations of ideas that had been percolating during the 1970s and 1980s. It constitutes a move away from a biomedical model of health to a biopsychosocial model, where individuals are seen within their broader context (the broader systems that surround them).

PEO conceptualizes the relationship between the person and the environment as “transactive” (Law et al., 1996, p. 10) rather than interactive (as with PEOP). The distinction between these two concepts relates to whether person and environment are conceptualized as distinct entities that could be studied separately or whether they should be examined together. An interactive approach would take the former position and consider the two as separate entities that are able to be measured separately and that influence the other in a cause and effect way. As Law et al. explained, “An interactive approach allows behaviour to be predicted and controlled, by influencing change at the level of an individual or environmental characteristic” (p. 10). In contrast, a transactive approach presents the person and environment as interdependent and proposes that a person’s behaviour cannot be separated from the context within which it occurs (including temporal, physical and psychological factors). Therefore, occupational performance is a context-, person- and occupation-specific process. That is, it is the result of particular people doing particular things in particular times and places.

The relationship between person and environment is understood to be mutually influencing. As Law et al. (1996) stated, “a person’s contexts are continually shifting and as contexts change, the behaviour necessary to accomplish a goal also changes” (p. 10). Therefore, rather than person and environment being examined separately, in a transactive approach, an event becomes the unit of study. As such, the observable features of the environment in which the event took place would be investigated as well as the event’s meaning to those participating. This process provides for a rich understanding of the interconnectedness of person and environment and helps to provide an understanding of how a person’s behaviour shapes and is shaped by the environment.

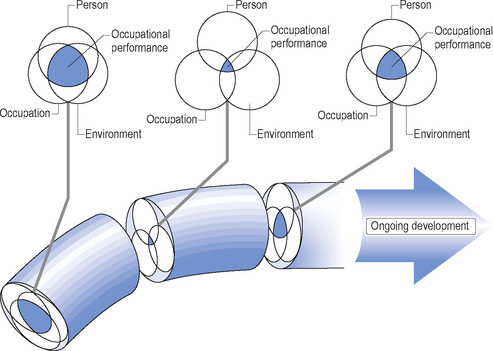

It is important within this model to understand the distinction made between interactive and transactive approaches to the person–environment relationship because the diagram of three overlapping circles (person, environment and occupation), which has probably become most associated with this model, could be misconstrued as representing an interactive rather than transactive approach (because it presents person, environment and occupation as separate but overlapping entities). However, in its published form, a three-dimensional atom-like diagram was presented, which makes the interconnectedness of these three elements clear (Figure 4.2). The diagram shows three interconnected components − environmental supports and barriers, individual skills, and occupational demands − surrounding occupational performance. Occupational performance is considered to be the “outcome of the transaction of the person, environment and occupation. It is defined as the dynamic experience of a person engaged in purposeful activities and tasks within an environment.” (Law et al., 1996, p. 16.)

FIG 4.2 Person-Environment-Occupation atom diagram.

From Law M., Cooper B., Strong S., Stewart D., Rigby P., Letts L., The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance, 1996, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 9–23. Reprinted with the permission of CAOT Publications ACE.

The first component of the model that we will discuss is person. The biopsychosocial understanding of the person is evident in discussions where Law et al. (1996) explain that occupational performance can be measured both objectively and subjectively. That is, there are features that can be observed and recorded in an objective way as well as features that relate to the experiences of the performer. The authors advocated that the latter be measured through methods such as self-report.

The changing nature of subjective experience and views of self is central to the concept of the person in this model. The person is presented as “a dynamic, motivated and ever-developing being, constantly interacting with the environment” (p. 17). People change over time as the environments surrounding them change. They change in their attributes, characteristics, abilities and skills and in the ways they think and feel about themselves. Their sense of who they are and what they are capable of develops and changes as they interact with the specific environments that surround them.

Consistent with the richly connected and contextualized view of the person is a broad definition of environment. As Law et al. (1996) stated, “the broad definition gives equal importance to the considerations of the environment” (p. 16). While occupational therapists have traditionally emphasized the influence of the physical environment on what people do and how they do it, this model makes explicit that a range of environmental considerations are equally important in influencing human behaviour and activity. While this broad concept of the environment is consistent with other models published in the 1990s, its uniqueness lies in its emphasis on the transactive relationship between the environment and person. The only other model that emphasized this degree of interconnectedness was the Ecology of Human Performance (Dunn et al., 1994).

The model outlines five aspects of the context surrounding the person − cultural, socioeconomic, institutional, physical and social − that shape and are shaped by that person. For example, culture shapes what people believe and how they see the world. This, in turn, shapes how they think about themselves and what they might want and/or are expected to do. However, individuals’ views of the world and of themselves are also dependent upon the degree to which each individual internalizes the views of the culture and the people surrounding them. What they actually do, then, influences and is influenced by the environment within which they act. Their socioeconomic circumstances will also influence their perception of what they can and can’t do as well as their access to resources. Just as a person grows and ages and changes in their skills, abilities, character and experiences, so too their circumstances are likely to change over the course of their lives. Environments can change because people physically relocate; change their roles, habits and routines; change their social and cultural groupings, etc. or because local, national and world circumstances change. For example, the environment surrounding a person living at the beginning of the twentieth century will differ greatly from that of a person living during the twenty-first century.

The third aspect of the model considers what people do within their environmental contexts. While this is called occupation in the model’s name, Law et al. (1996) considered three aspects of human action – activity, task and occupation – under this category. They presented these three concepts as “nested within each other” (p. 16) and claimed that they drew upon the work of Christiansen and Baum (1991) in their categorization (note: Christiansen’s and Baum’s most recent hierarchy does not use the word activity at all, possibly because there is a lack of consensus about whether activity is a component of a task or vice versa). Activity was defined as “a singular pursuit in which a person engages as part of his/her daily occupational experience” and was considered to be “the basic unit of a task” (p. 16). They gave the example of the act of handwriting. Task was defined as “a set of purposeful activities in which a person engages” and could be represented by “the obligation to write a report” (p. 16). Occupation, then, was considered as “groups of self-directed, functional tasks and activities in which a person engages over the lifespan” (p. 16). To continue with the same example, Law et al. suggested that occupation would be “a managerial position requiring an individual to engage in frequent report writing” (p. 16), which might constitute one of their professional activities.

Law et al. (1996) further defined “occupations” (the plural) as “those clusters of activities and tasks in which the person engages in order to meet his/her intrinsic needs for self-maintenance, expression and fulfilment” (p. 16) and explained that they are linked to roles and conducted in the context of multiple environments. This definition emphasizes that self-maintenance, expression and fulfilment are understood as intrinsic needs and that people engage in occupations within the context of their specific roles and environments. It is these roles and environments that shape the process and purpose of occupations for a particular person.

Occupational performance results from the interconnectedness of the person, what he/she is aiming to do and where it will be done. However, the rich connections between these three factors are evident when realizing that even individuals’ decisions about what to do are shaped by the broader context in which they live their lives. Occupational performance is the result of a complex process in which people determine the purpose of occupations in their lives; a process that is shaped by their perceptions, goals, responsibilities and desires and the demands of the context in which they live. In a reciprocal way, how they think about themselves and the things people do also influence their environments. Occupational performance also changes over time, as represented in Figure 4.3, as the relationship between person, environment and occupation changes through the lifespan and will differ at different times for any particular person.

FIG 4.3 Person-Environment-Occupation lifespan diagram.

From Law M., Cooper B., Strong S., Stewart D., Rigby P., Letts L., The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance, 1996, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 9–23. Reprinted with the permission of CAOT Publications ACE.

Central to the model is the concept of the person-environment-occupation fit. The degree of congruence between these three elements affects occupational performance. As Law et al. (1996) stated, “the outcome of greater compatibility is therefore represented as more optimal occupational performance” (p. 17). When the congruence between them diminishes, occupational performance is impeded. In Figure 4.3, three circles overlapped to different extents represents this process. As evident in the diagram, these overlapping circles come from a cross-section of the diagram used to represent the temporal aspects of occupational performance throughout the lifespan. The effect of greater or lesser congruence between person, environment and occupation on occupational performance is apparent. The goal of occupational therapy is to improve occupational performance (if it is reduced) by facilitating or enhancing the fit between person, environment and occupation.

Written at a time when a systems approach and the biopsychosocial model of health were prominent ideas, the PEO particularly emphasized that occupational performance was person-, environment- and occupation-specific and that the three could not be considered separately. Consequently, intervention could be targeted at any one or more of the three elements, as a change in one would be expected to lead to a change in the others. However, it is important to note that a transactive understanding of the relationship among the three components means that, while a change is expected, the exact nature of that change cannot be predicted.

At the time, Law et al. (1996) listed four advantages of using the PEO Model of Occupational Performance. These were that:

Historical description of model’s development

There is a certain level of symmetry in placing a transactional model, which assumes that action takes place within a particular context, within its particular historical and geographical context. This model was published in 1996, a decade in which occupational therapy models were commonly emphasizing occupational therapy’s assumption that people should be understood in a holistic way. That is, they should be understood as both ‘whole’ people (rather than just bodies) and people who live in a particular context (their ‘whole’ situation). Placed within the broader context of models of health, it was a time when a biopsychosocial understanding of health was becoming more established, in contrast to the biomedical understanding characteristic of the preceding period.

Law et al. (1996) claimed that the importance of the relationship between person and environment had been well recognized during the profession’s early history but not emphasized from the 1940s to the 1960s (a time Reed, 2005, described as the mechanistic period and characterized by the ‘forgetting’ of many formative concepts). Law et al. summed up this view of the situation by saying, “Occupational performance results from the dynamic relationship between people, their occupations and roles, and the environments in which they live, work and play. There have, however, been few models of practice in the occupational therapy literature which discuss the theoretical and clinical applications of person-environment interaction” (p. 9). Presumably, the authors saw the need for occupational therapy to make explicit its contextualized understanding of human occupation.

The main publication presenting this model appeared in the Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy in 1996. In providing their rationale for the model, Law et al. (1996) argued that occupational therapy’s “views on the relationship between occupation and the environment have altered” (p. 10), in that they had moved away from the cause and effect assumptions inherent within a biomedical model of health and moved towards a more “transactive” (p. 10) understanding of occupational performance. They also provided a literature review, highlighting key publications that demonstrated “the importance of the environment in influencing behaviour and the use of the environment as a treatment modality in occupational therapy” (p. 13). They noted that this concern had been increasingly discussed from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. Thus, they placed the model within the existing trends in occupational therapy.

This placing of the model within existing trends might suggest that the authors were aiming to describe the theory and practice of occupational therapy at the time, rather than intending to shape it into a new understanding. (This is different from some of the other models reviewed in this book, which do appear to have the aim of shaping occupational therapy theory and practice in particular ways.) If this assumption is correct, it might help to explain why this model is so well known and used, despite having only been published in one major article. That is, it may have provided occupational therapists with a language and concepts for describing what they believed about their theory and practice related to occupation. Certainly, the concepts of person, environment and occupation being interdependent and mutually influencing have become central to occupational therapy discourse about human action in the intervening years.

Law et al. (1996) also explained that “the previous medical orientation of practice has linked occupational therapy more naturally with other health professionals and not necessarily fostered interaction with social scientists, human geographers, architects and interior designers, interested in planning therapeutic and enabling environments” (p. 14). This is an interesting statement to reflect upon more than two decades later, when we have seen similar sentiments expressed by those advocating for an occupational science approach and we also see the healthcare context having changed to incorporate a broader view of health and the proliferation of occupational therapists working in areas other than health.

Summary

The PEO model presents the three major components of occupational therapy’s domain of concern (person, environment and occupation) and conceptualizes their relationship as transactive. This means that they should not be considered separately but are considered mutually influencing, in that a change in any one or more domains leads to a change in the others. While such change is expected, the model suggests that the exact nature of the change cannot be predicted or controlled (a change will definitely occur but a particular type of change cannot be predetermined). The degree to which these three components fit together influences occupational performance. That is, if the congruence among person-environment-occupation is high, then occupational performance will be enhanced. If the fit is poor, occupational performance is reduced. The aim of occupational therapy is to facilitate occupational performance by intervening in any one or more of these areas to enhance the congruence between person, environment and occupation.

Memory aid

See Box 4.2.

BOX 4.2 Person-Environment-Occupation Model of Occupational Performance (PEO) memory aid

Ecology of Human Performance

Ecology of Human Performance (EHP) is the second model that conceptualizes the environment as an inseparable aspect of occupation. That is, it is the context within which people act and which shapes and is shaped by that action. As the name suggests, the model is informed by the principles of ecology. It was developed at a similar time to the PEO and published 2 years earlier.

Main concepts and definitions of terms

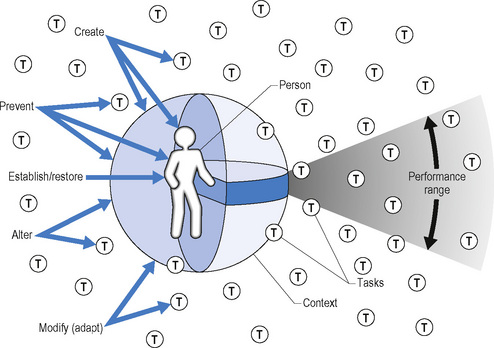

EHP emphasizes the environment as the primary context within which performance needs to be understood. It is a lens through which all human performance should be viewed. The term ecology refers to the “interrelationships of organisms and their environments” (Dunn et al., 1994, p. 595) and the model emphasizes the inter relatedness of person, context, task and performance. The model was first published in 1994. In the original publication, the authors stated, “the primary theoretical postulate fundamental to the EHP framework is that ecology, or the interaction between person and the environment, affects human behaviour and performance, and that performance cannot be understood outside of context” (p. 598). Thus, context is central to human performance. Figure 4.4 provides a diagrammatic representation of EHP. In this model (Dunn, 2007) there are three important constructs − person, task and context (initially called environment) − which contribute to an understanding of the fourth construct: human performance.

FIG 4.4 Ecology of Human Performance. http://lww.com

Reprinted from Dunn in Kramer (1994), Perspectives in Human Occupation, with permission from Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins.

A central feature of this model is the primary importance to human performance of environment or context. The model conceptualizes the environment as the broader context that is integral to and shapes both the person and his or her task performance (not limited to the physical context in which a task is performed). This understanding of the environment has two aspects that need to be considered in more depth. These are: (a) that the environment includes more than just the physical environment; and (b) that the environment has the capacity to shape task performance.

First, while the earlier publications of the model use the term environment (or context-environment), the authors articulated very clearly that the term is conceptualized very broadly and should not be limited to the physical environment. They stated that the concept of the environment should be expanded to include, “physical, temporal, social, and cultural elements” (Dunn et al., 1994, p. 596). By expanding the definition of environment in this way, Dunn et al. emphasized the contribution that occupational therapists can make to an understanding of the interdependent relationship between the person and environment. They claimed that a broad definition of environment helps to make explicit the complexity of the person–environment relationship to a level that is beyond the scope of the work done by environmental psychologists (who mainly focused on the physical environment). In particular, a broader concept of the environment allows occupational therapists to consider the meaning of the physical, temporal, social and cultural environment to the person.

Second, while the influence of the environment on human performance has long been acknowledged in occupational therapy, the EHP model emphasizes that the environment also shapes both the person and the tasks in which the person engages. In a review of the social science literature on the effect of the environment, Dunn et al. (1994, p. 596) cited a range of different authors and the main emphasis of their work. These included:

These are just a few of the ideas that influenced the EHP’s concept of the importance of the environment in shaping how people view themselves and what they do.

As the focus of the model is the relationship between person and environment, the second construct that we will discuss here is person. Dunn et al (2003) stated that “the Ecology of Human Performance is an individually focused, client-centred framework. Individuals are seen as unique and complex” (p. 225). Personal variables contribute to the uniqueness of individuals. These are listed in the model as values, interests and experiences, as well as sensori-motor, cognitive and psychosocial skills. These personal variables influence both the selection of tasks and the quality of task performance. These personal variables are also continually influenced by the person’s (continually changing) context.

The third construct is task. The model takes the view that a multitude of tasks are potentially available to all people. These are represented in Figure 4.4 by the capital Ts that lie outside of the person-context sphere. However, personal and environmental variables influence the tasks that form part of an individual’s actual repertoire of tasks. Personal variables such as interests, values, perceptions and experience as well as sensorimotor, cognitive and psychosocial skills and abilities influence the selection of tasks in which the person participates. Environmental variables also influence task selection and performance. For example, some tasks might not be easily accessed in certain environments such as snow skiing in a temperate climate while others might not be socially or culturally valued. In addition, a person might engage in a selection of tasks because the context ‘requires’ these tasks of them. Examples include those tasks that are required in order to fulfil the particular social roles expected of the person. The set of tasks in which a particular person engages will depend on the unique relationship between the person and his or her specific context. This set of tasks is referred to as the performance range and people select from the available range of tasks. The performance range is influenced by a person’s skills and abilities and the supports and barriers created by the particular context. As people and contexts change, so too do their performance ranges.

The final construct in the model is human performance. This is the result of the interaction between person, context and task.

Interventions

In addition to the four core constructs already discussed, EHP also addresses five categories of interventions. These are establish/restore, alter, adapt, prevent and create. These five alternatives for intervention relate variously to person, context and task.

First, therapeutic interventions can aim to establish or restore an individual’s skills and abilities. This intervention refers to either establishing skills that people haven’t had previously or restoring skills and abilities that have been lost, usually through acquiring a medical condition, injury or disability. Dunn et al. (1994) made the point that restorative interventions are very common among occupational therapists working within a biomedical model, with its corrective emphasis. While these interventions target the individual’s skills and abilities, Dunn et al. stressed that context can be important in these types of intervention and gave the example of the importance of predictable environments in the provision of feedback for correcting motor behaviours.

The second way that occupational therapists might intervene is to alter or change the actual environment, that is, to select a different environment in which the person is able to perform the task. This intervention aims to create the best match between the person and his or her environment and focuses on selecting a different environment rather than adapting the current environment (i.e. not to be confused with altering or making changes to the current environment).

The third intervention alternative is to adapt the contextual features and/or task demands. Regarding contextual features, these could be enhanced or minimized to match better the person’s abilities. Similarly, aspects of the task such as the sequence of steps, the tools used, the position required of the person and the skills required of the person can be adapted to enable the person to participate in the task.

The fourth intervention alternative is to prevent. In this option, occupational therapists might aim to “prevent the occurrence or evolution of maladaptive performance in context” (Dunn et al., 1994, p. 604). This intervention strategy aims to prevent difficulties arising. To do this, occupational therapists might address person, context and/or task.

The final intervention option is called create and was described by Dunn et al. as “creating circumstances that promote more adaptable or complex performance in context” (p. 604). The authors stressed that this intervention does not assume the presence of a disability or that there is a problem that will interfere with performance.

Historical description of model’s development

Like PEO, EHP was developed at a time when the profession was making more explicit its fundamental assumptions about the importance of the environment in occupational performance. In many ways, the 1990s could be seen as a time in occupational therapy’s history where the reductionism of the mechanistic period was increasingly being critiqued and many of occupational therapy’s fundamental beliefs were being reaffirmed.

The EHP model was developed by the Department of Occupational Therapy at the University of Kansas, originally for three reasons outlined by Dunn (2007). These were:

According to Dunn, the EHP model was successful in supporting all three original aims. At the time that the model was developed, the authors (Dunn et al., 1994) explained that, while the environment had been “a recurring theme in the occupational therapy literature” (p. 595), insufficient attention had been made to the influence of contextual features on human performance. Dunn (2007) also emphasized that, at the time, the context had also been neglected by other services as well as occupational therapy.

In the three major publications on this model between 1994 and 2007, the model has undergone very little change. The major difference is really one of categorization, in that, the original version of the model included “therapeutic intervention” as a fifth construct in the practice of occupational therapy (in addition to person, task, context and occupational performance). While intervention was not listed as a separate construct in later versions of the model, the five different intervention strategies outlined in the earlier version (establish/restore, alter, adapt, prevent and create) have remained an integral part of the model.

In discussing the development of the model, Dunn (2007) emphasized the conscious decision not to use the term “occupation” in the EHP model. This was because one of its original purposes was to provide a framework from which to work with colleagues outside the discipline of occupational therapy and the authors thought the particular way that occupational therapists use the term occupation could make this process difficult. Instead, the term “task” was used, as the developers were of the opinion it had utility and a common understanding within everyday language. However, in the later publications, the concept of occupation, which had very much taken root in occupational therapy discourse by then, was discussed more overtly. For example, in explaining the choice to use the word task in a 2007 publication, Dunn emphasized that the “construct of occupation” (p. 128), whereby a person derives meaning from performance of a task in context, is important to understanding human performance.

While EHP has gone through little change or development over time, it has had a broad influence on occupational therapy. In 2007, Dunn stated, “One of the most helpful benefits of including context is that intervention options expand” (p. 128). Interestingly, the five intervention approaches that they identified in 1994 – establish/restore, adapt/modify, alter, prevent and create – appear to have influenced the American Occupational Therapy Association’s Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (AOTA, 2002, 2008), as these five appear unchanged in that document as treatment planning and implementation strategies.

Summary

EHP is an ecological model of occupational therapy that emphasizes the context through which task performance should be viewed. Whereas other models of practice in occupational therapy generally start with the person and focus on occupational performance in context, this model starts with context. Using the image of the window presented in the Introduction, it is as if context is the window through which the model looks at occupational performance. In contrast, the window in most other occupational therapy models is generally occupation, with the variation between models relating to whether they include the window in the description of what is seen or not.

The model was first published in 1994 and has changed very little in the three major publications in which it has been presented. The primary focus of the model is the person in context. This person in context has a range of tasks available to them and this range is influenced by both person and context. The role of occupational therapy is to identify this performance range of available tasks and determine whether it meets the needs of the person in that context. The model outlines five intervention options:

Memory aid

See Box 4.3.

BOX 4.3 Ecology of Human Performance memory aid

In this situation:

Intervention planning

Establish/restore Establish/restore |

Personal skills & abilities |

Alter (different environment) Alter (different environment) |

Context (environmental variables) |

Adapt/modify Adapt/modify |

Context (environmental variables) |

| Task (demands of) | |

| Context (environmental variables) | |

Prevent (anticipate problem) Prevent (anticipate problem) |

Personal variables |

| Task variables | |

| Context (environmental variables) | |

Create Create |

Personal variables |

| Task variables | |

| Context (environmental variables) |

Dunn W. Ecology of Human Performance Model. In: Dunbar S.B., editor. Occupational therapy models for intervention with children and families. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2007:127-155.

Dunn W., Brown C., McQuigan A. The ecology of human performance: A framework for considering the effect of context. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1994;48(7):595-607.

Dunn W., Brown C., Youngstrom M.J. Ecological model of occupation. In: Kramer P., Hinojosa J., Royeen C.B., editors. Perspectives in human occupation: participation in life. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:222-263.

Conclusion

In this chapter we reviewed three models of practice that are often referred to as ecological because of the particular emphasis they place on the environment. The PEOP model was presented first as it could be considered to provide a bridge between the occupational performance models and the more deeply ecological models. The PEOP is unique in that it provides substantial detail about the capacities of the individual that affect performance while also providing substantial detail about the environmental context. Both person and environment are presented as two equally important and mutually influencing factors upon which people perform occupation for the purpose of occupational performance and participation in society.

The PEO model has become widely known and there has been broad acceptance of the importance of person, environment and occupation in occupational therapy theory and practice more generally. The idea that person, environment and occupation are tied together in a transactive relationship is central to the model, the implication being that they cannot be considered separately. Ecology of Human Performance also presents the environment as something through which occupational performance must be understood.

These ecological approaches to occupational therapy have been important influences in shaping the profession’s understanding of occupation. The importance of the environment as central to occupation and its performance has become well accepted in the broader occupational therapy discourse. In Chapter 5, the CMOP-E is presented. This model introduces another important concept that may shape occupational therapy thinking in the future. That is the importance of a just society.

American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 2002;56:609-639.

American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 2008;62:625-683.

Baum C., Christiansen C. Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance: An occupation-based framework for practice. In: Christiansen C.H., Baum C.M., Bass-Haugen J., editors. Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being. third ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2005:243-259.

Brown C.E. Ecological models in occupational therapy. In: Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Boyt Schell B.A., editors. Willard & Spackman’s occupational therapy. eleventh ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:435-445.

Bruner J. Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Christiansen C. Occupational therapy: Intervention for life performance. In: Christiansen C., Baum C., editors. Occupational therapy: Overcoming human performance deficits. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1991:3-43.

Christiansen C., Baum C. Occupational therapy: Overcoming human performance deficits. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 1991.

Christiansen C., Baum C. Person-Environment-Occupational Performance: A conceptual model for practice. In: Christiansen C., Baum C., editors. Occupational therapy: Enabling function and well-being. second ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1997:47-70.

Christiansen C., Baum C. Understanding occupation: Definitions and concepts. In: Christiansen C., Baum C., editors. Occupational therapy: Enabling function and well-being. second ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1997:3-25.

Christiansen C., Baum C. The complexity of occupation. In: Christiansen C.H., Baum C.M., Bass-Haugen J., editors. Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2005:3-17.

Christiansen C.H., Baum C.M., Bass-Haugen J., editors. Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being, third ed, Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 2005.

Dunn W. Ecology of Human Performance Model. In: Dunbar S.B., editor. Occupational therapy models for intervention with children and families. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2007:127-155.

Dunn W., Brown C., McGuigan A. The ecology of human performance: A framework for considering the effect of context. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1994;48(7):595-607.

Dunn W., Brown C., Youngstrom M.J. Ecological model of occupation. In: Kramer P., Hinojosa J., Royeen C.B., editors. Perspectives in human occupation: participation in life. Baltimore, MA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:222-263.

Gibson J.J. An ecological approach to visual perception. Hilldale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1986.

Law M., Cooper B., Strong S., Stewart D., Rigby P., Letts L. The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Can. J. Occup. Ther.. 1996;63(1):9-23.

Lawton M.P. Competence, environmental press, and the adaption of older people. In: Lawton M.P., Windley P.G., Byerts T.O., editors. Aging and the environment. New York: Springer; 1982:33-59.

Murray H.A. Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford, 1938.

Nelson D. Occupation: Form and performance. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1988;42:633-641.

Reed K. An annotated history of the concepts used in occupational therapy. In: Christiansen C.H., Baum C.M., Bass-Haugen J., editors. Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being. third ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2005:567-626.